| Family XXXIX. ANATINAE. DUCKS. GENUS II. PHOENICOPTERUS, Linn. FLAMINGO. |

Next >> |

Family |

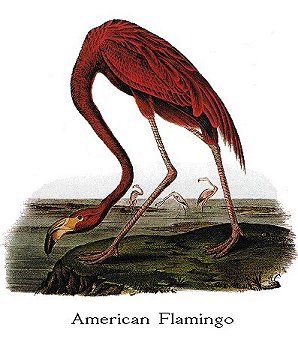

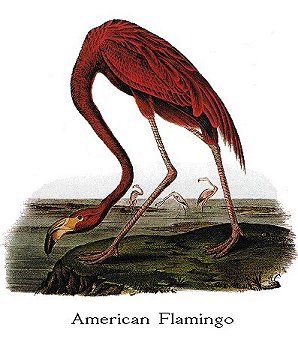

AMERICAN FLAMINGO. [Greater Flamingo.] |

| Genus | PHOENICOPTERUS RUBER, Linn. [Phoenicopterus ruber.] |

On the 7th of May, 1832, while sailing from Indian Key,

one of the numerous islets that skirt the south-eastern coast of the Peninsula of Florida, I for the

first time saw a flock of Flamingoes. It was on the afternoon of one of those

sultry days which, in that portion of the country, exhibit towards evening the

most glorious effulgence that can be conceived. The sun, now far advanced

toward the horizon, still shone with full splendour, the ocean around glittered

in its quiet beauty, and the light fleecy clouds that here and there spotted the

heavens, seemed flakes of snow margined with gold. Our bark was propelled

almost as if by magic, for scarcely was a ripple raised by her bows as we moved

in silence. Far away to seaward we spied a flock of Flamingoes advancing in

"Indian line," with well-spread wings, outstretched necks, and long legs

directed backwards. Ah! reader, could you but know the emotions that then

agitated my breast! I thought I had now reached the height of all my

expectations, for my voyage to the Floridas was undertaken in a great measure

for the purpose of studying these lovely birds in their own beautiful islands.

I followed them with my eyes, watching as it were every beat of their wings; and

as they were rapidly advancing towards us, Captain DAY, who was aware of my

anxiety to procure some, had every man stowed away out of sight and our gunners

in readiness. The pilot, Mr. EGAN, proposed to offer the first taste of his

"groceries" to the leader of the band. He was a first-rate shot, and had

already killed many Flamingoes. The birds were now, as I thought, within a

hundred and fifty yards; when suddenly, to our extreme disappointment, their

chief veered away, and was of course followed by the rest. Mr. EGAN, however,

assured us that they would fly round the Key, and alight not far from us, in

less than ten minutes, which in fact they did, although to me these minutes

seemed almost hours. "Now they come," said the pilot, "keep low." This we did;

but, alas! the Flamingoes were all, as I suppose, very old and experienced

birds, with the exception of one, for on turning round the lower end of the Key,

they spied our boat again, sailed away without flapping their wings, and

alighted about four hundred yards from us, and upwards of one hundred from the

shore, on a "soap flat" of vast extent, where neither boat nor man could

approach them. I however watched their motions until dusk, when we reluctantly

left the spot and advanced toward Indian Key. Mr. EGAN then told me that these

birds habitually returned to their feeding-grounds toward evening, that they fed

during the greater part of the night, and were much more nocturnal in their

habits than any of the Heron tribe.

When I reached Key West, my first inquiries, addressed to Dr. BENJAMIN

STROBEL, had reference to the Flamingoes, and I felt gratified by learning that

he had killed a good number of them, and that he would assist us in procuring

some. As on that Key they are fond of resorting to the shallow ponds formerly

kept there as reservoirs of water, for the purpose of making salt, we visited

them at different times, but always without success; and, although I saw a great

number of them in the course of my stay in that country, I cannot even at this

moment boast of having had the satisfaction of shooting a single individual.

A very few of these birds have been known to proceed eastward of the

Floridas beyond Charleston in South Carolina, and some have been procured there

within eight or ten years back. None have ever been observed about the mouths

of the Mississippi; and to my great surprise I did not meet with any in the

course of my voyage to the Texas, where, indeed, I was assured they had never

been seen, at least as far as Galveston Island. The western coast of Florida,

and some portions of that of Alabama, in the neighbourhood of Pensacola, are the

parts to which they mostly resort; but they are said to be there always

extremely shy, and can be procured only by waylaying them in the vicinity of

their feeding-grounds toward evening, when, on one occasion, Dr. STROBEL shot

several in the course of a few hours. Dr. LEITNER also procured some in the

course of his botanical excursions along the western coast of the Floridas,

where he was at last murdered by some party of Seminole Indians, at the time of

our last disastrous war with those children of the desert.

Flamingoes, as I am informed, are abundant on the Island of Cuba, more

especially on the southern side of some of its shores, and where many islets at

some distance from the mainland afford them ample protection. In their flight

they resemble Ibises, and they usually move in lines, with the neck and legs

fully extended, alternately flapping their wings for twenty or thirty yards and

sailing over a like space. Before alighting they generally sail round the place

for several minutes, when their glowing tints become most conspicuous. They

very rarely alight on the shore itself, unless, as I am told, during the

breeding season, but usually in the water, and on shallow banks, whether of mud

or of sand, from which, however, they often wade to the shores. Their walk is

stately and slow, and their cautiousness extreme, so that it is very difficult

to approach them, as their great height enables them to see and watch the

movements of their various enemies at a distance. When travelling over the

water, they rarely fly at a greater height than eight or ten feet; but when

passing over the land, no matter how short the distance may be, they, as well as

Ibises and Herons, advance at a considerable elevation. I well remember that on

one occasion, when near Key West, I saw one of them flying directly towards a

small hammock of mangroves, to which I was near, and towards which I made, in

full expectation of having a fine shot. When the bird came within a hundred and

twenty yards, it rose obliquely, and when directly over my head, was almost as

far off. I fired, but with no other effect than that of altering its course,

and inducing it to rise still higher. It continued to fly at this elevation

until nearly half a mile off, when it sailed downwards, and resumed its wonted

low flight.

Although my friends Dr. JOHN BACHMAN, Dr. WILSON, and WILLIAM KUNHARDT,

Esq. of Charleston, have been at considerable trouble in endeavouring to

procure accounts of the nidification of these birds and their habits during the

breeding season, and although they, as well as myself, have made many inquiries

by letter respecting them, of persons residing in Cuba, all that has been

transmitted to me has proved of little interest. I am not, however, the less

obliged by the kind intentions of these individuals, one of whom, A. MALLORY,

Esq., thus writes to Captain CROFT.

"Matanzas, April 20, 1837.

"Capt. CROFT,

"Dear Sir,--I have made inquiry of several of the fishermen, and

salt-rakers, who frequent the keys to the windward of this place, in regard to

the habits of the Flamingo, and have obtained the following information, which

will be found, I believe, pretty correct: 1st, They build upon nearly all the

Keys to the windward, the nearest of which is called Collocino Lignas. 2ndly,

It builds upon the ground. 3rdly, The nest is an irregular mass of earth dug in

the salt ponds, and entirely surrounded by water. It is scooped up from the

immediate vicinity to the height of two or three feet, and is of course hollow

at the top. There is no lining, nor any thing but the bare earth. 4thly, The

number of eggs is almost always two. When there is one, there has probably been

some accident. The time of incubation is not known. The egg is white, and near

the size of the Goose's egg. On scraping the shell, it has a bluish tinge.

5thly, The colour of the young is nearly white, and it does not attain the full

scarlet colour until two years old. 6thly, When the young first leave the nest,

they take to the water, and do not walk for about a fortnight, as their feet are

almost as tender as jelly. I do not think it easy to procure an entire nest;

but I am promised some of the eggs, this being the time to procure them.

"Very truly your obedient servant,

"A. MALLORY."

Another communication is as follows:

"The Flamingo is a kind of bird that lives in lagoons having a

communication with the sea. This bird makes its nest on the shore of the same

lagoon, with the mud which it heaps up to beyond the level of the water. Its

eggs are about the size of those of a Goose; it only lays two or three at a

time, which are hatched about the end of May. The young when they break the

shell have no feathers, only a kind of cottony down which covers them. They

immediately betake themselves to the water to harden their feet. They take from

two to three months before their feathers are long enough to enable them to fly.

The first year they are rose-coloured, and in the second they obtain their

natural colour, being all scarlet; half their bill is black, and the points of

the wings are all black; the eyes entirely blue. Its flesh is savoury, and its

tongue is pure fat. It is easily tamed, and feeds on rice, maize-meal, &c. Its

body is about a yard high, and the neck about half as much. The breadth of the

nest, with little difference, is that of the crown of a hat. The way in which

the female covers the eggs is by standing in the water on one foot and

supporting its body on the nest. This bird always rests in a lagoon, supporting

itself on one leg alternately; and it is to be observed that it always stands

with its front to the wind."

An egg, presented to me by Dr. BACHMAN, and of which two were found in the

nest, measures three inches and three-eighths in length, two inches and

one-eighth in breadth, and is thus of an elongated form. The shell is thick,

rather rough or granulated, and pure white externally, but of a bluish tint when

the surface is scraped off.

RED FLAMINGO, Phoenicopterus Tuber, Wils. Amer. Orn., vol. viii. p. 145.

PHOENICOPTERUS RUBER, Bonap. Syn., p. 348.

AMERICAN or RED FLAMINGO, Nutt. Man., vol. ii. p. 71.

AMERICAN FLAMINGO, Phoenicopterus ruber, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. v. p. 255.

Male, 45 1/2, 66.

Rather rare, and only during summer in the Florida Keys, and the western

coast of Florida. Accidental as far as South Carolina. Constantly resident in

Cuba.

Adult Male.

Bill more than double the length of the head, straight and higher than

broad for half its length, then deflected and tapering to an obtuse point.

Upper mandible with its dorsal line straight, convex at the curve, and again

straight nearly to the end, when it becomes convex at the tip; the ridge broad

and convex, on the deflected part expanded into a lanceolate plate, having a

shallow groove in the middle, and separated from the edges by a narrow groove;

its extremity narrow, and thin-edged, but obtuse, this part being analogous to

the unguis of Ducks and other birds of that tribe. Lower mandible narrower than

the upper at its base, but much broader in the rest of its extent; its angle

rather long, wide, and filled with bare skin; its dorsal line concave, but at

the tip convex, the ridge deeply depressed, there being a wide channel in its

place, the sides nearly erect and a little convex, with six ridges on each side

toward the tip. The edges of the upper mandible are furnished with about 150

oblique lamellae, of which the external part is perpendicular, tapering,

pointed, and tooth-like. The edge of the lower mandible is incurved in an

extraordinary degree, leaving a convex upper surface about 1/4 inch in breadth,

covered in its whole extent with transverse very delicate lamellae, with an

external series of larger lamellae. The whole surface of the bill is covered

with a thickened leathery skin, which becomes horny toward the end. The

nostrils are linear, direct, sub-basal, nearer the margin than the ridge,

operculate, 1 1/4 inches long.

Head small, ovate; neck extremely elongated, and very slender, body

slender. Legs extremely long; the bare part of the tibia 9 1/2 inches, with 30

very broad scutella before, and about 40 behind, the scutella both here and on

the tarsus almost meeting so as scarcely to leave any interspace. Tarsus

extremely long, slender, its anterior scutella 54, posterior 65. Hind toe very

small, with 3 large scutella, its claw oblong, depressed, obtuse; it is 5

twelfths of an inch shorter than the outer, which is also 5 twelfths shorter

than the middle toe. The webs are anteriorly emarginate and crenate; they are

very thick, rugous, and reticulated, especially on the sole; the lower surface

of the toes is tesselated with squarish, flattish, thickened scales, resembling

mosaic work, and the upper surface is covered with numerous broad, but short

scutella. The claws are oblong, obtuse, depressed, and very similar to those of

a monkey.

The space between the bill and the eye is bare. The plumage is generally

compact, the feathers rounded; those on the neck short. Wings long, very broad,

pointed; the first primary half a twelfth of an inch shorter than the second,

which is longest, and exceeds the third by one-twelfth; some of the inner

secondaries much elongated, tapering, and extending five or six inches beyond

the first primary when the whig is closed. Tail very short.

Bill black beyond the curve, then orange, and towards the base pure yellow,

of which colour also is the bare skin at its base. Iris blue. Feet

lake-colour. The plumage is of a very rich pure scarlet, excepting the ten

primaries, and twenty of the secondaries, which are black, the inner ten

elongated secondaries being scarlet.

Length to carpal joint 27 3/4 inches, to end of wing 44, to end of tail

45 1/2, to end of claws 62 1/2; extent of wings 66; bare part of tibia 9; tarsus

13 1/2; middle toe and claw 3 5/8; hind toe and claw 1/2; spread of foot from

outer to inner claw 5; wing from flexure 16; tail 6; circumference of body 24.

Weight 7 lbs. 8 oz.

The Female is similar to the male, but much smaller; its weight 6 lbs. 4

oz.

A male preserved in spirits. On the roof of the mouth is a large prominent

median ridge, which toward the end has two sharp edges; the sides concave and

covered with lamellae. The lower mandible is deeply and widely grooved, forming

a cavity 1 inch in depth at the curvature, the tip narrowed but obtuse, and with

a flattened broadly ovate surface above. The tongue, which lies in this deep

groove, by which it is confined so as to be capable of little motion, is a

fleshy, somewhat compressed, decurved body, 2 inches 2 twelfths long, measured

along its upper median line, having at its base on each side three series of

very pointed papillae, and on each side about 20 conical recurved, horny,

acuminate papillae, about inch in length; between which is a narrow median

groove. These papillae terminate at the curvature, beyond which is a lanceolate

flattened horny surface, with a thin elevated margin, the organ at that part

tapering to an obtuse point, horny on its lower surface. The nostrils are 1 1/4

inches long; the aperture of the ear very small, 2 1/2 twelfths in diameter,

that of the eye 4 1/2 twelfths. In this specimen the whole of the thoracic and

abdominal viscera have been removed.

The trachea, which is narrow, little flattened, and with its rings firm,

passes down in front of the vertebrae to the distance of 12 inches, and is then

deflected to the right side for 11 inches more. The diameter at the upper part

is 4 3/4 twelfths, and it gradually enlarges to 5 1/2 twelfths; at the lower

part of the neck its greatest breadth is 7 twelfths. It then passes over the

vertebrae, continuing of the same breadth, enters the thorax, contracts at its

lower part and is compressed, its diameter being 4 twelfths. The number of

rings is 330. The bronchi are wide, short, compressed, of about 15 half rings.

The aperture of the glottis is 6 twelfths long; at its anterior part is a

transverse series of 12 short papillae directed forward, and behind it are

numerous pointed papillae, of which the middle are largest. The muscles of the

upper larynx are two, one passing obliquely from the edge of the marginal

cartilage to the edge of the thyroid bone, for the purpose of opening the

aperture of the glottis; the other passing from the fore part of the edge of the

thyroid bone to the base of the cricoid and arytenoid, for the purpose of

pulling these parts forward, and thus closing the aperture. The contractor

muscles are of moderate strength, and the trachea is enveloped in numerous

layers of dense cellular tissue. The sterno-tracheals, which are of moderate

size, are in part a continuation of the contractors, which moreover send a slip

to the inferior larynx.

A female also preserved in spirits is much smaller. The oesophagus, Fig. 1, [a b c d] (diminished one-third) is 2 feet 1 inch long, only 3 twelfths in

width at the upper part, and diminishes to 2 1/2 twelfths. At the lower part of

the neck however it enlarges into a crop, [c d e], 3 1/4 inches long and 2 1/2

inches in its greatest width. On entering the thorax, the oesophagus has a diameter

of 9 twelfths; the proventriculus, Fig. 2, [a b c], enlarges to an ovate sac, 1 1/4 inches in its greatest breadth.

The stomach, [d e f], is a very muscular gizzard, of an elliptical form, placed obliquely,

and exactly resembling that of a Duck or Goose; its length 1 inch 7 twelfths, its breadth 2

inches 3 twelfths. Its lateral muscles are extremely developed, the left being

1 inch 1 twelfth thick, the other 1 inch; the epithelium thick, tough,

brownish-red, marked with longitudinal coarse grooves, but not flattened on the

two surfaces, opposite the muscles, as is the case in Ducks and Geese. The

proventricular glands are very large, and occupy a belt if inches in breadth.

The contents of the stomach are numerous very small univalve shells of a great

variety of species and fragments of larger shells, which, however, have probably

been used in place of gravel; for the structure of the OEsophagus and stomach

would indicate that the bird is graminivorous. The intestine, [f k], which is

very long, and of considerable width, its diameter being greater than that of

the upper part of the oesophagus, is very regularly and beautifully convoluted,

presenting, when the bird is opened in front, 10 parallel convolutions, [f g h i

j k], inclined from right to left at an angle of about 30 degrees. The

duodenum, [f g h], passes round the edge of the stomach, curves upwards as far

as the fore part of the proventiculus, is then doubled on itself, reaches the

right lobe of the liver, which has a large elliptical gall-bladder, and forms 32

half curves in all, ending above the stomach in the rectum. The intestine is 11

feet 4 inches long, its average diameter 4 1/2 twelfths. The rectum, Fig. 3, [a b], is 5 1/2 inches long, its diameter 1/2 inch. The coeca, [c d], are 4 inches long; for 1/2 inch at the base their diameter is 1 twelfth, immediately after 4

twelfths; they then taper to the extremity, which is obtuse. The cloaca is very

large and globular.

| Next >> |