11. Putting It All Together

In the four years it took to research this book we learnt a great deal about the mind, memory and learning. Quite deliberately we approached it from the psychologist's standpoint rather than the existing educator, because this was more likely to produce the fresh thinking that every genuine breakthrough must have.

The time has come to recap on what we have learnt. In doing so, some important principles will emerge. These principles direct us towards an ideal learning programme. They also pinpoint how it is possible to improve upon the proven success and strength of the Lozanov method.

For reasons that are given later, we have made some of our conclusions relevant to the teaching of languages - since this is the least easy learning situation of all.

What we learned

1. Your brain has enormous potential. It is capable of much more than you have imagined. In fact the more you use it the more associations and connections you make and the easier it is to remember and learn yet more new material. A rich, stimulating environment is the main factor in achieving full potential in youngsters and preventing deterioration in old age.

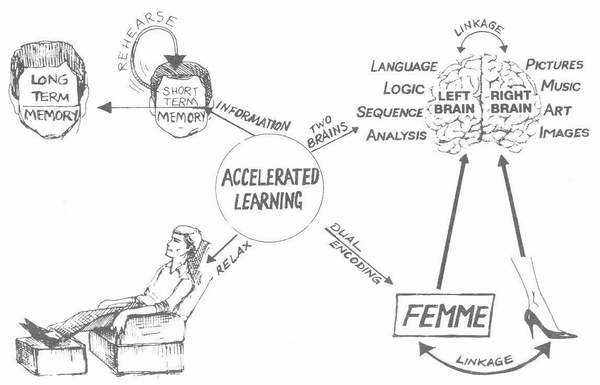

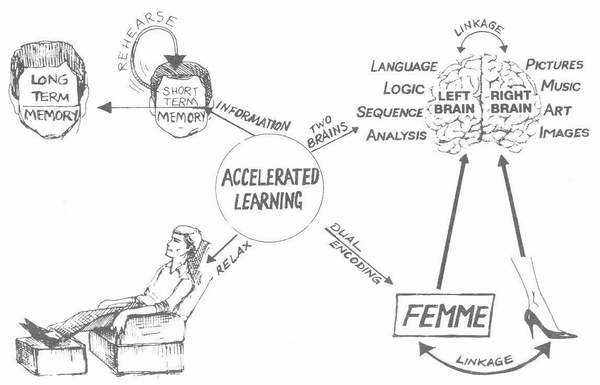

2. The left and right halves of the brain process information in somewhat different ways. The right brain responds to art, music and patterns - it processes information holistically, grasps the whole picture quickly and is more sensitive to subconscious influences. The left brain tends to work on a step by step basis. Yet most existing teaching is directed to the left brain.

Fully involve the right brain and you don't just double your brain power, you increase it many times over.

3. Relaxation is important to create a stress free learning environment and conditions of ideal receptivity. Relaxation is associated with a predominantly Alpha brain wave pattern. Relaxation releases energy for learning.

4. All new information enters the short term memory store, but only gets transferred to the long term memory store if it is rehearsed immediately.

5. Registering new facts depends on strong encoding, strong encoding depends to a large extent on creating strong associations.

Strong encoding is achieved by creating concrete images of sights, feelings, sounds, taste and smell. The stronger the original encoding the better the ultimate recall - just as the better the index, the more usable is the library.

Recall is essential to learning and recall is different to, and less easy to achieve than, recognition.

6. Words linked to pictures are easier to learn/remember because you have achieved dual encoding. Recall depends on association, linking ideas together in a pattern.

7. Visual memory is essentially perfect. The key to memory (and learning) is, therefore, to improve your visualisation and to form strong visual associations for new material. Interactive visual images are the most powerful. That's the lesson from mnemonics.

8. Basically the more time you spend learning the better the learning. However, the way the time is deployed is highly influential. `Distributed practice' is the optimum strategy. An ideal learning pattern would involve:

Such a schedule can maintain recall at up to 88% - four times better than the expected curve of forgetting.

9. Individual lessons should have breaks. It utilises the Primary, Recency and Zeigarnik effects.

10. Lessons should ideally incorporate something outstanding in the middle to raise arousal - the "Von Restorf" effect.

11. Teach the specifics first - in languages the descriptive nouns and verbs are easiest to learn.

12. The mind naturally imposes organisation on new material and groups ideas or words together. This process helps memory. Even sorting words out into categories is a significant memory aid. (Tulving)

13. Learning the principle is easier than learning each individual example. (Teach bad speller to visualise).

14. Meaning is vital to memory - which is why nonsense phrases are so difficult to learn. There is no relationship available.

15. Context is important. It provides an overview a 'map' of what you will learn and facilitates meaning. A jigsaw is easier to do if you can see the whole picture.

16. Learning by example is better than learning by rote - but the more general the examples the easier it is to apply the knowledge later in a broad set of circumstances.

17. Chunking is an important aid to memory.

18. Rhythm and Rhyme are important aids to memory. They stir body reaction and they are a form of organised pattern which makes it easier to remember.

19. Music, especially Baroque Music, is an ideal accompaniment to new material. It ensures left/right brain linkage, creates an auditory and rhythmic association with the material, creates an emotive link with the material and simultaneously promotes a state of relaxed awareness, by "leading".

20. Memory works by creating a network of associated ideas. A Memory Map reproduces very closely the way in which the brain works - so it facilitates learning.

21. Individual words are less easy to remember than ideas or sentences, which are again forms of organisation, so linking words together helps. Hence it is easier to learn a language via stories - each new word building on, and linking to, the vocabulary already learned.

22. We probably all have the potential for photographic memory. The key to it is imagination.

23 Suggestion can improve actual performance greatly - not by creating new abilities but by unblocking the negative suggestion that something cannot be done.

These negative suggestions are often formed in childhood. When a suggestion is implanted in the subconscious mind, the subconscious mind will find a way of bringing it about.

Suggestion is a powerful tool for learning. Creating a belief in success and a positive self-image, will, when allied to a sound and realistic learning programme, create great success. The subconscious mind appears to be controlled by the limbic system and is best accessed and influenced, not by left brain logic, but by an approach that incorporates an emotive appeal.

24. Learning is maximised when all the elements are focussed on the learning process. Since possibly up to 90% of communication is at the subconscious level, the greater the number of subconscious stimuli that are orchestrated to aid learning, the faster and more effective is that learning. Such learning has been characterised as intuitive learning. Some

ways this can be achieved (in a language course for example) are:

25. Imaging and articulation of new material is a powerful memory creating device.

26. Presenting each lesson to the student in the three sensory channels - Visual, Auditory and Kinaesthetic - ensures that the presentation is in a style in which the student learns best, and that all three senses are co-ordinated to make learning highly effective. It also enables the student to deliberately extend the use of his senses.

27. The above programme ensures early success and thus provides the motivation for extra attention and involvement. This fuels a virtuous circle.

We are almost ready to draw our conclusions together and to describe an Accelerated Learning procedure that will work for you at home, in your business life, and to help your child progress at school.

The method will work for any subject - maths, English literature, geography, history, physics. We have chosen, however, to describe the techniques as it applies to languages, since learning a language is the most demanding of alI learning situations.

We have seen that no learning can take place without memory and memory depends to a great extent on creating strong

associations. A memorable event in your life is invariably linked or associated with a physical feeling and/or with a strong visual image, and/or with your surroundings at the time. The reason why scientists who research memory, routinely use nonsense phrases in their experimental work, is that such phrases, by definition, do not mean anything. They, therefore, trigger no associations in the mind. Consequently nonsense phrases are the least easy things to memorise.

At the beginning a foreign language is rather like a list of nonsense phrases. There are no associations to `hook' on to.

The importance of association in language is easy to demonstrate. For example, the German for dog is HUND. that is an easy word to learn because you have a simple association to the familiar English word HOUND. But you would take longer to learn the German for SUCCESS which is ERFOLG - because it has no linguistic association for you. It triggers no connection.

If Accelerated Learning can boost the speed and effectiveness of learning a language by three or more times, then it will obviously work proportionally even better for other subjects.

Before we finally look at the construction of an actual Accelerated Learning Language Course, it will be helpful to briefly review the works of two people acknowledged as among the world's leading authorities on the teaching of languages. Earl Stevick and Stephen Krashen.

Earl W. Stevick has recently retired as Professor at the School of Language Studies Foreign Service Institute, Arlington, Virginia. His book "Memory, Meaning and Method" which drew together a life time's experience in surveying teaching methods and in practical teaching, has become a classic.

Some of his conclusions are already echoed in this book, but one in particular is worth highlighting.

"Involvement"

Time after time in Stevick's work you came across the overriding importance of involvement. Sometimes he refers to it as `personal investment', sometimes as `depth of processing', but it comes to the same thing - you remember and learn what you became involved in.

There is a Chinese proverb that aptly sums up Stevick's philosophy:

"I forget what I hear

I remember what I see I learn what I do".

We have already referred to the work of Kintsch and Bowen, but Stevick quotes a further study by leading memory researcher J. Craik. Craik gave his subjects a list of words to be learned. He then asked four types of questions.

Each question required the subject to think about the word but at increasing levels of depth. The deeper processing took some little extra time, but the results "were dramatically better" in terms of recall.

Craik ascribes the results to the fact that the extra involvement ensured that the words were indeed passed from the primary or short term memory store into the long term memory.

The message from Craik's work and from this book in general is loud, and it is clear, and it is also good news.

Parrot fashion repetition does not work. It is a superficial use of words. A relaxed involvement in your subject via interesting activities and games that require COMMUNICATION does work. That is the route to Accelerated Learning and it is why, when we devised our Language Programmes, we chose to teach via stories, and by real life dialogues, in which the learner literally acts out the roles.

In a review of learning methods that have incorporated the principle of involvement, Stevick picks out four in particular:

1. Total Physical Response, developed by V. N. Asher, concentrated especially on teaching pupils by commands from the earliest stage. Commands demanded a response and thus involvement. Passivity does not create the best environment for learning - but committed activity does. The more arousal you create in the learner the better. As researcher J. B. Brierly noted `What is important and emotionally charged, is more rapidly embedded than that which is neutral.'

Tests by Kleinsmith and Kaplan as early as 1963, showed that high arousal words were three times better remembered than neutral words - so pairing high arousal words with more neutral words becomes a good strategy in teaching a language. In psychological terms the strategy ensures that the limbic system and the new brain are interacting and that turns on the full power of the brain.

2. "Liberated Spanish" developed by Keith Saucer of Fresno USA. His first step is to teach the vocabulary of disagreement. In this way he automatically engages the involvement of his students, because an argument produces arousal.

3. "Community Language Learning" or C.L.L. developed by leading language researcher C. A. Curran. One of Currans's primary techniques is to create a circle of pupils and a warm friendly atmosphere. He then tape records statements made by the students in the new language. This tape is played back and analysed. The process again automatically involves the

participants since they are listening to their own voices.

Curran is particularly adept at phrasing questions in a way that provokes involvement. Thus "describe Mary" (a character in a story) is not nearly as involving as "say what you like, or what you dislike, about Mary."

4. The Silent Way by Caleb Gattegno, which greatly emphasises the learner and subordinates the role of the teacher. We cannot do justice to the technique here, but in essence, the class is given a very limited initial vocabulary. They would typically be taught the word for a rod (a round coloured piece of wood). Then the teacher acts out all the words while he says the sentence `take the rod' or `give the rod to me' in the target language.

The pupils' task into figure out what the words must mean. The act of figuring it out is involvement.

Subsequently vocabulary is built up by linking new words and ideas on the previously learned vocabulary.

All of the above four teaching approaches, (each one of which is much more sophisticated than the short extract given here may imply), have a common and vital thread. They demand involvement. If you want to learn fast and learn well, you must achieve the same.

There is, finally, one other specialist sense in which you need to involve yourself in learning a language - one to which Peter O'Connell had already referred. Your own language and nationality is very much bound up with your sense of identity, your ego. Unfortunately to integrate too completely with a new culture can be threatening.

H. W. Seligen writing in "Language Sciences" in 1975 noted that people who learned to pronounce a new language with the least accent tended to have had few friends in their immediate peer group as children. They were, therefore, quite happy to take on a new identity. Revealingly actor Peter Sellers alluded to the same factor when he was asked to comment on his outstanding ability for mimicry.

If you are generally sensitive to the feelings of others you will find the acquisition of a good foreign accent comparatively easy. `Empathy' notes Psychologist A. Z. Guiora `predicts pronunciation ability.' The more rigid the personality, the less easy it is to acquire an authentic accent.

The way to achieve a good accent is to involve yourself (that word again!) in the role of a character in your new language, imagining how he or she would feel and talk, using appropriate gestures and facial expressions. Return to a childlike readiness to be receptive, adaptive and spontaneous, and you'll succeed, not just in learning the vocabulary, but in learning the accent too.

----------------