| Family V. CYPSELINAE. SWIFTS.

GENUS I. CHOETURA, Stephens. SPINE-TAIL. |

Next >> |

Family |

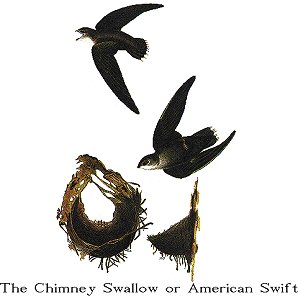

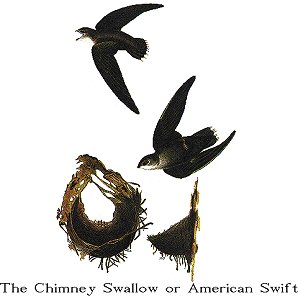

THE CHIMNEY SWALLOW., OR AMERICAN SWIFT. [Chimney Swift.] |

| Genus | CHOETURA PELASGIA, Temm. [Chaetura pelasgia.] |

Since the progress of civilization in our country has furnished thousands

of convenient places for this Swallow to breed in, safe from storms, snakes, or

quadrupeds, it has abandoned, with a judgment worthy of remark, its former

abodes in the hollows of trees, and taken possession of the chimneys which emit

no smoke in the summer season. For this reason, no doubt, it has obtained the

name by which it is generally known. I well remember the time when, in Lower

Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois, many resorted to excavated branches and trunks,

for the purpose of breeding; nay, so strong is the influence of original habit,

that not a few still betake themselves to such places, not only to roost, but

also to breed, especially in those wild portions of our country that can

scarcely be said to be inhabited. In such instances, they appear to be as nice

in the choice of a tree, as they generally are in our cities in the choice of a

chimney, wherein to roost. Sycamores of gigantic growth, and having a mere

shell of bark and wood to support them, seem to suit them best, and wherever I

have met with one of those patriarchs of the forest rendered habitable by decay,

there I have found the Swallows breeding in spring and summer, and afterwards

roosting until the time of their departure. I had a tree of this kind cut down,

which contained about thirty of their nests in its trunk, and one in each of the

hollow branches.

The nest, whether placed in a tree or chimney, consists of small dry twigs,

which are procured by the birds in a singular manner. While on wing, the

Chimney Swallows are seen in great numbers whirling round the tops of some

decayed or dead tree, as if in pursuit of their insect prey. Their movements at

this time are extremely rapid; they throw their body suddenly against the twig,

grapple it with their feet, and by an instantaneous jerk, snap it off short, and

proceed with it to the place intended for the nest. The Frigate Pelican

sometimes employs the same method for a similar purpose, carrying away the stick

in its bill, in place of holding it with its feet.

The Swallow fixes the first sticks on the wood, the rock, or the chimney

wall, by means of its saliva, arranging them in a semicircular form, crossing

and interweaving them, so as to extend the framework outwards. The whole is

afterwards glued together with saliva, which is spread around it for an inch or

more, to fasten it securely. When the nest is in a chimney, it is generally

placed on the east side, and is from five to eight feet from the entrance; but

in the hollow of a tree, where only they breed in communities, it is placed high

or low according to convenience. The fabric, which is very frail, now and then

gives way, either under the pressure of the parents and young, or during sudden

bursts of heavy rain, when the whole is dashed to the ground. The eggs are from

four to six, and of a pure white colour. Two broods are raised in the season.

The flight of this species is performed somewhat in the manner of the

European Swift, but in a more hurried although continued style, and generally by

repeated flappings, unless when courtship is going on, on which occasion it is

frequently seen sailing with its wings fixed as it were; both sexes as they

glide through the air issuing a shrill rattling twitter, and the female

receiving the caresses of the male. At other times it is seen ranging far and

wide at a considerable elevation over the forests and cities; again, in wet

weather, it flies close over the ground; and anon it skims the water, to drink

and bathe. When about to descend into a hollow tree or a chimney, its flight,

always rapid, is suddenly interrupted as if by magic, for down it goes in an

instant, whirling in a peculiar manner, and whirring with its wings, so as to

produce a sound in the chimney like the rumbling of very distant thunder. They

never alight on trees or on the ground. If one is caught and placed on the

latter, it can only move in a very awkward fashion. I believe that the old

birds sometimes fly at night, and have reason to think that the young are fed at

such times, as I have heard the whirring sound of the former, and the

acknowledging cries of the latter, during calm and clear nights.

When the young accidentally fall, which sometimes happens, although the

nest should remain, they scramble up again, by means of their sharp claws,

lifting one foot after another, in the manner of young Wood Ducks, and

supporting themselves with their tail. Some days before the young are able to

fly, they scramble up the walls to near the mouth of the chimney, where they are

fed. Any observer may discover this, as he sees the parents passing close over

them, without entering the funnel. The same occurrence takes place when they

are bred in a tree.

In the cities, these birds make choice of a particular chimney for their

roosting place, where, early in spring, before they have begun building, both

sexes resort in multitudes, from an hour or more before sunset, until long after

dark. Before entering the aperture, they fly round and over it many times, but

finally go in one at a time, until hurried by the lateness of the hour, several

drop in together. They cling to the wall with their claws, supporting

themselves also by their sharp tail, until the dawn, when, with a roaring sound,

the whole pass out almost at once. Whilst at St. Francisville in Louisiana, I

took the trouble of counting how many entered one chimney before dark. I sat at

a window not far from the spot, and reckoned upwards of a thousand, having

missed a considerable number. The place at that time contained about a hundred

houses, and no doubt existed in my mind that the greater number of these birds

were on their way southward, and had merely stopped there for the night.

Immediately after my arrival at Louisville, in the State of Kentucky, I

became acquainted with the late hospitable and amiable Major WILLIAM CROGHAN and

his family. While talking one day about birds, he asked me if I had seen the

trees in which the Swallows were supposed to spend the winter, but which they

only entered, he said, for the purpose of roosting. Answering in the

affirmative, I was informed that on my way back to town, there was a tree

remarkable on account of the immense numbers that resorted to it, and the place

in which it stood was described to me. I found it to be a sycamore, nearly

destitute of branches, sixty or seventy feet high, between seven and eight feet

in diameter at the base, and about five for the distance of forty feet up, where

the stump of a broken hollowed branch, about two feet in diameter, made out from

the main stem. This was the place at which the Swallows entered. On closely

examining the tree, I found it hard, but hollow to near the roots. It was now

about four o'clock, afternoon, in the month of July. Swallows were flying over

Jeffersonville, Louisville, and the woods around, but there were none near the

tree. I proceeded home, and shortly after returned on foot. The sun was going

down behind the Silver Hills; the evening was beautiful; thousands of Swallows

were flying closely above me, and three or four at a time were pitching into the

hole, like bees hurrying into their hive. I remained, my head leaning on the

tree, listening to the roaring noise made within by the birds as they settled

and arranged themselves, until it was quite dark, when I left the place,

although I was convinced that many more had to enter. I did not pretend to

count them, for the number was too great, and the birds rushed to the entrance

so thick as to baffle the attempt. I had scarcely returned to Louisville, when

a violent thunder-storm passed suddenly over the town, and its appearance made

me think that the hurry of the Swallows to enter the tree was caused by their

anxiety to avoid it. I thought of the Swallows almost the whole night, so

anxious had I become to ascertain their number, before the time of their

departure should arrive.

Next morning I rose early enough to reach the place long before the least

appearance of daylight, and placed my head against the tree. All was silent

within. I remained in that posture probably twenty minutes, when suddenly I

thought the great tree was giving way,, and coming down upon me. Instinctively

I sprung from it, but when I looked up to it again, what was my astonishment to

see it standing as firm as ever. The Swallows were now pouring out in a black

continued stream. I ran back to my post, and listened in amazement to the noise

within, which I could compare to nothing else than the sound of a large wheel

revolving under a powerful stream. It was yet dusky, so that I could hardly see

the hour on my watch, but I estimated the time which they took in getting out at

more than thirty minutes. After their departure, no noise was heard within, and

they dispersed in every direction with the quickness of thought.

I immediately formed the project of examining the interior of the tree,

which, as my kind friend, Major CROGHAN, had told me, proved the most remarkable

I had ever met with. This I did, in company with a hunting associate. We went

provided with a strong line and a rope, the first of which we, after several

trials, succeeded in throwing across the broken branch. Fastening the rope to

the line we drew it up, and pulled it over until it reached the ground again.

Provided with the longest cane we could find, I mounted the tree by the rope,

without accident, and at length seated myself at ease on the broken branch; but

my labour was fruitless, for I could see nothing through the hole, and the cane,

which was about fifteen feet long, touched nothing on the sides of the tree

within that could give any information. I came down fatigued and disappointed.

The next day I hired a man, who cut a hole at the base of the tree. The

shell was only eight or nine inches thick, and the axe soon brought the inside

to view, disclosing a matted mass of exuviae, with rotten feathers reduced to a

kind of mould, in which, however, I could perceive fragments of insects and

quills. I had a passage cleared, or rather bored through this mass, for nearly

six feet. This operation took up a good deal of time, and knowing by experience

that if the birds should notice the hole below. they would abandon the tree, I

had it carefully closed. The Swallows came as usual that night, and I did not

disturb them for several days. At last, provided with a dark lantern, I went

with my companion about nine in the evening, determined to have a full view of

the interior of the tree. The hole was opened with caution. I scrambled up the

sides of the mass of exuvia, and my friend followed. All was perfectly silent.

Slowly and gradually I brought the light of the lantern to bear on the sides of

the hole above us, when we saw the Swallows clinging side by side, covering the

whole surface of the excavation. In no instance did I see one above another.

Satisfied with the sight, I closed the lantern. We then caught and killed with

as much care as possible more than a hundred, stowing them away in our pockets

and bosoms, and slid down into the open air. We observed that, while on this

visit, not a bird had dropped its dung upon us. Closing the entrance, we

marched towards Louisville perfectly elated. On examining the birds which we

had procured, a hundred and fifteen in number, we found only six females.

Eighty-seven were adult males; of the remaining twenty-two the sex could not be

ascertained, and I had no doubt that they were the young of that year's first

brood, the flesh and quill-feathers being tender and soft.

Let us now make a rough calculation of the number that clung to the tree.

The space beginning at the pile of feathers and moulded exuviae, and ending at

the entrance of the hole above, might be fully 25 feet in height, with a breadth

of 15 feet, supposing the tree to be 5 feet in diameter at an average. There

would thus be 375 feet square of surface. Each square foot, allowing a bird to

cover a space of 3 inches by 1 1/2 which is more than enough, judging from the

manner in which they were packed, would contain 32 birds. The number of

Swallows, therefore, that roosted in this single tree was 9000.

I watched the motion of the Swallows, and when the young birds that had

been reared in the chimneys of Louisville, Jeffersonville, and the houses of the

neighbourhood, or the trees suited for the purpose, had left their native

recesses, I visited the tree on the 2nd day of August. I concluded that the

numbers resorting to it had not increased; but I found many more females and

young than males, among upwards of fifty, which were caught and opened. Day

after day I watched the tree. On the 13th of August, not more than two or three

hundred came there to roost. On the 18th of the same month, not one did I see

near it, and only a few scattered individuals were passing, as if moving

southward. In September I entered the tree at night, but not a bird was in it.

Once more I went to it in February, when the weather was very cold; and

perfectly satisfied that all these Swallows had left our country, I finally

closed the entrance, and left off visiting it.

May arrived, bringing with its vernal warmth the wanderers of the air, and

I saw their number daily augmenting, as they resorted to the tree to roost.

About the beginning of Sane, I took it in my head to close the aperture above,

with a bundle of straw, which with a string I could draw off whenever I might

choose. The result was curious enough; the birds as usual came to the tree

towards night; they assembled, passed and repassed, with apparent discomfort,

until I perceived many flying, off to a great distance, on which I removed the

straw, when many entered the hole, and continued to do so until I could no

longer see them from the ground.

I left Louisville, having removed my residence to Henderson, and did not

see the tree until five years after, when I still found the Swallows resorting

to it. The pieces of wood with which I had closed the entrance had rotted, or

had been carried off, and the hole was again completely filled with exuviae and

mould. During a severe storm, their ancient tenement at length gave way, and

came to the ground.

General WILLIAM CLARK assured me that he saw this species on the whole of

his route to the Pacific, and there can be no doubt that in those wilds it still

breeds in trees or rocky caverns.

Its food consists entirely of insects, the pellets composed of the

indigestible parts of which it disgorges. It is furnished with glands which

supply the unctuous matter with which it fastens its nest.

This species does not appear to extend its migrations farther east than the

British provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. It is unknown in

Newfoundland and Labrador; nor was it until the 29th of May that I saw some at

Eastport in Maine, where a few breed.

CHIMNEY SWALLOW, Hirundo pelasgia, Wils. Amer. Orn., vol. v. p. 48.

CYPSELUS PELASGIUS, Bonap. Syn., p. 63.

CHIMNEY SWIFT or SWALLOW, Cypselus pelasgius, Nutt. Man.,

vol. i. p. 609.

CHIMNEY SWALLOW or AMERICAN SWIFT, Cypselus pelasgius,

Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. ii. p. 329; vol. v. p. 419.

Brownish-black, lighter on the rump, with a slight greenish gloss on the

head and back; throat greyish-white, lower parts greyish-brown, tinged with

green; loral space black, and a greyish-white line over the eye. Female similar

to the male.

Male 4 1/4, 12.

| Next >> |