The Student’s Elements of Geology

Recent and Post-pliocene Periods. — Terms defined. — Formations of the Recent Period. — Modern littoral Deposits containing Works of Art near Naples. — Danish Peat and Shell-mounds. — Swiss Lake-dwellings. — Periods of Stone, Bronze, and Iron. — Post-pliocene Formations. — Coexistence of Man with extinct Mammalia. — Reindeer Period of South of France. — Alluvial Deposits of Paleolithic Age. — Higher and Lower-level Valley-gravels. — Loess or Inundation-mud of the Nile, Rhine, etc. — Origin of Caverns. — Remains of Man and extinct Quadrupeds in Cavern Deposits. — Cave of Kirkdale. — Australian Cave-breccias. — Geographical Relationship of the Provinces of living Vertebrata and those of extinct Post-pliocene Species. — Extinct struthious Birds of New Zealand. — Climate of the Post-pliocene Period. — Comparative Longevity of Species in the Mammalia and Testacea. — Teeth of Recent and Post-pliocene Mammalia.

We have seen in the last chapter that the uppermost or newest strata are called Post-tertiary, as being more modern than the Tertiary. It will also be observed that the Post-tertiary formations are divided into two subordinate groups: the Recent, and Post-pliocene. In the former, or the Recent, the mammalia as well as the shells are identical with species now living: whereas in the Post-pliocene, the shells being all of living forms, a part, and often a considerable part, of the mammalia belonged to extinct species. To this nomenclature it may be objected that the term Post-pliocene should in strictness include all geological monuments posterior in date to the Pliocene; but when I have occasion to speak of the whole collectively, I shall call them Post-tertiary, and reserve the term Post-pliocene for the older Post-tertiary formations, while the Upper or newer ones will be called “Recent.”

Cases will occur where it may be scarcely possible to draw the boundary line between the Recent and Post-pliocene deposits; and we must expect these difficulties to increase rather than diminish with every advance in our knowledge, and in proportion as gaps are filled up in the series of records.

It was stated in the sixth chapter, when I treated of denudation, that the dry land, or that part of the earth’s surface which is not covered by the waters of lakes or seas, is

generally wasting away by the incessant action of rain and rivers, and in some cases by the undermining and removing power of waves and tides on the sea-coast. But the rate of waste is very unequal, since the level and gently sloping lands, where they are protected by a continuous covering of vegetation, escape nearly all wear and tear, so that they may remain for ages in a stationary condition, while the removal of matter is constantly widening and deepening the intervening ravines and valleys.

The materials, both fine and coarse, carried down annually by rivers from the higher regions to the lower, and deposited in successive strata in the basins of seas and lakes, must be of enormous volume. We are always liable to underrate their magnitude, because the accumulation of strata is going on out of sight.

There are, however, causes at work which, in the course of centuries, tend to render visible these modern formations, whether of marine or lacustrine origin. For a large portion of the earth’s crust is always undergoing a change of level, some areas rising and others sinking at the rate of a few inches, or a few feet, perhaps sometimes yards, in a century; so that spaces which were once subaqueous are gradually converted into land, and others which were high and dry become submerged. In consequence of such movements we find in certain regions, as in Cashmere, for example, where the mountains are often shaken by earthquakes, deposits which were formed in lakes in the historical period, but through which rivers have now cut deep and wide channels. In lacustrine strata thus intersected, works of art and fresh-water shells are seen. In other districts on the borders of the sea, usually at very moderate elevations above its level, raised beaches occur, or marine littoral deposits, such as those in which, on the borders of the Bay of Baiæ, near Naples, the well-known temple of Serapis was imbedded. In that case the date of the monument buried in the marine strata is ascertainable, but in many other instances the exact age of the remains of human workmanship is uncertain, as in the estuary of the Clyde at Glasgow, where many canoes have been exhumed, with other works of art, all assignable to some part of the Recent Period.

Danish Peat and Shell-mounds or Kitchen-middens.—Sometimes we obtain evidence, without the aid of a change of level, of events which took place in pre-historic times. The combined labours, for example, of the antiquary, zoologist, and botanist have brought to light many monuments of the early inhabitants buried in peat-mosses in Denmark. Their

geological age is determined by the fact that, not only the contemporaneous fresh-water and land shells, but all the quadrupeds, found in the peat, agree specifically with those now inhabiting the same districts, or which are known to have been indigenous in Denmark within the memory of man. In the lower beds of peat (a deposit varying from 20 to 30 feet in thickness), weapons of stone accompany trunks of the Scotch fir, Pinus sylvestris. This peat may be referred to that part of the stone period for which Sir John Lubbock proposed the name of “Neolithic”* in contradistinction to a still older era, termed by him “Paleolithic,” and which will be described in the sequel. In the higher portions of the same Danish bogs, bronze implements are associated with trunks and acorns of the common oak. It appears that the pine has never been a native of Denmark in historical times, and it seems to have given place to the oak about the time when articles and instruments of bronze superseded those of stone. It also appears that, at a still later period, the oak itself became scarce, and was nearly supplanted by the beech, a tree which now flourishes luxuriantly in Denmark. Again, at the still later epoch when the beech-tree abounded, tools of iron were introduced, and were gradually substituted for those of bronze.

On the coasts of the Danish islands in the Baltic, certain mounds, called in those countries “Kjökken-mödding,” or “kitchen-middens,” occur, consisting chiefly of the castaway shells of the oyster, cockle, periwinkle, and other eatable kinds of molluscs. The mounds are from three to ten feet high, and from 100 to 1000 feet in their longest diameter. They greatly resemble heaps of shells formed by the Red Indians of North America along the eastern shores of the United States. In the old refuse-heaps, recently studied by the Danish antiquaries and naturalists with great skill and diligence, no implements of metal have ever been detected. All the knives, hatchets, and other tools, are of stone, horn, bone, or wood. With them are often intermixed fragments of rude pottery, charcoal and cinders, and the bones of quadrupeds on which the rude people fed. These bones belong to wild species still living in Europe, though some of them, like the beaver, have long been extirpated in Denmark. The only animal which they seem to have domesticated was the dog.

As there is an entire absence of metallic tools, these refuse-heaps are referred to the Neolithic division of the age of stone, which immediately preceded in Denmark the age of

* Sir John Lubbock, Pre-historic Times, p. 3, 1865.

bronze. It appears that a race more advanced in civilisation, armed with weapons of that mixed metal, invaded Scandinavia, and ousted the aborigines.

Lacustrine Habitations of Switzerland.—In Switzerland a different class of monuments, illustrating the successive ages of stone, bronze, and iron, has been of late years investigated with great success, and especially since 1854, in which year Dr. F. Keller explored near the shore at Meilen, in the bottom of the lake of Zurich, the ruins of an old village, originally built on numerous wooden piles, driven, at some unknown period, into the muddy bed of the lake. Since then a great many other localities, more than a hundred and fifty in all, have been detected of similar pile-dwellings, situated near the borders of the Swiss lakes, at points where the depth of water does not exceed 15 feet.* The superficial mud in such cases is filled with various articles, many hundreds of them being often dredged up from a very limited area. Thousands of piles, decayed at their upper extremities, are often met with still firmly fixed in the mud.

As the ages of stone, bronze, and iron merely indicate successive stages of civilisation, they may all have coexisted at once in different parts of the globe, and even in contiguous regions, among nations having little intercourse with each other. To make out, therefore, a distinct chronological series of monuments is only possible when our observations are confined to a limited district, such as Switzerland.

The relative antiquity of the pile-dwellings, which belong respectively to the ages of stone and bronze, is clearly illustrated by the associations of the tools with certain groups of animal remains. Where the tools are of stone, the castaway bones which served for the food of the ancient people are those of deer, the wild boar, and wild ox, which abounded when society was in the hunter state. But the bones of the later or bronze epoch were chiefly those of the domestic ox, goat, and pig, indicating progress in civilisation. Some villages of the stone age are of later date than others, and exhibit signs of an improved state of the arts. Among their relics are discovered carbonised grains of wheat and barley, and pieces of bread, proving that the cultivation of cereals had begun. In the same settlements, also, cloth, made of woven flax and straw, has been detected.

The pottery of the bronze age in Switzerland is of a finer texture, and more elegant in form, than that of the age of stone. At Nidau, on the lake of Bienne, articles of iron have

* Bulletin de la Sociétié Vaudoise des Sci. Nat., tome vi, Lausanne 1860; and Antiquity of Man, by the author, chap. ii.

also been discovered, so that this settlement was evidently not abandoned till that metal had come into use.

At La Thène, in the northern angle of the lake of Neufchâtel, a great many articles of iron have been obtained, which in form and ornamentation are entirely different both from those of the bronze period and from those used by the Romans. Gaulish and Celtic coins have also been found there by MM. Schwab and Desor. They agree in character with remains, including many iron swords, which have been found at Tiefenau, near Berne, in ground supposed to have been a battle-field; and their date appears to have been anterior to the great Roman invasion of Northern Europe, though perhaps not long before that event.* Coins, which sometimes occur in deposits of the age of iron, have never yet been found in formations of the ages of bronze or stone.

The period of bronze must have been one of foreign commerce, as tin, which enters into this metallic mixture in the proportion of about ten per cent to the copper, was obtained by the ancients chiefly from Cornwall.† Very few human bones of the bronze period have been met with in the Danish peat, or in the Swiss lake-dwellings, and this scarcity is generally attributed by archæologists to the custom of burning the dead, which prevailed in the age of bronze.

From the foregoing observations we may infer that the ages of iron and bronze in Northern and Central Europe were preceded by a stone age, the Neolithic, referable to that division of the post-tertiary epoch which I have called Recent, when the mammalia as well as the other organic remains accompanying the stone implements were of living species. But memorials have of late been brought to light of a still older age of stone, for which, as above stated, the name Paleolithic has been proposed, when man was contemporary in Europe with the elephant and rhinoceros, and various other animals, of which many of the most conspicuous have long since died out.

Reindeer Period in South of France.—In the larger number of the caves of Europe, as for example in those of England, Belgium, Germany, and many parts of France, the animal remains agree specifically with the fauna of this oldest division of the age of stone, or that to which belongs the drift of Amiens and Abbeville presently to be mentioned, containing

* Sir J. Lubbock’s Lecture, Royal Institution, Feb. 27th, 1863.

† Diodorus, v, 21, 22 and Sir H. James Note on Block of Tin dredged up in Falmouth Harbour. Royal Institution of Cornwall, 1863.

flint implements of a very antique type. But there are some caves in the departments of Dordogne, Aude, and other parts of the south of France, which are believed by M. Lartet to be of intermediate date between the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods. To this intermediate era M. Lartet gave, in 1863, the name of the “reindeer period,” because vast quantities of the bones and horns of that deer have been met with in the French caverns. In some cases separate plates of molars of the mammoth, and several teeth of the great Irish deer, Cervus megaceros, and of the cave-lion, Felis spelæa, have been found mixed up with cut and carved bones of reindeer. On one of these sculptured bones in the cave of Perigord, a rude representation of the mammoth, with its long curved tusks and covering of wool, occurs, which is regarded by M. Lartet as placing beyond all doubt the fact that the early inhabitants of these caves must have seen this species of elephant still living in France. The presence of the marmot, as well as the reindeer and some other northern animals, in these caverns seems to imply a colder climate than that of the Swiss lake-dwellings, in which no remains of reindeer have as yet been discovered. The absence of this last in the old lacustrine habitations of Switzerland is the more significant, because in a cave in the neighbourhood of the lake of Geneva, namely, that of Mont Saleve, bones of the reindeer occur with flint implements similar to those of the caverns of Dordogne and Perigord.

The state of the arts, as exemplified by the instruments found in these caverns of the reindeer period, is somewhat more advanced than that which characterises the tools of the Amiens drift, but is nevertheless more rude than that of the Swiss lake-dwellings. No metallic articles occur, and the stone hatchets are not ground after the fashion of celts; the needles of bone are shaped in a workmanlike style, having their eyes drilled with consummate skill.

The formations above alluded to, which are as yet but imperfectly known, may be classed as belonging to the close of the Paleolithic era, of the monuments of which I am now about to treat.

Alluvial Deposits of the Paleolithic Age.—The alluvial and marine deposits of the Paleolithic age, the earliest to which any vestiges of man have yet been traced back, belong to a time when the physical geography of Europe differed in a marked degree from that now prevailing. In the Neolithic period, the valleys and rivers coincided almost entirely with those by which the present drainage of the land is effected, and the peat-mosses were the same as those now growing.

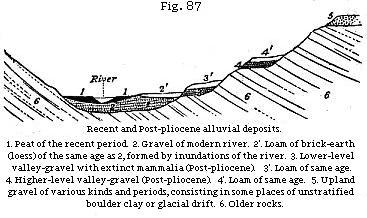

The situation of the shell-mounds and lake-dwellings above alluded to is such as to imply that the topography of the districts where they are observed has not subsequently undergone any material alteration. Whereas we no sooner examine the Post-pliocene formations, in which the remains of so many extinct mammalia are found, than we at once perceive a more decided discrepancy between the former and present outline of the surface. Since those deposits originated, changes of considerable magnitude have been effected in the depth and width of many valleys, as also in the direction of the superficial and subterranean drainage, and, as is manifest near the sea-coast, in the relative position of land and water. In Fig. 87 an ideal section is given, illustrating the different position which the Recent and Post-pliocene alluvial deposits occupy in many European valleys.

The peat, No. 1, has been formed in a low part of the modern alluvial plain, in parts of which gravel No. 2 of the recent period is seen. Over this gravel the loam or fine sediment 2' has in many places been deposited by the river during floods which covered nearly the whole alluvial plain.

No. 3 represents an older alluvium, composed of sand and gravel, formed before the valley had been excavated to its present depth. It contains the remains of fluviatile shells of living species associated with the bones of mammalia, in part of recent, and in part of extinct species. Among the latter, the mammoth (E. primigenius) and the Siberian rhinoceros (R. tichorhinus) are the most common in Europe. No. 3' is a remnant of the loam or brick-earth by which No. 3 was overspread. No. 4 is a still older and more elevated terrace, similar in its composition and organic remains to No. 3, and covered in like manner with its inundation-mud,

4'. Sometimes the valley-gravels of older date are entirely missing, or there is only one, and occasionally there are more than two, marking as many successive stages in the excavation of the valley. They usually occur at heights varying from 10 to 100 feet, sometimes on the right and sometimes on the left side of the existing river-plain, but rarely in great strength on exactly opposite sides of the valley.

Among the genera of extinct quadrupeds most frequently met with in England, France, Germany, and other parts of Europe, are the elephant, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, horse, great Irish deer, bear, tiger, and hyæna. In the peat, No. 1 (Fig. 87), and in the more modern gravel and silt (No. 2), works of art of the ages of iron and bronze, and of the later or Neolithic stone period, already described, are met with. In the more ancient or Paleolithic gravels, 3 and 4, there have been found of late years in several valleys in France and England—as, for example, in those of the Seine and Somme, and of the Thames and Ouse, near Bedford—stone implements of a rude type, showing that man coexisted in those districts with the mammoth and other extinct quadrupeds of the genera above enumerated. In 1847, M. Boucher de Perthes observed in an ancient alluvium at Abbeville, in Picardy, the bones of extinct mammalia associated in such a manner with flint implements of a rude type as to lead him to infer that both the organic remains and the works of art were referable to one and the same period. This inference was soon after confirmed by Mr. Prestwich, who found in 1859 a flint tool in situ in the same stratum at Amiens that contained the remains of extinct mammalia.

The flint implements found at Abbeville and Amiens are most of them considered to be hatchets and spear-heads, and are different from those commonly called “celts.” These celts, so often found in the recent formations, have a more regular oblong shape, the result of grinding, by which also a sharp edge has been given to them. The Abbeville tools found in gravel at different levels, as in Nos. 3 and 4, Fig. 87, in which bones of the elephant, rhinoceros, and other extinct mammalia occur, are always unground, having evidently been brought into their present form simply by the chipping off of fragments of flint by repeated blows, such as could be given by a stone hammer.

Some of them are oval, others of a spear-headed form, no two exactly alike, and yet the greater number of each kind are obviously fashioned after the same general pattern. Their outer surface is often white, the original black flint having been discoloured and bleached by exposure to the air,

or by the action of acids, as they lay in the gravel. They are most commonly stained of the same ochreous colour as the flints of the gravel in which they are imbedded. Occasionally their antiquity is indicated not only by their colour but by superficial incrustations of carbonate of lime, or by dendrites formed of oxide of iron and manganese. The edges also of most of them are worn, sometimes by having been used as tools, or sometimes by having been rolled in the old river’s bed. They are met with not only in the lower-level gravels, as in No. 3, Fig. 87, but also in No. 4, or the higher gravels, as at St. Acheul, in the suburbs of Amiens, where the old alluvium lies at an elevation of about 100 feet above the level of the river Somme. At both levels fluviatile and land-shells are met with in the loam as well as in the gravel, but there are no marine shells associated, except at Abbeville, in the lowest part of the gravel, near the sea, and a few feet only above the present high-water mark. Here with fossil shells of living species are mingled the bones of Elephas primigenius and E. antiquus, Rhinoceros tichorhinus, Hippopotamus, Felis spelæa, Hyæna spelæa, reindeer, and many others, the bones accompanying the flint implements in such a manner as to show that both were buried in the old alluvium at the same period.

Nearly the entire skeleton of a rhinoceros was found at one point, namely, in the Menchecourt drift at Abbeville, the bones being in such juxtaposition as to show that the cartilage must have held them together at the time of their inhumation.

The general absence here and elsewhere of human bones from gravel and sand in which flint tools are discovered, may in some degree be due to the present limited extent of our researches. But it may also be presumed that when a hunter population, always scanty in numbers, ranged over this region, they were too wary to allow themselves to be overtaken by the floods which swept away many herbivorous animals from the low river-plains where they may have been pasturing or sleeping. Beasts of prey prowling about the same alluvial flats in search of food may also have been surprised more readily than the human tenant of the same region, to whom the signs of a coming tempest were better known.

Inundation-mud of Rivers.—Brick-earth.—Fluviatile Loam, or Loess.—As a general rule, the fluviatile alluvia of different ages (Nos. 2, 3, 4, Fig. 87) are severally made up of coarse materials in their lower portions, and of fine silt or loam in their upper parts. For rivers are constantly shifting their

position in the valley-plain, encroaching gradually on one bank, near which there is deep water, and deserting the other or opposite side, where the channel is growing shallower, being destined eventually to be converted into land. Where the current runs strongest, coarse gravel is swept along, and where its velocity is slackened, first sand, and then only the finest mud, is thrown down. A thin film of this fine sediment is spread, during floods, over a wide area, on one, or sometimes on both sides, of the main stream, often reaching as far as the base of the bluffs or higher grounds which bound the valley. Of such a description are the well-known annual deposits of the Nile, to which Egypt owes its fertility. So thin are they, that the aggregate amount accumulated in a century is said rarely to exceed five inches, although in the course of thousands of years it has attained a vast thickness, the bottom not having been reached by borings extending to a depth of 60 feet towards the central parts of the valley. Everywhere it consists of the same homogeneous mud, destitute of stratification—the only signs of successive accumulation being where the Nile has silted up its channel, or where the blown sands of the Libyan desert have invaded the plain, and give rise to alternate layers of sand and mud.

In European river-loams we occasionally observe isolated pebbles and angular pieces of stone which have been floated by ice to the places where they now occur; but no such coarse materials are met with in the plains of Egypt.

In some parts of the valley of the Rhine the accumulation of similar loam, called in Germany “loess,” has taken place on an enormous scale. Its colour is yellowish-grey, and very homogeneous; and Professor Bischoff has ascertained, by analysis, that it agrees in composition with the mud of the Nile. Although for the most part unstratified, it betrays in some places marks of stratification, especially where it contains calcareous concretions, or in its lower part where it rests on subjacent gravel and sand which alternate with each other near the junction. About a sixth part of the whole mass is composed of carbonate of lime, and there is usually an intermixture of fine quartzose and micaceous sand.

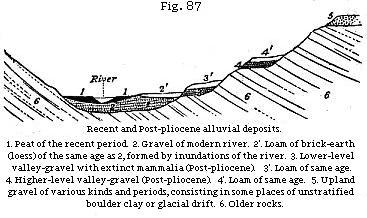

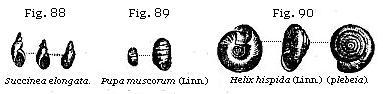

Although this loam of the Rhine is unsolidified, it usually terminates where it has been undermined by running water in a vertical cliff, from the face of which shells of terrestrial, fresh-water and amphibious mollusks project in relief. These shells do not imply the permanent sojourn of a body of fresh water on the spot, for the most aquatic of them, the Succinea,

inhabits marshes and wet grassy meadows. The Succinea elongata (or S. oblongata), Fig. 88, is very characteristic both of the loess of the Rhine and of some other European river-loams.

Among the land-shells of the Rhenish loess, Helix hispida, Fig. 90, and Pupa muscorum, Fig. 89, are very common. Both the terrestrial and aquatic shells are of most fragile and delicate structure, and yet they are almost invariably perfect and uninjured. They must have been broken to pieces had they been swept along by a violent inundation. Even the colour of some of the land-shells, as that of Helix nemoralis, is occasionally preserved.

In parts of the valley of the Rhine, between Bingen and Basle, the fluviatile loam or loess now under consideration is several hundred feet thick, and contains here and there throughout that thickness land and amphibious shells. As it is seen in masses fringing both sides of the great plain, and as occasionally remnants of it occur in the centre of the valley, forming hills several hundred feet in height, it seems necessary to suppose, first, a time when it slowly accumulated; and secondly, a later period, when large portions of it were removed, or when the original valley, which had been partially filled up with it, was re-excavated.

Such changes may have been brought about by a great movement of oscillation, consisting first of a general depression of the land, and then of a gradual re-elevation of the same. The amount of continental depression which first took place in the interior, must be imagined to have exceeded that of the region near the sea, in which case the higher part of the great valley would have its alluvial plain gradually raised by an accumulation of sediment, which would only cease when the subsidence of the land was at an end. If the direction of the movement was then reversed, and, during the re-elevation of the continent, the inland region nearest the mountains should rise more rapidly than that near the coast, the river would acquire a denuding power sufficient to enable it to sweep away gradually nearly all the loam and gravel with which parts of its basin had been filled up. Terraces and hillocks of mud and sand would then alone remain to attest the various levels at which

the river had thrown down and afterwards removed alluvial matter.

Cavern Deposits containing Human Remains and Bones of Extinct Animals.—In England, and in almost all countries where limestone rocks abound, caverns are found, usually consisting of cavities of large dimensions, connected together by low, narrow, and sometimes torturous galleries or tunnels. These subterranean vaults are usually filled in part with mud, pebbles, and breccia, in which bones occur belonging to the same assemblage of animals as those characterising the Post-pliocene alluvia above described. Some of these bones are referable to extinct and others to living species, and they are occasionally intermingled, as in the valley-gravels, with implements of one or other of the great divisions of the stone age, and these are not unfrequently accompanied by human bones, which are much more common in cavern deposits than in valley-alluvium.

Each suite of caverns, and the passages by which they communicate the one with the other, afford memorials to the geologist of successive phases through which they must have passed. First, there was a period when the carbonate of lime was carried out gradually by springs; secondly, an era when engulfed rivers or occasional floods swept organic and inorganic debris into the subterranean hollows previously formed; and thirdly, there were such changes in the configuration of the region as caused the engulfed rivers to be turned into new channels, and springs to be dried up, after which the cave-mud, breccia, gravel, and fossil bones would bear the same kind of relation to the existing drainage of the country as the older valley-drifts with their extinct mammalian remains and works of art bear to the present rivers and alluvial plains.

The quarrying away of large masses of Carboniferous and Devonian limestone, near Liege, in Belgium, has afforded the geologist magnificent sections of some of these caverns, and the former communication of cavities in the interior of the rocks with the old surface of the country by means of vertical or oblique fissures, has been demonstrated in places where it would not otherwise have been suspected, so completely have the upper extremities of these fissures been concealed by superficial drift, while their lower ends, which extended into the roofs of the caves, are masked by stalactitic incrustations.

The origin of the stalactite is thus explained by the eminent chemist Liebig. Mould or humus, being acted on by moisture and air, evolves carbonic acid, which is dissolved

by rain. The rain-water, thus impregnated, permeates the porous limestone, dissolves a portion of it, and afterwards, when the excess of carbonic acid evaporates in the caverns, parts with the calcareous matter, and forms stalactite. Even while caverns are still liable to be occasionally flooded such calcareous incrustations accumulate, but it is generally when they are no longer in the line of drainage that a solid floor of hard stalagmite is formed on the bottom.

The late Dr. Schmerling examined forty caves near Liege, and found in all of them the remains of the same fauna, comprising the mammoth, tichorhine rhinoceros, cave-bear, cave-hyæna, cave-lion, and many others, some of extinct and some of living species, and in all of them flint implements. In four or five caves only parts of human skeletons were met with, comprising sometimes skulls with a few other bones, sometimes nearly every part of the skeleton except the skull. In one of the caves, that of Engihoul, where Schmerling had found the remains of at least three human individuals, they were mingled in such a manner with bones of extinct mammalia, as to leave no doubt on his mind (in 1833) of man having co-existed with them.

In 1860, Professor Malaise, of Liege, explored with me this same cave of Engihoul, and beneath a hard floor of stalagmite we found mud full of bones of extinct and recent animals, such as Schmerling had described, and my companion, persevering in his researches after I had returned to England, extracted from the same deposit two human lower jaw-bones retaining their teeth. The skulls from these Belgian caverns display no marked deviation from the normal European type of the present day.

The careful investigations carried on by Dr. Falconer, Mr. Pengelly, and others, in the Brixham cave near Torquay, in 1858, demonstrated that flint knives were there imbedded in such a manner in loam underlying a floor of stalagmite as to prove that man had been an inhabitant of that region when the cave-bear and other members of the ancient post-pliocene fauna were also in existence.

The absence of gnawed bones had led Dr. Schmerling to infer that none of the Belgian caves which he explored had served as the dens of wild beasts; but there are many caves in Germany and England which have certainly been so inhabited, especially by the extinct hyæna and bear.

A fine example of a hyæna’s den was afforded by the cave of Kirkdale, so well described by the late Dr. Buckland in his Reliquiæ Diluvianæ. In that cave, above twenty-five miles north-north-east of York, the remains of about 300 hyænas,

belonging to individuals of every age, were detected. The species (Hyæna spelæa) has been considered by palæontologists as extinct; it was larger than the fierce Hyæna crocuta of South Africa, which it closely resembled, and of which it is regarded by Mr. Boyd Dawkins as a variety. Dr. Buckland, after carefully examining the spot, proved that the hyænas must have lived there; a fact attested by the quantity of their dung, which, as in the case of the living hyæna, is of nearly the same composition as bone, and almost as durable. In the cave were found the remains of the ox, young elephant, hippopotamus, rhinoceros, horse, bear, wolf, hare, water-rat, and several birds. All the bones have the appearance of having been broken and gnawed by the teeth of the hyænas; and they occur confusedly mixed in loam or mud, or dispersed through a crust of stalagmite which covers it. In these and many other cases it is supposed that portions of herbivorous quadrupeds have been dragged into caverns by beasts of prey, and have served as their food—an opinion quite consistent with the known habits of the living hyæna.

Australian Cave-breccias.—Ossiferous breccias are not confined to Europe, but occur in all parts of the globe; and those discovered in fissures and caverns in Australia correspond closely in character with what has been called the bony breccia of the Mediterranean, in which the fragments of bone and rock are firmly bound together by a red ochreous cement.

Some of these caves were examined by the late Sir T. Mitchell in the Wellington Valley, about 210 miles west of

Sidney, on the river Bell, one of the principal sources of the Macquarie, and on the Macquarie itself. The caverns often branch off in different directions through the rock, widening and contracting their dimensions, and the roofs and floors are covered with stalactite. The bones are often broken, but do not seem to be water-worn. In some places they lie imbedded in loose earth, but they are usually included in a breccia.

The remains belong to marsupial animals. Among the most abundant are those of the kangaroo, of which there are four species, while others belong to the genera Phascolomys, the wombat; Dasyurus), the ursine opossum; Phalangista, the vulpine opossum; and Hypsiprymnus, the kangaroo-rat.

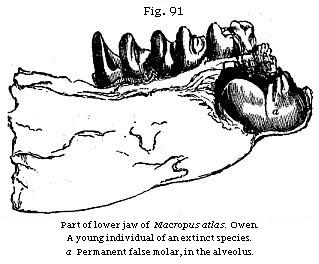

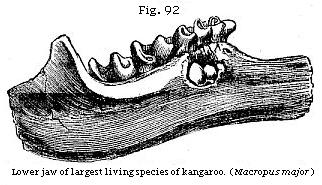

In the fossils above enumerated, several species are larger than the largest living ones of the same genera now known in Australia. Fig. 91 of the right side of a lower jaw of a kangaroo (Macropus atlas, Owen) will at once be seen to exceed in magnitude the corresponding part of the largest living kangaroo, which is represented in Fig. 92. In both these specimens part of the substance of the jaw has been broken open, so as to show the permanent false molar (a, Fig. 91), concealed in the socket. From the fact of this molar not having been cut, we learn that the individual was young, and had not shed its first teeth.

The reader will observe that all these extinct quadrupeds of Australia belong to the marsupial family, or, in other words, that they are referable to the same peculiar type of organisation which now distinguishes the Australian mammalia from those of other parts of the globe. This fact is one of many pointing to a general law deducible from the fossil vertebrate and invertebrate animals of times immediately antecedent to our own, namely, that the present geographical distribution of organic forms dates back to a period anterior to the origin of existing species; in other words,

the limitation of particular genera or families of quadrupeds, mollusca, etc., to certain existing provinces of land and sea, began before the larger part of the species now contemporary with man had been introduced into the earth.

Professor Owen, in his excellent “History of British Fossil Mammals,” has called attention to this law, remarking that the fossil quadrupeds of Europe and Asia differ from those of Australia or South America. We do not find, for example, in the Europæo-Asiatic province fossil kangaroos, or armadillos, but the elephant, rhinoceros, horse, bear, hyæna, beaver, hare, mole, and others, which still characterise the same continent.

In like manner, in the Pampas of South America the skeletons of Megatherium, Megalonyx, Glyptodon, Mylodon, Toxodon, Macrauchenia, and other extinct forms, are analogous to the living sloth, armadillo, cavy, capybara, and llama. The fossil quadrumana, also associated with some of these forms in the Brazilian caves, belong to the Platyrrhine family of monkeys, now peculiar to South America. That the extinct fauna of Buenos Ayres and Brazil was very modern has been shown by its relation to deposits of marine shells, agreeing with those now inhabiting the Atlantic.

The law of geographical relationship above alluded to, between the living vertebrata of every great zoological province and the fossils of the period immediately antecedent, even where the fossil species are extinct, is by no means confined to the mammalia. New Zealand, when first examined by Europeans, was found to contain no indigenous land quadrupeds, no kangaroos, or opossums, like Australia; but a wingless bird abounded there, the smallest living representative of the ostrich family, called the Kiwi by the natives (Apteryx). In the fossils of the Post-pliocene period in this same island, there is the like absence of kangaroos, opossums, wombats, and the rest; but in their place a prodigious number of well-preserved specimens of gigantic birds of the struthious order, called by Owen Dinornis and Palapteryx, which are entombed in superficial deposits. These genera comprehended many species, some of which were four, some seven, others nine, and others eleven feet in height! It seems doubtful whether any contemporary mammalia shared the land with this population of gigantic feathered bipeds.

Mr. Darwin, when describing the recent and fossil mammalia of South America, has dwelt much on the wonderful relationship of the extinct to the living types in that part of the world, inferring from such geographical phenomena that the existing species are all related to the extinct ones which preceded them by a bond of common descent.

Climate of the Post-pliocene Period.—The evidence as to the climate of Europe during this epoch is somewhat conflicting. The fluviatile and land-shells are all of existing species, but their geographical range has not always been the same as at present. Some, for example, which then lived in Britain are now only found in Norway and Finland, probably implying that the Post-pliocene climate of Britain was colder, especially in the winter. So also the reindeer and the musk-ox (Ovibos moschatus), now inhabitants of the Arctic regions, occur fossil in the valleys of the Thames and Avon, and also in France and Germany, accompanied in most places by the mammoth and the woolly rhinoceros. At Grays in Essex, on the other hand, another species both of elephant and rhinoceros occurs, together with a hippopotamus and the Cyrena fluminalis, a shell now extinct in Europe but still an inhabitant of the Nile and some Asiatic rivers. With it occurs the Unio littoralis, now living in the Seine and Loire. In the valley of the Somme flint tools have been found associated with Hippopotamus major and Cyrena fluminalis in the lower-level Post-pliocene gravels; while in the higher-level (and more ancient) gravels similar tools are more abundant, and are associated with the bones of the mammoth and other Post-pliocene quadrupeds indicative of a colder climate.

It is possible that we may here have evidence of summer and winter migrations rather than of a general change of temperature. Instead of imagining that the hippopotamus lived all the year round with the musk-ox and lemming, we may rather suppose that the apparently conflicting evidence may be due to the place of our observations being near the boundary line of a northern and southern fauna, either of which may have advanced or receded during comparatively slight and temporary fluctuations of climate. There may then have been a continuous land communication between England and the North of Siberia, as well as in an opposite direction with Africa, then united to Southern Europe.

In drift at Fisherton, near Salisbury, thirty feet above the river Wiley, the Greenland lemming and a new species of the Arctic genus Spermophilus have been found, along with the mammoth, reindeer, cave-hyæna, and other mammalia suited to a cold climate. A flint implement was taken out from beneath the bones of the mammoth. In a higher and older deposit in the vicinity, flint tools like those of Amiens have been discovered. Nearly all the known Post-pliocene quadrupeds have now been found accompanying flint knives or hatchets in such a way as to imply their coexistence with

man; and we have thus the concurrent testimony of several classes of geological facts to the vast antiquity of the human race. In the first place, the disappearance of a great variety of species of wild animals from every part of a wide continent must have required a vast period for its accomplishment; yet this took place while man existed upon the earth, and was completed before that early period when the Danish shell-mounds were formed or the oldest of the Swiss lake-dwellings constructed. Secondly, the deepening and widening of valleys, indicated by the position of the river gravels at various heights, implies an amount of change of which that which has occurred during the historical period forms a scarcely perceptible part. Thirdly, the change in the course of rivers which once flowed through caves now removed from any line of drainage, and the formation of solid floors of stalagmite, must have required a great lapse of time. Lastly, ages must have been required to change the climate of wide regions to such an extent as completely to alter the geographical distribution of many mammalia as well as land and fresh-water shells. The 3000 or 4000 years of the historical period does not furnish us with any appreciable measure for calculating the number of centuries which would suffice for such a series of changes, which are by no means of a local character, but have operated over a considerable part of Europe.

Relative Longevity of Species in the Mammalia and Testacea.—I called attention in 1830* to the fact, which had not at that time attracted notice, that the association in the Post-pliocene deposits of shells, exclusively of living species, with many extinct quadrupeds betokened a longevity of species in the testacea far exceeding that in the mammalia. Subsequent researches seem to show that this greater duration of the same specific forms in the class mollusca is dependent on a still more general law, namely, that the lower the grade of animals, or the greater the simplicity of their structure, the more persistent are they in general in their specific characters throughout vast periods of time. Not only have the invertebrata, as shown by geological data, altered at a less rapid rate than the vertebrata, but if we take one of the classes of the former, as for example the mollusca, we find those of more simple structure to have varied at a slower rate than those of a higher and more complex organisation; the Brachiopoda, for example, more slowly than the lamellibranchiate bivalves, while the latter have been more persistent than the univalves, whether gasteropoda or cephalopoda. In like manner the specific identity of the characters of the foraminifera,

* Principles of Geology, 1st ed., vol. iii, p. 140.

which are among the lowest types of the invertebrata, has outlasted that of the mollusca in an equally decided manner.

Teeth of Post-pliocene Mammalia.—To those who have never studied comparative anatomy, it may seem scarcely credible that a single bone taken from any part of the skeleton may enable a skilful osteologist to distinguish, in many cases, the genus, and sometimes the species, of quadrupeds to which it belonged. Although few geologists can aspire to such knowledge, which must be the result of long practice and study, they will nevertheless derive great advantage from learning, what is comparatively an easy task, to distinguish the principal divisions of the mammalia by the forms and characters of their teeth.

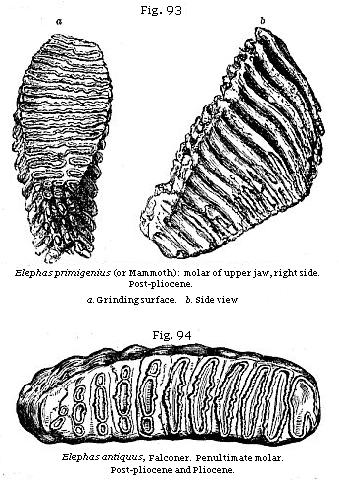

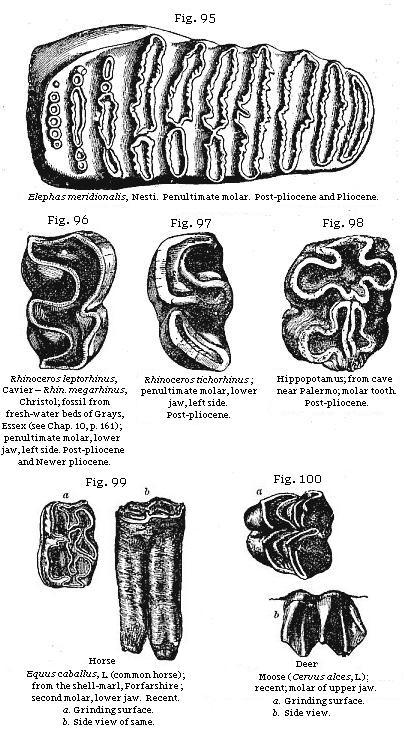

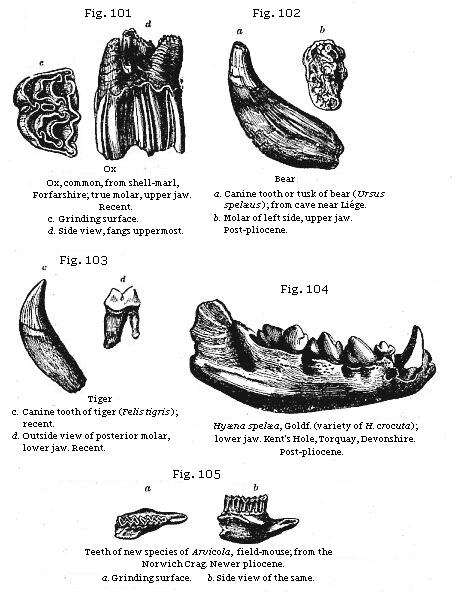

Figures 93 through 105 represent the teeth of some of the more common species and genera found in alluvial and cavern deposits.

On comparing the grinding surfaces of the corresponding molars of the three species of elephants, Figs. 93, 94, 95 it will be seen that the folds of enamel are most numerous in the mammoth, fewer and wider, or more open, in E. antiquus; and most open and fewest in E. meridionalis. It will be also seen that the enamel in the molar of the Rhinoceros tichorhinus (Fig. 97), is much thicker than in that of the Rhinoceros leptorhinus (Fig. 96).