RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

Argosy, 3 November 1934, with "The Stained Tabu"

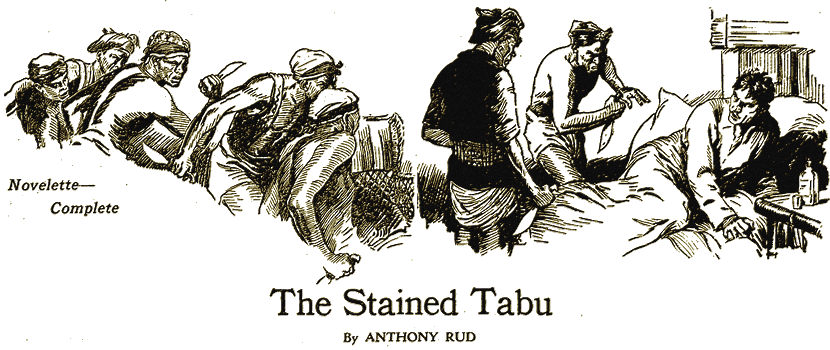

Around his bed were small, half-naked men, each holding a drawn parang!

No man could reach the virgin pearl lagoon because of

King Sakita's ban—so Behrens, the pearler, decided to poach.

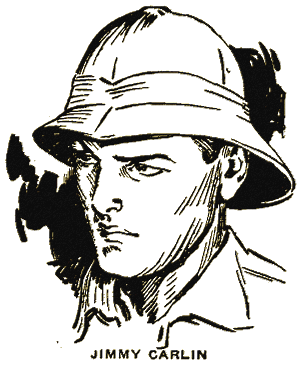

"THE first year's stores are below. I'll have them ashore for you by sundown." Jimmy Carlin spoke slowly, for the Bugingoko of the Burdett Islands is tricky on the tongue. He extended the pen-written sheet and his own fountain-pen. He had read aloud the agreement, which was brief and inscribed both in English and in the vernacular of the islands.

"Sit down and make a mark—here," he invited, indicating the space at the bottom.

"No," said the little brown man in the serang.

He remained standing, his coffee-colored eyes holding those of the surprised. Jimmy Carlin in what seemed a gaze of wistful sorrow.

Jimmy caught his breath. There was no evading the finality in the voice of King Sakita. And save for queer rules enforced in a spasm occurring about once a decade by the Portuguese of Timor, the decisions of Sakita were obeyed unquestioningly and always by the inhabitants of forty-odd fiyspeck islands scattered in the Flores Sea.

The inhabitants of those scattered islands numbered less than two thousand, for a curse had fallen upon them. Always these coral atolls had been poor; but life was easy enough as long as edible fish swam in the sea. Of late years, for a reason unknown to man, the fish had become poisonous. The subjects of King Sakita starved-slowly—or died suddenly with distended bellies and blue patches on the skin.

Not always, of course. Sometimes for a few weeks the fish were all right, then suddenly they would make deathly ill or kill every one who ate. It could not be explained on the basis of spawning season, either; and so actual starvation had come to the Burdetts.

"You realize wh-what you're saying?" demanded Jimmy, stammering slightly and paling beneath his layers of salt-cured bronze. "I was given to understand that you agreed. I have brought five hundred cases of steel-head salmon, five hundred cases of red whale meat, six barrels of nigger twist—"

The little brown man stiffened. He held up one hand in dignified gesture. "I do not make bargains with liars," he explained simply.

Now Jimmy reddened more swiftly than his color had ebbed. "Explain that, Sakita!" he demanded sharply. "When have I ever lied to you or treated one of yours unjustly?"

"Never,"'admitted the little king. His slanted eyes narrowed with a gleam of anger, however. "You held back part of the truth, though. You did not tell me that you bargained not for yourself, but for another. A man I hate and shall kill!" he ended.

That was a stiff blow. Jimmy's eyes fell, and bitter curses welled up in his heart. But then he gained control of himself and arose quietly.

"How did you know I came here in behalf of Behrens?" he asked.

For a long moment the slanted eyes looked scornful. Sakita smiled bitterly.

"When that one"—he spat overside—"comes to the Flores Sea, the word is brought to me. Now he is waiting on Tubu-Muna, at the grove where my people worked for you in cutting and drying the copra—in the days when you were an honorable man and feared not to tell the whole truth."

This was making a terrible thing out of what had been no more than a choice of evils—for Sakita, who would have no choice. Jimmy did not feel guilty at heart. He had accepted the help of Rudolph Behrens long before he as much as suspected that the man was other than he seemed, a pearler and island trader grown rich through lucky finds, and inclined to generosity and kind-heartedness toward young men not so lucky.

BUT Sakita had seen the whole net of intrigue as if Jimmy himself had known it from the first. In fact, as if Jimmy himself had suggested this method of trying to pull the wool over the eyes of the island chieftain.

Something would have to be done about it at once. Sakita had been a good friend to Jimmy two years before "the Cock-eyed Bob" had howled up out of the Indian Ocean, to bring ruin to his little plantation on Tubu-Muna.

"Look here, Sakita, I'm not threatening. In a way I'm damned glad that you saw through my little pretense. I hate appearing to lie. But do you realize that Behrens can ruin you once and for all—and will surely do so if he discovers he can't make a profit out of your pearl lagoon?"

"All he must do is inform the Portuguese at Timor. I know," nodded Sakita. "They will swarm down hungrily, violate tabus, snatch, steal—and destroy any of mine who dare protest. Very well, let it happen. I shall not bargain with Behrens!"

With flashing eyes and a swirl of his rich serang, King Sakita turned to the rail. He gestured, and two broad-shouldered brown men with the high cheek bones of purer Malays stood up in the stern of the long proa.

Sakita placed one hand on the rail and vaulted into their waiting arms. As he seated himself with dignity, the long, narrow sailing canoe drifted from Jimmy's anchored schooner. Then a lateen sail bellied in the breeze, and the swift proa departed. King Sakita did not glance backward.

Jimmy Carlin turned away, growling an order to his flat-faced boatswain. This then was the end. Complete ruin, an end of the last chance to repay Rudolph Behrens, and what was worse, a reputation for treachery. The little brown potentate had been a friend.

Well, he was done with Behrens. Even when the elder man took over the schooner, the ruined plantation, and everything else Jimmy owned, there still would be the debt of more than one thousand English pounds.

Jimmy would give him a note, and then devote his life to repaying. What chance would a beach comber have, though? In these latitudes white men either held absolute authority in their little spheres, or else they were the lowest of the low.

"All that is a trifle," gritted Jimmy to himself. "The worst is the smirch on honor—because I half earned it! Wonder what that wily devil Behrens ever did to Sakita, anyhow?"

HER hatches filled to the covers with canned salmon, the beef-like whale meat (which tastes more fishy than fish), black, braided tobacco in barrels, bolts of flowered calico, and cases of a rather superior gin, the twenty-four-ton schooner Kota Baroe threaded the channels amid the thick-dotted islands and atolls of the Sea of Flowers. Breezes were light and fitful. The Kota Baroe made no more than three to four knots steerage way.

From the southeast, pursuing at twice the schooner's rate, came a single-outrigger proa, single sail leaning, and a tiny white wishbone in the teeth of its slender bow. Hopeful for a second that this might be King Sakita, come to admit handsomely that he had been carried away by wrath, and had blamed his white friend more than justly, Jimmy got binoculars from their case and studied the flying canoe. Then he shook his head. This was a smaller proa, holding only four figures. It did riot interest him.

An hour later, though, he learned that the four brown men in the little vessel sought him. The canoe drew abreast, and a high-pitched voice called his name.

Jimmy recognized the man, and somewhat reluctantly gave the order to heave to. This was a cousin of Sakita, who was the minor chief of three small islands. A far different sort of man—-probably with some Chinese blood tincturing the Javanese and Bugi, since there was a decided yellow cast to his skin. A lazy, pudgy fellow, Jimmy recalled, from copra days. A schemer, whose sense of proprieties was adaptable, as long as he himself ate and drank of the best. He bore the name of Gunong Api.

Now, Gunong Api had no difficulty climbing over the rail. He was thirty pounds leaner than when Jimmy last had seen him; and the enforced banning on his starvation islands had not increased his handsomeness. He looked lean, crafty, mean, even when he bowed in ceremonial greeting to Jimmy, and spoke the flowered phrases of the court language—a stilted lingo abandoned at once, when there was any business to be done.

From the first, Jimmy sensed something evil. For that reason he made no move to entertain Gunong Api, but met him at the rail with a nod for the ceremonials, and then a curt question in Bugingoko.

"Why is my poor vessel thus honored?"

Gunong Api smirked, and Jimmy saw the Chinese in him more plainly. Biting down on the stern of his brier, Jimmy leaned on the rail and waited, wondering what could be in the wind. He had nothing now to lose—nothing save self-respect and honor, that is. And it slowly developed that these were just the intangible commodities in which Gunong Api intended to traffic!

"It was brought to my ears that disaster must come to the Flores," said the Bugi, with a sorrowful shake of his head. The beady eyes gleamed watchfully, though. "My cousin, the great Sakita, has allowed his pride to come before the welfare of his people. Now, Tuan Behrens will be angry. The Portuguese will come. For us will be tapu ailong—e mate! (Broken tabus—death.)"

"And so you're going to do something about it, eh?" mused Jimmy, frowning. "Well, what?"

"You have almost all the stores for the consummation of the agreement—even a new agreement!" suggested Gunong Api suavely.

"Eh?" asked Jimmy, starting erect. "How do you mean, almost? If Sakita had been willing—"

"Ah, but he is not willing! All on account of that wahine, his one-mother sister, who went willingly with Behrens."

"So that was it," nodded Jimmy

He knew the fierce loyalty to mother-kin, even among these polygamists. Behrens, it seemed, had lived with a brown girl, and unfortunately she had been the real sister to Sakita. Well, Jimmy did not like that practice, but it had been very common, out here where there were no white women at all. Behrens sank no lower because of it than hundreds of his own kind of white skin. After all, the girl had been related to royalty; she doubtless had been' small, beautiful in a miniature way, and silly enough to pride herself on a white mate.

GUNONG API shrugged. He went on, admitting that he cared not at all concerning the fate of the wahine, even though she had been related to him. It was most unfortunate, though, that she had disclosed to Behrens the secret of the tabu island, and the untouched pearl beds that lay' between it and the barrier reef.

"That's how he learned," nodded Jimmy grimly. The girl had been a fool, he thought. Long ago the predecessors of Sakita had learned their bitter lesson from white men. The latter would kill a hundred natives for the sake of one large pearl, and think, the exchange of blood for beauty justified. For decades, then, the islanders had hidden or kept secret any pearl bed, fearing the coming of the swarms of whites in their little eight-ton schooners; the destruction and death they left in their wake.

Sakita had been wise indeed. He had ordained a tabu on the little island where the virgin pearl bed lay. That meant he had moved the handful of inhabitants elsewhere, and decreed death to any one who set foot there again. Knowledge even of the pearl bed quickly died in the natives. It had been kept-only by the royalty.

Behrens had been afraid to poach, for that would have brought Sakita with all the fighting men he commanded, and almost certain death. In this time of widespread poisoning and starvation, though, he had guessed that Sakita would lift the tabu for a fortnight each season, in exchange for food supplies sufficient to bridge the times of starvation in each year. And that Sakita would have done, had it not been for the information that Jim-% my Carl in acted not for himself but for the one man in the world Sakita hated most!

Gunong Api professed himself a realist. His royal cousin had blundered. Pride was all right in its way; but when it led to destruction it was a fault. Why should all the others suffer because Sakita mourned the fate of one forgotten wahine?

"So, suppose you get around to it," suggested Jimmy Carlin, tapping out his brier on the rail. "You have an idea, I take it?"

"Ah, yes. I plan to make the same bargain with you—with Tuan Behrens—which was refused," he stated, with calm effrontery. "You will pay me the canned salmon and other things, later. First you will make me a payment of something else."

"And what is the something else?"

"Twenty rifles with brass ammunition!" said Gunong Api. "With those my men can stay out of range of the sumpitans and overcome the warriors of my foolish cousin. Then the agreement will be carried through, the Portuguese will not come, the tabu on the pearl island will be lifted for a fortnight each year, and we will have food, tobacco and gin for the times the fish are bad!"

"I see," said Jimmy, restraining the ire that was rising in him. "Then you—er—will take the place of Sakita, I suppose?"

Gunong Api smiled and shrugged. "If I am successful, and it is the will of my people—" he began pompously.

"Well, I won't have any hand in it! Get out!" said Jimmy suddenly. "Damn you for a slimy scoundrel! Get back into that canoe, or—"

A shout of alarm from Kuria, his own boatswain, brought Jimmy up short as he raised a fist in threat. The Malay was standing near the anchor chain, petrified with sudden terror.

OUT of the tail of his eye Jimmy saw the reason. The three Bugis down in the proa had lifted sumpitans! Two of them aimed at Jimmy himself, while the other trained his long blowtube on Kuria!

Quick as thought Jimmy dropped to the deck, and the two poisoned darts sped over the rail to fall harmlessly in the sea beyond. Jimmy caught the slender brown ankles of Gunong Api, lifted, and heaved. The plotting assassin went head first over the side with a wild scream, splashing into the water and immediately being clutched by one of his men. The proa drifted away, with one of the brown men setting the lateen sail,

A shouting came from the four members of his crew. Jimmy scrambled along on hands and feet a few yards, before ducking up his head for a quick glance. Then he stood erect. The proa was now beyond blowtube range, and something terrible had happened aft

Jimmy let out an exclamation of rage. There, back against the capstan, slumped Kuria, hopelessness in every line of his figure. As Jimmy reached him he plucked forth a feathered dart from his upper arm.

Jimmy sat down on the deck, jerked off his shoes, and yanked the laces out of them. With these and the handle of his knife he fashioned a rude tourniquet, which he swiftly applied to Kuria's arm above the wound. Then, calling for another knife from one of the brown sailors, he slashed down into the wound until red blood welled. Putting his lips to the cut, he sucked and spat. Perhaps there was a chance to save a life.

At fifteen-minute intervals he loosed the tourniquet for half a inmate, immediately tightening it again. He called for a bottle of gin from his own cabinet, and gave Kuria two-ounce doses of this straight. The native lapsed into languor, occasionally groaning feebly. But when an hour had passed, Kuria was still alive, and sweat stood out in great beads on his skin.

"He will live now, I think," decided Jimmy, removing the tourniquet. He upended the gin bottle, to wash out the taste of blood and blowgun poison from his own mouth. "Where did that rat, Gunong Api, go?"

Silently one of the sailors, his eyes still round with the miracle of recovery from sumpitan dart poison, pointed to the north. The proa was no more than a tiny dot on the horizon, bound on the very course Jimmy himself would lay.

"Naturally he would go to Behrens, damn him!" swore Jimmy Carlin. "The swine will get there hours before we possibly can. There'll be hell to pay!"

SURPRISINGLY, now that he realized that Behrens had made-a pawn of him in a dirty, game of deception, Jimmy Carlin could call to mind many incidents which showed a seamy side to the character of Rudolph Behrens.

While a strong sense of gratitude had obscured his judgment, Jimmy had been blind to incidents that testified to what the Dutch called schlimm traits in his employer.

That time he refused to go to the assistance of Bennett, on Tofoi Isle, when the trader was besieged by a whole tribe run amok on contraband bhang.

Jimmy himself had been away at the time. It was only months later that he heard the circumstances; and then Behrens had a far different version.

Now as the Kota Baroe neared the island of Tubu-Muna at sunset, Jimmy Carlin was in the bow with binoculars, searching grimly for sight of the proa. It was not in evidence—though that did not mean much, as there were two other harbors possible to light craft on Tubu-Muna. Jimmy did not waste time to reconnoiter.

Lowering a skiff, taking one of the Malays, he made for the broad beach. Through the brush, beyond the few slanted palms left by the screaming wind which had ruined his plantation, he discerned the thatched roof of his repaired bungalow. No lights as yet. No sign of human beings. He leaped out into the shallow water, strode to the white beach, and made his way inland.

His heart was throbbing in his throat. Had Gunong Api managed to state his treacherous case well enough so that Behrens had given him the guns and ammunition—perhaps even taken Behrens's own smaller schooner and started on a murderous raid which would overthrow Sakita and open the way to a rape of the tabu island and its bed of pearl oysters?

Behrens evidently had been told of the schooner's arrival. He emerged to the screened lanai just as Jimmy came. Behrens was freshly tubbed and dressed in whites.

His face was ruddy, with that faint purplish cast which tells of self-indulgence in the tropics; and he scowled at sight of Jimmy.

"I have heard of your failure," he said in greeting. "Gunong Api has been here. What the devil got into you, anyhow?"

He slammed back the screen door irritably so it banged. Jimmy entered, and tossed aside his pith helmet.

"Has that rat gone?" he demanded curtly.

"Gunong? Why, yes. He seemed in a good deal of a hurry—didn't wait longer than to ask me if I'd give him twenty guns. Naturally I'm no such damn fool. He'd start no end of trouble, and prob'ly end by turning the guns on us. Treacherous devil. But, come and have a spot and tell me what in hell happened. I thought you said that deal with Sakita was in the bag?"

FOR the space of three heart-beats Jimmy stared, all his wrath against Behrens oozing out of him. The man seemed natural—a trifle upset, of course, because Sakita had not let himself be outmaneuvered, but not unreasonably so. Jimmy found himself arguing inwardly for the man who had helped him.

Behrens, after all, had been offering an honest exchange to Sakita. A fortnight of diving each year—the oysters to be rotted elsewhere—and in return for the shell and a problematical number of pearls, provisions and drink worth a. full four thousand American dollars each year.

"It was all right, and a sealed bargain—except while I was getting the canned goods Sakita heard from one of his agents around, here," said Jimmy, dropping into a deck chair and helping himself to gin and limes. "That spilled the beans."

"It seems you had the nerve to run away with Sakita's one-mother sister, some years ago," he ended grimly.

"Oh, hell!" growled Behrens. "Yes, that's true enough. But I treated her decent. She never complained! I didn't have even a hunch that Sakita gave a damn, till one time he sent a hundred of his blowgun artists after me; one time I'd anchored near. And he still cherishes that grudge, eh? I hoped he'd forgotten by now, but I sent you so's not to take any unnecessary chances."

Put in that fashion, especially since he had dismissed. Gunong Api in a hurry, the trouble did not seem very important to Jimmy Carlin. Sakita, of course, made a fetish of family honor; but he would have felt just as disgraced had Behrens married the brown wahine that long time ago. It was a matter of keeping, the royal strain pure, more than any abstract morality.

"I've made up my mind to something," said Jimmy nevertheless. "I'm going to make out a note for what I owe you, and slide out for Broome. Maybe I can get a schooner for the season, and make a start at repaying you?"

"What?" Behrens scowled. "Why the hell should you be dissatisfied, huh? I promised you a quarter of the profits on this agreement—"

"Which I didn't put across," Jimmy finished for him. "It finished me with Sakita, too. Oh-h, I don't suppose I could explain h, but I'm through. You've been mighty good to me, but I've got to get out on my own—and in a different part.. I've always played square, but just according to the way Sakita feels now I'll 'always have a dirty mark against my record. And I don't like the idea of that

"Wait! I'm not blaming you—much. It's just that things have broken all wrong. And I couldn't stand it, having them all saying that I was here just to do your dirty work for you!"

He got up, tossed the remnant of his nightcap drink, and went to his own chamber.

"Aw, hell. Get a good sleep and you'll feel different," came Behrens's careless adjuration through the thin walls.

But the elder man's face was set and ugly. Losing an agent known for his personal squareness would be a harsh blow to him. The time had passed when Behrens himself could trade personally in the Flores Sea. Still scowling, he got up and opened a fresh bottle of gin to take with him to bed.

It was past midnight, with no sound on the island save the faint roar and resurge of surf on the outer reef, and the fainter whine of monsoon through the pom-poms of the few remaining palms.

Two proas came silently and furtively to Tubu-Muna. The first was hurriedly beached, as its four occupants seized long packages and carried them up the beach to be hidden in the grass. Then the four men hid themselves, each one holding a level Winchester rifle.

The second proa held nine small brown figures. They did not hurry, but carried one of their number through the shallow water. Then they melted out of white moonlight, to the checkered shadows of the brush, moving toward the thatched bungalow on the other side of the island.

It was Behrens's habit to go to bed well soaked in alcohol, then to wake up on the average of each two hours, take a long gurgle of gin from the bottle on the floor at the side of his bed, and go back to sleep. Thus far he had not been troubled with horrid visions—pink elephants and azure camels—though his nerves were jumpy and troublesome when he was forced to delay his usual stimulant.

NOW he awoke with a start, and blinked. Surely this must be what men feared when they spoke of tremens! Here around his bed were small, half-naked men, each holding a drawn parang! From the stern expressions of their countenances there could be no doubt at all of their readiness to do murder!

Behrens's hand went automatically for his bottle. But midway it froze.

"Get up!" bade one of the little brown men.

And with a sudden shiver Rudolph

Behrens recognized King Sakita, brother of the wahine the white man had stolen years ago—and strangled when he tired of her!

Rudolph Behrens had courage. Wakened thus, however, and needing a drink—or believing he did, at any rate—he was far from at his best. Shaking, his teeth chattering, he got his bare feet to the floor and stood on them, although his knees smote together. He was certain death was coming, but there was nothing he could do. Nothing save fall down and beg—and even Behrens scorned that. With the parang pricking his back he let himself stumble into the adjoining room. There Sakita faced him.

"I had sworn to kill you, Tuan Behrens," said the little brown potentate, without preamble. "I should have waited, though, until you transgressed in my territory again.

"But trouble has driven me here. I have decided either to kill you, or to exact the most sacred promise of white men from you."

"Promise?" shivered Behrens. "I'll promise anything!"

"And keep that promise—if it means never telling a living soul that there are pearl oysters in the lagoon of my tabu island?" The native's voice was stern.

"And keep that—" began Behrens with vehemence.

Outside the latticed windows sounded a high-pitched snarl. Gunong Api had crept up with his three renegades, and had heard how his cousin was emerging from his dilemma with success and honor. It was too much for Gunong Api. He snarled a command to his three men.

Rifles spat. The fire and smoke knifed through the lattice. No matter that these natives were unaccustomed to rifles; even they could not miss at four paces distance! Two of the nine natives dropped without sound. The figure of Sakita staggered and spun half around. One other of his men screamed and caught at his neck, which geysered red.

Behrens, eyes bulging with surprise and horror, still saw his opportunity. He sprang upon the staggering king, and bore the latter sidewise to the floor. Above them came the click-clack of lever ejectors, and then a second volley of death.

A moment earlier than this, Jimmy Carlin had been awakened by voices. He leaped out of bed, knowing that no one here spoke Bugingoko except in dealings with island natives. And just then he glimpsed four skulking figures draw up to the windows of the next wing of the bungalow, where Behrens's room was located.

Reaching for his own pistol, shoving in a filled clip, cocking it, he opened the lattice shutter of his own window and slid down to the ground, crouching in the dark. Then he crept forward. Something strange and sinister was happening, and he meant to have a hand in it.

The first volley through the shutters into the room lighted only by the single low-turned lamp caught Jimmy incredulous. He gasped, yet still hesitated to turn loose his own automatic. At whom were these men firing? And who were they?

He let go one shot over the heads of the four riflemen, and simultaneously their second volley spattered raggedly. With yells, probably unaware of Jimmy's existence, they reversed the rifles, and smashed in two of the shutters, leaping through.

Amazed, catching sight just too late of the renegade Gunong Api, Jimmy Carlin cried out a warning to Behrens, and climbed through into the smoke-wreathed room,

Shots reverberated, and orange tongues darted. On the floor at Jimmy's feet was his little friend, Sakita, with Behrens choking the life out of him.

Two brown men, drunk with slaughter, and now swinging their hot rifles, got in Jimmy's way. One of them aimed a blow at Sakita—or, possibly, at Behrens; it was hard to tell which.

The automatic leaped twice in Jimmy's hand, and the two islanders staggered away. Jimmy grabbed Behrens by the throat with his left hand, and yanked. The big man came up from the floor, but his small antagonist came also. The grip on Sakita's throat did not loosen.

"Let go! Are you crazy?" cried Jimmy, but Behrens paid no heed.

There was nothing for it. Jimmy raised his pistol, and brought down the barrel sharply on Behrens's skull. His sharp tug then was rewarded. Behrens went limp, and Sakita fell back to the floor.

Instantly one of the king's own band darted forward, seized his senseless body, and ran for it. Three others of the original nine also fled. With screams, and two explosions of unarmed rifles, the remaining pair of assassins took after their prey.

One stopped at the doorway, though. A grinning leer, of hate and balked fury on his lean visage, he threw level his Winchester. A shot crashed—just as Jimmy bent forward to turn Behrens to his back.

Gunong Api had got his revenge for manhandling.

Something struck glancingly across the back of Jimmy's neck, just where it joined his skull. He sprawled over the heavy, man's body, knocked out as completely as if by a hurtling sandbag.

THOUGH Jimmy Carlin had been terribly jarred at exactly the point where the brain is most vulnerable to shock, and knew, it not, the long flying-proa with King Sakita and the remnant of his followers, made its escape:

The riflemen who pursued did not attempt to launch their own craft, since it could be outsailed from the start. They came back to the bungalow, where Gunong Api now was in charge. He handed each a full bottle of white man's gin.

These were received with howls of delight. Rudolph Behrens, who was sitting up, drenching his innards with the needed stimulant, paid no heed.

He was getting more ugly with each passing, moment, and stared with a lowering scowl' at the bound and still unconscious Jimmy Carlin on the floor at his feet.

"You can't have him. Not now," Behrens snarled to his brown confederate. "He sloughed me, an' I don't take that from anybody. Damn prissy fool. Well, he's got plenty comin' now!"

"I will cut out his heart!" spat Gunong Api.

"You will?" asked Behrens, though without denial. He chuckled hoarsely. "There might be somep'n in that, at that. But not now, not now.

"I think we'll all make for that tabu island right off at sunup. I got a grand idea. It'll"—he hiccuped—"it'll work two ways for me. Blood—white man's blood—breaks one of your damn tabus, doesn't it?"

In spite of himself, Gunong shivered, "The blood of any outlander stains a tabu," he answered, with involuntarily lowered voice. In spite of his chicanery, he had all the superstitions of his race. A tabu, though laid by a king or a priest, was supposed to be just as powerful as if laid down in some hoary epoch of the past by one of the fish or air divinities. Even the king or priest had to obey the tabu, as long as it was in force!

Behrens chortled. "Well, that looksh shwell to me!" he croaked, gasping for breath, his speech growing thick with the assault of a full fifth of proof gin atop his potations of the evening. "Two nigger babies with one basheball! You take 'm an' cut his heart out—on the island. That breaksh damn tabu, an' I can dive f'r oyshtersh any time... longsh I want!"

Chuckling, breathing hoarsely, he lurched up, caught the limp bound body of Jimmy Carlin by the collar, and dragged him into =the adjoining bedroom,'locking-the door. Sprawling head first across his rumpled bed, Rudolph Behrens snored.

THE Kota Baroe did not sail at sunup. At the broiling hot hour of eleven Rudolph Behrens still slumbered, snoring away the worst debauch of his many years in the island.

In the living room of the bungalow dead men, wounded and drunken lay sprawled together. Even Gunong A pi had not been able to resist the chance at a free hand with the white man's store of gin. He lay in the doorway of the veranda, mouth open, when finally Rudolph Behrens, eyes bloodshot and in an evil temper, came to kick him awake at noon.

Jimmy Carlin had passed the first stages of nausea and blinding headache. He lay in a semi-stupor, bound, and suffering from blood flashes across his field of vision each time he opened his eyes to daylight.

Almost the first act of Behrens was to come, glower down without speaking, and then stride away abruptly, yelling savagely for a couple of the houseboys. Then Jimmy was lifted, carried down to his own schooner, and thrown, still bound, into the empty cubbyhole of the lazarette. The door slammed and was padlocked. He was in pitch darkness.

Another hour dragged past. Then, muffled by intervening timbers, came familiar sounds—the creak of rigging. The haww-arrr, haww-urrr of an anchor chain, and then the tensing of mast steppings as the Kota Baroe heeled slightly and fled with the fringe of monsoon.

Jimmy had regained the ability to think clearly; but the entire proceeding seemed like a nightmare to him. Had Behrens gone stark crazy with drink? The only alternative was even less promising. The trader had succumbed to the arguments of the renegade Gunong Api. Taking a chance to murder King Sakita, Behrens and his brown-skinned confederate now were on a foray. They would swoop down upon the islands, with the weight of guns overpower resistance, and enthrone Gunong Api. Then Behrens would claim the pearl bed—probably the whole tabu island off where it lay.

"Wonder what his kind thought is for me!" reflected Jimmy. He could scarcely believe that Behrens contemplated murder, since the killing of white men was held by Portuguese, Dutch and English authorities alike as appalling lèse-majesté, as well as an ordinary crime. How keep white control of these teeming millions if white men were shown to be mortals instead of demigods with powerful manas?

Still, he could scarcely let Jimmy Carlin escape. The young man had made a name for himself in these waters; and even now there is no chance for a weakling to win respect. A deep and abiding anger, the slow and relentless wrath of a man so sure of himself he never has needed to bully or swagger, was glowing in the forge of his mind.

The air in the lazarette was stuffy, laden with ancient smells, growing steadily poorer in oxygen. Jimmy had begun to thirst. It surely must be late afternoon again. The Kota Baroe must be nearing her destination, if indeed his guess had been right.

Then came a rattling of the padlock, a rasp, and the door swung open. The first figure was that of Behrens. He carried a pistol, and from the swaying of his walk Jimmy saw instantly that the man had sought a cure for shakiness in a whole tuft of hairs from the dog that bit him.

"Grub and water—though you don't deserve it!" he said harshly. "Come in, Kuria; but no funny business, or I'll smear the two of you!" He waggled the automatic, and backed against a wall of the cubbyhole.

"You're laying up treasures in hell, don't you know it, Behrens?" demanded Jimmy hotly. "What d'you think I'm going to do to you when I get out of here?"

BEHRENS snarled. He stank sourly of gin perspiration, and his breath was worse. "I'll leave it to you—you're a religious fella, an' think about the hereafter!" he retorted. "One thing sure. You won't be mixing in what don't concern you quite so damn much, once Gunong Api gets through with you!"

The brown boatswain, the man Jimmy had saved from the results of the sumpitan poison, went down on one knee. His flat, high-cheekboned face was impassive; but the coal black eyes burned into Jimmy's. They seemed to be trying, to convey an imperative message.

Jimmy put his lips to the tin cup Kuria extended, and drank deeply of tepid water. All the while he was watching the native, but not guessing what Kuria was trying to say with his eyes.

Rudolph Behrens was watching so closely that anything like a whisper, or any words framed by the lips, even, were out of the question.

In his other hand Kuria bore a mess kit partly filled with a stew made of shark meat boiled with cassava. It was unsalted, but Jimmy ate ravenously from the wooden spoon which Kuria filled time and time again.

"All right, get out now!" snarled Behrens impatiently, prodding the native with the muzzle of his weapon.

Kuria obeyed. Yet the tingle of that magnetic black gaze remained with Jimmy, even when Behrens slammed the door and clicked shut the padlock on the hasp. What in the world could the boatswain have been trying to put across? Merely an expression of his own sympathy and loyalty?

No, Jimmy took that sort of thing for granted. He had always treated his native crews justly and well. They had been respectful, even eager in obeying his slightest commands—and that is an unusual trait in Malays and Lascars.

Jimmy relaxed on his side, his arms one huge ache that crossed his shoulder blades and traversed the small of his back.

Eh! What was that? Under his right hip now was something long and hard. He hunched around, got his fingers on it—and breathed a prayer of thanksgiving. It was a sailor's claspknife, one of the huge affairs that clicks out with a folding hilt, and which cannot be closed except by pressure of a release button.

Kuria had not been able to perform any sleight of hand. The man must have walked into the lazarette, carrying it clasped in his toes!

THE pinpoint isle of Gaba Moa, unnamed even by the few Bugis who once inhabited it—until the tabu lent it importance among Sakita's followers—came in sight just before sundown. On the schooner were Gunong Api and his one remaining rifleman. Rudolph Behrens, half drunk as always, but at his best pitch of efficiency for that reason, strode the deck, keeping in submission the crew of Malays and Lascars whose sullen faces betokened the wrath inside them at what had happened to Jimmy Carlin.

To a man these eight disliked and distrusted Behrens, and he knew it. Against the Bugis, though, if Sakita managed to get home and load a dozen proas with his blowtube warriors, they would fight like slashing fiends. And that was all, beyond the handling of the schooner, that Behrens wanted of them.

Abruptly a disagreement burst forth. Gunong Api doubtless had overlooked the manner in which he was putting himself wholly in the power of his confederate—though it is certain Rudolph Behrens had not slighted that feature. Now the native demurred at going immediately to an anchorage off Gaba Moa.

"Let us proceed for Atee," he urged, scowling as he named one of the island dots over which he held sub-chieftainship, and where he could expect to pick up a bodyguard of followers. "Once we have more men with rifles, then Sakita cannot bother us."

"Yeah?" grinned Behrens. "All in good time. I'm not takin' any, my own self, fella. First off we do things my way—then yours. Once that tabu is stained and busted, even you can't keep me from my chance at that pearl bed!

"Oh, I'll keep the agreement, don't you worry. An' you'll be rid of the white man who threw you overboard." His manner made it plain that he trusted Gunong Api, the renegade, not at all. Which was natural enough, but reduced the latter to a silent, teeth-gnashing fury.

With the Kota Baroe anchored above the virgin pearl beds, Behrens spent the last half hour of daylight scanning the low shore, with its fringe of bent and wind-ravaged palms. King Sakita just possibly might have anticipated his coming.

The little brown ruler might have gathered his subjects hastily and come to dispute any landing on the tabu island of his tribe. However, there was not the slightest sign of life on the deserted place.

"All serene," said Behrens with satisfaction, stowing away his binoculars. "Kuria, you and a couple others come with me. Have others lower the dinghy. Tuan Carlin goes ashore with us—and stays there!" He ended with a chuckle of grim significance. "Got your parang honed good and sharp, Gunong?" he went on after a moment. "I wouldn't want any torture, you know..."

The renegade nodded briefly. He was greenish about his mouth corners, where his lips compressed. The white fool did not understand what this shore trip meant to him, Gunong Api. The killing was good, though that could be done just as well aboard the schooner. But the tabu still held! It was death, supposedly, for Gunong himself to step ashore on the island!

"I shall break the tabu instantly," he reflected, attempting to reassure himself. He shivered, nevertheless, as he put forward this same flimsy argument to his one remaining rifle-armed follower, who showed signs of panic at thought of landing.

Behrens, Kuria, and two Malays came down to the lazarette. The White man scowled when he encountered the burning hatred of Jimmy's glance, but bent down, roughly throwing the supposedly helpless captive to his face, and giving the bonds at wrists, knees and ankles separate yanks.

The cords seemed tight-drawn and-safe. The boatswain, watching, slowly paled to a sickly tan. Jimmy Carlin saw. When he had a moment of opportunity, being lifted, he winked broadly at the native. Whether or not Kuria understood was problematical. The knife, however, was not there on the floor; he could tell that much.

MATTERS came to a swift climax then. Bundling Jimmy into the dinghy, filling it with members of the crew till the gunwales were within inches of the wind-raddled waters of the harbor, Behrens, Gunong Api, and the one rifle carrier rowed toward the island on which it was death to set foot.

Two lanterns furnished all the illumination save for a rash of stars in the blue-black sky; but the white sands of the beach seemed to gather and hold this faint effulgence as a Welsbach filament holds a glow when the gas flame is extinguished. Choppy little waves begun and ended inside the barrier reef, slapped pettishly, their tiny noise a punctuation to the regular whooom-ahhh! of the monsoon surf driven all the way from the Banda Sea.

A quarter mile back of the loaded dinghy quick cries of alarm and a scurrying for weapons sounded aboard the Kota Baroe. Then the Malays and Lascars left behind grew silent, crowding to the rail and watching through the dark, as the menace they glimpsed came abreast and passed them.

Behrens arid the others in the little craft saw nothing, heard nothing but the wind. Death rode that wind which fanned their backs.

Jimmy Carlin waited grimly. The bonds at his wrists had been cut, then rewound. He could free his hands in a hurry; and the opened claspknife was there in back, under the waistband of his trousers. What could one man do against at least three who carried firearms?

While he was being rowed ashore he sensed that this was some horrible rite—more the idea of Behrens than that of Gunong Api. He was meant to die. Before that happened he would take his slimmest of chances, and get at least one of these—Behrens for choice—before they slaughtered him. But he delayed, holding to the forlorn hope that possibly they simply meant to maroon him on this isle, and let King Sakita kill him for breaking the tabu. Quickly that faint hope was banished.

"Bring him here!" commanded Behrens, striding up the beach and indicating with a wave of his hand a broken bole of royal palm, standing like a forlorn and tipsy ghost in the vague quarter-light.

"You come on, Gunong. We'll tie him to that—so's anybody landing will see the scarecrow—a skeleton scarecrow, ha! ha! Ought to give Sakita the willies, all right! How about it, Jimmy? Think you can scare off ail the brownies who come?"

Behrens guffawed again at his heartless jest, and Jimmy's jaw set. This, then, was the end. He gathered himself.

"Look out, Kuria!" he suddenly yelled as the boatswain and another came with Gunong Api to carry him to this impromptu stake.

JIMMY freed his wrists, grabbed the knife—which stuck for one appalling second as the hilt caught under the waistband.

Then he made two downward strokes, slicing through the other bonds: He leaped away, staggering as he felt a lack of control of the numbed members.

A shot crashed. Missed. Jimmy whirled, feeling the singe of burnt powder across his scalp.

Click-clack. Gunong Api was loading again, and his companion with a rifle was jostled as he tried to get into position to fire. Cries came from Kuria and a Lascar, as they leaped upon this second assassin, parangs flashing in the light of the lanterns.

Slash! Kttt! Jimmy cut and stabbed the renegade, who loosed a howl of agony. A howl that ended in a bubbling, sound as Gunong Api slumped forward to writhe on the white sands turning crimson-black under him.

Swearing horribly, Behrens flung up his pistol and fired from a distance of ten paces. Jimmy had seen. He flung himself forward and down, piling atop the body of Gunong Api, and wrenching the loaded Winchester from that death grasp.

In three seconds, momentarily expecting the thudding impact of Rudolph Behrens's second bullet in his back, Jimmy had the weapon and swung about on his knees, ready for his chief enemy.

But something else had come. Scudding swiftly for the shore, their lateen sails full-bellied even as they came at speed for the shore which must damage the frail flying proas, were five loaded outrigger canoes! Coming from the dark, they seemed a larger number, a native navy.

In the prow of the leader stood a short brown figure, leveling a rifle. King Sakita was there to break his own tabu, to stain it before one of his own band set foot on the sands—and thus forfeited his life to superstition.

In the reddish light of the lanterns the stained whites of Rudolph Behrens showed up yellow-red. King Sakita's finger curled and tightened on the trigger, as he aimed carefully at the bulging middle of the white man he hated. Crash!

The proa lifted just as the shot came. But it did not fail in deadliness. With lead smashing through both his temples, Rudolph Behrens pitched forward.

His right hand, closing convulsively for a last time, pumped one more bullet from the automatic. This skipped and dusted along the surface of the beach, dying harmlessly.

Then was the patter of many bare feet in the shallows, as the subjects of the rightful native king came to surround those on the tabu island, and menace them with blowguns and parangs.

SOPHISTRY is a perquisite of sovereigns, so it does not matter much just what explanation Sakita gave his men when the question of killing the rest of these invaders who undoubtedly had broken the sacred tabu.

But there was killing enough, probably, with Behrens and Gunong Api dead, and a prisoner ready for whatever fate Sakita and his counselors decided. And that fate would probably be cruel and terribly gruesome.

The little king strode up to Jimmy Carlin, and touched the back of his hand to his own forehead. Then he did the same thing white-man fashion, extending his tiny palm for a grasp of comradeship which Jimmy was delighted and relieved to return. Jimmy was happy he had reinstated himself with the king. Yes, very happy, indeed.

"The tabu is stained and gone. The blood of an outlander has been shed," said Sakita without visible sorrow. "The agreement cannot be carried out, unless another cares to take up the burden. Someone in whom I can place full confidence and trust. Someone whose word is as good as his bond."

He waited, smiling a little, almost anticipating Jimmie's reply.

"You m-mean—that I might—but I have not—" began Jimmy, stuttering a little when the thrill of Sakita's meaning came to him.

"There is the boat and the stores," said Sakita with a wave of his hand. "I think that there may be a tabu soon—on Tubu-Muna!" he added in his kingly fashion.

"My island!" cried Jimmy, bewildered, hardly able to comprehend the words he was hearing.

"You mistake," said Sakita softly, a faint smile on the corners of his mouth. "This is your island! It may be that by the time you return, there will be a house built for you. And then in after years, when the pearl lagoon has yielded its treasures, there may be coconut palms bearing copra for your presses..."

Jimmy's heart did a handstand of exuberance. Perhaps the matter of his debt to Behrens's heirs might not be adjusted quite as simply as the brown man suggested. Still, something could be done, of a certainty! And of course, as a man of honor, he would see that some proper adjustment would be made to the heirs. There would be no reason for his not doing the fair thing.

"You're a brick, Sakita!" he cried. "Shake again!"

And the little brown king smiled as he complied.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page