As early as 4000 - 5000 BCE humans, first in the Sinai region of Egypt, and a millennium later in Mesoamerica and China, were mining and working turquoise into jewelry and ceremonial objects. It was so highly valued in Eqypt, that when high quality deposits were exhausted, artisans developed a copper glazed ceramic simulant called faience, rather than abandon use of that sky blue color in their artwork.

Chemically, turquoise is a hydrated copper/aluminum phosphate, of aggregate, cryptocrystalline structure. There is only one known deposit (in the state of Virginia) where turquoise is found in transparent to translucent discrete visible crystals. Specimens from that locale are rare and bring a hefty price from collectors.

More typically, turquoise is found as an opaque deposit in nodules, or veins within host rocks, or as shallow crusts on the surface of rocks.

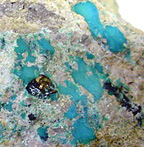

Color ranges through shades of blue to blue-green to yellowish green depending on the amount of copper (adds blue) chromium or vanadium (adds green) and iron (adds yellow). There are rare specimens of blue-violet color which contain strontium impurities. In general, US mines produce slightly greenish blue, to green gems due to high iron and vanadium content. Most turquoise rough contains patches or veins of the host rock in which it formed, such as chalcedony or opal, brown limonite, black chert or white kaolinite.

Such matrix can affect the color and toughness of the stone and its workability for the lapidary or jeweler. Relatively pure specimens of turquoise might have a hardness of around 5 and be moderately porous. In general, a high proportion of silicate minerals increases hardness and decreases porosity while a high content of clay minerals (like kaolinite) has the opposite effect. On one end of this spectrum, then, we find pieces of hardness 5.5 to 6 that take a bright polish and are minimally porous, and on the other end are pieces of a soft and chalky nature with so much porosity as to be unusable without stabilization.

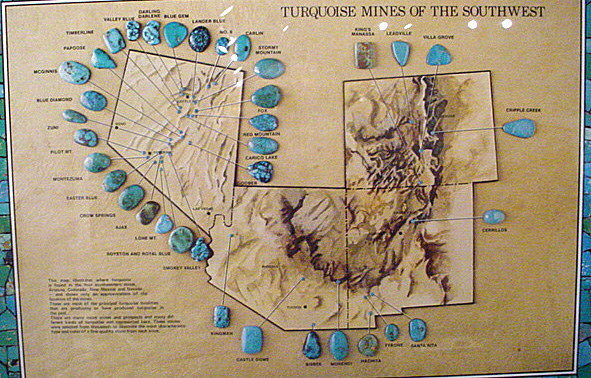

Turquoise occurs, usually in arid regions, where ground water percolates through aluminous rock in the vicinity of copper deposits. Like malachite, then, it is a secondary mineral which forms through the interaction of pre-existing minerals and their solutions. Historically the finest material was obtained from mines in Persia (Iran), and there is still considerable production from that area, but the majority of today's commerce in turquoise is supported primarily by sites in North America, and China. Its name, from French, means "Turkish stone", a reference to the long history of imports of Persian material, through Turkey, to the West.

The US deposits are almost exclusively limited to the Southwest with Nevada home to a larger number of mines than Arizona, New Mexico and Colorado put together. This is a source of pride for Nevada and turquoise is, in fact, its official State Mineral.

Historically, and to a large extent today, the most admired stones are those of a fine robin's egg or celestial blue color with no visible matrix (this shade is an indication that no iron and little vanadium is present). Historically, stones of this caliber were produced only in Persia (Iran), and some still are, but the world's supply is now supplemented by similar stones primarily from the US, such as those obtained from the Sleeping Beauty Mine near Globe, Arizona. It is common in the gem marketplace to call any pure blue, high quality material "Persian grade" regardless of its actual geographic origin.

In the Middle East it has been traditional to set turquoise in gold, sometimes with diamonds. The Victorians also greatly admired turquoise, and generally set it in gold as well. In the US, though, turquoise has had a long historical association with silver jewelry.

Long before the arrival of Europeans in North American, the native inhabitants had an appreciation for turquoise, which is still strong today. The significance of this gem for some tribal groups rivals the importance that the ancient Chinese gave to nephrite jade. Such was also true in South America, and the early Spanish invaders recorded their surprise in finding turquoise to be more highly valued by the native people than was gold.

During the 1960's and 70's there was a burst of admiration for turquoise among the US population, especially as found in Native American jewelry. After reaching the heights for a few years, this fad crashed amidst scandals involving simulants, imitations and "Indian" jewelry (even that being sold by some Native Americans ) which was made in Asia.

The popularity of this gem is now once again at stratospheric levels, due to a combination of some well known modern designers favoring the stone, and aggressive promotion by home shopping channels and fashion magazines. Although still widely available in traditional silver Southwestern style pieces, more and more designers are emulating the ancient Persians and the Victorians and setting pieces in gold.

The highest grades of turquoise are used for cabochons, carvings, and inlay, with the lesser grades finding use as polished beads or natural "nugget-style" beads.

Among those who prefer the look of turquoise with visible matrix, the highest regard is generally given to material with an even, interconnected patterning of black matrix veins. Stones of this type are referred to a "spiderweb" turquoise.

There are numerous enhancements and simulants in the marketplace. All but the highest grades of turquoise may be "stabilized" by a pressure infusion of wax or resin. Small, porous pieces are sometimes pressed together with a resin binder to make a stabilized mosaic. Although it is usually true that Chinese turquoise has softer matrix, and tends to be more porous than that from much of the American Southwest, the photos below show, stabilization or lack of it is not always obvious and it's dangerous to generalize.

A relatively new electro-chemical enhancement called the "Zachary Process" has recently been promoted as an alternative to traditional stabilization, and is said to increase both durability and evenness of color. Some large retailers are now marketing gems treated in this way under proprietary brand names.

Turquoise itself is infrequently dyed, but the white and grey-veined mineral, Howlite, accepts dye readily and is commonly found for sale. Unfortunately not all the dyed Howlite offered is properly labeled as "faux" turquoise. Howlite is sometimes sold in its natural state with the misnomer "white turquoise" --> but, make no mistake about it, there is NO such thing as white turquoise!

In addition, there are numerous non-mineral imitations such as plastic, ceramic and glass, offered with or without matrix. Synthetic turquoise is also available, the most well known type of which was first produced by the Gilson company in 1972.

A recent import from China, which is being sold as "yellow turquoise" (almost exclusively as beads) has been featured at some shows and by some retailers. The natural color is actually a light yellow-green, indicating high iron and low copper content, but, buyer beware, as some very bright sunshine or butter yellow dyed pieces are being offered without much effort to discriminate them from the unenchanced material.

About the only natural gem with which turquoise is likely to be confused is variscite (which lacks copper), and which can look similar to green turquoise. Variscite and turquoise, in fact, sometimes occur together in a rock which has been dubbed "variquoise" which brings a premium price for its attractive patterns and combinations of colors.

As a gem material, turquoise has its limitations: it is relatively fragile, porous, and susceptible to heat and/or chemical damage. Turquoise averages 18 - 20% water content, and as the gem is heated (perhaps from an unwary jeweler's torch) that water is progressively lost until at 400 degrees C, the structural integrity of the mineral is destroyed.

Few deposits of material are of such a fine grained and compact nature that they take a good polish and have low porosity. For these reasons, the majority of turquoise found in commerce today has been enhanced in one way or another. Even top grade, otherwise natural, stones are often given a surface coat of paraffin wax to seal them and enhance the polish. (Skin oils and cosmetic residues are prime culprits in changing and darkening the color of turquoise gems.)

Due to this stone's properties, it is best to make turquoise rings and bracelets occasional wear items, and to protect all turquoise jewelry from heat, chemicals and shocks. So, no ultrasonic or steam cleaning, and wash only with mild, lukewarm soapy water and a soft brush, and wipe pieces with a damp cloth after wearing.

There is an avid collector market for turquoise, with sibling rivalry amongst the various enthusiasts who see virtue in different colors, matrix variations and mine sites. Just as no gem collection would be complete without several representatives of this species, so no jewelry collection should be without at least one piece featuring this well beloved December birthstone gem.

Evenness and saturation of color,

would be the most important consideration in terms of value, followed

closely by the degree to which the material is compact and capable of

taking a good polish without stabilization. Among those who

appreciate matrix patterns, the beauty of that pattern would be

crucial in setting value. In my opinion, turquoise is a real gem

bargain, for even the very highest grades of material are modestly

priced compared to many other gems.