| Family XLIV. ALCINAE. AUKS. GENUS II. ALCA, Linn. AUK. |

Next >> |

Family |

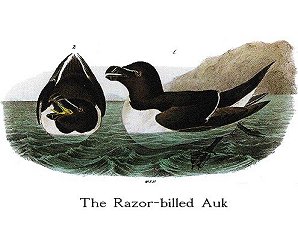

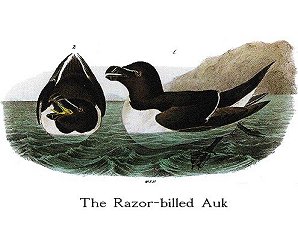

THE RAZOR-BILLED AUK. [Razorbill.] |

| Genus | ALCA TORDA, Linn. [Alca torda.] |

A few birds of this species occasionally go as far south as New York during winter; but beyond that parallel I never met with one. From Boston eastward

many are seen, and some breed on the Seal Islands off the entrance of the Bay of

Fundy. These Auks generally arrive on our Atlantic coast about the beginning of

November, and return northward to breed about the middle of April. During their

stay with us, they are generally seen singly. and at a greater distance from the

shores than the Guillemots or Puffins; and I have no doubt that they are able to

procure shell-fish at greater depths than these birds. I have observed them

fishing on banks where the bottom was fifteen or eighteen fathoms from the

surface, and, from the length of time that they remained under water, felt no

doubt that they dived to it. On my voyage round Nova Scotia and across the Gulf

of St. Lawrence, we saw some of them constantly. Some had eggs on the

Magdeleine Islands, where, as the inhabitants informed us, these birds arrive

about the middle of April, when the Gulf is still covered with ice. As we

proceeded towards Labrador, they passed us every now and then in long files,

flying at the height of a few yards from the water, in a rather undulating

manner, with a constant beat of the wings, often within musket-shot of our

vessel, and sometimes moving round us and coming so close as to induce us to

believe that they had a wish to alight. The thermometer indicated 44 degrees.

The sight of these files of birds passing swiftly by was extremely pleasing;

each bird would alternately turn towards us the pure white of its lower parts,

and again the jetty black of the upper. As I expected ere many days should pass

to have the gratification of inspecting their breeding-grounds, I experienced

great delight in observing them as they sped their flight toward the north.

After we had landed, we every day procured Auks, notwithstanding their

shyness, which exceeded that of almost all the other sea-birds. The fishermen

having given me an account of their principal breeding places, the Ripley

proceeded toward them apace. One fair afternoon we came in view of the renowned

Harbour of Whapati Guan, and already saw its curious beacon, which, being in

form like a huge mounted cannon placed on the elevated crest of a great rock,

produced a most striking effect. We knew that the harbour was within the

stupendous wall of rock before us, but our pilot, either from fear or want of

knowledge, refused to guide us to it, and our captain, leaving the vessel in

charge of the mate, was obliged to go off in a boat, to see if he could find a

passage. He was absent more than an hour. The Ripley stood off and on, the

yards were manned on the look-out, the sea was smooth and its waters as clear as

crystal, but the swell rose to a prodigious height as it passed sluggishly over

the great rocks that seemed to line the shallows over which we floated. We were

under no apprehension of personal danger, however, for we had several boats and

a very efficient crew; and besides, the shores were within cannon shot; but the

idea of losing our gallant bark and all our materials on so dismal a coast

haunted my mind, and at times those of my companions. From the tops our sailors

called out "Quite shallow here, sir." Up went the helm, and round swung the

Ripley like a duck taken by surprise. Then suddenly near another shoal we

passed, and were careful to keep a sharp look-out until our commander came up.

Springing upon the deck, and turning his quid rapidly from side to side, he

called out, "All hands square the yards," and whispered to me "All's safe, my

good sir." The schooner advanced towards the huge barrier, merrily as a fair

maiden to meet her beloved; now she doubles a sharp cape, forces her way through

a narrow pass; and lo! before you opens the noble harbour of Whapati Guan. All

around was calm and solemn; the waters were smooth as glass, the sails fell

against the masts, but the impetus which the vessel had received urged her

alone. The lead was heaved at every yard, and in a few minutes the anchor was

dropped.

Reader, I wish you had been there, that you might yourself describe the

wild scene that presented itself to our admiring gaze. We were separated from

the rolling swell of the Gulf of St. Lawrence by an immense wall of rock. Far

away toward the east and north, rugged mounds innumerable rose one above

another. Multitudes of frightened Cormorants croaked loudly as they passed us

in the air, and at a distance fled divers Guillemots and Auks. The mossy beds

around us shone with a brilliant verdure, the Lark piped its sweet notes on

high, and thousands of young codfish leaped along the surface of the deep cove

as if with joy. Such a harbour I had never seen before; such another, it is

probable, I may never see again; the noblest fleet that ever ploughed the ocean

might anchor in it in safety. To augment our pleasures, our captain some days

after piloted the Gulnare into it. But, you will say, "Where are the Auks, we

have lost sight of them entirely." Never fear, good reader, we are in a

delightful harbour, and anon you shall hear of them.

Winding up the basin toward the north-east, Captain Emery, myself, and some

sailors, all well armed, proceeded one day along the high and precipitous shores

to the distance of about four miles, and at last reached the desired spot. We

landed on a small rugged island. Our men were provided with long poles, having

hooks at their extremities. These sticks were introduced into the deep and

narrow fissures, from which we carefully drew the birds and eggs. One place, in

particular, was full of birds; it was an horizontal fissure, about two feet in

height, and thirty or forty yards in depth. We crawled slowly into it, and as

the birds affrighted flew hurriedly past us by hundreds, many of their eggs were

smashed. The farther we advanced, the more dismal did the cries of the birds

sound in our ears. Many of them, despairing of effecting their escape, crept

into the surrounding recesses. Having collected as many of them and their eggs

as we could, we returned, and glad were we once more to breathe the fresh air.

No sooner were we out than the cracks of the sailors' guns echoed among the

rocks. Rare fun to the tars, in fact, was every such trip, and, when we joined

them, they had a pile of Auks on the rocks near them. The birds flew directly

towards the muzzles of the guns, as readily as in any other course, and

therefore it needed little dexterity to shoot them.

When the Auks deposit their eggs along with the Guillemots, which they

sometimes do, they drop them in spots from which the water can escape without

injuring them; but when they breed in deep fissures, which is more frequently

the case, many of them lie close together, and the eggs are deposited on small

beds of pebbles or broken stones raised a couple of inches or more, to let the

water pass beneath them. Call this instinct if you will:--I really do not much

care; but you must permit me to admire the wonderful arrangements of that Nature

from which they have received so much useful knowledge. When they lay their

eggs in such an horizontal cavern as that which I have mentioned above, you find

them scattered at the distance of a few inches from each other; and there, as

well as in the fissures, they sit flat upon them like Ducks, for example,

whereas on an exposed rock, each bird stands almost upright upon its egg.

Another thing quite as curious, which I observed, is, that while in exposed

situations the Auk seldom lays more than one egg, yet in places of greater

security I have, in many instances, found two under a single bird. This may

perhaps astonish you, but I really cannot help it.

The Razor-billed Auks begin to drop their eggs in the beginning of May. In

July we found numerous young ones, although yet small. Their bill then scarcely

exhibited the form which it ultimately assumes. They were covered with down,

had a lisping note, but fed freely on shrimps and small bits of fish, the food

with which their parents supply them. They were very friendly towards each

other, differing greatly in this respect from the young Puffins, which were

continually quarrelling. They stood almost upright. Whenever a finger was

placed within their reach, they instantly seized it, and already evinced the

desire to bite severely so cordially manifested by the old birds of this

species, which in fact will hang to your hand until choked rather than let go

their hold. The latter when wounded threw themselves on their back, in the

manner of Hawks, and scratched fiercely with their claws. They walked and ran

on the rocks with considerable ease and celerity, taking to wing, however, as

soon as possible. When thus disturbed while breeding, they fly round the spot

many times before they alight again. Sometimes a whole flock will alight on the

water at some distance, to watch your departure, before they will venture to

return.

This bird lays one or two eggs, according to the nature of the place. The

eggs measure at an average three inches and one-eighth, by two and one-eighth,

and are generally pure white, greatly blotched with dark reddish-brown or black,

the spots generally forming a circle towards the larger end. They differ

considerably from those of the Common and the Thick-billed Guillemots, being

less blunted at the smaller end. The eggs afford excellent eating; the yolk is

of a pale orange colour, the white pale blue. The Eggers collect but few of the

eggs of this bird, they being more difficult to be obtained than those of the

Guillemot, of which they take vast numbers every season.

The food of the Razor-billed Auk consists of shrimps, various other marine

animals, and small fishes, as well as roe. Their flesh is by the fishers

considered good, and I found it tolerable, when well stewed, although it is dark

and therefore not prepossessing. The birds are two years in acquiring the full

size and form of their bill, and, when full grown, they weighed about a pound

and a half. The stomach is an oblong sac, the lower part of which is rather

muscular, and answers the purpose of a gizzard. In many I found scales,

remnants of fish, and pieces of shells. The intestines were, upwards of three

feet in length.

Immediately after the breeding season, these birds drop their quills, and

are quite unable to fly until the beginning of October, when they all leave

their breeding-grounds for the sea, and move southward. The young at this

period scarcely shew the white streak between the bill and the eye; their

cheeks, like those of the old birds at this time, and the fore part of the neck,

are dingy white, and remain so until the following spring, when the only

difference between the young and the old is, that the former have the bill

smaller and less furrowed, and the head more brown. The back, tail, and lower

parts do not seem to undergo any material change.

ALCA TORDA, Bonap. Syn., p. 431.

RAZOR-BILL, Alca Torda, Nutt. Man., vol. ii. p. 547.

RAZOR-BILLED AUK, Alca Torda, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. iii. p. 112; vol. v.p. 628.

Male, 17, 29 1/2.

Rare on the eastern coast of the United States, and only during winter.

Breeds in great numbers on the Gannet Rock in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, on the

shores of Newfoundland, and the western coast of Labrador, chiefly in the

fissures of rocks.

Adult Male in summer.

Bill shorter than the head, feathered as far as the nostrils, beyond which

it is very high, exceedingly compressed, and obliquely furrowed on the sides.

Upper mandible with the dorsal line curved so as to form the third of a circle,

the ridge extremely narrow but rounded, the sides nearly flat, with five

grooves, the one next the base deeper and more narrow, the edges inflected and

sharp, the tip decurved and obtuse. Nostrils medial, marginal, linear, short,

pervious, but concealed by the feathers. Lower mandible with the angle very

narrow, and having a horny triangular appendage, the base at first horizontal

and extremely narrow, then sloping forwards and rounded, the dorsal outline

rounded, towards the end concave, the sides slightly concave, the edges

inflected, the tip decurved.

Head large, oblong, anteriorly narrowed. Eyes small. Neck short and

strong. Body full, rather depressed. Wings small. Feet placed far behind,

short, rather strong; tibia bare a short way above the joint; tarsus very short,

compressed, anteriorly scutellate, laterally covered with reticulated angular

scales, posteriorly granulate. Hind toe wanting; toes of moderate length,

rather slender, scutellate above, connected by reticulated entire membranes, the

inner toe having also a projecting margin; outer toe slightly longer than middle

one; inner considerably shorter. Claws rather small, arched, compressed,

obtuse.

Plumage close, blended, very soft, on the head very short and velvety.

Wings short, curved, narrow, acute. Primary quills narrow, incurved, acute,

first longest, second slightly shorter, the rest rapidly graduated; secondary

quills very short, obliquely rounded. Tail short, tapering, of twelve narrow,

pointed feathers.

Bill black, with a white line across each mandible; inside of the mouth

gamboge-yellow. Iris deep hazel. Feet black. Fore part of neck below, and all

the lower parts, white; the rest black, the head, hind neck, and back, glossed

with olive-green, the throat and sides of the neck tinged with chocolate, the

wings with brown, the tips of the secondary quills, and a narrow line from the

bill to the eye, white.

Length to the end of tail 17 inches, to the end of claws 17 3/4; extent of

wings 29 1/2; wing from flexure 8 1/4; tail 4; bill along the ridge 1 7/12,

along the edge 2/12, its greatest depth 11/12; tarsus 1 2/12; middle toe 1 8/12,

its claw 5/12. Weight 1 1/2 pounds.

Adult Female in summer.

The female is precisely similar to the male.

The Young in their winter plumage have the colouring distributed as in the

old birds, but with the black duller, the wings more brown, the throat and sides

of the head mottled with white, the white line from the bill to the eye

existing, but the bill much smaller, without furrows or a white line.

The Old Birds in winter have the throat and sides of the neck mottled as

described above; but in other respects their colours are the same as in summer.

The gullet wide, dilated towards the lower extremity, its mucous coat

longitudinally corrugated; the proventriculus very wide and glandular; the

stomach rather small, oblong, muscular, with an inner, longitudinally corrugated

and horny cuticular coat. Pylorus very small; intestine near its commencement

4/12 of an inch in diameter, gradually contracted to the coeca, where it is

2/12; coeca half an inch long, tapering. The length of the gullet and stomach

together is 8, that of the intestines 41 inches.

On the palate are several series of reversed papillae, and two longitudinal

papillate ridges; on its anterior part are five prominent lines; the posterior

aperture of the nares linear, 1 inch in length; width of mouth 11 twelfths.

Tongue 1 1/4 inches long, fleshy, slender in its whole length, trigonal, flat

above, with a median groove, and tapering to a very thin horny point.

OEsophagus 8 1/2 inches long, its width along the neck 10 twelfths, but within

the thorax it forms an enormous sac 3 1/2 inches long, 1 inch 11 twelfths in

breadth; the proventricular glands very numerous, forming a complete belt 3 1/4

inches in length, and occupying almost the whole of the sac above mentioned.

Stomach very small, 10 twelfths long, 9 twelfths in breadth; its muscular coat

thin, the tendons round, and about 5 twelfths in breadth; the epithelium thin,

dense, and longitudinally rugous. Intestine 53 inches long, its average width 5

twelfths; the coeca 9 twelfths long, 1 1/2 twelfths in breadth, 2 inches 1

twelfth distant from the extremity; cloaca globular, and about 1 inch in

diameter.

Trachea 5 inches long, from 4 1/2 twelfths to 3 twelfths in width, a little

flattened; its rings 95, unossified. Bronchi very wide, of 18 half rings.

Cleido-tracheal muscles, lateral muscles, sterno-tracheal slips, and a single

pair of inferior laryngeal muscles.

| Next >> |