| Family XXXVIII. ARDEINAE. HERONS. GENUS I. ARDEA, Linn. HERON. |

Next >> |

Family |

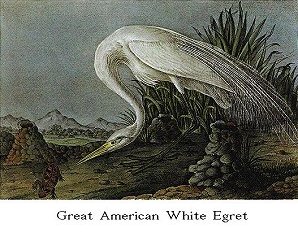

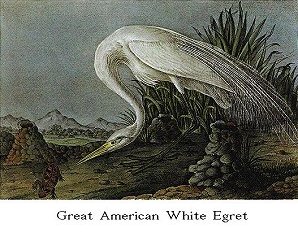

GREAT AMERICAN WHITE EGRET. [Great Egret.] |

| Genus | ARDEA EGRETTA, Gmel. [Casmerodius albus.] |

The truly elegant Heron which now comes to be described, is a constant resident in the Floridas; it migrates eastward sometimes as far as the State of

Massachusetts, and up the Mississippi to the city of Natchez, and is never seen

far inland, by which I mean that its rambles into the interior seldom extend to

more than fifty miles from the sea-shore, unless along the course of our great

rivers. On my way to Texas, in the spring of 1837, I found these birds in

several places along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, and on several of the

islands scattered around that named Galveston, where, as well as in the

Floridas, I was told that they spend the winter.

The Great American Egret breeds along the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, and

our Atlantic States, from Galveston Island in Texas to the borders of the State

of New York, beyond which, although stragglers have been seen, none, in so far

as I can ascertain, have been known to breed. In all low districts that are

marshy and covered with large trees, on the margins of ponds or lakes, the sides

of bayous, or gloomy swamps covered with water, are the places to which it

generally resorts during the period of reproduction; although I have in a few

instances met with their hests on low trees, and on sandy islands at a short

distance from the mainland. As early as December I have observed vast numbers

congregated, as if for the purpose of making choice of partners, when the

addresses of the males were paid in a very curious and to me interesting manner.

Near the plantation Of JOHN BULOW, Esq. in East Florida, I had the pleasure of

witnessing this sort of tournament or dress-ball from a place of concealment not

more than a hundred yards distant. The males, in strutting round the females,

swelled their throats, as Cormorants do at times, emitted gurgling sounds, and

raising their long plumes almost erect, paced majestically before the fair ones

of their choice. Although these snowy beaux were a good deal irritated by

jealousy, and conflicts now and then took place, the whole time I remained, much

less fighting was exhibited than I had expected from what I had already seen in

the case of the Great Blue Heron, Ardea Herodias. These meetings took place

about ten o'clock in the morning, or after they had all enjoyed a good

breakfast, and continued until nearly three in the afternoon, when, separating

into flocks of eight or ten individuals, they flew off to search for food.

These manoeuvres were continued nearly a week, and I could with ease, from a

considerable distance, mark the spot, which was a clear sand-bar, by the descent

of the separate small flocks previous to their alighting there.

The flight of this species is in strength intermediate between that of

Ardea Herodias and A. rufescens, and is well sustained. On foot its movements

are as graceful as those of the Louisiana Heron, its steps measured, its long

neck gracefully retracted and curved, and its silky train reminded one of the

flowing robes of the noble ladies of Europe. The train of this Egret, like that

of other species, makes its appearance a few weeks previous to the love season,

continues to grow and increase in beauty, until incubation has commenced, after

which period it deteriorates, and at length disappears about the time when the

young birds leave the nest, when, were it not for the difference in size, it

would be difficult to distinguish them from their parents. Should you, however,

closely examine the upper plumage of an old bird of either sex, for both possess

the train, you will discover that its feathers still exist, although shortened

and deprived of most of their filaments. Similar feathers are seen in all other

Herons that have a largely developed train in the breeding season. Even the few

plumes hanging from the hind part of the Ardea Herodias, A. Nycticorax, and A.

violacea, are subject to the same rule; and it is curious to see these ornaments

becoming more or less apparent, according to the latitude in which these birds

breed, their growth being completed in the southern part of Florida two months

sooner than in our Middle Districts.

The American Egrets leave the Floridas almost simultaneously about the 1st

of March, and soon afterwards reach Georgia and South Carolina, but rarely the

State of New Jersey, before the middle of May. In these parts the young are

able to fly by the 1st of August. On the Mule Keys off the coast of Florida, I

have found the young well grown by the 8th of May; but in South Carolina they

are rarely hatched until toward the end of that month or the beginning of June.

In these more southern parts two broods are often raised in a season, but in the

Jerseys there is, I believe, never more than one. While travelling, early in

spring, between Savannah in Georgia and Charleston in South Carolina, I saw many

of these Egrets on the large rice plantations, and felt some surprise at finding

them much wilder at that period of their migrations than after they have settled

in some locality for the purpose of breeding. I have supposed this to be caused

by the change of their thoughts on such occasions, and am of opinion that birds

of all kinds become more careless of themselves. As the strength of their

attachment toward their mates or progeny increases through the process of time,

as is the case with the better part of our own species, lovers and parents

performing acts of heroism, which individuals having no such attachment to each

other would never dare to contemplate. In these birds the impulse of affection

is so great, that when they have young they allow themselves to be approached,

so as often to fall victims to the rapacity of man, who, boasting of reason and

benevolence, ought at such a time to respect their devotion.

The American Egrets are much attached to their roosting places, to which

they remove from their feeding grounds regularly about an hour before the last

glimpse of day; and I cannot help expressing my disbelief in the vulgar notion

of birds of this family usually feeding by night, as I have never observed them

so doing even in countries where they were most abundant. Before sunset the

Egrets and other Herons (excepting perhaps the Bitterns and Night Herons) leave

their feeding grounds in small flocks, often composed of only a single family,

and proceed on wing in the most direct course, at a moderate height, to some

secure retreat more or less distant, according to the danger they may have to

guard against. Flock after flock may be seen repairing from all quarters to

these places of repose, which one may readily discover by observing their

course.

Approach and watch them. Some hundreds have reached the well-known

rendezvous. After a few gratulations you see them lower their bodies on the

stems of the trees or bushes on which they have alighted, fold their necks,

place their heads beneath the scapular feathers, and adjust themselves for

repose. Daylight returns, and they are all in motion. The arrangement of their

attire is not more neglected by them than by the most fashionable fops, but they

spend less time at the toilet. Their rough notes are uttered more loudly than

in the evening, and after a very short lapse of time they spread their snowy

pinions, and move in different directions, to search for fiddlers, fish, insects

of all sorts, small quadrupeds or birds, snails, and reptiles, all of which form

the food of this species.

The nest of the Great White Egret, whether placed in a cypress one hundred

and thirty feet high, or on a mangrove not six feet above the water, whether in

one of those dismal swamps swarming with loathsome reptiles, or by the margin of

the clear blue waters that bathe the Keys of Florida, is large, flat, and

composed of sticks, often so loosely put together as to make you wonder how it

can bold, besides itself, the three young ones which this species and all the

larger Herons have at a brood. In a few instances only have I found it

compactly built, it being the first nest formed by its owners. It almost always

overhangs the water, and is resorted to and repaired year after year by the same

pair. The eggs, which are never more than three, measure two inches and a

quarter in length, an inch and five-eighths in breadth, and when newly laid are

smooth, and of a pale blue colour, but afterwards become roughish and faded.

When the nest is placed on a tall tree, the young remain in it, or on its

borders, until they are able to fly; but when on a low tree or bush, they leave

it much sooner, being capable of moving along the branches without fear of being

injured by falling, and knowing that should they slip into the water they can

easily extricate themselves by striking with their legs until they reach either

the shore or the nearest bush, by clinging to the stem of which they soon ascend

to the top.

This Egret is shy and vigilant at all times, seldom allowing a person to

come near unless during the breeding season. If in a rice-field of some extent,

and at some distance from its margins, where cover can be obtained, you need not

attempt to approach it; but if you are intent on procuring it, make for some

tree, and desire your friend to start the bird. If you are well concealed, you

may almost depend on obtaining one in a few minutes, for the Egrets will perhaps

alight within twenty yards or less of you. Once, when I was very desirous of

making a new drawing of this bird, my friend JOHN BACHMAN followed this method,

and between us we carried home several superb specimens.

The long plumes of this bird being in request for ornamental purposes, they

are shot in great numbers while sitting on their eggs, or soon after the

appearance of the young. I know a person who, on offering a double-barrelled

gun to a gentleman near Charleston, for one hundred White Herons fresh killed,

received that number and more the next day.

The Great Egret breeds in company with the Anhinga, the Great Blue Heron,

and other birds of this family. The Turkey Buzzards and the Crows commit

dreadful havoc among its young, as well as those of the other Species. My

friend JOHN BACHMAN gives me the following account of his visit to one of its

breeding places, at the "Round O," a plantation about forty miles from

Charleston: "Our company was composed of BENJAMIN LOGAN, S. LEE, and Dr.

MARTIN. We were desirous of obtaining some of the Herons as specimens for

stuffing, and the ladies were anxious to procure many of their primary feathers

for the purpose of making fans. The trees were high, from a hundred to a

hundred and thirty feet, and our shot was not of the right size; but we

commenced firing at the birds, and soon discovered that we had a prospect of

success. Each man took his tree, and loaded and fired as fast as he could.

Many of the birds lodged on the highest branches of the cypresses, others fell

into the nest, and, in most cases, when shot from a limb, where they had been

sitting, they clung to it for some time before they would let go. One thing

surprised me: it was the length of time it took for a bird to fall from the

place where it was shot, and it fell with a loud noise into the water. Many

wounded birds fell some distance off, and we could not conveniently follow them

on account of the heavy wading through the place. We brought home with us

forty-six of the large White Herons, and three of the Great Blue. Many more

might have been killed, but we became tired of shooting them."

ARDEA EGRETTA, Gmel. Syst. Nat., vol. i. p. 629.

GREAT WHITE HERON, Ardea Egretta, Wits. Amer. Orn., vol. vii. p. 106.

ARDEA ALBA, Bonap. Syn., p. 304.

ARDEA EGRETTA, Wagler, Syst. Av.

GREAT WHITE HERON, Nutt. Man., vol. ii. p. 47.

GREAT AMERICAN EGRET, Ardea Egretta, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. iv. p. 600.

Male, 37, 57.

Resident in Florida, and Galveston Bay in Texas. Migrates in spring

sometimes as fat as Massachusetts; up the Mississippi to Natchez. Breeds in all

intermediate districts. Returns south before winter. Very abundant.

Adult Male, in summer.

Bill much longer than the head, straight, compressed, tapering to a point,

the mandibles nearly equal. Upper mandible with the dorsal line nearly

straight, the ridge broad and slightly convex at the base, narrowed and becoming

rather acute towards the end, a groove from the base to two-thirds of the

length, beneath which the sides are convex, the edges thin and sharp, with a

notch close to the acute tip. Nostrils basal, linear, longitudinal, with a

membrane above and behind. Lower mandible with the angle extremely narrow and

elongated, the dorsal line beyond it ascending and almost straight, the edges

sharp and direct, the tip acuminate.

Head small, oblong, compressed. Neck very long and slender. Body slender

and compressed. Feet very long, tibia elongated, its lower half bare, slender,

covered anteriorly and laterally with hexagonal scales, posteriorly with

scutella; tarsus elongated, compressed, covered anteriorly with numerous

scutella, some of which are divided laterally and posteriorly with angular

scales. Toes of moderate length, rather slender, scutellate above, granulate

beneath; third toe considerably longer than the fourth, which exceeds the

second; the first large; the claws of moderate length, rather strong, arched,

compressed, rather acute, that of the hind toe much larger, the inner edge of

that of the third regularly pectinated.

Space between the bill and eye, and around the latter, bare. Plumage soft,

blended; the feathers oblong, with their filaments generally disunited, unless

on the wings and tail. There is no crest on the head, but the feathers on its

upper and hind part are slightly elongated; those on the lower part of the neck

anteriorly are elongated; and from between the scapulas arises a tuft of

extremely long, slightly decurved feathers, which extend about ten inches beyond

the end of the tail, and have the shaft slightly undulated, the filaments long

and distant. The wing is of moderate length; the primaries tapering but

rounded, the second and third longest, the first slightly shorter than the

fourth; the secondaries broad and rounded, some of the inner as long as the

longest primaries, when the wing is closed. Tail very short, small, slightly

rounded, of twelve rather weak feathers.

Bill bright yellow, as is the bare space between it and the eye; iris pale

yellow; feet and claws black. The plumage is pure white.

Length to end of tail 37 inches, to end of claws 49, to end of wings

57 1/4, to carpus 23 1/2, to end of dorsal plumes 57; bill along the ridge

4 7/12 the edge of lower mandible 5 5/12; wing from flexure 16 1/2; tail 6 1/4;

extent of wings 55; bare part of tibia 3 1/2; tarsus 6 1/12; hind toe 1 1/2, its

claw 1 2/12; second toe 2 8/12, its claw 7/12; third toe 3 11/12, its claw 9/12;

fourth toe 3 2/12, its claw (7 1/2)/12. Weight 2 1/4 lbs.

The Female is similar to the male, but somewhat smaller.

The roof of the mouth is slightly concave, with a median and two lateral

longitudinal ridges, the palate convex, the posterior aperture of the nares

linear, without an adterior slit. The mouth is rather narrow, measuring only 8

twelfths across, but is dilatable to 1 1/2 inches, the branches of the lower

mandible being very elastic. The aperture of the car is very small, being 2

twelfths in diameter, and roundish. The oesophagus is 2 feet 2 inches long, 1

inch and 4 twelfths in diameter, extremely thin, the longitudinal fibres within

the transverse, the inner coat raised into numerous longitudinal ridges. The

oesophagus continues of uniform diameter, and passes as it were directly into

the stomach, there being no enlargement at its termination indicative of the

proventriculus, which however exists, but in a modified form, there being at the

termination of the gullet eight longitudinal series of large mucous crypts,

about half an inch long, and immediately afterwards a continuous belt, 1 1/2

inches in breadth, of small cylindrical mucous crypts with minute apertures.

Beyond this the stomach forms a hemispherical sac 1 1/2 inches in diameter, of a

membranous structure, having externally beneath the cellular coat a layer of

slender muscular fibres, convex towards two roundish tendons, and internally a

soft, thin, smooth lining, perforated by innumerable minute apertures of

glandules. The intestine is very long and extremely slender, measuring 6 feet 7

inches in length, its average diameter 2 twelfths. The rectum, [b d f], is 3

inches long; the cloaca, [d e f], globular, 1 1/2 inches in diameter; the

coecum, [c], single, as in the other Herons, 3 twelfths long, and nearly 2

twelfths in diameter.

The trachea is 1 foot 9 1/4 inches long, of nearly uniform diameter,

flattened a little for about half its length, its greatest breadth 3 1/2

twelfths; the rings 285, the last four rings divided and arched. The contractor

muscles are extremely thin, the sterno-tracheal moderate, and coming off at the

distance of 1 inch from the lower extremity, from which place also there

proceeds to the two last rings a pair of slender inferior laryngeal muscles.

The bronchi are very short, of about two half rings.

TAPAYAXIN.

The animal represented on the plate is the Tapayaxin of HERNANDEZ,

Phrynosoma orbicularis of WIEGMANN, Tapaya orbicularis of CUVIER.

The specimen from which it was drawn was entrusted to my care by my friend

RICHARD HARLAN, M.D., to whom it was presented by Mr. NUTTALL, who found it

in California. A notice respecting this species by Dr. HARLAN will be found

in the American Journal of Science and Arts, vol. xxxi.

| Next >> |