| Family XXXVI. SCOLOPACINE. SNIPES. GENUS VII. MICROPTERA, Nutt. WOODCOCK OR BOGSUCKER. |

Next >> |

Family |

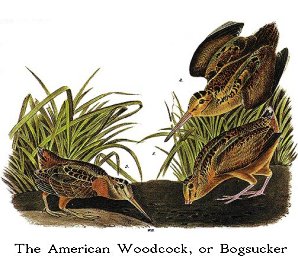

THE AMERICAN WOODCOCK, OR BOGSUCKER. [American Woodcock.] |

| Genus | MICROPTERA AMERICANA, Aud. [Scolopax minor.] |

There is a kind of innocent simplicity in our Woodcock,

which has often excited in me a deep feeling of anxiety, when I witnessed the rude and

unmerciful attempts of mischievous boys, on meeting a mother bird in vain

attempting to preserve her dear brood from their savage grasp. She scarcely

limps, nor does she often flutter along the ground, on such occasions; but with

half extended wings, inclining her head to one side, and uttering a soft murmur,

she moves to and fro, urging her young to hasten towards some secure spot beyond

the reach of their enemies. Regardless of her own danger, she would to all

appearance gladly suffer herself to be seized, could she be assured that by such

a sacrifice she might ensure the safety of her brood. On an occasion of this

kind, I saw a female Woodcock lay herself down on the middle of a road, as if

she were dead, while her little ones, five in number, were endeavouring on

feeble legs to escape from a pack of naughty boys, who had already caught one of

them, and were kicking it over the dust in barbarous sport. The mother might

have shared the same fate, had I not happened to issue from the thicket, and

interpose in her behalf.

The American Woodcock, although allied to our Common Snipe, Scolopax

Wilsonii, differs essentially from it in its habits, even more than in form.

The former is a much gentler bird than the latter, and although both see at

night, the Woodcock is more nocturnal than the Snipe. The latter often, without

provocation or apparent object, migrates or takes long and elevated flights

during the day; but the Woodcock rarely takes flight at this time, unless forced

to do so to elude its enemies, and even then removes only to a short distance.

When rambling unconcernedly, it rarely passes high above the tree tops, or is

seen before the dusk or after the morning twilight, when it flies rather low,

generally through the woods; and its travels are altogether performed under

night. The largeness of its eyes, as compared with those of the Snipe, might of

itself enable one to form such a conclusion; but there is moreover a difference

in the habits of the Woodcock and Snipe, which I have been surprised at not

finding mentioned by WILSON, who certainly was an acute observer. It is that

the Woodcock, although a prober of the mire, frequently alights in the interior

of extensive forests, where little moisture can be seen, for the purpose of

turning up the dead leaves with its bill, in search of food beneath them, in the

manner of the Passenger Pigeon, various Grakles, and other birds. This the

Snipe, I believe, has never been observed to do. Indeed, although the latter at

times alights on the borders of pools or streams overhung by trees, it never

flies through the woods.

The American Woodcock, which in New Brunswick is named the Bogsucker, is

found dispersed in abundance during winter over the southern parts of the Union,

and now and then, in warm and sequestered places, even in the Middle Districts.

Its stay in any portion of the country at this period, seems to depend

altogether on the state of the weather. In the Carolinas, or even in Lower

Louisiana, after a night of severe frost, I have found their number greatly

diminished in places where they had been observed to be plentiful the day

before. The limits of its northern migrations at the commencement of the

breeding season, are yet unascertained. When in Newfoundland I was assured that

it breeds there; but I met with none either in that country or in Labrador,

although it is not rare in the British Provinces of New Brunswick and Nova

Scotia during summer. From the beginning of March until late in October, this

bird may be found in every district of the Union that affords places suited to

its habits; and its numbers, I am persuaded, are much greater than is usually

supposed. As it feeds by night, it is rarely met with by day, unless by a

sportsman or gunner, who may be engaged in pursuing it for pleasure or profit.

It is, however, killed in almost incredible numbers, from the beginning of July

until late in winter, in different parts of the Union, and our markets are amply

supplied with it during its season. You may at times see gunners returning from

their sports with a load of Woodcocks, composed of several dozens; nay, adepts

in the sport have been known to kill upwards of a hundred in the course of a

day, being assisted by relays of dogs, and perhaps a change of guns. In Lower

Louisiana, they are slaughtered under night by men carrying lighted torches,

which so surprise the poor things that they stand gazing on the light until

knocked dead with a pole or cane. This, however, takes place only on the sugar

and cotton plantations.

At the time when the Woodcocks are travelling from the south towards all

parts of the United States, on their way to their breeding places, these birds,

although they migrate singly, follow each other with such rapidity, that they

might be said to arrive in flocks, the one coming directly in the wake of the

other. This is particularly observable by a person standing on the eastern

banks of the Mississippi or the Ohio, in the evening dusk, from the middle of

March to that of April, when almost every instant there whizzes past him a

Woodcock, with a velocity equalling that of our swiftest birds. See them flying

across and low over the broad stream; the sound produced by the action of their

wings reaches your ear as they approach, and gradually dies away after they have

passed and again entered the woods. While travelling with my family, in the

month of October, through New Brunswick and the northern part of the State of

Maine, I saw the Woodcocks returning southward in equal numbers late in the

evenings, and in the same continuous manner, within a few yards or even feet of

the ground, on the roads or through the woods.

This species finds itself accommodated in the warmer parts of the United

States, as well as in high northern latitudes, during the breeding season: it

is well known to reproduce in the neighbourhood of Savannah in Georgia, and near

Charleston in South Carolina. My friend JOHN BACHMAN has known thirty young

ones, not yet fully fledged, to have been killed in the vicinity of the latter

place in one day. I have never found its nest in Louisiana, but I have

frequently fallen in with it in the States from Mississippi to Kentucky, in

which latter country it breeds abundantly. In the Middle Districts, the

Woodcock begins to pair in the end of March; in the southern a month earlier.

At this season, its curious spiral gyrations, while ascending or descending

along a space of fifty or more yards of height, in the manner described in the

article on the Snipe, when it utters a note different from the cry of that bird,

and somewhat resembling the word kwauk, are performed every evening and morning

for nearly a fortnight. While on the ground, at this season as well as in

autumn, the male not unfrequently repeats this sound, as if he were calling to

others in his neighbourhood, and on hearing it answered, immediately flies to

meet the other bird, which in the same manner advances toward him. On observing

the Woodcock while in the act of emitting these notes, you would imagine he

exerted himself to the utmost to produce them, its head and bill being inclined

towards the ground, and a strong forward movement of the body taking place at

the moment the kwauk reaches your ear. This over, the bird jerks its

half-spread tail, then erects itself, and stands as if listening for a few

moments, when, if the cry is not answered, it repeats it. I feel pretty

confident that, in spring, the female, attracted by these sounds, flies to the

male; for on several occasions I observed the bird that had uttered the call

immediately caress the one that had just arrived, and which I knew from its

greater size to be a female. I am not, however, quite certain that this is

always the case, for on other occasions I have seen a male fly off and alight

near another, when they would immediately begin to fight, tugging at and pushing

each other with their bills, in the most curious manner imaginable.

The nest, which is formed of dried leaves and grass, without much apparent

care, is usually placed in some secluded part of the woods, at the foot of some

bush, or by the side of a fallen trunk. In one instance, near Camden, in New

Jersey, I found one in a small swamp, on the upper part of a log, the lower

portion of which was covered with water to the height of several inches. The

eggs, which are laid from February to the first of June, according to the

latitude of the place selected, are usually four, although I have not very

unfrequently found five in a nest. They average one inch and five and a half

eighths in length, by one inch and an eighth in breadth, are smooth, of a dull

yellowish clay colour, varying in depth, and irregularly but pretty thickly

marked with patches of dark brown, and others of a purple tint.

The young run about as soon as they emerge from the shell. To my

astonishment, I once met with three of them on the border of a sand-bar on the

Ohio, without their parent, and to all appearance not more than half a day old.

I concealed myself near them for about half an hour, during which time the

little things continued to totter about the edge of the water, as if their

mother had gone that way. During the time I remained I did not see the old

bird, and what became of them I know not. The young birds are at first covered

with down of a dull yellowish-brown colour, then become streaked with deeper

umber tints, and gradually acquire the colours of the old. At the age of from

three to four weeks, although not fully fledged, they are able to fly and escape

from their enemies, and when they are six weeks old, it requires nearly as much

skill to shoot them on wing as if they were much older. At this age they are

called stupid by most people; and, in fact, being themselves innocent, and not

yet having had much experience, they are not sufficiently aware of the danger

that may threaten them, when a two-legged monster, armed with a gun, makes his

appearance. But, reader, observe an old cock on such occasions: there he lies,

snugly squatted beneath the broad leaves of that "sconk cabbage" or dock. I see

its large dark eye meeting my glance; the bird shrinks as it were within its

usual size, and, in a crouching attitude, it shifts with short steps to the

other side. The nose of the faithful pointer marks the spot, but unless you are

well acquainted with the ways of Woodcocks, it has every chance of escaping from

you both, for at this moment it runs off through the grass, reaches a clump of

bushes, crosses it, and, taking to wing from a place toward which neither you

nor your dog have been looking, you become flustered, take a bad aim, and lose

your shot.

Thousands of persons besides you and myself are fond of Woodcock shooting.

It is a healthful but at times laborious sport. You well know the places where

the birds are to be found under any circumstances; you are aware that, if the

weather has been for some time dry, you must resort to the damp meadows that

border the Schuylkill, or some similar place; that should it be sultry, the

covered swamps are the spots which you ought to visit; but if it be still

lowering after continued rain, the southern sides of gentle hills will be found

preferable; that if the ground is covered with snow, the oozy places visited by

the Snipe are as much resorted to by the Woodcock; that after long frost, the

covered thickets along some meandering stream are the places of their retreat;

and you are aware that, at all times, it is better for you to have a dog of any

kind than to go without a dog at all. Well, you have started a bird, which with

easy flaps flies before you in such a way that if you miss it, your companion

certainly will not. Should he, however, prove as unsuccessful as yourself, you

may put up the bird once, twice, or thrice in succession, for it will either

alight in some clump of low trees close by, or plunge into a boggy part of the

marsh. As you advance towards him, you may chance to put up half a score more,

and stupid though you should be, you must be a shot indeed if you do not

bring some one of them to the ground. Aye, you have done it, and are improving

at the sport, and you may be assured that the killing of Woodcocks requires more

practice than almost any other kind of shooting. The young sportsman shoots too

quick, or does not shoot at all, in both which cases the game is much better

pleased than you are yourself. But when once you have acquired the necessary

coolness and dexterity, you may fire, charge and fire again from morning till

night, and go on thus during the whole of the Woodcock season.

Now and then, the American Woodcock, after being pursued for a considerable

time, throws itself into the centre of large miry places, where it is very

difficult for either man or dog to approach it; and indeed if you succeed, it

will not rise unless you almost tread upon it. In such cases I have seen dogs

point at them, when they were only a few inches distant, and after several

minutes seize upon them. When in clear woods, such as pine barrens, the

Woodcock on being put up flies at times to a considerable distance, and then

performs a circuit and alights not far from you. It is extremely attached to

particular spots, to which it returns after being disturbed.

Its flight is performed by constant rather rapid beats of the wings, and

while migrating it passes along with great speed. I am inclined to think its

flight is greatly protracted, on account of the early periods at which it

reaches Maine and New Brunswick:--I may be wrong, but I am of opinion that at

such times it flies faster than our little Partridge. In proceeding, it

inclines irregularly to the right and left at the end of every few yards; but

when it has been put up after having settled for awhile, it rises as if not

caring about you, and at a slow pace goes a few yards and alights again, runs a

few steps and squats to await your departure. It is less addicted to wading

through the water than the Snipe, and never searches for food in salt marshes or

brackish places. Rivulets that run through thickets, and of which the margins

are muddy or composed of oozy ground, are mostly preferred by it; but, as I have

already said, its place of abode depends upon the state of the weather and the

degree of temperature.

The food of the Woodcock consists principally of large earthworms, of which

it swallows as many in the course of a night as would equal its own weight; but

its power of digestion is as great as that of the Heron's, and it is not very

often that on opening one you find entire worms in its stomach. It obtains its

food by perforating the damp earth or mire, and also by turning the dead leaves

in the woods, and picking up the worms that lie beneath them. In captivity,

Woodcocks very soon accustom themselves to feed on moistened corn meal, bits of

cheese, and vermicelli soaked in water. I have seen some that became so gentle

as to allow their owner to caress them with the hand. On watching several

individuals probing mud in which a number of earthworms had been introduced, in

a tub placed in a room partially darkened, I observed the birds plunge their

bills up to the nostrils, but never deeper; and from the motion of the parts at

the base of the mandibles, I concluded that the bird has the power of working

their extremities so as to produce a kind of vacuum, which enables it to seize

the worm at one end, and suck it into its throat before it withdraws its bill,

as do Curlews and Godwits. The quickness of their sight on such occasions was

put to the test by uncovering a cat placed in the corner of the room, at the

same height above the floor as the surface of the mud which filled the tub, when

instantly the Woodcock would draw out its bill, jerk up its tail, spread it out,

leap upon the floor, and run off to the opposite corner. At other times, when

the cat was placed beneath the level of the bird, by the whole height of the

tub, which was rather more than a foot, the same result took place; and I

concluded that the elevated position of this bird's eye was probably intended to

enable it to see its enemies at a considerable distance, and watch their

approach, while it is in the act of probing, and not to protect that organ from

the mire, as the Woodcock is always extremely clean, and never shews any earth

adhering to the feathers about its mouth.

How comfortable it is when fatigued and covered with mud, your clothes

drenched with wet, and your stomach aching for food, you arrive at home with a

bag of Woodcocks, and meet the kind smiles of those you love best, and which are

a thousand times more delightful to your eye, than the savoury flesh of the most

delicate of birds can be to your palate. When you have shifted your clothes,

and know that on the little round table already spread, you will ere long see a

dish of game, which will both remove your hunger and augment the pleasure of

your family; when you are seated in the midst of the little group, and now see

some one neatly arrayed introduce the mess, so white, so tender, and so

beautifully surrounded by savoury juice; when a jug of sparkling Newark cider

stands nigh; and you, without knife or fork, quarter a Woodcock, ah,

reader!--But alas! I am not in the Jerseys just now, in the company of my

generous friend EDWARD HARRIS; nor am I under the hospitable roof of my equally

esteemed friend JOHN BACHMAN. No, reader, I am in Edinburgh, wielding my iron

pen, without any expectation of Woodcocks for my dinner, either to-day or

to-morrow, or indeed for some months to come.

SCOLOPAX MINOR, Gmel. Syst. Nat., vol. i. p. 661.

WOODCOCK, Scolopax minor, Wils. Amer. Orn., vol. vi. p. 40.

SCOLOPAX MINOR, Bonap. Syn., p. 331.

LESSER WOODCOCK, Nutt. Man., vol. ii. p. 194.

AMERICAN WOODCOCK, Scolopax minor, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. iii. p. 474.

Male, 11, 16. Female, 11 7/12, 17 1/4.

Distributed throughout the country. Extremely abundant in the Middle and

Eastern Districts, as well as in the interior, where it breeds, as far as Nova

Scotia. Equally abundant in winter in the Southern States, though many migrate

southward.

Adult Male.

Bill double the length of the head, straight, slender, tapering,

sub-trigonal and deeper than broad at the base, slightly depressed towards the

end. Upper mandible with the dorsal line straight, the ridge narrow, towards

the end flattened, the sides nearly erect, sloping outward towards the soft

obtuse edges, the tip blunt, knob-like, and longer than that of the lower

mandible. Nostrils basal, lateral, linear, very small. Lower mandible broader

than the upper, the angle very long and narrow, the dorsal line straight, the

back broadly rounded, the sides marked with a broad groove, sloping inwards at

the base, outwards towards the end, the edges soft and obtuse, the tip rounded.

Head rather large, oblong, narrowed anteriorly; eyes large, and placed

high. Neck short and thick. Body rather full. Feet rather short; tibia

feathered to the joint; tarsus rather short, compressed, anteriorly covered with

numerous scutella, laterally and behind with sub-hexagonal scales, and having a

row of small scutelliform scales along the outer side behind. Toes free,

slender, the first very small, the second slightly shorter than the fourth, the

third much longer and exceeding the tarsus in length; all scutellate above,

marginate, flattish beneath. Claws very small, arched, acute, that of hind toe

extremely small, of middle toe with a thin inner edge.

Plumage very soft, elastic, blended; of the fore part of the head very

short, of the neck full. Wings short, rounded; the fourth and fifth quills

about equal and longest, the first three extraordinarily attenuated, being in

fact sub-linear, narrower beyond the middle, the inner web slightly enlarged

towards the end, the first as long as the seventh; secondaries broad, the outer

a little incurved and rounded, the inner tapering and elongated. Tail very

short, wedge-shaped, of twelve narrow feathers, which taper towards the rounded

point.

Bill light yellowish-brown, dusky towards the end. Iris brown. Feet

flesh-coloured; claws brownish-black. The forehead is yellowish-grey, with a

few dark mottlings in the centre; on the upper part of the head are two broad

brackish-brown transverse bands, and on the occiput two narrower, separated by

bands of light red; a brownish-black loral band, and a narrow irregular line of

the same across the cheek and continued to the occiput. The upper parts are

variegated with brownish-black, light yellowish-red, and ash-grey; there are

three broad longitudinal bands of the first colour, barred with the second, down

the back, separated by two of the last. The inner wing-coverts and secondary

quills are similarly barred; the outer pale greyish-red, faintly barred with

dusky. The quills are greyish-brown, tipped with dull grey, the secondaries

spotted on the outer web with dull red. Upper tail-coverts barred;

tail-feathers brownish-black, their tips grey, their outer edges mottled with

reddish. The sides of the neck are grey, tinged with red; the lower parts in

general light red, tinged with grey on the breast, on the sides and lower

wing-coverts deeper; the lover tail-coverts with a central dusky line, and the

tip white.

Length to end of tail 11 inches, to end of wings 9 1/2; wing from flexure

5 1/4; tail 2 4/12; bill along the ridge 2 8/12, along the edge of lower

mandible 2 (5 1/2)/12; tarsus 1 2/12; middle toe 1 5/12, its claw 1/4. Weight

6 1/4 oz.

Adult Female.

The female, which is considerably larger, has the same colours as the male.

Length to end of tail 11 7/12, to end of wings 10 5/12, to end of claws

13 4/12; wing from flexure 5 4/12; tail 2 4/12; bill along the ridge 2 10/12;

along the edge of lower mandible 2 (6 1/2)/12; tarsus 1 2/12; middle toe 2 5/12,

its claw 1/4. Weight 8 1/2 oz.

Young fledged.

The young, when fully fledged, is similar to the old female.

| Next >> |