| Family XXXV. CHARADRIINAE. PLOVERS. GENUS III. STREPSILAS, Illiger. TURNSTONE. |

Next >> |

Family |

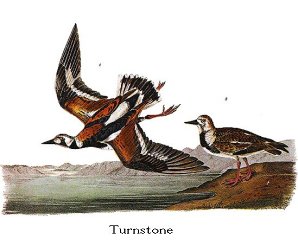

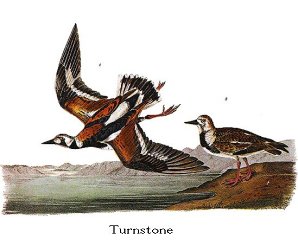

TURNSTONE. [Ruddy Turnstone.] |

| Genus | STREPSILAS INTERPRES, Linn. [Arenaria interpres.] |

This bird, which, in its full vernal dress, is one of the most beautiful of its family, is found along the southern coasts of the United States during

winter, from North Carolina to the mouth of the Sabine river, in considerable

numbers, although perhaps as many travel at that season into Texas and Mexico,

where I observed it on its journey eastward, from the beginning of April to the

end of May, 1837. I procured many specimens in the course of my rambles along

the shores of the Florida Keys, and in the neighbourhood of St. Augustine, and

have met with it in May and June, as well as in September and October, in almost

every part of our maritime shores, from Maine to Maryland. On the coast of

Labrador I looked for it in vain, although Dr. RICHARDSON mentions their arrival

at their breeding quarters on the shores of Hudson's Bay and the Arctic Sea up

to the seventy-fifth parallel.

In spring the Turnstone is rarely met with in flocks exceeding five or six

individuals, but often associates with other species, such as the Knot, the

Red-backed Sandpiper, and the Tringa subarquata. Towards the end of autumn,

however, they collect into large flocks, and so continue during the winter. I

have never seen it on the margins of rivers or lakes, but always on the shores

of the sea, although it prefers those of the extensive inlets so numerous on our

coasts. At times it rambles to considerable distances from the beach, for I

have found it on rocky islands thirty miles from the mainland; and on two

occasions, whilst crossing the Atlantic, I saw several flocks near the Great

Banks flying swiftly, and rather close to the water around the ships, after

which they shot off toward the south-west, and in a few minutes were out of

sight. It seems to be a hardy bird, for some of them remain in our Eastern

Districts until severe frost prevails. Having seen some, in the beginning of

June, and in superb plumage, on the high grounds of the Island of Grand Mannan,

in the Bay of Fundy, I supposed that they bred there, although none of my party

succeeded in discovering their nests. Indeed the young, as I have been

informed, are obtained there, and along the coast of Maine, in the latter part

of July.

I have found this bird much more shy when in company with other species

than when in flocks by itself, when it appears to suspect no danger from man.

Many instances of this seeming inattention have occurred to me, among others the

following:--When I was on the island of Galveston in Texas, my friend EDWARD

HARRIS, My son, and some others of our party, had shot four deer, which the

sailors had brought to our little camp near the shore. Feeling myself rather

fatigued, I did not return to the bushes with the rest, who went in search of

more venison for our numerous crew, but proposed, with the assistance of one of

the sailors, to skin the deer. After each animal was stripped of its hide, and

deprived of its head and feet, which were thrown away, the sailor and I took it

to the water and washed it. To my surprise, I observed four Turnstones directly

in our way to the water. They merely ran to a little distance out of our

course, and on our returning, came back immediately to the same place; this they

did four different times, and, after we were done, they remained busily engaged

in searching for food. None of them were more than fifteen or twenty yards

distant, and I was delighted to see the ingenuity with which they turned over

the oyster-shells, clods of mud, and other small bodies left exposed by the

retiring tide. Whenever the object was not too large, the bird bent its legs to

half their length, placed its bill beneath it, and with a sudden quick jerk of

the head pushed it off, when it quickly picked up the food which was thus

exposed to view, and walked deliberately to the next shell to perform the same

operation. In several instances, when the clusters of oyster-shells or clods of

mud were too heavy to be removed in the ordinary way, they would use not only

the bill and head, but also the breast, pushing the object with all their

strength, and reminding me of the labour which I have undergone in turning over

a large turtle. Among the sea-weeds that had been cast on the shore, they used

only the bill, tossing the garbage from side to side, with a dexterity extremely

pleasant to behold. In this manner, I saw these four Turnstones examine almost

every part of the shore along a space of from thirty to forty yards; after which

I drove them away, that our hunters might not kill them on their return.

On another occasion, when in company with Mr. HARRIS, on the same island I

witnessed a similar proceeding, several Turnstones being engaged in searching

for food in precisely the same manner. At other times, and especially when in

the neighbourhood of St. Augustine, in East Florida, I used to amuse myself with

watching these birds on the racoon-oyster banks, using my glass for the purpose.

I observed that they would search for such oysters as had been killed by the

heat of the sun, and pick out their flesh precisely in the manner of our Common

Oyster-catcher, Haematopus palliatus, while they would strike at such small

bivalves as had thin shells, and break them, as I afterwards ascertained by

walking to the spot. While on the Florida coast, near Cape Sable, I shot one in

the month of May, that had its stomach filled with those beautiful shells, which

on account of their resemblance to grains of rice, are commonly named

rice-shells.

While this species remains in the United States, although its residence is

protracted to many months, very few individuals are met with in as complete

plumage as the one represented in my plate with the wings fully extended; for

out of a vast number of specimens procured from the beginning of March to the

end of May, or from August to May, I have scarcely found two to correspond

precisely in their markings. For this reason, no doubt exists in my mind that

this species, as well as the Knot and several others, loses its rich summer

plumage soon after the breeding season, when the oldest become scarcely

distinguishable from the young. In the spring months, however, I have observed

that they gradually improve in beauty, and acquire full-coloured feathers in

patches on the upper and lower surfaces of the body, in the same manner as the

Knot, the Red-breasted Snipe, the Godwits, and several other species. According

to Mr. HEWITSON, the eggs are four in number, rather suddenly pointed towards

the smaller end, generally an inch and four and a half eighths in length, an

inch and one and a half eighths in their greatest breadth, their ground-colour

pale yellowish-green, marked with irregular patches and streaks of brownish-red,

and a few lines of black.

My drawing of the Turnstones represented in the plate was made at

Philadelphia, in the end of May 1824; and the beautiful specimen exhibited in

the act of flying, I procured near Camden, while in the agreeable company of my

talented friend LESUEUR who, alas! is now no more.

I have not observed any remarkable difference in the plumage of the sexes

at any season of the year. The males I have generally found to be somewhat

larger than the females, which, as is well known, is not the case in the Tringa

family.

My worthy friend, Dr. BACHMAN, once had a bird of this species alive. It

had recovered from a slight wound in the wing, when he presented it to a lady, a

friend of his and mine, who fed it on boiled rice, and bread soaked in milk, of

both of which it was very fond. It continued in a state of captivity upwards of

a year, but was at last killed by accident. It had become perfectly gentle,

would eat from the hand of its kind mistress, frequently bathed in a basin

placed near it for the purpose, and never attempted to escape, although left

quite at liberty to do so.

TURNSTONE, Tringa Interpres, Wile. Amer. Orn., vol. vii. p. 32.

STREPSILAS INTERPRES, Bonap. Syn., p. 299.

STREPSILAS INTERPRES, Turnstone, Swains. and Rich. F. Bor. Amer., Vol. ii.p. 371.

TURNSTONE or SEA DOTTEREL, Nutt. Man., vol. ii. p. 30.

TURNSTONE, Strepsilas Interpres, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. iv. p. 31.

Male, 9, 18 3/4.

Not uncommon along the shores of the Southern States during winter, though

the greater number remove much farther south. Breeds in high northern

latitudes, Hudson's Bay, and shores of Arctic Seas. Never in the interior.

Adult Male, in summer.

Bill a little shorter than the head, rather stout, compressed, tapering,

straightish, being recurvate in a slight degree. Upper mandible with the dorsal

line very slightly concave, the nasal groove extending to the middle, the sides

beyond it sloping, the tip depressed and blunted. Nostrils sub-basal,

linear-oblong, pervious. Lower mandible with the angle short, the dorsal line

ascending and slightly convex, the sides convex, the edges sharp, the tip

depressed and blunted.

Head small, ovate; eyes of moderate size. Neck of ordinary length. Body

rather full. Feet of moderate length, stout; tibia bare at the lower part, and

covered with reticulated scales; tarsus roundish, with numerous broad anterior

scutella; toes four, the first very small, and placed higher than the rest; the

anterior toes free to the base, distinctly margined on both edges, the inner toe

a little shorter than the outer, the third or middle toe considerably longer;

claws rather small, arcuate, compressed, blunted.

Plumage full, soft, rather dense, and glossy; feathers on the hind neck

blended, and rather narrow, on the other parts ovate. Wings long, pointed, of

moderate breadth; primaries with strong shafts, rather broad, narrowed towards

the end, the first longest, the rest rapidly decreasing; outer secondaries

incurved, obliquely rounded; inner elongated, one of them extending to half an

inch of the tip of the longest primary, when the wing is closed. Tail rather

short, slightly rounded, of twelve moderately broad, rounded feathers.

Bill black. Iris hazel. Feet deep orange-red, claws black. Plumage

variegated with white, black, brown, and red. Upper parts of the head and nape

streaked with black and reddish-white; a broad band of white crosses the

forehead, passes over the eyes, and down the sides of the neck, the hind part of

which is reddish-white, faintly mottled with dusky; a frontal band of black

curves downwards before the eye, enclosing a white patch on the lore, and

meeting another black band glossed with blue, which proceeds down the neck, from

the base of the lower mandible, enlarging behind the ear, covering the whole

anterior part of the neck, and passing along the shoulder over the scapulars;

the throat, hind part of the back, the outer scapulars, upper tail-coverts, and

the under parts of the body and wings, white. Anterior smaller wing-coverts

dusky, the rest bright chestnut or brownish-orange, as are the outer webs of the

inner tertiaries; alula, primary coverts, outer secondary coverts and quills

blackish-brown, their inner webs becoming white towards the base; a broad band

of white extends across the wing, including the bases of the primary quills,

excepting the outer four, and the ends of the secondary coverts; the shafts of

the primaries white. Tail white, with a broad blackish-brown bar towards the

end, broader in the middle, the tips white. A dusky band crosses the rump.

Length to end of tail 9 inches, to end of wings 8 3/8, to end of claws 10;

extent of wings 18 3/8; along the ridge (9 1/2)/12, along the edge of lower

mandible 11/12; wing from flexure 6 1/12; tail 2 4/12; tarsus 11/12; hind toe

(2 1/2)/12, its claw 2/12; middle toe 10/12, its claw (3 1/2)/12. Average

weight of three specimens 3 2/3 oz.

Male, in winter.

In winter, the throat, lower parts, middle of the back, upper tail-coverts,

and band across the wing, are white, as in summer; the tail and quills are also

similarly coloured, but the inner secondaries are destitute of red, of which

there are no traces on the upper parts, they being of a dark greyish-brown

colour, the feathers tipped or margined with paler; the outer edges of the outer

scapulars, and some of the smaller wing-coverts, white; on the sides and fore

part of the neck the feathers blackish, with white shafts.

Individuals vary much according to age and sex, as well in size as in

colour, scarcely two in summer plumage being found exactly similar.

In a male bird, the tongue is (6 1/2)/12 of an inch in length, sagittate

and papillate at the base, concave above, narrow, and tapering to the point.

The oesophagus is 4 1/4 inches long, inclines to the right, is rather narrow,

and uniform, its diameter (4 1/2)/12. Proventriculus oblong, 8/12 in length,

5/12 in breadth, its glandules cylindrical. Stomach oblong, 11/12 in length,

its cuticular lining very tough and hard, with broad longitudinal rugae, its

lateral muscles moderately large. Intestine 17 1/2 inches long, slender,

varying in diameter from (2 1/2)/12 to (1 1/2)/12; rectum 1 1/2; coeca 1 8/12,

11/12 in diameter at the commencement, 2/12 toward the end; cloaca globular.

The trachea is 3 1/4 inches long, 2 (1/2)/12 in breadth, contracts to 1/12;

its lateral muscles very thin; sterno-tracheal slender, a pair of

tracheali-bronchial muscles. The rings are very thin and unossified, 104 in

number. Bronchi of moderate length, with about 15 half rings.

In a female, the oesophagus is 4 1/4 inches long, the intestine 18. In

both individuals the stomach contained fragments of shells, and claws of very

small crabs, which were also found in the intestine, although there more

comminuted.

| Next >> |