| Family XXXII. TETRAONINAE. GROUSE. GENUS I. TETRAO, Linn. GROUSE. |

Next >> |

Family |

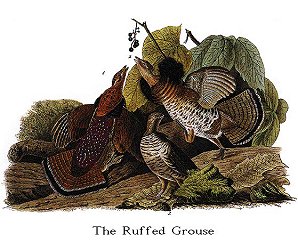

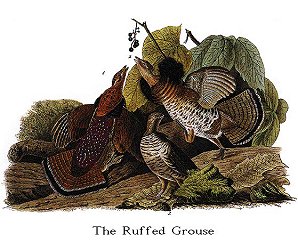

THE RUFFED GROUSE. [Ruffed Grouse.] (State Bird of Pennsylvania) |

| Genus | TETRAO UMBELLUS, Linn. [Bonasa umbellus.] |

You are now presented, kind reader, with a species of Grouse, which, in my

humble opinion, far surpasses as an article of food every other land-bird which

we have in the United States, except the Wild Turkey, when in good condition.

You must not be surprised that I thus express an opinion contradictory to that

of our Eastern epicures, who greatly prefer the flesh of the Pinnated Grouse to

that of the present species, for I have had abundant opportunity of knowing

both. Perhaps, after all, the preference may depend upon a peculiarity in my

own taste; or I may give the superiority to the Ruffed Grouse, because it is as

rarely met with in the Southern States, where I have chiefly resided, as the

Pinnated Grouse is in the Middle Districts; and were the bon-vivants of our

eastern cities to be occasionally satiated with the latter birds, as I have

been, they might possibly think their flesh as dry and flavourless as I do.

The names of Pheasant and Partridge have been given to the present species

by our forefathers, in the different districts where it is found. To the west

of the Alleghanies, and on those mountains, the first name is generally used.

The same appellation is employed in the Middle Districts, to the east of the

mountains, and until you enter the State of Connecticut; after which that of

Partridge prevails.

The Ruffed Grouse, although a constant resident in the districts which it

frequents, performs partial sorties at the approach of autumn. These are not

equal in extent to the peregrinations of the Wild Turkey, our little Partridge,

or the Pinnated Grouse, but are sufficiently so to become observable during the

seasons when certain portions of the mountainous districts which they inhabit

becomes less abundantly supplied with food than others. These partial movings

might not be noticed, were not the birds obliged to fly across rivers of great

breadth, as whilst in the mountain lands their groups are as numerous as those

which attempt these migrations; but on the north-west banks of the Ohio and

Susquehanna rivers, no one who pays the least attention to the manners and

habits of our birds, can fail to observe them. The Grouse approach the banks of

the Ohio in parties of eight or ten, now and then of twelve or fifteen, and, on

arriving there, linger in the woods close by for a week or a fortnight, as if

fearful of encountering the danger to be incurred in crossing the stream. This

usually happens in the beginning of October, when these birds are in the very

best order for the table, and at this period great numbers of them are killed.

If started from the ground, with or without the assistance of a dog, they

immediately alight on the nearest trees, and are easily shot. At length,

however, they resolve upon crossing the river; and this they accomplish with so

much ease, that I never saw any of them drop into the water. Not more than two

or three days elapse after they have reached the opposite shore, when they at

once proceed to the interior of the forests, in search of places congenial to

the general character of their habits. They now resume their ordinary manner of

living, which they continue until the approach of spring, when the males, as if

leading the way, proceed singly towards the country from which they had

retreated. The females follow in small parties of three or four. In the month

of October 1820, I observed a larger number of Ruffed Grouse migrating thus from

the States of Ohio, Illinois and Indiana into Kentucky, than I had ever before

remarked. During the short period of their lingering along the north-west shore

of the Ohio that season, a great number of them were killed, and they were sold

in the Cincinnati market for so small a sum as 12 1/2 cents each.

Although these birds are particularly attached to the craggy sides of

mountains and hills, and the rocky borders of rivers and small streams, thickly

mantled with evergreen trees and small shrubs of the same nature, they at times

remove to low lands, and even enter the thickest cane-brakes, where they also

sometimes breed. I have shot some, and have heard them drumming in such places,

when there were no hills nearer than fifteen or twenty miles. The lower parts

of the State of Indiana and also those of Kentucky, are amongst the places where

I have discovered them in such situations.

The charming groves which here and there contrast so beautifully with the

general dull appearance of those parts of Kentucky and Tennessee, to which the

name of Barrens is given, are sought by the Ruffed Grouse. These groves afford

them abundant food and security. The gentle coolness that prevails in them

during the summer heat is agreeable and beneficial to these birds, and the

closeness of their undergrowth in other spots moderates the cold blasts of

winter. There this species breeds, and is at all times to be found. Their

drumming is to be heard issuing from these peaceful retreats in early spring, at

the same time that the booming of their relative, the Pinnated Grouse, is

recognised, as it reaches the ear of the traveller, from the different parts of

the more open country around. In such places as the groves just mentioned, the

species now before you, kind reader, is to be met with, as you travel towards

the south, through the whole of Tennessee and the Choctaw Territory; but as you

approach the city of Natchez they disappear, nor have I ever heard of one of

these birds having been seen in the State of Louisiana.

The mountainous parts of the Middle States being more usually the chosen

residence of this species, I shall, with your permission, kind reader, return to

them, and try to give you an account of this valuable Grouse.

The flight of the Ruffed Grouse is straight-forward, rather low, unless

when the bird has been disturbed, and seldom protracted beyond a few hundred

yards at a time. It is also stiff, and performed with a continued beating of

the wings for more than half its duration, after which the bird sails and seems

to balance its body as it proceeds through the air, in the manner of a vessel

sailing right before the wind. When this bird rises from the ground at a time

when pursued by an enemy, or tracked by a dog, it produces a loud whirring

sound, resembling that of the whole tribe, excepting the Black Cock of Europe,

which has less of it than any other species. This whirring sound is never heard

when the Grouse rises of its own accord, for the purpose of removing from one

place to another; nor, in similar circumstances, is it commonly produced by our

little Partridge. In fact, I do not believe that it is emitted by any species

of Grouse, unless when surprised and forced to rise. I have often been lying on

the ground in the woods or the fields for hours at a time, for the express

purpose of observing the movements and habits of different birds, and have

frequently seen a Partridge or a Grouse rise on wing from within a few yards of

the spot in which I lay unobserved by them, as gently and softly as any other

bird, and without producing any whirring sound. Nor even when this Grouse

ascends to the top of a tree, does it make any greater noise than other birds of

the same size would do.

I have said this much respecting the flight of Grouse, because it is a

prevalent opinion, both among sportsmen and naturalists, that the whirring sound

produced by birds of that genus, is a necessary effect of their usual mode of

flight. But that this is an error, I have abundantly satisfied myself by

numberless observations.

On the ground, where the Ruffed Grouse spends a large portion of its time,

its motions are peculiarly graceful. It walks with an elevated, firm step,

opening its beautiful tail gently and with a well-marked jet, holding erect its

head, the feathers of which are frequently raised, as are the velvety tufts of

its neck. It poises its body on one foot for several seconds at a time, and

utters a soft cluck, which in itself implies a degree of confidence in the bird

that its tout ensemble is deserving of the notice of any bystander. Should the

bird discover that it is observed, its step immediately changes to a rapid run,

its head is lowered, the tail is more widely spread, and if no convenient

hiding-place is at hand, it immediately takes flight with as much of the

whirring sound as it can produce, as if to prove to the observer, that, when on

wing, it cares as little about him as the deer pretends to do, when, on being

started by the hound, he makes several lofty bounds, and erects his tail to the

breeze. Should the Grouse, however, run into a thicket, or even over a place

where many dried leaves lie on the ground, it suddenly stops, squats, and

remains close until the danger is over, or until it is forced by a dog or the

sportsman himself to rise against its wish.

The shooting of Grouse of this species is precarious, and at times very

difficult, on account of the nature of the places which they usually prefer.

Should, for instance, a covey of these birds be raised from amongst Laurels

(Kalmia latifolia) or the largest species of Bay (Rhododendron maximum), these

shrubs so intercept the view of them, that, unless the sportsman proves quite an

adept in the difficult art of pulling the trigger of his gun at the proper

moment, and quickly, his first chance is lost, and the next is very uncertain.

I say still more uncertain, because at this putting up of the birds, they

generally rise higher over the bushes, flying in a straight course, whereas at

the second start, they often fly among the laurels, and rise above them in a

circuitous manner, when to follow them along the barrel of the gun is

considerably more difficult. Sometimes, when these birds are found on the sides

of a steep hill, the moment they start, they dive towards the foot of the

declivity, take a turn, and fly off in a direction so different from the one

expected, that unless the sportsman is aware of the trick, he may not see them

again that day. The young birds often prove equally difficult to be obtained,

for as they are raised from amongst the closely tangled laurels, they only fly a

few yards, and again drop among them. A smart cur-dog generally proves the best

kind on these occasions; for no sooner does he start a covey of Ruffed Grouse

than his barking alarms the birds as much as the report of a gun, and causes

them to rise and alight on the nearest trees, on which they may be shot at with

great success.

This leads me to remark, that the prevailing notion which exists in almost

every district where these birds are numerous, that on firing at the lowest bird

perched on a tree, the next above will not fly, and that by continuing to shoot

at the lowest in succession, the whole may be killed, is contradicted by my

experience; for on every attempt which I have made to shoot several in this

manner on the same tree, my efforts have proved unsuccessful, unless indeed

during a fall of snow, when I have killed three and sometimes four. The same

cause produces the same effect on different birds. It may happen, however, that

in districts covered with deep snow for several weeks, during severe winters,

these birds, becoming emaciated and weak, may stand a repetition of shots from a

person determined to shoot Grouse even when they are good for nothing; but, kind

reader, this barbarous taste is, I hope, no more yours than it is mine.

During spring, and towards the latter part of autumn, at which time the

Ruffed Grouse is heard drumming from different parts of the woods to which it

resorts, I have shot many a fine cock by imitating the sound of its own wings

striking against the body, which I did by beating a large inflated bullock's

bladder with a stick, keeping up as much as possible the same time as that in

which the bird beats. At the sound produced by the bladder and the stick, the

male Grouse, inflamed with jealousy, has flown directly towards me, when, being

prepared, I have easily shot it. An equally successful stratagem is employed to

decoy the males of our little Partridge by imitating the call-note of the female

during spring and summer; but in no instance, after repeated trials, have I been

able to entice the Pinnated Grouse to come towards me, whilst imitating the

booming sounds of that bird.

Early in spring, these birds are frequently seen feeding on the tender buds

of different trees, and at that season are more easily approached than at any

other. Unfortunately, however, they have not by this time recovered their flesh

sufficiently to render them worthy of the attention of a true sportsman,

although their flavour has already improved. When our mountains are covered

with a profusion of huckleberries and whortleberries, about the beginning of

September, then is the time for shooting this species, and enjoying the

delicious food which it affords.

The Ruffed Grouse, on alighting upon a tree, after being raised from the

ground, perches amongst the thickest parts of the foliage, and, assuming at once

an erect attitude, stands perfectly still, and remains silent until all

appearance of danger has vanished. If discovered when thus perched, it is very

easily shot. On rising from the ground, the bird utters a cackling note

repeated six or seven times, and before taking wing emits a lisping sort of

whistle, which seems as if produced by the young of another bird, and is very

remarkable.

When the ground is covered with snow sufficiently soft to allow this bird

to conceal itself under it, it dives headlong into it with such force as to form

a hole several yards in length, re-appears at that distance, and continues to

elude the pursuit of the sportsman by flight. They are sometimes caught while

beneath the snow. Many of them are taken alive in trap boxes during winter,

although the more common method of catching or rather destroying them is by

setting dead falls with a figure-of-four trigger.

Early in April, the Ruffed Grouse begins to drum immediately after dawn,

and again towards the close of day. As the season advances, the drumming is

repeated more frequently at all hours of the day; and where these birds are

abundant, this curious sound is heard from all parts of the woods in which they

reside. The drumming is performed in the following manner. The male bird,

standing erect on a prostrate decayed trunk, raises the feathers of its body, in

the manner of a Turkey-cock, draws its head towards its tail, erecting the

feathers of the latter at the same time, and raising its ruff around the neck,

suffers its wings to droop, and struts about on the log. A few moments elapse,

when the bird draws the whole of its feathers close to its body, and stretching

itself out, beats its sides with its wings, in the manner of the domestic Cock,

but more loudly, and with such rapidity of motion, after a few of the first

strokes, as to cause a tremor in the air not unlike the rumbling of distant

thunder. This, kind reader, is the "drumming" of the Pheasant. In perfectly

calm weather, it may be heard at the distance of two hundred yards, but might be

supposed to proceed from a much greater distance. The female, which never

drums, flies directly to the place where the male is thus engaged, and, on

approaching him, opens her wings before him, balances her body to the right and

left, and then receives his caresses.

The same trunk is resorted to by the same birds during the season, unless

they are frequently disturbed. These trunks are easily known by the quantity of

excrements and feathers about them. The males have the liberty of promiscuous

concubinage, although not to such an extent as those of the Pinnated Grouse.

They have frequent and severe battles at this season, which, although witnessed

by the females, are never interrupted by them. The drumming sounds of these

birds lead to their destruction, every young sportsman taking the unfair

advantage of approaching them at this season, and shooting them in the act.

About the beginning of May, the female retires to some thicket in a close

part of the woods, where she forms a nest. This is placed by the side of a

prostrate tree, or at the foot of a low bush, on the ground, in a spot where a

heap of dried leaves has been formed by the wind. The nest is composed of dried

leaves and herbaceous plants. The female lays from five to twelve eggs, which

are of a uniform dull yellowish colour, and are proportionate in size to the

bird. The latter never covers them on leaving the nest, and in consequence, the

Raven and the Crow, always on the look out for such dainties, frequently

discover and eat them. When the female is present, however, she generally

defends them with great obstinacy, striking the intruder with her wings and

feet, in the manner of the Common Hen.

The young run about and follow the mother, the moment after they leave the

egg. They are able to fly for a few yards at a time, when only six or seven

days old, and still very small. The mother leads them in search of food, covers

them at night with her wings, and evinces the greatest care and affection

towards them on the least appearance of danger, trying by every art in her power

to draw the attention of her enemies to herself, feigning lameness, tumbling and

rolling about as if severely wounded, and by this means generally succeeding in

saving them. The little ones squat at the least chuck of alarm from the mother,

and lie so close as to suffer one to catch them in the hand, should he chance to

discover them, which, however, it is very difficult to do. The males are then

beginning to associate in small parties, and continue separated from the females

until the approach of winter, when males, females, and young mingle together.

During summer, these birds are fond of dusting themselves, and resort to the

roads for that purpose, as well as to pick up gravel. I have observed this

species copulating towards autumn, but have not been able to account for this

unseasonable procedure, as only one brood is raised in the season.

These birds have various enemies besides man. Different species of Hawks

destroy them, particularly the Red-tailed Hawk and the Cooper's Hawk. The

former watches their motions from the tops of trees, and falls upon them with

the swiftness of thought, whilst the latter seizes upon them as he glides

rapidly through the woods. Pole-cats, weasels, racoons, opossums, and foxes,

are all destructive foes to them. Of these, some are content with sucking their

eggs, while others feed on their flesh.

I have found these birds most numerous in the States of Pennsylvania and

New York. They are brought to the markets in great numbers, during the winter

months, and sell at from 75 cents to a dollar apiece, in the eastern cities. At

Pittsburg I have bought them, some years ago, for 12 1/2 cents the pair. It is

said that when they have fed for several weeks on the leaves of the Kalmia

latifolia, it is dangerous to eat their flesh, and I believe laws have been

passed to prevent their being sold at that season. I have, however, eaten them

at all seasons, and although I have found their crops distended with the leaves

of the Kalmia, have never felt the least inconvenience after eating them, nor

even perceived any difference of taste in their flesh. I suspect it is only

when the birds have been kept a long time undrawn and unplucked, that the flesh

becomes impregnated with the juice of these leaves.

The food of this species consists of seeds and berries of all kinds,

according to the season. It also feeds on the leaves of several species of

evergreens, Although these are only resorted to when other food has become

scarce. They are particularly fond of fox-grapes and winter-grapes, as well as

strawberries and dewberries. To procure the latter, they issue from the groves

of the Kentucky Barrens, and often stray to the distance of a mile. They roost

on trees, amongst the thickest parts of the foliage, sitting at some distance

from each other, and may easily be smoked to death, by using the necessary

precautions.

I cannot conclude this article, kind reader, without observing how

desirable the acquisition of this species might be to the sportsmen of Europe,

and especially to those of England, where I am surprised it has not yet been

introduced. The size of these birds, the beauty of their plumage, the

excellence of their flesh, and their peculiar mode of flying, would render them

valuable, and add greatly to the interest of the already diversified sports of

that country. In England and Scotland there are thousands of situations that

are by nature perfectly suited to their habits, and I have not a doubt that a

few years of attention would be sufficient to render them quite as common as the

Grey Partridge.

It is now ascertained that this species extends over the whole breadth of

the Continent, it being found from our Atlantic districts to those bordering the

Pacific Ocean, Mr. TOWNSEND having observed it on the Missouri and along the

Columbia river, and Mr. DRUMMOND having procured specimens in the valleys of the

Columbia river. According to Dr. RICHARDSON, it reaches northward as far as the

56th parallel, and spends the winter on the banks of the Saskatchewan, where it

is plentiful. It also exists in the Texas. It is more abundant in our western,

middle, and eastern districts than in our southern states. In the maritime

portions of South Carolina it does not exist. In Massachusetts, Maine, New

Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, it is very plentiful; but I saw none in Labrador,

although I was assured that it occurs there, and did not hear of it in

Newfoundland.

RUFFED GROUSE, Tetrao umbellus, Wils. Amer. Orn., vol. vi. p. 46.

TETRAO UMBELLUS, Bonap. Syn., p. 126.

TETRAO UMBELLUS, Ruffed Grouse, Swains. & Rich. F. Bor. Amer., vol. ii. p. 342.

RUFFED GROUSE, Nutt. Man., vol. i. p. 657.

RUFFED GROUSE, Tetrao umbellus, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. i. p. 211;vol. v. p. 560.

Male, 18, 24.

Common from Maryland to Labrador, and in the interior from the mountainous

districts to Canada and the Saskatchewan. Columbia river. Resident.

Adult Male.

Bill short, robust, slightly arched, rather obtuse, the base covered by

feathers; upper mandible with the dorsal outline straight in the feathered part,

convex towards the end, the edges overlapping, the tip declinate; under mandible

somewhat bulging toward the tip, the sides convex. Nostrils concealed among the

feathers. Head and neck small. Body bulky. Feet of ordinary length; tarsus

feathered, excepting at the lower part anteriorly, where it is scutellate,

spurless; toes scutellate above, pectinated on the sides; claws arched,

depressed, obtuse.

Plumage compact, glossy. Feathers of the head narrow and elongated into a

curved tuft. A large space on the neck destitute of feathers, but covered over

by an erectile ruff of elongated feathers, of which the upper are silky,

shining, and curved forwards at the end, which is very broad and rounded. Wings

short, broad, much rounded and curved, the third and fourth quills longest.

Tail long, ample, rounded, of eighteen feathers.

Bill horn-colour, brownish-black towards the tip. Iris hazel. Feet

yellowish-grey. Upper part of the head and hind part of the neck bright

yellowish-red. Back rich chestnut, marked with oblong white spots, margined

with black. Upper wing-coverts similar to the back. Quills brownish-dusky,

their outer webs pale reddish, spotted with dusky. Upper tail-coverts banded

with black. Tail reddish-yellow, barred and minutely mottled with black, and

terminated by a broad band of the latter colour, between two narrow bands of

bluish-white, of which one is terminal. A yellowish-white band from the upper

mandible to the eye, beyond which it is prolonged. Throat and lower part of the

neck light brownish-yellow. Lower ruff feathers of the same colour, barred with

reddish-brown, the upper black, with blue reflections. A tuft of light chestnut

feathers under the wings. The rest of the under parts yellowish-white, with

broad transverse spots of brownish-red; the abdomen yellowish-red; and the under

tail-coverts mottled with brown.

Length 18 inches, extent of wings 2 feet; bill along the ridge 3/4, along

the gap 1 1/2; tarsus 1 7/12, middle toe 1 3/4.

Adult Female.

The plumage of the female is less developed and inferior in beauty. The

feathers of the head and ruff are less elongated, the latter of a duller black.

The tints of the plumage generally are lighter than in the male.

A remarkable difference of plumage is observed in specimens from the

opposite parts of the continent, those from the eastern districts being

invariably much greyer, especially on the tail-feathers, than those procured

along the Ohio, or in Virginia. These constant differences have tempted some

persons to suppose that we have two nearly allied species, instead of one; but

after the closest examination of all their parts, as well as of their habits, I

never could find any thing tending to support this supposition. In some

instances, the eggs of what I conceive a young female, have proved much smaller

than others, and Dr. T. M. BREWER has procured in Massachusetts a laying of them

minutely spotted with dull reddish-brown, on a ground of a light salmon colour.

The eggs usually measure an inch and a half in length, by an inch and

two-twelfths in breadth, and are of a uniform dull yellowish tint.

In this species the palate is flat, with two longitudinal ridges converging

anteriorly; the space between these ridges and the slit covered with small

papillae. The tongue is triangular, flattened, sagittate and papillate at the

base, 9 twelfths long, fleshy and pointed. The width of the mouth is 8

twelfths. The liver is extremely small, its lobes equal, and 1 inch in length.

The heart is also small, 11 twelfths long, 7 twelfths in breadth. The oesophagus, Fig. 1 [a b f], is 7 1/4 inches in length; for three inches, [a b], it has

a width of only 5 twelfths; it then enlarges to form a vast crop, [b c d], 3 1/2

inches in breadth, and 2 1/2 inches in length, that part of it connected with

which is 1 inch 5 twelfths in length; it then contracts to 1/2 inch, [e]; the

proventriculus, [e f], 7 1/2 twelfths in breadth. The stomach, [c d], is a very

powerful muscular gizzard, 1 inch 8 twelfths long, 1 inch 9 twelfths broad; the

inferior muscle very large, 1 twelfth thick; the lateral muscles extremely

developed, the left 6 twelfths, the right 5 twelfths in thickness; the

epithelium thick, tough, yellowish-brown, with two concave surfaces, which are

deeply grooved longitudinally. The proventricular glands are large, 3 twelfths

long, occupying a space of only 7 twelfths of an inch in breadth. The duodenum,

[h i], curves at the distance of 4 inches. The intestine, [h i j k], is 4 feet

1 inch long; the coeca come off at the distance of 6 1/4 inches from the

extremity; one of them 17 1/2, the other 16 1/2 inches long; their width for

three inches 4 twelfths, in the rest of their extent 6 twelfths; they are

narrowed toward the end, and terminate in a blunt nipple-like point; their inner

surface has 7 longitudinal ridges, and they are filled with a pultaceous mass.

The width of the duodenum is 5 1/2 twelfths; that of the greater part of the

rest of the intestine 6 twelfths; the cloaca, [k], is not enlarged.

The trachea is 6 inches long, rather slender, its breadth at the top 3

twelfths, at the lower part 2 1/2 twelfths. The rings are feeble and

unossified, 100 in number. There are no inferior laryngeal muscles. The

bronchi are very short, rather wide, of about 12 half rings. The lateral

muscles are rather large, the sterno-tracheal slips moderate.

| Next >> |