| Family XLII. LARINAE. GULLS. GENUS II. STERNA, Linn. TERN. |

Next >> |

Family |

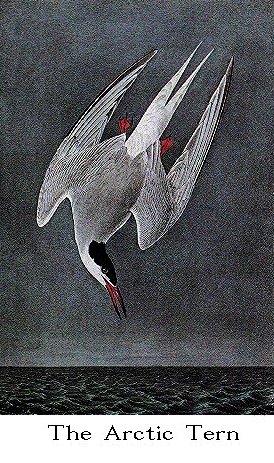

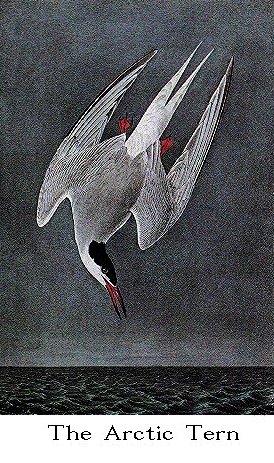

THE ARCTIC TERN. [Arctic Tern.] |

| Genus | STERNA ARCTICA, Temm. [Sterna paradisaea.] |

Light as a sylph, the Arctic Tern dances through the air above and around

you. The graces, one might imagine, had taught it to perform those beautiful

gambols which you see it display the moment you approach the spot which it has

chosen for its nest. Over many a league of ocean has it passed, regardless of

the dangers and difficulties that might deter a more considerate traveller. Now

over some solitary green isle, a creek or an extensive bay, it sweeps, now over

the expanse of the boundless sea; at length it has reached the distant regions

of the north, and amidst the floating icebergs stoops to pick up a shrimp. It

betakes itself to the borders of a lonely sand-bank, or a low rocky island;

there side by side the males and the females alight, and congratulate each other

on the happy termination of their long journey. Little care is required to form

a cradle for their progeny; in a short time the variegated eggs are deposited,

the little Terns soon burst the shell, and in a few days hobble towards the edge

of the water, as if to save their fond parents trouble; feathers now sprout on

their wings, and gradually invest their whole body; the young birds at length

rise on wing, and follow their friends to sea. But now the brief summer of the

north is ended, dark clouds obscure the sun, a snow-storm advances from the

polar lands, and before it skim the buoyant Terns, rejoicing at the prospect of

returning to the southern regions.

The day after our arrival at the Magdalene Islands, the weather was

beautiful, although a stiff breeze blew from the south-west. I landed with my

party at an early hour, and we felt as if at a half-way house on our journey

from Nova Scotia to Labrador. Some of us ascended the more elevated parts of

those interesting islands, while others walked along the shores. A clean

sand-beach lay before us, and we proceeded over it, until having reached a kind

of peninsula, we were brought to a stand. The Piping Plover ran and flew

swiftly before us, emitting its soft and mellow notes, while some dozens of

Arctic Terns were plunging into the waters, capturing a tiny fish or shrimp at

every dash. Until that moment this Tern had not been familiar to me, and as I

admired its easy and graceful motions, I felt agitated with a desire to possess

it. Our guns were accordingly charged with mustard-seed shot, and one after

another you might have seen the gentle birds come whirling down upon the waters.

But previous to this I had marked their mode of flight, their manner of

procuring their prey, and their notes, that I might be able to finish the

picture from life. Alas, poor things! how well do I remember the pain it gave

me, to be thus obliged to pass and execute sentence upon them. At that very

moment I thought of those long-past times, when individuals of my own species

were similarly treated; but I excused myself with the plea of necessity, as I

recharged my double gun. As soon as a sufficient number of males and females

lay dead at our feet, we retired from the water's edge, to watch the motions of

the survivors, among whom confusion and dismay prevailed, as they dashed close

over our heads, and vociferated their maledictions. We did not, however, depart

until we had tried a curious experiment for the third time. A female had been

shot, and lay dead on the water for a considerable while. Her mate, whom I was

unwilling to destroy, alighted upon her, and attempted to caress her, as if she

had been alive. The same circumstance took place three different times, on our

throwing the dead bird on the water. Something of the same nature I have

related in my article on the Wild Turkey. All this happened in the month of

June 1833, when none of the Arctic Terns had yet produced eggs, although we

found them nearly ready to lay, as were the Piping Plovers.

Our schooner now sailed onward, and carried us to the dreary shores of

Labrador. There, after some search, we met with a great flock of Arctic Terns

breeding on a small island slightly elevated above the sea. Myriads of these

birds were there sitting on their eggs. The individuals were older than those

which we had seen on the Magdalene Islands; for the more advanced in life the

individuals of any species are, the more anxious are they to reproduce, the

sooner do they proceed to their summer residence, and the more extensive is the

range of their migration northward. On the other hand, the younger the bird is,

the farther south it removes during winter, both because it thus enjoys a milder

climate, and requires less exertion in procuring its food; whereas the older

individuals not only have a stronger constitution, but are more expert in

discovering and securing their prey, so that it is not necessary for them to

extend their journey so far.

The Arctic Tern is found with us on the eastern coasts of the United States

only, where it appears, from the shores of New Jersey northwards, in autumn, and

whence it departs in early spring. No sooner have the winter tempests subsided,

than it is observed gliding along the coast, together with many other birds. In

the beginning of March, you see it following the sinuosities of the shores, some

passing directly from the Sable Islands off the Bay of Fundy and Newfoundland

into Baffin's Bay; others, younger, and unwilling to encounter the perils of a

more extended flight, passing up the Gulf of St. Lawrence, either through the

Straits of Cansso, or the broader channel between Cape Breton and Newfoundland,

and betaking themselves to the Magdalene Islands and the coasts of Labrador.

While at American Harbour in June 1833, my son and some of his companions

met with a low rocky island, on which hundreds of these Terns had deposited

their eggs. No other species was seen there; the birds were mostly sitting,

and, on the landing of the party, they all rose as if in the greatest

consternation, hovered over their heads, and left their eggs to the mercy of the

intruders, who carried off a basketful of them, with a few of the birds

themselves.

On the 18th of the same month, the Arctic Terns were found breeding on

another island in considerable numbers; many dozens of their eggs were gathered,

and delicious food indeed they proved to be. The full number of their eggs is

three, but as it was early in the season many had only two. Their average

dimensions were an inch and a quarter in length, and five-eighths in their

greatest breadth; they were oval, but rather sharp at the smaller ends; their

ground-colour a light olive, irregularly covered with patches of dark umber,

larger towards the round end. They were deposited on the rocks wherever there

was any grass, but no nest had been formed for their reception. They differed

extremely in their colour, indeed quite as much as those of the Sandwich Tern.

As we approached the little island, they all rose in the air, and flew high over

our heads, screaming loudly, which they continued to do until we left the place.

Several were shot, and as each fell the rest immediately plunged through the air

after it. Whenever one was wounded so slightly as to be able to make off, it

was lost to us, and the rest followed it. Only a very few of those which we saw

and shot had the bill entirely red, and those which had were evidently older

birds. Some exhibited a considerable portion of the point tinged with

brownish-black, yet all of them could easily be distinguished from the Sterna

Hirundo, first by their smaller size, shorter tarsi, more delicate bill, and

greater curvature of the outer part of their wings; and secondly, by the leaden

tint of their lower parts, from the neck to the tail, those parts in Sterno

Hirundo being pure white. The back is also of a deeper blue in the Arctic Tern.

The long tail-feathers were much shorter in the females than in the males, but

M. TEMMINCK is wrong in saying that this bird has the tail proportionally longer

than that of other species, the Roseate Tern having it of much greater length,

considering its diminutive size.

At the beginning of the first autumn, the plumage of the young so much

resembles that of the young of Sterna Hirundo, that a person, not paying

attention to the tarsi and feet, might readily confound them together. Yet even

at this early age, there are strong indications of the bluish tint on the under

parts. The longest tail-feathers at this period do not extend more than two

inches beyond the rest; the upper parts of the body are mottled with brown, as

in all the other species, and in Gulls. The mantle of this, as of all other

Terns, assumes its permanent hue before any part of the wings. On the 5th of

August, in Labrador, the young birds were gambolling along with their parents,

over the shores of Bras d'Or Harbour, and when we left that country the Terns

still remained, so that I am unable to state at what particular period they

commence their journey southward.

The notes of this species resemble the syllables creek, creek, and are

often repeated while the bird is on wing. During autumn it follows the

sinuosities of the shores of the bays and inlets, ascending against the ebb, and

returning to meet the tide, which enables it to procure its food in succession

while it keeps on its course. I have only farther to mention a curious fact,

which is, that all the Terns which breed in the northern parts of the United

States, and in regions still nearer the pole, sit closely on their eggs, while

the small species that breed to the southward incubate only during night, or in

rainy weather.

STERNA ARCTICA, Bonap. Syn., p. 354.

STERNA ARCTICA, Arctic Tern, Swains. and Rich. F. Bor. Amer., vol. ii.p. 414.

ARCTIC TERN, Nutt. Man., vol. ii. p. 275.

ARCTIC TERN, Sterna arctica., Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. iii. p. 366.

Male, 15 1/2, 32.

Along the coast of the Atlantic in autumn and winter, sometimes as far as

New Jersey. Common in Maine, Nova Scotia, and Labrador, where it breeds in

multitudes, as well as on the Magdalene Islands, and on the shores of the Arctic

Seas. Migratory.

Adult Male in spring.

Bill about the same length as the head, slender, tapering, compressed,

nearly straight, very acute. Upper mandible with the dorsal line slightly

arched, the ridge rather broad and convex at the base, narrow towards the end,

the sides convex, the edges sharp and inflected, the tip acute. Nasal groove

extended beyond the nostrils nearly to the tip; nostrils basal, linear, direct,

pervious. Lower mandible with the angle extremely narrow, very acute, extending

beyond the middle, the dorsal line straight, the sides erect and slightly

convex, the sharp edges inflected, the tip extremely acute.

Head of moderate size, oblong; neck of moderate length; body very slender.

Feet very small; tibia bare for a considerable space; tarsus extremely short,

slender, roundish, covered anteriorly with small scutella, laterally and behind

with reticular scales; toes very small, slender, the first extremely small, the

third longest, the fourth nearly as long, the second much shorter, all

scutellate above, the anterior connected by reticulated webs having a concave

margin; claws arched, compressed, acute, that of hind toe smallest, of middle

toe by much the largest, and having the inner edge thin and dilated.

Plumage soft, close, blended, very short on the fore part of the head; the

feathers in general broad and rounded. Wings very long, narrow and pointed;

primary quills tapering, slightly curved inwards, the first longest, the rest

rapidly graduated; secondary short, broad, incurved, rounded, the inner more

tapering. Tail long, very deeply forked, of twelve feathers, of which the outer

are tapering, the middle short and rounded.

Bill, mouth, and feet vermilion tinged with carmine. Iris brown. The

upper part of the head and elongated occipital feathers greenish-black; the

sides of the head and chin white; the upper parts pale greyish-blue, the rump

lighter, the tail white, excepting the outer webs of the two lateral feathers

which are dusky-grey; primaries dusky towards the ends, the two outer with their

outer webs blackish, all with the greater part of the inner web white;

secondaries tipped with white. Neck, breast and sides pale greyish-blue, like

the upper parts, but lighter; abdomen, under tail-coverts, and lower surfaces of

wings and tail white.

Length to end of tail 15 1/2 inches, to end of wings 13 1/2, to end of

claws 9 3/4; extent of wings 32; wing from flexure 10 1/2; tail to end of

shortest feathers 3 1/4, to end of longest 7 1/2; bill along the ridge 1 1/4,

along the edge of lower mandible 1 10/12; tarsus 8/12; middle toe (8 1/2)/12,

its claw (2 1/2)/12. Weight 2 3/4 oz.

| Next >> |