RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

Argosy, 25 May 1935, with "Sorcerer's Treasure"

He played a grim game of murder—in a country where

there was

little chance of vengeance of the law—for a stake beyond

price.

ROCKY GHEE might have beaten me to death that time, for he was drunk. Tied to the whipping post back of the sawmill, I had fainted under blows of the blacksnakc.

It was by no means my first beating, but it was my last at the hands of Rocky Ghee. I was fourteen years old, big for my age, bound out (or as they say in Alabama, "bonded") to work at a wage of $5 for Rocky, all the months until I turned twenty-one. He never paid me one cent.

There were no reasons for the beatings, outside of the fact that about once a week Rocky got drunk on shinny. And, of course, I tore into him desperately and fruitlessly every time he hauled out the blacksnake, trying to annihilate him with my fists before he could get Negroes to tie me.

This time I awoke prone on the ground. A girl I knew of (rather than knew) named Marjorie Grandeman, was bathing the deep, bloody welts on my back, and weeping softly.

"He'll never do that again! Poor boy!" she kept saying over and over. "When you feel better, read this. He sent it!"

There was a different accent on the last pronoun. Instinctively I guessed the person she meant, and tiny chills came down my arms. There was, not far away in the heart of the piney-woods, an awesome personage whom the blacks and Cajans spoke of in whispers. He was a sorcier, a worker of magic. More than that, he was supposed to right all wrongs. All you had to do was send him a pig or a chicken, dressed for table.

Your troubles would vanish, and your enemies bite the dust—only, I had never owned a pig or chicken I could have sent.

The girl left me hurriedly as I sat up, staring glassily at the crumpled letter. It was addressed to Rocky Ghee. Evidently he had read it, stopped the beating, crumpled it up and dropped it there as he went for more drink. It warned:

Quit beating that boy, or I shall send a horror in the night to seize you and bring you to judgment!

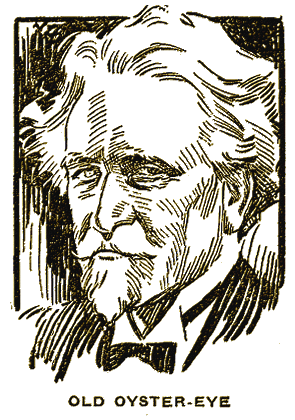

Old Oyster-Eye.

Just how even the brutal lumbermen felt about crossing that

unknown sorcerer, who was said to dwell in a cave of skulls in

the north hills, can be seen by the fact that even Rocky Ghee was

shaken. Though eight months more elapsed before I got hold of a

little money, and made my escape from the camp, he never touched

that blacksnake to my back again.

It did not alter my feelings toward him. Sometime I was going to kill him with my hands. I did not guess that already a horror had come more than once in the night, beckoning to him with grisly finger, and that I was to be cheated of the vengeance for which I would work and plan for several years.

JUST a word about myself. Before I was born, my father, Charles Lamont, deserted my mother. My mother died when I was a month old, with only three or four hundred dollars in her possession. I spent from then until I was twelve, at an orphanage school. Then the law said I had to be bound out, until I reached my majority.

My mother had been a great beauty, a Cajan girl educated in France. For years I kept her picture, until it yellowed and faded out completely. Why or how my father could have deserted her, I could not guess.

When I got away, and finally reached Chicago, I got a job at $6 a week doing odd jobs around Hayworth's Gym. This year and two more like it are not important, except I went to night school down on Clark Street, and put on the gloves with somebody, every day at the gym. Pug Hayworth got so he'd match me for a couple of rounds with some of his business men amateurs, who weren't so hot. I went under the name of Carter, up there.

Then one day he came to me and said, "Kid, that lousy so-and-such, Brackett, has stood me up on a prelim down to East Chi, t'night. Wanta take a four round lickin' for twenty-five an' carfare?"

Naturally I cut school that night, and went. Pug was surprised when I got an easy kayo in the second. So was I, but did I eat it up! I meant to be a fighter who could kill a man with his fists, before I went back to Alabama!

FROM that time on I was a ham-and-beaner, though I kept my gym

job two years more. The scraps helped. I was broadening through

the shoulders. Then, two years later I put on the tape and gloves

in the Milwaukee Auditorium in a semi-final. Johnny Dundee and

Willie Jackson, lightweights, were fighting, the final, but I

never saw that bout. A 230-pound punk named Sailor Grundy, a

Limey, had put me asleep for two hours. I didn't feel too bad

about it afterward, for I was just shading 180, those days. I did

do a lot more studying for a while, though.

Boxing right then was under the kibosh in Chicago. So I got some matches out in Saeger's Arena, in Aurora.

Good practice, but there wasn't much money in it for a heavyweight. Pal Moore of Memphis, Frankie Schaeffer and his kid brother, and the new flash, Sammy Mandell, were fighting there at Saeger's, and turning all the fans' interest toward lightweights. Sammy became world's champion a little later. But I got along without a manager now, and saved every nickel I could get. The month I was twenty-three I had four thousand in the bank, a junior college diploma from LeAvis Institute, and a sore ear which wanted to cauliflower. I declared myself a vacation, and went down to Alabama to kill a man. The four grand, I figured (having seen how it worked around Cicero, Burnham and Chicago) would be about right to pay a lawyer to get me free afterward.

You know how the woods grip you, after you've been away? I took some long breaths, and felt myself grow, when I started out to find Rocky Ghee, the man I wanted to kill.

Rocky had died of too much green shinny, nearly three years before. My carefully planned vengeance was a fizzle.

Just chance kept me from going back north, and taking some more shellackings in semi-final bouts. I met an invalid named Shapley, who had a five-acre citrus and pecan orchard in the pine hills north of Citronelle. The Choctaws, Cherokees and Creeks used to send all their sick braves to this exact spot; but history does not tell how many, of them, recovered.

The place was doing Shapley no good at all. He offered me his excellent cypress cabin and five-acre place at a give-away price. I bought it and he went to Arizona. I hope he recovered, though I never heard a word from him.

I had no taxes to pay. This sounds funny, but it was true. My new holding was north of the Mobile County line, in Washington County. To an Alabaman that tells the story; Washington County in that year did not even have a sheriff, and of course no tax-collecting organization. It had practically no population of white skin. Chatom was the so-called county seat and biggest metropolitan center. Chatom had a population of less than 200, even if you counted all the pickaninnies carefully. Most of the people of the woods were Cajans, who held their squatter cabins under shotgun title, and did not live in towns to any extent.

The Cajans were and are Choctaw Indian and Acadian French, the people of Evangeline. They are intolerant of whites and negroes alike, suspicious of both.

Therefore, as became extremely important, law in Washington County was fully as primitive as anywhere on the North American continent.

GHOSTS and women never, had meant a thing in my life. There

was only that one queer experience with a sorcerer, who probably

had saved me from being beaten to death. Why he had done it I had

failed to guess.

Now ghosts and women—and spectral treasure—were to step right in and take charge of me!

Of course I had no suspicions of that. I was feeling up-stage and important, with my little five-acre orchard. I had made one trip down to Citronelle in the ancient Ford I got from the invalid Shapley. Then I had spent seven luxurious days as a landed proprietor, working as much as I wanted in the trim orchard, all surrounded by stout, nearly new "hog-tight" fencing, against the razorbacks and piney-woods cattle which range free all winter long.

Everything was in excellent shape, due to the care of the big buck Negro, Lonnie. Lonnie was as tall as myself, and outweighed me thirty pounds. He was a magnificent specimen, carved out of solid night and with face and naked torso seemingly oiled with liquid lightning. What a fighter he would have made!

I kept Lonnie for the cultivating; and I promised myself that I'd try to teach him enough ring science so I could have an occasional friendly bout. I set him to work scrubbing the four room interior of the cypress cabin with antiseptic soap. Until it was thoroughly cleaned and aired, I slept in an old Army tent I brought from Mobile.

Twice when Lonnie went down to bring up buckets of water from the river, I noticed that he crouched a little, and stared upstream quite as though he feared something might leap at him from that direction. I asked him a little sharply what was wrong, but Lonnie shook his head and said nothing. He never was one to talk.

I recalled from boyhood days the story of that big, undergrown jungle of a place, known then as the Grandeman estate. There was a big wooden mansion of a house, set amid terraces, artificial ponds, and groves of gray bearded live oaks from which the Cajans cut the spheres of mistletoe to sell at Christmas.

I vaguely remembered that this woods retreat had been built by a wealthy white man who had been in some sort of trouble with the law up north. He had lived in the place only a year or two, and then had committed suicide by slashing his throat with a razor. Since then no one had dwelt there. Even Cajans avoided it; and the blacks would not go near what they called the Cunjah House, even in daylight.

The thought stayed with me, and next day it seemed to be a good idea just to take a ramble over the old place. With an unloaded shotgun under my arm and few shells in my hunting jacket, I went out to the fence, just a little way beyond the spot where Lonnie was working, banking up hills of compost around the roots of cumquats rather recently grafted on the tough and thorny trifoliata. I had a sulphur candle burning in the cabin that day, and neither Lonnie nor I would enter till next morning.

I had set my gun carefully through the fence, and was just about to vault over, when I heard rapid footsteps behind. Then big Lonnie came up, clutching at my arm.

"No, Boss! No, Boss!" he pleaded in that deep, mournful voice he used so seldom. "Don't go Gateway!"

"Why the hell not?" I grinned. "Ghosts all run away from me. These marks were all made by men!" I touched my rather flattened nose and cauliflowered left ear.

BUT Lonnie was not joking, and it was not ghosts he feared at

this moment. I had a hard time getting out of him what he did

mean. And then I got a sort of eerie thrill, my own self.

"Ah tell yo', Boss," he finally blurted out with sepulchral frankness, "Ol' Oystah-Eye done lib da'."

"The devil!" I said, astonished.

"Yessah, Ah specks he is!" croaked Lonnie, and trudged slowly back to his work, casting one backward glance over his glistening shoulder to make certain I was not venturing across the fence.

I did not venture. This surely was something for thought! Here, living right next me, if Lonnie was correct, was that queer individual who had saved my life!

I must confess that I did not feel any particular gratitude toward him. In the days after that last beating, I had found out all the mill-men knew about him. They pictured him as a monster, a wrinkled, ugly old devil with one white eye and one black eye. Usually he looked at you with the black one. When the white eye turned toward any miserable, shivering wretch, that unfortunate fell down frothing in conniptions, and died.

They had told me his Cajan name, too, but right now I could not bring it back to mind. La—Laverne? No, that was not quite right. But no matter. I'd remember sometime.

ACCORDING to rumor, Old Oyster-Eye had dwelt in a strange cave filled with skulls of the men he had bewitched. He had been accused of making figures out of red clay, and endowing them with life for a single night. He was served by black zombies, dead men he had resurrected for his foul purposes.

Just superstitious rot, of course. But it certainly was true that he possessed power, and that sometimes, at least, he exercised that power to prevent injustices.

Certainly this famed magician had not lived at the Grandeman place in my youth. I got a kick out of the thought of having him for a neighbor; but even at that I hesitated to wander over casually and make his acquaintance. Since he was Cajan, his greeting to one whom he thought a damn-Yank trespasser might well be a charge of chrome-nickeled buckshot.

In the work to be done I shelved Old Oyster-Eye for future consideration, little knowing how suddenly my everyday affairs were to be interrupted unpleasantly by him. On the following Saturday, with a list of provisions and hardware as long as a hog's hind leg, I sent Lonnie along to his woods cabin with a week's pay, and drove down the fifteen miles to Citronelle.

The first six miles were hard driving, through a maze of narrow and obstructed wood roads leading this way and that through heavy blackjack and gum forest. Shapley's old Ford climbed over fallen trees, scraped between stumps, and managed to make it. On the way I blazed about eighty trees, since I was not at all certain of being able to find my way home after nightfall.

The last nine miles were easier. The road was little more than a pair of oxcart ruts, but it was marked with the white, gold and white triple band of the M.V. Highway. A Ford could buck through, although a big machine would go hub deep in sand almost anywhere.

SOON after supper, with my jalopy loaded, I started back north

to Washington County. Nothing happened until I was off the

highway, following the tree blazes I had made, and thankful for

them.

Then I swerved around a tree, cutting the wheel short—and a gasp burst from my lips. Right ahead, part way up a dark tree bole, someone was glaring a flashlight straight into my eyes!

In a second I laughed mirthlessly, and drove ahead. It was nothing but a bobcat. The beast's eyes had caught the flare of the Ford's headlights, and feline eye-reflectors had flung it back into my face.

Just the same, I got thinking about eyes—one white eye that rarely turned to regard a person—and little prickly chills like quick-melting snowflakes began to play across my shoulders. After dark I felt just as happy not to be meeting the Cajan sorcerer anywhere in the woods. But I was to meet him that night.

Just about half a mile from my fenced five acres, where the ground began to slant downward into the deep ravine of Dog River, I saw something across the road. Another fifty yards and I reached it, stopping the car and frowning at the obstruction.

It was a fence, new, and not of the hog-tight construction needed for any plantation or orchard because of the Alabama herd law! This was a tight strung barrier of four barbed wires and brown, freshly peeled cedar posts. There was an iron-pipe gate, also wire-strung, the width of a car; but it was chained and padlocked now.

I began to get angry. This was the road to my home, the nearest and best one. What right had anyone to fence across it? Whoever owned that padlock was going to find it broken in the morning! I went into a side pocket of the puddle-jumper, after a small ball hammer I carried there.

I was getting angrier. That fence had not been there when I drove down to Citronelle this forenoon! Anyhow, what good was a barbed wire fence here? It would keep out cows, but not the all-destructive razorbacks which are so bold and savage they will walk right in any open door and chew up chairs and tables if they find nothing more succulent.

I lifted the hammer, aiming at the big Yale padlock I placed with its chain on top of a length of gate pipe. My arm froze at the top of the stroke. Four dark forms had risen to their feet close to me!

Four big Negroes. They wore chambray shirts and ragged overalls; barefoot, of course. They had no guns that I could see. And they said nothing, which was unnatural and ominous. Just waited—for me to whang that Yale lock and unchain the gate!

The fence was between us, and I let it remain so for the moment. The realization had come suddenly that this was the old Grandeman estate, the edge of it, and these blacks were without doubt the servants of that weird person, Old Oyster-Eye!

THEY were flesh and blood, of course, not the zombies of

superstitious rumor, and I did not fear any or ail—as long

as they did not produce guns. Still I hesitated. I wanted to know

more about this before I started the doubtful enterprise of

mopping up on four muscular men, no matter how untutored. In the

direct glare of headlights from the still running Ford, I

probably could hand around kayos easily enough; but if one of the

four wanted to steal around into the shadows and tackle me from

behind, I wouldn't have a chance.

So I held to my temper. "Why is this fence here?" I demanded sternly. "I have to use this road to get home." This was not absolutely so; another, more roundabout road existed, but I had no intention of trying to find it this night or any other time.

The four colored men stood silent, waiting. I did not like that one bit, and repeated my question more sharply, at the same time dropping my right hand to the holstered Colt pistol at my thigh. A wise man never goes unarmed in the woods at night. Or in daytime either, unless he is right in his own dooryard.

Only one of the four blacks showed uneasiness. This one, on the left end of the line, shifted his feet and coughed apologetically. I concentrated on him, demanding an explanation. Finally he looked furtively over his shoulder, and said huskily:

"Ohdahs of de boss, sah! Nobuddy comes in thisaway!"

"And what are you going to do when I smash this lock and drive through?"

"Th'ow yo' all an' de cab in de swamp!" came the husky but determined reply. It decided me. I raised the hammer again, I had been tolerant, but this was just too much.

Crash! The lock broke, the chain came away. I swung wide the gate. The blacks just stood there—waiting!

Then I saw two new figures. At least I thought I saw two, and I was right, though only one came directly from the shadows of the brush, up to the gate. I caught one glimpse in the light of the lamps, as the Negroes melted out of his path. And I turned back in the gateway to face the man a thrill all down my spine told me must be the piney-woods sorcerer, Old Oyster-Eye!

Heaven only knows what I expected to see. Probably a greasy, long-haired, buck-toothed ruffian with an evil leer, and a cataract over one eye. Cunning, even sinister cunning, is not lacking in Cajans; and I had put down this creature as one who surpassed his fellows in chicanery and the implanting of fear. I know I was ready at once to despise and to fear some dirty trick he might play upon me if I crossed him.

I give my word I was completely punch drunk from what I did see. Walking quietly with poise, a bareheaded man with a glorious mane of snow white hair, a white mustache and a triangle of chin beard of the sort known as Van Dyke, came straight toward me at the fence. Pie was wearing a dinner coat and black tie, probably the only specimens of this costume to be found nearer than the city of Mobile!

He was not more than five feet ten in height, but carried himself as erect as a West Point martinet. And I saw a thin, long nose, chalk white skin quite unlike the golden tan which is Cajan, and two eyes like none others T have ever seen.

One was jet black, a sparking onyx jewel beneath its bushing snow-white brow. The other diverged a little, not much. It was not a blind eye at all, just a freak in color. That night I thought it white, with the pupil indistinguishable and the iris light gray; but that was the effect of the headlights. In truth the whole eye showed a curious purplish gray in sunlight, with one black dot in the center. That was the pupil.

"I UNDERSTAND that you have the cabin next to this land, Mr.

Shapley," said a deep, resonant voice which seemed to come from

far down under his spotless shirt front. "And I must apologize

for this treatment. You are a sick man? You do not look it.'

"However," he went on, before I could find words to correct his impression, "I have taken over this place next to yours. And since I desire no company—not any!"—those words suddenly crackled—"I have fenced the land. After tonight, you cannot come through here. I believe you have another road. Tonight—"

"Pardon," I said caustically, finding my voice. "I do not know your name, but mine is not Shapley. I bought him out, and am living in his cabin. Did you purchase the old Grandeman place?"

"My name does not matter," he said stiffly. Somehow the news that I was not the invalid Shapley appeared to make a big difference in his attitude. "And I am living at Grandeman's—no matter under what circumstances. I forbid trespassers, and am in a position to enforce my commands!"

"Then I'm to understand you won't let me through—now, at night, when I have to go ten miles around, and probably get lost?" I demanded hotly.

"Exactly! I know why you have taken the Shapley place, young man. You and the rest may as well go back to Atlanta and New Orleans or wherever you came from. I am warned!"

And with that the old fellow flipped a hand under the shiny lapel of his jacket, and came up with a shiny short-barreled revolver!

He, likewise took two measured strides forward, his black eyes burning into mine. I turned sidewise to scrutinize him, not a little puzzled and thrilled. Old Oyster-Eye had gained in stature, as far as I was concerned; and oddly enough I was not in the least inclined to take his threat at less than face value.

He meant it. What the stuff about Atlanta and New Orleans could signify, was far beyond me; 'but there was no doubt at all that if I insisted upon getting home by this short road, I was going to have a fight to the death.

And perhaps I did not even have right wholly on my side!

In mid-stride the old man stopped. He even blinked and made a queer, gasping sound. Then the shiny revolver slowly came up to breast height, leveled, aiming at my heart!

"Your name?" cried Old Oyster-Eye with electrifying tenseness.

"Your name?" demanded Oyster-Eye.

"Why—James Carter!" I replied, almost stammering.

"You lie! Damn you, you lie!" Now the deep voice was quavering with inexplicable rage. "Get out of my sight before I have these men tear you to pieces! Get out!"

He flung up his right arm, and probably from the convulsive anger which consumed him in that maniacal moment, he pulled trigger. A. spurt of fire angled upward into the trees. The darkies gasped and groaned in unison. All four of them crept forward, crouching, and I saw them. What on earth did it mean? They were coming like four black apes, ready to rend me where I stood!

I was shaken. Perhaps this old sorcier was mad. I did not wait to analyze. In that moment I honestly think I should have struggled like any untutored savage, if the blacks had set upon me. I had been scraped clear down to the roots. The matter of a road to my place no longer seemed important.

I turned the Ford. I was stepping on the gas, anxious to get away and think over all I had heard and seen. But the white-maned sorcerer came up to the running board. He leaned in, and his black eye glowed red like a rabbit's—but unlike a rabbit's in every other way!

"You name is—Lamont! Or—should—be!" he grated. "I should slay you out of hand, but I shall not!"

The last words were spoken in French, which I understood.

"Yes, it is—Pierre Lamont!" I whispered. "How do you know?"

"Go. Or die," he said, slowly raising the revolver. "Oh, damn you to hell, go!" I went.

THE homeward trip was irritating and tiresome. I had to go back six miles to the highway, north then to Tiger on the railway, pick up a Cajan guide, then thread a way among the faint, aimless wood roads which seem to persist a long time after the reason for their being has vanished.

So by the time I paid off the Cajan, and got out to lower a section of my own tight fence for passage of the Ford, I was half blind from lack of sleep, and savage at what I now considered my mistreatment.

The queer, magnetic hold which that white bearded oldster had exercised upon me had vanished. Even the fact that he recognized me as Pierre Lamont did not seem strange any longer. After all, he had been a power in the woods at the time I was a bond boy slave; and it might be that my appearance had not changed as greatly as I imagined. Or—and here my jaw set broodingly—Old Oyster-Eye might have known my father. If so I meant to wrest the secret from him somehow.

If I ever met the man who had been my father, who had left my mother to die in a charity hospital, and his son to be reared a Cajan orphan and bond servant to bullies of the lumber camps, that man would have to talk fast and suavely to me. Or a reckoning would descend upon him.

Knowing the dark thoughts which held me were largely the result of being thoroughly tired and dirty from the long, hard day, I climbed stiffly out of the car, undressed in the cabin, and went down for a dip in Dog River. The water felt far too cold, but I clamped my jaws and lathered. Then one final plunge and furious swim the length of the hole and back, and I waded out to towel myself and get ready for a few hours of slumber.

The towel around my waist, I turned to go up to the cabin. Suddenly there came a screech of agony or superhuman terror, throttled into horrid choking sounds which presently ceased! Unarmed, naked except for the rough towel, I crouched and stared upstream—toward Grandeman's—into the inky blackness of the further bank.

Then over my whole body crept shivery chill which had no reference to the temperature of the night. Over there, quite a way up the bank, a whitish, half luminous figure appeared! Another—in all, four of them! They came out of the brush silently in single file; and somehow, either because of the robes they wore, which were white and seemed to exude phosphorescent light, or because my eyes had become accustomed to the obscurity, I could see them as tall, faceless entities in robes, hooded and bent a little forward as they walked.

They only appeared, and almost instantly disappeared into a tunnel of underbrush; but in that long five seconds I had seen that two of them carried something limp and horizontal—a human body! That was only a guess, but I was sure of it.

Silence. I waited a full five minutes, wondering just what I had seen happen. These figures looked a bit like those of the robed and hooded Ku Klux Klan, whom I had seen once on parade in Citronelle. They had been powerful in my boyhood, and even now were known to exist and have their secret meetings.

Certainly Old Oyster-Eye, a Cajan, was not a member. Could the Klan have come after him, and was this one of their weird captures I just had witnessed?

Thoughtful, but of no mind to interfere, I returned to the cabin, dressed fully except for my boots, and lay down on my cot bed. Within a space of minutes, despite every throbbing question in my brain, I fell into deep sleep.

When Lonnie woke me I smelled coffee, and the early sun was sending light yellow rays through the window on a slant. Sometimes Lonnie did come early enough on Sunday to get breakfast; that meant usually that his Saturday night crap game had resulted disastrously.

BUT I was to learn that hunger was not what brought him this Sunday, morning. As a kaleidoscope of yesterday's strange events flashed through my still sleepy mind, I noted that Lonnie's complexion was purple—which was as near to turning pale with worry and fright as one of his color skin could come. His eyes showed whites all around the irises, and his deep, melancholy voice was oddly thickened.

"Boss!" he said urgently, seeing me trying to wake. "Dey's a one heah fo' to see yo'! One furn dat place!"

He did not need to specify. With an exclamation I leaped up, wondering if I was being waited on by the white-maned sorcerer.

"Where is he?" I asked, hastily splashing water into a basin, and washing my face.

It proved that my visitor was feminine, though Lonnie did not enlighten me. He merely pointed off to westward beyond the trodden, grassless door-yard. There was a six-foot clump of pink-belled mountain laurel, but no sign of a visitor. I looked doubtfully at it; but somehow the morning sun chased the fears of night, and I strode forward, beginning to frown. I wanted to know several things, and Old Oyster-Eye had better begin to enlighten me right about now.

"Mr. Lamont!"

The truculence whished out of me like burning powder out of a Christmas firecracker squib. I stared, halting involuntarily. The girl who had been seated there on a fallen log got up and looked seriously at me.

A girl! She was clad in lace boots, breeches and open-neck shirt of new khaki, and she looked almost overweighted with the fluffy red-brown mass of marcelled hair above her small, oval face. At first glance I knew who she was, and that is why I could see her clearly enough to describe.

HER name was Marjorie Grandeman; and she had dark blue eyes, strange eyebrows that seemed only as wide as a horsehair (plucking them was a new outrage at that time), and a rather wide mouth carefully reddened until it seemed to be bleeding. Her nose was uptilted and irregular. I thought she looked shocking, in spite of the wistful, grave air of greeting.

I was to get used to the cosmetics in time, though.

"Yes, Miss Grandeman?" I answered, conscious of a funny warm feeling in my cheeks. She looked at me, startled, and I hastened to add: "I used to live near here, and I remember you when you lived down in Citronelle."

"Oh, I see. I—don't remember you. But ho matter," she went on. "I came to tell you I—I was there at the gate, last night. Grandfather is furious. He—I'm afraid he may do something to you. I felt I had to come and ask if—well, if you couldn't go away somewhere."

Something in my face must have showed her how foolish was any idea that I would leave this place which I had just bought, and run away, merely because Old Oyster-Eye had become my neighbor. The fact that Marjorie Grandeman called him her grandfather, and that she was either daughter or granddaughter of the man who had built this mansion in the woods, and then committed suicide, complicated matters for me. It also seemed to show that Old Oyster-Eye was in possession of the place rightfully enough.

His name, I dimly recalled now, was Lavoisier. He might have had a daughter married to the northerner, Grandeman. Probably that was it.

Miss Grandeman shook her head. "I didn't think you would do that," she admitted, before I could speak. "But there is a war on, you know. Or don't you?" The thin brown lines of eyebrows arched in question.

"There's going to be," I said wryly, "unless I can get right of way through on that road! But you meant something else, of course. No, I had no idea that anyone at all lived at Grandeman's now, or that the estate still was in the family. When I saw you, years ago—" I stopped, almost biting my tongue. I had remembered more about this girl. She had been left penniless, and had been taking care of three children for some people named Bayliss, although little more than a child herself.

"You were right enough," she admitted quietly. "Granddad does not own the old place. He says shotgun title is the way of the woods. I—I can't cross him any way, now he seems to be in awful trouble, particularly. You see, I owe him my education—everything!"

QUIETLY and with a straightforward frankness at variance with

her oddly artificial make-up of face, she told me in a few words

how she happened to be living here. Going straight from a

finishing school, and from summers spent with her father at

racing capitals of the world and gambling resorts like Cannes and

Monte Carlo, into the drudgery of housework and the care of three

children of a poverty-stricken piney-woods white family, had been

too much for her health.

After a year she had been pale,'sick, emaciated and out of even that meager means of keeping soul and body together.

Then It was that Lavoisier came, quietly offered the assistance those of her own race had withheld; and she had been overjoyed to accept.

Good clothes, money, a respectable widow to act as chaperon in the city, a year of preparatory school, then Tulane University. And this summer was the first time she had revisited the woods. She had graduated, and meant to try for a stenographic job in the city; but old Lavoisier had not cared for that. He asked her to come to the woods for this one summer, after which he thought he might go to live abroad, and take her with him. She had not been able to refuse, although she had come quite believing that he was relatively poor; that he had strained all his resources to give her the education and comforts she had enjoyed.

Her surprise was not unmixed with horror to find that she came back to a house of queer, somber luxury—and the very house in which her own father had committed suicide!

"I don't know why he came to the old place!" she finished in a hushed, earnest voice. "I have only Mrs. Col-man with me—the lady I lived with in New Orleans. And we're afraid to breathe most of the time! He has a number of blacks who work for him at something, and never speak! I have begged him to let me go back and work in the city, but he just shakes his head. He's kind to me—too kind. I—well, I—think there's something wrong. Something besides the fact that he's afraid; that there have been men trying-to get at him and us, in the house!

"There was a regular fusillade of bullets came through the downstairs windows one night, smashing them and wrecking things in the rooms. A machine gun, I think!"

"For heaven's sake!" I said, impressed. "You're sure it just wasn't one of those black men—guards—he has, letting go a Tommygun by mistake?"

She shook her head, smiling wryly. "Positive!" she said simply. "You see, there are no firearms on the whole place. He won't have them."

"But I saw his pistol, and he let go a shot!" I objected.

"Oh, that. Just blanks. He won't have lead-loaded guns of any sort on the premises. He keeps that revolver loaded with blanks, in his own possession. It's just for signalling—or for scaring away a rattler that happens to get in the path.

"No, Mr. Lamont, grandfather—I call him that—has other means of protection. I don't know what they are, exactly. I—I'd rather not know!" She shivered slightly.

"MR. LAVOISIER had a reputation as a worker in black magic

long before you knew him," I said dryly. "I fully expected to

find him in feathers, skins, ochre paint and clacking a pair of

human shinbones for castanets, like an old Choctaw mingo.

The dinner coat had me on the ropes."

"I wish—well, I don't suppose you'd consider going away for just a while?" she asked, moving to go back to the fence. "No, I suppose men are that way. I have to get back. He'll be looking for me, or Mrs. Colman will. The house was queer and quiet this morning—breakfast all ready for me, with hot coffee on the stove, but not a soul around. Mrs. Colman doesn't get up until nine or ten; but I never knew grandfather to go away without saying so. And the blacks are away, too."

"Miss Grandeman!" I interrupted. "Something queer happened last night, after I got back here. Do you know what it was?"

When she shook her head, I told in brief of the happening I had witnessed. She just shivered and looked anxious, but was not at all surprised.

"There have been—things like that before," she admitted. "But I really must go. You will be careful? Take the other road, when you go out? I—I would be rather glad to know there is someone here I—" her face began to color in a fashion which shamed the rouge.

"Call it friends, Miss Grandeman," I said, extending my rough paw. She accepted gratefully, and smiled. Funny, as she turned and skipped to the fence, vaulting over just like a boy.

I hated to think of her having to stay in that old ruin—a place reputed to be haunted even before Old Oyster-Eye came—with that white haired maniac and the speechless blacks. Even a staid widow, such I imagined Mrs. Colman to be, would not be much comfort or protection against enemies of the woods-sorcerer who came with submachine guns.

I resolved to talk things over plainly this very day, with Lavoisier, and try to convince him that I was not on the side of his enemies—or not until I saw some genuine reason, beyond the matter of the fenced road.

But how to get at him? How to send even a message? I regretted immediately that I had not written, and given the letter to Miss Grandeman, but it was too late now. On guard against enemies who would do as senseless and cowardly a thing as fire bursts of submachine bullets through the windows of a house where dwelt two helpless women, Lavoisier surely would have a watch set against me now. He knew where I lived. Probably those speechless blacks were somewhere In hiding, ready to leap out and seize anyone who ventured across the fence. That scene of last night might have been four Negroes in robes, carrying away a prisoner to dump him in a swamp honeycomb, where his body would be cared for quickly by the alligators...

Here was not a place for strong arm methods, I realized. Somehow I would have to get that letter to Lavoisier immediately. Well, no matter how frightened of the Cunjah House and its occupant Lonnie might be, he would have to get in touch with the black guards. They would not harm him if he went waving a flag of truce, and gave them my message to take to Old Oyster-Eye. But when I returned to the cabin, Lonnie was gone.

IT was hard to understand. He had not drunk coffee or eaten breakfast; and normally Lonnie was my notion of one of those gastronomic giants old Rabelais wrote about. Lonnie was always hungry; I have seen him calmly stow away half a loaf of bread, six cold stuffed quail, two giant skillets full of bacon rashers, a dozen scrambled eggs, and a half gallon of black chickory-coffee (he added the chicory himself, to my rather extravagant forty-cent coffee, because he liked the flavor) just as a mild Sunday morning snack.

To come on Sunday like this, argued something peculiar. To leave immediately, while I talked to Miss Grandeman, meant simply that Lonnie had been frightened. Some sense of duty had made him get me out of bed, but then his courage had failed.

I frowned, sat down and wrote my careful message to Old Oyster-Eye, put it in an envelope, and then set out for Lonnie's woods cabin. He was going to have to help me out here, no matter how scared he was.

Not to be poky about it, the trip over and back simply wasted an hour. Three big-eyed pickaninnies played there at the doorstep of the unpainted shanty; and the mother of one of them was there, immediately alarmed when I demanded her man. She did not know where he had gone, if not to my place. I left a curt word with her for Lonnie to come on the double-quick, the minute he showed up.

I never was to see Lonnie Beejum again alive.

Of course I did not guess that. Annoyed and disturbed, I thought of getting the eldest toddler of Lonnie's three-mother brood to carry my letter; but then I dismissed the idea as cowardly. Good heavens, was I letting this nonsense of a conjurer and his mad ideas get me down?

By the shortest route through the woods, which brought me out to the hanging foot bridge over Dog River, and then to the road and gate where I had been stopped the previous night, I hurried to the Grandeman place. I see I have forgotten to state that at one place on Grandeman's and at one place just beyond to westward, it was possible to ford Dog River—but not in the spring rainy season. This was the end of summer, and fords were practicable.

The iron pipe gate was chained, and a new padlock held it. I went straight up, and shouted: "Come! I want to speak to someone at Grandeman's!"

I waved a handkerchief in lieu of a white flag, and held the envelope with my letter in the other. I had my shortgun in holster, but that would not deter Old Oyster-Eye, I knew.

Twice more I shouted. The air was breathless, humid and warm. Beads of dew still dripped from the gray beards of hanging moss, and the lethargic sounds of a forest grown old in waiting for the clean ring of an axe, came to me in an occasional plop or slow rustle of the underbrush. Right over there on my side of the fence a five-months fawn, just losing its spots, fed unconcernedly; but for a long time nothing came from the house. No sound at all, which was ominous.

I called to the Negroes, but none came forward. Impatient at last, ready to risk almost any sort of happening just to see Miss Grandeman and make sure she and her elderly companion were all right, I put a hand on the nearest cedar post, intending to vault.

At that second out from the brush at one side of the faint wood road a small, sidling man came in a hurry. He was short, spare, but nattily dressed—except for a cap which he wore cocked up and sidewise. He was all in gray, and for a moment I saw no sign of a weapon; but then I saw a bulge in the right side pocket of his jacket. Then I knew.

He was a southern edition of a sort of fellow I had seen at the ringside at Aurora many times—and also the one time I fought at Burnham, Illinois, which is not far from Cicero. Not a killer in his own right, not even really a gangster, this was the sort of suave, ingratiating little man used almost always as a messenger by men who do not mask their killer instincts readily.

A coward, of course but probably nursing certain ambitions to be a Bos-well to big shots. The sort of man who will, kill—but only when he is sure that he is safe, and that his master earnestly desires the death.

"Oh, there you are, Mr. Lamont!" he exclaimed breathlessly, smiling and exposing a gap where two teeth were gone from his upper jaw. "I heard you. Mr. Lavoisier can't come just now, but if you want to come up to the house and wait just a few minutes."

"I don't," I said curtly. "Will you please send Miss Grandeman or Mrs. Colman here? I have a message for one of them."

"I'll take it," he offered eagerly.

"Sorry. It's personal. I'll wait till one of them comes, if you don't mind."

"But I do mind!" he said. "I don't want to see you sitting out here at the gate all day and all night. You see, the two ladies have gone down to Mobile. I think they'll be back sometime tomorrow afternoon."

DOWN inside of me came the momentary shiver and drop which I

was to know far more about—the first inching forward of a

terror which was to be even more real because it was strictly not

my business, and because I had no right in the world to appoint

myself the keeper of a girl I had seen twice and spoken to once

for ten minutes.

However that may be, I knew that Miss Grandeman had not intended to go to Mobile when she spoke to me only ninety minutes earlier. During all the days I had been on my five-acre place, I had not once heard the unmistakable sounds, of a starting motor over at Grandeman's. A car may arrive silently; but even the best ones make a certain amount of noise when being started. I did not think that Old Oyster-Eye had a car.

In short, I did not believe that Miss Grandeman and Mrs. Colman had gone to Mobile!

But if not, why could not one of the two come out to see me? And where was Lavoisier and his blacks?

I feigned denseness. "Well, tomorrow will have to do, I reckon," I said, shrugging. "Are you visiting Mr. Lavoisier?"

"Yes, helping him with his experiments," nodded the little fellow brightly, albeit his eyes shifted quickly. They returned to mine instantly, though, and then held their level gaze with an ingenuous steadiness which ought to have deceived me, but for some reason did not. "My name is Jackley; Bertram Jackley."

"I see. Well, tell Miss Grandeman I called, and want to give her a message. She knows where I live."

With that I turned away, strode, along the fence and around the end of It. There was a prickling between my shoulder blades, where I felt oddly certain that little man wanted to put one of his bullets. But he did not try to do it. Probably, like most sneak killers, he was not very deadly with an automatic at any distance above ten feet.

And there was another reason right then why my death was not desired, though I had no idea of it. Had I guessed why I should not be murdered out of hand by some lurker of the thickets, oddly enough I should have felt more worried rather than less so!

Back at my cabin I took position at the side of the one window which looked out toward the rear, where Dog River flowed. A deep apprehension filled me, and the hunch had grown that over there at what Lonnie termed Cunjah House some queer and horrible business threatened the girl, Marjorie Grandeman. She had not gone to Mobile with Mrs. Colman, unless someone from the city had come up unexpectedly to fetch her. That might be; But I had an unreasonable certainty deep inside me that if Marjorie had been leaving, she would have come over to repeat her warning, and tell me where she was bound. I felt instinctively that there was a sort of bond of fellowship between us.

I loaded my double-barrel Parker with No. 1 buck, and donned Shapley's wide web belt heavy with shells which had been there since deer season. Then I went forth to make a circuit of the barbed wire fence Lavoisier had erected.

ALMOST immediately came a discovery. This fence did not

enclose the whole Grandeman place—naturally, since I just

recalled the fact that if it had not been cut up, it comprised

about three hundred acres, probably a half-section of forest.

Most of it had been, cut over in the vandal days of 1905-1910,

when portable mills went through, taking only the choice timber

but felling much more which was left to rot. Only near Dog River

ravine and my little fenced orchard was the forest virgin.

The four-wire fence crossed the road, of course, and then ran for a short distance around to join my own hog-tight barrier. There it ended. There was no mistaking the conclusion. Lavoisier, had intended to stop traffic over his land and to my cabin, and gave no thought to other neighbors.

Also, when he had built that fence he had imagined me to be Shapley, an invalid. For a sorcerer his information was rather out of date.

My woodcraft was rusty from years in and near Chicago, but I followed the fence back more or less in the direction of Lonnie's cabin. God forgive me, I was thinking of handing him a stiff punch on the jaw when I caught up with him.

It was not until long after the affair of Old Oyster-Eye was finished, that I discovered what had made Lonnie come to my cabin and wake me this Sunday morning, then hurry away without even a cup of coffee to warm his gizzard. But the truth I didn't know was that at dawn two truculent men had routed him and his woman from sleep, and subjected them to a snarling questioning concerning myself. Of course the woman, Ceely Baxter (by courtesy Mrs. Beejum, after the easy way of the woods), had been too frightened to tell me this when I started in to growl about Lonnie.

There did not seem to be any sign of life anywhere on the Grandeman place. I wanted just a glimpse of one of those dumb guards, so I could try sending in the letter by a different route. Since the blacks worked for Lavoisier, they would not trust the sidling little fellow who called himself Jackley. Not unless he really was an assistant of sorts.

Experiments! I wondered with a touch of chill what sort of experiments Old Oyster-Eye might conduct; At night school in the physics lab there had been a fellow named Dreckenbach. He was working on the radio transmission of power impulses.

For amusement he rigged up a bullfrog in the laboratory, so it would hop when he threw a switch. Of course it was just the same principle as the ordinary galvanic reflex, but the wireless part made it look truly spooky.

Earlier I had imagined that the tales of Old Oyster-Eye making figures of red clay and endowing them with life were just the usual voodoo mumbo-jumbo made into the miraculous by superstitious blacks. But since seeing Lavoisier face to face, I could imagine him using hypnotism, for instance, or employing up-to-date science in his illusions. The man showed all the marks of a far better education than I had obtained. Why in the world had he chosen to return to the piney-woods, after completing such an education? Surely the mere exercise of power over woods folk could not be sufficient inducement.

Something moved in a thicket just ahead of me. Weapon ready, I waited, but it was only a false alarm. A. razor-back sow with five half grown pigs came out, saw me, and lied with a chorus of grunts.

I spent more than an hour looking for one of the black guards, with no success; and even now, thinking of how close I must have come to certain men who were right there in the woods on a deadly mission, gives me chills across the shoulder-blades. But the truth was I saw no one at all; and the fact that I still lived bore witness to the fact that no one saw me.

I had turned back, ready to go to the gate and shout for Bertram Jackley, and take my chances with him, when it happened—the terrible thing which altered every half-formed plan. It brought me to a dead stop with one foot off the ground, frozen with my gun ready, for all the world, I suppose, like a pointer dog getting the hot scent of a huddling covey.

Piercing and horror-stricken, from near at hand, had sounded a woman's scream of discovery and agony! At the time I did not think of the discovery part of it. I heard only the unmistakable feminine tones, and my heart stopped for a split second. Then shouting in half-articulate encouragement, I turned and plunged straight through the streamers of thorny Choctaw rose, the anise thickets and the oak saplings, straight toward the place where I felt terribly certain someone had set upon the two women of Grandeman's!

MY shout evidently disturbed the woman, for I caught a flash of brown in the brush just ahead, as I came plunging like a stampeding elephant.

If there had been some of those speechless Negroes there, they could have waited and closed upon me; and I would not have been of any assistance to anybody. But the only black whom I found in the little glade above Dog River was Lonnie Beejum. And Lonnie was as dead as he would ever be, his muscular throat agape with a horrible wound which had ceased to bleed, though gouts and puddles of red still steamed everywhere on the ground and branches of the bush.

I stopped, looked down, then hastily around me as I yanked out the pistol and set down the shotgun—the latter weapon of little use in a place where branches crowd up to within a few feet of your elbows and your face.

No help would do Lonnie any good. I called once, guessing it must have been his woman I had partially glimpsed as she ran from the scene of crime. But there was no answer. She probably would hide until she saw me depart, then come back to wail over her dead after the manner of blacks.

The open razor in Lonnie's right hand did not fool me at all. This was murder, not suicide. To begin with, my man of all work was a big, lusty fellow troubled only by a few superstitions. I was paying him more money each week than he normally earned in any month. He had no real worries in this world.

And then, of course, no Negro holds a razor open in a straight line, with thumb and index finger pinching the metal just above the handle. He heels it; and if he wants to cut deep into an enemy, he thrusts the blade a little outward with the knuckle of his second finger. No, Lonnie Beejum had been murdered!

Realizing that Ceely Baxter would bring her friends to help with the mourning and the funeral, I. did not wait there with Lonnie's body, and thus delay them. Promising silently to return just to make sure that some disposition had been made of the corpse by nightfall, I slipped away into the brush, and stopped to listen.

Nothing. Lonnie had been killed within fifteen or twenty minutes, probably. There had been a raw scrape on one wrist which meant a rope. No doubt he had been taken to this spot and his throat slit before he could scream. If he had been bound, no doubt they had found his own razor in a hip pocket, and employed it.

Why had it been necessary for him to die? Because he worked for me, and came back and forth near the Grandeman place? It was as good a guess as I could make, and not far from the truth, either.

Stern anger about Lonnie's tragic, useless death mingled now with an inner panic. I had to find Miss Grandeman, and immediately! This was Washington County, where there were no law officers upon whom I might call for help. Worse by far than Nature's dictum of the survival of the fittest—only mildly enforced in this land—was the law of lead and steel which the hate and greed of men put forward in place of it. Survival of the craftiest and most ruthless, rather.

Very well. For Marjorie Grandeman and her companion, I would revert. There was a considerable amount of Choctaw blood in my veins, and these were my home woods. If I could not get the better of Negro guards, and city nondescripts such as Bertram Jackley, I would deserve a sticky end! From now on I was going to be more ruthless than anyone!

I crossed the fence without challenge, and made my way in the direction of the ruined mansion as quickly as I could go from thicket to thicket, making sure that no one was waiting ahead to send a bullet or pattern of buckshot into my body.

The woods, now with the sun climbing to the zenith, were checkered with spots of light. The air was still.

COMING up to the great bearded oaks which surrounded the

rambling Grandeman mansion, I found easy cover in spite of the

fact that the underbrush thinned. Four of the great trees, spaced

out like sentinels posted for the ages, hung their hundred-foot

umbrellas almost to the ground. From their lowest branches the

Spanish moss depended, making a weird six-foot horizontal zone of

dimness through which men could pass by pushing aside the

vertical gray veils.

I swung up to a limb as heavy as a stuffed python, leaving the shotgun cached under some ground palms. Little by little, I worked a way upward, taking care to keep my body shielded from observers at the house.

I could see patches of the house; three windows black and forbidding. Glass was knocked out of one of them on the ground floor, possibly by that fool who sent submachine bullets into the place.

None of the wild animals and fewer redbirds were up here. A sepulchral silence held every leaf motionless. I found myself perspiring, though scarcely with the exertion. Where could all the people be keeping themselves? I knew, or thought I knew, that at least four Negroes, two white women, Old Oyster-Eye and that sidling little fellow Jackley were inside the wooden mansion. Were they all sleeping after a night of horrid rites and red murder?

I worked along the big branches, toward the house. Now I saw more of it. The place was not enormous save by comparison to the cabins of the piney-woods. It was built like many of the summer homes of New Orleans millionaires at Pass Christian; though in this case a northerner had constructed it as a refuge for both summer and winter.

The house had two sides, separated by a wide hall on both first and second stories. There was a wide front gallery on each of the two floors, screened now with new copper that had not been painted. On each side were two rooms upstairs, and two downstairs.

The central hall downstairs led back to the dining room (which was only one story) and storage loft above, and exactly the width of the hall. Kitchen and sen-ants' quarters were a series of lean-to additions at right angles to the extreme back of the dining room. Thus both downstairs hall (which served as a living room) and dining room got all the breeze there was in hot weather. Upstairs the same was true, though only when a surplus of guests arrived were the bed-chambers on the second floor used in summer. Inland Alabama rarely has a really cool day between May and November.

The exterior was in surprisingly good condition, with new brown shingles showing here and there where repairs had been made on the roof. The whole building had been painted white, which was an odd thing indeed if Lavoisier was just a squatter here as Miss Grandeman thought.

Listening, I could hear no sound from the house. Working my way out along a big branch which overhung the roof of the one-story addition where the servants probably slept, I swung down noiselessly and crept on hands and knees to a second-story window.

It was blank, uncurtained. Chancing a look inside I found out that this was just a storeroom, containing three or four trunks, several suitcases and a couple of boxes which looked as though they might contain books.

Luck was with me. The window was unlocked, and raised easily with only a slight scraping sound. A moment later I was inside, listening, ready to give any one who disputed my presence a grim surprise indeed.

IT took me a long while to realize the fact, tiptoeing stealthily out into the upstairs corridor, viewing another empty room, then silently stealing down the stairs to the main floor, but I was just making trouble for myself. There was no one at all in the house, upstairs or down! Even Jackley had gone!

For some time I refused to believe it, even going down into the basement to search, and opening every clothes-press and linen closet on both sides of the house.

But while I made some queer discoveries, all right, I found no occupant. The kitchen and sleeping quarters for the blacks were deserted, the beds unmade, and breakfast dishes stacked on one side of the sink, ready to wash.

Lavoisier and Miss Grandeman had their rooms on one side of the main building. These two rooms and the big central living room were comfortably though inexpensively furnished, grass rugs on the floors, and the chairs, tables, dressers and couches mostly of rattan or white painted pine.

I cared nothing for details. Marjorie Grandeman and Mrs. Colman certainly were not around; and yet a dull feeling akin to hopelessness made me certain that no such easy explanation as a day of shopping in Mobile accounted for their absence.

There were no other beds in the house proper, save the twin beds in the room where the two women slept, and a white iron cot bed used by Lavoisier in the other bedchamber. If Jackley indeed were helping Lavoisier with experiments, he must come and go each day.

The two rooms on the other side of the living room downstairs had been made into one by removing the partition. Here was a complete chemical laboratory, with high tables, racks of test tubes, shelves of reagents, Bunsen burners, and an array of flasks and retorts. All was plain and businesslike, with no mysterious apparatus. The only remarkable thing I found was an ordinary barrel half filled with ordinary red clay. Was this the stuff Old Oyster-Eye used in making his figures?

Upstairs on this side one room was bare and empty. The other chamber evidently had been used for drying a crop of pecans, since several open boxes were filled with these nuts, and a foot-deep heap of them lay loose in one corner. They were the finest Schley paper-shells, and I wondered where they had come from, since I was quite sure there were no such trees on the Grandeman place.

They were to play a curious part in the affair of Old Oyster-Eye, though no one guessed the fact until it was almost too late.

My investigation had come straight up against a blank wall. What connection in the world could the murder of Lonnie have with the disappearance of these two women and old Lavoisier? What part did that soapy little fellow, Bertram Jackley, have to play?

Of course matters could not be left like this. Lonnie had been murdered; and affairs were in such shape at this old place that serious fears for the women were only common sense. I decided, to get my Ford and hurry down to Citronelle. At that town someone surely would know whether or not a car bearing Mrs. Colman and Marjorie had passed through; the only highway to Mobile is the main street of Citronelle, and machines coming down from the woods are few in number at any time.

If no car had been seen, I meant to get myself a companion. There were three or four young men friendly enough toward me the time or two I had spoken with them since my return to the woods. One of them might take on the adventure of coming back and helping me investigate. I had little desire to go to sleep up there in my cabin now, with no guard posted.

THIS plan eased my worry somewhat as I hurried back through

the woods, seeing no one and hearing no sounds which would make

me think there was any human being within miles. But I was not to

go to Citronelle now. The grimmest sort of surprise awaited.

I had crossed the river and climbed the hog-tight fence, careful about the shotgun recovered on my return trip, and was taking a good look at my own cabin for signs of visitors, before emerging to the bare dooryard.

The small, corrugated iron garage was just beyond, and Shapley's old Ford inside. And now sounded from there a long sobbing honk of the horn I Somehow it sounded like, desperation and misery. I know it was not until later that I realized how easily it could have been a decoy. However, taking the shotgun off safety I hurried straight to the garage. The doors stood open; and down there on the threshold was a red splash which could only be fresh blood!

It was old Lavoisier, terribly wounded and crumpled there against the running board. He evidently had crawled up and sounded the horn, slipping back then as his strength failed. He was clad only in shoes, trousers and a shirt which had been white. A wide red stain began between his shoulders; and there was a corresponding stain in front, high at the left. From the tears in cloth I saw at once he had been shot from behind, and the bullet had gone straight through.

He was breathing faintly, though I could not make out any heartbeat. Lifting him gently I carried him into the cabin, hastily barring the two doors and pulling down the window shades. Then I heated some water and some black coffee, and undressed him to the waist.

It was easy to stanch the blood on the outside, with a pair of compresses; but looking at the seamed, chalk white countenance I felt very little hope that any measures were going to do much good. He evidently bled internally, froth appearing now at the corners of his mouth, and showing a tinge of red.

Perhaps the most terrible part of the three hours that followed lay in the fact that I could neither leave him to ask someone like Ceely to send for a doctor, nor could I bring Lavoisier to anything like complete consciousness. The words he spoke did not seem to make sense—at first. And the bloodstained envelope he poked at me, whispering that I must rescue Marjorie and give it to her, contained one single sentence in a pencil scrawl, one which surely sounded like the ravings of delirium! This is all it said:

Marjorie dear, your heritage is black instead of white, and your pet squirrel rejects it with scorn.

J.L.

Now honestly I ask you, what could anyone make of that?

Between my own terrible anxiety over the fate of the two women, my attempts to resuscitate Lavoisier so he could speak and tell me what I must do, it was an anguished time. The old man, no longer malignant, but weak and rambling, when I did get enough of the coffee into him so he tried to speak, would say a few words—only to lapse again into faintness.

Because there can be nothing but sadness in trying to reproduce these last minutes of one thoroughly misunderstood, I shall give simply the fragments of speech and whisper which I did manage to glean from his lips.

A man named Breen had betrayed him. Breen had been a partner. He had captured Marjorie (no mention of Mrs. Colman). The blackguards were dead...

WHAT this could signify, more than a kidnaping for possible

ransom, I could not imagine. But it did not seem that this was

the idea. Or at least there was more to it than that. Over and

over I begged Lavoisier to tell me where to find them. And I

obtained only a mutter about Dog River Cave. If there was any

sort of a cave down near this stream, I certainly had not heard

of it; but those three words were plain enough. Which way did the

cave lie? I repeated the question again and again, but got

nothing more. The dying man seemed to think that I knew all about

it; or else his mind was rambling.

That was all which bore upon the terrible plight of Marjorie Grandeman and her companion; but there was one other thing which seemingly was wrung from Lavoisier at the very end. For some time his breathing had been bad, and no heartbeat at all discernible, Only the slow and uneven rise and fall of his chest showed that life had not fled. I tried him on a last swallow of the tepid coffee.

Then it was his eyes came wider, and he seemed to struggle to speak. I put an arm behind his head, and saw his black eyes fixed upon me in an agony of striving. Then words came!

"Save her... and give her that... she... understand!" came the hoarse admonition. "You, my grandson... daughter married... scoundrel... Lamont... you... do this... or I'll come back... from grave... to curse you!"

"I'll do it! But where is Marjorie?" I cried, quivering with the terrific news I had just received—if it could be true!—but demanding that this last minute be given to helping me search for his ward and Mrs. Colman.

It was too late. Jules Lavoisier, as I later discovered his full name to be, died in my arms.

I was left to my desperate, almost hopeless search, and to the breathtaking knowledge that I was said to be the grandson of this strange, inexplicable character! That instead of being a nameless Cajan orphan, I boasted a father named Lamont, a scoundrel whom my mother had married!

REASON was all I had to fall back on; and in the first place, reason rejected the idea of any sort of cave in this neighborhoods Southern Alabama is all red clay and sand; and natural caves do not do well in either of these materials.

A little further north, where sandstone and' shale push up in the hills; there are said to be some natural caverns where water dissolved out all the limestone which once was present with the other kinds of rock. It was up there that I always supposed the sorcerer. Old Oyster-Eye, dwelt. Some of the woods folk no doubt knew more exactly, but that mysterious cave of skulls up somewhere in the hills had made a good story, and I had believed it to a certain extent.

Now to find that this sorcier had been my flesh and blood grandfather! That explained his recognition, and his violent words there at the gate. No doubt he had disowned his daughter; and looked upon me as another Lamont, to be hated. But why, if there had been a marriage, was Lamont supposed to be such a scoundrel? There never had been a man in the woods by that name in my boyhood. Possibly he had died in prison; and the disgrace of what he had done was so terrible that my mother had preferred to deny her own marriage!

These hectic thoughts consumed me as I covered the old man's body with a sheet, and hurriedly slipped out to begin the search I felt was well nigh hopeless. There was little choice between upstream and downstream until I chanced to recall that the Grandeman acres themselves stretched upstream. Shrugging, keeping alert for the slightest sound of any other man who might lead me to my goal, I therefore started through the woods above the ravine, peering over to search every yard for a sign of the cave.

That did not work. Between big trees and underbrush, the sides of the ravine might have harbored a cave mouth every hundred feet, for all I could tell from above. There was nothing for it save climb down and make my arduous course along the bank, wading where the thickets could not be penetrated.

It seemed dark down here. One glance at my wrist watch and I had a sinking feeling of hopelessness. Four in the afternoon! While I had been caring for old Lavoisier, the day had melted away. If I could not find where Marjorie and Mrs. Colman were held prisoners, and do it inside the next hour or so, night would be upon me!

The first discovery I made was down in the bed of the river, perhaps half a mile above my starting point. It was plain sign of extensive human activity, though for the first moments I could not imagine what sort. Mining of any kind, you see, placer or hardrock, is unknown in this section of the State; and I never had come upon this sort of layout elsewhere.

It consisted of what I thought a purposeless flume, but which really was a wooden sluice with many baffles, not unlike the affairs used in Alaska in the old days of the Klondike rush. There were long handled shovels lying about, rusted, but nothing else. I finally got the idea and looked dubiously at the river. I doubted very much that it contained gold, though that might explain a number of things.

HAD Lavoisier been engaged in mining—or alchemy of some

curious nature? The barrel of red clay there in his laboratory

might have had some connection, though I did not believe it had

come from the river. Lord knows there is no dearth of red clay

anywhere in this part of Alabama t I make no excuses. I must have

been so interested in looking for a cave in connection with this

sluice exhibit, that I failed to pay attention to the bank behind

me.

"Hit!" came a raucous shout, and then heavy bodies struck me from the rear, bearing me down and pinioning me as I fought with all strength to win free long enough to use one of my weapons.

No use! Soaked with mud and water, half drowned, stunned by the kick of a heavy boot against the back of the head, I was disarmed and bound—by four darkies!

Yes, these were the same ones Lavoisier had told me were dead; and now they served another master, a more or less white man with cold blue eyes and a heavy jaw which he had a trick of pushing forward till his teeth showed like those of a bulldog!

I guessed this must be Breen, though I did not intend to let him know I had heard anything from anyone.

"Just what in hell does this mean?" I raged, as soon as I could speak. I was being dragged uphill by two of the blacks, who did not even bother to lift my shoulders, but hauled me by my bound legs. My head bounced until I managed to stiffen my neck.

"Wait and find out—Lamont!" said the blue-eyed man. I saw now he was attired in city clothes; a suit of reddish-brown heather mixture, white shirt, blue tie, brown Homburg hat, and only the knee-length laced boots being a concession to the shakes other than human he might meet in the woods. He had no weapon in sight, but a bulge at his left lapel told me that he had a gun in a sling.

Somehow I hated Breen at sight, feeling even more ready and molten hate than I had for one who would capture two women, probably maltreat them, murder Lavoisier, and now doubtless murder me as one bent on interfering with criminal plans. He was cold, ugly and more than a little masterful without having to descend to being a common bully. I hated him by instinct, and should have done even had I only met him a number of times in polite society. He looked to me like a man of education who was going wrong just because it pleased him to do so. Certainly he was no gangster type, as I had got fairly familiar with it in the north.

The four Negroes spoke no word after that single shouted "Hi!" which had been the signal for them to set upon me.

Only a few yards up the bank the blacks halted a moment; and then I found out how small a chance I ever would have had to find the cave mouth. Two Negroes leaned forward, facing uphill, and looking as though they intended to pull up some tangled dewberry bushes by the roots.

Instead of that, there ensued a clanking, scraping sound, and a slanted wooden trapdoor, sodded and camouflaged with live bushes, came up easily enough to horizontal. This made an open doorway into the hill behind. The doorway was only about five feet six inches high, but six or seven feet wide; and inside the room beyond, a light burned and two white men—one of them Bertram Jackley—came to make sure who it was that entered.

The door was counterweighted; and when it was set at horizontal a pole like the center pole of a tent was set under to hold it in that position.

I was picked up now, carried inside, and tossed on to the bare clay floor at one side.

"No sign of the old man," said the man I took to be Breen, in a quiet voice. "Lost the blood trail. Tomorrow Tiff can bring his dog, just to make sure. We'll find him dead in some branch."

Tiff, I took it as he turned and looked about, nodding mutely, was one of the four Negroes.

ALL this time I had been staring about, taking in the strange

surroundings, but vastly more interested in finding out if

Marjorie and Mrs. Colman were here. At first there was no

indication that they were.

Some torrential rain and washout probably had dug a deep gully down this hillside in past time. Old Oyster-Eye, or whoever it was that finished the place, shored the soft walls and ceiling with tree trunks, no doubt filling in earth and shrubs on the roof just as had been done with the concealed door.

The place did not look too reassuring, with some of the shoring down and places showing where rain had brought in cascades of red mud. Though once it no doubt had been safe enough, lack of care made it now into a trap where a wise man would not think of sleeping in a rainstorm. Probably that was why Lavoisier had abandoned it to go to the Grandeman place.

The four Negroes squatted down near me. They seemed to have no domestic duties here; and in the first chamber where I lay there were no signs of eating or cooking, or even of sleeping.

There was a narrow passage, half blocked by a fallen timber and cave-in of mud, leading back into the hill. Beyond that evidently was a second room, possibly more, since the man I took to be Breen went back through the passage, out of sight for a minute.

Little Jackley lighted a cigarette with a nervous, apologetic air. He avoided looking squarely at me. It was plain that without the presence of his boss he was timid—even when there was nothing in the world save a bound, unarmed man to frighten him. I longed for a chance even to talk to him alone, but I was never to get it.

The third man, who was attired in a sleeveless jersey, was dirty and needed a shave. He had a belt and gun in holster about his paunchy middle; but I saw from the gnarled muscles of his arms and the broken, black-rimmed nails on his wide hands, he would use his strength in a knockdown battle more naturally than he would turn to firearms. I put him down as a Gulf Coast dock-walloper used to bossing Negroes.

"I'd like to have someone tell me what this means!" I rasped harshly, glaring at the little man in the cap.

At the first sound of my voice I heard a gasp from the adjoining room, and my heart sank. The women were captives there. Though I had never really doubted it, I had hoped that by some miracle they might have effected an escape at the same time as Lavoisier.

Jackley shrugged. "Don't ask me," he said with what was almost a giggle. "The old man cheated my boss, and now Mr. Breen feels that he—"

"Silence, out there!" thundered the menacing voice of Breen from the inner chamber. He reappeared at the passage, frowning. "I'll do the talking, Jackley. You, Corkhill, bring Tiff and another Negro. This damn roof looks as though it might cave in any minute. See... that timber there has got loose, and the whole side..."

HERE cries from Marjorie Grandeman, and screams of hysterical

terror in another feminine voice, drowned out the rest he said.

There were sounds as of clods falling, and I waited, tense,

guessing that the three men were having a hard time making any

kind of a repair in the shoring.

Catastrophe! Whatever it was they tried, failed. With a rending noise of spikes being drawn from wood, came the heavy, awesome thunder of tons of earth slipping. There was a shriek of pain and an "Oh Lawdy! Oh—ugh!" from one of the blacks, choking cries from the women who doubtless lay there helpless to save themselves, and a steady rumble of cursing as Breen strained savagely to stop the minor avalanche.

In vain. Of a sudden his voice shouted imperative commands. Jackley stood up, made for the doorway, and stood there just outside, trembling and chattering his fear. The two remaining blacks were divided in courage. One of them, the whites of his eyes showing, uttered a wild yell, pointing upward where a part of the saplings of the ceiling in this chamber were bulging, and made a wild dive, gaining the doorway and pushing past Jackley.

He kicked over the electric bullseye lantern as he went, but fortunately for every one inside the caves, it was not extinguished.

I had not been tied up especially tight or cruelly, considering the nature of these men; but the work had been done by a Negro used to fishing for catfish, and it was an efficient job. Two loops of line strong enough to land a 60-pound cat held my ankles. My wrists lay one along the other in back, with a loop of the heavy green fishline for each wrist. Only a single strand held the loops together, but it might as well have been a ship's hawser tied with a Gordian knot.