|

John Day Fossil Beds Historic Resources Study |

|

Chapter Six:

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

The economy of the upper John Day basin is grounded in the rich natural resources of the region. Since the early 1860s, minerals, grasslands, meadowlands, and forests have provided the basis of human livelihood. The first wave of economic development to sweep the John Day country was gold mining. Ultimately, gold mining would have far-reaching effects on the landscape, altering the banks of rivers and streams, and ushering in early forms of agriculture and town-building. Cattle ranching and sheep ranching soon surpassed mining as an economic pursuit and a way of life. These occupations held sway through the first three decades of the twentieth century. After 1940, harvesting and processing the vast stands of timber in the private forests and national forests of Grant and Wheeler counties emerged as the mainstay of the local economy. In all of these industries, small operators and large commercial concerns alike had their hands.

Mining

The fevered rush of miners prospecting streams throughout the interior of the Pacific Northwest was initially driven by the gold strikes of 1858 in the Fraser River region in British Columbia. The riches were sufficiently attractive to draw miners from southern Oregon and California (Reinhart 1962: 108-135). In succeeding years, gold seekers repeatedly trespassed on Indian reservations and unceded lands throughout the Columbia Plateau in their search for the precious metal. R. H. Lansdale, Indian Agent at Fort Simcoe on the Yakima Reservation in Washington Territory, noted on August 15, 1860, the great numbers of white men passing through the region. "Many of these men," he wrote, "are miners from California, and I record with great pleasure, that, as far as has come to my knowledge, they have always respected the rights and feelings of the helpless Indians" (ARCIA 1860: 205).

Gold seekers repeatedly attempted to re-find the legendary "Blue Bucket Nuggets," a rich strike allegedly made in 1845 during the transit of overland emigrants following the hapless Stephen H. L. Meek. These travelers attempted to blaze a new emigrant route west from Fort Boise through central Oregon to the Cascades with the intent to enter the upper Willamette Valley. The route proved difficult, indeed deadly for some, and took them through the northern Harney Basin and across the High Desert toward the Deschutes River. Unable to find a pass in the Cascades, they descended the rugged banks of the Deschutes and rejoined the Oregon Trail at The Dalles. Serious attempts to relocate the mine continued for over a century after the initial discovery (Clark and Tiller 1966; Brogan 1977: 40-41).

Several accounts suggests that golden potentials lurked in the Blue and Strawberry mountains. Members of Capt. Wallen's military exploring party brought in reports of gold on the Malheur River. In the spring of 1861, J. L. Adams recounted in Portland that he had found gold in the "upper country." Adams then led an exploring party to the John Day River, found prospects, returned to Portland, and in the early fall of 1861 set out again for the North Fork of the John Day. W. S. Failing and E. Lewis, both members of the initial exploring group, set out in November with thirty-two men and fifty-six animals loaded with supplies for six months of residency. By January, 1862, they had erected cabins at Otter Bar, a site somewhere on the upper John Day River. Hostile encounters with Indians caused the men to flee in February to The Dalles, but they soon returned (Nedry 1952: 238-240).

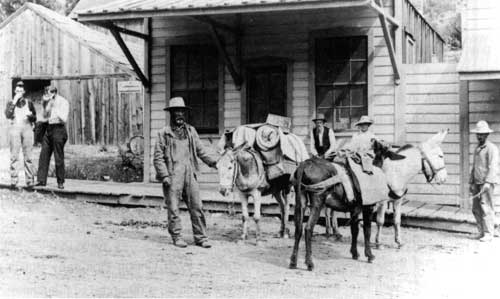

Fig. 39. Miners with pack mules on the

streets of Canyon City, ca. 1920 (OrHi 57533).

In June of 1862, a strike on Canyon Creek drew thousands to the John Day basin. The rush to Canyon City and other mountainous areas in what is now eastern Grant County triggered far-reaching change in the region — permanent settlement, the advent of ranching and agriculture, and the beginnings of large-scale resource extraction. Although the rush was over by 1870, the pursuit of gold remained an important factor in the economy of Grant County well into the twentieth century, often through well-capitalized industrial operations. One source has estimated that, by 1972, as much as $30,000,000 in gold had been mined from the gravel beds of Canyon Creek and the John Day River (Thayer 1972: 4).

In December, 1862, miners drafted the regulations of the John Day Mining District, a region extending up the river to its summit with the Malheur watershed and the ridge west of Canyon Creek. They set creek claims at seventy-five running feet on the stream from one high water mark to the other. Bank claims were fixed at seventy-five running feet on a stream back 300 feet from creek claims. Shaft claims were set at seventy-five feet on the front and extended to the center of the hill. Gulch claims were set at 150 running feet in the gulch and fifty feet to either side of the channel. Each miner was allowed two claims, but each had to be of a different type. Significantly, the racism of the miners surfaced in these initial agreements: "No Asiatic shall be allowed to mine in this district," read the ordinance (Oliver 1961: 21-22). Miners from other diggings who had encountered the hardy Chinese attempted to block their presence.

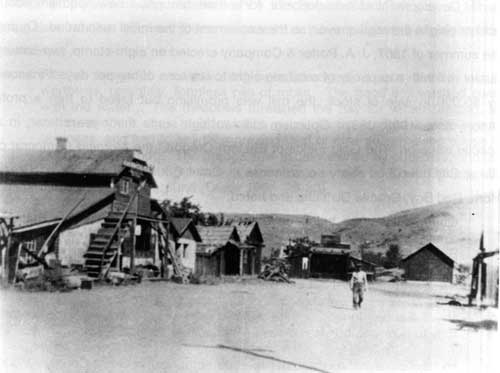

Chinese miners did, nonetheless, enter the area. Dozens lived at remote placer and lode mines. Two large concentrations of Chinese residents occurred at Canyon City and John Day. John Day's 'Chinatown' was a substantial settlement on the banks of Canyon Creek. Although the Chinese population had sharply declined by 1900, two notable figures remained their entire lives and became an integral part of the John Day community — the herbal doctor Ing Hay and his friend and business partner Lung On. The two men operated the Kam Wah Chung & Company store, which served as a doctor's office, trading post, pharmacy, social club, bank, assay office, and a shrine. Doc Hay was a legendary figure in central Oregon, and his herbal remedies were popular with Chinese and Euro-Americans alike. The Kam Wah Chung Company Building (built ca. 1867, with later additions) still survives today, a reminder of the Chinese experience in the gold mines of eastern Oregon (Hartwig 1973).

Fig. 40. Chinatown at John Day, 1909.

Kam Wah Chung & Co. Building to the left (OrHi 53764).

Miners brought considerable energy and new technology to central Oregon. Chief among their projects was construction of ditches and flumes to divert water to the diggings. Early in 1862 the claimants at Prairie Diggings formed a joint stock company to build a ditch for two miles. They completed it by early summer. Miners at Marysville and Canyon City built a ditch to divert large amounts of water from Indian and Big Pine creeks through twelve miles of hand-dug canal. This ditch, constructed in 1862, continued in operation into the early twentieth century. The early miners also felled trees, sawed lumber, constructed flumes, and, as demand dictated, built sawmills to help construct the towns where they settled (Anonymous 1902: 386-387).

Development of lode deposits, for a time, brought a new optimism about gold mining in the region, even as the excitement of the initial rush faded. During the summer of 1867, J. A. Porter & Company erected an eight-stamp, two-battery quartz mill with a capacity of crushing eight to ten tons of ore per day. Financed by $5,000 in sale of stock, the mill was promising but failed to turn a profit (Anonymous 1902: 393). Optimism still ran high some thirty years later, in a special issue on "The Gold Fields of Eastern Oregon," the Morning Democrat of Baker City described many active mines in Grant County in the Canyon, Green Horn, Red Boy, Granite Districts, and noted:

Quartz mines are being developed in the old placer districts that are simply astonishing in their richness. . . . At Quartzburg, near the town of Prairie City, are a number of gold bearing ledges, some of which have been worked by arrastras and stamp mills for several years with good results. . . . One prospect in particular, a mile and a half from town [Canyon City], gives much encouragement to its discover, Mr. Isaac Guker. . . Lately Mr. Guker has found nuggets or flat chunks of gold, varying in value from forty to over one-hundred dollars (Anonymous 1898: 25, 33).

Hydraulic mining was another method employed in Grant County. Water in a ditch at a higher elevation was sent down a hose through a narrowing nozzle. The high pressure stream was directed at a hill side or cut bank, washing tons of ore into a sluice where the gold was separated out. The Humboldt Mining Company, among others, ran a large hydraulic operation near Canyon City, using an eight and one-half mile ditch, and 2,600 feet of hydraulic pipe (Anonymous 1898: 35). Remnants of this ditch may still be discernable on the west side of Canyon Creek, just south of Canyon City.

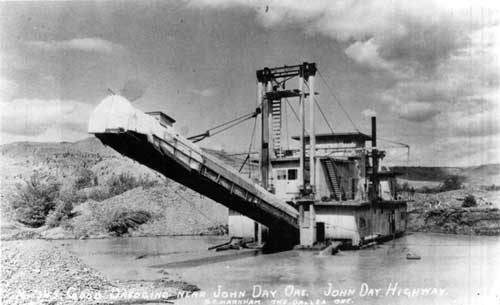

Fig. 41. Gold Dredging near John Day, OR

(OrHi 77491)

Dredging was a third method of mining employed along the John Day River in the early twentieth century A technique particularly destructive to bottomland meadows, dredging tore up former channels of the river, washing away soil, and spitting out acres of telltale mounds of gravel. The dredge would create and float on its own pond, using water diverted from a nearby stream. Dredging operations were established by the Empire Gold Dredging & Mining. Long-time rancher Herman Oliver summed up the impact of dredging on the landscape:

After a beautiful meadow had been dredged, it was turned into a worthless, unsightly, formless pile of rocks. The good soil washed away with the water. . . The meadows furnished the hay for winter feeding, so some ranchers, their meadowlands gone, no longer had a year-around business, and had to sell their grazing land or else go somewhere lese to get more hay land.... The dredge was usually owned by outsiders, and the profits went to San Francisco or someplace outside of Grant County. So the county lost all around (Oliver 1961: 29-30).

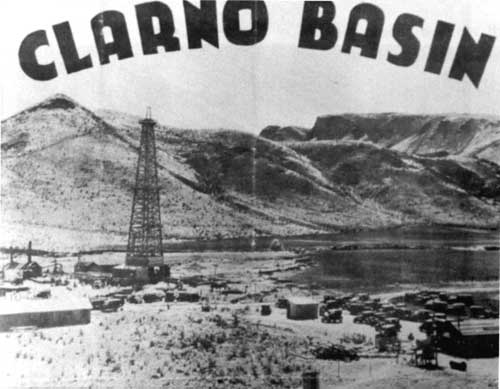

Although Wheeler County lacked the concentration of rich gold deposits of Grant County, the Clarno area witnessed brief excitement over oil. In 1927, the Clarno Basin Oil Company sunk one well on the Hilton Ranch at the mouth of Pine Creek. The company sold shares to hopeful investors at $10 a share, and spent an estimated $300,000, drilling to a depth of 4,800 feet. Promotional literature proclaimed, "One Good speculation is Worth a Lifetime of Saving!" and promised that the Clarno basin was proven to contain oil and gas. Eager visitors from all over the state congregated at the field on Sunday afternoons, in the hopes of seeing oil come gushing forth. In the end, the prospect yielded natural gas but no oil (McNeil 1953: 273; Fussner 1975: 29).

Fig. 42. Detail from promotional

literature for the Clarno Basin Development Company, ca 1927, F K Lentz

1996 (National Park Service).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

joda/hrs/hrs6.htm

Last Updated: 25-Apr-2002