| Family XLII. LARINAE. GULLS. GENUS III. LARUS, Linn. GULL. |

Next >> |

Family |

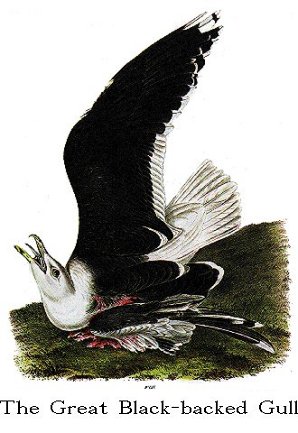

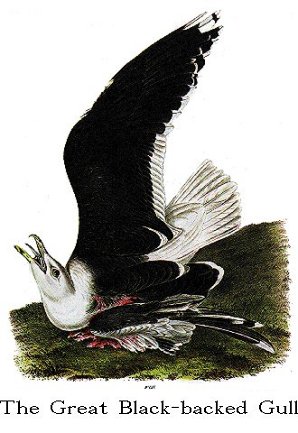

THE GREAT BLACK-BACKED GULL. [Great Black-backed Gull.] |

| Genus | LARUS MARINUS, Linn. [Larus marinus.] |

High in the thin keen air, far above the rugged crags of the desolate

shores of Labrador, proudly sails the tyrant Gull, floating along on almost

motionless wing, like an Eagle in his calm and majestic flight. On widely

extended pinions, he moves in large circles, constantly eyeing the objects

below. Harsh and loud are his cries, and with no pleasant feeling do they come

on the winged multitudes below. Now onward he sweeps, passes over each rocky

bay, visits the little islands, and shoots off towards the mossy heaths,

attracted perhaps by the notes of the Grouse or some other birds. As he flies

over each estuary, lake, or pool, the breeding birds prepare to defend their

unfledged broods, or ensure their escape from the powerful beak of their

remorseless spoiler. Even the shoals of the finny tribes sink deeper into the

waters as he approaches; the young birds become silent in their nests or seek

for safety in the clefts of the rocks; the Guillemots and Gannets dread to look

up, and the other Gulls, unable to cope with the destroyer, give way as he

advances. Far off among the rolling billows, he spies the carcass of some

monster of the deep, and, on steady wing, glides off towards it. Alighting on

the huge whale, he throws upwards his head, opens his bill, and, louder and

fiercer than ever, sends his cries through the air. Leisurely he walks over the

putrid mass, and now, assured that all is safe, he tears, tugs, and swallows

piece after piece, until he is crammed to the throat, when he lays himself down

surfeited and exhausted, to rest for awhile in the feeble sheen of the northern

sun. Great, however, are the powers of his stomach, and ere long the

half-putrid food which, vulture-like, he has devoured, is digested. Like all

gluttons, he loves variety, and away he flies to some well-known isle, where

thousands of young birds or eggs are to be found. There, without remorse, he

breaks the shells, swallows their contents, and begins leisurely to devour the

helpless young. Neither the cries of the parents, nor all their attempts to

drive the plunderer away, can induce him to desist until he has again satisfied

his ever-craving appetite. But although tyrannical, the Great Gull is a coward,

and meanly does he sneak off when he sees the Skua fly up, which, smaller as it

is, yet evinces a thoughtless intrepidity, that strikes the ravenous and

merciless bird with terror.

If we compare this species with some other of its tribe, and mark its great

size, its powerful flight, and its robust constitution, we cannot but wonder to

find its range so limited during the breeding season. Few individuals are to be

found northward of the entrance into Baffin's Bay, and rarely are they met with

beyond this, as no mention is made of them by Dr. RICHARDSON in the Fauna

Boreali-Americana. Along our coast, none breed farther south than the eastern

extremity of Maine. The western shores of Labrador, along an extent of about

three hundred miles, afford the stations to which this species resorts during

spring and summer; there it is abundant, and there it was that I studied its

habits.

The farthest limits of the winter migrations of the young, so far as I have

observed, are the middle portions of the eastern coast of the Floridas. While

at St. Augustine, in the winter of 1831, I saw several pairs keeping, company

with the young Brown Pelican, more as a matter of interest than of friendship,

as they frequently chased them as if to force them to disgorge a portion of

their earnings, acting much in the same manner as the Lestris does toward the

smaller Gulls, but without any effect. They were extremely shy, alighted only

on the outer edges of the outer sand-bars, and could not be approached, as they

regularly walked off before my party the moment any of us moved towards them,

until reaching the last projecting point, they flew off, and never stopped while

in sight. At what period they left that coast I am unable to say. Some are

seen scattered along our sea-shores, from the Floridas to the Middle States,

there being but few old birds among them; but the species does not become

abundant until beyond the eastern extremities of the Connecticut and Long

Island, when their number greatly increases the farther you proceed. On the

whole of that extensive range, these birds are very shy and wary, and those

which are procured are merely "chance shots." They seldom advance far up the

bays, unless forced to do so by severe weather or heavy gales; and although I

have seen this bird on our great lakes, I do not remember having ever observed

an individual on any of our eastern rivers, at a distance from the sea, whereas

the Larus argentatus is frequently found in such places.

Towards the commencement of summer, these wandering birds are seen

abandoning the waters of the ocean to tarry for awhile on the wild shores of

Labrador, dreary and desolate to man, but to them delightful as affording all

that they can desire. One by one they arrive, the older individuals first. As

they view from afar the land of their birth, that moment they emit their loud

cries, with all the joy a traveller feels when approaching his loved home. The

males sooner or later fall in with the females of their choice, and together

they proceed to some secluded sand-bar, where they fill the air with their

furious laughs until the rocks echo again. Should the student of nature happen

to be a distant spectator of these meetings, he too must have much enjoyment.

Each male bows, moves around his mate, and no doubt discloses to her the ardour

of his love. Matters are managed to the satisfaction of all parties, yet day

after day for awhile, at the retreat of the waters, they meet as if by mutual

agreement. Now you see them dressing their plumage, DOW partially expanding

their wings to the sun; some lay themselves comfortably down on the sand, while

others, supported by one foot, stand side by side. The waters again advance,

and the Gulls all move off in search of food. At length the time has arrived;

small parties of a few pairs fly towards the desert isles. Some remain in the

nearest to prepare their nests, the rest proceed, until each pair has found a

suitable retreat, and before a fortnight has elapsed, incubation has commenced.

The nest of this species is usually placed on the bare rock of some low

island, sometimes beneath a projecting shelf, sometimes in a wide fissure. In

Labrador it is formed of moss and sea-weeds carefully arranged, and has a

diameter of about two feet, being raised on the edges to the height of five or

six inches, but seldom more than two inches thick in the centre, where feathers,

dry grass, and other materials are added. The eggs are three, and in no

instance have I found more. They are two inches and seven-eighths in length, by

two inches and one-eighth in breadth, broadly ovate, rough but not granulated,

of a pale earthy greenish-grey colour, irregularly blotched and spotted with

brownish-black, dark umber, and dull purple. Like those of most other Gulls,

they afford good eating. This species lays from the middle of May to that of

June, and raises only one brood in the season. The birds never leave their eggs

for any length of time, until the young make their appearance. Both sexes

incubate, the sitting bird being supplied with food by the other. During the

first week, the young are fed by having their supplies disgorged into their

bill, but when they have attained some size, the food is dropped beside or

before them. When they are approached by man, they walk with considerable speed

towards some hiding place, or to the nearest projecting ledge, beneath which

they squat. When five or six weeks old, they take to the water, to ensure their

escape, and swim with great buoyancy. If caught, they cry in the manner of

their parents. On the 18th of June, several small ones were procured and placed

on the deck of the Ripley, where they walked with ease and picked up the food

thrown to them. As soon as one was about to swallow its portion, another would

run up, seize it, tug at it, and if stronger, carry it off and devour it. On

the 23d of that month, two individuals, several weeks old, and partly fledged,

were also brought on board. Their notes, although feeble, perfectly resembled

those of their parents. They ate greedily of every thing that was offered to

them. When fatigued they sat with their tarsi placed on the ground and extended

forward, in the manner of all the Herons, which gave them a very ludicrous

appearance. Ere a month had elapsed, they appeared to have formed a complete

acquaintance with the cook and several of the sailors, had become quite fat, and

conducted themselves much like Vultures, for if a dead Duck, or even a Gull of

their own species, were thrown to them, they would tear it in pieces, drink the

blood, and swallow the flesh in large morsels, each trying to rob the others of

what they had torn from the carcass. They never drank water, but not

unfrequently washed the blood and filth from their bills, by immersing them and

then shaking the head violently. These birds were fed until they were nearly

able to fly. Now and then, the sailors would throw them overboard while we were

in harbour. This seemed to gratify the birds as well as the sailors, for they

would swim about, wash themselves, and dress their plumage, after which they

would make for the sides, and would be taken on board. During a violent gale,

one night, while we were at anchor in the harbour of Bras d'Or, our bark rolled

heavily, and one of our pets went over the side and swam to the shore, where,

after considerable search next day, it was found shivering by the lee of a rock.

On being brought to its brothers, it was pleasant to see their mutual

congratulations, which were extremely animated. Before we left the coast, they

would sometimes fly of their own accord into the water to bathe, but could not

return to the deck without assistance, although they endeavoured to do so. I

had become much attached to them, and now and then thought they looked highly

interesting, as they lay panting on their sides on the deck, although the

thermometer did not rise above 55 degrees. Their enmity to my son's pointer was

quite remarkable, and as that animal was of a gentle and kindly disposition,

they would tease him, bite him, and drive him fairly from the deck into the

cabin. A few days after leaving St. George's Bay in Newfoundland, we were

assailed by a violent gale, and obliged to lie-to. Next day one of the Gulls

was washed overboard. It tried to reach the vessel again, but in vain; the gale

continued; the sailors told me the bird was swimming towards the shore, which

was not so far off as we could have wished, and which it probably reached in

safety. The other was given to my friend Lieutenant GREEN of the United States

army, at Eastport in Maine. In one of his letters to me the following winter,

he said that the young Larus marinus was quite a pet in the garrison, and doing

very well, but that no perceptible change had taken place in its plumage.

On referring to my journal again, I find that while we were at anchor at

the head of St. George's Bay, the sailors caught many codlings, of which each of

our young Gulls swallowed daily two, measuring from eight to ten inches in

length. It was curious to see them after such a meal: the form of the fish

could be traced along the neck, which for awhile they were obliged to keep

stretched out; they gaped and were evidently suffering; yet they would not throw

tip the fish. About the time the young of this species are nearly able to fly,

they are killed in considerable numbers on their breeding-grounds, skinned and

salted for the settlers and resident fishermen of Labrador and Newfoundland, at

which latter place I saw piles of them. When they are able to shift for

themselves, their parents completely abandon them, and old and young go

separately in search of food.

The flight of the Great Black-backed Gull is firm, steady, at times

elegant, rather swift, and long protracted. While travelling, it usually flies

at the height of fifty or sixty yards, and proceeds in a direct course, with

easy, regulated flappings. Should the weather prove tempestuous, this Gull,

like most others, skims over the surface of the waters or the land within a few

yards or even feet, meeting the gale, but not yielding to it, and forcing its

way against the strongest wind. In calm weather and sunshine, at all seasons of

the year, it is fond of soaring to a great height, where it flies about

leisurely and with considerable elegance for half an hour or so, in the manner

of Eagles, Vultures, and Ravens. Now and then, while pursuing a bird of its own

species, or trying to escape from an enemy, it passes through the air with rapid

boundings, which, however, do not continue long, and as soon as they are over it

rises and slowly sails in circles. When man encroaches on its domains, it keeps

over him at a safe distance, not sailing so much as moving to either side with

continued flappings. To secure the fishes on which it more usually preys, it

sweeps downwards with velocity, and as it glides over the spot, picks up its

prey with its bill. If the fish be small, the Gull swallows it on wing, but if

large, it either alights on the water, or flies to the nearest shore to devour

it.

Although a comparatively silent bird for three-fourths of the year, the

Great Black-backed Gull becomes very noisy at the approach of the breeding

season, and continues so until the young are well fledged, after which it

resumes its silence. Its common notes, when it is interrupted or surprised,

sound like cack, cack, cack. While courting, they are softer and more

lengthened, and resemble the syllables cawah, which are often repeated as it

sails in circles or otherwise, within view of its mate or its place of abode.

This species walks well, moving firmly and with an air of importance. On

the water it swims lightly but slowly, and may soon be overtaken by a boat. It

has no power of diving although at times, when searching for food along the

shores, it will enter the water on seeing a crab or a lobster, to seize it, in

which it at times succeeds. I saw one at Labrador plunge after a large crab in

about two feet of water, when, after a tug, it hauled it ashore, where it

devoured it in my sight. I watched its movements with a glass, and could easily

observe how it tore the crab to pieces, swallowed its body, leaving the shell

and the claws, after which it flew off to its young and disgorged before them.

It is extremely voracious, and devours all sorts of food excepting

vegetables, even the most putrid carrion, but prefers fresh fish, young birds,

or small quadrupeds, whenever they can be procured. It sucks the eggs of every

bird it can find, thus destroying great numbers of them, as well as the parents,

if weak or helpless. I have frequently seen these Gulls attack a flock of young

Ducks while swimming beside their mother, when the latter, if small, would have

to take to wing, and the former would all dive, but were often caught on rising

to the surface, unless they happened to be among rushes. The Eider Duck is the

only one of the tribe that risks her life, on such occasions, to save that of

her young. She will frequently rise from the water, as her brood disappear

beneath, and keep the Gull at bay, or harass it until her little ones are safe

under some shelving rocks, when she flies off in another direction, leaving the

enemy to digest his disappointment. But while the poor Duck is sitting on her

eggs in any open situation, the marauder assails her, and forces her off, when

he sucks the eggs in her very sight. Young Grouse are also the prey of this

Gull, which chases them over the moss-covered rocks, and devours them before

their parents. It follows the shoals of fishes for hours at a time, and usually

with great success. On the coast of Labrador, I frequently saw these birds

seize flounders on the edges of the shallows; they often attempted to swallow

them whole, but, finding this impracticable, removed to some rock, beat them,

and tore them to pieces. They appear to digest feathers, bones, and other hard

substances with ease, seldom disgorging their food, unless for the purpose of

feeding their young or mates, or when wounded and approached by man, or when

pursued by some bird of greater power. While at Boston in Massachusetts, one

cold winter morning, I saw one of these Gulls take up an eel, about fifteen or

eighteen inches in length, from a mud bank. The Gull rose with difficulty, and

after some trouble managed to gulp the head of the fish, and flew towards the

shore with it, when a White-headed Eagle made its appearance, and soon overtook

the Gull, which reluctantly gave up the eel, on which the Eagle glided towards

it, and, seizing it with its talons, before it reached the water, carried it

off.

This Gull is excessively shy and vigilant, so that even at Labrador we

found it difficult to procure it, nor did we succeed in obtaining more than

about a dozen old birds, and that only by stratagem. They watched our movements

with so much care as never to fly past a rock behind which one of the party

might be likely to lie concealed. None were shot near the nests when they were

sitting on their eggs, and only one female attempted to rescue her young, and

was shot as she accidentally flew within distance. The time to surprise them

was during violent gales, for then they flew close to the tops of the highest

rocks, where we took care to conceal ourselves for the purpose. When we

approached the rocky islets on which they bred, they left the place as soon as

they became aware of our intentions, cackled and barked loudly, and when we

returned, followed us at a distance more than a mile.

They begin to moult early in July. In the beginning of August the young

were seen searching for food by themselves, and even far apart. By the 12th of

that month they had all left Labrador. We saw them afterwards along the coast

of Newfoundland, and while crossing the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and found them

over the bays of Nova Scotia, as we proceeded southward. When old, their flesh

is tough and unfit for food. Their feathers are elastic, and good for pillows

and such purposes, but can rarely be procured in sufficient quantity.

The most remarkable circumstance relative to these birds is, that they

either associate with another species, giving rise to a hybrid brood, or that

when very old they lose the dark colour of the back, which is then of the same

tint as that of the Larus argentatus, or even lighter. This curious fact was

also remarked by the young gentlemen who accompanied me to Labrador; and

although it is impossible for me to clear up the doubts that may be naturally

entertained on this subject, whichever of the two suppositions is adopted, the

fact may yet be established and accounted for by persons who may have better

opportunities of watching them and studying their habits. No individuals of

Larus argentatus were, to my knowledge, seen on that coast during the three

months which I passed there, and the fishermen told us that the "saddle-backs

were the only large Gulls that ever breed there."

This bird must be of extraordinary longevity, as I have seen one that was

kept in a state of captivity more than thirty years. The following very

interesting account of the habits of a partially domesticated individual I owe

to my esteemed and learned friend Dr. NEILL of Edinburgh.

"In the course of the summer of 1818, a "big scoria" was brought to me by a

Newhaven fisher-boy, who mentioned that it had been picked up at sea, about the

mouth of the Frith of Forth. The bird was not then fully fledged: it was quite

uninjured: it quickly learned to feed on potatoes and kitchen refuse, along

with some Ducks; and it soon became more familiar than they, often peeping in at

the kitchen window in hopes of getting a bit of fat meat, which it relished

highly. It used to follow my servant PEGGY OLIVER about the doors, expanding

its wings and vociferating for food. After two moults I was agreeably surprised

to find it assuming the dark plumage of the back, and the shape and colour of

the bill of the Larus marinus, or Great Black-backed Gull; for I had hitherto

regarded it as merely a large specimen of the Lesser Black-backed (L. fuscus),

a pair of which I then possessed, but which had never allowed the new comer to

associate with them. The bird being perfectly tame, we did not take the

precaution of keeping the quills of one wing cut short, so as to prevent flight;

indeed, as it was often praised as a remarkably large and noble looking Sea-maw,

we did not like to disfigure it. In the winter of 1821-2, it got a companion in

a cock-heron, which had been wounded in Coldinghame Muir, brought to Edinburgh

alive, and kept for some weeks in a cellar in the old college, and then

presented to me by the late Mr. JOHN WILSON, the janitor,--a person remarkably

distinguished for his attachment to natural history pursuits. This Heron we

succeeded in taming completely, and it still (1835) remains with me, having the

whole garden to range in, the trees to roost upon, and access to the loch at

pleasure, the loch being the boundary of my garden. Some time in the spring of

1822, the large Gull was missing; and we ascertained (in some way that has now

escaped my memory) that it had not been stolen, nor killed, as we at first

supposed, but had taken flight, passing northwards over the village, and had

probably therefore gone to sea. Of course I gave up all expectation of ever

hearing more of it. It was not without surprise, therefore, that on going home

one day in the end of October of that year, I heard my servant calling out with

great exultation, "Sir, Big Gull is come back!" I accordingly found him walking

about in his old haunts in the garden, in company with, and recognising (as I am

firmly persuaded) his old friend the Heron. He disappeared in the evening, and

returned in the morning, for several days; when PEGGY OLIVER thought it best to

secure him. He evidently did not like confinement, and it was concerted that he

should be allowed his liberty, although he ran much risk of being shot on the

mill-pond by youthful sportsmen from Edinburgh. After this temporary captivity,

he was more cautious and shy than formerly; but still he made almost daily

visits to the garden, and picked up herrings or other food laid down for him.

In the beginning of March 1823 his visits ceased; and we saw no more of him till

late in the autumn of that year. These winter visits to Canonmills, and summer

excursions to the unknown breeding-place, were continued for years with great

uniformity: only I remarked that after the Gull lost his protectress, who died

in 1826  , he became more distant in his manners. In my note-book, under date

of 26th October, 1829, I find this entry: 'Old PEGGY's Great Black-backed Gull

arrived at the pond this morning, the seventh (or eighth) winter he has

regularly returned. He had a scorie with him, which was soon shot on the loch,

by some cockney sportsman.' The young bird, doubtless one of his offspring, had

its wing shattered, and continued alive in the middle of the pond, occasionally

screaming piteously, for two or three days, till relieved by death. The old

Gull immediately abandoned the place for that winter, as if reproaching us for

cruelty. By next autumn, however, he seemed to have forgotten the injury; for,

according to my record, '30th October, 1830. The Great Black-backed Gull once

more arrived at Canonmills garden.' The periods of arrival, residence, and

departure were nearly similar in the following year. But in 1832, not only

October, but the months of November and December passed away without Gull's

making his appearance, and I of course despaired of again seeing him. He did,

however, at length arrive. The following is the entry in my common-place book:

'Sunday, 6th January, 1833. This day the Great Black-back returned to the

mill-pond, for (I think) the eleventh season. He used to re-appear in October

in former years, and I concluded him dead or shot. He recognised my voice, and

hovered over my head.' He disappeared early in March as usual, and reappeared

at Canonmills on 23d December, 1833, being a fortnight earlier than the date of

his arrival in the preceding season, but six weeks later than the original

period of reappearance. He left in the beginning of March as usual, and I find

from my notes that he 'reappeared on 30th December, 1834, for the season, first

hovering around and then alighting on the pond as in former years.' The latest

entry is, '11th March, 1835. The Black-backed Gull was here yesterday, but has

not been seen to-day; nor do I expect to see him till November.'

, he became more distant in his manners. In my note-book, under date

of 26th October, 1829, I find this entry: 'Old PEGGY's Great Black-backed Gull

arrived at the pond this morning, the seventh (or eighth) winter he has

regularly returned. He had a scorie with him, which was soon shot on the loch,

by some cockney sportsman.' The young bird, doubtless one of his offspring, had

its wing shattered, and continued alive in the middle of the pond, occasionally

screaming piteously, for two or three days, till relieved by death. The old

Gull immediately abandoned the place for that winter, as if reproaching us for

cruelty. By next autumn, however, he seemed to have forgotten the injury; for,

according to my record, '30th October, 1830. The Great Black-backed Gull once

more arrived at Canonmills garden.' The periods of arrival, residence, and

departure were nearly similar in the following year. But in 1832, not only

October, but the months of November and December passed away without Gull's

making his appearance, and I of course despaired of again seeing him. He did,

however, at length arrive. The following is the entry in my common-place book:

'Sunday, 6th January, 1833. This day the Great Black-back returned to the

mill-pond, for (I think) the eleventh season. He used to re-appear in October

in former years, and I concluded him dead or shot. He recognised my voice, and

hovered over my head.' He disappeared early in March as usual, and reappeared

at Canonmills on 23d December, 1833, being a fortnight earlier than the date of

his arrival in the preceding season, but six weeks later than the original

period of reappearance. He left in the beginning of March as usual, and I find

from my notes that he 'reappeared on 30th December, 1834, for the season, first

hovering around and then alighting on the pond as in former years.' The latest

entry is, '11th March, 1835. The Black-backed Gull was here yesterday, but has

not been seen to-day; nor do I expect to see him till November.'

"This Gull has often attracted the attention of persons passing the village

of Canonmills, by reason of its sweeping along so low or near the ground, and on

account of the wide expanse of wing which it thus displays. It is well known to

the boys of the village as "NEILL's Gull," and has, I am aware, owed its safety

more than once to their interference, in informing passing sportsmen of its

history. When it first arrives in the autumn, it is in the regular habit of

making many circular sweeps around the pond and garden, at a considerable

elevation, as if reconnoitring; it then gradually lowers its flight, and gently

alights about the centre of the pond. Upon the gardener's mounting the

garden-wall with a fish in his hand, the Gull moves towards the overhanging

spray of some large willow-trees, so as to catch what may be thrown to him,

before it sinks in the water. There can be no doubt whatever of the identity of

the bird. Indeed, he unequivocally shews that he recognises my voice when I

call aloud 'Gull, Gull;' for whether he be on wing or afloat, he immediately

approaches me.

"A few pairs of the Great Black-backed Gull breed at the Bass Rock yearly,

and it seems highly probable that my specimen had originally been hatched there.

If I may be allowed a conjecture, I would suppose that, after attaining

maturity, he for some years resorted to the same spot for the purpose of

breeding; but that of late years, having lost his mate or encountered some other

disaster, he has extended his migration for that purpose to some very distant

locality, which has rendered his return to winter quarters six weeks later than

formerly."

LARUS MARINUS, Linn. Syst. Nat., vol. i. p. 225.

BLACK-BACKED GULL or COBB, Nutt. Man., vol. ii. p. 308.

GREAT BLACKED-BILLED GULL, Larus marinus, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. iii.p. 305; vol. v. p. 636.

Male, 29 1/2, 67.

Not uncommon during winter as far south as Florida, the young especially.

Common from New York to Labrador, where it breeds. Lake Erie, Ontario, the St.

Lawrence, Ohio, and Mississippi rivers. Columbia river.

Adult Male in summer.

Bill shorter than the head, robust, compressed, higher near the end than at

the base. Upper mandible with the dorsal line nearly straight at the base,

declinate and arched towards the end, the ridge convex, the sides slightly

convex, the edges sharp, inflected, arcuate-declinate towards the end, the tip

rather obtuse. Nasal groove rather long and narrow; nostril in its fore part,

lateral, longitudinal, linear, wider anteriorly, pervious. Lower mandible with

the angle long and narrow, the outline of the crura rather concave, as is that

of the remaining part of the mandible, a prominent angle being formed at their

meeting, the sides nearly flat, the edges sharp and inflected.

Head rather large, oblong, narrowed anteriorly. Neck of moderate length,

strong. Body full. Wings long. Feet of moderate length, rather slender; tibia

bare below; tarsus somewhat compressed, covered anteriorly with numerous

scutella, laterally with angular scales, behind with numerous small oblong

scales; hind toe very small and elevated, the fore toes of moderate length,

rather slender, the fourth longer than the second, the third longest, all

scutellate above, and connected by reticulated entire membranes, the lateral

toes margined externally with a narrow membrane. Claws small, slightly arched,

depressed, rounded, that of middle toe with an expanded inner margin.

The plumage in general is close, full, elastic, very soft and blended, on

the back rather compact. Wings very long, broad, acute, the first quill

longest, the second scarcely shorter, the rest of the primaries rather rapidly

graduated; secondaries broad and rounded, the inner narrower. Tail of moderate

length, even, of twelve rounded feathers.

Bill gamboge-yellow, the lower mandible bright carmine towards the end.

Edges of eyelids bright carmine, iris silvery. Feet yellow, claws black. The

head, neck, and all the lower parts, pure white; back and wings deep

blackish-grey tinged with purple, or dark slate-colour; the rump and tail white,

as are the edges of the wing, and a large portion of the extremities of all the

quills; the second, third, fourth, and fifth primaries have a broad band of

black across their ends, the inner web only of the second being so marked, in

some specimens however both webs. The oesophagus is very large, the gizzard

small, the intestine four feet long, and about the thickness of a goose quill.

Length to end of tail 29 3/4 inches, to end of wings 31 1/2, to end of

claws 29 1/4; extent of wings 67; wing from flexure 20; tail 9; bill along the

ridge 2 10/12, along the edge of lower mandible 3 9/12 its depth at the angle 1,

at the base 11/12; tarsus 3 2/12; middle toe 2 1/2, its claw 1/2. Weight 3 lbs.

The Female is similar to the male, but considerably less.

The Young, when fledged, have the bill brownish-black, the iris dark brown,

the feet as in the adult. The head and neck are greyish-white, streaked with

pale brownish-grey; the upper parts mottled with brownish-black, brownish-grey,

and dull white, the rump paler. The primary quills blackish-brown, slightly

tipped with brownish-white; the tail-feathers white, with a large brownish-black

patch towards the end, larger on the middle feathers, which are also barred

towards the base with dusky. The lower parts are greyish-white, the sides and

lower tail-coverts obscurely mottled with greyish-brown.

Male, from Dr. T. M. BREWER. The mouth is of moderate width, its breadth

being 1 inch 9 twelfths; the palate flat, with two very prominent papillate

ridges, and four series of intervening papillae; on the upper mandible beneath

are five ridges, and the horny edges are prominent and thin, but very strong;

the posterior aperture of the nares linear, 1 inch 9 twelfths long. The tongue

is 2 inches 2 twelfths in length, fleshy above, horny beneath, rather narrow,

deeply channelled, the base emarginate and finely papillate, the tip narrowly

rounded.

The left lobe of the liver is larger than the right, which, however, is

more elongated, being 4 inches in length, the other 3 inches; the gall-bladder

oblong, 1 inch 2 twelfths by 7 twelfths. There is a large accumulation of fat

under the parietes of the abdomen, and appended to the stomach.

The oesophagus is 14 inches long; at the commencement its width is 2 1/2

inches, it then contracts to 1 inch 9 twelfths, at the lower part of the neck

enlarges to 2 inches, and towards the proventriculus to 2 1/2 inches; it then

suddenly contracts at the commencement of the stomach. This organ is rather

small, and of an oblong form, 2 1/2 inches long, 1 inch 9 twelfths broad; the

lateral muscles of moderate size, the inferior prominent, the tendons large and

radiated; the epithelium extremely dense, thick, with strong, longitudinal

ridges, and of a bright red colour. It contains remains of crabs. The

provetitricular glands, which are very small, being 1 1/2 twelfths in length,

and 1/4 twelfth broad, form a belt 1 1/4 inches in breadth, traversed by very

prominent rugae, continuous with those of the stomach. The inner membrane of

the oesophagus is strongly plaited, and that part is capable of being distended

to 3 inches. The intestine is 50 inches long, its greatest width 4 1/2

twelfths; the coeca 1/2 inch long, 1/4 inch wide, their distance from the

extremity 5 inches; the rectum is 8 twelfths in width, and the cloaca forms a

globular dilatation 1 1/2 inches in diameter.

The trachea is 12 inches long; at the top 7 1/2 twelfths wide gradually

contracting to 4 1/2 twelfths, considerably flattened, its rings slightly

ossified, 148 in number, of moderate breadth, very thin, contracted in the

middle line before and behind; the last half ring is large, moderately arched.

In this, as in all the other Gulls, there is a pair of slender muscles arising

from the sides of the thyroid bone in front, separating from the trachea,

attaching themselves to the subcutaneous cellular tissue, and inserted into the

furcula. Another pair arise from the same bone in front, spreading over the

whole anterior surface of the trachea, then become collected on the sides, send

off a slip to the costal process of the sternum, and continue narrow, to be

inserted into the last arched half-ring of the trachea; thus forming what is

called a single pair of inferior laryngeal muscles. Bronchi wide, each with 28

half rings.  "PEGGY OLIVER was remarkable for the zeal and taste she displayed in the domesticating of uncommon animals, as well as in the culture of plants: her expertness in the latter department is noticed and praised by Mr. LOUDON in his Gardener's Magazine. Her funeral was attended by some of the most distinguished naturalists here, and, among others, by your friend Dr. MACCULLOCH of Pictou, who happened to be in Edinburgh at the time, and whose friendship I have also the happiness to enjoy."

"PEGGY OLIVER was remarkable for the zeal and taste she displayed in the domesticating of uncommon animals, as well as in the culture of plants: her expertness in the latter department is noticed and praised by Mr. LOUDON in his Gardener's Magazine. Her funeral was attended by some of the most distinguished naturalists here, and, among others, by your friend Dr. MACCULLOCH of Pictou, who happened to be in Edinburgh at the time, and whose friendship I have also the happiness to enjoy."

| Next >> |