| Family XLII. LARINAE. GULLS. GENUS I. RHYNCHOPS, Linn. SKIMMER. |

Next >> |

Family |

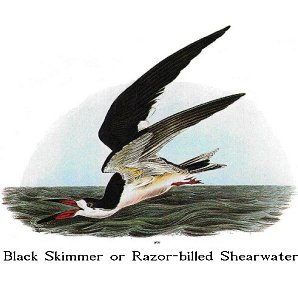

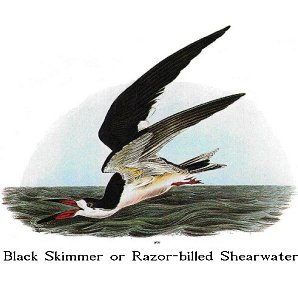

BLACK SKIMMER OR RAZOR-BILLED SHEARWATER. [Black Skimmer.] |

| Genus | RHYNCHOPS NIGRA, Linn. [Rynchops niger.] |

This bird, one of the most singularly endowed by nature, is a constant

resident on all the sandy and marshy shores of our more southern States, from

South Carolina to the Sabine river, and doubtless also in Texas, where I found

it quite abundant in the beginning of spring. At this season parties of Black

Skimmers extend their movements eastward as far as the sands of Long Island,

beyond which however I have not seen them. Indeed in Massachusetts and Maine

this bird is known only to such navigators as have observed it in the southern

and tropical regions.

To study its habits therefore, the naturalist must seek the extensive

sand-bars, estuaries, and mouths of the rivers of our Southern States, and enter

the sinuous bayous intersecting the broad marshes along their coasts. There,

during the warm sunshine of the winter days, you will see thousands of Skimmers,

covered as it were with their gloomy mantles, peaceably lying beside each other,

and so crowded together as to present to your eye the appearance of an immense

black pall accidentally spread on the sand. Such times are their hours of rest,

and I believe of sleep, as, although partially diurnal, and perfectly able to

discern danger by day, they rarely feed then, unless the weather be cloudy. On

the same sands, yet apart from them, equal numbers of our Black-headed Gulls may

be seen enjoying the same comfort in security. Indeed the Skimmers are rarely

at such times found on sand or gravel banks which are not separated from the

neighbouring shores by some broad and deep piece of water. I think I can safely

venture to say that in such places, and at the periods mentioned, I have seen

not fewer than ten thousand of these birds in a single flock. Should you now

attempt to approach them, you will find that as soon as you have reached within

twice the range of your long duck-gun, the crowded Skimmers simultaneously rise

on their feet, and watch all your movements. If you advance nearer, the whole

flock suddenly taking to wing, fill the air with their harsh cries, and soon

reaching a considerable height, range widely around, until, your patience being

exhausted, you abandon the place. When thus taking to wing in countless

multitudes, the snowy white of their under parts gladdens your eye, but anon,

when they all veer through the air, the black of their long wings and upper

parts produces a remarkable contrast to the blue sky above. Their aerial

evolutions on such occasions are peculiar and pleasing, as they at times appear

to be intent on removing to a great distance, then suddenly round to, and once

more pass almost over you, flying so close together as to appear like a black

cloud, first ascending, and then rushing down like a torrent. Should they see

that you are retiring, they wheel a few times close over the ground, and when

assured that there is no longer any danger, they alight pell-mell, with wings

extended upwards, but presently closed, and once more huddling together they lie

down on the ground, to remain until forced off by the tide. When the Skimmers

repose on the shores of the mainland during high-water, they seldom continue

long on the same spot, as if they felt doubtful of security; and a person

watching them at such times might suppose that they were engaged in searching

for food.

No sooner has the dusk of evening arrived than the Skimmers begin to

disperse, rise from their place of rest singly, in pairs, or in parties from

three or four to eight or ten, apparently according to the degree of hunger they

feel, and proceed in different directions along parts of the shores previously

known to them, sometimes going up tide-rivers to a considerable distance. They

spend the whole night on wing, searching diligently for food. Of this I had

ample and satisfactory proof when ascending the St. John river in East Florida,

in the United States schooner Spark. The hoarse cries of the Skimmers never

ceased more than an hour, so that I could easily know whether they were passing

upwards or downwards in the dark. And this happened too when I was at least a

hundred miles from the mouth of the river.

Being aware, previously to my several visits to the peninsula of the

Floridas and other parts of our southern coasts where the Razor-bills are

abundant, of the observations made on this species by M. LESSON, I paid all

imaginable attention to them, always aided with an excellent glass, in order to

find whether or not they fed on bivalve shell-fish found in the shallows of

sand-bars and other places at low water; but not in one single instance did I

see any such occurrence, and in regard to this matter I agree with WILSON in

asserting that, while with us, these birds do not feed on shell-fish. M.

LESSON's words are as follows:--"Quoique le Bec-en-ciseaux semble defavorise par

la forme de son bec, nous acquimes la preuve qu'il savait s'en servir avec

avantage et avec la plus grande adresse. Les plages sabloneuses de Peuce sont

en effect remplies de Mactres, coquilles bivalves, que la maree descendente

laisse presque a sec dans des petites mares; le Bec-en-ciseaux tres au fait de

cet phenomene, se place aupres de ces mollusques, attend que leur valves

s'entrouvrent un peu, et profile aussitot de ce movement en enforcant la lame

inferieure et tranchante de son bec entre les valves qui se reserrent.

L'oiseaux enleve alors la coquille, la frappe sur la greve, coupe le ligament du

mollusque, et peut ensuite avaler celui-ci sans obstacle. Plusieurs fois nous

avons ete temoins de cet instinct tres perfectionne."

While watching the movements of the Black Skimmer as it was searching for

food, sometimes a full hour before it was dark, I have seen it pass its lower

mandible at an angle of about 45 degrees into the water, whilst its moveable

upper mandible was elevated a little above the surface. In this manner, with

wings raised and extended, it ploughed as it were, the element in which its

quarry lay to the extent of several yards at a time, rising and falling

alternately, and that as frequently as it thought it necessary for securing its

food when in sight of it; for I am certain that these birds never immerse their

lower mandible until they have observed the object of their pursuit, for which

reason their eyes are constantly directed downwards like those of Terns and

Gannets. I have at times stood nearly an hour by the side of a small pond of

salt water having a communication with the sea or a bay, while these birds would

pass within a very few yards of me, then apparently quite regardless of my

presence, and proceed fishing in the manner above described. Although silent at

the commencement of their pursuit, they become noisy as the darkness draws on,

and then give out their usual call notes, which resemble the syllables hurk,

hurk, twice or thrice repeated at short intervals, as if to induce some of their

companions to follow in their wake. I have seen a few of these birds glide in

this manner in search of prey over a long salt-marsh bayou, or inlet, following

the whole of its sinuosities, now and then lower themselves to the water, pass

their bill along the surface, and on seizing a prawn or a small fish, instantly

rise, munch and swallow it on wing. While at Galveston Island, and in the

company of my generous friend EDWARD HARRIS and my son, I observed three Black

Skimmers, which having noticed a Night Heron passing over them, at once rose in

the air, gave chase to it, and continued their pursuit for several hundred

yards, as if intent on overtaking it. Their cries during this chase differed

from their usual notes, and resembled the barkings of a very small dog.

The flight of the Black Skimmer is perhaps more elegant than that of any

water bird with which I am acquainted. The great length of its narrow wings,

its partially elongated forked tail, its thin body and extremely compressed

bill, all appear contrived to assure it that buoyancy of motion which one cannot

but admire when he sees it on wing. It is able to maintain itself against the

heaviest gale; and I believe no instance has been recorded of any bird of this

species having been forced inland by the most violent storm. But, to observe

the aerial movements of the Skimmer to the best advantage, you must visit its

haunts in the love season. Several males, excited by the ardour of their

desires, are seen pursuing a yet unmated female. The coy one, shooting aslant

to either side, dashes along with marvellous speed, flying hither and thither,

upwards, downwards, in all directions. Her suitors strive to overtake her; they

emit their love-cries with vehemence; you are gladdened by their softly and

tenderly enunciated ha, ha, or the hack, hack, cae, cae, of the last in the

chase. Like the female they all perform the most curious zigzags, as they

follow in close pursuit, and as each beau at length passes her in succession, he

extends his wings for an instant, and in a manner struts by her side. Sometimes

a flock is seen to leave a sand-bar, and fly off in a direct course, each

individual apparently intent on distancing his companions; and then their

mingling cries of ha, ha, hack, hack, cae, cae, fill the air. I once saw one of

these birds fly round a whole flock that had alighted, keeping at the height of

about twenty yards, but now and then tumbling as if its wings had suddenly

failed, and again almost upsetting, in the manner of the Tumbler Pigeon.

On the 5th of May, 1837, I was much surprised to find a large flock of

Skimmers alighted and apparently asleep, on a dry grassy part of the interior of

Galveston Island in Texas, while I was watching some Marsh Hawks that were

breeding in the neighbourhood. On returning to the shore, however, I found that

the tide was much higher than usual, in consequence of a recent severe gale, and

had covered all the sand banks on which I had at other times observed them

resting by day.

The instinct or sagacity which enables the Razor-bills, after being

scattered in all directions in quest of food during a long night, often at great

distances from each other, to congregate again towards morning, previously to

their alighting on a spot to rest, has appeared to me truly wonderful; and I

have been tempted to believe that the place of rendezvous had been agreed upon

the evening before. They have a great enmity towards Crows and Turkey Buzzards

when at their breeding ground, and on the first appearance of these marauders,

some dozens of Skimmers at once give chase to them, rarely desisting until quite

out of sight.

Although parties of these birds remove from the south to betake themselves

to the eastern shores, and breed there, they seldom arrive at Great Egg Harbour

before the middle of May, or deposit their eggs until a month after, or about

the period when, in the Floridas and on the coast of Georgia and South Carolina,

the young are hatched. To these latter sections of the country we will return,

reader, to observe their actions at this interesting period. I will present you

with a statement by my friend the Rev. JOHN BACHMAN, which he has inserted in my

journal. "These birds are very abundant, and breed in great numbers on the sea

islands at Bull's Bay. Probably twenty thousand nests were seen at a time. The

sailors collected an enormous number of their eggs. The birds screamed all the

while, and whenever a Pelican or Turkey Buzzard passed near, they assailed it by

hundreds, pouncing on the back of the latter, that came to rob them of their

eggs, and pursued them fairly out of sight. They had laid on the dry sand, and

the following morning we observed many fresh-laid eggs, when some had been

removed the previous afternoon." Then, reader, judge of the deafening angry

cries of such a multitude, and see them all over your head begging for mercy as

it were, and earnestly urging you and your cruel sailors to retire and leave

them in the peaceful charge of their young, or to settle on their lovely rounded

eggs, should it rain or feel chilly.

The Skimmer forms no other nest than a slight hollow in the sand. The

eggs, I believe, are always three, and measure an inch and three quarters in

length, an inch and three-eighths in breadth. As if to be assimilated to the

colours of the birds themselves, they have a pure white ground, largely patched

or blotched with black or very dark umber, with here and there a large spot of a

light purplish tint. They are as good to eat as those of most Gulls, but

inferior to the eggs of Plovers and other birds of that tribe. The young are

clumsy, much of the same colour as the sand on which they lie, and are not able

to fly until about six weeks, when you now perceive their resemblance to their

parents. They are fed at first by the regurgitation of the finely macerated

contents of the gullets of the old birds, and ultimately pick up the shrimps,

prawns, small crabs, and fishes dropped before them. As soon as they are able

to walk about, they cluster together in the manner of the young of the Common

Gannet, and it is really marvellous how the parents can distinguish them

individually on such occasions. This bird walks in the manner of the Terns,

with short steps, and the tail slightly elevated. When gorged and fatigued,

both old and young birds are wont to lie flat on the sand, and extend their

bills before them; and when thus reposing in fancied security, may sometimes be

slaughtered in great numbers by the single discharge of a gun. When shot at

while on wing, and brought to the water, they merely float, and are easily

secured. If the sportsman is desirous of obtaining more, he may easily do so,

as others pass in full clamour close over the wounded bird.

BLACK SKIMMER or SHEAR-WATER, Rhynchops nigra, Wils. Amer. Orn.,vol. vii. p. 85.

RHINCOPS NIGRA, Bonap. Syn., p. 352.

BLACK SKIMMER, Nutt. Man., vol. ii. p. 264.

BLACK SKIMMER or RAZOR-BILLED SHEAR-WATER, Rhynchops nigra, Aud. Orn.

Biog., vol. iv. p. 203.

Male, 20, 48. Female, 16 3/4, 44 1/2.

During winter, in vast multitudes on the coast of Florida. In summer

dispersed in large flocks from Texas to New Jersey, breeding on sand beaches or

islands. In the evenings and at night ascends streams sometimes to the distance

of one hundred miles.

Adult Male.

Bill longer than the head, nearly straight, tetragonal at the base,

suddenly extremely compressed, and continuing so to the end. Upper mandible

much shorter than the lower, its dorsal outline very slightly convex, its ride

sharp, the sides erect, more or less convex, the edges approximated so as to

leave merely a very narrow groove between them; the tip a little rounded when

viewed laterally. Nasal groove rather short, narrow near the margin; nostrils

linear-oblong, sub-basal in the soft membrane. Lower mandible with the angle

extremely short, the dorsal outline straight or slightly decurved, the sides

erect, the edges united into a very thin blade which fits into the narrow groove

of the upper mandible, the tip rounded or abrupt when viewed laterally.

Head rather large, oblong, considerably elevated in front. Neck short and

thick. Body short, ovate, and compact. Feet short, moderately stout; tibia

bare below, with narrow transverse scutella before and behind; tarsus short,

moderately compressed, anteriorly covered with broad scutella, reticulated on

the sides and behind; toes very small; the first extremely short, and free; the

inner much shorter than the outer, which is but slightly exceeded by the middle

toe; the webs very deeply concave at the margin, especially the inner. Claws

long, compressed, tapering, slightly arched, rather obtuse, the inner edge of

the middle toe dilated and extremely thin. Plumage moderately full, soft, and

blended; the feathers oblong and rounded. Wings extremely elongated, and very

narrow; the primary quills excessively long; the first longest, the rest rapidly

graduated; the secondaries short, broad, incurved, obliquely pointed, some of

the inner more elongated. Tail rather short, deeply forked, of twelve feathers,

disposed in two inclined planes.

Bill of a rich carmine, inclining to vermilion for about half its length,

the rest black. Iris hazel. Feet of the same colour as the base of the bill,

claws black. The upper parts are deep brownish-black; the secondary quills, and

four or five of the primaries, tipped with white; the latter on their inner web

chiefly. Tail-feathers black, broadly margined on both sides with white, the

outer more extensively; the middle tail-coverts black, the lateral black on the

inner and white on the outer web. A broad band of white over the forehead,

extending to the fore part of the eye; cheeks and throat of the same colour; the

rest of the neck and lower parts in spring and summer of a delicate

cream-colour; axillary feathers, lower wing-coverts, and a large portion of the

secondary quills, white; the coverts along the edge of the wing black.

Length from point of upper mandible to end of tail 20 inches, to end of

wings 24 1/2, to end of claws 17; to carpal joint 8 1/4; extent of wings 48;

upper mandible 3 1/8; its edge 3 7/8; from base to point of lower mandible

4 1/2; depth of bill at the base 1; wing from flexure 15 3/4; tail to the fork

3 1/2; to end of longest feather 5 1/4; tarsus 1 1/4; hind toe and claw 4/12;

middle toe 10/12, its claw 4/12. Weight 13 oz.

The Female, which is smaller, is similar to the male, but with the

tail-feathers white excepting a longitudinal band including the shaft.

Length to end of tail 16 3/4, to end of wings 20 1/4, to end of claws

16 1/4, to carpus 8; extent of wings 44 1/2. Weight 10 oz.

After the first autumnal moult there is on the hind part of the neck a

broad band of white, mottled with greyish-black; the lower parts pure white, the

upper of a duller black; the bill and feet less richly coloured.

Length to end of tail, 16 3/4 inches, to end of wings 20, to end of claws

14 1/2, to carpus 6 3/8; extent of wings 42.

In some individuals at this period the mandibles are of equal length.

The palate is flat, with two longitudinal series of papillae directed

backwards. The upper mandible is extremely contracted, having internally only a

very narrow groove, into which is received the single thin edge of the lower

mandible. The posterior aperture of the nares is 1 3/12 inches long, with a

transverse line of papillae at the middle on each side, and another behind. The

tongue is sagittiform, 6 1/2 twelfths long, with two conical papillae at the

base, soft, fleshy, flat above, horny beneath. Aperture of the glottis 4 1/2

twelfths long, with numerous small papillae behind. Lobes of the liver equal,

1 1/2 inches long. The heart of moderate size, 1 1/12 long, 10 twelfths broad.

The oesophagus, of which only the lower portion, Fig. 1 [a], is seen in the figure, is 8 inches long, gradually contracts from a diameter of 1 inch to 4

twelfths, then enlarges until opposite the liver, where its greatest diameter is

1 4/12. Its external transverse fibres are very distinct, as are the internal

longitudinal. The proventriculus, [b], is 9 twelfths long, its glandules

extremely small and numerous, roundish, scarcely a quarter of a twelfth in

length. The stomach, [c d e], is rather small, oblong, 1 inch 4 twelfths

long, 11 twelfths broad, muscular, with the lateral muscles moderate. The

cuticular lining of the stomach is disposed in nine broad longitudinal rugae of

a light red colour, as in the smaller Gulls and Terns. Its lateral muscles are

about 4 twelfths thick, the tendons, [e], 6 twelfths in diameter. The intestine

is 2 feet 4 inches long, its average diameter 2 1/2 twelfths. The rectum is 2

inches long. One of the coeca is 4, the other 3 twelfths, their diameter 1 1/4

twelfths.

In another individual, the intestine is 22 1/4 inches long; the coeca 5

twelfths long, 1 twelfth in diameter; the rectum 1 3/4 inches long; the cloaca 9

twelfths in diameter.

The trachea is 5 3/4 inches long, round, but not ossified, its diameter at

the top 5 twelfths, contracting gradually to 2 1/2 twelfths. The lateral or

contractor muscles are small; the sterno-tracheal slender; there is a pair of

inferior laryngeals, going to the last ring of the trachea. The number of rings

is 90, and a large inferior ring. The bronchi are of moderate length, but

wider, their diameter being 3 1/2 twelfths at the upper part; the number of

their half-rings about 18.

The digestive organs of this bird are precisely similar to those of the

Terns and smaller Gulls, to which it is also allied by many of its habits.

| Next >> |