| Family VII. MUSCICAPINAE. FLYCATCHERS. GENUS II. MUSCICAPA, Linn. FLYCATCHER. |

Next >> |

Family |

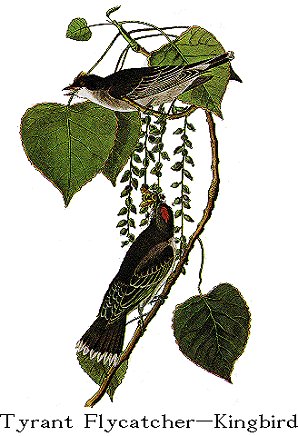

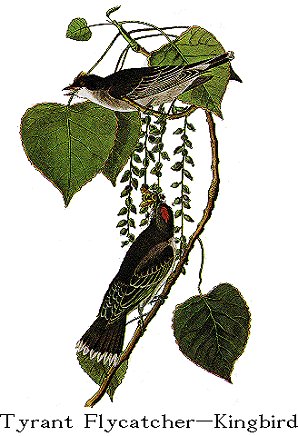

THE TYRANT FLYCATCHER.--KING-BIRD [Eastern Kingbird.] |

| Genus | MUSCICAPA TYRANNUS, Linn. [Tyrannus tyrannus.] |

The Tyrant Flycatcher, or, as it is commonly named, the Field Martin, or

King-bird, is one of the most interesting visiters of the United States, where

it is to be found during spring and summer, and where, were its good qualities

appreciated as they deserve to be, it would remain unmolested. But man being

generally disposed to consider in his subjects a single fault sufficient to

obliterate the remembrance of a thousand good qualites, even when the latter are

beneficial to his interest, and tend to promote his comfort, persecutes the

King-bird without mercy, and extends his enmity to its whole progeny. This

mortal hatred is occasioned by a propensity which the Tyrant Flycatcher now and

then shews to eat a honey-bee, which the farmer looks upon as exclusively his

own property.

The Field Martin arrives in Louisiana, from the south, about the middle of

March. Many individuals remain until the middle of September, but the greater

number proceed gradually northwards, and are dispersed over every portion of the

United States. For a few days after its arrival, it seems fatigued and doleful,

and remains perfectly silent. But no sooner has it recovered its naturally

lively spirits, than its sharp tremulous cry is heard over the fields, and along

the skirts of all our woods. It seldom enters the forests, but is fond of

orchards, large fields of clover, the neighbourhood of rivers, and the gardens

close to the houses of the planters. In this last situation its habits are best

observed.

Its flight has now assumed a different manner. The love-season is at hand.

The male and female are seen moving about through the air, with a continued

quivering motion of their wings, at a height of twenty or thirty yards above the

ground, uttering a continual, tremulous, loud shriek. The male follows in the

wake of the female, and both seem panting for a suitable place in which to form

their nest. Meanwhile, they watch the motions of different insects, deviate a

little from the course of their playful rounds, and with a sweeping dart secure

and swallow the prey in an instant. Probably the next sees them perched on the

twig of a tree, close together, and answering the calls Of nature.

The choice of a place being settled by the happy pair, they procure small

dry twigs from the ground, and rising to a horizontal branch, arrange them as

the foundation of their cherished home. Flakes of cotton, wool or tow, and

other substances of a similar nature, are then placed in thick and regular

layers, giving great bulk and consistence to the fabric, which is finally lined

with fibrous roots and horse-hair. The female then deposits her eggs, which are

from four to six in number, broadly ovate, reddish-white, or blush colour,

irregularly spotted with brown. No sooner has incubation commenced, than the

male, full of ardour, evinces the most daring courage, and gallantly drives off

every intruder. Perched on a twig not far from his beloved mate, in order to

protect and defend her, he seems to direct every thought and action to these

objects. His snow-white breast expands with the warmest feelings; the feathers

of his head are raised and spread, the bright orange spot laid open to the rays

of the sun; he stands firm on his feet, and his vigilant eye glances over the

wide field of vision around him. Should he espy a Crow, a Vulture, a Martin, or

an Eagle, in the neighbourhood or at a distance, he spreads his wing to the air,

and pressing towards the dangerous foe, approaches him, and commences his attack

with fury. He mounts above the enemy, sounds the charge, and repeatedly

plunging upon the very back of his more powerful antagonist, essays to secure a

hold. In this manner, harassing his less active foe with continued blows of his

bill, he follows him probably for a mile, when, satisfied that he has done his

duty, he gives his wings their usual quivering motion, and returns exulting and

elated to his nest, trilling his notes all the while.

Few Hawks will venture to approach the farm-yard while the King-bird is

near. Even the cat in a great measure remains at home; and, should she appear,

the little warrior, fearless as the boldest Eagle, plunges towards her, with

such rapid and violent motions, and so perplexes her with attempts to peck on

all sides, that grimalkin, ashamed of herself, returns discomfited to the house.

The many eggs of the poultry which he saves from the plundering Crow, the

many chickens that are reared under his protection, safe from the clutches of

the prowling Hawks, the vast number of insects which he devours, and which would

otherwise torment the cattle and horses, are benefits conferred by him, more

than sufficient to balance the few raspberries and figs which he eats, and

calculated to insure for him the favour and protection of man.

The King-bird fears none of his aerial enemies save the Martin; and

although the latter frequently aids him in protecting his nest, and watching

over the farm-yard, it sometimes attacks him with such animosity as to force him

to retreat, the flight of the Martin being so superior to that of the King-bird

in quickness and power, as to enable it to elude the blows which the superior

strength of the latter might render fatal. I knew an instance in which some

Martins, that had been sole proprietors of a farm-yard for several seasons,

shewed so strong an antipathy to a pair of King-birds, which had chanced to

build their nest on a tree within a few yards of the house, that, no sooner had

the female begun to sit on her eggs, than the Martin attacked the male with

unremitting violence for several days, and, notwithstanding his courage and

superior strength, repeatedly felled him to the ground, until he at length died

of fatigue, when the female was beaten off in a state of despair, and forced to

seek a new protector.

The King-bird is often seen passing on the wing over a field of clover,

diving down to the very blossoms, and reascending in graceful undulations,

snapping his bill, and securing various sorts of insects, now and then varying

his mode of chase in curious zigzag lines, shooting to the right and left, up

and down, as if the object which he is pursuing were manoeuvring for the purpose

of eluding him.

About the month of August, this species becomes comparatively mute, and

resorts to the old abandoned fields and meadows. There, perched on a

fence-stake or a tall mullein stalk, he glances his eye in various directions,

watching the passing insects, after which he darts with a more direct motion

than in spring. Having secured one, he returns to the same or another stalk,

beats the insect, and then swallows it. He frequently flies high over the large

rivers and lakes, sailing and dashing about in pursuit of insects. Again,

gliding down towards the water, he drinks in the manner of various species of

Swallow. When the weather is very warm, he plunges repeatedly into the water,

alights after each plunge on the low branch of a tree close by, shakes off the

water and plumes himself, when, perceiving some individuals of his tribe passing

high over head, he ascends to overtake them, and bidding adieu to the country,

proceeds towards a warmer region.

The King-bird leaves the Middle States earlier than most other species.

While migrating southwards, at the approach of winter, it flies with a strong

and continued motion, flapping its wings six or seven times pretty rapidly, and

sailing for a few yards without any undulations, at every cessation of the

flappings. On the first days of September, I have several times observed them

passing in this manner, in detached parties of twenty or thirty, perfectly

silent, and so resembling the Turdus migratorius in their mode of flight, as to

induce the looker-on to suppose them of that species, until he recognises them

by their inferior size. Their flight is continued through the night, and by the

1st of October none are to be found in the Middle States. The young acquire the

full colouring of their plumage before they leave us for the south.

The flesh of this bird is delicate and savoury. Many are shot along the

Mississippi, not because these birds eat bees, but because the French of

Louisiana are fond of bee-eaters. I have seen some of these birds that had the

shafts of the tail-feathers reaching a quarter of an inch beyond the end of the

webs.

This bold Flycatcher is not satisfied with ranging throughout the United

States, but extends its migrations across the continent to the Columbia river,

and, according to Dr. RICHARDSON, northward as far as the 57th parallel, where

it breeds, arriving in May, and departing in the beginning of September. I have

found it breeding in the Texas, on the one hand, in Labrador on the other, and

in all intervening districts, excepting the Florida Keys, where it is

represented by the Pipiry Flycatcher. I have never seen it dive after fish, or

even after aquatic insects, although. as I have already mentioned, it throws

itself into the water for the purpose of bathing; nor have remains of fishes

been found in its stomach or gullet. Like all Flycatchers, it disgorges the

harder parts of insects.

How wonderful is it that this bird should be found breeding over so vast an

extent of country, and yet retire southward of the Texas, to spend a very short

part of the winter! Some, however, remain then in the southern portions of the

Floridas. The eggs measure rather more than an inch in length, and six and a

half eighths in breadth; they are broadly rounded at the larger end, the other

being suddenly brought to a sharpish conical point.

This bird has the mouth wide, the palate flat, with two longitudinal

ridges, its anterior part horny, and concave, with a median and two slight

lateral prominent lines; the posterior aperture of the nares oblongo-linear,

papillate, 4 1/2 twelfths long. The tongue is six-twelfths long, triangular,

very thin, sagittate and papillate at the base, flat above, pointed, but a

little slit, and with the edges slightly lacerated. The oesophagus is 2 1/2

inches long, without dilatation, of the uniform width of 3 twelfths, and

extremely thin; the proventriculus 3 1/2 twelfths across. The stomach is rather

large, broadly elliptical, considerably compressed; its lateral muscles strong,

the lower thin, its length 10 twelfths, its breadth 8 twelfths, its tendons

4 1/2 twelfths in breadth; the epithelium thin, tough, longitudinally rugous,

reddish-brown. The stomach filled with remains of insects. The intestine is

short and wide, 7 inches long, its width at the upper part 4 twelfths, at the

lower 2 twelfths. The coeca are 2 twelfths long, 1/2 twelfth in breadth, and

placed at an inch and a half from the extremity. The rectum gradually dilates

into the cloaca, which is 6 twelfths in width.

The trachea is 2 inches 2 twelfths long, considerably flattened, 2 1/2

twelfths broad at the upper part, gradually contracting to 1 1/4 twelfths; its

rings 56, firm, with 2 dimidiate rings. It is remarkable that in this and the

other Flycatchers, there is no bone of divarication, or ring divided by a

partition; but two of the rings are slit behind, and the last two both behind

and before. Bronchial rings about 15. The lateral muscles are slender, but at

the lower part expand so as to cover the front of the trachea, and running down,

terminate on the dimidiate rings, so that on each side of the inferior larynx

there is a short thick mass of muscular fibres, which are scarcely capable of

being divided into distinct portions, although three pairs may be in some degree

traced, an anterior, a middle, and a posterior. These muscles are similarly

formed in all the other birds of this family the Muscicapinae, described in this

work.

LANIUS TYRANNUS, Linn. Syst. Nat., vol. i. p. 136.

TYRANT FLYCATCHER, Muscicapa tyrannus, Wils. Amer. Orn.,

vol. i. p. 66.

MUSCICAPA TYRANNUS, Bonap. Syn., p. 66.

KING-BIRD or TYRANT FLYCATCHER, Muscicapa tyrannus, Nutt. Man.,

vol. i. p. 265.

TYRANT FLYCATCHER, Muscicapa tyrannus, Aud. Orn. Biog.,

vol. i. p. 403; vol. v. p. 420.

The outer two primaries attenuated at the end, the second longest, the

first longer than the third; tail even. Upper parts dark bluish-grey; the head

greyish-black, with a bright vermilion patch margined with yellow; quills,

coverts, and tail feathers brownish-black, the former margined with dull white,

the latter largely tipped with white; lower parts greyish-white; the breast pale

grey. Female duller; the upper parts tinged with brown; the lower more dusky.

Male, 8 1/2, 14 1/2.

North America generally. Migratory. A few winter in the south of

Florida.

THE COTTON-WOOD.

POPULUS CANDICANS, Willd., Sp. Pl., vol. iv. p. 806. Pursch., Fl. Amer.,

vol. ii. p. 618. Mich., Arbr. Forest. de l'Amer. Sept., vol. iii.

pl. 13.--DIOECIA OCTANDRIA, Linn.--AMENTACEAE, Juss.

This species of Poplar is distinguished by its broadly cordate, acuminate,

unequally and obtusely serrated venous leaves, hairy petioles, resinous buds,

and round twigs. The leaves are dark green above, whitish beneath. The

resinous substance with which the buds are covered has an agreeable smell. The

bark is smooth, of a greenish tint.

| Next >> |