| Family VI. HIRUNDINAE. SWALLOWS. GENUS I. HIRUNDO, Linn. SWALLOW. |

Next >> |

Family |

THE BARN SWALLOW. [Barn Swallow.] |

| Genus | HIRUNDO RUSTICA, Linn. [Hirundo rustica.] |

The Barn Swallow makes its first appearance at New Orleans from the middle

of February to the first of March. They do not arrive in flocks, but apparently

in pairs, or a few together, and immediately resort to the places where they

have bred before, or where they have been reared. Their progress over the Union

depends much on the state of the weather; and I have observed a difference of a

whole month, owing to the varying temperature, in their arrival at different

places. Thus in Kentucky, Virginia, or Pennsylvania, they now and then do not

arrive until the middle of April or the beginning of May. In milder seasons

they reach Massachusetts and the eastern parts of Maine by the 10th of the

latter month, when you may rest assured that they are distributed over all the

intermediate districts. So hardy does this species seem to be, that I observed

it near Eastport in Maine, on the 7th May, 1833, in company with the Republican

or Cliff Swallow, pursuing its different avocations, while masses of ice hung

from every cliff, and the weather felt cold to me. I saw them in the Gut of

Cansso on the 10th of June, and on the Magdeleine Islands on the 13th of the

same month. They were occupied in building their nests in the open cupola of a

church. Not one, however, was observed in Labrador, although many Sand Martins

were seen there. On our return, I found at Newfoundland some of the present

species, and of the Cliff Swallow, all of which were migrating southward on the

14th of August, when Fahrenheit's thermometer stood at 41 degrees.

In spring, the Barn Swallow is welcomed by all, for she seldom appears

before the final melting of the snows and the commencement of mild weather, and

is looked upon as the harbinger of summer. As she never commits depredations on

any thing that men consider as their own, every body loves her, and, as the

child was taught by his parents, so the man teaches his offspring, to cherish

her. About a week after the arrival of this species, and when it has already

resorted to its wonted haunts, examined its last year's tenement, or made choice

of a place to which it may securely fix its nest, it begins either to build or

to deposit its eggs.

The nest is attached to the side of a beam or rafter in a barn or shed,

under a bridge, or sometimes even in an old well, or in a sink hole, such as

those found in the Kentucky barrens. Whenever the situation is convenient and

affords sufficient room, you find several nests together, and in some instances

I have seen seven or eight within a few inches of each other; nay, in some large

barns I have counted forty, fifty, or more. The male and the female both betake

themselves to the borders of creeks, rivers, ponds, or lakes, where they form

small pellets of mud or moist earth, which they carry in their bill to the

chosen spot, and place against the wood, the wall, or the rock, as it may chance

to be. They dispose of these pellets in regular lays, mixing, especially with

the lower, a considerable quantity of long slender grasses, which often dangle

for several inches beneath the bottom of the nest. The first layers are short,

but the rest gradually increase in length, as the birds proceed upwards with

their work, until they reach the top, when the fabric resembles the section of

an inverted cone, the length being eight inches, and the greatest diameter six,

while that from the wall or other flat surface to the outside of the shell is

three and a half, and the latter is fully an inch thick. I have never observed

in a newly finished nest, the expansion of the upper layer mentioned by WILSON,

although I have frequently seen it in one that has been repaired or enlarged.

The average weight of such a nest as I have described is more than two pounds,

but there is considerable difference as to size between different nests, some

being shorter by two or three inches, and proportionally narrow at the top.

These differences depend much on the time the birds have to construct their

tenement previous to depositing the eggs. Now and then I have seen some formed

at a late period, that were altogether destitute of the intermixture of grass

with the mud observed in the nest described above, which was a perfect one, and

had occupied the birds seven days in constructing it, during which period they

laboured from sunrise until dusk, with an intermission of several hours in the

middle of the day. Within the shell of mud is a bed, several inches thick, of

slender grasses arranged in a circular form, over which is placed a quantity of

large soft feathers. I never saw one of these nests in a chimney, nor have I

ever heard of their occurring in such situations, they being usually occupied by

the American Swift, which is a more powerful bird, and may perhaps prevent the

Barn Swallow from entering. The eggs are from four to six, rather small and

elongated, semi-translucent, white, and sparingly spotted all over with

reddish-brown. The period of incubation is thirteen days, and both sexes sit,

although not for the same length of time, the female performing the greater part

of the task. Each provides the other with food on this occasion, and both rest

at night beside each other in the nest. In South Carolina, where a few breed,

the nest is formed in the beginning of April, and in Kentucky about the first of

May.

When the young have attained a considerable size, the parents, who feed

them with much care and affection, roost in the nearest convenient place. This

species seldom raises more than two broods in the Southern and Middle Districts,

and never, I believe, more than one in Maine and farther north. The little

ones, when fully fledged, are enticed to fly by their parents, who, shortly

after their first essays, lead them to the sides of fields, roads or rivers,

where you may see them alight, often not far from each other, on low walls,

fence-stakes and twigs, or the withered twigs or branches of some convenient

tree, generally in the vicinity of a place in which the old birds can easily

procure food for them. As the young improve in flying, they are often fed on

the wing by the parent birds. On such occasions, when the old and young birds

meet, they both rise obliquely in the air, and come close together, when the

food is delivered in a moment, and they separate to continue their gambols. In

the evening the family retires to the breeding place, to which it usually

resorts until the period of their migration.

About the middle of August, the old and young birds form more extensive

associations, flying about in loose flocks, which are continually increasing,

and alighting in groups on tall trees, churches, court-houses, or barns, where

they may be seen for hours pluming and dressing themselves, or removing the

small insects which usually infest them. At such times they chirp almost

continually, and make sallies of a few hundred yards, returning to the same

place. These meetings and rambles often occupy a fortnight, but generally by

the 10th of September great flocks have set out for the south, while others are

seen arriving from the north. The dawn of a fair morning is the time usually

chosen by these birds for their general departure, which I have no reason to

believe is prevented by a contrary wind. They are seen moving off without

rising far above the tops of the trees or towns over which they pass; and I am

of opinion that most of them in large parties usually migrate either along the

shores of the Atlantic, or along the course of large streams, such places being

most likely to afford suitable retreats at night, when they betake themselves to

the reeds and other tall grasses, if it is convenient to do so, although I have

witnessed their migration during a fine, clear, quiet evening. Should they meet

with a suitable spot, they alight close together, and for awhile twitter loudly,

as if to invite approaching flocks or stragglers to join them. In such places I

have seen great flocks of this species in East Florida;--and here, reader, I may

tell you that the fogs of that latitude seem not unfrequently to bewilder their

whole phalanx. One morning, whilst on board the United States Schooner "Spark,"

lieutenant commandant PIERCY and the officers directed my attention to some

immense flocks of these birds flying only a few feet above the water for nearly

an hour, and moving round the vessel as if completely lost. But when the

morning is clear, these Swallows rise in a spiral manner from the reeds to the

height of thirty or forty yards, extend their ranks, and continue their course.

I found flocks of Barn Swallows near St. Augustine for several days in

succession, until the beginning of December; but after the first frost none were

to be seen. These could not have removed many decrees farther south, for want

of proper food, and I suspect that numbers of them spend the whole winter along

the south coast of the Gulf of Mexico.

The flight of this species is not less interesting than any other of its

characteristics. It probably surpasses in speed that of any other species of

the feathered tribes, excepting the Humming-bird. In fine calm weather their

circuits are performed at a considerable elevation, with a lightness and ease

that are truly admirable. They play over the river, the field, or the city with

equal grace, and during spring and summer you might imagine their object was to

fill the air around them with their cheerful twitterings. When the weather

lowers, they move more swiftly in tortuous meanderings over the meadows, and

through the streets of the towns; they pass and repass, now close to the

pavement, now along the walls of the buildings, here and there snapping an

insect as they glide along with a motion so rapid that you can scarcely follow

them with the eye. But try:--There she skims against the wind over the ruffled

stream; up she shoots, seizes an insect, and wheeling round, sails down the

breeze with a rapidity that carries her out of your sight almost in a moment.

Noon arrives, and the weather being sultry, round the horse or the cow she

passes a thousand times, seizing on each tormenting fly. Now she seems fain to

enter the wood, so close along its edge does she pursue her prey; but spying a

Crow, a Raven, a Hawk or an Eagle, off she shoots with redoubled speed after

the marauder, and the next instant is seen lambing, as it were, the object of

her anger with admirable dexterity, after which, full of gaiety and pride, the

tiny thing returns towards the earth, forming to herself a most tortuous path in

the air.

On the ground the movements of this Swallow are by no means awkward,

although, when compared with those of other birds, they seem rather hampered.

It walks by very short steps, and aids itself with its wings. Should it be

necessary to remove to the distance of a few yards, it prefers flying. When

alighted on a twig, it shews a peculiar tremulous motion of the wings and tail.

The song of our Barn Swallow resembles that of the Chimney Swallow of

England so much that I am unable to discern the smallest difference. Both sing

on the wing and when alighted, and the common tweet which they utter when flying

off is precisely the same in both. Their food also is similar; at least that of

our bird consists entirely of insects, some being small coleoptera, the

crustaceous parts of which are disgorged in roundish pellets scarcely the size

of a small pea.

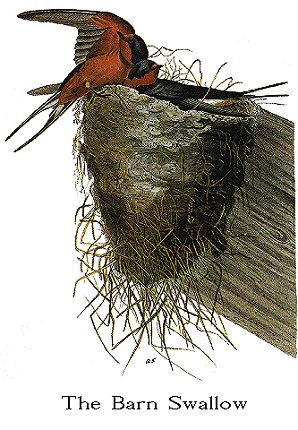

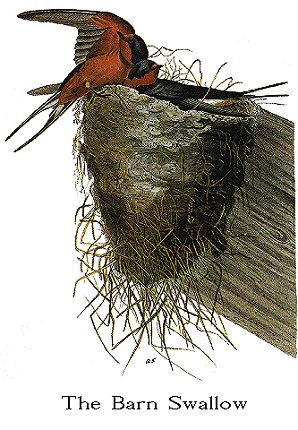

I have represented a pair of our Barn Swallows in the most perfect spring

plumage, together with a nest taken from one of the rafters of a barn in the

State of New Jersey, in which there was at least a score of them.

An individual of this species preserved in spirits measured to end of tail

6 8/12 inches, to end of wings 6 2/12; wing from flexure 4 10/12; tail 3 1/4;

extent of wings 12 9/12. The roof of the mouth is flat and somewhat

transparent; the posterior aperture of the nares oblongo-linear, margined with

strong papillae; the tongue 3 1/4 twelfths long, triangular, emarginate and

papillate at the base, thin, the tip slit and lacerate. The mouth is supplied

with numerous mucous crypts; its width is 5 1/2 twelfths. There is a very

narrow flattened salivary gland, similar to that of the Purple Martin, but

proportionally smaller. The oesophagus is 2 inches long, 1 1/2 twelfths in

width, simple or without dilatation. The stomach is elliptical, 7 1/2 twelfths

long, 6 twelfths broad, its muscles distinct; the epithelium, as in the other

species, tough, with longitudinal rugae, and of a reddish-brown colour. The

intestine is short and wide, its length being 6 1/2 inches, its breadth from

2 1/2 twelfths to 2 twelfths. The coeca are 2 twelfths long, twelfth wide, and

placed at the distance of 11 twelfths from the extremity; the rectum is dilated

into an oblong cloaca; about 5 twelfths in width.

The trachea is 1 inch 5 twelfths long, moderately flattened, from 1 twelfth

to 3/4 twelfth in breadth; its rings pretty firm, 50 in number, with two

dimidiate rings. The muscles are as in the other species; the bronchi are

moderate, of about 15 half rings.

BARN SWALLOW, Hirundo Americana, Wils. Amer. Orn., vol. v. p. 34.

HIRUNDO AMERICANA, AMERICAN BARN SWALLOW,

Swains. & Rich. F. Bor. Amer., vol. ii. p. 329.

HIRUNDO RUFA, Bonap. Syn., p. 64.

BARN SWALLOW, Hirundo rufa, Nutt. Man., vol. i. p. 601.

BARN SWALLOW, Hirundo rustica, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. ii. p. 413;

vol. v. p. 411.

Tail very deeply forked, the lateral feathers much exceeding the wings.

Forehead and throat bright chestnut; upper parts and a band on the fore-neck

glossy deep steel-blue; quills and tail brownish-black, glossed with green; the

latter with a white spot on the inner web of each of the feathers, except the

two middle. Female similar to the male. Young less deeply coloured, the

forehead and throat pale red, the band on the fore-neck dusky, tinged with red;

lateral tail-feathers not exceeding the wings.

Male, 7, 13. Female, 6 3/12, 12 9/12.

| Next >> |