|

John Day Fossil Beds Historic Resources Study |

|

Chapter Four:

SETTLEMENT (continued)

Hostilities Erupt

The sudden rush of gold seekers to central and eastern Oregon exacerbated tensions and heightened the prospects for conflict with native inhabitants. This reality was driven by several factors, chief of which was the slow implementation of treaty policy in the region.

In July, 1862, J. M. Kirkpatrick secured appointment as Special Indian Agent to assess the situation in the country occupied by the Northern Paiutes. Unable to find an interpreter at either Warm Springs or the Umatilla reservations, Kirkpatrick nevertheless set out east over the Oregon Trail to the mines on the Powder River. Along the way, Kirkpatrick found ample evidence of gold rush. "For a distance of over one hundred and forty miles in length, extending from Burnt River basin southwest to the south fork of John Day's river, and from thirty to forty miles in width, a great many men are at work mining, and are making from five to fifty dollars per day each," he wrote. He further noted that lode deposits at the head of the John Day, Powder, and Burnt rivers held promise for more sustained mineral production (ARCIA 1863: 265-267).

During the Civil War years, the Oregon legislature took the initiative to mount military expeditions into Northern Paiute country. Volunteers and soldiers, newly recruited into the Oregon Infantry and Oregon Cavalry as token forces at western Army posts, took the place of Army regulars who had rushed east to serve in Union campaigns. The Oregon Infantry spent nearly seven months on the assignment.

In the spring and summer of 1864, Captains John M. Drake and George B. Curry and Lt.-Col. Charles Drew swept with troops through southeastern Oregon, northern Nevada, and southwestern Idaho. "These tribes can be gathered upon a reservation, controlled, subsisted for a short time, and afterwards be made to subsist themselves," wrote Indian Superintendent J. W. Perit Huntington, "for one-tenth the cost of supporting military force in pursuit of them" (ARCIA 1864: 85). Drew, an avid Indian-hater and promoter of military action against the Northern Paiutes, had published a litany of alleged wrongs perpetrated by the Indians. He sought confrontation with them (ARCIA 1863: 56-60).

Captain Drake began the campaign with 160 enlisted men and seven officers from Fort Dalles, leading them into the Harney Basin in April of that year. His instructions were to protect the miners and explore the country not lying within the Indian reservations. The Northern Paiute had raided both the mining camps at Canyon City and the Warm Springs Reservation in the fall of 1863. Drake was to seek restoration of stolen property and drive the hostile Indians away from the settlements. Indian scouts from the Warm Springs Reservation joined the party when it passed their homes. The soldiers ascended the Deschutes and passed over the trail via the Crooked River. On May 18, while on the Crooked River, an advance patrol encountered hostile Indians. The Indians killed twenty-three soldiers and one of the Indian scouts; they wounded several other men. The Northern Paiutes slipped away before the main command converged on the battle site (Knuth 1964: 5-35).

As Drake's force moved on toward the Harney Basin, patrols of both regular soldiers and Indian scouts from Warm Springs made salients toward the South Fork of the John Day and into the upper river valley to try to locate members of Northern Paiute Chief Paulina's band. They failed. Paulina's people continued to harass travelers and packers on the trail to the mines at Canyon City (Knuth 1964: 50-63). In the Harney Basin the soldiers could find no Indians, but on July 7 learned of their actions to the north where they stole thirty or forty head of horses at Canyon City, killed one or two residents, and ran off stock on Bridge Creek. "They are, from all accounts," wrote Drake, "concealed in the mountains about the head of the South Fork of John Days River" (Knuth 1964: 71).

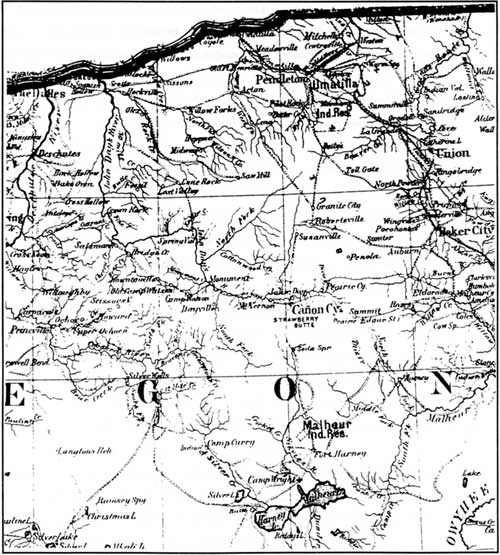

Fig. 10. Drake's 1864 route to "Old Camp

Watson" and "Canyon C[it]y" (Knuth 1964, Map Insert).

The 1864 campaign against the Northern Paiute then shifted north to the mountainous region lying between Harney Basin, the John Day River, and upper Crooked River. Except for a skirmish between the Warm Springs scouts and the hostile Paiutes on July 12, the Oregon Cavalry had little contact or sighting of the Indians. Capt. Drake occupied his days writing his journal and observing the region's geology. On July 16 he noted:

Some soldiers, during the absence of the main body of the troops on the Indian chase, discovered some very fine geological specimens on the crest of a low ridge jutting out from the main chain of the hill opposite our camp. Those specimens consisted of fossil shells imbedded in a hard sand stone. In most cases, the imprint of the shell only is left in the rock; this is very distinct and from appearances I judge the shells to be marine in their character, although I do not feel very confident of it. I went up to the ridge this morning and succeeded in gathering some fine specimens for Mr. [Thomas] Condon at the Dalles, and purpose sending them to him by the next wagon train. It is certainly a great curiosity, and a practical geologist would find a fine field for his profession in delving into the rocky hills of the camp (Knuth 1964: 74-75).

During their patrols in quest of the elusive Indians, the Oregon Cavalry established a number of camps, depots, and temporary forts in central and southeastern Oregon. These posts were established by the Oregon Volunteer Infantry and Oregon Volunteer Cavalry except for Fort Harney, a U.S. Army post. Most were occupied for only a few weeks or a few months (McArthur 1974).

Situated approximately fifteen miles west of the present town of Dayville, Camp Watson was established to protect the well-traveled but vulnerable road from The Dalles to the gold mines at Canyon City, soon to be surveyed as The Dalles-Boise Military Road. In June, 1864, Capt. Richard S. Caldwell, leading Company B of the First Oregon Cavalry and a detachment from Washington Territory, explored the South Fork of the John Day. By July, Caldwell had established Camp Watson at a site on Rock Creek. In the early fall, Caldwell was relieved by Capt. Henry C. Small who relocated Camp Watson to Fort Creek, four miles to the west (Knuth 1964:103-104).

Table 1. Military Establishments in Central Oregon

| Name | Established | Location |

| Camp Maury | May 18, 1864 | T17S, R21E, Sec. 20, W.M., SE side of Maury Creek west of Rimrock Creek, Crook Co. |

| Camp Gibbs | July 21, 1864 | Drake Creek, Crook County |

| Camp Dahlgren | August 22, 1864 | Beaver Creek, Crook County |

| Camp Watson | October 1, 1864 | Five miles west of Antone, Wheeler Co. |

| Camp Logan | Summer, 1865 | Strawberry Creek, six miles south of Prairie City, Grant Co. |

| Camp Currey | August, 1865 | Silver Creek, Harney County |

| Fort Harney | August 16,1867 | Rattlesnake Creek, Harney Co. |

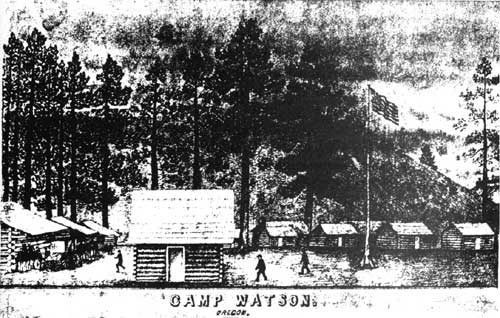

Camp Watson reached fairly respectable physical proportions, arranged around a central quadrangle. Twelve huts for soldiers were aligned on either side of the wagon road at the north end of the quad, with four offers' huts opposite. To the west were a small map house, a hospital, a guard hut and orderly room, and a commissary and quartermaster store. Corrals and stables bordered the east side. All buildings were constructed of logs and roofed with wood shingles. Camp Watson was occupied by the First Oregon Cavalry until May of 1866, and then turned over to the regular army unit its final abandonment in 1869. (Kenny 1957: 4-16).

Tensions in the region did not abate with the military missions. Between September, 1865, and August, 1867, numerous incidents occurred which involved Northern Paiutes and residents of the upper John Day watershed. These ranged from armed encounters and killings to petty thieving, raids of isolated ranches and mining camps, and periodic sweeps by volunteer companies seeking the "enemy." Indian Superintendent Huntington summarized eight packed pages of these encounters in his report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1867 (ARCIA 1867: 95-103). Indians suffered numerous deaths; stock drivers lost their animals and cursed the Indians. Indians raided settlements and escaped. Troops rounded up Indians and killed them. The situation was nearly guerilla warfare.

Fig. 11 Sketch labeled Camp Watson, n.d.

(OHS Collections)

Resolution of conflicts with the Northern Paiute, of a sort, came with the executive order of President Ulysses S. Grant on September 12, 1872, to create the Malheur Reservation. A vast tract sprawling across the meadows of the Harney Basin and encompassing Malheur Lake, Oregon's largest lake, the reservation was designated as a permanent homeland for the Northern Paiute. It was enlarged on May 15, 1875, to 1.7 million acres, but pressures mounted rapidly for its termination. On January 28, 1876, the president virtually abolished the reservation. Cattle drovers such as Peter French and David Shirk had discerned the potentials for wealth if they controlled key water resources and grazing. The press was on to dismember the Malheur Reservation. For the Northern Paiute the decision was a disaster. They would survive, largely landless, until securing individual, public domain allotments in 1897 and in obtaining in 1935 the Burns Paiute Indian Colony, a tract of 760.32 acres near Burns, Oregon. They also retained ten acres at old Fort Harney (Ruby and Brown 1986: 9,158-159).

A last scare of Indian hostilities swept through the John Day Valley in 1878 with the outbreak of the Bannock War. The troubles erupted in Idaho because of trespass by sheepherders onto Indian lands. The Bannock swept into eastern Oregon to rally the discontented Northern Paiute. The efforts to forge common cause against the Euro-Americans largely failed. Following a brisk battle at Silver Creek on June 23, the Bannock turned north toward the Columbia River to escape soldiers of the U.S. Army. They engaged in an abbreviated exchange near Canyon City, killing one man and wounding two others. The Bannocks moved from the South Fork of the John Day to the Long Creek Valley, stealing, burning cabins, and fleeing. The final conflicts occurred at Willow Springs and Birch Creek. The Umatilla Indians did not rally and, in fact, joined in opposing the Bannocks and killed Egan, a Northern Paiute leader who was with the hostile forces. The continued pursuit compelled some Bannocks to try to cross the Columbia. Their war was crushed with many deaths; the Bureau of Indian Affairs removed the survivors to the small reservation at Fort Hall, Idaho (Ruby and Brown 1986: 8-9; Brimlow 1938).

The Bannock War of 1878 contributed to considerable local lore about Indian hostilities in the John Day watershed. Because of settlement, many Euro Americans had personal stories to tell. Families fled isolated homesteads and residences, forted up at defensible positions, and waited for the troubles to subside. The Dedman homestead near Twickenham was one of these locations. Built of hewn logs with heavily shuttered windows, the building had holes in its walls for rifle ports. A. S. MacAllister and Peasley owned the ranch in the 1870s. It subsequently passed to Zachary Keys in 1906. An account by Dickse Williams summarized the fate of most of the "forts" of the era of Indian hostilities: "As far as can be determined, the [Dedman] house was never under attack by Indians . . " (Oregon Society Daughters of the American Revolution 1959: 28-29).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

joda/hrs/hrs4c.htm

Last Updated: 25-Apr-2002