| Family XXXIX. ANATINAE. DUCKS. GENUS IV. ANAS, Linn. DUCK. |

Next >> |

Family |

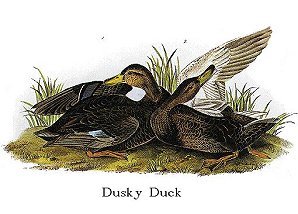

DUSKY DUCK. [American Black Duck.] |

| Genus | ANAS OBSCURA, Gmel. [Anas rubripes.] |

This species, which is known in all parts of the United States by the name of "Black Duck,"' extends its migrations from the Straits of Belle Isle, on the

coast of Labrador, to Texas. Straight as the fact may appear, it breeds in both

these countries, as well as in many of the intermediate districts. On the loth

of May, 1833, I found it breeding along the marshy edges of inland pools, near

the Bay of Fundy, and, on Whitehead Island in the same bay, saw several young

birds of the same species, which, although apparently not more than a week old,

were extremely active both on land and in the water. On the 30th of April,

1837, my son discovered a nest on Galveston Island, in Texas. It was formed of

grass and feathers, the eggs eight in number, lying on the former, surrounded

with the down and some feathers of the bird, to the height of about three

inches. The internal diameter of the nest was about six inches, and its walls

were nearly three in thickness. The female was sitting, but flew off in silence

as he approached. The situation selected was a clump of tall slender grass, on

a rather sandy ridge, more than a hundred yards from the nearest water, but

surrounded by partially dried salt-marshes. On the same island, in the course

of several successive days, we saw many of these Ducks, which, by their actions,

shewed that they also had nests. I may here state my belief, that the Gadwall,

Blue-wined Teal, Green-winged Teal, Mallard, American Widgeon, and Spoon-billed

Duck, all breed in that country, as I observed them there late in May, when they

were evidently paired. How far this fact may harmonize with the theories of

writers respecting the migration of birds in general, is more than I can at

present stop to consider. I have found the Black Duck breeding on lakes near

the Mississippi, as far up as its confluence with the Ohio, as well as in

Pennsylvania and New Jersey; and every one acquainted with its habits will tell

you, that it rears its young in all the Eastern States intervening between that

last mentioned and the St. Lawrence, and is of not less frequent occurrence

along the margins of all our great lakes. It is even found on the Columbia

river, and on the streams of the Rocky Mountains; but as Dr. RICHARDSON has not

mentioned his having observed it in Hudson's Bay or farther north, we may

suppose that it does not visit those countries.

On arriving in Labrador, on the 17th June, 1833, we found the Dusky Ducks

in the act of incubation, but for nearly a month after, met with no young birds,

which induced me to suppose that this species does not reach that country at so

early a period as many others, but lingers behind so as to be nearly four weeks

later than some of them. At the end of four weeks after our arrival, all the

females we met with had young broods, which they led about the fresh-water

ponds, and along their margins, either in search of food, or to secure them from

danger. None of these broods exceeded seven or eight in number, and, at this

early period of their life, we found them covered with long soft down of a deep

brown colour. When alarmed they would dive with great celerity several times in

succession, but soon became fatigued, made for the shore, ran a few feet from

the water, and squatted among the grass, where they were easily caught either by

some of our party, or by the Gulls, which are constantly on the look-out for

such dainty food. At other times, as soon as the mother apprehends danger, she

calls her young around her, when the little things form themselves into a line

in her wake, and carefully follow her in all her movements. If a Hawk or a Gull

make a plunge towards them she utters a loud cry of alarm, and then runs as it

were along the surface of the water, when the young dive as quick as lightning,

and do not rise again until they find themselves among the weeds or the rocks

along the shores. When they thus dive, they separate and pursue different

directions, and on reaching the land lie close among the herbage until assured,

by the well-known voice of their parent, that the danger is over. If they have

often been disturbed in one pond, their anxious mother leads them overland to

another; but she never, I believe, conducts them to the open sea until they are

able to fly. The young grow with remarkable rapidity, for, by the middle of

August, they almost equal their parents in size; and their apprehension of

danger keeps pace with their growth, for at the period of their southward

migration, which takes place in the beginning of September, they are as wild and

as cunning as the oldest and most experienced of their species. Each brood

migrates separately; and the old males, which abandoned the females when

incubation commenced, set out in groups of eight or ten. Indeed, it is not

common to see birds of this species assemble in such flocks as their relatives

the Mallards, although they at times associate with almost all the fresh-water

Ducks.

The males, on leaving the females, join together in small bands, and retire

into the interior of the marshes, where they remain until their moult is

completed. My young friend COOLEDGE brought me a pair shot on the 4th of July,

in Labrador, in so ragged a state that very few feathers remained even on the

whigs. On his approaching them, they skimmed over the surface of the water with

such rapidity, that when shot at they seemed as if flying away. On examining

these individuals I found them to be sterile, and I am of opinion that those

which are prolific moult at a later period, nature thus giving more protracted

vigour to those which have charge of a young brood. I think, reader, you will

be of the same opinion, when I have told you, that on the 5th of July I found

some which had young, and which were still in full plumage, and others, that

were broodless, almost destitute of feathers.

As many of the nests found in Labrador differed from the one mentioned

above, I will give you an account of them. In several instances, we found them

imbedded in the deep moss, at the distance of a few feet or yards from the

water. They were composed of a great quantity of dry grass and other vegetable

substances; and the eggs were always placed directly on this bed without the

intervention of the down and feathers, which, however, surrounded them, and

which, as I observed, the bird always uses to cover them when she is about to

leave the nest for a time. Should she be deprived of her eggs, she goes in

search of a male, and lays another set; but unless a robbery of this kinds

happens, she raises only a single brood in the season. But although this is the

case in Labrador, I was assured that this species rears two broods yearly in

Texas, although, having been but a short time in that country, I cannot vouch

for the truth of this assertion. The eggs are two inches and a quarter in

length, one inch and five-eighths in breadth, shaped like those of the domestic

fowl, with a smooth surface, and of a uniform yellowish-white colour, like that

of ivory tarnished by long exposure. The young, like those of the Mallard,

acquire the full beauty of their spring plumage before the season of

reproduction commences, but exhibit none of the curious changes which that

species undergoes.

Although the Dusky Duck is often seen on salt-water bays or inlets, it

resembles the Mallard in its habits, being fond of swampy marshes, rice-fields,

and the shady margins of our rivers, during the whole of its stay in such

portions of the Southern States as it is known to breed in. They are equally

voracious, and may sometimes be seen with their crops so protruded as to destroy

the natural elegance of their form. They devour, with the greatest eagerness,

water-lizards, young frogs and toads, tadpoles, all sorts of insects, acorns,

beech-nuts, and every kind of grain that they can obtain. They also, at times,

seize on small quadrupeds, gobble up earth-worms and leeches, and when in

salt-water, feed on shell-fish. When on the water, they often procure their

food by immersing their head and neck, and, like the Mallard, sift the produce

of muddy pools. Like that species also, they will descend in a spiral manner

from on high, to alight under an oak or a beech, when they have discovered the

mast to be abundant.

Shy and vigilant, they are with difficulty approached by the gunner, unless

under cover or on horseback, or in what sportsmen call floats, or shallow boats

made for the purpose of procuring water-fowl. They are, however, easily caught

in traps set on the margins of the waters to which they resort, and baited with

Indian corn, rice, or other grain. They may also be enticed to wheel round, and

even alight, by imitating their notes, which, in both sexes, seem to me almost

precisely to resemble those of the Mallard. From that species, indeed, they

scarcely differ in external form, excepting in wanting the curiously recurved

feathers of the tail, which Nature, as if clearly to distinguish the two

species, had purposely omitted in them.

The flight of this Duck, which, in as far as I know, is peculiar to

America, is powerful, rapid, and as sustained as that of the Mallard. While

travelling by day they may be distinguished from that species by the whiteness

of their lower wing-coverts, which form a strong contrast to the deep tints of

the rest of their plumage, and which I have attempted to represent in the figure

of the female bird in my plate. Their progress through the air, when at full

speed, must, I think, be at the rate of more than a mile in a minute, or about

seventy miles in an hour. When about to alight, they descend with double

rapidity, causing a strong rustling sound by the weight of their compact body

and the rapid movements of their pointed wings. When alarmed by a shot or

otherwise, they rise off their feet by a single powerful spring, fly directly

upwards for eight or ten yards, and then proceed in a straight line. Now, if

you are an expert band, is the moment to touch your trigger, and if you delay,

be sure your shot will fall short.

As it is attached to particular feeding grounds, and returns to them until

greatly molested, you may, by secreting yourself within shooting distance,

anticipate a good result; for even although shot it, it will reappear several

times in succession in the course of a few hours, unless it has been wounded.

The gunners in the vicinity of Boston, in Massachusetts, who kill great numbers

of these birds, on account of the high price obtained for them in the fine

market of that beautiful and hospitable city, procure them in the following

manner:--They keep live decoy Ducks of the Mallard kind, which they take with

them in their floats or boats. On arriving at a place which they know to be

suitable, they push or haul their boat into some small nook, and conceal it

among the grass or rushes. Then they place their decays, one in front of their

ambush, the rest on either side, each having a line attached to one of its feet,

with a stone at the other end, by which it is kept as if riding at anchor. One

of the birds is retained in the boat, where the gunner lies concealed, and in

cold weather amply covered with thick and heavy clothing. No sooner is all in

order, than the decoy Ducks, should some wild birds appear, sound their loud

call-notes, anxious as they feel to be delivered from their sad bondage. Should

this fail to produce the desired effect of drawing the Wild Ducks near, the poor

bird in the boat is pinched on the rump, when it immediately calls aloud; those

at anchor respond, and the joint clamour attracts the travellers, who now cheek

their onward speed, wheel several times over the spot, and at last alight. The

gunner seldom waits long for a shot, and often kills fifteen or twenty of the

Black Ducks at a single discharge of his huge piece, which is not unfrequently

charred with as much as a quarter of a pound of powder and three quarters of a

pound of shot!

The Black Ducks generally appear in the sound of Long Island in September

or October, but in very cold weather proceed southward; while those which breed

in Texas, as I have been informed, remain there all the year. At their first

arrival they betake themselves to the fresh-water ponds, and soon become fat,

when they afford excellent eating; but when the ponds are covered with ice, and

they are forced to betake themselves to estuaries or inlets of the sea, their

flesh becomes less juicy and assumes a fishy flavour. During continued frost

they collect into larger bodies than at any other time, a flock once alighted

seeming to attract others, until at last hundreds of them meet, especially in

the dawn and towards sunset. The larger the flock however, the more difficult

it is to approach it, for many sentinels are seen on the look-out, while the

rest are asleep or feeding along the shores. Unlike the "Sea Ducks," this

species does not ride at anchor, as it were, during its hours of repose.

My friend, the Reverend Dr. JOHN BACHMAN, assures me that this bird, which

some years ago was rather scarce in South Carolina, is now becoming quite

abundant in that state, where, during autumn and winter, it resorts to the

rice-fields. After feeding a few weeks on the seeds it becomes fat, juicy, and

tender. He adds that the farther inland, the more plentifully does it occur,

which may be owing to the many steamers that ply on the rivers along the sea

coast, where very few are to be seen. They are, however, followed in their

retreats, and shot in great numbers, so that the markets of Charleston are now

amply supplied with them. He also informs me that be has known hybrid broods

produced by a male of this species and the common domestic Duck; and that he had

three of these hybrid females, the eggs of all of which were productive. The

young birds were larger than either of their parents, but although they laid

eggs in the course of the following spring, not one of these proved impregnated.

He further states that he procured three nests of the Dusky Duck in the State of

New York.

The young of this species, in the early part of autumn, afford delicious

eating, and, in my estimation, are much superior in this respect to the more

celebrated Canvass-back Duck. That the species should not before now have been

brought into a state of perfect domestication, only indicates our reluctance

unnecessarily to augment the comforts which have been so bountifully accorded by

Nature to the inhabitants of our happy country. In our eastern markets the

price of these birds is from a dollar to a dollar and fifty cents the pair.

They are dearer at New Orleans, but much cheaper in the States of Ohio and

Kentucky, where they are still more abundant. Their feathers are elastic, and

as valuable as those of any other species.

I have represented a pair of these birds procured in the full perfection of

their plumage.

DUSKY DUCK, Anas obscura, Wils. Amer. Orn., vol. viii. p. 141.

ANAS OBSCURA, Bonap. Syn., p. 384.

DUSKY DUCK, Anas obscure, Nutt. Man., vol. ii. p. 392.

DUSKY DUCK, Anas obscure, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. iv. p. 15.

Male, 24 1/2, 38 1/2. Female, 22, 34 1/4.

Breeds in Texas, westward, and throughout the United States, British

Provinces, and Labrador. Columbia river. Common in autumn and spring along the

Middle Atlantic Districts. Abundant in the Southern and Western States in

winter.

Adult Male.

Bill about the length of the head, higher than broad at the base, depressed

and widened towards the end, rounded at the tip. Upper mandible with the dorsal

line sloping and a little concave, the ridge at the base broad and flat, towards

the end broadly convex, as are the sides, the edges soft and thin, the marginal

lamellae about forty on each side; the unguis obovate, curved, abrupt at the

end. Nasal groove elliptical, sub-basal, filled by the soft membrane of the

bill; nostrils sub-basal, placed near the ridge, longitudinal, elliptical,

pervious. Lower mandible slightly curved upwards, flattened, with the angle

very long, narrow, and rather pointed, the lamellae about sixty.

Head of moderate size, oblong, compressed; neck rather long and slender;

body full, depressed. Feet short, stout, placed a little behind the centre of

the body; legs bare a little above the joint; tarsus short, a little compressed,

anteriorly with small scutella, externally of which is a series continuous with

those of the other toe, laterally and behind with reticulated angular scales.

Hind toe extremely small, with a very narrow membrane; third toe longest, fourth

a little shorter, but longer than the second; the scutella of the second and

third oblique, of the outer transverse; the three anterior toes connected by

reticulated membranes, the outer with a thick margin, the inner with the margin

extended into a slightly lobed web. Claws small, arched, compressed, rather

obtuse, that of the middle toe much larger, with a dilated, thin edge.

Plumage dense, soft, and elastic; on the head and neck the feathers

linear-oblong, on the other parts in general broad and rounded. Wings of

moderate breadth and length, acute; primaries narrow and tapering, the second

longest, the first very little shorter; secondaries broad, curved inwards, the

inner elongated and tapering. Tail short, much rounded, of eighteen acute

feathers, none of which are recurved.

Bill yellowish-green, the unguis dusky. Iris dark brown. Feet orange-red,

the webs dusky. The upper part of the head is glossy brownish-black, the

feathers margined with light brown; the sides of the head and a band over the

eye are light greyish-brown, with longitudinal dusky streaks; the middle of the

neck is similar, but more dusky. The general colour is blackish-brown, a little

paler beneath, all the feathers margined with pale reddish-brown. The

wing-coverts are greyish-dusky, with a faint tine of green; the ends of the

secondary coverts velvet-black. Primaries and their coverts blackish-brown,

with the shafts brown; secondaries darker; the speculum is green, blue, violet,

or amethyst purple, according to the light in which it is viewed, bounded by

velvet-black, the feathers also tipped with a narrow line of white. The whole

under surface of the wing and the axillaries, white.

Length to end of tail 24 1/2 inches, to end of claws 26; extent of wings

38 1/2; bill 2 4/12 along the back; wing from flexure 11 1/2; tail 4 4/12;

tarsus 1 (6 1/2)/12; middle toe 2 3/12, its claw 4/12; first toe 5/12, its

claw 2/12. Weight 3 lbs.

Adult Female.

The female, which is somewhat smaller, resembles the male in colour, but is

more brown, and has the speculum of the same tints, but without the white

terminal line.

Length to end of tail 22 inches, to end of wings 21 1/4, to end of claws

22; wing from flexure 10 1/2; extent of wings 34 1/4; tarsus 2, middle toe and

claw 2 1/2; hind toe and claw 5/12.

In this species, the number of feathers in the tail is eighteen, although

it has been represented as sixteen. In form and proportions the Dusky Duck is

very closely allied to the Mallard. The following account of the digestive and

respiratory organs is obtained from the examination of an adult male.

On the upper mandible are 43 lamellae; on the lower, 85 in the upper, and

56 in the lower series. The tongue is 1 1/12 inches long, with the sides

parallel and furnished with a double row of filaments, numerous small conical

papillae at the base, a median groove on the Lipper surface, and a thin rounded

appendage, a twelfth and a half in length at the tip. The aperture of the

glottis is 7 (1/2)/12 long, with very numerous minute papillae behind. The

OEsophagus 12 inches long, of a uniform diameter of 4/12, until near the lower

part of the neck, where it enlarges to 8/12, again contracts as it enters the

thorax ending in the proventriculus, which is 1 1/4 long, with numerous oblong

glandules, about a twelfth in length. Gizzard obliquely elliptical, 2 1/4

inches across, 1 8/12 in length, its lateral muscles extremely large, the left

10/12 thickness the right 9/12; their tendons large and strong; the lower muscle

moderately thick; the cuticular lining firm and rugous, the grinding surfaces

nearly smooth. The intestine, which is 5 feet 7 1/2 inches long, is slender and

nearly uniform in diameter, measuring 4/12 across in the duodenal portion, 3/12

in the rest of its extent; the rectum 3 1/2 inches long, dilated into a globular

cloaca 1 inch in length, and of nearly the same diameter. The coeca are 6 1/4

long, (1 1/2)/12 in diameter for 2 inches of their length, enlarged to 3/12 in

the rest of their extent, and terminating in all obtuse extremity.

The trachea, moderately extended, is 10 inches long. Its lateral or

contractor muscles are strong, and it is furnished with a pair of

cleido-tracheals, and a pair of sterno-tracheals. The number of rings is 136,

besides 12 united rings forming a large inferior larynx, which has a

transversely oblong bony expansion, forming on the left side a bulging and

rounded sac. There are 28 bronchial half rings on the right side, 26 on the

left.

| Next >> |