|

Family III. STRIGINAE. OWLS.

GENUS III. STRIX, Linn. SCREECH-OWL . |

Next >> |

Family |

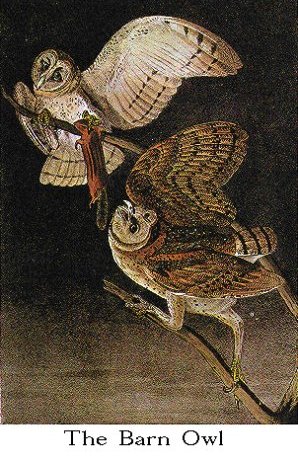

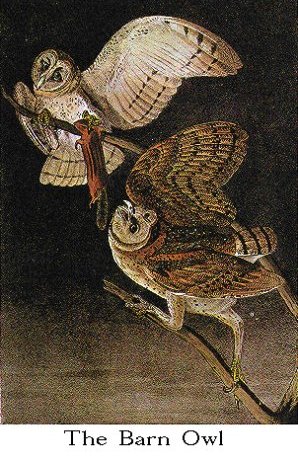

THE BARN OWL. [Common Barn-Owl.] |

| Genus | STRIX AMERICANA, Aud.

[Tyto alba.] |

The Barn Owl of the United States is far more abundant in the Southern Districts than in the other parts. I never found it to the east of

Pennsylvania, and only twice in that State, nor did I ever see, or even hear of

one in the Western Country; but as soon as I have reached the maritime districts

of the Carolinas, Georgia, the Floridas, and all along to Louisiana, the case

has always been different. In Cuba they are quite abundant, according to the

reports which I have received from that island. During my visit to Labrador I

neither saw any of these birds, nor found a single person who had ever seen

them, although the people to whom I spoke were well acquainted with the Snowy

Owl, the Grey Owl, and the Hawk Owl.

THOMAS BUTLER KING, Esq., of St. Simon's Island, Georgia, sent me two very

beautiful specimens of this Owl, which had been caught alive. One died shortly

after their arrival at Charleston; the other was in fine order when I received

it. The person to whose care they were consigned, kept them for many weeks at

Charleston before I reached that city, and told me that in the night their cries

never failed to attract others of the same species, which he observed hovering

about the place of their confinement.

This species is altogether nocturnal or crepuscular, and when disturbed

during the day, flies in an irregular bewildered manner, as if at a loss how to

look for a place of refuge. After long observation, I am satisfied that our

bird feeds entirely on the smaller species of quadrupeds, for I have never found

any portions of birds about their nests, nor even the remains of a single

feather in the pellets which they regurgitate, and which are always formed of

the bones and hair of quadrupeds.

Owls which approach to the diurnal species in their habits, or which hunt

for food in the morning and evening twilight, are apt to seize on objects which

are themselves more diurnal than those which I have found to form the constant

food of our Barn Owl. Thus the Short-eared, the Hawk, the Fork-tailed, the

Burrowing, and other Owls, which hunt either during broad day, towards evening,

or at the return of day, will be found to feed more on diurnal animals than the

present species. I have no doubt that the anatomist will detect corresponding

differences in the eye, as they have already been found in the ear. The stomach

is elongated, almost smooth, and of a deep gamboge-yellow; the intestines small,

rather tough, and measuring one foot nine inches in length.

The flight of the Barn Owl is light, regular, and much protracted. It

passes through the air at an elevation of thirty or forty feet, in perfect

silence, and pounces on its prey like a Hawk, often waiting for a fair

opportunity from the branch of a tree, on which it alights for the purpose.

During day they are never seen, unless accidentally disturbed, when they

immediately try to hide themselves. I am not aware of their having any

propensity to fish, as the Snowy Owl has, nor have I ever seen one pursuing a

bird. Ever careful of themselves, they retreat to the hollows of trees and such

holes as they find about old buildings. When kept in confinement they feed

freely on any kind of flesh, and will stand for hours in the same position,

frequently resting on one leg, while the other is drawn close to the body. In

this position I watched one on my drawing table for six hours.

This species is never found in the depth of the forest, but confines itself

to the borders of the woods around large savannas or old abandoned fields

overgrown with briars and rank grass, where its food, which consists principally

of field-mice, moles, rats, and other small quadrupeds, is found in abundance,

and where large beetles and bats fly in the morning and evening twilight. It

seldom occurs at a great distance from the sea. I am not aware that it ever

emits any cry or note, as other Owls are wont to do; but it produces a hollow

hissing sound, continued for minutes at a time, which has always reminded me of

that given out by an opossum when about to die by strangulation.

When on the round, this Owl moves by sidelong leaps, with the body much

inclined downwards. If wounded in the wing, it yet frequently escapes through

the celerity of its motions. Its hearing is extremely acute, and as it marks

your approach, instead of throwing itself into an attitude of defence, as Hawks

are wont to do, it instantly swells out its plumage, extends its wings and tail,

hisses, and clacks its mandibles with force and rapidity. If seized in the

hand, it bites and scratches, inflicting deep wounds with its bill and claws.

It is by no means correct to say that this Owl, or indeed any other, always

swallows its prey entire: some which I have kept in confinement, have been seen

tearing a young bare in pieces with their bills in the manner of Hawks; and

mice, small rats, or bats, are the largest objects that I have seen them gobble

up entire, and not always without difficulty. From having often observed their

feet and legs covered with fresh earth, I am inclined to think that they may use

them to scratch mice or moles out of their shallow burrows, a circumstance which

connects them with the Burrowing Owls of our western plains, which like them

have very long legs. In a room their flight is so noiseless that one is

surprised to find them removed from one place to another without having heard

the least sound. They disgorge their pellets with difficulty, although

generally at a single effort, but I did not observe that this action was

performed at any regular period. The examination of entire specimens has

brought to light a remarkable and unvarying character in the feathers which

fringe the operculum. In both the American and European species the tubes of

these feathers are very large; but in the American bird the shafts are obsolete,

whereas in the European bird, each tube bears a very slender shaft, about half

an inch long, and furnished with about a dozen filaments on each side, forming

an elliptical or obovate feather. This character and the great difference in

size, will suffice to distinguish the American bird, to which, it having been

shewn to be distinct, in my Ornithological Biography, I have given the name of

Strix Americana.

WHITE or BARN OWL, Strix flammea, Wils. Amer. Orn., vol. vi. p. 57.

STRIX FLAMMEA, Bonap. Syn., p. 38.

WHITE or BARN OWL, Strix flammea, Nutt. Man., vol. i. p. 139.

BARN OWL, Strix flammea, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. ii. p. 403;

vol. v. p. 388.

Feathers margining the operculum with the shaft and webs undeveloped. Bill

pale greyish-yellow; claws and scales brownish-yellow. General colour of upper

parts greyish-brown, with light yellowish-red interspersed, produced by very

minute mottling; each feather having toward the end a central streak of deep

brown, terminated by a small oblong greyish-white spot; wings similarly

coloured; secondary coverts and outer edges of primary coverts with a large

proportion of light brownish-red; quills and tail transversely barred with

brown; lower parts pale brownish-red, fading anteriorly into white, each feather

having a small dark brown spot at the tip.

Closely allied to Strix flammea, but larger, and differing somewhat in

colour, being generally darker, with the ruff red. A character by which they

may always be distinguished is found in the operculum, the feathers margining

which are in the present species reduced to their tubes, the shafts and

filaments being wanting, whereas in the European species each tube bears a very

slender shaft, about half an inch long, and furnished with about half a dozen

filaments on each side.

Male, 17, 42. Female, 18, 46.

| Next >> |