Lords of the World, Blackie & Son, London, 1898

THE Melcart, the sacred ship of Carthage, was on its homeward voyage from Tyre, and had accomplished the greater part of its journey in safety; in fact, it was only a score or so of miles away from its destination. It had carried the mission sent, year by year, to the famous shrine of the god whose name it bore, the great temple which the Greeks called by the title of the Tyrian Hercules. This was too solemn and important a function to be dropped on any pretext whatsoever. Never, even in the time of her deepest distress, had Carthage failed to pay this dutiful tribute to the patron deity of her mother-city; and, indeed, she had never been in sorer straits than now. Rome, in the early days her ally, then her rival, and now her oppressor, was resolved to destroy her, forcing her into war by demanding impossible terms of submission. Her old command of the sea had long since departed. It was only by stealth and subtlety that one of her ships could hope to traverse unharmed the five hundred leagues of sea that lay between her harbour and the old capital of Phoenicia. The Melcart had hitherto been fortunate. She was a first-rate sailer, equally at home with the light breeze to which she could spread all her canvas and the gale which reduced her to a single sprit-sail. She had a picked crew, with not a slave on the rowing benches, for there were always freeborn Carthaginians ready to pull an oar in the Melcart. Hanno, her captain, namesake and descendant of the great discoverer who had sailed as far down the African coast as Sierra Leone itself, was famous for his seamanship from the Pillars of Hercules to the harbours of Syria.

The old man—it was sixty years since he had made his first voyage—was watching intently a dark speck which had been visible for some time in the light of early dawn upon the north-western horizon. "Mago," he said at last, turning to his nephew and lieutenant, "does it seem to you to become bigger? your eyes are better than mine."

"Not that I can see," answered the young man.

"She hardly would gain upon us if she has no more wind than we have. Well, I shall go below, and have a bite and a sup."

He wetted his finger and held it up. "It strikes me," he went on, "that the wind, if you can call it a wind, has shifted half a point. Tell the helmsman to put her head a trifle to the north. Perhaps I may have a short nap. But if anything happens, call me at once."

Something did happen before ten minutes had passed. When Mago had given his instructions to the helmsman, and had superintended a slight shifting of the canvas, he looked again at the distant ship. It had become sensibly larger. The wind had freshened out at sea, and was rapidly bringing the stranger nearer. Mago hurried below to rouse his uncle. The old man was soon up on deck.

"I wish we were ten miles nearer home," he muttered, after taking a long look into the distance. "Get the oars out. If she is an enemy, and wants to cut us off, half a mile may make all the difference."

The order was promptly obeyed, and the rowers bent to their work with a will. But all the will in the world could not make the Melcart move very fast through the water. She was stoutly built, as became a ship that had to carry a precious burden through all weather, and she was foul with the long voyage. The goal of the race between her and the stranger, which could now be seen to be a Roman ship-of-war, was a headland behind which, as Hanno knew, was the harbour of Chelys. Let her reach that and she was safe. But it seemed as if this was not to be. The Roman ship had what wind there was right aft, and, notwithstanding all the efforts of the Melcart's crew, moved more rapidly through the water. She would manifestly cut off the Melcart before the headland was reached. But Hanno was not yet at the end of his resources.

"Call Mutines," he said to his lieutenant.

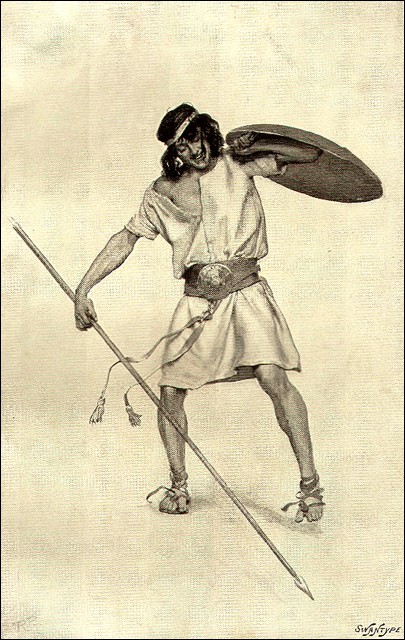

Mutines was a half-caste Carthaginian, whose thick lips, flat nose, and woolly hair indicated a negro strain in his blood. "Mutines," said the old man, "you used to have as good an aim with the catapult as any man in Carthage. If your hand has not lost its cunning, now is the time to show your skill. Knock that rascal's steering-gear to pieces, and there is a quarter-talent for you."

"I will do my best, sir," said Mutines; "but I am out of practice, and the machine, I take it, is somewhat stiff."

The catapult, which was of unusual size and power, had been built, so to speak, into the ship's forecastle. It could throw a bolt weighing about 75 lbs., and its range was 300 yards. While Mutines was preparing the engine, word was passed to the rowers that they were to give six strokes and no more. That, as Mutines reckoned, would be enough to bring him well within range of the enemy. The calculation was sufficiently exact. When the rowers stopped, the two ships, having just rounded the headland, were divided by about 350 yards. The impetus of the Melcart carried her over about 100 more. When she was almost stationary Mutines let fly the bolt. He had never made a happier shot. The huge bullet carried away both the tillers by which the steering paddles were worked. The ship fell away immediately, and the Melcart, for whose rowers the fugleman set the liveliest tune in his repertory, shot by, well out of range of the shower of arrows which the Roman archers discharged at her. In the course of a few minutes she had reached the harbour of Chelys.

But her adventures were not over. The captain of the Roman ship was greatly enraged at the escape of his prey. To capture so famous a prize would mean certain promotion, and he was not prepared to resign his hopes without an effort to realize them. As soon as the steering-gear had been temporarily repaired, he called his sailing-master, and announced his intention of following the Carthaginian into the harbour.

The man ventured on a remonstrance. "It's not safe, sir," he said; "I don't know the place, but I have heard that the water is shallow everywhere except in the channel of the stream."

"You have heard my orders," returned the captain, who was a Claudius, and had all the haughtiness and obstinacy of that famous house. The sailing-master had no choice but to obey.

Chelys, so called from the fancied resemblance of its site to the shape of a tortoise, was a small Greek settlement which lay within the region dominated by Carthage. It was a place of considerable antiquity—older, its inhabitants were fond of asserting, than Carthage itself. For some years it had maintained its independence, but as time went by this position became more and more impossible. Had Chelys possessed any neighbours of the same race, a league might have given her at least a chance of preserving her freedom. But she stood absolutely alone, surrounded by Phœnician settlements, and she had no alternative but to make her submission to her powerful neighbour. She obtained very favourable terms. She was free from tribute, no slight privilege, in view of the enormous sums which the ruling city was accustomed to exact from her dependencies. She was allowed to elect her own magistrates, and generally to manage her own affairs. To contribute a small contingent to the army and navy of the suzerain state was all that was demanded of her. It was natural, therefore, that Chelys should be loyal to Carthage—far more loyal, in fact, than most of that city's dependencies. Rome, which had more than once exacted a heavy sum as the price of the little town's immunity from ravage, she had no reason to like.

The incident described above had taken place within full view of the piers and quays of Chelys. The excited population which crowded them had hailed with an exulting shout the fortunate shot that had crippled the Roman vessel, and had warmly welcomed the Melcart as she glided into the shelter of the harbour. Their delight was turned into rage when it became evident that the enemy was intending to pursue her. The insolent audacity of the proceeding excited the spectators beyond all bounds. Stones and missiles of all kinds were showered upon the intruders. As the ship was within easy range of the quays on both sides of the harbour, which was indeed of very small area, the crew suffered heavily.

Claudius perceived that he had made a mistake, and gave orders to the rowers to back, there not being space enough to turn. It was too late, and when a huge pebble, aimed with a fatal accuracy, struck down the steersman from his place, the doom of the Melicerta—for this was the name of the Roman ship—was sealed. A few moments afterwards she grounded.

This was, of course, the signal for a determined attack. Hundreds of men waded through the shallow water and climbed over the bulwarks. The crew made a brave resistance, but they were hopelessly outnumbered and were cut down where they stood. The magistrates of the city happened to be in consultation in the town-hall. Disturbed in the midst of their deliberations by the sudden uproar they hurried down to the waterside, but were too late to save any but a very few lives. Claudius had stabbed himself when he saw how fatal a mistake he had made.

Chelys was, of course, in a tumult of delight at its brilliant success in destroying a Roman ship-of-war. Its responsible rulers, however, were very far from sharing this feeling. A defenceless city, and Chelys was practically such, for its walls, never very formidable, had been suffered to fall into decay, must take no part in the hostilities of a campaign. So long as it observes this neutrality it is really better off than a fortified town, but to depart from this policy is sheer madness.

The magistrates did all they could. They sent back the few prisoners whom they had been able to rescue from the hands of the populace, to the commander of the squadron to which the Melicerta had belonged. They offered to pay an indemnity. They went so far as to promise that the ringleaders of the riot should be handed over for trial. The Roman admiral, a Flaminius, and so belonging to a family that had more than once made itself notorious for unusual brutality, would not hear of making any conditions. He determined upon a vengeance which was not the less pleasing because it would be as lucrative as it was cruel. Chelys was to be visited with the severest penalty known in warfare—all the male inhabitants of the military age and over were to be put to death, the women and children were to be sold as slaves. The slaves from Chelys, as Flamininus, a shrewd and unscrupulous man of business knew, would fetch a high price. They were Greeks, if not of the purest blood, and while barbarians in any number could be easily obtained, Greek slaves were a rare article in the market.

His resolve once taken, Flamininus took every precaution that its execution should be as complete as possible. The magistrates, who had come to intercede for their countrymen, were detained; no hint of what was intended was allowed to reach the doomed city. Landing the half legion of marines which the squadron carried he occupied in irresistible force Chelys and all the roads by which it could be approached or left. His next step was to make what may be called an inventory of the prey which had fallen into his hands. The census roll of citizens was seized, and information about their families was purchased from some prisoners who were willing thus to redeem their lives. A few wealthy men and women were allowed to ransom themselves at the highest prices that could be extorted from their fears; and then, when a few days had been allowed for the assembling of the slave-dealers, who, with other animals of prey, human and non-human, followed the armies and fleets of Rome, Flamininus allowed the deputation to return, and proceeded to execute his sentence.

THE wealthiest, best-born, and generally most influential citizen in Chelys was Lysis, son of Cleanor, father himself of another Cleanor, so named, according to a custom common in Greek families, after his grandfather. He was descended in a direct line from the original founder of the settlement, an Ephesian Greek, and was also distinguished by the possession of the hereditary priesthood of Apollo. The family prided itself on the purity of its descent. The sons sought their brides among four or five of the noblest Ephesian families. The general population of Chelys, though still mainly Hellenic in speech and habits of life, had a large admixture of Phœnician blood, but the house of Lysis could not be reproached with a single barbarian misalliance.

Lysis had been the leader and spokesman of the deputation which had vainly approached the Roman commander. His house, in common with all the principal dwellings in the town, had been occupied by the Roman marines.

But a douceur, judiciously administered to the sub-officer in command, had procured for him the privilege of a brief period of privacy. He found that his wife and children were still in ignorance of the Roman admiral's decision. They did not, indeed, expect any very lenient terms—they looked for a fine, that would seriously cripple their means; but they were not prepared for the brutal reality. Lysis tasted for the first time the full bitterness of death when he had to dash to the ground the hope to which they had clung.

"Yes," he said in answer to a question from his wife, unable or unwilling to believe her ears; "yes, it is too true—death or slavery."

Dioné—this was the wife's name—grew pale for a moment, but she summoned to her aid the courage of her house—she claimed to be descended from the great Ion himself, the legendary head of the Ionic race—and recovered her calmness. Stepping forward, she threw her arms round her husband's neck. Her first thought was for him; her second, scarcely a moment later, for her children.

"And these?" she said.

Recovering himself with a stupendous effort of self-control, Lysis spoke.

"Listen; the time is short, and there are grave matters to be settled. It was hinted to me, and more than hinted, that I might purchase your life, Dioné, and my own. These Romans are almost as greedy for money as for blood. What say you?"

"And these?" said the woman, pointing to her children, while her cheek flushed and her eyes brightened with the glow of reviving hope. "Can they also be ransomed?"

"That is impossible," said Lysis.

"Then we will die."

"That is what I knew you would say, and I gave the fellow—it was the admiral's freedman who spoke to me about the matter—the answer, 'No', without waiting to ask you. Our way is clear enough. My father learnt from the great Hannibal the secret of his poison-ring, and he handed it on to me. You and I can easily escape from these greedy butchers, but our children—" He struggled in vain to keep his self-command. Throwing himself on a couch hard by, he covered his face with his cloak.

The children were twins, very much alike, as indeed twins very commonly are, and yet curiously different. Apart, they might easily have been mistaken for each other, supposing, of course, that they dressed alike; seen together, any one would have said that such a mistake would hardly be possible, so great was the difference in colour and complexion—a difference that impresses the eye much more than it impresses the memory. But whatever dissimilarity there was accidental rather than natural. Cleanor had been seized at a critical period of his growth with a serious illness, the result of exposure in a hunting expedition. This had checked, or more probably, postponed his development. His frame had less of the vigour, his cheek less of the glow of health than could be seen in his sister's, of whom, indeed, he was a somewhat paler and feebler image.

"We will die with you," said the twins in one breath. They often spoke, as, indeed, they often thought, with a single impulse.

"Impossible again!" said Lysis. "The priesthood which, as you know, I inherited from my fathers, I bound, under curses which I dare not incur, to hand on to my son. If the gods had made me childless—and, for the first time in my life, I wish that they had—I must have adopted a successor. This, indeed, I have done, to provide for the chances of human life; but you, Cleanor, must not abdicate your functions if it is in any way possible for you to perform them. And then there is vengeance; that is a second duty scarcely less sacred. If you can live, you must, and I see a way in which you can."

"And I see it too," cried the girl, with sparkling eyes. "Cleanor, you and I must change places. You have sometimes told me that I ought to have been the boy; now I am going to be."

"Cleoné!" cried the lad, looking with wide eyes of astonishment at his sister; "I do not know what you mean."

"Briefly," replied the girl, "what I mean is this. You masquerade as a girl, and are sold; I masquerade as a man, and am killed."

"Impossible!" cried the lad; "I cannot let you die for me."

"Die for you, indeed!" and there was a touch of scorn in her voice. "Which is better—to die, or be a slave? Which is better for a man? You do not doubt; no one of our blood could. Which is better for a woman? It does not want one of our blood to know that. The meanest free woman knows it. By Castor! Cleanor, this is the one thing you can do for me. Die for you, indeed! You will be doing more, ten thousand times more, than dying for me!"

"She is right, my son," cried Lysis. "This was my very thought. Phœbus, the inspirer, must have put it into her heart. Cleanor, it must be so. This is your father's last command to you. The gods, if gods there are—and this day's work might make doubt it—will reward you for it. But the time is short. Hasten, and make such change as you need."

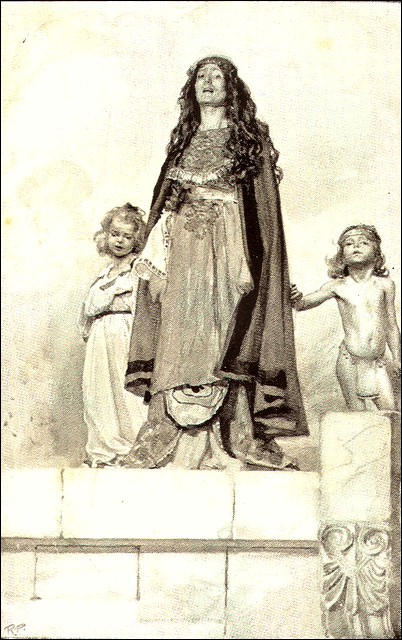

The twins left the chamber. When they returned, no one could have known what had been done, so complete was the disguise which Cleoné's skilful fingers had effected. The girl's flowing locks, which had reached far below her waist, now fell over her Shoulders, just at the length at which it was the fashion of the Greek youth to wear them, till he had crossed the threshold of manhood. His were rolled up, maiden-fashion, in a knot upon his head. She had dulled her brilliant complexion by some pigment skilfully applied. His face, pale with misery, needed no counterfeit of art.

Lysis and his wife had gone. By a supreme effort of self- sacrifice they had denied themselves the last miserable solace of a farewell, and were lying side by side, safe for ever from the conqueror's brutality. While Cleanor and his sister waited in the expectation of seeing them, a party of marines entered the room.

"Fasten his hands, Caius," said the sub-officer to one of his men, "and firmly too, for he looks as if he might give us trouble. By Jupiter! a handsome youth! What a gladiator he would make! Why do they kill him in this useless fashion? The girl is your business, Sextus. Be gentle with her, but still be on your guard, for they will sometimes turn. But she looks a poor, spiritless creature."

THE fate of Chelys caused wide-spread indignation and disgust even among the enemies of Carthage. No one was more indignant than Mastanabal, King Masinissa's second son. The prince had tastes and habits very uncommon in the nation of hunters and fighters to which he belonged. He was a lover of books, and disposed to be a patron of learning, if he could only find learning to patronize. The Greek population of Chelys had always preserved some traces of culture, and the Numidian prince was on terms of friendship with the settlement. He was an occasional visitor at its festivals, had received the compliment of a crown of honour, voted to him in a public assembly, and had shown his appreciation of the distinction by building for the community a new town-hall.

His intercession had been implored by the magistrates when they found themselves repulsed by the commander. Unfortunately he was absent home when their messenger arrived. Immediately on his return he hurried to the spot. Too late, even if it had in any case been possible, to hinder the brutal vengeance of Flamininus, he was yet able to mitigate the lot of the survivors. By pledging his credit to the slave-dealers, themselves disposed to accommodate so powerful a personage, he was able to secure the freedom of all the captives.

He made special inquiries about the family of Lysis, whose hospitality he had always enjoyed during his visits to the town, and learnt enough to induce him to make a personal inspection of the captives. As the melancholy procession passed before him, his keen eyes discovered Cleanor under his disguise. He had, of course, too much delicacy and good taste to inflict upon him the pain of a public recognition. The young man was transported u a closed litter to a hunting-lodge that belonged to the prince. Here he found himself an honoured guest. His personal wants were amply supplied; a library of some extent was at his disposal; and the chief huntsman waited upon him every morning to learn his pleasure in case he should be disposed for an expedition.

In the course of a few days a letter from the prince was put into his hands. Beginning with a tactful and sympathetic reference to his misfortunes, it went on thus:

Use my home as if it were your own for as long as you will. You cannot please me better than by pleasing yourself. But if you are minded to find solace for your sorrows in action—and to this I would myself advise you proceed to Cirta, and deliver the letter which I inclose herewith to the king, my father. My steward will provide you with a guide and an escort, and will also furnish such matters of dress and other equipment as you may need. Farewell!

Cleanor's resolution was taken at once. In the course of a few hours he was in the saddle. Two days of easy travel brought him to Cirta, and he lost no time in presenting himself at the palace of King Masinissa. His letter of introduction, bearing as it did the seal of Prince Mastanabal, procured for him instant admission. The major-domo of the palace conducted him to a guest- chamber, and shortly afterwards one of the king's body-guard brought him a message that Masinissa desired to see him as soon as he had refreshed himself after his journey.

The chamber into which the young Greek was ushered was curiously bare to be the audience-room of a powerful king. The walls were of mud roughly washed with yellow; it was lighted by two large openings in the walls, unglazed, but furnished with lattices which could be closed at will by cords suspended from them; the pavement was of stone, not too carefully smoothed; for furniture it had a sideboard, with some cups, flagons, and lamps upon it, a table, two or three chairs for the use of visitors who were accustomed to these comfortless refinements, and a divan piled up with bright-coloured mats and blankets. Near the divan was a brazier in which logs were smouldering.

Masinissa, king of Numidia, was a man whose intellect and physical powers were alike remarkable. He had consolidated the wandering tribes of Northern Africa into a kingdom, which he had kept together and aggrandized with a politic firmness which never blundered or wavered. His stature, though now somewhat bowed with years, was exceptional. His face, seamed with a thousand wrinkles, and burnt to a dark red by unnumbered suns, the snowy whiteness of hair and beard, and the absolute emaciation of his form, on which not a trace of flesh seemed to be left, spoke of extreme old age. And indeed he had more than completed his ninetieth year, an age not phenomenally rare among us, where the climate and the habits of life are less exhausting, but almost unheard of in a race whose fervid temperament seems to match their burning sky.

The old man's strength was now failing him. Two years before, he had commanded an army in the field, and commanded it with brilliant success, routing the best troops and the most skilled generals that Carthage could send against him. He was not one of the veterans who content themselves with counsel, while they leave action to the young. That day he had remained in the saddle from sunrise to sunset, managing without difficulty a fiery steed, whose saddle was no seat of ease. He had showed that on occasion he could deal as shrewd a blow with the sword, and throw as straight a javelin, as many men of half his age. But at ninety years of age two or three years may make a great difference. Masinissa had fought his last battle. His senses were as keen as ever, the eyes flashed with their old fire, but his breathing was heavy and laboured, and his hands shook with the palsy of age.

"Welcome, Cleanor!" he said with a full resonant voice that the years had not touched, "my son commends you to me. Can you be content to wait on an old man for a month or so? I shall hardly trouble you longer. I have never been a whole day within doors save once for a spear wound in the throat, and once when they tried to poison me; and those who have lived in such fashion don't take long dying."

Cleanor found his task an easy one. The old king suffered little, except from the restlessness which comes with extreme exhaustion. Even over this he maintained a remarkable control. It was not during his waking hours, but in his short periods of fitful slumber, that the uneasy movements of his limbs might be observed. His intelligence was as keen as ever, and his memory curiously exact, though it was on the far past that it chiefly dwelt. What a story the young Greek could have pieced together out of the old man's recollections? He had seen and known the heroes of the last fierce struggle between Carthage and Rome, had ridden by the side of the great Scipio at Zama, and had been within an ace of capturing the famous Hannibal himself as he fled from that fatal field. The young Greek, surprised to find himself in such a position, was naturally curious to know why the old man preferred the companionship of a stranger to that of his own kindred. When he ventured to hint something of the kind, the king smiled cynically.

"You don't understand," he said, "the amiable ways of such a household as mine. What do you think would have been the result if I had chosen one of my three sons to be with me now? Why, furious jealousy and plots without end on the part of the other two. And if I had had the three of them together? Well, I certainly could not have expected to die in peace. Quarrel they certainly will, but I can't have them quarrelling here. Mind, I don't say that they are worse than other sons; on the contrary, they are better. I do hope they may live in peace when I am gone; at least, I have done my best to secure it."

As the days passed, the king grew weaker and weaker, but his faculties were never clouded, and his cheerfulness was unimpaired.

About ten days after the conversation recorded above, a Greek physician, whose reputation was widely spread in Northern Africa, arrived at the palace. The three princes had sent him. Masinissa, informed of his coming, made no difficulty about seeing him. "I am not afraid of being poisoned," he said with a smile;" I really do not think that my sons would do such a thing. It would not be worth while, and, anyhow, they could not agree about it. Yes, let him come in. Of course he can't do me any good; but it is one of the penalties to be paid for greatness, that one must die according to rule. No one of any repute is allowed to die in these parts without having Timaeus to help him off. Yes, I will see him. And mind, Cleanor, when he has examined me have a talk with him, and make him tell you the absolute truth."

That afternoon after the physician had departed, the king summoned the young Greek to his chamber.

"Well, what doe she say, Cleanor?" he asked.

The young man hesitated.

"Come," cried the old king, raising his voice. "I command you to speak. As for these physicians, it is quite impossible for a patient to get the truth out of them. It seems to be a point of honour not to tell it. But I suppose he told it to you. Speak out, man; you don't suppose that I am afraid of what I have faced pretty nearly every day for nearly fourscore years."

"He said," answered Cleanor in a low voice, "that your time, sire, was nearly come."

"And how many days, or, I should rather say, hours did he give me?"

"He said that you could hardly live more than two days."

"Well, I am ready. I have had my turn, a full share of the feast of life, and it would be a shameful thing if I was to grudge to go. But there is trouble ahead for those who are to come after me. I have done my best for my kingdom, yet nothing can save it long. You know, I had to choose, when I was about your age, between Rome and Carthage, and my choice was the right one. If I had taken sides with Carthage, Rome would have swallowed up this kingdom fifty years ago; as it is, she will swallow us up fifty years hence. Sooner or later we are bound to go. But it has lasted my time, and will last my sons' time too, if they are wise. And now, as to this matter. I have something to put in your charge. You have heard of Scipio?"

Cleanor nodded his assent.

"He came over here some two months ago, when I had had my first warning that my time was short, and that I had best set my affairs in order. No one had any notion but that he came on military business. The Romans had asked me for help, and I didn't choose to give it just then. They hadn't consulted me in what they had done, and it was time, I thought, that they should have a lesson. We did discuss these matters; but what he really came for was a more serious affair. I left it to him to divide my kingdom between my three sons. I had thought of dividing it in the usual way; this and that province to one, and this and that province to another. But he had quit another plan in his head, and it seemed to me wonderfully shrewd. 'Don't divide the kingdom,' he said; 'the three parts would be too weak to stand alone. Divide the offices of the kingdom. Let each prince have the part for which he is best fitted—one war and outside affairs, another justices, and a third, civil affairs.' Well I took his advice, and had this settlement put in writing. The chief priest of the temple of Zeus in Cirta here has the document in his keeping."

After this the old man was silent for a time. Rousing himself again, for he had been inclined to doze, he said:

"Cleanor, are you here?"

"Yes, sire," replied the Greek.

"Don't leave me till all is over. And now give me a cup of wine."

"But sire—the physician said—"

"Pooh! what does it matter if I die one hour or two or three hours before sunrise? And I want something that will give me a little strength."

Cleanor filled a cup and handed it to the king. "It hardly tastes as good as usual," said the old man, when he had drained it, "yet that, I can easily believe, is not the wine's fault, but mine. But tell me, do you think that I shall know anything about what is going on here when I am gone? What does Mastanabal say? I haven't had time to think about these things; but he reads, and you are something of a student too. What do the philosophers say?"

"Aristotle thinks, sire, that the dead may very well know something about the fortunes of their descendants—it would be almost inhuman, he says, if they did not—but that it will not be enough to make them either happy or unhappy."

"Well, the less one knows the better, when one comes to think. To see things going wrong and not be able to interfere! ... But enough of this... And now, Cleanor, about yourself. You do not love the Romans, I think?"

The young Greek's face flushed at the question. "I have no reason to love them, sire."

"Very likely not. Indeed, who does love them? Not I; if I could crush them I would, as readily as I stamp my foot on a viper's head. But that is not the question. Can you make use of them? You shake your head. It does not suit your honour to pretend a friendship which you do not feel. That has not been my rule, as you know, but there is something to be said for it. Well, it is a pity that you can't walk that way. Whether we love them or no, depend upon it, the future belongs to them. And I could have helped you with some of their great men. I have written a letter to Scipio, and two or three others to powerful people in Rome who would help you for my sake. You can deliver them or not as you please. But tell me, what are you going to do if the Romans are out of the question?"

"I thought of going to Carthage," answered the young man in a hesitating voice.

"Carthage!" repeated the king in astonishment. "Why, the place is doomed. It can't hold out more than a year,—or two at the outside. And then the Roman's won't leave so much as one stone standing upon another. They won't run the chance of having another Hannibal to deal with. Carthage! You might as well put a noose round your neck at once!"

"I hope not, sire," said the young man. "And in any case I have only Carthage and Rome to choose between."

"Well," replied the old king after a pause, "you must go your own way. But still I can help you, at least with some provision for the journey. Put your hand under my pillow and you will find a key."

The young man did as he was told.

"Now open that chest in yonder corner, and bring me a casket that you will find wrapped up in a crimson shawl."

Cleanor brought the casket and put it into the king's hands. Masinissa unlocked it and took out a rouleau of gold pieces, which he gave to Cleanor. "That will be useful for the present," he said; "but gold is a clumsy thing, and you can hardly carry about with you what would serve for a single year. This bit of parchment is an order for a thousand ounces of gold—five hundred thousand sesterces in Roman money—on Caius Rabirius, knight, of the Cœlian Hill in Rome, who has kept some money for me for thirty years or more. You can sell the parchment to Bocchar the banker in Cirta here. He will charge you something for his commission, but it will save you trouble. And he will keep the money for you, or whatever part of it you please. It is a very handy way of carrying about money; but there is another that is more handy still."

The old man took out a small leather bag full of precious stones. "These," he said, "you can always hide. It is true that the merchants will cheat you more or less when you want to sell them. Still, you will find these stones very useful."

The jewels were worth at least five times as much as the order on the parchment. "It is too much," murmured the Greek. "I did not expect—"

"It is true that you did not expect. I have seen that all along, and that is one of the reasons why I give it. And as for the 'too much', you must leave me to judge about that. My sons will find treasure enough when they come to divide my goods between them. I have been saving all my life, and this is but a trifle which they will not miss, and which you will find very useful. And now give me another cup of wine After this I will sleep a while. You will stay,—and don't let that young villain Jugurtha come near me.

Two or three hours afterwards Cleanor was startled to see the old man raise himself in bed, a thing which he had not been able to do without help for three or four days past. He hastened to the bedside, but the king, though his eyes were wide open, did not seem to see him. Yet something there was that he saw; his was no vacant stare, but a look full of tenderness. Then he began to speak, and his voice had a soft tone of which Cleanor could not have believed it was capable.

"So, sweetest and fairest, you have not forgotten me; you, as all men know, no one can forget. Why am I in such haste? Nay, dearest, look in our mirror for an answer. And besides, when you are mine, the Romans can have nothing more to say. Till to- morrow, then—but stay, let me give you a little token. Nay,"—and his voice changed in an instant to a note of horror—"what, pray, has changed my love-gift to this? Faugh!"

And with a gesture as of one who dashed something to the ground, he sank down upon the bed, and in another moment was sleeping again.

Early the next morning the king's three sons, who had heard the physician's report of their father's health, arrived at the palace. Their emotion, as they knelt by the dying king, was genuine, though probably not very deep. The old man was perfectly self-possessed and calm.

"My sons," he said, "I have done my best for you. Probably you will not like it. What is there, indeed, that you would all like? But lay your hands on my head and swear that you will accept what I have done. What it is you had best not know till I am gone. But trust me that I have been just to all of you."

The princes took the oath.

"Cleanor here knows where I have put away my testament, but he is bound by me not to tell till I am buried. And now farewell! Don't wait for the end. You will have your hands full, I warrant, as soon as the tribes know that the old man is gone."

The princes left the room and the old man turned his face to the wall and seemed to sleep. All the rest of that day Cleanor watched, but noticed no change. Just before dawn he heard the sleeper draw two or three deep breaths. He bade the slave who was in waiting in the ante-chamber call the physician.

But the man of science found no movement either of pulse or heart. When he held a mirror to the mouth, there was not the faintest sign of breath upon it. The world had seen the last of one of the most wonderful of its veterans.

THE old king's body was roughly embalmed, in order to give some time before the celebration of the funeral. This was a more splendid and impressive ceremony than had ever been witnessed in that region. The news of Masinissa's death had been carried far into the interior with that strange, almost incredible rapidity with which great tidings commonly travel in countries that have no regular means of communication. The old man had been one of the most prominent figures in Northern Africa for a space more than equal to an ordinary lifetime. Nor had he been one of the rulers who shut themselves up in their palaces, and are known, not in their persons, but by their acts. His long life had been spent, one might say, in the saddle. There was not a chief in the whole region that had not met him, either as friend or as foe. Many had heard from their fathers or grandfathers the traditions of his craft as a ruler and his prowess as a warrior, and now they came in throngs to pay him the last honours. From the slopes of the Atlas range far to the west, and from the south as far as the edge of what is now called the Algerian Sahara, came the desert chiefs, some of them men who had never been seen within the walls of a city. For that day, at least, were suspended all the feuds of the country, many and deadly as they were. It was the greatest, as it was the last honour that could be paid to the great chief who had done so much to join these warring atoms into a harmonious whole.

The bier was carried by representatives of the states which had owned the late king's sway. Behind it walked his three sons; these again were followed by the splendid array of the war- elephants with their gorgeous trappings. The wise beasts, whom the degenerate successors of the old African races have never been able to tame, seemed to feel the nature of the occasion, and walked with slow step and downcast mien. Behind the elephants came rank after rank what seemed an almost interminable cavalcade of horsemen. The procession was finished by detachments of Roman troops, both infantry and cavalry, a striking contrast, with their regular equipment and discipline, to the wild riders from the plains and hills of the interior.

The funeral over, there was a great banquet, a scene of wild and uproarious festivity—a not unnatural reaction from the enforced gravity of the morning's proceedings. Cleanor, who had the sober habits which belonged to the best type of Greeks, took the first opportunity that courtesy allowed of withdrawing from the revel.

He made his way to a secluded spot which he had discovered in the wild garden or park attached to the palace, and threw himself down on the turf, near a little waterfall. The fatigues of the day, for he had taken a great part in the ordering of the morning's ceremonial, and the exhausting heat of the banqueting hall had predisposed him to sleep, and the lulling murmur of the water completed the charm.

When he awoke, he found that he was no longer alone. A stranger in Roman dress was standing by, and looking down upon him with a kindly smile. When the young Greek had collected his thoughts, he remembered that he had already seen and been impressed by the new-corner's features and bearing. Then it dawned upon him that he was the officer in command of the detachment of Roman soldiers that had been present at the obsequies of the king.

And, indeed, the man was not one to be hastily passed over, or lightly forgotten. In the full vigour of manhood—he was just about to complete his thirty-seventh year—he presented a rare combination of strength and refinement. His face had the regularity and fine chiseling of the Greek type, the nose, however, having something of the aquiline form, which is so often one of the outward characteristics of military genius. The beauty of the features was set off by the absence of moustache and beard, a fashion then making its way in Italy, but still uncommon elsewhere. To the Greek it at once suggested the familiar artistic conception of the beardless Apollo.

But the eyes were the most remarkable feature of the face. They expressed with a rare force, as the occasion demanded, kindliness, a penetrating intelligence, or a righteous indignation against evil. But over and above these expressions, they had from time to time a look of inspiration. They seemed to see something that was outside and beyond mortal limits. In after years it was often said of Scipio—my readers will have guessed that I am speaking of Scipio—that he talked with the gods. Ordinary observers did not perceive, or did not understand it. To a keen and sensitive nature, such as Cleanor's, it appealed with a force that may almost be called irresistible. All this did not reveal itself immediately to the young man, but he felt at once, as no one ever failed to feel, the inexplicable charm of Scipio's personality.

"So you too," said the Roman, "have escaped from the revelers?"

Cleanor made a movement as if to rise.

"Nay," said the other, "do not disturb yourself. Let me find a place by you;" and he seated himself on the grass. "What a home for a naiad is this charming little spring! But you will say that a Roman has no business to be talking of naiads. It is true, perhaps. Our hills, our streams, our oaks have no such presences in them. We have borrowed them from you. Our deities are practical. We have a goddess that makes the butter to come in the churn, curdles the milk for the cheese, and helps the cow to calve. There is not a function or an employment that has not got its patron or patroness. But we have not peopled the world of nature with the gracious and beautiful presences which your poets have imagined. Nor, I fancy," he added with a smile, "have your African friends done so."

Cleanor, who would in any case have been too courteous to show to a casual stranger the hostility which he cherished against the Roman nation, felt at once the charm of the speaker's manner. He was struck, too, by the purity of the Roman's Greek accent, and by the elegance of his language, with which no fault could have been found except, perhaps, that it was more literary than colloquial. He laughingly acknowledged the compliment which the Roman had paid to the poetical genius of his countrymen.

A brisk conversation on literary topics followed. Cleanor, who was of a studious turn, had spent a year at Athens, listening to the philosophical teachers who were the successors of Plato at the Academy, and another year at Rhodes, then the most famous rhetorical school in the world. Scipio, on the other hand, was one of the best-read men of his age. He was a soldier and a politician, and had distinguished himself in both capacities, but his heart was given to letters. In private life he surrounded himself with the best representatives of Greek and Roman culture. He now found in the young Greek, with whose melancholy history he was acquainted, a congenial spirit. Cleanor, on the other hand, who had something of the Greek's readiness to look down upon all outsiders as barbarians, was astonished to see how wide and how deep were the attainments of his new acquaintance.

The two thus brought together had many opportunities of improving the acquaintance thus begun. Scipio had to carry out the details of the division of royal functions mentioned in my last chapter. This was not a thing to be done in a day. The three brothers accepted the principle readily enough, though they felt that the one to whom the army had been allotted had the lion's share of power. But when the principles came to be applied there were endless jealousies and differences of opinion. It required all Scipio's tact and personal influence to keep the peace unbroken.

When this complicated business was finished, or at least put in a fair way of being finished, an untoward event cut short Scipio's sojourn in Africa. Two new commanders came out to take charge of the Roman army before Carthage. Scipio knew them to be rash and incompetent, and was unwilling to incur the responsibility of serving under them. Accordingly he asked for permission to resign his command—he held the rank of tribune. The consuls, on the other hand, were not a little jealous of their subordinate's reputation and, above all, of his name. A Scipio at Carthage had a prestige which no one else could hope to rival, and they were glad to get rid of him.

This interruption of an acquaintance which was rapidly ripening into friendship had an important bearing on Cleanor's life. If anyone could have reconciled him to Rome, Scipio was the man. Scipio gone, the old feelings, only too well justified as they were, revived in full force. Hostility to Rome became, indeed, the absorbing passion of his life. It was a passion, however, which he concealed with the finesse natural to his race. For the present his purpose could, he conceived, be better served outside the walls of Carthage than within them. Accordingly he accepted an offer from Mastanabal that he should undertake the duties of a private secretary.

SCIPIO'S forebodings as to the incapacity of the new generals were rapidly justified. The siege operations had not been uniformly successful before they took over the command. There had been losses as well as gains. Still, on the whole, the besiegers had the balance of advantage. The defence had been broken down at more points than one. Carthage was distinctly in a worse position than it had been three months after the breaking out of the war. The besieged had done some damage to the Roman fleet, had burnt a considerable extent of siege-works, and had suffered a distinctly smaller loss in killed and wounded than they had been able to inflict on their assailants.

But if the damage that they suffered was less than that which they did, still it was less capable of being repaired, often indeed could not be repaired at all. If a ship was burnt, they could not build another; the losses of the garrison could not be filled up; the general waste of strength could not be repaired. Carthage, in short, had only itself to draw upon as a reserve; Rome had all the countries that bordered on the Mediterranean, from Greece westward. These were advantages which were certain to tell in the long run, but meanwhile much might occur to delay the final victory.

The first thing to happen in the Roman camp was that supplies began to fall short. The country round Carthage was, of course, so much wasted by this time that practically nothing could be drawn from it. Further off, indeed, there was plenty of food and forage, but the natives showed no readiness in bringing it into camp. The fact was that there was no market; buyers there were in plenty, but not buyers with money in hand, for the military chest was empty, and the pay of the soldiers months in arrear. The consequence of this was that the Roman generals practically raised the siege of Carthage, and devoted their time and strength to reducing the Carthaginian towns, hoping thus to supply their wants. But in this attempt they made very little progress. They began by attacking the town of Clypea. Here they failed. The fleet could not make its way into the harbour, which the towns- people had effectually protected by sinking a couple of ships in the entrance, and the Roman engineers could not reach the walls of the town.

They had better fortune with another small town in the neighbourhood, though their success was gained in a not very creditable way. The towns-people were disposed to come to terms, and a conference between their representatives and the Roman generals was accordingly held. Terms were agreed upon, and the agreement had been actually signed, when some soldiers made their way into the town. The Romans at once broke up the meeting, and treated the place as if it had been taken by storm. This conduct was, of course, as unwise as it was wicked. Next to nothing was gained by the falsehood, while every Carthaginian dependency resolved to resist to the uttermost.

Hippo was the next place to be attacked. After Carthage and Utica—the Roman headquarters were at Utica—Hippo was the largest and most important town in Northern Africa. Its docks, its harbour, its walls were on a grand scale. Two hundred years before, Agathocles, tyrant of Syracuse, in his desperate struggle with Carthage had made it the base of his operations. A lavish expenditure, directed by the best engineers of the time, had made it almost impregnable.

The Roman generals had, indeed, excellent reasons for attacking it. Till it was in their power, they could hardly hope to capture Carthage, for it stood almost between their own headquarters and that city, and commanded the route by which stores had to be carried to the besieging army. But the Roman forces were quite unequal to the undertaking. Twice did the people of Hippo, helped by a sally from Carthage, destroy the siege-works, and when the time for retiring to winter quarters arrived, nothing had been accomplished by the besiegers.

All this did vast damage to the prestige of the Romans. Far- seeing persons were convinced, as I have said, that the future belonged to them; but ordinary observers began to think, and not without some excuse, that their decline had begun. Among these were two out of three sons of King Masinissa. Possibly dissatisfaction had something to do with their state of mind. Each had expected to get more than Scipio's award had given him; both grudged to Gulussa the command of the troops, suspecting that this meant in the end their own subjection to him. Gulussa himself seemed to be still loyal to Rome, but the general discontent had not failed to reach some of the high-placed officers in his army.

Cleanor was still with Mastanabal, and, of course, watched the progress of affairs with intense interest. His hopes rose high when tidings reached the palace that the Romans had abandoned the siege of Hippo. At the evening meal that day the subject was discussed, but in a very guarded way, for the prince was still, at least in name, an ally of Rome, and his young secretary, for this was the office which Cleanor now filled, was too discreet to ignore the fact. The hour for retiring had almost come when the confidential slave who waited on the prince hurriedly entered the chamber and placed a letter in his hands. It was a double tablet closely bound together with cords of crimson silk, these again being secured by seals. Hastily cutting the cords with the dagger which he carried at his waist, the prince read the communication with that impassive and inscrutable look which it is one of the necessities of a despotic ruler to acquire. Rising shortly after from table he bade the young Greek good-night, but added, as if by an after-thought, "But stay, I have a book, a new acquisition, to show you. Come into the library."

The library was a small inner room, of a semi-circular shape, which opened out of the dining-hall. It had this great advantage, contemplated, no doubt, by the builder who designed it, that conversations held in it could not by any possibility be overheard. It had an outer wall everywhere except on the side which adjoined the dining-hall. It was built on columns, so that no one could listen beneath, and there was no storey over it. As long as the outer chamber was empty, absolute secrecy was ensured. Only a bird of the air could carry the matters discussed in it.

"Listen, Cleanor," said the prince, and proceeded to read the following letter:

Hasdrubal, son of Gisco, to King Mastanabal greeting. Know that if you would save Africa, now, and now only, you have the opportunity. The Romans have fled from Hippo fewer by a third than when they first attacked it. Bithyas, commander of Gulussa's cavalry, has come over to us with seven hundred of his best troopers. Strike then along with us such a blow as shall rid us of this devouring Beast now and for ever. Else you shall yourself surely be devoured. Think not that when Carthage is destroyed, there shall be any hope left for Numidia. Farewell!

"What think of this, Cleanor?" the king asked after a pause. "I know well enough that you have no liking for the Romans. Indeed, why should you? But you can judge of how things stand, judge, doubtless, better in some ways than I can, for there many things that we kings never see. Speak frankly. No one can overhear us."

"Sire," replied the young Greek, "it wants, I fear, more wisdom than I possess to give you any profitable counsel. I hate Rome, but I fear her. She makes blunders without number, but always manages to succeed in the end. She chooses mere fools and braggarts for her generals, but always finds the right man at last. So I read her history. There was a time when everyone believed that Hannibal would make and end of her, and yet she survived. She lost army after army, yet conquered in the end. After Flaminius and Varro she found a Scipio. And she has a Scipio now. I saw him, sire, the other day, and felt that he was a great man."

"But he is too young." interrupted the king. "He wants some five years yet of the age when he can be put in chief command."

"True, sire; but when a man is absolutely necessary they will have him, be he young or old."

"Then there is their unending civil strife. What of that?"

"It makes for us, no doubt. But even that they can drop on occasion."

After a pause of some minutes Mastanabal spoke again.

"Then, what do you advise?"

"Sire," replied the young Greek, "I would advise you for the present to do nothing. Let me answer this letter in person, and answer it as I think best, if you can trust me so far. I have a plan, for I have been thinking of these matters night and day. But don't ask me what it is. It is better that you should know nothing about it. I will start at once. It might look well if you were to send some troopers in pursuit. Of course they must not catch me. Put Juba in command, and we may rely on their not being too active."

"Will you carry any token from me?" asked the king.

"No, sire, it is better not. Let me have the letter; that will be enough. Will you forgive me if I steal Whitefoot from her stable?"

"Take her or any other horse that you want. Have you money enough?"

"Ample, sire; your good father provided me with that."

"Then, farewell! You make me curious, but I suppose that I may not ask any questions. In any case, and whatever happens, count me as a sure friend."

Before midnight Cleanor was well on his way to Carthage. At the first signs of dawn he drew rein, and halted for the day at a small cluster of palms, where there was abundance of herbage for his horse. Starting again at nightfall he reached the camp of Hasdrubal just as the light was showing itself in the east. The camp, it should be explained, was pitched outside the city. The larger half of the Carthaginian army occupied it. The remainder of the troops were stationed within the walls under the command of another Hasdrubal.

Cleanor, who had contrived to learn something about the arrangements of the camp, gave himself up into the hands of the officer commanding an outlying picket. Hasdrubal's letter proved, as he had anticipated, a sufficient passport, and he was conducted, after taking a few hours' rest, into the general's presence.

The personality of Hasdrubal was not by any means attractive, and Cleanor could not help comparing his puny physique and sinister expression with the commanding figure and noble countenance of Scipio. The Carthaginian may be best described by saying that he resembled the more ignoble type of Jew. It is often forgotten that the Phœnician race, of which the Carthaginian people was the principal offshoot, was closely akin to the Hebrew in blood and language. Hasdrubal showed the relationship plainly enough. His black, ringlety hair, prominent nose, thick, sensual lips, and keen but shifty eyes, were just such as might have been seen at that day in the meaner quarters of Jerusalem or Alexandria (then become the second capital of the Jews), and at the present time in the London Whitechapel or the Roman Ghetto.

On the present occasion, however, Hasdrubal wore his most pleasing expression. He was genuinely delighted to see Cleanor, as much delighted as he was astonished, for he had taken it for granted that the young man had perished in the destruction of Chelys.

"Hail, Cleanor!" he cried with a heartiness that was not in the least affected. "What good fortune has restored you to us? we had long given you up as dead."

Cleanor gave him in the fewest possible words a sketch of what had happened.

"And what can I do for you?" continued Hasdrubal. "If, as I hope, you are come to join us, I can find plenty of work for you. Things are looking more bright for Carthage than they have done for years past. We shall soon have all Africa with us. When that happens the Romans will have nothing left them but the ground that they stand on, and even that, I hope, not very long. You have heard of Bithyas with his squadron coming over to us? We shall soon have the rest of Gulussa's army following him, and then there will be Gulussa himself and his brothers. You have been in Mastanabal's household; tell me how he stands."

Cleanor produced in answer Hasdrubal's own letter. "The king's position," he went on, "is a very difficult one, and he must act with the greatest caution in your interests as well as in his own. If he declares himself too soon, his brothers will most certainly take the other side. What is wanted is a combination so strong as to compel all the three to declare themselves together. He wishes well to you; that I can say positively."

"That is good as far as it goes, though I should have liked something more definite."

"May I put before you," said Cleanor, "an idea which has been working for some time in my head? I am afraid that it is somewhat presumptuous in a youth such as I am to discuss such things; still, if you are willing to hear—"

"Say on, my young friend," cried the Carthaginian; "a son of your house is not likely to say anything but what is worth hearing."

"I spoke of a combination which would enable Mastanabal to declare himself. Don't you think such a combination might be made among all those who hate Rome or fear her? First there is my own nation. The League is, I have heard, little satisfied with its powerful friends, and it needs only a little blowing to set that fire a-blazing. Then there are the Macedonians, who haven't forgotten that they were masters of the world not so very long ago. There is Syria, there is Egypt, both of them afraid of being swallowed up before long. There are the Jews, kinsmen of your own, I believe. Is it not so?"

"Yes," said the Carthaginian, kinsmen, but not friends. I fear that we shall not get much help there."

"Then there is Spain. What do you know, sir, of Spain? Is there any chance of a rising?"

"The northern tribes still hold their own, but they will hardly go outside their own borders. They are quite content to be free themselves without thinking of others. Still, there is something that might be done in Spain. Only, unluckily, the Spaniards don't love us any more than they love the Romans. Perhaps they love us rather less. However, this is a promising scheme of yours, my young friend. Ah! If it had not been for you Greeks we should have had all the shores of the Sea long ago. We never could get you out of Sicily. It would be strange if you were now to make amends to us for all the mischief that you have done."

Cleanor, who had read history to some purpose, could not help thinking to himself that mankind would hardly have been better off than it was if Carthage had been mistress of the west. But he put away the thought. His lot was cast, and he could not, would not change it. The memory of the inexpiable wrong that he had suffered swept over his mind, and he set himself resolutely to carry out his purpose.

"And what do you suggest?" continued Hasdrubal.

"To go myself and see what can be done," replied the Greek.

"Good! And let no time be lost I don't mean that you are one to lose time; that you certainly are not; I mean that we had better not say anything about this to the authorities inside the walls. There will be questions, debates, delays, nothing settled, I feel sure, till it is too late. You must go unofficially, but I will give you letters of commendation which you will find useful. Succeed, and there is nothing that you may not ask, and get, from Carthage and from me. When shall you be ready to start?"

"To-day."

"And whither do you propose to go first?"

"First, of course, to Greece; then to Macedonia. I hear that there is someone there who calls himself the son of King Philip, and that the Macedonians are flocking to his standard."

"So be it. Farewell; and Hercules be with you!"

CLEANOR'S interview with Hasdrubal was followed by a long conversation with one of his staff, Gisco by name, in which were discussed the best and safest means of crossing from Africa to Greece. The Greek might have had at his command the best and fleetest war-galley in the docks of Carthage, but the idea did not at all commend itself to him. The harbour was not actually blockaded—Roman seamanship was hardly equal to maintaining a blockade, which often means the imminent peril of lying off a lee-shore—but it was pretty closely watched; the sea in the neighbourhood was patrolled by Roman ships, and the chances were at least equal that a Carthaginian galley would be challenged and brought to bay before it could reach Europe, and more than likely that if so challenged it would be captured. Some kind of disguise seemed to be far more promising of safety, and the more obscure the disguise the better the promise.

A little fleet of vessels was about to sail from one of the coast villages for the autumn tunny-fishing, and Cleanor resolved to embark on one of them. It had been one of his boyish delights to spend a few days from time to time at sea, and he had a long- standing acquaintance, which might almost have been called a friendship, with the veteran master of one of these craft. The tunny-fishing had always been too long an affair for the lad, who had his duties at home to attend to. The boats were about a month or more from home if the shoals had to be followed far, for the tunny is a fish that lives mostly in deep water. But there was a standing engagement that some day or other, when he happened to have leisure sufficient, the thing was to be done. Syphax—this was the old fisherman's name—knew nothing about his visitor except that he was a merry, companionable lad who had a sufficient command of gold pieces. To politics he paid no attention whatever. If there was war, it made no difference to him except, possibly, to increase the market for his tunnies, and raise the price. Romans and Carthaginians agreed in liking his wares; if they paid honestly for them, it did not matter to the fisherman what they did in other matters.

When, therefore, two or three days after his visit to Hasdrubal's camp, the Greek knocked at the door of Syphax's little house by the sea, he received a hearty welcome, and was asked no inconvenient questions.

"You're just in time, young sir," cried the old man, "if you are come for the tunnies. We start at sunset, and, if we have luck, we shall be among them by dawn to-morrow. Just now the shoals are pretty near, and we may catch a boat-load before the new moon—it is just full to-day. But you are not in a hurry, I hope, if we should have to go further afield."

"All right, Syphax!" replied Cleanor. "I shall be able to see it through this time."

The old man, who had, indeed, the experience of sixty years to draw from, was quite right in his prediction that they would find themselves among the tunnies at dawn. They had been able to get over a considerable distance during the night. At first their progress had been slow, for it was a dead calm, and the sweeps had to be used. About midnight, when they were well out of the shelter of the land, a light breeze from the south sprang up. The broad lateen sail was gladly hoisted, and the little craft sped gaily along, making, with the wind due aft, some six or seven miles an hour. Cleanor, who had fallen asleep shortly after midnight, not a little fatigued by the share which he had insisted on taking in the rowing, was awakened, after what seemed to him five minutes of slumber, by the captain.

"See," cried the old man, "there they are yonder. Thanks to Dagon, we have got among them quite as soon as I hoped."

And sure enough, about three hundred yards off, just in a line with the sun, which was beginning to lift a crimson disk out of the sea, the water seemed positively alive with fish, little and big. The tunnies had got among a shoal of sardines, and were busy with the chase. Every now and then some score of small fry would throw themselves wildly out of the water to escape their pursuer; behind them the water swirled with the rush of some monster fish, whose great black fin might be discerned, by a keen eye, just showing above the surface. Elsewhere, one of the tunnies would leap bodily into the air, his silvery side gleaming in the almost level rays of the rising sun. The sail had already been lowered, and the sweeps, after some dozen strokes to give a little way to the vessel in the right direction, had been shipped again. In another minute the little craft had quietly glided into the middle of the shoal.

Cleanor, in spite of all the grave preoccupation of his mind, was still young enough to enjoy the brisk scene which followed. There were two ways of securing the fish: the harpoon was one; the hand-line was the other, the hook being baited with a small fish or with a bit of brilliant red cloth. Syphax and two of his sailors used the former. Cleanor and the third sailor, a young man of about the same age, as being not sufficiently expert with the harpoon, were furnished with hand-lines.

The fun was fast and furious. At his very first shot the captain drove his harpoon into the side of a huge tunny. So strong was the creature that it positively towed the boat after it for a few minutes. This gave to Cleanor's baited hook exactly the motion that was wanted. It was soon seized with a force which jerked the line out of his hand, and would infallibly have carried it away altogether, had it not been wound round his leg, more, it must be confessed, by accident than by design.

A sharp struggle followed. For some time the fisherman seemed to get no nearer to securing his fish. It would suffer itself to be drawn up a few yards, and would then by a fierce rush recover and even increase its distance. But the line was of a thickness and strength which allowed any strain to be put upon it, and the hook was firmly fastened into the leathery substance of the fish's mouth. The creature's only chance of escape was that the tremendous jerks it gave might flatten the barb of the hook. This did not happen, for Syphax took good care that all his tackle should be of the very best quality, and, after a conflict of half an hour, Cleanor had the satisfaction of seeing his prey turn helpless and exhausted on to its side. He drew it up close to the vessel, glad enough to give a little rest to his fingers, which were actually bleeding with the friction of the line. A sailor put his fingers into the animal's gills, and lifted it by a great effort over the gunwale. It weighed a little more than a hundred pounds.

The sport continued till noon, only interrupted by a few short intervals when the shoal moved away and had to be followed. By noon so many fish had been secured that it became necessary to take measures for preserving them. They were split open and cleaned. The choicest portions were immersed in casks which held a liquid used for pickling; other parts were salted lightly or thoroughly, according as they were intended for speedy consumption or otherwise.

"You have brought us good luck," said Syphax to his guest, as they shared the last meal after a day's hard work. "In all my experience—and it goes back sixty years at least—I don't remember getting so much sport so soon. Another day or two of this and we shall have a full cargo, and may go home again."

He had hardly spoken when his eye was caught by a strange appearance in the water,—strange, that is, to Cleanor, but only too familiar and intelligible to the old man.

"Ah!" he cried, "I thought that it was too good to last. Do you see that eddy yonder? And look, there is the brute's back- fin."

"What is it?" asked Cleanor.

"A shark, of course," replied the old man. "They never bode any good to anyone. Dagon only knows where we shall find the tunnies again. They will be leagues away from here by sunrise to- morrow, and there is not telling what way they will go. However, we have done pretty well, even if we don't see them again this moon. To-night we will lie-to; it will be time enough in the morning to decide what is to be done."

Cleanor had begun to fear that his experiment might turn out to be a failure. Nothing, he knew, would induce the old man to sail another league away from home when once his cargo had been completed. Accordingly he had hailed the shark's appearance with delight as soon as he comprehended what it meant, and now he turned to sleep with a lighter heart.

Again did the old fisherman show himself a true prophet. The next morning, and for many mornings afterwards, not a tunny was to be seen. The weather, however, continued fine, and the little craft made its way in a leisurely fashion towards the north-east, a sharp look-out being kept by day, and, as far as was possible, by night, for the object of pursuit. Two days had passed in this way when masses of floating sea-weed and flocks of gulls began to warn the captain that he was drawing near the land.

"We have been on the wrong tack," he said to Cleanor, "and must put her head about. We are more likely to find the fish in deep water than here."

"Where are we, then?" asked the Greek.

"Almost within sight of Lilybaeum, as far as I can guess."

Cleanor felt that it was time to act. "Will you do me a favour?" he said.

"Certainly," replied the old man, "if I possibly can."

"Well, then, put me ashore."

"That is easy enough, if I am not wrong in my guess as to our whereabouts. How long do you want to stay? I should not like to lose this fine weather. As for landing, I should have had to do that in any case, for we are getting short of water."

"I don't want you to wait for me. Only land me and leave me."

"What! Tired of the business, I suppose. Well, we have been a long time doing nothing, but we must come across the tunnies soon."

Cleanor, who was anxious above all things not to be thought to have any serious object in view, allowed that the time did seem a little long. He had friends and kinsfolk, too, in Sicily, he said, and it would be a pity to lose the opportunity of paying them a visit. It was arranged, accordingly, that he should be landed, and that the crew should replenish their water-casks at the same time. He parted with his friends on the best of terms. Two gold pieces to the captain and one to each of the crew sent them away in great glee, singing his praises as the most open- handed young sportsman that they had ever had to do with.

It is needless to relate in detail our hero's journey through Sicily. He bought a stout young horse, one of the famous breed of Sicilian cobs, at Agrigentum, near which place he had been landed, and reached Syracuse without further adventure. At Syracuse he found a merchant vessel about to start for Corinth, secured a berth in her, and reached that city after a rapid and prosperous voyage.

MOST of Cleanor's fellow-passengers on board the Nereid—for this was the name of the singularly un-nymphlike trading vessel that carried him to Corinth—were a curious medley of races and occupations. Corinth was the mart of the western world, and was frequented, for business or for pleasure, by all its races. There were soothsayers from Egypt, who found their customers all the more credulous because they boasted that they believed in nothing; Syrian conjurors; Hebrew slave-dealers; a mixed troop of commercial travellers; and a couple of grave- looking, long-bearded men who, in spite of their philosophers' cloaks, were perhaps the greediest, the most venal of all.

One passenger, however, was of a very different class. He was a Syracusan noble, erect and vigorous notwithstanding his seventy years, whose dignified bearing and refined features spoke plainly enough of high breeding and culture. He was a descendant of Archias, the Corinthian emigrant, who, some six centuries before, had founded the colony of Syracuse, and he was coming, as he told Cleanor, in whom he had discovered a congenial companion, on a religious mission. The tie that bound a Greek colony to the mother city had a certain sanctity about it. Sentiment there was, and the bond of mutual advantage; but there was more, a feeling of filial reverence and duty, which was expressed by appropriate solemnities.

"I am bringing," said Archias—he bore the same name as his far-away ancestor—"the yearly offering from Syracuse the daughter to Corinth the mother. I have done it now more than thirty times. But I feel a certain foreboding that I shall not come on the same errand again. If that means only that my own time is near, it is nothing. I have had my share of life. The gods have dealt bountifully with me, and if they call me I shall go without grumbling. But I can't help feeling that it is something more than the trifle of my own life that is concerned, that some evil is impending either over Syracuse or over Corinth. As for my own city, I don't see where the trouble is to come from. We have long since bowed our necks to the yoke, and we bear it without wincing. For bearable it is, though it is heavy. But for Corinth I own that I have many fears. She is restless, she is vain; she has ambitions to which she is not equal. The gods help her and save her, or take me away before my eyes see her ruin!"

As they were drawing near their journey's end Archias warmly invited his young friend to make his home with him during his stay in Corinth.

"I have an apartment," he said, "reserved for me in the home of the guest-friend of Syracuse. The city rents it for me, and makes me an allowance for the expenses of my journey. I feel bound to accept it, though, without at all wishing to boast of my wealth, I may say that I don't need it. You must not think that you are burdening a poor man—that is all. I can introduce you to everybody that is worth knowing in Corinth, and, if you have any business on hand, shall doubtless be able to help you. And it will be a pleasure, I assure you, to have a companion who is not wearied with an old man's complaints of the new times."

Cleanor thankfully accepted the invitation. When the Nereid reached the port of Corinth he found that the Syracusan's arrival had been expected. A chariot was in waiting at the quay to convey them to the city. At the apartment all preparations for the comfort of the guests were complete—it was a standing order that a provision sufficient for two should be made. First there was the bath,—more than usually welcome after the somewhat squalid conditions of life on board the merchantman,—and after the bath a meal, excellently cooked and elegantly served.

The meal ended, Cleanor felt moved to become more confidential with his new friend than he had hitherto been. Naturally he had been very reserved, giving no reason for Archias to suppose that he had other objects in his travels than amusement or instruction. But he felt that it would be somewhat ungracious to maintain this attitude while he was enjoying so kind and generous an hospitality. In a conversation that was prolonged far into the night he opened up his mind with considerable freedom. His precise schemes he did not mention; they were scarcely his own secret; and he said nothing about Hasdrubal, feeling—for he had studied history with intelligence and sympathy—that a Syracusan noble would scarcely look with favour on anything that came from Carthage, the oldest and bitterest enemy of his country. But he gave a general description of his hope and aim, a common union of the world under the leadership of the Greek race against the domination with which Rome was threatening it.

The Syracusan listened with profound attention. "It has done me good," he said, "to hear you. I did not know that such enthusiasm was to be found nowadays. The very word has gone out of fashion, I may say fallen into disrepute. It used to mean inspiration, now it means madness. Our young men care for nothing but sport, and even their sport has to be done for them by others. They have chariots, but they hire men to drive them; the cestus and the wrestling ring are left to professional athletes. The only game which they are not too languid to practise with their own hands is the kottabos, and the kottabos is not exactly that for which our fathers valued all these things, a preparation for war. I hate to discourage you, but I should be sorry to see you ruining your life in some hopeless cause."