| Family XLIV. ALCINAE. AUKS. GENUS V. URIA, Lath. GUILLEMOT. |

Next >> |

Family |

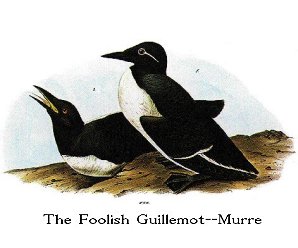

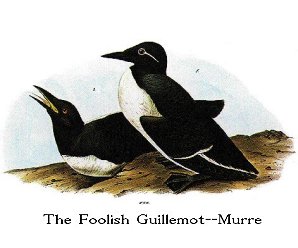

THE FOOLISH GUILLEMOT.--MURRE. [Common Murre.] |

| Genus | URIA TROILE, Linn. [Uria aalge.] |

This bird is seldom found farther south than the entrance of the Bay of New York, where, however, it appears only during severe winters, for being one of

the most hardy inhabitants of the northern regions, its constitution is such as

to enable it to bear without injury the rigours of their wintry climates. About

the bays near Boston the Guillemots are seen every year in greater or less

numbers, and from thence to the eastward they become gradually more abundant. A

very old gunner whom I employed while at Boston, during the winter of 1832-3,

assured me, that when he was a young man, this species bred on many of the rocky

islands about the mouth of the bay there; but that for about twenty years back

none remained after the first days of April, when they departed for the north in

company with the Thick-billed Guillemot, the Common Auk, the Puffin, and the

Eider and King Ducks, all of which visit these bays in hard weather. In the Bay

of Fundy, the Foolish Guillemot is very numerous, and is known by the name of

Murre, which it retains among all the eggers and fishermen of Newfoundland and

Labrador, where it breeds in myriads. To those countries, then, I must lead

you, good reader, as there we can with ease study the habits of these birds.

Stay on the deck of the Ripley by my side this clear and cold morning. See

how swiftly scuds our gallant bark, as she cuts her way through the foaming

billows, now inclining to the right and again to the left. Far in the east,

dark banks of low clouds indicate foul weather to the wary mariner, who watches

the approach of a northern storm with anxiety. Suddenly the wind changes; but

for this he has prepared; the topsails are snugged to their yards, and the rest

are securely reefed. A thick fog obscures all around us. The waters suddenly

checked in their former course, furiously war against those which now strike

them in front. The uproar increases, the bark is tossed on every side; now a

sweeping wave rushes against the bows, the vessel quivers, while down along her

deck violently pour the waters, rolling from side to side, seeking for a place

by which they may escape. At this moment all about you are in dismay save the

Guillemots. The sea is covered with these intrepid navigators of the deep.

Over each tumultuous billow they swim unconcerned on the very spray at the bow

of the vessel, and plunging as if with pleasure, up they come next moment at the

rudder. Others fly around in large circles, while thousands contend with the

breeze, moving directly against it in long lines, towards regions unknown to

all, save themselves and some other species of sea birds.

The Guillemots pair during their migrations;--many of them at least do so.

While on my way toward Labrador, they were constantly within sight, gambolling

over the surface of the water, the males courting the females, and the latter

receiving the caresses of their mates. These would at times rise erect in the

sea, swell their throats, and emit a hoarse puffing guttural note, to which the

females at once responded, with numerous noddings to their beaux. Then the pair

would rise, take a round in the air, re-alight, and seal the conjugal compact;

after which they flew or swam together for the season, and so closely, that

among multitudes on the wing or on the waves, one might easily distinguish a

mated pair.

Not far from Great Macatina Harbour lie the Murre Rocks, consisting of

several low islands, destitute of vegetation, and not rising high from the

waters. There thousands of Guillemots annually assemble in the beginning of

May, to deposit each its single egg, and raise its young. As you approach these

islands, the air becomes darkened with the multitudes of birds that fly about;

every square foot of the ground seems to be occupied by a Guillemot planted

erect as it were on the granite rock, but carefully warming its cherished egg.

All look toward the south, and if you are fronting them, the snowy white of

their bodies produces a very remarkable effect, for the birds at some distance

look as if they were destitute of head, so much does that part assimilate with

the dark hue of the rocks on which they stand. On the other hand, if you

approach them in the rear, the isle appears as if covered with a black pall.

Now land, and witness the consternation of the settlers! Each affrighted

leaves its egg, hastily runs a few steps, and launches into the air in silence.

Thrice around you they rapidly pass, to discover the object of your unwelcome

visit. If you begin to gather their eggs, or, still worse, to break them, in

order that they may lay others which you can pick up fresh, the Guillemots all

alight at some distance, on the bosom of the deep, and anxiously await your

departure. Eggs, green and white, and almost of every colour, are lying thick

over the whole rock; the ordure of the birds mingled with feathers, with the

refuse of half-hatched eggs partially sucked by rapacious Gulls, and with putrid

or dried carcasses of Guillemots, produces an intolerable stench; and no sooner

are all your baskets filled with eggs, than you are glad to abandon the isle to

its proper owners.

On one occasion, whilst at anchor at Great Macatina, one of our boats was

sent for eggs. The sailors had eight miles to pull before reaching the Murre

Islands, and yet ere many hours had elapsed, the boat was again alongside,

loaded to a few inches of the gunwale, with 2500 eggs! Many of them, however,

being addle, were thrown overboard. The order given to the tars had been to

bring only a few dozens; but, as they said, they had forgotten!

The eggs are unaccountably large for the size of the bird, their average

length being three inches and three-eighths, and their greatest breadth two

inches. They are pyriform or elongated, with a slight compression towards the

smaller end, which again rather swells and is rounded at the extremity. They

afford excellent food, being highly nutritive and palatable, whether boiled,

roasted, poached, or in omelets. The shell is rough to the touch, although not

granulated. Some are of a lively verdigris colour, others of different tints,

but all curiously splashed, as it were, with streaks or blotches of dark umber

and brown. My opinion, however, is, that, when first dropped, they are always

pure white, for on opening a good number of these birds, I found several

containing an egg ready for being laid, and of a pure white colour. The shell

is so firm that it does not easily break, and I have seen a quantity of these

eggs very carelessly removed from a basket into a boat without being damaged.

They are collected in astonishing quantities by "the eggers," and sent to

distant markets, where they are sold at from one to three cents each.

Although the Guillemots are continually harassed, their eggs being carried

off as soon as they are deposited, and as long as the birds can produce them,

yet they return to the same islands year after year, and, notwithstanding all

the efforts of their enemies, multiply their numbers.

The Foolish Guillemot, as I have said, lays only a single egg, which is the

case with the Thick-billed Guillemot also. The Razor-billed Auk lays two, and

the Black Guillemot usually three. I have assured myself of these facts, not

merely by observing the birds sitting on their eggs, but also by noticing the

following circumstances. The Foolish Guillemot, which lays only one, plucks the

feathers from its abdomen, which is thus left quite bare over a roundish space

just large enough to cover its single egg. The Thick-billed Guillemot does the

same. The Auk, on the contrary, forms two bare spots, separated by a ridge of

feathers. The Black Guillemot, to cover her three eggs, and to warm them all at

once, plucks a space bare quite across her belly. These observations were made

on numerous birds of all the species mentioned. In all of them, the males

incubate as well as the females, although the latter are more assiduous. When

the Guillemots are disturbed, they fly off in silence. The Auks, on the

contrary, emit a hoarse croaking note, which they repeat several times, as they

fly away from danger. The Foolish Guillemot seldom if ever attempts to bite,

whereas the Razor-billed Auk bites most severely, and clings to a person's hand

until choked. The plumage of all the birds of this family is extremely compact,

closely downed at the root, and difficult to be plucked. The fishermen and

eggers often use their skins with the feathers on as "comforters" round their

wrists. The flesh is dark, tough, and not very palatable; yet many of these

birds are eaten by the fishermen and sailors.

The young, which burst the egg about the beginning of July, are covered

with down of a brownish-black colour. When eight or ten days old they are still

downy, but have acquired considerable activity. As they grow up, they become

excessively fat, and seem to be more at ease on the water than on the land.

About the middle of August they follow their parents to the open sea, the latter

being then seldom able to fly, having dropped their quills; and by the middle of

September scarcely any of these birds are to be found on or near the islands on

which they breed, although great numbers spend the winter in those latitudes.

There is no perceptible difference between the sexes as to colour, but the

males are larger than the females. The white line that encircles the eye and

extends toward the hind head is common to both sexes, but occurs only in old

birds. Thousands of these Guillemots however breed without having yet acquired

it, there merely being indications of it to be seen on parting the feathers on

the place, where there is a natural division.

The flight of the Foolish Guillemot is rapid and greatly protracted, being

performed by quick and unintermitted beatings. They move through the air either

singly or in bands, in the latter case seldom keeping any very regular order.

Sometimes they seem to skim along the surface for miles, while at other times

they fly at the height of thirty or forty yards. They are expert divers, using

their wings like fins, and under water looking like winged fishes. They

frequently plunge at the flash of the gun, and disappear for a considerable

time. Before rising, they are obliged to run as it were on the water,

fluttering for many yards before they get fairly on wing.

Those which I kept alive for weeks on board the Ripley, walked about and

ran with ease, with the whole length of their tarsus touching the deck. They

took leaps on chests and other objects to raise themselves, but could not fly

without being elevated two or three feet, although when they are on the rocks,

and can take a run of eight or ten yards, they easily rise on wing.

The islands on which the Guillemots breed on the coast of Labrador, are

flattish at top, and it is there, on the bare rock, that they deposit their

eggs. I saw none standing on the shelvings of high rocks, although many breed

in such places in some parts of Europe. Their food consists of small fish,

shrimps, and other marine animals; and they swallow some gravel also.

URIA TROILE, Bonap. Syn., p. 424.

URIA TROILE, Foolish Guillemot, Swains. and Rich. F. Bor. Amer., vol. ii.p. 477.

FOOLISH GUILLEMOT, or MURRE, Nutt. Man., vol. ii. p. 526.

FOOLISH GUILLEMOT, Uria Troile, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. iii. p. 142.

Male, 17 1/2, 30.

More or less abundant during winter on the coast of Massachusetts and

Maine, rarely as far south as New York. Breeds in vast multitudes on the Rocky

Islands of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Newfoundland, and Labrador. Occasionally

found in Hudson's Bay.

Adult Male, in summer.

Bill of moderate length, rather stout, tapering, compressed, acute. Upper

mandible with the dorsal line slightly curved, the ridge narrow, broader at the

base, the sides sloping, the edges short and inflected, the tip a little

decurved with a slight notch. Nasal groove broad, feathered; nostrils at its

lower edge, sub-basal, lateral, longitudinal, linear, pervious. Lower mandible

with the angle medial, narrow, the dorsal line sloping upwards, and straight,

the back very narrow, the sides nearly flat, the edges sharp and inflected.

Head oblong, depressed, narrowed before. Eyes rather small. Neck short

and thick. Body stout, rather depressed. Wings rather small. Feet short,

placed far behind; the greater part of the tibia concealed, its lower portion

bare; tarsus short, stout, compressed, anteriorly sharp, and covered with a

double row of scutella, the sides with angular scales; toes of moderate length,

the first wanting, the third nearly longest, the fourth longer than the second;

all covered above with numerous scutella, webbed, the lateral ones with small

margins; claws small, slightly arched, compressed, rather acute, the middle one

larger, with a dilated inner edge.

Plumage dense, very soft, blended; on the head very short. Wings rather

short, narrow, acute; primary quills curved, tapering, the first longest, the

second little shorter, the rest rapidly graduated; secondaries short, incurved,

broad, rounded. Tail very short, rounded, of twelve narrow feathers.

Bill black; inside of mouth gamboge-yellow. Iris dark brown. Feet black.

The general colour of the plumage is greyish-black on the upper parts; the sides

of the head and upper part of the neck black, tinged with brown. A white bar

across the wing, formed by the tips of the secondary quills, and a line of the

same encircling the eye, and extending behind it. The lower parts white.

Length to end of tail 17 1/2 inches, to end of claws 19 1/4, to end of

wings 17 1/2; extent of wings 30 inches; wing from flexure 7 1/2; tail 2; tarsus

1 3/12; middle toe 1 7/12, its claw 5/12. Weight 2 lbs.

Adult Female.

The female is similar to the male, and, when mature, has the white line

around and behind the eye.

| Next >> |