| Family XXXVI. SCOLOPACINE. SNIPES. GENUS VIII. RECURVIROSTRA, Linn. AVOCET. |

Next >> |

Family |

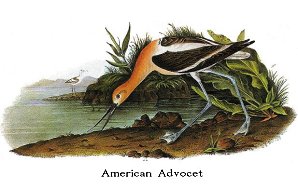

AMERICAN ADVOSET. [American Avocet.] |

| Genus | RECURVIROSTRA AMERICANA, Linn. [Recurvirostra americana.] |

The fact of this curious bird's breeding in the interior

of our country accidentally became known to me in June 1814. I was at the time travelling on

horseback from Henderson to Vincennes in the State of Indiana. As I approached

a large shallow pond in the neighbourhood of the latter town, I was struck by

the sight of several Advosets hovering over the margins and islets of the pond

and although it was late, and I was both fatigued and hungry, I could not resist

the temptation of endeavouring to find the cause of their being so far from the

sea. Leaving my horse at liberty, I walked toward the pond, when, on being at

once assailed by four of the birds, I felt confident that they had nests, and

that their mates were either sitting or tending their young. The pond, which

was about two hundred yards in length, and half as wide, was surrounded by tall

bulrushes extending to some distance from the margin. Near its centre were

several islets, eight or ten yards in length, and disposed in a line. Having

made my way through the rushes, I found the water only a few inches deep; but

the mud reached above my knees, as I carefully advanced towards the nearest

island. The four birds kept up a constant noise, remained on wing, and at times

dived through the air until close to me, evincing their displeasure at my

intrusion. My desire to shoot them however was restrained by my anxiety to

study their habits as closely as possible; and as soon as I had searched the

different inlets, and found three nests with eggs, and a female with her brood,

I returned to my horse, and proceeded to Vincennes, about two miles distant.

Next morning at sunrise I was snugly concealed amongst the rushes, with a fair

view of the whole pond. In about an hour the male ceased to fly over me, and

betook themselves to their ordinary occupations, when I noted the following

particulars.

On alighting, whether on the water or on the ground, the American Advoset

keeps its wings raised until it has fairly settled. If in the water, it stands

a few minutes balancing its head and neck, somewhat in the manner of the

Tell-tale Godwit. After this it stalks about searching for food, or runs after

it, sometimes swimming for a yard or so while passing from one shallow to

another, or wading up to its body, with the wings partially raised. Sometimes

they would enter among the rushes, and disappear for several minutes. They kept

apart, but crossed each other's path in hundreds of ways, all perfectly silent,

and without shewing the least symptom of enmity towards each other, although

whenever a Sandpiper came near, they would instantly give chase to it. On

several occasions, when I purposely sent forth a loud shrill whistle without

stirring, they would suddenly cease from their rambling, raise up their body and

neck, emit each two or three notes, and remain several minutes on the alert,

after which they would fly to their nests, and then return. They search for

food precisely in the manner of the Roseate Spoonbill, moving their heads to and

fro sideways, while their bill is passing through the soft mud; and in many

instances, when the water was deeper, they would immerse their whole head and a

portion of the neck, as the Spoonbill and Red-breasted Snipe are wont to do.

When, on the contrary, they pursued aquatic insects, such as swim on the

surface, they ran after them, and on getting up to them, suddenly seized them by

thrusting the lower mandible beneath them, while the other was raised a good way

above the surface, much in the manner of the Black Shear-water, which, however,

performs this act on wing. They were also expert at catching flying insects,

after which they ran with partially expanded wings.

I watched them as they were thus engaged about an hour, when they all flew

to the islets where the females were, emitting louder notes than usual. The

different pairs seemed to congratulate each other, using various curious

gestures; and presently those which had been sitting left the task to their

mates and betook themselves to the water, when they washed, shook their wings

and tail, as if either heated or tormented by insects, and then proceeded to

search for food in the manner above described. Now, reader, wait a few moments

until I eat my humble breakfast.

About eleven o'clock the heat had become intense, and the Advosets gave up

their search, each retiring to a different part of the pond, where, after

pluming themselves, they drew their heads close to their shoulders, and remained

perfectly still, as if asleep, for about an hour, when they shook themselves

simultaneously, took to wing, and rising to the height of thirty or forty yards,

flew off towards the waters of the Wabash river.

I was now desirous of seeing one of the sitting birds on its nest, and

leaving my hiding place, slowly, and as silently as possible, proceeded toward

the nearest islet on which I knew a nest to be, having the evening before, to

mark the precise spot, broken some of the weeds, which were now withered by the

heat of the sun. You, good reader, will not, I am sure, think me prolix; but as

some less considerate persons may allege that I am tediously so, I must tell

them here that no student of Nature ever was, or ever can be, too particular

while thus marking the precise situation of a bird's nest. Indeed, I myself

have lost many nests by being less attentive. After this short but valuable

lecture, you and I will do our best to approach the sitting bird unseen by it.

Although a person can advance but slowly when wading through mud and water

knee-deep, it does not take much time to get over forty or fifty yards, and thus

I was soon on the small island where the Advoset was comfortably seated on her

nest. Softly and on all four I crawled toward the spot, panting with heat and

anxiety. Now, reader, I am actually within three feet of the unheeding

creature, peeping at her through the tall grasses. Lovely bird! how innocent,

how unsuspecting, and yet how near to thine enemy, albeit he be an admirer of

thy race! There she sits on her eggs, her head almost mournfully sunk among the

plumage, and her eyes, unanimated by the sight of her mate, half closed, as if

she dreamed of future scenes. Her legs are bent beneath her in the usual

manner. I have seen this, and I am content. Now she observes me, poor thing,

and off she scrambles,--running, tumbling, and at last rising on wing, emitting

her clicking notes of grief and anxiety, which none but an inconsiderate or

callous-hearted person could hear without sympathizing with her.

The alarm is sounded, the disturbed bird is floundering hither and thither

over the pool, now lying on the surface as if ready to die, now limping to

induce me to pursue her and abandon her eggs. Alas, poor bird! Until that day

I was not aware that gregarious birds, on emitting cries of alarm, after having

been scared from their nest, could induce other incubating individuals to leave

their eggs also, and join in attempting to save the colony. But so it was with

the Advosets, and the other two sitters immediately rose on wing and flew

directly at me, while the one with the four younglings betook herself to the

water, and waded quickly off, followed by her brood, which paddled along

swimming, to my astonishment, as well as ducklings of the same size.

How far such cries as those of the Advoset may be heard by birds of the same

species I cannot tell; but this I know, that the individuals which had gone

toward the Wabash reappeared in a few minutes after I had disturbed the first

bird, and hovered over me. But now, having, as I thought, obtained all

desirable knowledge of these birds, I shot down five of them, among which I

unfortunately found three females.

The nests were placed among the tallest grasses, and were entirely composed

of the same materials, but dried, and apparently of a former year's growth.

There was not a twig of any kind about them. The inner nest was about five

inches in diameter, and lined with fine prairie grass, different from that found

on the islets of the pond, and about two inches in depth, over a bed having a

thickness of an inch and a half. The islets did not seem to be liable to

inundation, and none of the nests exhibited any appearance of having been

increased in elevation since the commencement of incubation, as was the case

with those described by WILSON. Like those of most waders, the eggs were four

in number, and placed with the small ends together. They measured two inches in

length, one inch and three-eighths in their greatest breadth, and were, exactly

as WILSON tells us, "of a dull olive-colour, marked with large irregular

blotches of black, and with others of a fainter tint." To this I have to add,

that they are pear-shaped and smooth. As to the time of hatching, I know

nothing.

Having made my notes, and picked up the dead birds, I carefully waded

through the rushes three times around the whole pond, but, being without my dog,

failed in discovering the young brood or their mother. I visited the place

twice the following day, again waded round the pond, and searched all the

islets, but without success: not a single Advoset was to be seen; and I am

persuaded that the mother of the four younglings had removed them elsewhere.

Since that time my opportunities of meeting with the American Advoset have

been few. On the 7th of November, 1819, while searching for rare birds a few

miles from New Orleans, I shot one which I found by itself on the margin of

Bayou St. John. It was a young male, of which I merely took the measurements

and description. It was very thin, and had probably been unable to proceed

farther south. Its stomach contained only two small fresh-water snails and a

bit of stone. In May 1829, 1 saw three of these birds at Great Egg Harbour, but

found no nests, although those of the Long legged Advoset of WILSON were not

uncommon. My friend JOHN BACHMAN considers them as rare in South Carolina,

where, however, he has occasionally seen some on the gravelly shores of the sea

islands.

On the 16th of April, 1837, my good friend Captain NAPOLEON COSTE, of the

United States Revenue Cutter the Campbell, on board of which I then was, shot

three individuals of this species on an immense sand-bar, intersected by pools,

about twelve miles from Derniere Island on the Gulf of Mexico, and brought them

to me in perfect order. They were larger, and perhaps handsomer, than any that

I have seen; and had been killed out of a flock of five while feeding. He saw

several large flocks on the same grounds, and assured me that the only note they

emitted was a single whistle. He also observed their manner of feeding, which

he represented as similar to that described above.

My friend THOMAS NUTTALL says in a note, that be "found this species

breeding on the islands of shallow ponds throughout the Rocky Mountains about

midsummer. They exhibited great fear and clamour at the approach of the party,

but no nests were found, they being then under march." Dr. RICHARDSON states,

that it is abundant on the Saskatchewan Plains, where it frequents shallow

lakes, and feeds on insects and small fresh-water crustacea.

The flight of the American Advoset resembles that of the Himantopus

nigricollis. Both these birds pass through the air as if bent on removing to a

great distance, much in the manner of the Tell-tale Godwit, or with an easy,

rather swift and continued flight, the legs and neck fully extended. When

plunging towards an intruder, it at times comes downwards, and passes by you,

with the speed of an arrow from a bow, but usually in moving off again, it

suffers its legs to hang considerably. I have never seen one of them exhibit

the bending and tremulous motions of the legs spoken of by writers, even when

raised suddenly from the nest; and I think that I am equally safe in saying,

that the bill has never been drawn from a fresh specimen, or before it has

undergone a curvature, which it does not shew when the bird is alive. The notes

of this bird resemble the syllable click, sometimes repeated in a very hurried

manner, especially under alarm.

AMERICAN AVOCET, Recurvirostra Americana, Wils. Amer. Orn., vol. vii.p. 126.

RECURVIROSTRA AMERICANA, Bonap. Syn., p. 394.

RECURVIROSTRA AMERICANA, American Avocet, Swains. and Rich. F. Bor. Amer.,vol. ii. p. 375.

AMERICAN AVOCET, Nutt. Man., vol. ii. p. 74.

AMERICAN AVOCET, Recurvirostra Americana, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. iv.p. 168.

Male, 18, 30 5/8.

Passes along the coast from Texas northward, in small numbers, a few

breeding in New Jersey. Indiana, Illinois, and Missouri. Abundant in the Rocky

Mountains and the Fur Countries. Migratory.

Adult Male.

Bill more than twice the length of the head, very slender, much depressed,

tapering to a point, and slightly recurved. Upper mandible with the dorsal line

straight for half its length, then a little curved upwards, and at the tip

slightly decurved, the ridge broad and flattened, the edges rather thick, the

nasal groove rather long and very narrow. Nostrils linear, basal, pervious.

Lower mandible with the angle long and very narrow, the dorsal line slightly

curved upwards, the point very slender, extremely thin and a little curved

upwards.

Head small, rounded above, rather compressed. Neck long. Body compact,

ovate. Legs very long, slender; tibia elongated, bare for half its length, and

reticulated; tarsus very long, compressed, reticulated with hexagonal scales;

toes rather short, the first extremely small; outer toe a little longer than

inner; the anterior toes connected by webs of which the anterior margin is

deeply concave, the lateral toes thickly margined. Claws very small,

compressed, rather blunt.

Plumage soft and blended. Wings long, of moderate breadth, pointed;

primaries straightish, tapering, the first longest, the rest rapidly graduated;

secondaries broad, incurved, the outer rounded, the rest becoming pointed, the

inner elongated and tapering. Tail short, even, of twelve rather narrow,

rounded feathers.

Bill black. Iris bright carmine. Feet light blue, webs flesh-coloured

towards their edges, claws black. Head, neck, and fore part of breast,

reddish-buff, the parts around the base of the bill and the eye nearly white.

The back is white; but on its fore part is a longitudinal band of brownish-black

elongated feathers on each side, and the inner scapulars are of the same colour,

the outer and the anterior edge of the wing being white. The wing

brownish-black, with a broad band of white formed by the tips of the secondary

coverts, four of the inner secondaries, and the basal part, with the inner webs

and outer edges of the rest. The under parts white, excepting some of the

primary quills and some of their coverts, which are greyish-brown.

Length to end of tail 18 inches, to end of wings 18 1/2, to end of claws

23 1/2; extent of wings 30 5/8; wing from flexure 9 1/2; tail 3 1/2; bill along

the ridge 3 3/4 bare part of the tibia 2 3/12; tarsus 3 5/8; hind toe and claw

3/12; middle toe and claw 1 10/12; breadth of foot extended 2 5/8. Weight

16 3/4 oz.

The Female is similar to the male, but somewhat smaller.

Young in winter.

The young in winter is similar to the adult, but with the head and neck

white, the dark colours of a browner tint.

Length to end of tail 18 inches, to end of wings 18 1/2; extent of wings

30 1/2.

Weight 13 oz.

In structure the Advosets are similar to the Numenii and Totani. In an

adult female the tongue is very short in proportion to the length of the bill,

being only if inches long, slightly emarginate at the base with a few conical

papillae, slender, tapering to a point, horny on the back, and flattened above.

On the palate are two longitudinal series of blunt papillae. The posterior

aperture of the nares is linear, 10 twelfths long, papillate on the edges. The

oesophagus is 7 inches and 9 twelfths long, inclines to the right side, and when

the neck is bent becomes posterior at the middle, as in the Herons and other

long-necked birds; its diameter 5 twelfths at the upper part, dilated to 8

twelfths previous to its entrance into the thorax. The proventriculus is 1 inch

long and 7 twelfths in diameter; its glandules cylindrical, 1 twelfth long. The

stomach is a gizzard of moderate strength, oblong, 1 1/2 inches in length, 10

twelfths in breadth, its right lateral muscle 4 twelfths thick. Its contents

were remains of small shells. Its inner membrane of moderate thickness, hard,

longitudinally rugous, and deeply tinged with red. The intestine is 3 feet

long, and 4 twelfths in diameter; the rectum 2 inches long; of the coeca one is

2 3/4 inches long, the other 2 1/4, their diameter 2 twelfths.

In another individual the intestine is 3 feet 9 inches long; one of the

coeca 2 3/4 inches, the other 3; the stomach 1 1/2 by 1 1/12. Its contents

small shell-fish and fragments of quartz.

The trachea is 6 1/2 inches long; its rings extremely thin and unossified,

140 in number, its diameter 3 1/4 twelfths, nearly uniform throughout, but

rather narrower in the middle. The lateral muscles are very thin. The bronchi

are short, of about 10 rings.

| Next >> |