| Family VII. MUSCICAPINAE. FLYCATCHERS. GENUS II. MUSCICAPA, Linn. FLYCATCHER. |

Next >> |

Family |

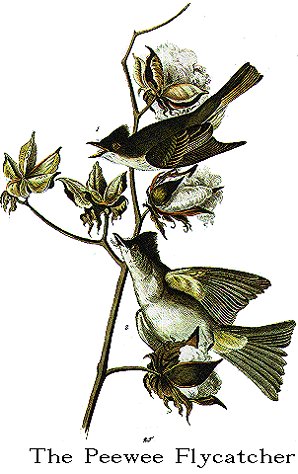

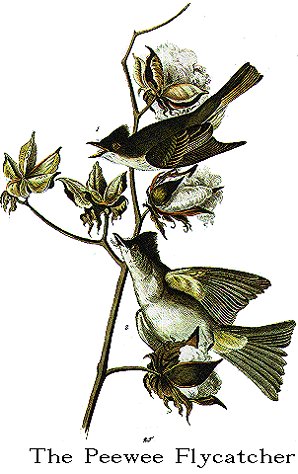

THE PEWEE FLYCATCHER. [Eastern Phoebe.] |

| Genus | MUSCICAPA FUSCA, Gmel. [Sayornis phoebe.] |

Connected with the biography of this bird are so many incidents relative to

my own, that could I with propriety deviate from my proposed method, the present

number would contain less of the habits of birds than of those of the youthful

days of an American woodsman. While young, I had a plantation that lay on the

sloping declivities of the Perkiomen creek. I was extremely fond of rambling

along its rocky banks, for it would have been difficult to do so either without

meeting with a sweet flower, spreading open its beauties to the sun, or

observing the watchful King-fisher perched on some projecting stone over the

clear water of the stream. Nay, now and then, the Fish Hawk itself, followed by

a White-headed Eagle, would make his appearance, and by his graceful aerial

motions, raise my thoughts far above them into the heavens, silently leading me

to the admiration of the sublime Creator of all. These impressive, and always

delightful, reveries often accompanied my steps to the entrance of a small cave

scooped out of the solid rock by the band of nature. It was, I then thought,

quite large enough for my study. My paper and pencils, with now and then a

volume of EDGEWORTH's natural and fascinating Tales or LAFONTAINE's Fables,

afforded me ample pleasures. It was in that place, kind reader, that I first

saw with advantage the force of parental affection in birds. There it was that

I studied the habits of the Pewee; and there I was taught most forcibly, that to

destroy the nest of a bird, or to deprive it of its eggs or young, is an act of

great cruelty.

I had observed the nest of this plain-coloured Flycatcher fastened, as it

were, to the rock immediately over the arched entrance of this calm retreat. I

had peeped into it: although empty, it was yet clean, as if the absent owner

intended to revisit it with the return of spring. The buds were already much

swelled, and some of the trees were ornamented with blossoms, yet the ground was

still partially covered with snow, and the air retained the piercing chill of

winter. I chanced one morning early to go to my retreat. The sun's glowing

rays gave a rich colouring to every object around. As I entered the cave, a

rustling sound over my head attracted my attention, and, on turning, I saw two

birds fly off, and alight on a tree close by:--the Pewees had arrived! I felt

delighted, and fearing that my sudden appearance might disturb the gentle pair,

I walked off; not, however, without frequently looking at them. I concluded

that they must have just come, for they seemed fatigued:--their plaintive note

was not heard, their crests were not erected, and the vibration of the tail, so

very conspicuous in this species, appeared to be wanting in power. Insects were

yet few, and the return of the birds looked to me as prompted more by their

affection to the place, than by any other motive. No sooner had I gone a few

steps than the Pewees, with one accord, glided down from their perches and

entered the cave. I did not return to it any more that day, and as I saw none

about it, or in the neighbourhood, I supposed that they must have spent the day

within it. I concluded also that these birds must have reached this haven,

either during the night, or at the very dawn of that morn. Hundreds of

observations have since proved to me that this species always migrates by night.

I went early next morning to the cave, yet not early enough to surprise

them in it. Long before I reached the spot, my ears were agreeably saluted by

their well-known note, and I saw them darting about through the air, giving

chase to some insects close over the water. They were full of gaiety,

frequently flew into and out of the cave, and while alighted on a favourite tree

near it, seemed engaged in the most interesting converse. The light fluttering

or tremulous motions of their wings, the jetting of their tail, the erection of

their crest, and the neatness of their attitudes, all indicated that they were,

no longer fatigued, but on the contrary refreshed and happy. On my going into

the cave, the male flew violently towards the entrance, snapped his bill sharply

and repeatedly, accompanying this action with a tremulous rolling note, the

import of which I soon guessed. Presently he flew into the cave and out of it

again, with a swiftness scarcely credible: it was like the passing of a shadow.

Several days in succession I went to the spot, and saw with pleasure that

as my visits increased in frequency, the birds became more familiarized to me,

and, before a week had elapsed, the Pewees and myself were quite on terms of

intimacy. It was now the 10th of April; the spring was forward that season, no

more snow was to be seen, Redwings and Grakles were to be found here and there.

The Pewees, I observed, began working at their old nest. Desirous of judging

for myself, and anxious to enjoy the company of this friendly pair, I determined

to spend the greater part of each day in the cave. My presence no longer

alarmed either of them. They brought a few fresh materials, lined the nest

anew, and rendered it warm by adding a few large soft feathers of the common

goose, which they found strewn along the edge of the water in the creek. There

was a remarkable and curious twittering in their note while both sat on the edge

of the nest at those meetings, and which is never heard on any other occasion.

It was the soft, tender expression, I thought, of the pleasure they both

appeared to anticipate of the future. Their mutual caresses, simple as they

might have seemed to another, and the delicate manner used by the male to please

his mate, rivetted my eyes on these birds, and excited sensations which I can

never forget.

The female one day spent the greater part of the time in her nest; she

frequently changed her position; her mate exhibited much uneasiness, he would

alight by her sometimes, sit by her side for a moment, and suddenly flying out,

would return with an insect, which she took from his bill with apparent

gratification. About three o'clock in the afternoon, I saw the uneasiness of

the female increase; the male showed an unusual appearance of despondence, when,

of a sudden, the female rose on her feet, looked sidewise under her, and flying

out, followed by her attentive consort, left the cave, rose high in the air,

performing evolutions more curious to me than any I had seen before. They flew

about over the water, the female leading her mate, as it were, through her own

meanderings. Leaving the Pewees to their avocations, I peeped into their nest,

and saw there their first egg, so white and so transparent--for I believe,

reader, that eggs soon loose this peculiar transparency after being laid--that

to me the sight was more pleasant than if I had met with a diamond of the same

size. The knowledge that in an enclosure so frail, life already existed, and

that ere many weeks would elapse, a weak, delicate, and helpless creature, but

perfect in all its parts, would burst the shell, and immediately call for the

most tender care and attention of its anxious parents, filled my mind with as

much wonder as when, looking towards the heavens, I searched, alas! in vain,

for the true import of all that I saw.

In six days, six eggs were deposited; but I observed that as they increased

in number, the bird remained a shorter time in the nest. The last she deposited

in a few minutes after alighting. Perhaps, thought I, this is a law of nature,

intended for keeping the eggs fresh to the last. About an hour after laying the

last egg, the female Pewee returned, settled in her nest, and, after arranging

the eggs, as I thought, several times under her body, expanded her wings a

little, and fairly commenced the arduous task of incubation.

Day after day passed by. I gave strict orders that no one should go near

the cave, much less enter it, or indeed destroy any bird's nest on the

plantation. Whenever I visited the Pewees, one or other of them was on the

nest, while its mate was either searching for food, or perched in the vicinity,

filling the air with its loudest notes. I not unfrequently reached out my hand

near the sitting bird; and so gentle had they both become, or rather so well

acquainted were we, that neither moved on such occasions, even when my hand was

quite close to it. Now and then the female would shrink back into the nest, but

the male frequently snapped at my fingers, and once left the nest as if in great

anger, flew round the cave a few times, emitting his querulous whining notes,

and alighted again to resume his labours.

At this very time, a Pewee's nest was attached to one of the rafters of my

mill, and there was another under a shed in the cattle-yard. Each pair, any one

would have felt assured, had laid out the limits of its own domain, and it was

seldom that one trespassed on the grounds of its neighbour. The Pewee of the

cave generally fed or spent its time so far above the mill on the creek, that he

of the mill never came in contact with it. The Pewee of the cattle-yard

confined himself to the orchard, and never disturbed the rest. Yet I sometimes

could hear distinctly the notes of the three at the same moment. I had at that

period an idea that the whole of these birds were descended from the same stock.

If not correct in this supposition, I had ample proof afterwards that the brood

of young Pewees, raised in the cave, returned the following spring, and

established themselves farther up on the creek, and among the outhouses in the

neighbourhood.

On some other occasion, I will give you such instances of the return of

birds, accompanied by their progeny, to the place of their nativity, that

perhaps you will become convinced, as I am at this moment, that to this

propensity every country owes the augmentation of new species, whether of birds

or of quadrupeds, attracted by the many benefits met with, as countries become

more open and better cultivated: but now I will, with your leave, return to the

Pewees of the cave.

On the thirteenth day, the little ones were hatched. One egg was

unproductive, and the female, on the second day after the birth of her brood,

very deliberately pushed it out of the nest. On examining this egg, I found it

contained the embryo of a bird partly dried up, with its vertebrae quite fast to

the shell, which had probably occasioned its death. Never have I since so

closely witnessed the attention of birds to their young. Their entrance with

insects was so frequently repeated, that I thought I saw the little ones grow as

I razed upon them. The old birds no longer looked upon me as an enemy, and

would often come in close by me, as if I had been a post. I now took upon me to

handle the young frequently; nay, several times I took the whole family out, and

blew off the exuviae of the feathers from the nest. I attached Light threads to

their legs: these they invariably removed, either with their bills, or with the

assistance of their parents. I renewed them, however, until I found the little

fellows habituated to them; and at last, when they were about to leave the nest,

I fixed a light silver thread to the le, of each, loose enough not to hurt the

part, but so fastened that no exertions of theirs could remove it.

Sixteen days had passed, when the brood took to wing; and the old birds,

dividing the time with caution, began to arrange the nest anew. A second set of

eggs were laid, and in the beginning of August a new brood made its appearance.

The young birds took much to the woods, as if feeling themselves more

secure there than in the open fields; but before they departed, they all

appeared strong, and minded not making long sorties into the open air, over the

whole creek, and the fields around it. On the 8th of October, not a Pewee could

I find on the plantation: my little companions had all set off on their

travels. For weeks afterwards, however, I saw Pewees arriving from the north,

and lingering a short time, as if to rest, when they also moved southward.

At the season when the Pewee returns to Pennsylvania, I had the

satisfaction to observe those of the cave in and about it. There again, in the

very same nest, two broods were raised. I found several Pewees nests at some

distance up the creek, particularly under a bridge, and several others in the

adjoining meadows, attached to the inner parts of sheds erected for the

protection of hay and grain. Having caught several of these birds on the nest,

I had the pleasure of finding that two of them had the little ring on the leg.

I was now obliged to go to France, where I remained two years. On my

return, which happened early in August, I had the satisfaction of finding three

young Pewees in the nest of the cave; but it was hot the nest which I had left

in it. The old one had been torn off from the roof, and the one which I found

there was placed above where it stood. I observed at once that one of the

parent birds was as shy as possible, while the other allowed me to approach

within a few yards. This was the male bird, and I felt confident that the old

female had paid the debt of nature. Having inquired of the miller's son, I

found that he had killed the old Pewee and four young ones, to make bait for the

purpose of catching fish. Then the male Pewee had brought another female to the

cave! As long as the plantation of Mill Grove belonged to me, there continued

to be a Pewee's nest in my favourite retreat; but after I had sold it, the cave

was destroyed, as were nearly all the beautiful rocks along the shores of the

creek, to build a new dam across the Perkiomen.

This species is so peculiarly fond of attaching its nest to rocky caves,

that, were it called the Rock Flycatcher, it would be appropriately named.

Indeed I have seldom passed near such a place, particularly during the breeding

season, without seeing the Pewee, or hearing its notes. I recollect that, while

travelling in Virginia with a friend, he desired. that I would go somewhat out

of our intended route, to visit the renowned Rock Bridge of that State. My

companion, who had passed over this natural bridge before, proposed a wager that

he could lead me across it before I should be aware of its existence. It was

early in April; and, from the descriptions of this place which I had read, I

felt confident that the Pewee Flycatcher must be about it. I accepted the

proposal of my friend and trotted on, intent on proving to myself that, by

constantly attending to one subject, a person must sooner or later become

acquainted with it. I listened to the notes of the different birds, which at

intervals came to my ear, and at last had the satisfaction to distinguish those

of the Pewee. I stopped my horse, to judge of the distance at which the bird

might be, and a moment after told my friend that the bridge was short of a

hundred yards from us, although it was impossible for us to see the spot itself.

The surprise of my companion was great. "How do you know this?" he asked,

"for," continued he, "you are correct."--"Simply," answered I, "because I hear

the notes of the Pewee, and know that a cave, or a deep rocky creek, is at

hand." We moved on; the Pewees rose from under the bridge in numbers; I pointed

to the spot and won the wager.

This rule of observation I have almost always found to work, as

arithmeticians say, both ways. Thus the nature of the woods or place in which

the observer may be, whether high or low, moist or dry, sloping north or south,

with whatever kind of vegetation, tall trees of particular species, or low

shrubs, will generally disclose the nature of their inhabitants.

The flight of the Pewee Flycatcher is performed by a fluttering light

motion, frequently interrupted by sailings. It is slow when the bird is

proceeding to some distance, rather rapid when in pursuit of prey. It often

mounts perpendicularly from its perch after an insect, and returns to some dry

twig, from which it can see around to a considerable distance. It then swallows

the insect whole, unless it happens to be large. It will at times pursue an

insect to a considerable distance, and seldom without success. It alights with

great firmness, immediately erects itself in the manner of Hawks, glances all

around, shakes its wings with a tremulous motion, and vibrates its tail upwards

as if by a spring. Its tufty crest is generally erected, and its whole

appearance is neat, if not elegant. The Pewee has its particular stands, from

which it seldom rambles far. The top of a fence stake near the road is often

selected by it, from which it sweeps off in all directions, returning at

intervals, and thus remaining the greater part of the morning and evening. The

corner of the roof of the barn suits it equally well, and if the weather

requires it, it may be seen perched on the highest dead twig of a tall tree.

During the heat of the day it reposes in the shade of the woods. In the autumn

it will choose the stalk of the mullein for its stand, and sometimes the

projecting, angle of a rock jutting over a stream. It now and then alights on

the ground for an instant, but this happens principally during winter, or while

engaged during spring in collecting the materials of which its nest is composed,

in our Southern States, where many spend their time at this season.

I have found this species abundant in the Floridas in winter, in full song,

and as lively as ever, also in Louisiana and the Carolinas, particularly in the

cotton fields. None, however, to my knowledge, breed south of Charleston in

South Carolina, and very few in the lower parts of that State. They leave

Louisiana in February, and return to it in October. Occasionally during winter

they feed on berries of different kinds, and are quite expert at discovering the

insects impaled on thorns by the Loggerhead Shrike, and which they devour with

avidity. I met with a few of these birds on the Magdeleine Islands, on the

coast of Labrador, and in Newfoundland.

The nest of this species bears some resemblance to that of the Barn

Swallow, the outside consisting of mud, with which are firmly impacted grasses

or mosses of various kinds deposited in regular strata. It is lined with

delicate fibrous roots, or shreds of vine bark, wool, horse-hair, and sometimes

a few feathers. The greatest diameter across the open mouth is from five to six

inches, and the depth from four to five. Both birds work alternately, bringing

pellets of mud or damp earth, mixed with moss, the latter of which is mostly

disposed on the outer parts, and in some instances the whole exterior looks as

if entirely formed of it. The fabric is firmly attached to a rock, or a wall,

the rafter of a house, &c. In the barrens of Kentucky I have found the nests

fixed to the side of those curious places called sinkholes, and as much as

twenty feet below the surface of the ground. I have observed that when the

Pewees return in spring, they strengthen their tenement by adding to the

external parts attached to the rock, as if to prevent it from falling, which

after all it sometimes does when several years old. Instances of their taking

possession of the nest of the Republican Swallow (Hirundo fulva) have been

observed in the State of Maine. The eggs are from four to six, rather

elongated, pure white, generally with a few reddish spots near the larger end.

In Virginia, and probably as far as New York, they not unfrequently raise

two broods, sometimes three, in a season.

This species ejects the hard particles of the wings, legs, abdomen, and

other parts of insects, in small pellets, in the manner of Owls, Goatsuckers and

Swallows.

The following characters presented by the digestive organs and trachea, are

common to all the North American small Flycatchers, varying only in their

relative dimensions. The roof of the mouth is flat and somewhat diaphanous; its

anterior part with three prominent lines, the palate with longitudinal ridges;

the posterior aperture of the nares linear-oblong, margined with papillae. The

tongue is 4 1/2 twelfths long, rather broad, very thin, emarginate and papillate

at the base, the tip slit. The mouth is rather wide, measuring 4 3/4 twelfths

across. There is a very narrow oblong, salivary gland in the usual place, and

opening by three ducts. The oesophagus is 2 inches 1 twelfth long, 2 1/2

twelfths wide, without dilatation. The stomach is rather small, 6 twelfths

long, 5 twelfths broad, considerably compressed, the lateral muscles distinct

aDd of moderate size, the lower very thin; the epithelium thin, tough,

longitudinally rugous, brownish-red. The stomach filled with insects. The

intestine is 6 1/2 inches long, from 1 3/4 twelfths to 1 twelfth in width; the

coeca 1 1/2 twelfths long, 1/2 twelfth broad 1 inch distant from the extremity;

the rectum gradually dilates into an ovate cloaca.

The trachea is 1 inch 7 twelfths long, from 1 twelfth to 3/4 twelfth in

breadth, considerably flattened; the rings 78, with two additional dimidiate

rings. The bronchi are of moderate length, with 12 half rings. The lateral

muscles are very slender, as are the sterno-tracheales; the inferior laryngeal

are very small, and seem to form only a single pair.

PEWIT FLYCATCHER, Muscicapa nunciola, Wils. Amer. Orn.,

vol. ii. p. 78.

MUSCICAPA FUSCA, Bonap. Syn., p. 68.

PEWIT FLYCATCHER or PHOEBE, Nutt. Man., vol. i. p. 278.

PEWEE FLYCATCHER, Muscicapa fusca, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. ii. p. 122;

vol. v. p. 424.

Wing much rounded, third quill longest, fourth scarcely shorter, but

considerably longer than second, first intermediate between sixth and seventh;

tail emarginate; upper parts dull olive, the head much darker; quills and tail

dusky brown, secondaries and their coverts edged with pale brown; outer

tail-feathers whitish on the outer edge, unless toward the tip, lower parts dull

yellowish-white, the breast tinged with grey.

Male, 7, 9 1/2.

Throughout the United States, and northward. Spends the winter in vast

numbers in the southern parts.

THE COTTON PLANT.

GOSSYPIUM HERBACEUM, Linn., Syst. Nat., vol. ii. p. 462.

--MONADELPHIA POLYANDRIA, Linn.--MALVACEAE, Juss.

This species, commonly known in America, is distinguished by its five-lobed

leaves and herbaceous stem.

| Next >> |