The Student’s Elements of Geology

How we obtain an Insight at the Surface, of the Arrangement of Rocks at great Depths. — Why the Height of the successive Strata in a given Region is so disproportionate to their Thickness. — Computation of the average annual Amount of subaërial Denudation. — Antagonism of Volcanic Force to the Levelling Power of running Water. — How far the Transfer of Sediment from the Land to a neighbouring Sea-bottom may affect Subterranean Movements. — Permanence of Continental and Oceanic Areas.

How we obtain an Insight at the Surface, of the Arrangement of Rocks at Great Depths.— The reader has been already informed that, in the structure of the earth’s crust, we often find proofs of the direct superposition of marine to fresh-water strata, and also evidence of the alternation of deep-sea and shallow-water formations. In order to explain how such a series of rocks could be made to form our present continents and islands, we have not only to assume that there have been alternate upward and downward movements of great vertical extent, but that the upheaval in the areas which we at present inhabit has, in later geological times, sufficiently predominated over subsidence to cause these portions of the earth’s crust to be land instead of sea. The sinking down of a delta beneath the sea-level may cause strata of fluviatile or even terrestrial origin, such as peat with trees proper to marshes, to be covered by deposits of deep-sea origin. There is also no end to the thickness of mud and sand which may accumulate in shallow water, provided that fresh sediment is brought down from the wasting land at a rate corresponding to that of the sinking of the bed of the sea. The latter, again, may sometimes sink so fast that the earthy matter, being intercepted in some new landward depression, may never reach its former resting-place, where, the water becoming clear may favour the growth of shells and corals, and calcareous rocks of organic origin may thus be superimposed on mechanical deposits.

The succession of strata here alluded to would be consistent with the occurrence of gradual downward and upward movements of the land and bed of the sea without any disturbance of the horizontality of the several formations. But

the arrangement of rocks composing the earth’s crust differs materially from that which would result from a mere series of vertical movements. Had the volcanic forces been confined to such movements, and had the stratified rocks been first formed beneath the sea and then raised above it, without any lateral compression, the geologist would never have obtained an insight into the monuments of various ages, some of extremely remote antiquity.

What we have said in Chapter V of dip and strike, of the folding and inversion of strata, of anticlinal and synclinal flexures, and in Chapter VI of denudation at different periods, whether subaërial or submarine, must be understood before the student can comprehend what may at first seem to him an anomaly, but which it is his business particularly to understand. I allude to the small height above the level of the sea attained by strata often many miles in thickness, and about the chronological succession of which, in one and the same region, there is no doubt whatever. Had stratified rocks in general remained horizontal, the waves of the sea would have been enabled during oscillations of level to plane off entirely the uppermost beds as they rose or sank during the emergence or submergence of the land. But the occurrence of a series of formations of widely different ages, all remaining horizontal and in conformable stratification, is exceptional, and for this reason the total annihilation of the uppermost strata has rarely taken place. We owe, indeed, to the side way movements of lateral compression those anticlinal and synclinal curves of the beds already described (Fig. 55), which, together with denudation, subaërial and submarine, enable us to investigate the structure of the earth’s crust many miles below those points which the miner can reach. I have already shown in Fig. 56, how, at St. Abb’s Head, a series of strata of indefinite thickness may become vertical, and then denuded, so that the edges of the beds alone shall be exposed to view, the altitude of the upheaved ridges being reduced to a moderate height above the sea-level; and it may be observed that although the incumbent strata of Old Red Sandstone are in that place nearly horizontal, yet these same newer beds will in other places be found so folded as to present vertical strata, the edges of which are abruptly cut off, as in 2, 3, 4 on the right-hand side of the diagram, Fig. 55.

Why the Height of the Successive Strata in a given Region is so Disproportionate to their Thickness.—We can not too distinctly bear in mind how dependent we are on the joint action of the volcanic and aqueous forces, the one in

disturbing the original position of rocks, and the other in destroying large portions of them, for our power of consulting the different pages and volumes of those stony records of which the crust of the globe is composed. Why, it may be asked, if the ancient bed of the sea has been in many regions uplifted to the height of two or three miles, and sometimes twice that altitude, and if it can be proved that some single formations are of themselves two or three miles thick, do we so often find several important groups resting one upon the other, yet attaining only the height of a few hundred feet above the level of the sea?

The American geologists, after carefully studying the Allegheny or Appalachian mountains, have ascertained that the older fossiliferous rocks of that chain (from the Silurian to the Carboniferous inclusive) are not less than 42,000 feet thick, and if they were now superimposed on each other in the order in which they were thrown down, they ought to equal in height the Himalayas with the Alps piled upon them. Yet they rarely reach an altitude of 5000 feet, and their loftiest peaks are no more than 7000 feet high. The Carboniferous strata forming the highest member of the series, and containing beds of coal, can be shown to be of shallow-water origin, or even sometimes to have originated in swamps in the open air. But what is more surprising, the lowest part of this great Palæozoic series, instead of having been thrown down at the bottom of an abyss more than 40,000 feet deep, consists of sediment (the Potsdam sandstone), evidently spread out on the bottom of a shallow sea, on which ripple-marked sands were occasionally formed. This vast thickness of 40,000 feet is not obtained by adding together the maximum density attained by each formation in distant parts of the chain, but by measuring the successive groups as they are exposed in a very limited area, and where the denuded edges of the vertical strata forming the parallel folds alluded to at page 87 “crop out” at the surface. Our attention has been called by Mr. James Hall, Palæontologist of New York, to the fact that these Palæozoic rocks of the Appalachian chain, which are of such enormous density, where they are almost entirely of mechanical origin, thin out gradually as they are traced to the westward, where evidently the contemporaneous seas allowed organic rocks to be formed by corals, echinoderms, and encrinites in clearer water, and where, although the same successive periods are represented, the total mass of strata from the Silurian to the Carboniferous, instead of being 40,000 is only 4000 feet thick.

A like phenomenon is exhibited in every mountainous country, as, for example, in the European Alps; but we need not go farther than the north of England for its illustration. Thus in Lancashire and central England the thickness of the Carboniferous formation, including the Millstone Grit and Yoredale beds, is computed to be more than 18,000 feet; to this we may add the Mountain Limestone, at least 2000 feet in thickness, and the overlying Permian and Triassic formations, 3000 or 4000 feet thick. How then does it happen that the loftiest hills of Yorkshire and Lancashire, instead of being 24,000 feet high, never rise above 3000 feet? For here, as before pointed out in the Alleghenies, all the great thicknesses are sometimes found in close approximation and in a region only a few miles in diameter. It is true that these same sets of strata do not preserve their full force when followed for indefinite distances. Thus the 18,000 feet of Carboniferous grits and shales in Lancashire, before alluded to, gradually thin out, as Mr. Hull has shown, as they extend southward, by attenuation or original deficiency of sediment, and not in consequence of subsequent denudation, so that when we have followed them for about 100 miles into Leicestershire, they have dwindled away to a thickness of only 3000 feet. In the same region the Carboniferous limestone attains so unusual a thickness—namely, more than 4000 feet—as to appear to compensate in some measure for the deficiency of contemporaneous sedimentary rock.*

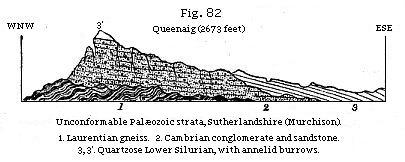

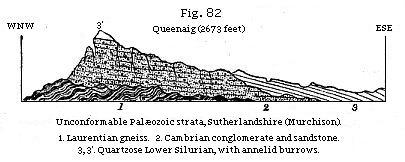

It is admitted that when two formations are unconformable their fossil remains almost always differ considerably. The break in the continuity of the organic forms seems connected with a great lapse of time, and the same interval has allowed extensive disturbance of the strata, and removal of parts of them by denudation, to take place. The more we extend our investigations the more numerous do the proofs of these breaks become, and they extend to the most ancient rocks yet discovered. The oldest examples yet brought to light in the British Isles are on the borders of Rosshire and Sutherlandshire, and have been well described by Sir Roderick Murchison, by whom their chronological relations were admirably worked out, and proved to be very different from those which previous observers had imagined them to be. I had an opportunity in the autumn of 1869 of verifying the splendid section given in Fig. 82 by climbing in a few hours from the banks of Loch Assynt to the summit of the mountain called Queenaig, 2673 feet high.

The formations 1, 2, 3, the Laurentian, Cambrian, and

* Hull, Quart. Geol. Journ., vol. xxiv, p. 322, 1868.

Silurian, to be explained in Chapters XXV and XXVI, not only occur in succession in this one mountain, but their unconformable junctions are distinctly exposed to view.

To begin with the oldest set of rocks, No. 1; they consist chiefly of hornblendic gneiss, and in the neighbouring Hebrides form whole islands, attaining a thickness of thousands of feet, although they have suffered such contortions and denudation that they seldom rise more than a few hundred feet above the sea-level. In discordant stratification upon the edges of this gneiss reposes No. 2, a group of conglomerate and purple sandstone referable to the Cambrian (or Longmynd) formation, which can elsewhere be shown to be characterised by its peculiar organic remains. On this again rests No. 3, a lower member of the important group called Silurian, an outlier of which, 3', caps the summit of Queenaig, attesting the removal by denudation of rocks of the same age, which once extended from the great mass 3 to 3'. Although this rock now consists of solid quartz, it is clear that in its original state it was formed of fine sand, perforated by numerous lob-worms or annelids, which left their burrows in the shape of tubular hollows Fig. 563 of Arenicolites), hundreds, nay thousands, of which I saw as I ascended the mountain.

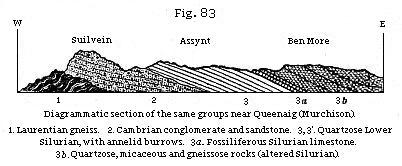

In Queenaig we only behold this single quartzose member of the Silurian series, but in the neighbouring country (see Fig. 83) it is seen to the eastward to be followed by

limestones, 3a, and schists, 3b, presenting numerous folds, and becoming more and more metamorphic and crystalline, until at length, although very different in age and strike, they much resemble in appearance the group No. 1. It is very seldom that in the same country one continuous formation, such as the Silurian, is, as in this case, more fossiliferous and less altered by volcanic heat in its older than in its newer strata, and still more rare to find an underlying and unconformable group like the Cambrian retaining its original condition of a conglomerate and sandstone more perfectly than the overlying formation. Here also we may remark in regard to the origin of these Cambrian rocks that they were evidently produced at the expense of the underlying Laurentian, for the rounded pebbles occurring in them are identical in composition and texture with that crystalline gneiss which constitutes the contorted beds of the inferior formation No. 1. When the reader has studied the chapter on metamorphism, and has become aware how much modification by heat, pressure, and chemical action is required before the conversion of sedimentary into crystalline strata can be brought about, he will appreciate the insight which we thus gain into the date of the changes which had already been effected in the Laurentian rocks long before the Cambrian pebbles of quartz and gneiss were derived from them. The Laurentian is estimated by Sir William Logan to amount in Canada to 30,000 feet in thickness. As to the Cambrian, it is supposed by Sir Roderick Murchison that the fragment left in Sutherlandshire is about 3500 feet thick, and in Wales and the borders of Shropshire this formation may equal 10,000 feet, while the Silurian strata No. 3, difficult as it may be to measure them in their various foldings to the eastward, where they have been invaded by intrusive masses of granite, are supposed many times to surpass the Cambrian in volume and density.

But although we are dealing here with stratified rocks, each of which would be several miles in thickness, if they were fully represented, the whole of them do not attain the elevation of a single mile above the level of the sea.

Computation of the Average Annual Amount of Subaërial Denudation.—The geology of the district above alluded to may assist our imagination in conceiving the extent to which groups of ancient rocks, each of which may in their turn have formed continents and oceanic basins, have been disturbed, folded, and denuded even in the course of a few out of many of those geological periods to which our imperfect records relate. It is not easy for us to overestimate

the effects which causes in every day action must produce when the multiplying power of time is taken into account.

Attempts were made by Manfredi in 1736, and afterwards by Playfair in 1802, to calculate the time which it would require to enable the rivers to deliver over the whole of the land into the basin of the ocean. The data were at first too imperfect and vague to allow them even to approximate to safe conclusions. But in our own time similar investigations have been renewed with more prospect of success, the amount brought down by many large rivers to the sea having been more accurately ascertained. Mr. Alfred Tylor, in 1850, inferred that the quantity of detritus now being distributed over the sea-bottom would, at the end of 10,000 years, cause an elevation of the sea-level to the extent of at least three inches.* Subsequently Mr. Croll, in 1867, and again, with more exactness, in 1868, deduced from the latest measurement of the sediment transported by European and American rivers the rate of subaërial denudation to which the surface of large continents is exposed, taking especially the hydrographical basin of the Mississippi as affording the best available measure of the average waste of the land. The conclusion arrived at in his able memoir,† was that the whole terrestrial surface is denuded at the rate of one foot in 6000 years and this opinion was simultaneously enforced by his fellow-labourer, Mr. Geikie, who, being jointly engaged in the same line of inquiry, published a luminous essay on the subject in 1868.

The student, by referring to my “Principles of Geology,”‡ may see that Messrs. Humphrey and Abbot, during their survey of the Mississippi, attempted to make accurate measurements of the proportion of sediment carried down annually to the sea by that river, including not only the mud held in suspension, but also the sand and gravel forced along the bottom.

It is evident that when we know the dimensions of the area which is drained, and the annual quantity of earthy matter taken from it and borne into the sea, we can affirm how much on an average has been removed from the general surface in one year, and there seems no danger of our overrating the mean rate of waste by selecting the Mississippi as our example, for that river drains a country equal to more than half the continent of Europe, extends through twenty degrees of latitude, and therefore through regions enjoying a great variety of climate, and some of its tributaries

* Tylor, Phil. Mag., 4th series, p. 268, 1850.

† Croll, Phil. Mag., 1868, p. 381.

‡ Vol. i, p. 442, 1867.

descend from mountains of great height. The Mississippi is also more likely to afford us a fair test of ordinary denudation, because, unlike the St. Lawrence and its tributaries, there are no great lakes in which the fluviatile sediment is thrown down and arrested in its way to the sea. In striking a general average we have to remember that there are large deserts in which there is scarcely any rainfall, and tracts which are as rainless as parts of Peru, and these must not be neglected as counterbalancing others, in the tropics, where the quantity of rain is in excess. If then, argues Mr. Geikie, we assume that the Mississippi is lowering the surface of the great basin which it drains at the rate of one foot in 6000 years, 10 feet in 60,000 years, 100 feet in 600,000 years, and 1000 feet in 6,000,000 years, it would not require more than about 4,500,000 years to wear away the whole of the North American continent if its mean height is correctly estimated by Humboldt at 748 feet. And if the mean height of all the land now above the sea throughout the globe is 1000 feet, as some geographers believe, it would only require six million years to subject a mass of rock equal in volume to the whole of the land to the action of subaërial denudation. It may be objected that the annual waste is partial, and not equally derived from the general surface of the country, inasmuch as plains, water-sheds, and level ground at all heights remain comparatively unaltered; but this, as Mr. Geikie has well pointed out, does not affect our estimate of the sum total of denudation. The amount remains the same, and if we allow too little for the loss from the surface of table-lands we only increase the proportion of the loss sustained by the sides and bottoms of the valleys, and vice versa.*

Antagonism of Volcanic Force to the Levelling Power of Running Water.—In all these estimates it is assumed that the entire quantity of land above the sea-level remains on an average undiminished in spite of annual waste. Were it otherwise the subaërial denudation would be continually lessened by the diminution of the height and dimensions of the land exposed to waste. Unfortunately we have as yet no accurate data enabling us to measure the action of that force by which the inequalities of the surface of the earth’s crust may be restored, and the height of the continents and depth of the seas made to continue unimpaired. I stated in 1830 in the “Principles of Geology,”† that running water and volcanic action are two antagonistic forces; the one labouring

* Trans. Geol. Soc. Glasgow, vol. iii, p. 169.

† 1st ed., chap. x, p. 167, 1830; see also 10th ed., vol. i, chap. xv, p. 327, 1867.

continually to reduce the whole of the land to the level of the sea, the other to restore and maintain the inequalities of the crust on which the very existence of islands and continents depends. I stated, however, that when we endeavour to form some idea of the relation of these destroying and renovating forces, we must always bear in mind that it is not simply by upheaval that subterranean movements can counteract the levelling force of running water. For whereas the transportation of sediment from the land to the ocean would raise the general sea-level, the subsidence of the sea-bottom, by increasing its capacity, would check this rise and prevent the submergence of the land. I have, indeed, endeavoured to show that unless we assume that there is, on the whole, more subsidence than upheaval, we must suppose the diameter of the planet to be always increasing, by that quantity of volcanic matter which is annually poured out in the shape of lava or ashes, whether on the land or in the bed of the sea, and which is derived from the interior of the earth. The abstraction of this matter causes, no doubt, subterranean vacuities and a corresponding giving way of the surface; if it were not so, the average density of parts of the interior would be always lessening and the size of the planet increasing.*

Our inability to estimate the amount or direction of the movements due to volcanic power by no means renders its efficacy as a land-preserving force in past times a mere matter of conjecture. The student will see in Chapter XXIV that we have proofs of Carboniferous forests hundreds of miles in extent which grew on the lowlands or deltas near the sea, and which subsided and gave place to other forests, until in some regions fluviatile and shallow-water strata with occasional seams of coal were piled one over the other, till they attained a thickness of many thousand feet. Such accumulations, observed in Great Britain and America on opposite sides of the Atlantic, imply the long-continued existence of land vegetation, and of rivers draining a former continent placed where there is now deep sea.

It will be also seen in Chapter XXV that we have evidence of a rich terrestrial flora, the Devonian, even more ancient than the Carboniferous; while on the other hand, the later Triassic, Oolitic, Cretaceous, and successive Tertiary periods have all supplied us with fossil plants, insects, or terrestrial mammalia; showing that, in spite of great oscillations of level and continued changes in the position of land and sea, the volcanic forces have maintained a due propor-

* Principles, vol. ii, p. 237; also 1st ed., p. 447, 1830.

tion of dry land. We may appeal also to fresh-water formations, such as the Purbeck and Wealden, to prove that in the Oolitic and Neocomian eras there were rivers draining ancient lands in Europe in times when we know that other spaces, now above water, were submerged.

How far the Transfer of Sediment from the Land to a Neighbouring Sea-bottom may affect Subterranean Movements.—Little as we understand at present the laws which govern the distribution of volcanic heat in the interior and crust of the globe, by which mountain chains, high table-lands, and the abysses of the ocean are formed, it seems clear that this heat is the prime mover on which all the grander features in the external configuration of the planet depend.

It has been suggested that the stripping off by denudation of dense masses from one part of a continent and the delivery of the same into the bed of the ocean must have a decided effect in causing changes of temperature in the earth’s crust below, or, in other words, in causing the subterranean isothermals to shift their position. If this be so, one part of the crust may be made to rise, and another to sink, by the expansion and contraction of the rocks, of which the temperature is altered.

I can not, at present, discuss this subject, of which I have treated more fully elsewhere,* but may state here that I believe this transfer of sediment to play a very subordinate part in modifying those movements on which the configuration of the earth’s crust depends. In order that strata of shallow-water origin should be able to attain a thickness of several thousand feet, and so come to exert a considerable downward pressure, there must have been first some independent and antecedent causes at work which have given rise to the incipient shallow receptacle in which the sediment began to accumulate. The same causes there continuing to depress the sea-bottom, room would be made for fresh accessions of sediment, and it would only be by a long repetition of the depositing process that the new matter could acquire weight enough to affect the temperature of the rocks far below, so as to increase or diminish their volume.

Permanence of Continental and Oceanic Areas.—If the thickness of more than 40,000 feet of sedimentary strata before alluded to in the Appalachians proves a preponderance of downward movements in Palæozoic times in a district now forming the eastern border of North America, it also proves, as before hinted, the continued existence and waste of some neighbouring continent, probably formed of Laurentian

* Principles, vol. ii, p. 229, 1868.

rocks, and situated where the Atlantic now prevails. Such an hypothesis would be in perfect harmony with the conclusions forced upon us by the study of the present configuration of our continents, and the relation of their height to the depth of the oceanic basins; also to the considerable elevation and extent sometimes reached by drift containing shells of recent species, and still more by the fact of sedimentary strata, several thousand feet thick, as those of central Sicily, or such as flank the Alps and Apennines, containing fossil Mollusca sometimes almost wholly identical with species still living.

I have remarked elsewhere* that upward and downward movements of 1000 feet or more would turn much land into sea and sea into land in the continental areas and their borders, whereas oscillations of equal magnitude would have no corresponding effect in the bed of the ocean generally, believed as it is to have a mean depth of 15,000 feet, and which, whether this estimate be correct or not, is certainly of great profundity. Subaërial denudation would not of itself lessen the area of the land, but would tend to fill up with sediment seas of moderate depth adjoining the coast. The coarser matter falls to the bottom near the shore in the first still water which it reaches, and whenever the sea-bottom on which this matter has been thrown is slightly elevated, it becomes land, and an upheaval of a thousand feet causes it to attain the mean elevation of continents in general.

Suppose, therefore, we had ascertained that the triturating power of subaërial denudation might in a given time—in three, or six, or a greater number of millions of years—pulverise a volume of rock equal in dimensions to all the present land, we might yet find, could we revisit the earth at the end of such a period, that the continents occupied very much the same position which they held before; we should find the rivers employed in carrying down to the sea the very same mud, sand, and pebbles with which they had been charged in our own time, the superficial alluvial matter as well as a great thickness of sedimentary strata would inclose shells, all or a great part of which we should recognise as specifically identical with those already known to us as living. Every geologist is aware that great as have been the geographical changes in the northern hemisphere since the commencement of the Glacial Period, there having been submergence and re-emergence of land to the extent of 1000 feet vertically, and in the temperate latitudes great vicissitudes of climate, the marine mollusca have not changed, and the

* Principles, vol. i, p. 265, 1867.

same drift which had been carried down to the sea at the beginning of the period is now undergoing a second transportation in the same direction.

As when we have measured a fraction of time in an hour-glass we have only to reverse the position of our chronometer and we make the same sand measure over again the duration of a second equal period, so when the volcanic force has remoulded the form of a continent and the adjoining sea-bottom, the same materials are made to do duty a second time. It is true that at each oscillation of level the solid rocks composing the original continent suffer some fresh denudation, and do not remain unimpaired like the wooden and glass framework of the hour-glass, still the wear and tear suffered by the larger area exposed to subaërial denudation consists either of loose drift or of sedimentary strata, which were thrown down in seas near the land, and subsequently upraised, the same continents and oceanic basins remaining in existence all the while.

From all that we know of the extreme slowness of the upward and downward movements which bring about even slight geographical changes, we may infer that it would require a long succession of geological periods to cause the submarine and supramarine areas to change places, even if the ascending movements in the one region and the descending in the other were continuously in one direction. But we have only to appeal to the structure of the Alps, where there are so many shallow and deep water formations of various ages crowded into a limited area, to convince ourselves that mountain chains are the result of great oscillations of level. High land is not produced simply by uniform upheaval, but by a predominance of elevatory over subsiding movements. Where the ocean is extremely deep it is because the sinking of the bottom has been in excess, in spite of interruptions by upheaval.

Yet persistent as may be the leading features of land and sea on the globe, they are not immutable. Some of the finest mud is doubtless carried to indefinite distances from the coast by marine currents, and we are taught by deep-sea dredgings that in clear water at depths equalling the height of the Alps organic beings may flourish, and their spoils slowly accumulate on the bottom. We also occasionally obtain evidence that submarine volcanoes are pouring out ashes and streams of lava in mid-ocean as well as on land (see Principles, vol. ii, p. 64), and that wherever mountains like Etna, Vesuvius, and the Canary Islands are now the site of eruptions, there are signs of accompanying upheaval, by

which beds of ashes full of recent marine shells have been uplifted many hundred feet. We need not be surprised, therefore, if we learn from geology that the continents and oceans were not always placed where they now are, although the imagination may well be overpowered when it endeavours to contemplate the quantity of time required for such revolutions.

We shall have gained a great step if we can approximate to the number of millions of years in which the average aqueous denudation going on upon the land would convey seaward a quantity of matter equal to the average volume of our continents, and this might give us a gauge of the minimum of volcanic force necessary to counteract such levelling power of running water; but to discover a relation between these great agencies and the rate at which species of organic beings vary, is at present wholly beyond the reach of our computation, though perhaps it may not prove eventually to transcend the powers of man.