| Family II. FALCONINAE.

FALCONINE BIRDS. GENUS IV. HALIAETUS, Savigny. SEA-EAGLE. |

Next >> |

Family |

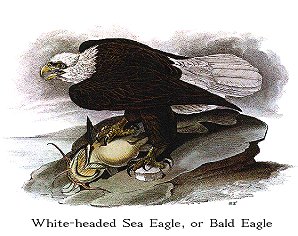

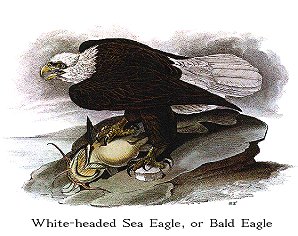

WHITE-HEADED OR BALD EAGLE. [Bald Eagle (see also Washington Sea-Eagle).] |

| Genus | HALIAETUS LEUCOCEPHALUS, Linn. [Haliaeetus leucocephalus.] |

The figure of this noble bird is well known throughout the civilized world,

emblazoned as it is on our national standard, which waves in the breeze of every

clime, bearing to distant lands the remembrance of a great people living in a

state of peaceful freedom. May that peaceful freedom last for ever!

The great strength, daring, and cool courage of the White-headed Eagle,

joined to his unequalled power of flight, render him highly conspicuous among

his brethren. To these qualities did he add a generous disposition towards

others, he might be looked up to as a model of nobility. The ferocious,

overbearing, and tyrannical temper which is ever and anon displaying itself in

his actions, is, nevertheless, best adapted to his state, and was wisely given

him by the Creator to enable him to perform the office assigned to him.

The flight of the White-headed Eagle is strong, generally uniform, and

protracted to any distance, at pleasure. Whilst travelling, it is entirely

supported by equal easy flappings, without any intermission, in as far as I have

observed it, by following it with the eye or the assistance of a glass. When

looking for prey, it sails with extended wings, at right angles to its body, now

and then allowing its legs to hang at their full length. Whilst sailing, it has

the power of ascending in circular sweeps, without a single flap of the wings,

or any apparent motion either of them or of the tail; and in this manner it

often rises until it disappears from the view, the white tail remaining longer

visible than the rest of the body. At other times, it rises only a few hundred

feet in the air, and sails off in a direct line, and with rapidity. Again, when

thus elevated, it partially closes its wings, and glides downwards for a

considerable space, when, as if disappointed, it suddenly checks its career, and

resumes its former steady flight. When at an immense height, and as if

observing an object on the ground, it closes its wings, and glides through the

air with such rapidity as to cause a loud rustling sound, not unlike that

produced by a violent gust of wind passing amongst the branches of trees. Its

fall towards the earth can scarcely be followed by the eye on such occasions,

the more particularly that these falls or glidings through the air usually take

place when they are least expected.

At times, when these Eagles, sailing in search of prey, discover a Goose, a

Duck, or a Swan, that has alighted on the water, they accomplish its destruction

in a manner that is worthy of your attention. The Eagles, well aware that

water-fowl have it in their power to dive at their approach, and thereby elude

their attempts upon them, ascend in the air in opposite directions over the lake

or river, on which they have observed the object which they are desirous of

possessing. Both Eagles reach a certain height, immediately after which one of

them glides with great swiftness towards the prey; the latter, meantime, aware

of the Eagle's intention, dives the moment before he reaches the spot. The

pursuer then rises in the air, and is met by its mate, which glides toward the

water-bird, that has just emerged to breathe, and forces it to plunge again

beneath the surface, to escape the talons of this second assailant. The first

Eagle is now poising itself in the place where its mate formerly was, and rushes

anew to force the quarry to make another plunge. By thus alternately gliding,

in rapid and often repeated rushes, over the ill-fated bird, they soon fatigue

it, when it stretches out its neck, swims deeply, and makes for the shore, in

the hope of concealing itself among the rank weeds. But this is of no avail,

for the Eagles follow it in all its motions, and the moment it approaches the

margin, one of them darts upon it, and kills it in an instant, after which they

divide the spoil.

During spring and summer, the White-headed Eagle, to procure sustenance,

follows a different course, and one much less suited to a bird apparently so

well able to supply itself without interfering with other plunderers. No sooner

does the Fish-Hawk make its appearance along our Atlantic shores, or ascend our

numerous and large rivers, than the Eagle follows it, and, like a selfish

oppressor, robs it of the hard-earned fruits of its labour. Perched on some

tall summit, in view of the ocean, or of some water-course, he watches every

motion of the Osprey while on wing. When the latter rises from the water, with

a fish in its grasp, forth rushes the Eagle in pursuit. He mounts above the

Fish-Hawk, and threatens it by actions well understood, when the latter, fearing

perhaps that its life is in danger, drops its prey. In an instant, the Eagle,

accurately estimating the rapid descent of the fish, closes his wings, follows

it with the swiftness of thought, and the next moment grasps it. The prize is

carried off in silence to the woods, and assists in feeding the ever-hungry

brood of the marauder.

This bird now and then procures fish himself, by pursuing them in the

shallows of small creeks. I have witnessed several instances of this in the

Perkiomen Creek in Pennsylvania, where in this manner, I saw one of them secure

a number of Red-fins, by wading briskly through the water, and striking at them

with his bill. I have also observed a pair scrambling over the ice of a frozen

pond, to get at some fish below, but without success.

It does not confine itself to these kinds of food, but greedily devours

young pigs, lambs, fawns, poultry, and the putrid flesh of carcasses of every

description, driving off the Vultures and Carrion Crows, or the dogs, and

keeping a whole party at defiance until it is satiated. It frequently gives

chase to the Vultures, and forces them to disgorge the contents of their

stomachs, when it alights and devours the filthy mass. A ludicrous instance of

this took place near the city of Natchez, on the Mississippi. Many Vultures

were engaged in devouring the body and entrails of a dead horse, when a

White-headed Eagle accidentally passing by, the Vultures all took to wing, one

among the rest with a portion of the entrails partly swallowed, and the

remaining part, about a yard in length, dangling in the air. The Eagle

instantly marked him, and gave chase. The poor Vulture tried in vain to

disgorge, when the Eagle, coming up, seized the loose end of the gut, and

dragged the bird along for twenty or thirty yards, much against its will, until

both fell to the ground, when the Eagle struck the Vulture, and in a few moments

killed it, after which he swallowed the delicious morsel.

The Bald Eagle has the power of raising from the surface of the water any

floating object not heavier than itself. In this manner it often robs the

sportsman of ducks which have been killed by him. Its audacity is quite

remarkable. While descending the Upper Mississippi, I observed one of these

Eagles in pursuit of a Green-winged Teal. It came so near our boat, although

several persons were looking on, that I could perceive the glancings of its eye.

The Teal, on the point of being caught, when not more than fifteen or twenty

yards from us, was saved from the grasp of its enemy, one of our party having

brought the latter down by a shot, which broke one of its wings. When taken on

board, it was fastened to the deck of our boat by means of a string, and was fed

by pieces of catfish, some of which it began to eat on the third day of its

confinement. But, as it became a very disagreeable and dangerous associate,

trying on all occasions to strike at some one with its talons, it was killed and

thrown overboard.

When these birds are suddenly and unexpectedly approached or surprised,

they exhibit a great degree of cowardice. They rise at once and fly off very

low, in zig-zag lines, to some distance, uttering a hissing noise, not at all

like their usual disagreeable imitation of a laugh. When not carrying a gun,

one may easily approach them; but the use of that instrument being to appearance

well known to them, they are very cautious in allowing a person having one to

get near them. Notwithstanding all their caution, however, many are shot by

approaching them under cover of a tree, on horseback, or in a boat. They do not

possess the power of smelling gunpowder, as the Crow and the Raven are absurdly

supposed to do; nor are they aware of the effects of spring-traps, as I have

seen some of them caught by these instruments. Their sight, although probably

as perfect as that of any bird, is much affected during a fall of snow, at which

time they may be approached without difficulty.

The White-headed Eagle seldom appears in very mountainous districts, but

prefers the low lands of the sea-shores, those of our large lakes, and the

borders of rivers. It is a constant resident in the United States, in every

part of which it is to be seen. The roosts and breeding places of pigeons are

resorted to by it, for the purpose of picking up the young birds that happen to

fall, or the old ones when wounded. It seldom, however, follows the flocks of

these birds when on their migrations.

When shot at and wounded, it tries to escape by long and quickly repeated

leaps, and, if not closely pursued, soon conceals itself. Should it happen to

fall on the water, it strikes powerfully with expanded wings, and in this manner

often reaches the shore, when it is not more than twenty or thirty yards

distant. It is capable of supporting life without food for a long period. I

have heard of some, which, in a state of confinement, had lived without much

apparent distress for twenty days, although I cannot vouch for the truth of such

statements, which, however, may be quite correct. They defend themselves in the

manner usually followed by other Eagles and Hawks, throwing themselves

backwards, and furiously striking with their talons at any object within reach,

keeping their bill open, and turning their head with quickness to watch the

movements of the enemy, their eyes being apparently more protruded than when

unmolested.

It is supposed that Eagles live to a very great age,--some persons have

ventured to say even a hundred years. On this subject, I can only observe, that

I once found one of these birds, which, on being killed, proved to be a female,

and which, judging by its appearance, must have been very old. Its tail and

wing-feathers were so worn out, and of such a rusty colour, that I imagined the

bird had lost the power of moulting. The legs and feet were covered with large

warts, the claws and bill were much blunted; it could scarcely fly more than a

hundred yards at a time, and this it did with a heaviness and unsteadiness of

motion such as I never witnessed in any other bird of the species. The body was

poor and very tough. The eye was the only part which appeared to have sustained

no injury. It remained sparkling and full of animation, and even after death

seemed to have lost little of its lustre. No wounds were perceivable on its

body.

The White-headed Eagle is seldom seen alone, the mutual attachment which

two individuals form when they first pair seeming to continue until one of them

dies or is destroyed. They hunt for the support of each other, and seldom feed

apart, but usually drive off other birds of the same species. They commence

their amatory intercourse at an earlier period than any other land bird with

which I am acquainted, generally in the month of December. At this time, along

the Mississippi, or by the margin of some lake not far in the interior of the

forest, the male and female birds are observed making a great bustle, flying

about and circling in various ways, uttering a loud cackling noise, alighting on

the dead branches of the tree on which their nest is already preparing, or in

the act of being repaired, and caressing each other. In the beginning of

January incubation commences. I shot a female, on the 17th of that month, as

she sat on her eggs, in which the chicks had made considerable progress.

The nest, which in some instances is of great size, is usually placed on a

very tall tree, destitute of branches to a considerable height, but by no means

always a dead one. It is never seen on rocks. It is composed of sticks, from

three to five feet in length, large pieces of turf, rank weeds, and Spanish moss

in abundance, whenever that substance happens to be near. When finished, it

measures from five to six feet in diameter, and so great is the accumulation of

materials, that it sometimes measures the same in depth, it being occupied for a

great number of years in succession, and receiving some augmentation each

season. When placed in a naked tree, between the forks of the branches, it is

conspicuously seen at a great distance. The eggs, which are from two to four,

more commonly two or three, are of a dull white colour, and equally rounded at

both ends, some of them being occasionally granulated. Incubation lasts for

more than three weeks, but I have not been able to ascertain its precise

duration, as I have observed the female on different occasions sit for a few

days in the nest, before laying the first egg. Of this I assured myself by

climbing to the nest every day in succession, during her temporary absence,--a

rather perilous undertaking when the bird is sitting.

I have seen the young birds when not larger than middle-sized pullets. At

this time they are covered with a soft cottony kind of down, their bill and legs

appearing disproportionately large. Their first plumage is of a greyish colour,

mixed with brown of different depths of tint, and before the parents drive them

off from the nest they are fully fledged. As a figure of the Young White-headed

Eagle will appear in the course of the publication of my Illustrations, I shall

not here trouble you with a description of its appearance. I once caught three

young Eagles of this species, when fully fledged, by having the tree, on which

their nest was, cut down. It caused great trouble to secure them, as they could

fly and scramble much faster than any of our party could run. They, however,

gradually became fatigued, and at length were so exhausted as to offer no

resistance, when we were securing them with cords. This happened on the border

of Lake Ponchartrain, in the month of April. The parents did not think fit to

come within gun-shot of the tree while the axe was at work.

The attachment of the parents to the young is very great, when the latter

are yet of a small size; and to ascend to the nest at this time would be

dangerous. But as the young advance, and, after being able to take wing and

provide for themselves, are not disposed to fly off, the old birds turn them

out, and beat them away from them. They return to the nest, however, to roost,

or sleep on the branches immediately near it, for several weeks after. They are

fed most abundantly while under the care of the parents, which procure for them

ample supplies of fish, either accidentally cast ashore, or taken from the Fish

Hawk, together with rabbits, squirrels, young lambs, pigs, opossums, or racoons.

Every thing that comes in the way is relished by the young family, as by the old

birds.

The young birds begin to breed the following spring, not always in pairs of

the same age, as I have several times observed one of these birds in brown

plumage mated with a full-coloured bird, which had the head and tail pure white.

I once shot a pair of this kind, when the brown bird (the young one) proved to

be the female.

This species requires at least four years before it attains the full beauty

of its plumage when kept in confinement. I have known two instances in which

the white of the head did not make its appearance until the sixth spring. It is

impossible for me to say how much sooner this state of perfection is attained,

when the bird is at full liberty, although I should suppose it to be at least

one year, as the bird is capable of breeding the first spring after birth.

The weight of Eagles of this species varies considerably. In the males, it

is from six to eight pounds, and in the females from eight to twelve. These

birds are so attached to particular districts, where they have first made their

nest, that they seldom spend a night at any distance from the latter, and often

resort to its immediate neighbourhood. Whilst asleep, they emit a loud hissing

sort of snore, which is heard at the distance of a hundred yards, when the

weather is perfectly calm. Yet, so light is their sleep, that the cracking of a

stick under the foot of a person immediately wakens them. When it is attempted

to smoke them while thus roosted and asleep, they start up and sail off without

uttering any sound, but return next evening to the same spot.

Before steam navigation commenced on our western rivers, these Eagles were

extremely abundant there, particularly in the lower parts of the Ohio, the

Mississippi, and the adjoining streams. I have seen hundreds while going down

from the mouth of the Ohio to New Orleans, when it was not at all difficult to

shoot them. Now, however, their number is considerably diminished, the game on

which they were in the habit of feeding, having been forced to seek refuge from

the persecution of man farther in the wilderness. Many, however, are still

observed on these rivers, particularly along the shores of the Mississippi.

In concluding this account of the White-headed Eagle, suffer me, kind

reader, to say how much I grieve that it should have been selected as the Emblem

of my Country. The opinion of our great Franklin on this subject, as it

perfectly coincides with my own, I shall here present to you. "For my part,"

says he, in one of his letters, "I wish the Bald Eagle had not been chosen as

the representative of our country. He is a bird of bad moral character; he does

not get his living honestly; you may have seen him perched on some dead tree,

where, too lazy to fish for himself, he watches the labour of the Fishing-Hawk;

and when that diligent bird has at length taken a fish, and is bearing it to his

nest for the support of his mate and young ones, the Bald Eagle pursues him, and

takes it from him. With all this injustice, he is never in good case, but, like

those among men who live by sharping and robbing, he is generally poor, and

often very lousy. Besides, he is a rank coward: the little King Bird, not

bigger than a Sparrow, attacks him boldly, and drives him out of the district.

He is, therefore, by no means a proper emblem for the brave and honest

Cincinnati of America, who have driven all the King Birds from our country;

though exactly fit for that order of knights which the French call Chevaliers

d'Industrie."

BALD EAGLE, Falco Haliaetus, Wils. Amer. Orn., vol. iv. p. 89. Adult.

SEA EAGLE, Falco ossifragus, Wils. Amer. Orn.,

vol. vii. p. 16. Young.

FALCO LEUCOCEPHALUS, Bonap. Synops., p. 26.

AQUILA LEUCOCEPHALA, WHITE-HEADED EAGLE,

Swains. & Rich. F. Bor. Amer., vol. ii. p. 15.

WHITE-HEADED or BALD EAGLE, Falco leucocephalus, Nutt. Man.,

vol. i. p. 72.

WHITE-HEADED EAGLE, Falco leucocephalus, Aud. Orn. Biog.,

vol. i. p. 160; vol. ii. p. 160; vol. v. p. 354.

Adult Male.

Bill bluish-black, cere light blue, feet pale greyish-blue, tinged

anteriorly with yellow. General colour of upper parts deep umber-brown, the

tail barred with whitish on the inner webs; the upper part of the head and neck

white, the middle part of the crown dark brown; a broad band of the latter

colour from the bill down the side of the neck; lower parts white, the neck

streaked with light brown; anterior tibial feather tinged with brown. Young

with the feathers of the upper parts broadly tipped with brownish-white, the

lower pure white.

Wings long, second quill longest, first considerably shorter. Tail of

ordinary length, much rounded, extending considerably beyond the tips of the

wings; of twelve, broad, rounded feathers.

Bill, cere, edge of eyebrow, iris, and feet yellow; claws bluish-black.

The general colour of the plumage is deep chocolate, the head, neck, tail,

abdomen, and upper and under tail-coverts white.

Length 34 inches; extent of wings 7 feet; bill along the back 2 3/4 inches,

along the under mandible 2 3/4, in depth 1 5/12; tarsus 3, middle toe 3 1/2.

| Next >> |