RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

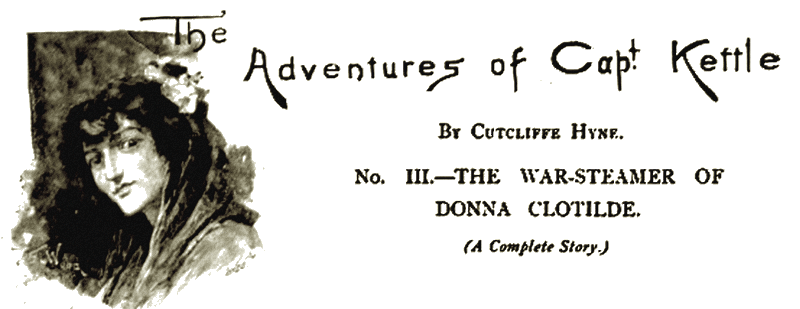

The Adventures of Captain Kettle, 1898,

with "The War-Steamer of Donna Clotilde"

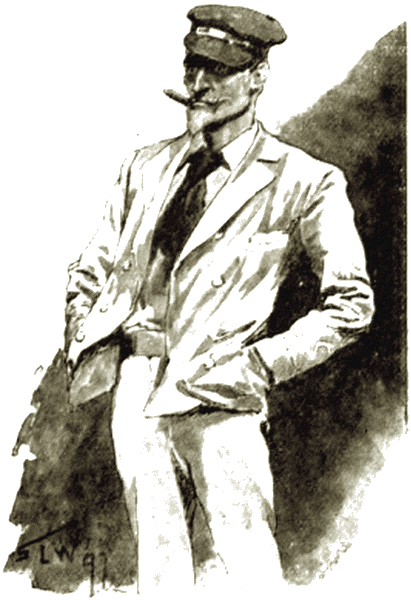

I THINK it may be taken as one of the most remarkable attributes of Captain Owen Kettle that, whatever circumstances might betide, he was always neat and trim in his personal appearance. Even in most affluent hours he had never been able to afford an expensive tailor; indeed, it is much to be doubted if, during all his life, he ever bought a scrap of raiment anywhere except at a ready-made establishment; but in spite of this, his clothes were always conspicuously well- fitting, carried the creases in exactly the right place, and seemed to the critical onlooker to be capable of improvement in no point whatsoever. He looked spruce even in oilskins and thigh boots.

Of course, being a sailor, he was handy with his needle. I have seen him take a white drill jacket, torn to ribands in a rough and tumble with mutinous members his crew, and fine-draw the rents so wonderfully that all traces of the disaster were completely lost. I believe, too, he was capable of taking a roll of material and cutting it out with his knife upon the deck- planks, and fabricating garments ab initio; and though I never actually saw him do this with my own eyes, I did hear that the clothes he appeared in at Valparaiso were so made, and I marvelled at their neatness.

It was just after his disastrous adventure in Cuba; he trod the streets in a state of utter pecuniary destitution; his cheeks were sunk, and his eyes were haggard; but the red torpedo beard was as trim as ever; his cap was spick and span; the white drill clothes with their brass buttons were the usual miracle of perfection; and even his tiny canvas shoes had not so much as a smudge upon their pipe-clay Indeed, in the first instance I think it must have been this spruceness, and nothing else, which made him find favour in the eyes of so fastidious a person as Clotilde La Touche.

But be this as it may, it is a fact that Donna Clotilde just saw the man from her carriage as he walked along the Paseo de Colón, promptly asked his name, and, getting no immediate reply, dispatched one of her admirers there and then to make his acquaintance. The envoy was instructed to find out who he was, and contrive that Donna Clotilde should meet the little sailor at dinner in the Café of the Lion d'Or that very evening.

The dinner was given in the patio of the café where palm fronds filtered the moonbeams, and fireflies competed with the electric lights; and at a moderate computation the cost of the viands would have kept Captain Kettle supplied with his average rations for ten months or a year. He was quite aware of this, and appreciated the entertainment none the worse in consequence. Even the champagne, highly sweetened to suit the South American palate, came most pleasantly to him. He liked champagne according to its lack of dryness, and this was the sweetest wine that had ever passed his lips.

The conversation during that curious meal ran in phases. With the hors d'oeuvres came a course of ordinary civilities; then for a space there rolled out an autobiographical account of some of Kettle's exploits, skilfully and painlessly extracted by Donna Clotilde's naïve questions; and then, with the cognac and cigarettes, a spasm of politics shook the diners like an ague.

Of a sudden one of the men recollected himself, looked to this side and that with a scared face, and rapped the table with his knuckles.

"Ladies," he said imploringly, "and Señores, the heat is great. It may be dangerous.

"Pah!" said Donna Clotilde, "we are talking in English."

"Which other people besides ourselves understand even in Valparaiso."

"Let them listen," said Captain Kettle. "I hold the same opinions on politics as Miss La Touche here, since she has explained to me how things really are, and I don't care who knows that I think the present Government, and the old system, rotten. I am not in the habit of putting my opinions in words, Mr. Silva, and being frightened of people hearing them."

"You," said the cautious man dryly, "have little to lose here, Captain. Donna Clotilde has much. I should be very sorry to read in my morning paper that she had died from apoplexy—the arsenical variety—during the course of the preceding night."

"Pooh," said Kettle, "they could never do that."

"As a resident in Chili," returned Silva, "let me venture to disagree with you, Captain. It is a disease to which the opponents of President Quijarra are regularly addicted whenever they show any marked political activity. The palm trees in this patio have a reputation, too, for being phenomenally long-eared. So, if it pleases you all, suppose we go out on the roof? The moon will afford us a fine prospect—and—the air up there is reputed healthy."

He picked up Donna Clotilde's fan and mantilla. The other two ladies rose to their feet; Donna Clotilde, with a slight frown of reluctance, did the same; and they all moved off towards the stairway Silva laid detaining fingers upon Captain Kettle's arm.

"Captain," he said, "if I may give you a friendly hint, slip away now and go to your quarters."

"I fancy, sir," said Captain Kettle, "that Miss La Touche has employment to offer me."

"If she has," retorted Silva, "which I doubt, it will not be employment you will care about."

"I am what they call here 'on the beach,'" said Kettle, "and I cannot afford to miss chances. I am a married man, Mr. Silva, with children to think about."

"Ah!" the Chilian murmured thoughtfully. "I wonder if she knows he's married? Well, Captain, if you will go up, come along, and I'm sure I wish you luck."

The flat roof of the Café of the Lion d'Or is set out as a garden, with orange trees growing against the parapets, and elephants' ears and other tropical foliage plants stand here and there in round green tubs. Around it are the other roofs of the city, which, with the streets between, look like some white rocky plain cut up by steep canons. A glow comes from these depths below, and with it the blurred hum of people. But nothing articulate gets up to the Lion d'Or, and in the very mistiness of the noise there is something indescribably fascinating.

Moreover, it is a place where the fireflies of Valparaiso most do congregate. Saving for the lamps of heaven, they have no other lighting on that roof. The owners (who are Israelites) pride themselves on this: it gives the garden an air of mystery; it has made it the natural birthplace of plots above numbering; and it has brought them profit almost beyond belief. Your true plotter, when his ecstasy comes upon him, is not the man to be niggardly with the purse. He is alive and glowing then; he may very possibly be dead to-morrow; and in the meanwhile money is useless, and the things that money can buy—and the very best of their sort—are most desirable.

One more whispered hint did Mr. Silva give to Captain Kettle as they made their way together up the white stone steps.

"Do you know who and what our hostess is?" he asked.

"A very nice young lady," replied the mariner promptly, "with a fine taste in suppers."

"She is all that," said Silva; "but she also happens to be the richest woman in Chili. Her father owned mines innumerable, and when he came by his end in our last revolution, he left every dollar he had at Donna Clotilde's entire disposal. By some unfortunate oversight, personal fear has been left out of her composition, and she seems anxious to add it to the list of her acquirements."

Captain Kettle puckered his brows. "I don't seem to understand you," he said.

"I say this," Silva murmured, "because there seems no other way to explain the keenness with which she hunts after personal danger. At present she is intriguing against President Quijarra's Government. Well, we all know that Quijarra is a brigand, just as his predecessor was before him. The man who succeeds him in the Presidency of Chili will be a brigand also. It is the custom of my country. But interfering with brigandage is a ticklish operation, and Quijarra is always scrupulous to wring the necks of any one whom he thinks at all likely to interfere with his peculiar methods."

"I should say that from his point of view," said Kettle, "he was acting quite rightly, sir."

"I thought you'd look at it sensibly," said Silva. "Well, Captain, here we are at the top of the stair. Don't you think you had better change your mind, and slip away now, and go back to your quarters?"

"Why, no, sir," said Captain Kettle. "From what you tell me, it seems possible that Miss La Touche may shortly be seeing trouble, and it would give me pleasure to be near and ready to bear a hand. She is a lady for whom I have got considerable regard. That supper, sir, which we have just eaten, and the wine, are things which will live in my memory."

He stepped out on to the roof, and Donna Clotilde came to meet him. She linked her fingers upon his arm, and led him apart from the rest. At the further angle of the gardens they leant their elbows upon the parapet, and talked, whilst the glow from the street below faintly lit their faces, and the fireflies winked behind their backs.

"I thank you, Captain, for your offer," she said at length, "and I accept it as freely as it was given. I have had proposals of similar service before, but they came from the wrong sort. I wanted a Man, and I found out that you were that before you had been at the dinner-table five minutes."

Captain Kettle bowed to the compliment. "But," said he, "if I am that, I have all of a man's failings."

"I like them better," said the lady, "than a half-man's virtues. And as a proof I offer you command of my navy.

"Your navy, Miss?"

"It has yet to be formed," said Donna Clotilde, "and you must form it. But once we make the nucleus other ships of the existing force will desert to us, and with those we must fight and beat the rest. Once we have the navy, we can bombard the ports into submission till the country thrusts out President Quijarra of its own accord, and sets me up in his place."

"Oh," said Kettle, "I didn't understand. Then you want to be Queen of Chili?"

"President."

"But a President is a man, isn't he?"

"Why? Answer me that."

"Because—well, because they always have been, Miss."

"Because men up to now have always taken the best things to themselves. Well, Captain, all that is changing; the world is moving on; and women are forcing their way in, and taking their proper place. You say that no State has yet had a woman- president. You are quite right. I shall be the first."

Captain Kettle frowned a little, and looked thoughtfully down into the lighted street beneath. But presently he made up his mind, and spoke again.

"I'll accept your offer, Miss, to command the navy, and I'll do the work well. You may rely on that. Although I say it myself, you'd find it hard to get a better man. I know the kind of brutes one has to ship as seamen along this South American coast, and I'm the sort of brute to handle them. By James! yes, and you shall see me make them do most things, short of miracles.

"But there's one other thing, Miss, I ought to say, and I must apologise for mentioning it, seeing that you're not a business person, I must have my twelve pound a month, and all found. I know it's a lot, and I know you'll tell me wages are down just now. But I couldn't do it for less, Miss. Commanding a navy's a strong order and, besides, there's considerable risk to be counted in as well."

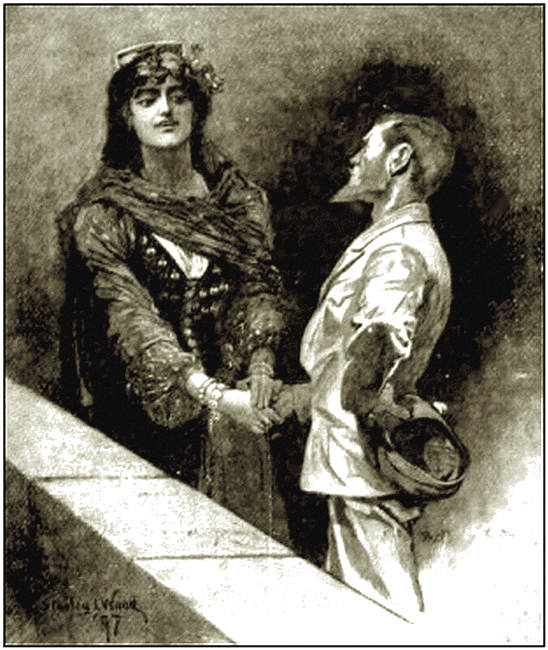

Donna Clotilde took his hand in both hers.

Donna Clotilde took his hand in both hers.

"I thank you, Captain," she said, "for your offer, and I begin to see success ahead from this moment. You need have no fear on the question of remuneration."

"I hope you didn't mind my mentioning it," said Kettle nervously. "I know it's not a thing generally spoken of to ladies. But you see, Miss, I'm a poor man, and feel the need of money sometimes. Of course, twelve pound a month is high, but—"

"My dear Captain," the lady broke in, "what you ask is moderation itself; and, believe me, I respect you for it, and will not forget. Knowing who I am, no other man in Chili would have hesitated to ask"—she had on her tongue to say "a hundred times as much," but suppressed that and said—"more. But in the meantime," said she, "will you accept this hundred- pound note for any current expenses which may occur to you?"

A little old green-painted barque lay hove-to under sail, disseminating the scent of guano through the sweet tropical day. Under her square counter the name El Almirante Cochrane appeared in clean, white lettering. The long South Pacific swells lifted her lazily from hill to valley of the blue water, to the accompaniment of squealing gear and a certain groaning of fabric. The Chilian coast lay afar off, as a white feathery line against one fragment of the sea-rim.

The green-painted barque was old. For many a weary year had she carried guano from rainless Chilian islands to the ports of Europe; and though none of that unsavoury cargo at present festered beneath her hatches, though, indeed, she was in shingle ballast, and had her holds scrubbed down and fitted with bunks for men, the aroma of it had entered into the very soul of her fabric, and not all the washings of the sea could remove it.

A white whaleboat lay astern, riding to a grass-rope painter, and Señor Carlos Silva, whom the whaleboat had brought off from the Chilian beach, sat in the barque's deckhouse talking to Captain Kettle.

"The Señorita will be very disappointed," said Silva.

"I can imagine her disappointment," returned the sailor. "I can measure it by my own. I can tell you, sir, when I saw this filthy, stinking old windjammer waiting for me in Callao, I could have sat down right where I was and cried. I'd got my men together, and I guess I'd talked big about El Almirante Cochrane, the fine new armoured cruiser we were to do wonders in. The only thing I knew about her was her name, but Miss La Touche had promised me the finest ship that could be got, and I only described what I thought a really fine ship would be. And then, when the agent stuck out his finger and pointed out this foul old violet-bed, I tell you it was a bit of a let down."

"There's been some desperate robbery somewhere," said Silva.

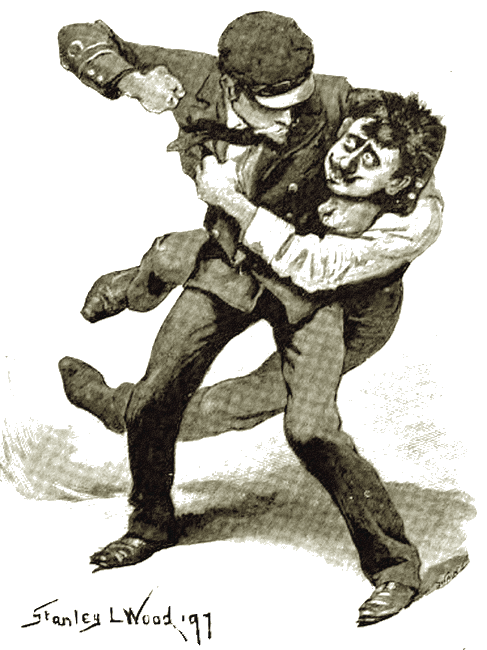

"It didn't take me long to guess that," said Kettle, "and I concluded the agent was the thief, and started in to take it out of him without further talk. He hadn't a pistol, so I only used my hands to him, but I guess I fingered him enough in three minutes to stop his dancing for another month. He swore by all the saints he was innocent, and that he was only the tool of other men; and perhaps that was so. But he deserved what he got for being in such shady employment."

I fingered him enough in three minutes to stop his dancing for another month.

"Still, that didn't procure you another ship?"

"Hammering the agent couldn't make him do an impossibility, sir. There wasn't such a vessel as I wanted in all the ports of Peru. So I just took this nosegay that was offered, lured my crew aboard, and put out past San Lorenzo island, and got to sea. It's a bit of a come down, sir, for a steamer-sailor like me," the little man added with a sigh, "to put an old wind-jammer through her gymnastics again. I thought I'd done with 'main-sail haul' and raw hide chafing gear, and all the white wings nonsense for good and always."

"But, Captain, what did you come out for? What earthly good can you do with an old wreck like this?"

"Why, sir, I shall carry out what was arranged with La Touche. I shall come up with one of President Quijarra's Government vessels, capture her, and then start in to collar the rest. There's no alteration in the programme. It's only made more difficult, that's all."

"I rowed out here to the rendezvous to tell you the Cancelario is at moorings in Tampique Bay, and that the Señorita would like to see you make your beginning upon her. But what's the good of that news, now? The Cancelario is a fine new warship of 3,000 tons. She's fitted with everything modern in guns and machinery; she's three hundred men of a crew, and she lays always with steam up and an armed watch set. To go near her in this clumsy little barque would be to make yourself a laughing-stock. Why, your English Cochrane wouldn't have done it."

"I know nothing about Lord Cochrane, Mr. Silva. He was dead before my time but whatever people may have done to him, I can tell any one who cares to hear, that the man who's talking to you now is a bit of an awkward handful to laugh at. No, sir, I expect there'll be trouble over it, but you may tell Miss La Touche we shall have the Cancelario, if she'll stay in Tampique Bay till I can drive this old lavender box up to her."

For a minute Silva stared in silent wonder. "Then, Captain," said he, "all I can think is, you must have enormous trust in your crew."

Captain Kettle bit the end from a fresh cigar. "You should go and look at them for yourself," said he, "and hear their talk, and then you'd know. The beasts are fit to eat me already."

"How did you get them on board?"

"Well, you see, sir, I collected them by promises—fine pay, fine ship, fine cruise, fine chances, and so on; and when I'd only this smelling bottle here to show them, they hung back a bit. If there'd been only twenty of them, I don't say but what I could have hustled them on board with a gun and some ugly words. But sixty were too many to tackle; so I just said to them that El Almirante Cochrane was only a ferry to take us across to a fine war steamer that was lying out of sight elsewhere; and they swallowed the yarn, and stepped in over the side.

"I can't say they've behaved like lambs since. The grub's not been to their fancy, and I must say the biscuit was crawling; and it seems that, as a bedroom, the hold hurt their delicate noses; and, between one thing and another, I've had to shoot six of them before they understood I was skipper here. You see, sir, they were most of them living in Callao before they shipped, because there's no extradition there; and so they're rather a toughish crowd to handle."

"What a horrible time you must have had!"

"There has been no kid-glove work for me, sir, since I got to sea with this rose garden; and I must say it would have knocked the poetry right out of most men. But, personally, I can't say it has done that to me you'd hardly believe it, sir, but once or twice, when the whole lot of the brutes have been raging against me, I've been very nearly happy. And afterwards, when I've got a spell of rest, I've picked up pen and paper, and knocked off one or two of the prettiest sonnets a man could wish to see in print. If you like, sir, I'll read you a couple before you go back to your whale-boat."

"I thank you, skipper, but not now. Time is on the move, and Donna Clotilde is waiting for me. What am I to tell her?"

"Say, of course, that her orders are being carried out, and her pay being earned."

"My poor fellow," said Silva, with a sudden gush of remorse, "you are only sacrificing yourself uselessly. What can you, in a small sailing vessel like this, do with your rifles against a splendidly armed vessel like the Cancelario?"

"Not much in the shooting line, that's certain," said Kettle, cheerfully. "That beautiful agent sold us even over the ammunition. There were kegs put on board marked 'cartridges,' but when I came to break one or two so as to serve out a little ammunition, for practice be hanged if the kegs weren't full of powder. And it wasn't the stuff for guns even; it was blasting powder, same as they use in the mines. Oh, sir, that agent was the holiest kind of fraud."

Silva wrung his hands. "Captain," he cried, "you must not go on with this mad cruise. It would be sheer suicide for you to find the Cancelario."

"You shall give me news of it again after I've met her," said Captain Kettle. "For the present, sir, I follow out Miss La Touche's orders, and earn my £12 a month. But if you're my friend, Mr. Silva, and want to do me a good turn, you might hint that, if things go well, I could do with a rise to £14 a month when I'm sailing the Cancelario for her."

The outline of Tampique Bay stood out clearly in bright moonshine, and the sea down the path of the moon's rays showed a canal of silver, cut through rolling fields of purple. The green- painted barque was heading into the bay on the port tack; and at moorings, before the town, in the curve of the shore, the grotesque spars of a modern warship showed in black silhouette against the moonbeams. A slate-coloured naphtha-launch was sliding out over the swells towards the barque.

Captain Kettle came up from below, and watched the naphtha- launch with throbbing interest. He had hatched a scheme for capturing the Cancelario, and had made his preparations; and here was an interruption coming which might very well upset anything most ruinously. Nor was he alone in his regard. The barque's topgallant rail was lined with faces; all her complement were wondering who these folk might be who were so confidently coming out to meet them.

A Jacob's ladder was thrown over the side; the slate-coloured launch swept up, and emitted—a woman. Captain Kettle started, and went down into the waist to meet her. A minute later he was wondering whether he dreamed, or whether he was really walking his quarter deck in company with Donna Clotilde La Touche. But meanwhile the barque held steadily along her course.

The talk between them was not for long.

"I must beseech you, Miss, to go back from where you came," said Kettle. "You must trust me to carry out this business without your supervision."

"Is your method very dangerous?" she asked.

"I couldn't recommend it to an Insurance Company," said Kettle, thoughtfully.

"Tell me your scheme."

Kettle did so in some forty words. He was pithy, and Donna Clotilde was cool. She heard him without change of colour.

"Ah," she said, "I think you will do it."

"You will know one way or another within an hour from now, Miss. But I must ask you to take your launch to a distance. As I tell you, I have made all my own boats so that they won't swim; but, if your little craft was handy, my crew would jump overboard and risk the sharks, and try to reach her in spite of all I could do to stop them. They won't be anxious to fight that Cancelario when the time comes, if there's any way of wriggling out of it."

"You are quite right, Captain; the launch must go; only I do not. I must be your guest here till you can put me on the Cancelario."

Captain Kettle frowned. "What's coming is no job for a woman to be in at, Miss."

"You must leave me to my own opinion about that. You see, we differ upon what a woman should do, Captain. You say a woman should not be president of a republic; you think a woman should not be sharer in a fight; I am going to show you how a woman can be both." She leant her shoulders over the rail, and hailed the naphtha-launch with a sharp command. A man in the bows cast off the line with which it towed; the man aft put over his tiller, and set the engines a-going; and, like a slim, grey ghost, the launch slid quietly away into the gloom. "You see," she said, "I'm bound to stay with you now," and she looked upon him with a burning glance.

But Kettle replied coldly. "You are my owner, Miss," he said, "and can do as you wish. It is not for me now to say that you are foolish. Do I understand you still wish me to carry out my original plan?"

"Yes," she said curtly.

"Very well, Miss, then we shall be aboard of that war-steamer in less than fifteen minutes." He bade his second mate call aft the crew; but instead of remaining to meet them, he took a keen glance at the barque's canvas, another at her wake, another at the moored cruiser ahead, and then, after peering thoughtfully at the clouds which sailed in the sky, he went to the companion-way and dived below. The crew trooped aft and stood at the break of the quarterdeck, waiting for him. And in the meanwhile they feasted their eyes with many different thoughts on Donna Clotilde La Touche.

Presently Captain Kettle returned to deck, aggressive and cheerful, and faced the men with hands in his jacket pockets. Each pocket bulged with something heavy, and the men, who by this time had come to understand Captain Kettle's ways, began to grow quiet and nervous. He came to the point without any showy oratory.

Captain Kettle faced the men with hands in his jacket pockets.

"Now, my lads," said he, "I told you when you shipped aboard this lavender-box in Callao, that she was merely a ferry to carry you to a fine war-steamer which was lying elsewhere. Well, there's the steamer, just off the starboard bow yonder. Her name's the Cancelario, and at present she seems to belong to President Quijarra's Government. But Miss La Touche here (who is employing both me and you, just for the present) intends to set up a Government of her own; and, as a preliminary, she wants that ship. We've to grab it for her."

Captain Kettle broke off, and for a full minute there was silence. Then some one amongst the men laughed, and a dozen others joined in.

"That's right," said Kettle. "Cackle away, you scum. You'd be singing a different tune if you knew what was beneath you."

A voice from the gloom—an educated voice—answered him. "Don't be foolish, skipper. We're not going to ram our heads against a brick wall like that. We set some value on our lives."

"Do you?" said Kettle. "Then pray that this breeze doesn't drop (as it seems likely to do) or you'll lose them. Shall I tell you what I was up to below just now? You remember those kegs of blasting powder? Well, they're in the lazaret, where some of you stowed them; but they're all of them unheaded, and one of them carries the end of a fuse. That fuse is cut to burn just twenty minutes, and the end's lighted.

"Wait a bit. It's no use going to try and douse it. There's a pistol fixed to the lazaret hatch, and if you try to lift it that pistol will shoot into the powder, and we'll all go up together without further palaver. Steady, now, there, and hear me out. You can't lower away boats, and get clear that way. The boat's bottoms will tumble away so soon as you try to hoist them off the skids. I saw to that last night. And you can't require any telling to know there are far too many sharks about to make a swim healthy exercise."

The men began to rustle and talk.

"Now, don't spoil your only chance," said Kettle, "by singing out. If on the cruiser yonder they think there's anything wrong, they'll run out a gun or two, and blow us out of the water before we can come near them. I've got no arms to give you; but you have your knives, and I guess you shouldn't want more. Get in the shadow of the rail there, and keep hid till you hear her bump. Then jump on board, knock everybody you see over the side, and keep the rest below."

"They'll see us coming," whimpered a voice. "They'll never let us board."

"They'll hear us," the Captain retorted, "if you gallows- ornaments bellow like that, and then all we'll have to do will be to sit tight where we are till that powder blows us like a thin kind of spray up against the stars. Now, get to cover with you, all hands, and not another sound. It's your only chance."

The men crept away, shaking, and Captain Kettle himself took the wheel, and appeared to drowse over it. He gave her half a spoke at a time, and by invisible degrees the barque fell off till she headed dead on for the cruiser. Save for the faint creaking of her gear, no sound came from her, and she slunk on through the night like some patched and tattered phantom. Far down in her lazaret the glowing end of the fuse crept nearer to the powder barrels, and in imagination every mind on board was following its race.

Nearer and nearer she drew to the Cancelario, and ever nearer. The waiting men felt as though the hearts of them would leap from their breasts. Two of them fainted. Then came a hail from the cruiser: "Barque, ahoy, are you all asleep there?"

Captain Kettle drowsed on over the wheel. Donna Clotilde, from the shadow of the house, could see him nodding like a man in deep sleep.

"Carrajo! you barque, there! Put down your helm. You'll be aboard of us in a minute."

Kettle made no reply: his hands sawed automatically at the spokes, and the glow from the binnacle fell upon close, shut eyes. It was a fine bit of acting.

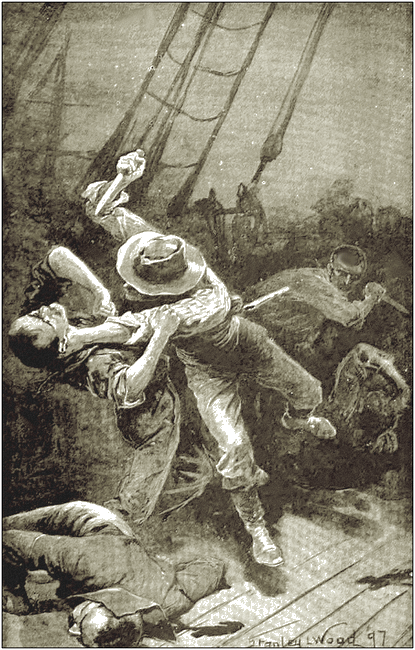

The Chilians shouted but they could not prevent the collision, and when it came, there broke out a yell as though the gates of the Pit had been suddenly unlocked.

The barque's crew of human refuse, mad with terror, rose up in a flock from behind the bulwarks. As one man they clambered over the cruiser's side and spread about her decks.

Ill provided with weapons though they might be, the Chilians were scarcely better armed. A sentry squibbed off his rifle, but that was the only shot fired. Knives did the greater part of the work, knives and belaying-pins, and whatever else came to hand. Those of the watch on deck who did not run below were cleared into the sea; the berth deck was stormed; and the waking men surrendered to the pistol nose.

Knives did the greater part of the work.

A couple of desperate fellows went below, and cowed the fireman and engineer on watch. The mooring was slipped, steam was given to the engines, and whilst her former crew were being drafted down into an empty hold, the Cancelario was standing out at a sixteen-knot speed towards the open sea under full command of the raiders. Then from behind them came the roar of an explosion and a spurt of dazzling light, and the men shuddered to think of what they had so narrowly missed. And as it was, some smelling fragments of the old guano barque lit upon the after deck, as they fell headlong from the dark sky above.

Donna Clotilde went on to the upper bridge, and took Captain Kettle by the hand.

"My friend," she said, "I shall never forget this." And she looked at him with eyes that spoke of more than admiration for his success.

"I am earning my pay," said Kettle.

"Pah!" she said, "don't let money come between us. I cannot bear to think of you in connection with sordid things like that. I put you on a higher plane. Captain," she said, and turned her head away, "I shall choose a man like you for my husband."

"Heaven mend your taste, Miss," said Kettle; "but—there may be others like me."

"There are not."

"Then you must be content with the nearest you can get."

Donna Clotilde stamped her foot upon the planking of the bridge.

"You are dull," she cried.

"No," he said, "I have got clear sight, Miss. Won't you go below now and get a spell of sleep? Or will you give me your orders first?"

"No," she answered, "I will not. We must settle this matter first. You have a wife in England, I know, but that is nothing. Divorce is simple here. I have influence with the Church; you could be set free in a day. Am I not the woman you would choose?"

"Miss La Touche, you are my employer."

"Answer my question."

"Then, Miss, if you will have it, you are not."

"But why? Why? Give me your reasons? You are brave. Surely I have shown courage too? Surely you must admire that?"

"I like men for men's work, Miss."

"But that is an exploded notion. Women have got to take their place. They must show themselves the equals of men in everything."

"But you see, Miss," said Kettle, "I prefer to be linked to a lady who is my superior—as I am linked at present. If it pleases you, we had better end this talk."

"No," said Donna Clotilde, "it has got to be settled one way or the other. You know what I want. Marry me as soon as you are set free, and there shall be no end of your power. I will make you rich; I will make you famous. Chili shall be at our feet; the world shall bow to us."

"It could be done," said Kettle with a sigh.

"Then marry me."

"With due respect, I will not," said the little man.

"You know you are speaking to a woman who is not accustomed to be thwarted?"

Captain Kettle bowed.

"Then you will either do as I wish, or leave this ship. I give you an hour to consider it in."

"You will find my second mate the best navigating officer left," said Kettle, and Donna Clotilde, without further words, left the bridge.

The little shipmaster waited for a decent interval, and then sighed, and gave orders. The men on deck obeyed him with quickness. A pair of boat davits were swung out-board, and the boat plentifully victualled and its water-breakers filled. The Cancelario's engines were stopped, and the tackles screamed as the boat was lowered to the water, and rode there at the end of its painter. Captain Kettle left the bridge in charge of his first officer, and went below. He found the lady sitting in the commander's cabin, with head pillowed upon her arms.

"You still wish me to go, Miss?" he said.

"If you will not accept what is offered."

"I am sorry," said the little sailor, "very sorry. If I'd met you, Miss, before I saw Mrs. Kettle, and if you'd been a bit different, I believe I could have liked you. But as it is—"

She leapt to her feet, with eyes that blazed.

"Go!" she cried. "Go, or I will call upon some of those fellows to shoot you."

"Go!" she cried.

"They will do it cheerfully, if you ask them," said Kettle, and did not budge.

She sank down on the sofa again with a wail.

"Oh, go," she cried. "If you are a man, go, and never let me see you again."

Captain Kettle bowed, and went on deck.

A little later he was alone in the quarter-boat. The Cancelario was drawing fast away from him into the night, and the boat danced in the cream of her wake.

"Ah, well," he said to himself, "there's another good chance gone for good and always. What a cantankerous beggar I am." And then for a moment his thoughts went elsewhere, and he got out paper and a stump of pencil, and busily scribbled an elegy to some poppies in a cornfield. The lines had just flitted gracefully across his mind, and they seemed far too comely to be allowed a chance of escape. It was a movement characteristic of his queerly ordered brain. After the more ugly moments of his life, Captain Owen Kettle always turned to the making of verse as an instinctive relief.