RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Charles Gilson (1878-1943)

"The Lost City,"

"The Boy's Own Paper" Office, London, 1923

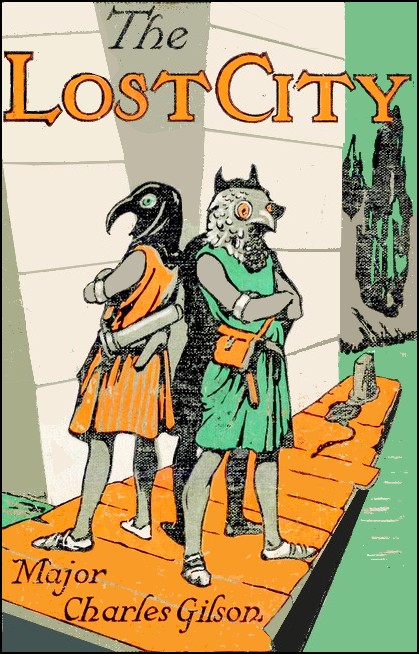

Title Page of "The Lost City"

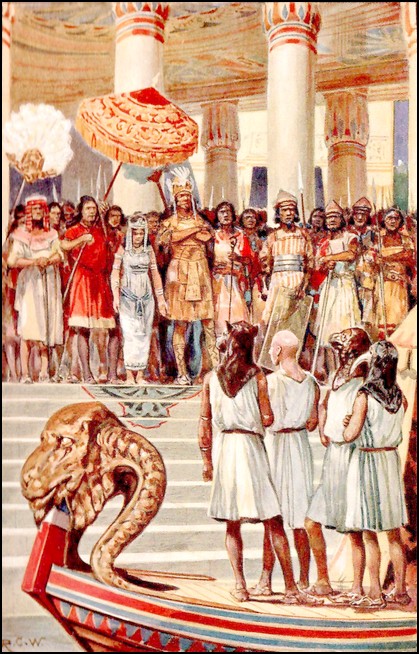

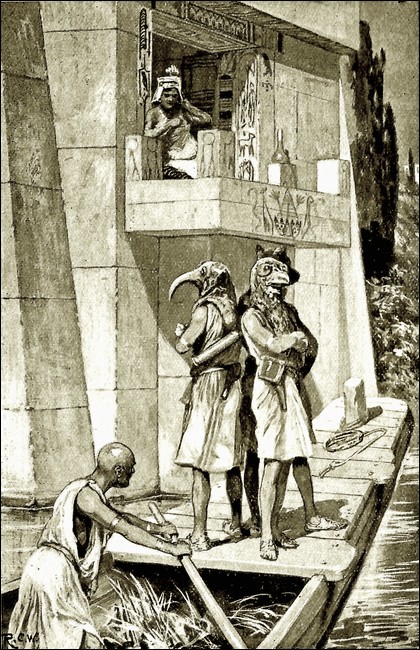

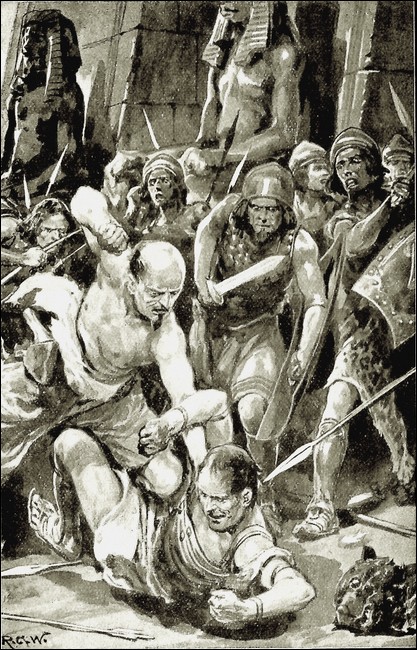

Frontispiece.

One glance was enough to assure me that this was Serisis,

Queen of the Serophians, the descendant of the Pharaohs.

HAD I been informed, a few years ago, that I, Miles Bowater Unthank, Professor of Ancient History, should append my name to a volume of travel and adventure—which, moreover, has every aspect of a work of fiction—I should never have believed it. Neither should I have thought it possible that I should be called upon to stake my reputation for truth and accuracy by appealing to the common credulity of the public, whom I ask to accept as the truth a series of remarkable occurrences which have every appearance of the supernatural.

Steeped as I am in Egyptian lore, familiar with the strange religious rites and occultism of that wonderful civilisation of the past, I am in no sense a believer in the mystic. I would ask the reader to believe what I myself believe: namely, that the scarabaeus itself exerted no direct, or indirect, influence upon any one of us. Indeed, it is ridiculous to suppose that a mere piece of stone, a few ounces of green jasper, could in any way affect the lives or control the destinies of simple human beings. I myself consider everything that follows a singular example of coincidence. Let the reader think as he chooses.

I am, by natural inclination, a man of peace, a student and a scholar. My researches have taken me frequently to the Nile, on three occasions to Mesopotamia, and once upon a journey of some duration throughout the Holy Land and Greece. I have never had the least desire in the world to face danger in any shape or form; indeed—since I desire to be understood from the very first—I admit with honesty I regard myself as a coward.

I have no skill in the use of arms. My physical strength is inconsiderable; and when I explain that I am no more than five feet four in height, and weigh barely eight stone six, this will be readily believed. For all that, I am of opinion that the remarkable story that follows requires something in the nature of an introductory autobiographical note.

In certain circles I am, I suppose, a well-known man. The vast majority of people, however—especially those who are likely to read this narrative—are quite unacquainted with my name. I have no hesitation, therefore, in explaining briefly who I am, since I take no credit for having taken part in the adventures that befell my comrades and myself in our search for the sarcophagus. No credit is due to me. I drifted into the matter quite unaware of whither I was going, and when I found myself encompassed by dangers, beset by hardships, cast for the role of an explorer and adventurer, I speak nothing but the truth when I say that, at the time, I devoutly wished that I was out of it.

None the less, I fail to find words to express the boundless admiration I feel for the two extraordinary and heroic men who accompanied me throughout many of those troublous days. To each of them I owe my life; to each of them I owe a debt which I shall never be able to repay. Captain Crouch is a man for whom I shall always have a most profound respect. His fiery courage, his presence of mind that never deserted him, even in the most perilous situations, his optimism and his honesty—these were the qualities that make me proud to remember him as a friend. As for Mr. Wang, I may be neither man of the world nor student of human nature, but I never saw his like for quickness of decision. His powers of deduction were almost superhuman. In the course of our wanderings, I was accorded many an opportunity of observing the workings of his imagination, the logic of his intellect. He was as brave as Crouch, and in spite of his stoutness, almost as insensible to fatigue. It was, indeed, a singular stroke of fortune that threw them in my way at the very outset of the mystery; and I tremble to think what would have become of me, had I not obtained their assistance and advice. Of a certainty, I should have perished miserably in the heart of the Nubian desert, and long since my bones had been picked dry by the vultures and the kites.

For Providence had never intended that I should follow the course of a man of action. I lacked the courage, I lacked the physical strength, and above all, I lacked all desire to play the part of a hero. I was a weakling of a boy, be-spectacled, narrow of chest and round of back, with a head out of all proportion to the rest of my body. At school I distinguished myself as a scholar, bringing home prizes term after term, but I had neither the wish nor the ability to succeed upon the playing-fields. Early in life I took up the study of Egyptology. It was fortunate for me that my father was a rich man, so that there was never any necessity for me to work for a living. I was only eighteen when I was left an orphan, a ward in Chancery; and when I came of age, I found myself the master of a fortune far more than adequate for my simple needs.

I desired nothing but to study; and, except in so far as money could assist me to learning, I had no need of my income, which rapidly accumulated in the bank. For forty years I worked unremittingly upon the subjects that fascinated me, that seemed to grow in interest in proportion as my knowledge expanded.

I became Professor of Ancient History at the University of Oxbridge, a Member of the Institute and a Professor of the College of France. I was also a member of the committee of the Egypt Exploration Fund, and an honorary D.C.L. of Oxbridge. I was only thirty-five years of age, when I was entrusted with my present responsibilities at the British Museum.

I state these facts for the benefit of the reader who is not acquainted with my particular branch of learning, that he may have the better reason to believe that my position is not one to tempt me to set down what is not true, for the sake of beguiling a few leisure hours. On the contrary, the scientist, above all things, should be a lover of the truth. The adventures that befell me are neither exaggerated nor disguised. If any one doubts me, let him journey to the ruined city of Mituni-Harpi, beyond the desert, in the valley of the Sobat.

CONCERNING SEROPHIS, PRINCE OF THEBES; THE FIRST APPEARANCE OF THE SCARAB; AND THE MYSTERY OF THE DEATH OF JOSEPHUS MACANDREW

I MUST describe the causes that led up to my extraordinary

adventures without entering into any unnecessary details in connection

with the customs and the history of the Ancient Egyptian people.

However, since my reader is in all probability not conversant with the

subject, a certain amount of explanation is essential. I will

endeavour to express myself as clearly and as briefly as possible, for

the edification of the inexpert mind, duly considering the facts of

the case in their chronological order.

I had for many years been aware of that series of beautiful tablets, representing the funeral procession of Serophis, to be seen in the temple at Karnac. The illustrations themselves, together with the accompanying hieroglyphics, supply ample evidence to the effect that Serophis was a "Prince of Thebes," a friend of Pharaoh, and a man of considerable wealth. Whether or not he was of royal blood it is impossible to say; neither is that point material. He may have been priest, scribe, or magistrate. Certain it is that his funeral rites were performed with all the pomp and circumstance of those of an emperor. With him was buried a veritable fortune in solid gold. The drinking flagons, the Canopic jars, the boxes and trays containing food, the weapons, sceptres, collars and batons of command, which were carried with the mummy to the tomb—all were of gold, and upon each of them was stamped the name and crest of this illustrious "Prince of Thebes." In the fifth painting of the series, the scarabaeus itself appears. It is carried by the priest who immediately precedes the mourners, and is drawn quite out of proportion to its actual size.

On my second Egyptian tour, when the excavations at Thebes were well in progress, I myself visited the temple at Karnac, and studied the inscriptions relating to the funeral of Serophis. I was of course deeply interested in everything I saw; but I remember, at the time, one thing in particular attracted my attention: namely, that the funeral of Serophis was represented as heading for twin mountain peaks. Upon the crest of one was perched a hawk; upon the crest of the other, a vulture; whilst at the base of the peaks, encircled by a sacred serpent, sat the figure of a god, with a lotus flower upon his head.

Now, Herodotus, the Greek historian—who is certainly not to be fully trusted in any matter relating to Egypt—tells us that the Nile finds its source between two mountains, called Mophi and Crophi. It is true that, in this case, two mountains would not have suggested the source of the Nile to me, had it not been that the figure seated at the foot of the mountains was undoubtedly that of Harpi, the Nile god, and that the two birds perched upon the peaks were representative of the Upper and the Lower Nile.

It must be understood that I did not arrive at the following conclusions at the time. But in the light of after events, when I had had the benefit of the advice and reasoning powers of the celebrated Mr. Wang, the whole matter was made clear to my understanding. The temple of Karnac affords striking evidence that Serophis was not buried at Thebes, but that his final resting-place was somewhere beyond the Nubian desert, towards the sources of the Nile.

The next link in this remarkable chain of evidence is supplied by the Mannae papyrus, the greater part of which is undecipherable. The partial translation which has so far been accomplished was undertaken by myself; and I remember my surprise at the time when, once again, I came upon the name of Serophis, Prince of Thebes, at the time of the Twelfth Dynasty.

Here there was further evidence, had I but eyes to see it, that Serophis was buried in Ethiopia; for it was during this Twelfth Dynasty that the greater part of the savage country to the south, towards the great Central African Lakes, was conquered by the Theban monarchs. Also, the most legible part of the papyrus contained a description of a journey undertaken by Serophis, in accordance with orders received from Pharaoh, to a country south of Meroe, that is to say, beyond the junction of the rivers where the city of Khartoum now stands.

The papyrus also informs us that the sarcophagus, or tomb, of Serophis was at Mituni. Now, I know of no Mituni save that which is called Mattanieh, in the Nome of the Knife, south of Memphis; and it is clear that no Theban potentate could have been buried there. Moreover, the place is mentioned a second time as "Mituni-Harpi"; so, once again, we have the Nile god in connection with the burial-place of Serophis.

Before going further into this matter, and turning our attention to the mystery of the scarabaeus itself, let us consider the evidence that was in my possession, prior to the advent of the scarab to the British Museum. Serophis, a prince of Thebes, was buried with the greater part of the treasure of his household, at a place called Mituni-Harpi, which is unknown to any Egyptologist, and is shown upon no ancient or modern map. There are reasons to suppose, however, that this place is situated in the country formerly known as Ethiopia, which is now called the Soudan.

We now come to the scarab. I am unable to give the date; but, strangely enough, I remember the morning in question in every detail. I was working in my own room in the British Museum, and, for the purpose of comparing certain hieroglyphics, I had gone into a little storeroom, usually kept locked, where a certain number of unexhibited specimens were kept. There, for some reason or other, I was seized with a fit of curiosity, and proceeded to ransack the place, discovering several things of interest. On finding a drawer locked, I searched for the key, which I eventually discovered in an envelope, as if it had been purposely hidden. On unlocking the drawer, I found it to contain a single parcel, about two feet in length and six inches in width. The parcel being heavy, and my curiosity aroused, I immediately opened it, and to my astonishment found in my hands one of the most magnificent green jasper scarabs I ever beheld in my life.

On examining it closely, I found it to be the scarabaeus of Serophis, who now seemed to be appearing and reappearing in my life at regular intervals, after the manner of the Wandering Jew. I did not at first attempt to read the hieroglyphics upon the scarab, as my first feeling was one of astonishment that such a relic should have been found in the British Museum itself, where, to my certain knowledge, it had never been indexed and registered. The tomb of Serophis was undiscovered, its locality was unknown. So far as the modern world of scientific learning was aware, none of the contents of the tomb had ever come to daylight. And here was the scarabaeus itself, appearing as if by magic in the British Museum; and I, who was personally responsible for the safe keeping of all such relics, had known nothing whatever about it, until I found it by chance.

In amazement, I regarded the sheet of newspaper in which it had been wrapped. It is fortunate that I not only noted the date, but kept the paper itself. It was a copy of The Times, dated February 25, 1881.

Before investigating the scarabaeus, I was anxious to ascertain how it had found its way into the Museum, where it appeared to have been for a number of years. I accordingly interrogated an attendant, who was at first able to give me no information likely to be of any value. On questioning him further, however, I ascertained that the only man who had been in the habit of using the drawers in the storeroom was an old custodian, of the name of Hayward, who had long since left the Museum.

That evening, I took the scarab home with me, and locked it up in the left-hand bottom drawer of my pedestal writing-desk. That is an important point. Having found out Hayward's address, I visited him that same night and put to him certain questions which he at first hesitated to answer. Eventually, however, I got the truth out of him.

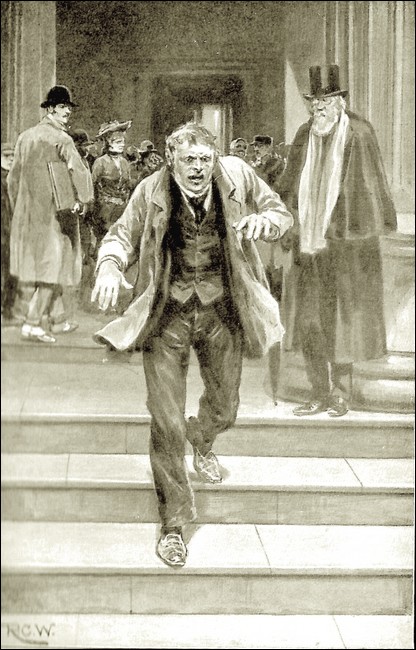

It appears that, at about four o'clock on a winter's afternoon, in the year 1881, Hayward was on duty in the Ancient Egyptian section of the Museum, when a middle-aged man, who appeared to be wildly excited, rushed up to him and seized him by the lapel of his coat. Before Hayward had time to say a word, something weighing about five or six pounds, wrapped up in a table-napkin, had been thrust into his hands. On being asked by Hayward what it was, the stranger had cried out, "Take it, for Heaven's sake! Take it, and beware of Psaro!" At that, the man had fled, rushing down the steps of the Museum as if he were pursued by evil spirits. Hayward described him as being middle-aged, and apparently in the greatest state of alarm, also mentioning that he was very sunburnt—and be it remembered that it was then the depth of winter. Though he must have passed through several of the crowded London streets, he was wearing no hat and a pair of bedroom slippers; from which it was evident he had left his home at a moment's notice, and in the greatest haste.

Rushing down the steps of the Museum as if he were pursued by evil spirits.

Hayward had very personal reasons for desiring to keep what he knew a secret; and in consequence, it was no easy matter to get the whole story out of him. I now, for the first time, set down the truth, much as I had it from him.

Hayward, on unrolling the table-napkin, had discovered a green jade scarab. He had no knowledge of scarabs, and could not say whether the thing was of any value. With the idea of selling it to the Museum authorities, he took it to his home; and from that moment a series of the most astonishing misadventures befell him.

A chimney fell upon the roof of his house, and his child—a little girl of five years of age, who was sleeping in an attic—narrowly escaped with life. His wife was taken dangerously ill, and for several weeks her life was despaired of, though, he assured me, the doctors were never able to discover the nature of her illness. The little money the man had saved was lost in a notorious bank smash. And finally, Hayward himself, whilst crossing Oxford Street on his way to the Museum, was run over by a hansom cab, and carried home with a broken leg.

He had by now come to the conclusion that his possession of the scarab was responsible for his ill-fortune. What reasons he had for thinking it, I cannot say. Those who are by nature superstitious are adepts in finding explanations for such examples of coincidence. At any rate, he had quite made up his mind to get rid of the scarabaeus before the astonishing revelation of the Bloomsbury Mystery.

Hayward had kept the table-napkin in which the scarabaeus had been wrapped, and he had observed that it was very clearly marked with the name of "Josephus MacAndrew." Now, quite apart from the fact that the description of the murdered man as given in the newspapers tallied with that of the excited stranger who had burst upon Hayward in the galleries of the Museum, the name, Josephus MacAndrew, is sufficiently singular and uncommon to leave no possible room for doubt. After the scarab had been in the possession of Hayward for a matter of three weeks, Josephus MacAndrew was murdered in his house in Bloomsbury Square. On reading this, Hayward was determined to rid himself of the scarab with as little delay as possible, and to say nothing about it to any living soul. When he returned to duty, he brought it with him to the Museum, wrapped it up in an old newspaper, and hid it in the drawer in which I myself found it many years afterwards.

With this story fresh in my mind, I immediately returned home, and went at once to the left-hand bottom drawer of my writing-desk, with the object of examining the scarab. Imagine my amazement when, on unlocking the drawer, I discovered that the relic had gone! I searched the whole room, and eventually found it in an old chest containing several objects of Egyptian and antiquarian interest.

I am, I confess, inclined to be absent-minded; and it is, I suppose, possible that I made a mistake. None the less, I feel convinced that I originally put the scarab in the bottom drawer of my writing-desk, and not in the chest. It is also possible that a servant moved it, since the key was in the lock; but, this is hardly likely, since there could have been no object in so doing, and none of my domestics are allowed, on any pretext whatsoever, to touch anything in my study.

Be that as it may, I took out the scarabaeus, and, seating myself at my desk, placed it before me on the table. Very carefully, I unfolded the paper in which it was wrapped; and, as I did so, my eye caught the following headline: "The Mysterious Murder in Bloomsbury."

For the next few moments I had forgotten all about the scarab. I found myself engrossed in the sordid details of one of those sensational mysteries which, from time to time, perplex and thrill the people of London. Josephus MacAndrew had been a well-to-do retired silk merchant, a bachelor. For no apparent reason he had been foully done to death, on a night when he was alone in his house, his sole attendant—an old butler—being away at the funeral of a relative. After the murder, the house had been ransacked from roof to cellar. Drawers and cupboards had been broken open; carpets had been taken up; cushions and mattresses had been ripped to pieces; the stuffing had been torn out of the chairs. It was evident to the detectives who investigated the case that a most thorough and systematic search, which must have occupied several hours, had taken place either before or after the murder. And yet, in the eyes of the police, the most remarkable thing in connection with the whole affair was that nothing whatever had been stolen, although the house contained several valuables.

I ask you to consider how unknowingly I, a man of peace and a scholar, was led, as it were blindfolded, into this maze of mystery and danger. The account of the murder, as related by The Times, concluded with a fragment of evidence that conveyed nothing to the police, but which to me was charged with amazing, almost unbelievable, significance.

In the room where the murdered man lay, milk had been sprinkled upon the floor, although the murderers had had to descend to the kitchen to procure it. Drawn in chalk upon the floor was the figure of a man with a fox's head.

This was enough to assure me that the crime had been perpetrated by persons who retained the customs and rites of the Ancient Egyptians. There could be no question that the picture on the floor had been intended to represent the Egyptian god, Anubis, the jackal deity who was lord of death. To my mind, this in itself was enough to prove the case, without the evidence of the milk upon the floor—one of the Ancient Egyptian funeral rites—a custom practised invariably by that interesting and wonderful people, and to the best of my knowledge known to no later civilisation.

I was now deep in a mystery that appalled me, that I was wholly unable to explain.

The advanced civilisation of Ancient Egypt ceased five hundred years before the dawn of the Christian Era. We have a record of fifty-five monarchs as reigning after the death of the last Theban Pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty, but, so far as we know, the Ancient Egyptian civilisation, language, and customs, became extinct after the Persian conquest. And yet, here was I, Miles Bowater Unthank, Professor of Ancient History, face to face with indisputable evidence to the effect that, only a few years before, Josephus MacAndrew had been murdered in London by people who retained the customs and apparently the religion of the ancient inhabitants of the Valley of the Nile.

Allowing the newspaper to fall to the ground, I turned my eyes upon the scarabaeus—the green, polished surface of which reflected the light from my study lamp—with feelings of mingled wonderment and awe. I have handled Ancient Egyptian curiosities all my life; but never before or since have I experienced a like sensation. As I lifted the scarab to examine it more closely in the light of the lamp, I became on a sudden conscious of the fact that I was trembling in every limb, and I found myself repeating—though I know not why—the words, "Beware of Psaro!"

OF THE SCARABAEUS ITSELF, AND OF MY FIRST INTRODUCTION TO JOSIAH MACANDREW, BARRISTER-AT-LAW

WE now come to the consideration of the scarabaeus itself.

It was unquestionably the most remarkable and the most interesting

relic of its kind that I ever beheld. But, first, for the benefit of

the uninformed, let me explain exactly what a scarab is.

Briefly, a scarab is a beetle—to be more scientific, a particular family of beetles, distinguished by the largeness of the head, and a fringed, fur-like plate at the extremity of the mandibles, known to zoologists by the name of Scarabeidae. Of this family, one genus, Scarabaeus sacer, the Sacred Egyptian Beetle, is an insect, represented in many tropical countries, which, as a scavenger, renders considerable service to the community.

It is beyond doubt that the Ancient Egyptians were fully sensible of the benefits accruing from the presence of great numbers of scarabs upon the banks of the Nile. In the earlier stages of civilisation, all manifestations of Nature, all plants and animals serviceable to man, are held to be sacred, and often become personified as gods. Thus, in Ancient Egypt, not only the sun and the Nile herself, but various creatures were gifted with divine and sacred powers, such as the bull, the jackal, the ibis, and the beetle.

The name of the Beetle-god was Khopri, and he was represented either as a disk, enclosing a scarabaeus, or as a beetle-headed man—just as Anubis was the jackal-headed, Thot the ibis-headed, and Horus the hawk-headed god.

Khopri is frequently identified with Ra, the sun-god; but with that we are not concerned—I have no wish to embark upon a lengthy dissertation upon the subject of Egyptian mythology. It is sufficient to observe that Khopri was gifted with certain attributes of his own. A theory which I myself advance is that the beetle, being the natural opponent of decay, shared with the sun the privilege of being lord and master of long life and health, and for that reason his representation was invariably buried with the dead, in the form of a stone or metal image, to act as an amulet, or charm. Certain it is that there are few Egyptian tombs in which such ornamental scarabaei have not been found.

The great artistic skill of the early Egyptians is clearly exemplified in the scarabaei, carved with infinite symmetry and precision, in such difficult materials as granite, jasper, and jade. But, I repeat, I have never beheld a more beautiful piece of work than the scarabaeus of Serophis.

It was, as I have said, about two feet long by six inches wide, with a thickness of about four inches in the middle, convex upon the upper surface, flat upon the bottom, which was covered with hieroglyphics so minute that, in order to read them, I was obliged to use a powerful magnifying-glass.

Upon the upper side was a representation of the god Khopri in his bark, upon the sacred waters of the Nile. From both prow and stern a lotus flower drooped gracefully, as if in adoration, towards the figure of the Beetle that, with wings outstretched, stood upright upon its hind legs, beneath an awning, before which stood the death-god, the jackal-headed Anubis, with folded arms. The throne upon which was the god bore the words, Mituni-Harpi, with which I was already acquainted.

Still, it was the reverse side of the scarabaeus which interested me more than the figure of the god, with which I was well familiar. The hieroglyphics were exceedingly small; but, with the help of the magnifying-glass, I was able to read them without difficulty, since they were in a perfect state of preservation. I will not translate the hieroglyphics literally, for that is neither possible nor necessary. It is enough for me to transcribe the meaning of the message which the scarabaeus was intended to convey to posterity.

It began with minute, but concise, directions as to how the tomb, or sarcophagus, of Serophis might be entered. Upon Ancient Egyptian tablets the sacred beetle was often represented as seated upon the head of the sun-god, Ra. At the entrance to the tomb there was apparently an image of Ra; and according to the legend upon the scarab, it was but necessary to place the scarabaeus itself in a recess or slot, which was there to receive it, upon the head of the sun-god, Ra. And thereupon, one is asked to believe, the tomb would open of its own accord.

This may appear a miracle suggestive of the "Open Sesame" of the Arabian Nights. I will not pretend for a moment that I believed it at the time. As a student of Egyptology, I was, of course, interested; but never for a moment did I regard the thing in a practical light. I learnt afterwards, and the reader will subsequently discover, that the whole affair was perfectly simple. There was certainly no magic in any way connected with an elementary problem in dynamics.*

(* I am informed that, for this particular class of literature, I use an unnecessary number of long words. Frankly, I consider there is no justification for such a statement. On re-reading what I have written, I am of opinion that I have made myself quite intelligible to the average reader, who, if he is unaware of the object of the science of dynamics, can refer to an encyclopaedia, or even a dictionary—for the former word is, I observe with regret, of six syllables.—M. B. U.)

The greater part of the hieroglyphics was concerned with "The Curse of the Beetle." Unless you are acquainted with the personalities of the Ancient Egyptian gods, and appreciate the Egyptian conception of the life hereafter, I fear it would be hopeless for me to attempt to give you a literal translation of the extraordinary malediction. A paraphrase will meet the case.

The Curse of the Beetle.

The watchers of the tomb of Serophis shall abide for ever; a sacred injunction is laid upon them to guard the mummy of the bygone Prince of Thebes, until "man ceases to dwell upon the earth, until the gods descend from the four corners of the heavens." The office is to be carried out by the watchers, their descendants, and their descendants' descendants, throughout the centuries; for it is not meet that the sarcophagus of Serophis should be despoiled.

Upon him who is the first to enter the Tomb, the Curse of the Beetle rests. Anubis lies in wait to conduct him to the Everlasting Shades, where he will survive in torture. The sepulchre must be entered periodically by the priests who have charge of the sarcophagus, for the purpose of offering up prayers for the soul of Serophis. But no one else may enter; and he who steals the scarab, with the intention of gaining access to the tomb, falls under the malediction of the great god, Khopri. Misfortune and disaster will dog his footsteps. So long as the scarabaeus is in his possession, he will find neither rest nor peace nor happiness. He will be tracked and hunted from one end of the world to the other; he will be doomed to pass "beyond the Lands of the Sun, where the red waters of the Nile find their birth, and the winged beasts of the desert are not able to survive." The Curse of the Beetle lies upon him who lays hands upon the scarabaeus of Serophis, who endeavours to penetrate into the sacred precincts of the tomb of Mituni-Harpi.

I confess that, when I had deciphered this inscription, I was not in the least dismayed. I am not a bold man, as I have said, but I have for so long been acquainted with Egyptian myths and legends that I could not regard the admonition in any other light than that of a scientific curiosity. That there was any truth in it, I did not for a moment suppose; and even now, I will not go so far as to admit for a moment that I believe in the mystic powers of the scarab.

I am unable to say what I intended to do with the scarabaeus. It was apparently my own property. It certainly did not belong to the Museum. Its rightful owner—namely, old Hayward—had refused to have anything to do with it. I have little doubt that I would have handed it over to the Museum, as "presented" by myself, had not, on the very day after I found it, an extraordinary coincidence come to pass.

I was at breakfast, when my man-servant informed me that a gentleman wished to see me. Remarking to myself that it was a somewhat unusual hour to call, I rose to my feet and wont into my study, where I encountered a personage of somewhat remarkable appearance.

He was extremely tall and attenuated, with thin, coal-black hair, plastered by means of Home kind of cosmetic across a head that was otherwise bald. He was clean shaven, but his complexion was so dark, and his cheeks and chin so blue, that he had every appearance of not having shaved for a week. His eyes were large, black, and lustrous, and had a singularly piercing effect, as if they looked clean through you. His chin was massive and square, suggestive of exceptional will-power.

I bowed politely, asked him his name, and for what reason I was indebted for the honour of his visit. He answered me in a voice which I can only describe as sepulchral—it appeared to come from his boots; and though he spoke in little above a whisper, the sound of it seemed to go echoing about the room, like a distant peal of thunder.

"I'm a lawyer," said he, "a barrister. My name is Josiah MacAndrew."

I caught my breath.

"Any relation, may I ask, to—Josephus MacAndrew? But, perhaps, I presume?"

"Not at all," said my visitor. "Josephus MacAndrew, who was murdered in Bloomsbury Square, in the year 'eighty-one, was my uncle."

"Indeed," said I. "The object of your visit is, of course, in no way connected with that tragedy?"

"Pardon me," said he; "it is. It has a great deal to do with it."

I was more than a little surprised. To tell the truth, I was beginning to feel exceedingly uncomfortable. However, I did my best to preserve an attitude of politeness, such as is becoming in a host.

"You interest me," said I. "Pray take a seat." I motioned him to a chair.

He sat down, stretched out his long legs across the hearthrug, at the same time emptying his pockets of a great number of notebooks, which he set down carefully upon a small table that happened to be at his elbow. He then cleared his throat and began.

"Professor Unthank," said he, "I have been led to understand that you are the greatest living authority on the subject of Ancient Egypt?"

I acquiesced with a bow. Modesty forbade that I should speak.

"You may not be aware," he continued, "that my uncle, Josephus MacAndrew, was deeply interested in the subject upon which you have established your reputation. He was a man who had travelled much. In the course of his business as a silk merchant, he visited several countries, and afterwards, when he retired, he continued to travel. He had a remarkable fund of knowledge. Now, Professor, I wish to ask you a plain question, and to receive, as from a man of honour and truth, a plain answer." He paused, looking at me with his black, piercing eyes.

"I am at your service," I faltered, for I was by no means at my ease.

"Have you, or have you not," he asked, "any knowledge as regards the whereabouts of the scarabaeus of Serophis?"

When MacAndrew said these words, I honestly believe that any one could have knocked me down with a feather. I know that I was unable to reply for quite a considerable time. I had to assure myself that I was wide awake, that I was not dreaming. Serophis, Prince of Thebes, had been dead a matter of two thousand five hundred years, and yet, it now seemed that he was haunting me. None the less, I was by no means inclined to state a falsehood. I answered truthfully, as soon as I had recovered from my surprise.

"A few days ago," said I, "I should have been obliged to answer your question in the negative. I can now tell you that it so happens that I not only know something about the scarab of Serophis, but it is actually in this room."

At that, he sprang to his feet. He was like a man transfigured. He stood before me at his great height, shaking in every limb, as if from excitement. His voice was like the roar of a savage beast. I was startled, to say the least of it.

"In this room!" he echoed. "Where is it? Let me see it! Show it to me, now!"

I looked at him in amazement, and then got to my feet, and went to my writing-desk, pulling out the bottom drawer, where I had put back the scarab the previous night. It was not there. I went at once to the oak chest, where I again found it. It was no longer wrapped in the old newspaper. I handed it to MacAndrew.

From the casual way in which he examined the image of Khopri, afloat on his bark upon the sacred waters, I saw that he was no student of Egyptology. He turned the scarab over, showing the flat side, upon which were the hieroglyphics.

"Can you read all this?" he demanded.

I was somewhat nettled at his abrupt behaviour. I informed him that I was well able to decipher the inscription.

"What does it say?" he almost shouted.

I asked him to calm himself, and motioned him to his chair, where he again seated himself with reluctance. From the manner in which he kept snapping his fingers and shuffling his feet, I saw that he was highly agitated.

I then proceeded to translate the inscription, word for word, explaining the references to the Egyptian deities. He listened to me with what I can only describe as a kind of feverish attention, and when I had done, he held out a hand, asking permission to look at the scarab again.

"What does this mean?" he asked, indicating the hieroglyphics on the throne, upon which the beetle-god was standing.

"That is Mituni-Harpi," said I; "the place where Serophis is presumed to have been buried."

"Exactly," he replied. "And are you aware of the locality of this place, Mituni-Harpi?"

I shook my head.

"Then, I am," said he.

I looked up in surprise. It was a morning of surprises.

I informed him that he was in possession of a piece of knowledge that was shared by nobody else; that no student or scholar of Ancient Egyptian history had ever been able to discover the whereabouts of the place. He replied in a voice of thunder, striking his pile of notebooks with a fist.

"I have here," he cried, "every detail that is necessary to enable me to make a journey to Mituni-Harpi to-morrow."

"Do you intend to go there?" I asked.

"I do," said he, "on one condition."

"And what is that?"

"That you come with me."

I started again. For a moment, I thought the man was mad.

"But that is out of the question," I protested. "I have my duties here in England, both as a Professor and a Curator."

MacAndrew rose from his chair, and placed a long, thin hand upon my shoulder.

"Professor Unthank," said he, in his sepulchral voice, "I intend to journey to the tomb of Serophis, and, for a variety of reasons, I hope that you will consent to accompany me. Pray be seated; I will explain the matter in detail."

His behaviour was as rough as his manners and his mode of speaking were abrupt. He literally shoved me back into my chair, and then produced from the inside pocket of his coat something which I recognised at once as an Ancient Egyptian papyrus, a scroll decorated with hieroglyphics.

OF THE STRANGE JOURNEY OF JOSEPHUS MACANDREW; AND OF HOW I MADE THE ONE RASH RESOLUTION OF MY LIFE

HE placed the rolled papyrus upon the top of his pile of notebooks,

and then clasped his hands upon a knee uplifted. I could not help

noticing his hands; they were at once refined and suggestive of

unusual physical strength.

"Many years ago," he began, "my uncle purchased this papyrus from an Arab hawker in the streets of Cairo. He had no idea at the time of the value of the information it contained. He could not read the hieroglyphics, and bought the thing merely as a curiosity.

"On the death of my uncle, I inherited his effects. He had a considerable library, for he was a great reader. As for myself, I read little, except works of jurisprudence and the daily newspapers.

"Recently, I discovered amongst my uncle's possessions these notebooks, the contents of which filled me with amazement. My uncle had been, I knew, a great traveller; but I never had any idea that he had undergone such extraordinary experiences. One of the notebooks is written in the form of a diary. It is largely from this that I have gleaned the greater part of the story I am about to tell you.

"The papyrus—which I cannot read myself—is genuine. It consists of an inventory of the household effects of Serophis which were buried with the mummy at Mituni-Harpi. My uncle calculated that, apart from their value as relics of ancient art, the intrinsic worth of these golden implements and utensils amounted to a sum of not less than a quarter of a million pounds. Do you yourself, Professor, consider that possible?"

I replied to the effect that I thought the existence of such a treasure very improbable in an Ancient Egyptian tomb. That it was impossible, however, I would not go so far as to say.

"Am I right in believing," asked Mac Andrew, "that the contents of the sarcophagi and catacombs are to be regarded as the property of the Egyptian Government?"

"Certainly," I answered.

"Even if the sarcophagus in question were to be situated in the neighbourhood of the source of the Sobat?"

"That is another question," said I. "I did not know that any one had yet discovered the source of the Sobat. It is either in Mongalla or the Kafa district of Abyssinia."

"Neither do I know where it is," said he. "But I know how to get there, and there I intend to go."

"For what purpose, may I ask?"

"In order to gain possession of the treasure of Serophis."

"That is easier said than done," said I, "even admitting that you know how to accomplish such a journey. And have you any special reason to desire my company?"

"Before I came here," said MacAndrew, "I had several reasons. Now, I have one more: namely, that you are in possession of the scarab, which I can only describe as the key that unlocks the tomb wherein this fortune is stored."

I nodded. I was growing intensely interested. The pursuit of wealth held no attractions for me; but, from what I had heard, it seemed I was on the track of a discovery of the greatest scientific and archaeological interest.

"And your other reasons?" I asked.

"You are an authority on the subject. You could probably make yourself understood to Ancient Egyptians."

"That is possible," said I. "At the same time, I am never likely to be called upon to attempt to do so. The Ancient Egyptian language has been dead for centuries."

MacAndrew smiled, and leaned back in his chair, shifting his hands to the back of his head. In this position he regarded me for some moments without speaking, with a half-amused expression upon his face.

"You are entirely wrong," said he. "The Ancient Egyptian language is not dead. It is spoken to-day; it is spoken at this present moment, whilst you and I sit talking here in London."

"Where?" I asked, incredulous.

"At Mituni-Harpi," said he.

I was unable to believe. If I heeded him at all, it was merely because the man seemed so sure of what he was saying.

"How do you know all this?" I asked him.

"Listen," said he, "and I will tell you. Somehow or other, my uncle discovered the whereabouts of Mituni-Harpi. He was a man in whom was the spirit of adventure. Little dreaming of what he was about to do, or the hardships he would be called upon to undergo, he undertook to journey there himself. See, here is a map of the route."

MacAndrew produced a large sheet of parchment, which he unfolded upon the table. The parchment was very dirty, and torn in several places, where it had been carefully mended with transparent paper. The map, which was coloured, had been drawn in Indian ink, and the writing, where capital letters had not been used, the same as that in the several notebooks—a neat, somewhat cramped style of writing, though plain to read. I rose from my seat and looked over his shoulder, as he traced, with a forefinger upon the map, the actual route which his uncle had taken to the tomb of Serophis, the former Prince of Thebes.

Josephus MacAndrew, many years before, had passed up the White Nile, and thence entered the valley of the Sobat. He had journeyed into a savage country, beyond the town of Ajak, to a place where there was a cataract, at the foot of which was a Niwak village, inhabited by a tribe of Nilotic negroes—from the account of them he rendered, closely related to the Shilluk—living in large, circular, conical huts, of about forty feet in diameter, the roofs being made of thatched straw, the walls of chopped straw and clay.

Southward and westward of the village lay a desert which—if the map was drawn to scale—must have been more than three hundred miles across. Upon this desert, no oasis was marked, no town, village, stream or hillock. The blank pace upon the map was relieved only by one glowing, pregnant sentence: "Here upon this sandy waste, the sun beats like fire."

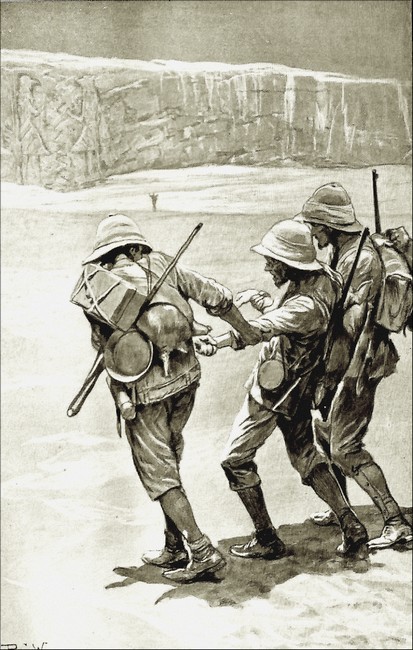

The desert terminated towards the south-west in a tableland which, according to a note upon the map, ended abruptly in a perpendicular cliff, several hundred feet in height, extending as far as the eye could reach, both to the north and to the south.

On referring to one of the notebooks, I ascertained that it was possible to ascend to the tableland only at a place where two gigantic images of the Egyptian gods, Thot and Anubis, were carved upon the bare face of the rock. Between these two colossi there ascended flight upon flight of steps to the higher level above. These steps were reported to be much worn by the action of water, though easy to negotiate in daylight. And so remarkable were Josephus MacAndrew's powers of observation and his eye for detail, that he had actually counted the number of these steps, which amounted to no fewer than three hundred and sixty-five—the number of days that it takes the earth to complete its orbit around the sun. In other words, allowing that each step was one foot in height, the bare cliff that rose like a wall at the extremity of the desert, was exactly the same height as St. Paul's Cathedral, measured from the pavement to the top of the cross.

At the head of the steps—if the observations in the notebooks were to be believed—one found one's self upon an extensive plateau of rich and fertile grass-land, extending for about forty miles to a range of mountains to the south. In former times, there had evidently been a path leading from the steps to the mountains; but this had been obliterated in the course of centuries by the action of rain, and was now grown over by the thin, waving grass that flourished upon the tableland. The route of the pathway, however, was easy to trace by means of a series of stone images, each of which was exactly the same, both in size and in design, representative of a Sitting Scribe, similar to the well-known statue which is to be seen in the Museum of Gizeh.

The Path of the Sitting Scribes conducted one to the foot of the mountains where was situated the town that went by the name of Serophis, at a short distance from which—according to Josephus MacAndrew—was a place in the mountains called Mituni-Harpi, where was to be found, in the vaults beneath the temple of the Sun-god, the sepulchre of the bygone Prince of Thebes and all the treasure that had been conveyed into his tomb, as illustrated upon the tablets to be seen in the temple at Karnac.

In the city of Serophis itself, Josephus MacAndrew had found a race of people, corresponding exactly in customs and physical characteristics with the Ancient Egyptians, the former inhabitants of the Valley of the Nile. Moreover, the language they spoke, the temples where they worshipped, their houses, palaces and streets, were in all ways similar to those of the subjects of the Pharaohs. If the statements made in his notebooks were correct, he was very much to be envied. He had had the privilege of seeing with his own eyes the civilisation of the Past, just as if he had been transported bodily, backward throughout the centuries, into a forgotten and a vanquished world.

He had either been mad, and the whole thing a fabrication, or else he had been one of the most fortunate of men. However, he did not seem sensible—so far as I could gather from his notes—of the scientific import and world-wide significance of his discovery. The sole motive of his journey across the desert had been cupidity, a desire to attain wealth, to rob the tomb itself.

This was not so easy as he may have thought. And though he told us little or nothing concerning it, it seems that the sarcophagus was guarded by the most vigilant of priests, who kept watch day and night in the temple erected above the tomb.

And this in itself was one of the many points that served to convince me that there was more than a little truth in the story, fantastic and absurd as it might appear. I could not dispute the accumulated circumstantial evidence that was now in my possession. The scarab had already informed me of the injunction laid upon the watchers of the tomb of Serophis who, for generation upon generation, should "abide for ever, until man ceased to dwell upon the earth, until the gods descended from the four corners of the heavens."

During his sojourn in the city of Serophis, Josephus MacAndrew seems to have awaited his opportunity, and on one occasion to have succeeded in entering the vaults. What happened exactly will never be known. Apparently, he gained possession of the scarabaeus, but failed to penetrate into the tomb itself. He speaks of flying for his life, of a pursuit along the "Path of Sitting Scribes," with those who were thirsting for his blood hot upon his track. And on a sudden, as I was reading this, it was as if a blow had been struck me, when I remembered the tragic circumstances of the man's death.

The newspaper, such a prosaic and familiar object as a copy of the London Times, supplied another link in this amazing chain of evidence. Already, I had been struck with the suggestion that the man had been murdered by Ancient Egyptians, which I had at once discarded as impossible. Could it be that the priests of Serophis had come forth from their buried home beyond the trackless, arid desert, and had followed the doomed man into the very centre of the civilisation of the modern world, where, with ancient rites and ceremonies, they had done him brutally to death?

The more I thought of it, the more I believed it true. Josephus must have learned quite suddenly that he had been tracked to London. Hence his hurried entrance into the Museum, and the excited manner in which he had thrust the scarab into the unwilling hands of Hayward. And the murder itself was explained: the Egyptians had ransacked the house from roof to floor, in their search for the missing scarab. Needless to say, their quest had been futile. But it was easy to explain the perseverance with which they had hunted down the thief and the thoroughness with which they had searched the house in Bloomsbury Square. The scarabaeus was the key to the tomb. If it were lost, the entrance to the sarcophagus was closed for ever.

For the first, and I believe the only time in my life, I felt my blood coursing swiftly through my veins. In an old gilded Empire looking-glass, which stands above the mantelpiece in my study, I caught the reflection of my own face, and was amazed. I was flushed; my eyes were bright. I felt that my hands were trembling.

I had forgotten all about MacAndrew, who was still seated in his chair, regarding me steadfastly with his black, piercing eyes. I had forgotten all about the scarab. I was conscious only of one thing: that somewhere in the heart of Africa, beyond the ken of European man, there existed a city, such as Thebes and Sais and Memphis. I remembered all that my learning and my imagination had conceived of narrow, crowded streets, choked with the booths of merchants, down which passed caravans, returned to Egypt with the spices of Arabia, the gold of Ophir, precious stones from Elam, the wine-skins of Pelusium.

Often, in the solitude of my study, or the stillness of the great Museum, had I heard the clash of cymbals, the beating of drums, the tramp of thousands of feet. I had seen the city gates thrown open, and the army of Pharaoh march forth to war.

First the chariots—the charioteers, armed with bows and great shields, looking down scornfully upon the people, whilst the white dust rises in clouds from beneath the hoofs of their prancing steeds. Then the light troops, stripped to the waist, swinging forward at a pace that is half walk, half run—sinuous and supple men of war, each armed with bow or axe or boomerang.

A blast of the trumpet, and there surges through the gate the Libyan Shairetana, Pharaoh's Bodyguard, recruited from the most warlike race in Africa. Great soldiers these, each man standing taller by a head than the Egyptian of the Nile; thick-lipped, bearded warriors, broad of chest and shoulder, to whom battle is but a pastime and plunder the victor's rightful prize. Their great double-edged swords glitter in the sunshine. Their long, tight-fitting jerkins are striped black and white. They march in step, with closed, even ranks, disciplined and drilled. The terror of their name has been passed by word of mouth from the mountains of Assyria to the confines of the Ethiopian Desert.

Then the great captains pass, each in his chariot, attended by his standard-bearer and his officers: and, at last, Pharaoh himself, clad from head to foot in glittering armour, unconcealed by the long cloak that flies out behind him on the breeze, driving his own milk-white stallion, armed to the teeth with spear and bow and sword. The noble head of the animal is held right hack by means of a bearing-rein, so that he can proudly toss the great grey ostrich plumes that crown him. His back is covered with a saddle-cloth of embroidered, beaten gold; whilst at the side of the chariot a tame lion, with red tongue lolling from its mouth, follows its master like a dog. Whether he be Rameses or Seti, he is Pharaoh, a god become flesh, the scion of Osiris, Emperor of the World.

The rest of the Army passes: a tribe of faithful Bedouins, wild men of the desert who have survived the centuries; Grecian mercenaries; and last, the legions of the Infantry of the Line, sallying forth to conquer the vile Khita or to erect the monoliths of Rameses upon the distant Syrian hills.

I had pictured all this, time and again, from the days of my youth. I had lived the long hours of my secluded and studious life in the midst of this wondrous, bygone people. I had worshipped at the shrine of Horus; I had seen the perfumed incense, scattered by the priests, rise in the great, dim nave of the temple, whilst a chant swelled in adoration to Isis, Queen of the Nile, who was before Astarte and Ishtar, and that fair goddess who was worshipped by the Greeks.

I had dreamed that I had heard the long-haired mourners bewailing the death of kings. I had even journeyed in my fancy upon the ferry-boat that crossed the sacred river to the kingdom of Osiris, the eternal land, where I had set eyes upon the sacred sycamores, in whose shade are weighed the hearts of men that the goddess of Truth may declare them innocent of sin.

For years this had been the all-absorbing subject of my dreams. I had lived with an ancient people; I had shared their hopes and passions, their labours and delights. I had marvelled at their diligence and skill; I had rejoiced in their victories and triumphs; I had witnessed their sufferings in times of famine, pestilence and death.

And now, it seemed, as by a miracle, I could see them with my living eyes, speak to them and hear their music and their songs. The history of the Nile burned within me like a fever. On a sudden, I became conscious that MacAndrew was before me, that he had seized me by a hand.

"I'm coming with you," I cried like a madman. "I'm coming with you, to the ancient sources of the Nile!"

This was the one rash and thoughtless resolution of my life. The time was to come when I was to repent bitterly the blind, senseless impulse that sent me, like a truant schoolboy, upon an errand that was fraught with mystery and danger.

OF CAPTAIN CROUCH AND THE TWO STRANGE HANDS ON BOARD THE "WESTMORELAND"; AND OF THE DISAPPEARANCE OF THE BEETLE

MACANDREW and I spent the whole of that day together—indeed,

every day for a fortnight. I studied Josephus MacAndrew's notes; and

the more I read, the more convinced I was that I was about to make one

of the greatest discoveries of modern times. We procured geographical

works, relating to the country of the Upper Nile, and the savage negro

races who inhabited it. We went thoroughly into the matter of our

outfit, the equipment and armoury that we would require.

MacAndrew threw up his legal engagements, and I so arranged matters that I should be free for a year, handing over my duties to my old friend, Professor Thistleton, of whom no doubt you have heard. As far as MacAndrew and myself were concerned, we divided our responsibilities. He was entrusted with all matters relating to the expedition itself: the procuring of provisions, guides, servants, pack animals, etc., whereas I was responsible to him for everything that can in any way be described as scientific. I had charge of the medicine chest, the compass, and the sextant we agreed it would be advisable to take. He also naturally relied upon me in all matters relating to Ancient Egypt, the translation of hieroglyphics, and similar knowledge.

It must be understood that we were undertaking the journey, each with a different object. MacAndrew desired to obtain the treasure. Why he wanted it, I do not know. He was tolerably well off. He had certainly never disguised the fact that, from Ms point of view, the expedition was nothing else but a treasure hunt. As for me, I looked upon the whole thing as a voyage of scientific discovery and research. I fondly believed that I was about to glean information, which in archaeological interest would rival the discoveries of the first excavations, or Rawlinson's solution to the problem of the cuneiform inscriptions.

I shall never forget the day upon which we left the London docks. Our luggage had gone before us, a great quantity of boxes and packing cases; and MacAndrew and I went down by train from Fenchurch Street station.

We found our ship, which was called the "Westmoreland," and went on board at once. She was due to sail within an hour, and would call at no port, except Malta, until Alexandria was reached. I remember I was wearing a fur overcoat, for it was a bitterly cold day. MacAndrew had gone below, and I paced the deck for some minutes endeavouring to keep myself warm.

I had gone to the stern part of the ship, and was looking down into the water—the mud-coloured water of the Thames, upon which every kind of refuse was floating. Gradually I became conscious of the most noxious and offensive smell. I thought at first that it proceeded from the garbage afloat upon the water, and then I perceived that clouds of smoke were drifting slowly past my head.

Turning, I beheld, for the first time, Captain Crouch. He was a small man, with very pronounced and angular features, and a small goat's-beard growing beneath his under-lip. In spite of the cold weather, he wore no overcoat, though both his hands were thrust deep into his trouser pockets. His legs were widely separated, and his sailor's cap thrust well back upon his head.

In his mouth was an enormous, hooked pipe, from which the smoke which had so offended my nostrils was issuing in clouds.

"Afternoon," said he, with a nod.

I repeated the formality.

"Egypt?" he asked.

"Yes," said I. "My friend and I are going to Alexandria."

"You're Professor Unthank?" said he.

I felt flattered that he was acquainted with my name. I remember I remained for some time on deck conversing with Captain Crouch. I thought him, then, a very mild and polite little man. He expressed a hope that I should be comfortable on board the "Westmoreland." He told me of the difficulties he had experienced in getting a crew, saying that, at the last moment, two natives had signed on, whose nationality was a mystery.

"There they are," said he, pointing to two men, who stood upon the forward well-deck, leaning upon the bulwarks, one of whom, I noticed, was disfigured by an ugly scar upon his cheek. He was an old man, with a face creased and wrinkled like the palm of a monkey's paw.

"I've travelled the world, Professor," said Captain Crouch, "and I know most of the races of the world: Koreans, Patagonians, Andaman Islanders, hairy Ainus—races that not many people are acquainted with. But I never saw the like of these sportsmen. If they were not so light of skin, and did not grow their hair so long, I should say they came from Abyssinia."

"They have not the white teeth of an Abyssinian," said I.

"Nor yet the physique," said Crouch.

I confess I was conscious of a feeling of dismay when I made the next remark. I was thinking, indeed, of the fate of Josephus MacAndrew.

"If we can trust the pictures that accompany the hieroglyphics," said I, "those men bear a remarkable resemblance, both in feature and physique, to the inhabitants of Ancient Egypt."

Captain Crouch shrugged his shoulders, evidently dismissing the matter from his mind. A little after, he went to the head of the gangway and greeted the pilot, who had just come aboard.

We dropped down river with the tide, having to wait for some time at Gravesend, where we took on another pilot, who navigated the ship past the Goodwin Sands. Thence, we held a straight course down Channel; and I shall never forget the first three days at sea.

The wind howled without ceasing, the waves tossing the ship hither and thither, as if she were a cork. The gale was blowing south-west, right in our teeth; so that the ship pitched so violently that at times her peak was buried under the waves, the screw racing in the air as if distracted.

MacAndrew and myself were the only passengers on board, the "Westmoreland" being a cargo ship with only four saloon berths. In order to avoid attracting the curiosity of a number of fellow-passengers, MacAndrew had purposely selected the "Westmoreland" on which to book our passages.

I do not think we made more than six knots an hour, until we were half-way across the Bay. Then the wind fell, and the sea became what I believe is known as "choppy." We were followed by a great number of gulls, who circled around the ship, and sometimes even settled upon the masts. Also, nearly every day we were accompanied by a shoal of porpoises; and, as far south as Finisterre, we were seldom out of sight of whales, who frequently came quite near to the ship.

It was when we were steaming down the sunny coast of Portugal, near enough to the land to observe the beauty of the scenery, that MacAndrew came on deck. He had been terribly sea-sick, and his complexion was as green as a cabbage.

He picked up wonderfully, however, as soon as we were in the Mediterranean, where the sea was delightfully calm. He and I and Captain Crouch used to sit on deck of an evening, talking together upon all manner of subjects, the engines throbbing beneath our feet, as the ship steamed towards the Island of Malta.

It must be confessed that MacAndrew and myself never spoke of the object of our journey, in the presence of Captain Crouch. Josephus MacAndrew's notebooks, the papyrus, the map and the scarabaeus itself, were kept in a small brassbound box, which was under the bunk in my cabin. The key of this box I carried upon my watch-chain, which I was in the habit of placing under my pillow before I went to sleep. MacAndrew had a duplicate.

It was the night before we reached Valetta that the first of our calamities befell us. I had gone to bed early, resolved to be up at daybreak the following day. We were due in port at six o'clock; and as we were to be the whole day in Malta, I had resolved to make a journey to the ancient capital of Citta Vecchia.

About midnight, I awoke with a start. I cannot say what disturbed me. I sat up in bed and listened for some moments, but could hear no sound. To assure myself that there was no cause to be alarmed, I placed a hand under my pillow—to discover to my consternation that my watch and bunch of keys were gone.

I immediately got out of bed and, striking a match, lit the oil lamp. In those days, ships of the class of the "Westmoreland" were not fitted with electric light. Going down on my hands and knees, I drew out the brassbound box, in the lock of which I found my bunch of keys. Opening it, I looked inside and discovered at once that the scarabaeus had gone!

OF THE MEETING OF CAPTAIN CROUCH AND MR. WANG

I WENT at once to MacAndrew's cabin, where I found him sound

asleep. A light was burning in the room; and I remember, I stood

regarding him for some minutes, before I ventured to awaken him, I was

struck by the extraordinary aspect of the man, when asleep. His

appearance, as a rule, suggested great vitality and energy; but, with

his eyes closed, he resembled a corpse. His complexion was a most

death-like and ghastly colour, and his long, thin hands, spread out

upon the coverlet, looked delicate and utterly strengthless.

And yet, when I woke him up and told him what had happened, he was like a raging beast. He sprang from his bed and cried out in a voice of thunder that must have been audible from one end of the ship to the other. He was the most violent man I have ever known.

I did my best to calm him, to persuade him to reason the thing out in a sensible manner. But he would not listen to me, until he had dressed in his clothes and gone out upon the deck.

It was then about two o'clock in the morning. A head wind was blowing, which was a trifle cold, especially to me who was but thinly clad. There was a multitude of stars in the sky, beautiful to behold.

For two hours, pacing the deck side by side, myself trying to keep step with the amazingly long strides taken by my companion, we discussed what was best to do. Unquestionably, the thief was upon the ship; and I made no secret to MacAndrew of my suspicions regarding the two men who were on board, who resembled Ancient Egyptians.

There was no use in discussing the fact that we were faced with a terribly serious proposition. It appeared that the existence of the scarabaeus was known to others besides ourselves. It was manifest that we were tracked. Remembering the tragedy that had concluded the lifetime of MacAndrew's uncle, I was filled with the gravest misgivings.

We decided that the crew of the ship must be searched; but this could not be done unless we took Captain Crouch into our counsels. I had been eager to do this from the first, because the captain had already inspired my confidence. But MacAndrew was very reluctant to share our secret with any one, and I fully believe only consented to do so because there was no alternative course of action.

At four o'clock the captain came on deck to take the last watch, and at once expressed surprise at seeing MacAndrew and myself. This gave us our opportunity. We explained that there had been a robbery on board. Crouch went on to the bridge to verify the ship's course, and then conducted us into his cabin, where, in spite of the early hour, he lit one of his atrocious pipes.

We told the whole story, much as it is set down here, disguising nothing. And Crouch listened to every word, puffing silently at his pipe, now and again lifting his eyebrows in surprise, or tugging at the little goat's-beard that he wore upon his chin.

"Well," said he, when the whole story was ended, "I've come across many remarkable things in the course of my life; but, if all this is true, it beats the lot. I don't say it's impossible. I have seen so many strange things, and I myself have passed through so many remarkable adventures, that I am quite ready to believe it. At all events, I will do my best to help you. At four bells the whole crew shall muster, and every man jack of them shall be searched."

We were off the north coast of Malta, and the houses of Valetta were becoming visible in the distance, when Crouch paraded the crew on deck. Every one was searched, their boxes and sea kit-bags opened, the forecastle turned upside down. Every man on board—seaman, stoker, quartermaster or cook—was cross-examined by MacAndrew, who, being a barrister, found himself in his own element. But no information was obtained in regard to the missing scarabaeus. As for the two "Egyptians," they confessed to being natives of a country in the region of the Upper Nile. But they could speak English very imperfectly, and no information could be got out of either of them.

So we came into the port of Valetta and cast anchor. I naturally postponed my journey to Citta Vecchia; whereas MacAndrew remained on deck all that morning, pacing to and fro, like a wild beast in a cage. He realised—as also did I—that without the scarabaeus, our journey was likely to end in failure.

All that day the crew were discharging cargo; and at dinner-time came the second of our disasters. It was discovered, by one of the ship's quartermasters, that both the "Egyptians" had disappeared.

No one had seen them leave the ship. We were not far from the wharf, so that it was not impossible that they had dived overboard and swum ashore. It is more likely, however, that they escaped either in one of the lighters that was taking in cargo, or in one of the small Maltese boats that surrounded the ship.

After dinner, Crouch, MacAndrew and I talked the matter out in the captain's cabin. Captain Crouch was intensely interested in the whole affair. It was he who suggested what we should do, who offered us every means of assistance in his power. He never despaired that we would get back the scarabaeus, and more than once he expressed a wish that he himself was coming with us to the Tomb of Serophis.

Early in the afternoon, Crouch came ashore with us, and we accompanied him to the offices of his company's agent. The agent was a fat man, who looked like an Italian. He shook hands cordially with both MacAndrew and myself.

He mentioned to Captain Crouch that there was upon the island a certain Captain Ferguson, of the "Cumberland," a sister ship to the "Westmoreland." Captain Ferguson had been put ashore, some months before, in a highly critical condition, suffering from malarial fever. He had now been discharged from hospital, and was able to return to duty; but the agent had no instructions regarding him.

Crouch said nothing when he heard this, but seemed to be turning the matter over in his mind, for he nodded his head repeatedly. As soon as we were outside the office, however, he took each of us by an arm, and led us into a small café of the cheaper sort, of the kind patronised by sailors.

There he ordered some tea, which was brought to us. Leaning across the table, and speaking in a voice that was little above a whisper, he unburdened himself as follows:

"Professor," said he, "I am heart and soul in this affair. You must understand that, although I have followed the sea as a calling for a great number of years, I have taken part in many similar expeditions, both in Africa and Asia. I don't wish to be pessimistic, but I think you little realise the dangers of your position. You are, or were, in possession of a valuable relic of antiquity. The possession of that relic, Mr. MacAndrew, cost your uncle his life. It appears that, somehow or other, your secret is out. You have been tracked on board my ship. The scarabaeus has been stolen. You have a journey of several thousand miles before you. You will probably be tracked every mile of the way; and before you come to your destination, there may be an attempt to murder you."

I realised all this. Since twelve o'clock on the previous night I had had little time to think, but already I regretted that I had ever consented to have anything to do with so perilous an enterprise. It was unthinkable that I, a professor of Ancient Egyptian History, a curator of the British Museum, one who had lived the life of a student, or recluse, should find himself seated in a low café, in the poorer part of the town of Valetta, discussing the possibility of being murdered! I felt no confidence in myself. I cannot say that I felt that I could rely upon MacAndrew. It was therefore with a certain feeling of relief that I listened to Captain Crouch's proposal.

"I am interested in this business," he continued. "I would like to see it through. With your permission I will accompany you. I have an idea that I may be of assistance."

To my surprise, MacAndrew pooh-poohed the whole idea. He said that Captain Crouch had exaggerated the danger. He saw no reason why we should add a third member to our expedition.

However, this was one of the occasions on which I made up my mind and stuck to it. I insisted upon Captain Crouch coming with us. I offered to pay all his expenses. I even went so far as to say that if Crouch did not accompany us, I myself would return to England.

MacAndrew was obliged to give way. He did so with reluctance, that was plain to see. But, in the end, he shook hands with Captain Crouch, and in that small café, over our teacups, we agreed to stand by each other through thick and thin. It will be seen to what extent MacAndrew fulfilled his promise.

Crouch returned to the agent's, where he cabled to England, arranging for Captain Ferguson to take over the command of the "Westmoreland," when the ship reached Alexandria. We then went to the police station, and interviewed a Maltese superintendent of police, to whom we endeavoured to explain that the scarabaeus was of priceless value.

That night we three dined together in one of the principal hotels, situated in the Strada Reale, which is the main street that runs the length of the city of Valetta. We were not sailing till the following morning. We had fifteen or sixteen hours therefore in which to find our stolen property; but, to tell the truth, not even Captain Crouch had any idea as to how we were to begin our search.

In the dining-room we found Captain Crouch, reading an English newspaper whilst he was waiting for dinner. That paper contained a full account of the discovery of Ah Jim, a European boy who had been kidnapped by Chinese as a child, and who had finally been discovered through the agency of Mr. Wang, the celebrated Chinese detective.

"That's the man for us," said Captain Crouch, "if we could only get hold of him and afford to pay him. His fees, I believe, are tremendous. I have never seen him, but I have heard a great deal concerning him. They tell me he has never failed."

Now, coincidence, as I have said, is not such a singular thing as many people try to make out. That same evening, whilst waiting in the hall of the hotel for MacAndrew, I had occupied myself by looking at the visitors' book; and I remembered quite well that my attention was attracted by three names in very different handwriting, which followed one after the other. I cannot say why I should remember the first two. But I do.

Sir Julius O'Brien—a strong, firm, but angular handwriting.

The Contessa Maria della Falconara—a neat, little, back-handed calligraphy.

Mr. Wang—in the most amazing scrawl I have ever beheld in my life.

Now, this may seem coincidence: that Captain Crouch should have come across Mr. Wang's name in a newspaper, and that I should have seen it in the visitors' book, within a few minutes of one another. It is not coincidence at all. The paper was an old one. Mr. Wang was a celebrity. When he booked a room in the hotel, his name was recognised by the booking-clerk, who promptly turned up the old newspaper to look for an account of the discovery of Ah Jim. This newspaper he gave to the hall-porter, who gave it to the head-waiter, who left it in the dining-room. In the majority of cases, what is called coincidence can thus easily be accounted for. It may be thus with the scarabaeus.

I at once told Captain Crouch that Mr. Wang was staying in that very hotel. MacAndrew was even more anxious to regain possession of the scarab than Crouch and myself; and it was agreed, then and there, that we should ask Mr. Wang to assist us.

Before we had finished dining, the great detective himself entered the room. Not one of the three of us had ever seen him before, but there was no mistaking his identity. He was dressed in a European flannel suit, and his little pigtail hung down over his collar. He was on his way back to China from England, having solved the Mystery of Ah Jim. He did not strike me as being so fat as I had heard, and his face was more wrinkled than I had supposed. Upon his little, squat nose was a pair of gold-rimmed spectacles. He walked into the room with his hands folded in front of him, and I noticed that on one of his fingers he was wearing a large diamond ring.

At MacAndrew's suggestion, Captain Crouch approached the great detective, and bowed somewhat awkwardly.

"Mr. Wang, I believe?" said he.

"The same, sir," said Wang. "I have not the pleasure."

"My name is Captain Crouch."

"The Captain Crouch?" said Mr. Wang.

"I never heard of another one," said Crouch.

"There is no doubt of it," exclaimed Mr. Wang. "A cork foot, and a glass eye." Then he held out a hand. "Captain Crouch," said he, "pleased to meet you."

They shook hands. That was the meeting of Captain Crouch and Mr. Wang. Strange men, both of them; but masterful and unique.

HOW MR. WANG GOT TO WORK

IT was MacAndrew's intention to tell Mr. Wang only so much as he

considered necessary: namely, that the scarabaeus had been

stolen from my cabin, on board the "Westmoreland," presumedly by the

two "Egyptians" who had deserted from the ship. But we found that it

was impossible to keep the whole truth from the detective. He cross-examined us so acutely, and he wanted to know so many details that we

finally came to the conclusion that it would be best to tell him the

whole story from start to end.

This we did, omitting nothing, from the murder of Josephus MacAndrew to the arrival of the "Westmoreland" in the harbour of Malta. And when I look back upon those preliminary days, I cannot but feel grateful that we told Mr. Wang the truth. Had it not been for him, I am convinced that not one of us would have come out of the business alive.

I have said already that I believed myself to be in the gravest danger. And I could see from the expression on the round, jovial face of Mr. Wang that he, too, regarded the whole matter in a very serious light. Whilst we were telling him the story, he continued to eat his dinner; but no sooner had he finished than he sprang to his foot, crying out that there was no time to lose. We were to wait for him at the hotel, He had certain inquiries to make.

He went out, wearing a straw hat, underneath which he tucked his pigtail, and was absent about an hour and a half. When he returned, he called us together in a corner of the smoking-room, where we sat round a small table with our heads almost touching.