RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

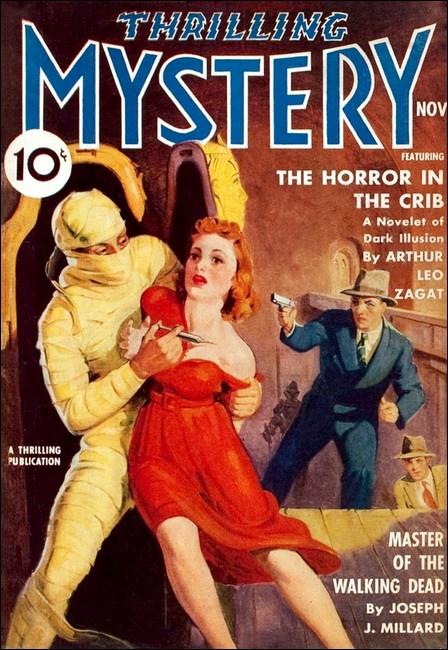

Thrilling Mystery, November 1939, with "The Horror in the Crib"

Neila clawed at the dark swirl of draperies.

Beset by apparitions from beyond, Neila Randall is the

victim of unutterable terror that strikes to the roots of her soul.

NEILA could not sleep. She kept seeing on the screen of her closed lids the gaping dark grave into which she had watched the bronze casket descend that afternoon. She kept hearing the hollow, dreadful thud of the clods that had piled, drab and dank, an eternal blanket over Jim Randall, her husband and lover.

Amos Foster had said that she must try to sleep, that for the sake of Baby Ralph she must get herself back to normalcy. But Neila could not sleep. She could only lie there, thinking of Jim, of Jim's mother and the hate Lucretia Randall bore for her, and the conflict between them that must reach its crisis very soon.

She tried to plan what she would say to the grim old harridan, but her thoughts blurred into panic. She opened her eyes and looked across the dim room to where her son's crib was outlined against the open window's moonlit oblong, and the panic was a little eased.

Neila pushed herself up on her pillow. She could not sleep and she dared not think.

"If you can't sleep, read," Amos had said. "Don't brood."

She reached overhead and switched on the lamp fastened there. Its light was so focused as to be confined to the book she took from the shelf of the night table beside her bed. She adjusted the dark glasses Amos had brought her to wear at the funeral, so that she might hide her tear-reddened eyes from curious glances, one more reminder of the kindly old lawyer's thoughtfulness.

The print ran together on the page, an undecipherable blur. "Neila!" her name came out of the gloom. "Neila!" It was Jim's voice that called her name, as if from a limitless distance! "Neila!" It was loud now! It was in the room! "The baby! Quick, Neila. The baby!"

She was out of the bed and across the room. Her hands clutched the crib's top bar and her eyes stared down into it. Her slim body was sheathed with ice and a scream ripped from her throat.

Tiny reptilian eyes blinked up at her from the beribboned pillow, hooded eyes in a green, grotesque head that was long and flat and triangular, a head split by a fang-serried, malignant grin. A crocodile!

"Kill it!" Jim's voice husked in her ears. "Neila! Kill it!"

With what? The mother whipped about, looked frantically for a weapon, caught a gleam of metal on the dresser. She darted to it, snatched up the long, keen shears, whirled again, started back. Her feet caught in the silk hem of her nightgown and she fell headlong. Her hands thrust at the floor. She lifted, heard the bedroom door opening behind her as she sprang to the crib. Fingers grabbed her arm, bruising fingers. A frightened little cry came from the crib.

Baby Ralph was looking up at her, the corners of his blue eyes crinkling with recognition, his chubby little hands waving!

"Neila Randall, what on earth are you doing?"

Neila twisted, stared into the face of the woman whose dry voice had asked that. It was Lucretia Randall. Jim's mother was stiff-backed, dour even in her old-fashioned flannel nightgown. "What's the matter with you?" she demanded.

Priscilla Slade, Lucretia's aged companion, picked up Neila's glasses for her. "Looked like she was going to stab her baby with those shears," the wizened woman cackled.

Not her baby, the—But she couldn't tell them about the crocodile; they would think her mad.

"What an awful thing to say!" she exclaimed, turning back to the crib and reaching into it. "I was cutting off this torn binding from Baby's blanket." She felt only the warm infant's body, nothing else. "Look." She held up the blanket for them to see.

"But you screamed," said the grandmother, disbelief in the chilled, steel-gray of her eyes. "We heard you scream, and came running."

There was nothing in the crib, nothing on the floor, anywhere in the room. The window was screened so that nothing could possibly have got out through it. Impossible that little Ralph would be crowing so happily if the—thing actually had been in there with him. Neila made her face expressionless.

"Did I scream?" she asked dully. "Perhaps I did. I had a nightmare and I may have screamed in my sleep. It woke me and I remembered about the torn binding—" She turned away from them, cuddling her eight-month-old son.

He reached his little hands up to her face, gurgling happily, unaware that he would never know a father's care, a father's love. "Hungry, honey?" Neila cooed. "Mother will fix your bottle—"

"It isn't time yet for his feeding," Lucretia objected.

"He's getting one right now," Neila replied through lips abruptly tight, "Mrs. Randall." Calling the woman "Mother" had always annoyed her, and now there was no longer any need for it, no longer any need for Jim's sake, to veil the antagonism that lay between them. "I shall take care of my baby in my own way, whether you like it or not."

Prissie snorted. "The impu—"

"Quiet, Priscilla," her mistress snapped. "Let me handle this." And then, "Neila Randall, I will not permit you to speak to me in that manner in my own house."

"It may be your house," Neila said passionately, "but this is my room. I ask you to remember that I am entitled to its privacy as long as I remain here." She gulped, decided to say now what she had intended to wait to say till Lucretia's first grief had dulled. "That won't be for long. I have lived here with you for two years because I did not wish to make it impossible for Jim to be both a devoted son to you and a loyal husband to me. Now that he is gone, I am released. Ralph and I shall move out as soon as I can make arrangements."

Hate made a gray and twitching mask of the old woman's face. "You cannot leave soon enough to suit me," she said thinly. "But the child will remain. If you think that I will allow my grandson to be brought up by a common drab from the slums—"

"Get out!" Neila's command was low-toned, but there was a virulence in it, a pent fury that silenced Lucretia Randall and drove her back, step by unwilling step, across the moon-silvered floor to the open door and out through it. Her wizened companion retreated with her, but paused in the doorway, her sharp-featured profile parrotlike.

"You're a fool, young lady," Prissie cackled, "if you think she'll ever let you take the baby away from her. She's always got everything she wanted. She'll find a way to get that, too."

The door closed, and Neila was alone. All her control fled. Shudders ran through her girlish frame. Jim Randall, jaded and seeking some new thrill in the teeming East Side slum street, had spied her trudging home from work and won her heart at once with his flashing, boyish smile. Her teeth chattered. Her knees buckled so that she had to hold on to the crib to keep from sliding to the floor.

She had not dreamed what had happened here moments ago. She'd been awake, fully awake. But it could not have happened. It was beyond all reason that Jim had called to her from the grave, that a green-scaled monster had taken the baby's place.

Neila moaned. The terror which squeezed her heart was of a different kind now, different and worse. People who had hallucinations were mad!

A thin cry came from the crib. "Yes, honey," Neila cooed. "Yes, my love. Mother's getting your bottle."

The warm, confiding little body in her arms, her lips on the satin skin of Ralph's cheek, Neila Randall sat through the long night, staring into the dreadful shadows.

"She won't take you from me." Dawn's chill gray was stealing into the room when Neila's cold lips whispered that. "Never. I won't let her."

"NO, my dear," Amos Foster said the next evening. "I haven't done anything about finding other quarters for you." His corpulent form filled the armchair in the little sitting room that opened from the bedchamber. "I wanted to talk over your decision first." He smiled, his bright eyes kindly in the light of the single table lamp, his sparse hair gray at the temples. "Now that you've had time to become more nearly normal."

"Normal?" Neila caught up the word. "What do you mean?"

The lawyer's pudgy hand made a deprecating gesture. "It wouldn't be natural if Jim's terrible accident, the shock of his sudden death, had left you able to see things straight."

No, Neila thought, it wouldn't be natural.

"Neila," Foster's voice was low and persuasive. "I am more than twice your age. I was Jim's father's friend before you were born, and since Henry Randall's death, I have been trustee of his estate. Surely, I should know Lucretia better than you. Won't you listen to me when I tell you that her hardness is all on the surface, that beneath it there is as warm and affectionate a woman as any in the world? Won't you let me plead with you to give that real Lucretia Randall a chance? It would be cruel to take her grandson from her, to cut her off from the last one in the world left to her to love."

"Cruel!" Neila paced the floor, slapping her arm against her side. "Not as cruel as she has been to me, using her power over Jim to keep us here in her house. Making me feel like an interloper, a—a thief. She doesn't want me here. She hates me as only a woman can hate another woman. It's only the baby she wants. But she can't have him. She can't have him, I tell you—" A sob choked her.

"You're hysterical, Neila—"

Darkness smashed into the room, cutting off the lawyer's words. The girl whirled to the lamp.

A fleshless skull grinned at her from out of a bluish, man-form glow! It topped a bony skeleton that moved toward her, its bony fingers reaching out to clutch her, its curving ribs plain against the pale oblong of the window.

"Not hysterical, Neila." Horribly, there were some of the intonations of Jim's voice in those rasping accents. "Insane, Neila. Mad!"

AND then there was light in the room again, light of the lamp on the table beside which Amos Foster had been sitting. He was on his feet, fumbling at the lamp.

"The bulb must have come loose," he said, turning to Neila. "I tightened—What's the matter, child? Are you ill?"

Neila stared at him, her pupils dilated, her lips writhing.

"You look like you've seen a ghost," he said.

"I have," the girl contrived to whisper. "I saw Jim, already a death's head. I heard him—"

The lawyer's hand was on her arm. "Child!" he exclaimed anxiously. "What are you saying?"

"Didn't you see him?" Her voice was thin and strained, frightened. "Didn't you hear him?" she gasped.

"Of course not!" Foster's fingers were under her chin, were bringing her eyes up to meet his. "Listen, Neila. Listen to me. You're still overwrought, and I understand. I had no right to upset you as I have, and I won't do it again. But I've got to tell you this. I've got to warn you. You must not say anything like this to anyone else. You must not! Do you understand?"

"No," Neila whimpered. "I don't understand, Amos. Why shouldn't I?"

"Because if you do, you will give your mother-in-law the pretext she needs to take your baby from you, and in her present mood, she will use it. With witnesses to any story like that, she could have you declared—"

"Insane," Neila gasped, her shudders abruptly stilled. "Crazy!"

"Exactly," Foster shrugged. "And then—"

"She could take Ralph away from me. But I'm not insane, Amos—"

"Of course you're not, my dear. You're just overwrought, and that's where the danger lies. Take the advice of one who wishes you well, of one old enough to be your father. Go to bed right now, even if it is very early. Get a good night's sleep, a good rest. You will be surprised how much that will do for you. By tomorrow evening, you will be able to think clearly and composedly, and I'll come back then to talk all this over with you. Good night, Neila."

He went out and she went slowly into the bedroom of the little suite that for two years had been her only sanctuary from Lucretia Randall's hating eyes. She glimpsed movement out of the corner of her eyes, whirled to it. Amos Foster was right, her nerves were at the breaking point. What had startled her had been merely her own reflection in the great mirror that formed the whole inner surface of the door to the corridor.

She went to this. The lunar luminance filtering in through the open window, gave light enough for her to see herself. Her tousled hair made a tawny frame for the pallid oval of her face. Her cheeks were sunken, her lips quivering. Blue shadows lived under her hazel eyes, and in those eyes crawled the little light worms of a terrible fear.

Neila turned away, undressed, drew on the misty chiffon of her night-robe, slid her icy feet into the frivolously pompomed mules that once had so amused Jim. She went into the bathroom. After a while she returned, carrying a large box of perfumed bath powder. Taking the cover from this, she blew across the surface of its contents, walking about the chamber as she did so.

The air filled with the fragrant dust. It settled slowly, but when Neila had finished, and was sitting on the edge of her bed, an unbroken film of the fine powder covered the floor from wall to wall.

She kicked off her mules, slid under the sheets, adjusted the pillows so that they would support her, half sitting, half reclining. She could see the door from the hall, the door into the sitting room and the window above little Ralph's crib. Wide-eyed, she waited.

The moonlight slid slowly across the floor, the shadows retreating from it. The silver radiance on the white dust was eerie at first, but when Neila became accustomed to it, it was dreamlike. Lovely. The whisper of the baby's breathing was soft, soporific. This room was at the rear side of the house, and there were no near street sounds to disturb the gathering silence. Sleep tugged at Neila's lids.

She must not let herself sleep. Dared not. She reached out to a small radio on the night table beside the bed, adjusted its volume knob to almost the lowest notch, clicked on the switch. The lighted disk with its black markings seemed friendly. In an instant, it would give her music to keep her awake, swing music, lilting and merry.

Not music, but speech tuned down to the merest whisper of sound, came into the room. "Once more it is seven-forty-five. Once more it is our privilege to bring you Zingar for a quarter-hour of Weird Wisdom—" Neila's hand went out to switch that program off, to tune to another station—and froze on the knurled knob.

The door to the corridor had vanished! There was only blank wall where it had been, and out of this blank wall was growing a thing of dread. The shape was entirely cloaked by dark draperies, but somehow its outline came through these, a form of pure, heart-stopping horror, loathsome and evil.

It detached itself from the wall. Soundless and stealthily, it drifted across the room toward the baby's crib. As it passed her bed, an odor reached Neila's nostrils, fetid, as if from some opened sepulcher.

Neila could not move, could not cry out. The Thing seemed to be peering into the crib. Its draperies undulated, and Neila perceived that it was about to reach down for Ralph. That brought her out of her bed, rasping a wordless protest. She rushed to the defense of her child.

The Shape turned, its dark veils outspread like the wings of some gigantic bat. "You have no right to him," Jim Randall's voice husked. "You must give him up."

"Never!" Neila cried, clawing at the dark swirl of draperies. They enveloped her and she fell—down and down into a Stygian abyss, down into a bottomless chasm.

Abruptly the blinding veil was gone. Neila was sprawled on the floor, and the dark, incredible Shape had vanished. She pushed up on her hands, saw that the corridor door again broke the wall, as it always had. She came erect, twisting. Little Ralph, untouched, unharmed, lay peacefully asleep in his crib. Neila turned again.

The dust film on the floor was no longer unmarred. There were the marks of her feet on it as she had dashed from the bed, the mark of her body where it had sprawled. And there were other markings.

They came across from the corridor door, and they went back to that door. They were blurred, but they were formed like no man's, or woman's, feet were ever shaped!

Her plan had succeeded. Terribly! There, in those markings on the floor was proof that what had come into this room was not a figment of her disordered brain, indisputable proof that what had leaned over her baby's crib was something physical, something that had materialized from beyond the curtain that divides the known from the unknowable. This, and the skeleton and the saurian monster all were real, though they were manifest only to her.

"There is no Outer World of Darkness," a voice intoned, low but deep-chested and hollow, and edged with a peculiar huskiness. "No ghost, no elemental, no apparently supernatural manifestation, has ever appeared or ever will appear except through the operation—accidental, willful or malicious—of the laws of nature and of science." The statement, so pat to the spinning, terrified chaos in Neila Randall's brain, came from the radio that all this time had remained on. "This is my message, and if its truth be challenged, I will go any place, at any time, to meet that challenge."

There was an instant of rasping silence, during which Neila did not move, and then the cool, professional tones of a network announcer were saying, "With his now famous defiance, Zingar concludes his twenty-ninth broadcast. If any of you wish to dispute the assertion he has just made, or desire his help, you may communicate with him in writing addressed to this station or, if the matter is urgent, by telephone directly to Zingar's studio, from which this broadcast originated. The number is Academy, seven-nine-four-hundred. Zingar's Weird Wisdom will be heard again at—"

Neila Randall managed to switch off that radio. Somehow, her left hand was grasping the base of the telephone that stood on the night-table beside it, and the forefinger of her right hand was twirling its dial. A . . C . . 7 . . 9 . . 4 . . 0 . . 0.

ZINGAR'S hand, white and slender, each finger seemingly imbued with a separate life of its own, set the microphone into which he had been talking down on the floor beside the divan on which he was outstretched. He lay wearily back among the cushions piled on the divan, his eyes glowing like sombre coals in their deep sockets.

Zingar's body was very thin and very long. It was clad, as always, in a lusterless black suit so fashioned with the vest high and squarely cut at the top as to be almost clerical. Zingar's face was narrow. The skin was tightly drawn over the high forehead, the knife-bridged nose and sharp chin were dead white. His hair was a smooth skullcap as lusterless and black as his suit.

Theatrically as Zingar was clad, theatrical as was the great, high-ceiled room with its curtained walls, its trappings of skulls and naked swords and crystal globes, stagey though the flaming brazier that was its only illumination, there was something more than the melodramatic about him. A discomforting sense of the uncanny that was very real, an inescapable feel of inner power that transcended mundane things. As familiar as Richard Wayne, his friend and assistant, was with his tricks of manner and costume and voice, as well as Wayne knew these to be false as the tricks of magic for which Zingar was famous, he could never rid himself of this spine-prickling awareness.

"You are exhausted tonight, Zingar," Wayne said from a deep-seated chair far across the room. "You've been going it too strong. If you don't rest—"

A soft buzzing interrupted him. He reached out to a marble model of the Temple of Astaris at Pilae that stood on a platform beside him, opened its ornate bronze portal and extracted from it—a telephone! The buzzing ended as he plucked the receiver from its cradle.

"Hello," he said. "Zingar's assistant speaking. What is it?"

Wayne himself seemed as much out of place in these occult environs as the instrument itself. Sturdy, well set-up, blond-haired, blue-eyed and blunt of jaw, he might have been a football hero or a bond salesman, or anything at all rather than Achates to the foremost stage magician of the time. The lines of his broadly molded countenance hardened while he listened.

On the divan, Zingar's lids closed.

The voice in the telephone ended its long tale of a dead voice speaking, of manifestations beyond the pale of human experience.

"I quite understand how perturbed you must be," Wayne said soothingly. "But I'm sorry, I cannot disturb Zingar tonight. He has just gone to sleep, and if I were to awaken him, he would be ill. I shall tell him about your case in the morning and will let you know if it interests him... No, I am very sorry but I dare not... In the morning, I promise, I'll tell him, but that's the best I can do for you."

He put the phone back into its hiding place.

"All right, Richard," Zingar said. "Get busy looking up Jim Randall and his mother. That ought to be easy, they're a Social Register family, and I recall that Jim hit the high spots before he married. Our newspaper files and other usual contacts ought to give you all we'll need to get at the bottom of this thing. It shouldn't take you more than a half-hour to get the information, and the Randall house isn't more than ten minutes from here. We can get on the job there by nine."

Wayne's jaw dropped. "How—how do you know—"

"No questions, Richard." The corners of Zingar's thin lips twitched in what might have been a smile. "That is our agreement, if you recall." There was no harm in impressing Wayne with his idol's omniscience. There was no need to tell him of the induction coil that, without any material connection to the telephone, had brought to the diaphragm hidden in the cushion on which the magician's head lay every word of Neila Randall's detailed story, of her desperate plea for help.

THE powder film on the rug and floor in Neila Randall's bedroom was marked now by many zigzagging lines of footprints. Back and forth, back and forth she prowled, a mother distraught, a tigress whose whelp was threatened by a peril she did not comprehend, a woman terrified.

Fifty times she had gone to the door to call to Lucretia Randall. Fifty times recollection of Amos Foster's warning had checked the cry in her throat. Who, hearing what she had to tell, would believe it? What alienist would not say at once that she was driven insane by grief? What court would not declare her unfit to take care of her babe, send her to some madhouse and give control over Ralph to his grandmother?

But Neila Randall knew she was not insane. Some eerie menace overhung her, overhung her tiny son. Alone, she could not continue much longer to fight that threat from beyond the veil, and in all the world there was no one she could call upon to help her fight it.

Once more she had gone to the phone, to call Amos Foster, and as her hand touched the instrument, she had realized that not even to him, who was her only friend, dared she speak out. He would not, could not, again dismiss her assertions lightly. Not in conscience could even he justify himself in leaving an infant in charge of a mother who saw, and heard, the things she had seen and heard. He would insist on investigating, on asking questions of the household. Lucretia would tell him of finding Neila bending over Ralph's crib with a sharp-pointed shears in her hand, evidently about to stab the child. He would turn harshly against her.

As for Zingar—"Tomorrow," his assistant had said. "In the morning." The hands of the little clock on Neila's dresser pointed to five after nine. The morning was ten hours away. In those hours what might not happen, here in this room, to her and to Ralph? What crowning horror—

Neila whirled to a rap on the hall door. Her mouth opened and she was a rigid statue of terror staring at it, her heart stilled in the clutch of a gelid hand. The rap came again and a voice through it.

"Mrs. Randall. Mrs. Randall."

Held breath gushed from between Neila's white lips. It was only Hawkins who had rapped, the Randall's aged butler. "Mrs. Randall," he called again, rapping imperatively.

"Just a minute," the girl answered, snatching a filmy negligee out of a closet, slipping into it as she slid her feet into her discarded mules. Then she was at the door.

"I was in bed," she said. "What is it, Hawkins?"

The wizened old man in livery blinked at her, his pale eyes watering. "Beg your pardon, madam, but there is a gentleman here to see you, sent by Mr. Foster. He intimates that it is important that he speak with you immediately."

God bless Amos! He had sensed that she needed help, had sent someone. But who? Why had he not come himself?

"Show him into my sitting room, Hawkins. I will join him there as soon as I make myself presentable."

Trembling, Neila closed the door to the other room, darted to her dresser. She ran a comb through her tangled mop of tawny hair, deftly applied rouge and powder to her pallid cheeks. Lipstick hid the grayness of her lips. Back at the sitting room door, she hesitated an instant, gathering her reserves, went through, leaving it open so that she would not for a moment be cut off from Ralph.

The man standing by the window and peering out was tall, spare to gauntness. Hearing her enter, he turned, and Neila saw a narrow face that seemed all sharpness, pointed nose, pointed chin, black, piercing eyes. The voluminous folds of a sleeveless black cloak hung about him.

"Good evening?" she faltered questioningly.

"Good evening, Mrs. Randall." There was something familiar about his tones, deeply resonant and edged with a strange huskiness. "I am Doctor Anthony. Your friend, Mr. Amos Foster, suggested that I might be of aid to you."

"Amos—" Neila gulped. The old lawyer had not taken what she had said as lightly as he had pretended. "But I am not ill." Why had he sent a doctor without consulting her? Why had he not come himself? "I—" she managed a laugh—"I am quite healthy."

Doctor Anthony did not smile. "I am not a physician of the body," he responded. "My province is the mind."

The mind! No, Amos hadn't taken her lightly at all. He thought she was going insane.

"It is better that you willingly unburden yourself to one who is friendly disposed," the physician continued, "than be compelled to speak out to another who may be influenced in his judgment by—er—obligation to an employer." Those black eyes of his were on hers and they seemed to be boring into her brain, to be dissecting her soul. "Mrs. Randall, you were not frank with Amos Foster. The strange incident that occurred while he was in this room is not the only one of the same nature that has appalled you. There was one before, and there has been one since—"

The girl gasped. "How do you know?"

"I read it on the screen of your mind. I read horror there, and fear, and the cry for help you dare not utter. I can help you." Anthony's voice had a lift in it now, a certainty that lent assurance to Neila, that gave her hope. "But only if you have confidence in me. Full confidence, no matter what I may say or do. Do you trust me, Neila Randall?"

"I trust you," Neila whispered, but it was as if someone other than she were speaking. "I have confidence in you, Dr. Anthony."

"Very well," the strange man said. "Take me into the other room. Show me the door that became a blank wall out of which grew a Thing that left footmarks in the dust with which you powdered the floor. Show me the crib in which your son was metamorphosed into a saurian, and then back into a babe. Show me these things and tell me exactly how they appeared to you, and then I shall be able to help you."

"Come," Neila breathed.

His tread was curiously silent as he followed her into the bedroom. She reached for the switch in the doorjamb. His hand caught her wrist and his fingers were cold on her skin, as cold as though there were no blood in them.

"No. I want everything to be as it was when you heard your dead husband's voice and saw the manifestations that so terrified you."

He went noiselessly across to the mirrored door, touched the knob. Now he was prowling back toward her bed. He paused at the little night table next to it, picked up the glasses Prissie Slade had put down there, lifted them to his eyes. The pale green lenses seemed to merge into the odd pallor of his skin, to become empty sockets in his skull.

Anthony put down the glasses again, was moving toward the crib. His long, black cloak billowed about him, undulated. The marks of his feet on the powdered floor were blurred and shapeless! He reached the crib and bent over it. His cloak billowed out as he reached down to the sleeping infant, and its black swirl was like the outspread wings of some gigantic bat!

Neila's breath was an icy bubble caught between frozen lips! This was no physician! This was the—

"Hands up!" a hoarse voice commanded. "Hands up or I'll shoot!"

Neila's head jerked to it. Old Hawkins was in the doorway from the sitting room, a blunderbuss of a revolver in his palsied hand. Behind Hawkins were Lucretia Randall's twitching face and the colorless, parrotlike visage of Priscilla Slade.

"You dare not fire," Dr. Anthony said quietly. He had straightened and he was holding little Ralph in front of him, the blanket-wrapped babe a shield. "Not unless you are more expert a shot than I think you are." His free arm was behind him, and from her vantage point Neila could see its long white fingers writhing curiously, as though each had a separate, evil life of its own.

There was a little flurry in the doorway, and Amos Foster pushed through, livid with rage.

"I don't know this man," he snapped. "I never saw him before—"

A scream shrilled through his words, Lucretia Randall's scream. Her shaking finger was pointing at the infant—at a tiny squirming skeleton denuded of flesh, that was in the crook of Dr. Anthony's arm!

"Ralph!" Neila cried. "My baby!"—and sprang to the infant, mother-love striking terror from her, striking fear from her. She clutched the wee skeleton, snatched it from the man's hold, sprang away. A frightened little cry dragged her eyes down to that which she held. It was Ralph, little Ralph, his blue eyes frightened, his rosebud lips opening to vent another yell.

The group in the doorway was disrupted. Lucretia Randall fell to the floor in a dead faint. Priscilla was going down after her. Hawkins had reeled against the doorjamb, gray-faced and pop-eyed. Foster snatched the revolver from his lax hand. "You fiend," he yelled. "You fiend from Hell!" The gun jerked up.

Anthony leaped, jabbed a stiff forefinger expertly into Foster's neck. The lawyer stiffened, paralyzed by the jolt on a certain nerve ganglion. Anthony caught the revolver dropping from his numbed fingers, swung to Neila.

"It's all right, my dear," came his amazing reassurance. "You're safe now and your baby is safe. I told you that if you trusted me, I would help you." He turned back to Foster. "She's quite safe now, Amos, isn't she?"

"Safe?" the lawyer mouthed, staring at the black-cloaked man whose white fingers held the revolver so that it seemed to cover no one and everyone. "What—what do you mean? Who are you?"

ANTHONY was looking at the two women on the floor. They were stirring. They were sitting up.

"Who am I?" he said softly. "Why don't you tell your clients who I am, Amos Foster?"

"I never saw you before."

"Perhaps not. But I am sure you have heard me. Remember? 'There is no Outer World of Darkness,'" he intoned, his voice deep-chested and hollow and edged with a peculiar huskiness. "Surely you have heard me, Lucretia Randall and you, butler. 'This is my message and if its truth be challenged I will go any place, at any time, to meet that challenge.'"

"Zingar!" Priscilla Slade gasped. "He's Zingar!"

The tall man nodded. "I am Zingar," he agreed, "and I am here because I was challenged." His eyes were bleak now, and deadly, but like his gun, they seemed to rest on no one and on everyone. "By a schemer as ingenious and as darkly evil as any I have been called upon to thwart."

"What—" Foster sputtered. "What in the name of all that's holy—"

"Nothing holy about it. Dark things have come to pass here, and malice gave them life, or greed. Do you know which?"

"I? How should I know?"

"Do you, Lucretia Randall?"

The old woman had risen. "I don't know what you are talking about," she snapped. "And furthermore, I am not interested in the tricks of a mountebank. Hawkins! Please show this man to the door."

"Wait, Hawkins," Zingar said, and there was the faintest shadow of a smile on his thin lips. "I shall have to impose on your mistress' patience a moment or two longer. Mrs. Randall, attend me. It is true, is it not, that your husband's will left his estate in trust, its income to provide for you for life and for your son James until James married? When the young man did so, the trust estate set aside for him was to cease, and the principal to become his to do with as he pleased. Correct?"

"Yes, but—"

"Influenced by you, James Randall did not claim his inheritance when he married, but left it in the hands of the previous trustee to manage. Then Jim died, and his wife determined to leave your house, and requested a settlement of the estate.

"This had to be avoided, and it could be avoided only if Neila Randall also died, or if she were adjudged insane and her child's grandmother appointed his legal guardian. If she were adjudged insane, Mrs. Randall, because of certain wildly incredible tales she told! Because of hallucinations she had, and her apparent attempt to murder her babe, and—"

"Hallucinations?" Lucretia broke in. "What hallucinations?"

"Don't you know?" That piercing gaze of Zingar's was on her gray eyes. "Are you certain you don't?"

"The man's insane," Prissie Slade blurted indignantly. "He's clean, raving mad."

"Perhaps," Zingar sighed. "But not too mad yet to read the truth in a woman's eyes. So it was you alone, Amos Foster."

"Yes," the lawyer said thickly. He was holding on to the doorpost with both hands, as though suddenly his legs were too weak to support him. "I—" He broke off and averted his face.

Zingar took up the conversation. "You were consistently stealing from the principal of the Randall estate, of which you have been the trustee for years. Lucretia Randall and her son trusted you, and you had nothing to fear, since they never asked for an accounting as long as you supplied them with enough money for their needs. You had some bad moments when Jim married, but you cleverly stirred Lucretia Randall up against the fine young woman who was changing her son from a wastrel to a real man, and she insisted on Jim's living here. As long as he did so, you would continue to handle his share of the estate.

"But your scheme boomeranged against you. James Randall was accidentally killed, and you had made it impossible for Neila to live on here. She told you she was getting out, requested you to arrange to hand over her inheritance. You were caught in a trap, and you tried to find a way out by fooling her into acting as though she were insane. If she were committed—"

"Fooling me!" Neila exclaimed. "But I saw those things. We all saw Ralph turn into a skeleton just now. And I saw a skeleton in that sitting room, Jim's skeleton—"

"Not Jim's, Neila," Zingar corrected. "Foster's."

"What!"

"Yes. There is a vacant house across the areaway outside these windows, a house that belongs to the Randall estate. Foster installed an X-ray machine in there, its beam focused through the sitting room window. When he called on you, earlier this evening, he wore clothing saturated with fluorescent salts, had painted his face and hands with a solution of the same. He was between you and the window when he turned out the lamp, and since he had to all intents and purposes made himself into a fluoroscope, you saw his skull and his bones as you would on a fluoroscope's screen."

"But my baby? He didn't paint Ralph—"

"No. But when I bent over his crib, I wrapped him, head and all, in a sheet similarly prepared that I'd brought with me, and when our friends burst in on us, I dropped the blanket. I signaled behind my back to my assistant, who remained in that other house while I came to this one. He switched on the X-ray machine and, presto, little Ralph was a skeleton. By the way, Hawkins, how did it happen that Foster came in on us this way?"

"Mr. Foster returned to the house, sir, claiming he had left his cane. I remarked to him that his friend, meaning you, was here, and he got excited. He said you must be a kidnapper after the child. So I grabbed a gun and came running up, Mrs. Randall and Priscilla following me—"

"Zingar," Neila interrupted. "You haven't explained the Shape that came into this room. X-rays don't leave footprints."

"Nor do doors vanish. That, my dear, is the oldest stunt of stage magicians. Look." He walked across to the entrance from the hall. "Move over, all of you, to the head of Neila's bed. You are on the hinge side of this door and it is a mirror. Now watch." He opened the door, swung it into the room until it made a forty-five degree angle with its threshold—and disappeared!

"You see?" Zingar smiled. "The mirror has brought the reflection of the wall at right angles to the one in which it is set, into the plane of the first one and thus, in the dim light, it seems to fill the empty space. Foster, swathed in black, came around its edge and appeared to materialize out of nothingness.

"Most of this I got out of your story over the telephone, but the first illusion, the one in which your baby appeared to have been changed into a crocodile puzzled me. It wasn't till I saw those glasses on your night-table that I understood the mechanics of that."

Neila stared. "The glasses! But they're ordinary tinted lenses—"

"They are not! They are made of a special material that passes only those light vibrations that occur in a certain plane. Ordinary light vibrates in all planes, and so you can see an object illuminated by it through these lenses, but it will be somewhat dimmed, and when it is a pale light by which you see it, will practically be blotted out. So, if a strong beam of light that has been polarized to match the polarization of the lenses throws an image on such an object, the real object will seem to disappear and the image to take its place.

"Foster had arranged a projector of such a beam of polarized light in that interesting window of the house across the areaway, and with it threw the picture of a crocodile's head on the head of your baby, that was illuminated only by pallid moonlight. That image, seen through your glasses, was so strong that it altogether obscured Ralph's little head. Your dead husband's voice, simulated by Foster and projected into this room by a loudspeaker, completed the illusion of the supernatural.

"He watched you through the window, and when he saw you strew powder on the floor, saw a chance to work another deception. He probably has a key to this house. How do I know all this? Because my assistant and I checked everybody and everything before I came here. We had already found the equipment next door—"

The sound of a falling body interrupted him.

"Mr. Zingar!" Hawkins exclaimed. "There's something the matter!" The butler was on his knees beside the sprawled, still form of the lawyer. "He's—he's dead," the butler whispered. "I saw him fall, he's dead."

"Yes," Zingar sighed. "When he saw the baby turn into a skeleton, he knew that his device had been discovered. He tried to kill me and failed. When I started to expose him, he put his hand to his mouth in confession of defeat. He might have brazened it out, but he was a ruined man and he chose this way of escape."

Zingar turned to Jim's mother. "Mrs. Randall, you fainted, horror-stricken at a tithe of what Neila has seen and heard and fought alone. Does not that make you realize the strength of character, the maternal devotion she manifested for the sake of her son? Of your grandson? Do you think, now, that she is fit to be his mother?"

Tears wet the wrinkled face that had remained dry over a dead son's coffin. "I do," Lucretia Randall sobbed. "I do, indeed! Neila, can you forgive me? Can you ever forgive me?"

There were tears in Neila's eyes, too. "Forgive you? Amos Foster deceived me; why cannot I forgive you because he deceived you? Of course, I forgive you—Mother."

"Daughter!" A look of unbelieving joy transformed the old woman's countenance.

And then they were in each other's arms, the crowing little babe between them, separating them and yet binding them together.

"But I must thank Zingar," Neila exclaimed at last, pulling away. "I—Oh, he's gone!"

"Yes, madam," Hawkins said dryly. "He requested me to inform you that he is superstitious about being in the same house with a suicide."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.