3. Improving Memory

Before we study the various positive influences on memory please indulge in a little experiment. The results will illustrate some important principles.

Test No. Two

Read through the following list once only. Read slowly and concentrate. Then look away and write down as many of the words as you recall in any order.

Grass. Paper. Cat. Knife. Love. Bird. Tree. Desk. Truth. Table. Fork. Pen. Stream. Wisdom. Stream. Flower. Zulu. Radio. Ruler. Blue. Sheep. Meaning. Field. Pencil. Carbon.

When you have written down the list of words that you have recalled, you will normally find certain things to be true. And these facts illustrate several important principles.

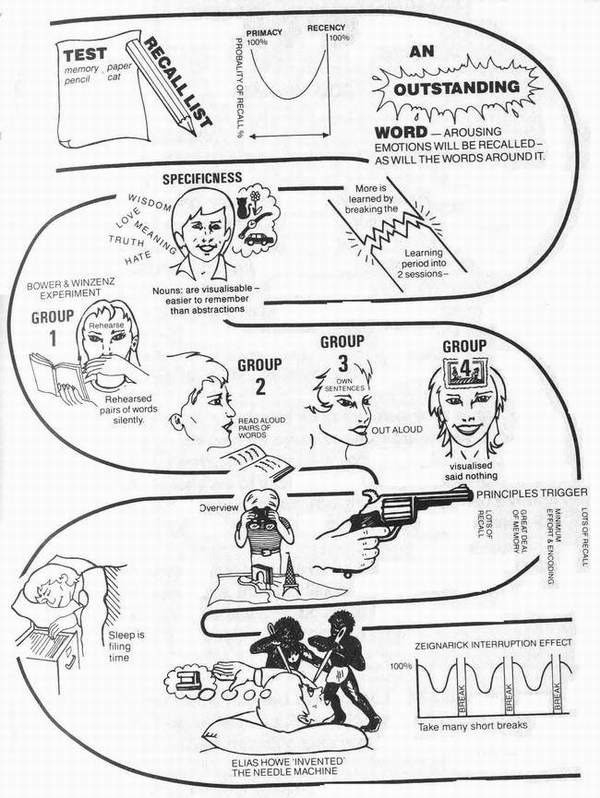

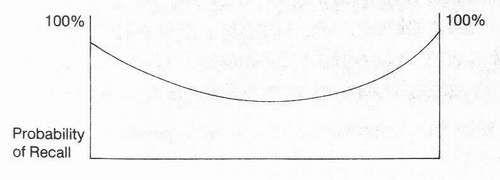

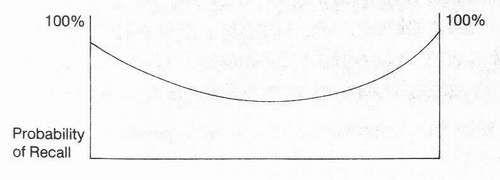

1. Primacy

You tend to remember more from the beginning of a test or a learning session. So you probably remembered `grass' and `paper'. This is called the PRIMACY EFFECT.

2. Recency

You also tend to remember more from the end of a learning session. So you probably remembered `pencil' and `carbon'. This is called the RECENCY EFFECT.

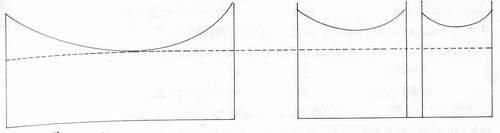

If you put these two effects together and plot your typical learning efficiency in memorising a list or over a period of study, say a lecture or a lesson, the effect is shown in the following figure.

3. The Von Restorff Effect

There was probably another word that you remembered - the word Zulu. The word stood out from the list because it was different (and may have carried a quite strong visual association).

Von Restorff discovered something upon which professional memory men rely heavily. If you want to remember something, ensure it is outstanding in some way - colourful, bizarre, funny, vulgar. A bright red flower on a black dress is memorable, a subtle floral print dress may be pretty, but it is not memorable.

Outstanding elements have been measured to increase our arousal level and our attention - and you will always remember something better if it is presented in a way that either focuses increased attention, or is arousing to one or other of your senses or emotions.

Interestingly, you might also have remembered the words 'flower' and/or `radio' which straddle 'Zulu' on the list - because the increased arousal and attention often improves recall for words or events around the original item.

By the simple expedient of inserting high recall items into a series of words, or into a lesson or lecture, you can provide a boost for attention, and therefore for encoding, retention and recall.

There is an interesting implication to the above. The longer the lesson or lecture, the more time there is for the fall off in attention and recall to take place. The simple device of splitting up a lesson into two parts with a break in between will increase the overall level of recall - because there is more Primacy and Recency Effect at work.

Specificness

If we go back again to the list of words you recalled, most people will notice that they remembered fewer of the words 'love', 'truth', 'wisdom' or 'meaning'. These words are concepts and it is more difficult to give them a concrete reality or image. In contrast, the easiest words to remember are always nouns and adjectives because they can be visualised - and as we shall see visualisation is one of the keys to memory.

For the above reasons, teaching a new language should be similar to learning your own language. Children learn the words for objects first and only later do they learn the words of abstractions like 'precedence' or `prosperity'.

Organisation

Before we leave Test Two, have a look at the list you made. It is more than likely that you wrote the words down in clusters or groups. There were in fact several categories in the list - animals, things from the countryside, items you might find in an office, items from a kitchen and abstract concepts.

Although they were not grouped together in the list it is quite likely that you recalled them in groups.

The world famous researcher Canadian psychologist, Endel Tulving of Toronto University has conducted many experiments on the role of organisation in memory. One of the most dramatic involved two groups of students, each of whom were given 100 cards on which was a printed word. Half were instructed to learn the words by memorising them. The other half was instructed to sort the words out into categories.

When they were later tested the sorters or 'organisers' did equally as well as the 'memorisers' - in other words the active involvement in organising was sufficient to create learning. Tulving concluded that when we fry fo remember something new we instinctively repeat if for ourselves. It is quite probable that it is not the repetition that is so important, as the fact that our minds are constructing associations and patterns between the words and imposing a subjective organisation on the material.

Suppose you want to remember a list of words say, - bee, pan, lamp, proud, trowel. You will more readily remember the words if you make up a sentence or sentences connecting the words in the form of a short story. You would remember it even better if the story was easy to visualise and best of all if you could picture a story that was dramatic, or vulgar, or comic or in some way involved your emotions.

Two more research projects emphasise the importance of active involvement with new material and both studies are relevant to the learning of languages.

W. Kintsch and his associates conducted an experiment in 1971 to teach three groups of subjects three new nouns. One group were instructed to read the words aloud. The second group were instructed to sort the words by type of word. The third group were asked to form one sentence that contained all three words. Retention of the third group was 250% better.

In the second project researchers G. Bower and D. Winzenz took four groups and required them to learn pairs of unrelated nouns.

Group 1 simply rehearsed the pairs silently

Group 2 read aloud a sentence containing the pairs of words.

Group 3 made up their own sentence and spoke them out loud.

Group 4 visualised a mental picture in which the words had a vivid interaction with each other, but said nothing out loud.

Each group performed better than the one before. The more active the involvement the deeper the learning.

The conclusions were fully validated by educational psychologists Glanzer and Meinzer who asked two groups to learn a list of new words. One group was asked to simply repeat the words six times each. The second group used the same time to think about the word and "process it mentally". The second group's recall was markedly superior.

A story is in fact a good mnemonic or memory aid and the more elaborate the story the better. A story links words to be remembered and it causes you to build up scenes that have visual, sound and sensory associations for you. Moreover the plot, however simple, provides an associative thread, so that it is normally enough to recall the theme and the theme then triggers recall of more material. If you can create a powerful visual image between two words, remembering one will trigger recall for the other.

Dual Encoding

The reason that a list of items learned in picture form is more easily learned than an equivalent list of printed words, is that the former are learned visually as well as verbally.

A picture list involves what psychologists call dual encoding - and we know that the stronger the encoding the more durable the memory and the easier the recall. In fact the ideal is not just dual but multiple sense encoding.

Principles

Consider the following sequence of letters

How long do you think it would take to remember the sequence correctly? In fact you can do if in 20 seconds. By discovering the principle involved. Start with the last letter "A" and go up to the top line "C" across to the left "C" down to the bottom line "E" across to the left "L" up to the top "E" etc., i.e.

The sequence spells Accelerated Learning.

Similarly the following sequence 3.6.9.12.15.18.21. does not have to be memorised. You merely need to remember the principle involved. Remembering the principles involved is always more efficient than trying to remember the specifics. Chess masters can play blind-fold chess not because they recall each piece, (they don't), but because they retain the overall patterns involved.

Just how incredibly powerful this can be, is exemplified by the Belgian Master Koltanovski who in 1960 played 56 simultaneous games of blind-fold chess, winning 50 and drawing 6!

When we come to discussing the actual evolution of Accelerated Learning we shall be referring to principles, because they are a way of achieving a great deal of memory with the minimum amount of effort expended on encoding. They `trigger' lots of recall.

In a particularly interesting study, A.S. Reber in 1967 showed that relationships between words are often subconsciously recognised. He took two groups and gave each a list of nonsense words to learn. One group had a list made up of words chosen at random - the other group had a list which was compiled according to a specific rule or principle - but that principle was not specified, it was merely implicit. The second group learned twice as well. The clear conclusion was that rules (and they include grammar) can be learnt from inference and example.

In another very simple example, taken from our own Accelerated Learning German course, we found that English learners found it difficult to remember which words were masculine or feminine or neuter. So we taught them some simple principles (or mnemonics). For example the jingle:- "height of the kite is always female", taught them in 10 seconds that all German words ending in -heit- or -keit- were feminine gender.

When we understand the principle involved - when we say "Aha, I see now" we have given the subject meaning and a personal relevance. We have filed it in our own particular memory - library reference file. We remember very poorly anything that is not meaningful to us, but we remember easily anything that has significance, and particularly emotional significance (Brierly 1966).

Meaning

In 1975 Craik and Tulving reported on an experiment in which subjects were asked to remember words on one of three bases.

The visual appearance of the words - (15%) The sound of the word - (29%) The meaning of the word - (71%)

The figures in brackets are the percentage of correctly recalled words after two presentations of the list. You will see that encoding the basis of meaning is 3-4 times stronger.

To oversimplify. You cannot become involved in something unless you understand it and it has meaning for you personally. Once it has meaning, it is capable of being associated in your mind with other words or facts you already know and understand.

If you are not `involved' with new information it will not be processed at anything but a superficial level. It will "go in one ear and out of the other".

This is why you always remember the results of a problem that was initially difficult to solve.

Involvement then leads to a deeper processing of the material and thence to stronger memory. We have the beginning of a virtuous circle.

Context

You have probably all read the following (shortened) description). "The first group is in. The second group go out and they try to get the first group out. Then when the first group are all out, the second group is in. The first group now goes out and tries to get the second group out. Only when both groups have been in and out twice is there a conclusion. "

An arcane passage, which would defy alI understanding, unless you knew that the description was of a Cricket Match, where a team was "in" until all its batsmen had been bowled "out". So knowing the context in advance made it much easier to understand - and therefore remember.

In memorising anything it is vital to get an overview so that you understand the broad principles involved before you begin.

There is a common place parallel in everyone's life. When you visit a new country or city you look for the landmarks first and then you relate other less important places to them. You need to establish the broad geography (overview) and then systematically fill in the minor areas (detail).

This is a spontaneous and natural mapping principle, which will become significant later in this book. Educational pioneer Charles Schmid likens the importance of context to doing a jigsaw - its ten times harder if you cannot see the picture on the box.

Primitive man evolved memory largely as a way of providing himself with mental maps to record routes and the location of shelter and food. Because he had limited speech, this mapping instinct had to rely largely on an ability to visualise - bring the scene to his mind's eye. Even today primitive tribes in Africa have been shown to possess a much higher degree of visual or eidetic memory - than their Western counterparts. Eidetic memory is that ability which allows the subject to replay scenes in his or her head, - almost like a video replay.

As we shall see the principle of over viewing and mapping out a subject not only provides context and, therefore, meaning but leads to the utilisation of the single most powerful element in memory - visual memory.

Physical Context

The physical environment in which you learn can also have a profound influence on your ability to recall.

The 17th Century British Philosopher - John Locke - quoted an especially odd case of a young man who had learnt to dance.

"and that to great perfection. There happened to stand an old trunk in the room where he had learned. His idea of this remarkable piece of household stuff had so mixed itself with the steps of all his dances, that though in that chamber he could dance excellently well, it was only while that trunk was there, nor could he perform well in any other place, unless that or some other such trunk had its due position in the room."

In an equally bizarre, but persuasive study, Cambridge Psychologist Dr. Alan Baddeley and Dr. Duncan Godden took a group of divers and taught them each 40 unrelated words. Half were taught under water, half were taught ashore. The words that were both learnt underwater and tested underwater were recalled almost twice as well as the words learned ashore, but tested underwater.

The implications of the fact that you recall better in the same environment, are that on-the-job training should be preferable to simulated training, and that most people learn better by learning in the same chair/desk and setting. Conversely, recalling learned material can often bring back the surroundings in which the original learning took place.

R.N. Shiffrin writing in "Models of Human Memory" proved the effectiveness of flash cards in teaching words - and found that his subjects remembered not only the word and its translation, but the size and colour of the letters and often the surroundings they were originally taught in.

Memory and Sleep

One of the major puzzles of psychology is sleep. A recent book entitled 'Landscapes of the Night', written by Chris Evans and Peter Evans, possibly represents "the state of the art" in terms of the function of sleep and dreaming.

Starting from the observation that it is, in evolutionary terms, quite amazing that mammals will risk spending a third of their lives in the highly vulnerable state of unconsciousness known as sleep, the book constructs a most realistic theory of sleep and dreaming.

Chris Evans draws an apt parallel between a human brain and a modern computer. In order for the computer to be reprogrammed it must go "off line" for sometime. This is the period when new programmes are being tested and old ones modified.

In the same way the human brain needs to go "off line". The experiences of the day are reviewed during sleep and assimilated into new patterns of thought, belief, and future behaviour. This is done during the pan`. of sleep when dreams occur. Due to investigative research by Eugene Aserinsky, working with the sleep researcher Nat Kleitman, we now know that dreams occur during paradoxical sleep (so called because the brain is in fact very active), or that portion when there is Rapid Eye Movement (or REM) sleep.

There is much circumstantial evidence that REM sleep may act as a period when the brain sorts and files new information and experiences, and decides how to adapt them. As early as 1968, Bassin concluded that "some of the components of dreams are related to the unconscious processing of information. "If this were so, we would expect that the more new information presented during the day, the higher the proportion of sleep devoted to dreaming, i.e. REM sleep.

This turns out to be the case. Whereas adults may average 20% of their sleep in the REM sleep state this decreases as they grow older - but very young children, who are subjected to the highest proportion of new information and experiences, actually spend up to 50% of their sleep in the REM phase.

We certainly know that depriving people of sleep can have a catastrophic effect on their mental ability. In a very public demonstration of sleep deprivation, a disc jockey in New York elected to stay awake for over 200 hours. His hallucinations during;, the "wakeathon", started out as seeing cobwebs, rabbits and bugs and gradually became serious. He began to imagine that the `: room was on fire (a mysteriously common hallucination in sleep deprivation), and he began to evidence paranoia after 100 hours.

Nicholas Humphrey of Cambridge University believes that dreams act like a dress rehearsal for events we hope or fear may occur. It is as if the brain as computer, is doing a test run on a possible new programme.

Chris Evans goes so far as to say that "we sleep in order to dream" and the theory that these dreams are both a filing and . sorting process, an assimilation of information and a series of dummy runs, coincides well with the views of Dr. Edmond Dewan, a leading sleep researcher at the Air Force Research Laboratories :' in Bedford Massachusetts. He notes that the lower down you go in the evolutionary scale the less the animal sleeps, and therefore can dream. "It is almost impossible to explain the behaviour of the brain during sleep unless some re-programming is taking place". he says.

Mothers of children will testify that during the first few days at primary school, their infants are unusually willing to go to bed. '' They have more novel experiences than usual to review during sleep.

REM sleep has a provable impact on memory, as you would expect. Students at Edinburgh Hospital under the supervision of Dr. Chris Idzikowsky were divided into two groups, and asked to memorise a list of nonsense syllables for 15 minutes in the morning. Half of them were tested in the evening and the other half were tested the next morning, i.e., after sleeping. The group that had slept, scored significantly higher than the first group. "Dreams" says psychologist Patricia Garfield "continue work begun during consciousness".

It should follow that any daytime mental activity that has the deliberate intent of stimulating the subconscious, and the more visually artistically oriented right brain, should precipitate a greater review of that material during REM sleep. In turn that material should be more easily assimilated into the long term memory. Additionally, it should more easily be utilized in the unconscious creative process.

The use of sleep (or more accurately REM sleep) for creativity is well documented. One of the best known is the case of Elias Howe who invented the sewing machine. He had struggled for months to find a way to attach the thread to the needle. One night he dreamed that he was threatened by a group of natives who challenged him to invent the machine or die. As they approached him to thrust their spears into his body, Howe noticed that in the tip of the spear was a eye-shaped hole. Howe awoke instantly with the certainty that it was in the needle end that he should thread the needle.

Robert Louis Stevenson regularly willed himself to dream out the storyline and plot of his novels. He often succeeded and was really one of the first people to programme their dreams deliberately - an activity now receiving widespread attention under the name of "lucid dreaming". He actually conceived of the entire story of Jekyll and Hyde through a series of dreams.

Dr. Morton Schatzman, a psychotherapist, has had considerable success in getting students literally to "dream up" solutions to problems. In one of the simpler tests he gave a series of letters to his students. They were H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O. The letters represent a word he said. Several students reported they had dreams involving water- shark fishing, sailing, swimming, walking in heavy rain. They had subconsciously reached the solution, which was "H to O" or H2O i.e. water.

Sleep Learning (Hypnopaedia)

If sleep helps you to assimilate facts, form opinions, reach solutions, and indulge in a "test run" of behaviour, then can you actually use the period of sleep to learn actively?

Experiments began in the U.S.A. in 1942 and extended to Russia in the 50's. "Hypnopaedia" was a popular idea but there has never been any real success with it.

On the basis of Dr. Chris Evans' work and his conclusion that sleep is when the brain, as computer, is "off line", we can understand why sleep learning has never succeeded. Learning is an activity when fresh information is presented. Sleep is precisely the period when the information is reviewed, not when new data are taken in.

We are now also sufficiently aware of the importance of holistic (left and right brain) learning, that we would not really expect sleep learning to work. Learning may be easiest in a state of calm, relaxed alertness, but that does not mean that you need not be fully conscious.

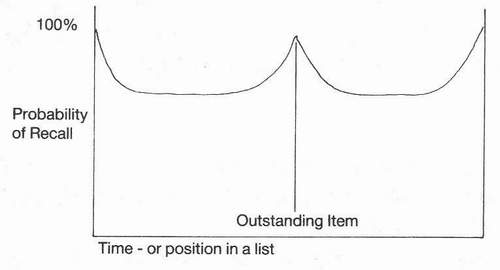

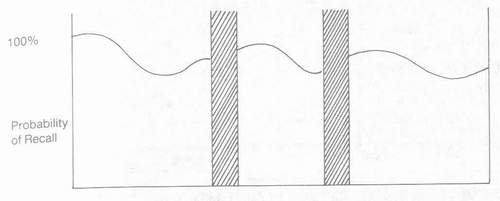

Taking a Break

The popular view that you need to take a break every now and then has been confirmed by French Researcher Henri Pieron. He has found that a planned series of breaks during a study period or lesson increases the probability of recall. A break every 30 minutes is probably optimum, and each break should be of the order of 5 minutes. Certainly no improvement is gained when the break exceeds 10 minutes.

The break should be a complete rest from the type of study being undertaken, otherwise too many competing or interfering associations will be formed, and they will confuse the memory traces laid down in the study period. The deep breathing and relaxation exercises - described in Chapter 12 are specifically designed to produce mental and physical relaxation and enhance oxygen flow to the brain.

The effect of the breaks will be to sustain recall in the way that the diagram opposite shows.

What is at work is the effect of Primacy and Recency coupled with the "Zeigarnik Effect". Zeigarnik, a German researcher, found that interrupting a task, in which a person was involved, even if that task is going well, can lead to appreciably subsequent higher recall.

Review

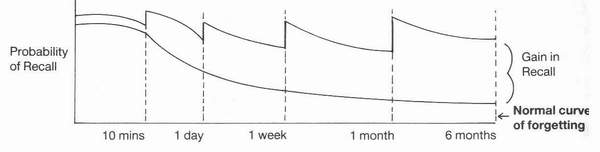

If breaks enhance memory consolidation, there is a similar pattern that significantly enhances long term memory consolidation, and which dramatically slashes the overall time spent in learning.

From various sources that include Tony Buzans excellent book 'Use your Head', Peter Russell's equally fascinating 'The Brain Book' and from journals of experimental and educational psychology, the following pattern of Review would seem to be ideal. It assumes that initial learning period is up to 45 minutes.

1. Learn material with immediate tests continuously built in to ensure the basic transfer from Short Term to Long Term Memory.

|

Period of Review |

|

| 2. Review after 10 minutes. | 5 mins |

| 3. Review after 1 day | 5 mins |

| 4. Review after 1 week | 3 mins |

| 5. Review after 1 month | 3 mins |

| 6. Review after 6 months | 3 mins |

This pattern of review will necessitate about 20 minutes of time per 45 minutes of initial learning, but will conservatively save many hours of learning compared with the normal instinctive urge which is to "learn it all in one go".

The pattern and its effect can be pictorialised as follows:

The constant boost to recall contrasts with the typical curve of forgetting we could expect with review. It would not be optimistic to expect a 400-500% boost in learning from this learning plan.

In a unique study reported in "Practical Aspects of Memory" Mangold Linton kept a diary over a four year period. She was able to show that those events in the diary which she never reviewed were 65% forgotten. Even a single review cut down forgetting significantly, whereas four reviews over a four year period reduced the probability of forgetting down to a level of about 12%. Put positively, just 4 reviews could produce an 88% probability of recall!

Your memory and your ability to learn are much, much greater than you have supposed.

Yet we have not even begun to discuss the biggest single aid to fast and effective learning - the enormous power of association. Before we do, let us turn our attention from natural actions that aid memory, to some artificial but valuable and instructive aids.