RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

The Adventures of Captain Kettle, 1898,

with "The Escape"

"YOU'VE struck the wrong man," said Captain Kettle. "I'm most kinds of idiot, but I'm not the sort to go ramming my head against the French Government for the mere sport of the thing."

"I was told," said Carnegie wearily, "that you were a man that feared nothing on this earth, or I would not have asked you to call upon me."

"You were told right," said Kettle. "But those that spoke about me should have added that I'm not a man who'll take a ticket to land myself in an ugly mess unless someone pays my train fare, and gives me something to spend at the other end. I'm a sailor, sir, by trade or profession, whichever you like to name it, and on a steamboat, when a row has been started, I'll not say but what I've seen it through more than once out of sheer delight in wrestling with an ugly scrape. Yes, sir, that's the kind of brute I am at sea.

"But what you propose is different; it's out of my line; it's gaol-breaking, no less; with a spell of seven years in the jug, if I don't succeed, and no kind of credit to wear, or dollars to jingle, if I do carry it through as you wish. And may I ask, sir, why I should interest myself in this Mr. Clare? I never heard of him till I came in this room half an hour ago in answer to your advertisement."

"He is unjustly condemned," Carnegie repeated, as though he were quoting from a lesson. "He is suffering imprisonment in this pestilential place—er—Cayenne, for a fault which some one else has committed; and unless he is rescued he will die there horribly. I am appealing to your humanity, Captain. Would you see a fellow-countryman wronged?"

"I have only to look in the glass for that," retorted Kettle. "Most people's kicks come to me when I am anywhere within hail. And you'll kindly observe, sir, that I have nothing but your bare word to go on for Mr. Clare's innocence. The French Courts and the French people, by your own admitting, took a very different view of the matter. They said with clearness that he did sell those plans of fortresses to the Germans, and, knowing their way of looking at such a matter, it only surprises me he wasn't guillotined out of hand."

"It is my daughter who is sure of his guiltlessness in the matter," said Carnegie with a flush. "And," he added, "I may say that she is the chief person who wishes for his escape."

Captain Kettle bowed, and fingered the tarnished badge on his cap. He had a chivalrous respect for the other sex.

"And it was she who made me advertise vaguely for a seafaring man who had got daring and the skill to carry out so delicate a matter. We had two hundred answers in four posts: can you credit such a thing?"

"Easily," said Kettle. "I am not the only poor devil of a skipper who's out of a job. But a hundred pounds is not enough, and that's the beginning and the end of it. There's two ways of doing this business, I guess, and one of them's fighting, and the other's bribery. Well, sir, a man can't collect much of an army for twenty five-pun' notes; and as for bribery, why it's hardly enough to buy up a deputy Customs inspector in the ordinary way of business, let alone a whole squad of Cayenne warders with a big idea of their own value and importance.

"Then there's getting out to French Guiana, and getting back, and steamer fare for the pair of us would come to more than a couple of postage stamps. And then where do I come in? You say I can pocket the balance. But I'm hanged if I see where the balance is going to be squeezed from. No, sir; a hundred pounds is mere foolishness, and the kindest thing I can do is to go away without further talk. By James! sir, I can say that if you'd given me this precious scheme as your own, there's a man in this room who would have had a smashed face for his impudence; but, as you tell me there's a lady in the case, I'll say no more."

Captain Kettle stood up, thrust out his chin aggressively, and swung on his cap. Then he took it off again, and coughed with politeness. The door opened, and the girl they had been speaking about came into the room. She stepped quickly across and took his hand.

"Captain Kettle," she said, "I could not leave you alone with my father any longer. I just had to come in and thank you for myself. I knew you would be the man to help us in our trouble. I knew it from your letter."

The little sailor coughed again, and reddened slightly under the tan. "I'm afraid, miss," he said, "I am useless. As I was explaining to your—Mr. Carnegie, before you came in, the job is a bit outside my weight. You see, when I answered that advertisement, I thought it was something with a steamboat that was wanted, and for that sort of thing, with any kind of crew that signs on, I am fitted and no man better. But this—"

"Oh, do not say it is beyond you. Other prisoners have escaped from the French penal settlements. It only requires a strong, determined man to arrange matters from the outside, and the thing is done."

Kettle fidgeted with the badge on his cap. "With respect, miss," said he, "what any other man could do, I would not shy at; but the thing you've got here's impossible; and the gentleman will just have to stay where he is and serve out the time he's earned."

"But, sir," the girl broke out passionately, "he has not earned it. He was accused unjustly. He was condemned as a scapegoat to shield others. They were powerful—he was without interest; and all France was shrieking for a victim. Mr. Clare was a subordinate in a Government office through which these plans of fortresses had passed. He was by birth half an Englishman, and so it was very easy to raise suspicion against him. They forged great sheaves of evidence; they drew off attention from the real thieves; they shamed him horribly; and then they sent him off to those awful Isles de Salut for life. Yes, for life—till age or the diseases of the place should free him by death. Can you think of anything more frightful?"

"Mr. Clare is fortunate in having such a friend."

"A friend!" she repeated. "Has not my father told you? I am his promised wife. Fancy the irony of it? We were to have been married the very day he was condemned. It was my money and my father's which defended him at the trial, and it nearly beggared us. And now I will spend the last penny I can touch to get him free again."

Captain Kettle coughed once more. "It was upon a question of money that Mr. Carnegie and I split, miss. I said to him a hundred pounds would not work it, and there's the naked truth."

"But it must," she cried; "it must! You think us mean—niggardly. But it is not that; we can raise no more. We are at the end of our funds. Look around at this room; does this look like riches?"

It did not. They were in a grimy Newcastle lodging, au troisième, and at one side of the room the flank of a bedstead showed itself in outline against a curtain. The paper was torn and the carpet was absent, and from the shaft of the stairway came that mingled scent of clothes and fried onion which is native to this type of dwelling.

Carnegie himself was a faded man of fifty. His daughter carried the recent traces of beauty, but anxiety had lined her face, and the pinch of res augustae had frayed her gown. All went to advertise the truth of what the girl had been saying, and Kettle's heart warmed towards her. He knew right well the nip of poverty himself. But still, he did not see his way to perform impossibilities, and he lifted up his voice and said so with glum frankness.

"I am not remembering for a minute, miss," he explained, "that I am a fellow with a wife and children dependent on my earnings; I am looking at the matter as though I might be Mr. Clare's relative, and I have got nothing new to tell you. A hundred pounds will not do it, and that is the end of the matter."

The girl wrung her hands, and looked pitifully across at her father.

"Well," said Carnegie with a heavy sigh, "I will scrape up a hundred and twenty, though that will force us to go hungry. And that is final, Captain. If my own neck depended upon it, I could not lay hands on more."

Captain Owen Kettle's face wore a look of pain. He was a man of chivalrous instincts; it irked him to disoblige a lady; but the means they offered him were so terribly insufficient. He did not repeat his refusal aloud, but his face spoke with eloquent sympathy.

The girl sank into one of the shabby chairs despairingly. "If you fail me, sir," she said, "then I have no hope."

Kettle turned away, still fingering the tarnished badge on his cap, and stared drearily through the dingy window panes. A silence filled the room. Carnegie broke it.

"Other men answered the advertisement," he suggested.

"I know they did," his daughter said; "and I read their letters, and I read Captain Kettle's, and if there is one man who could help us out of all those that answered, he is here now in this room. My heart went out to him at once when I saw his application. I have never heard of him before, but, when I read the few pages he sent, it came to me that I knew him intimately from then onwards, and that he and no other in all the world could do the service which we want. Sir," she said, addressing the little sailor directly, "I learnt from that letter that you made poetry, and I felt that the romance of this matter would carry you on where any other man with merely commercial instincts would fail."

"Then you like poetry, miss?"

"I write it," she said, "for the magazines, and sometimes it gets into print."

"Would you mind shaking hands with me?" asked Captain Kettle.

"I want to do so," she answered, "if you will let that mean the signing of our contract."

Captain Kettle held out his fist. "Put it there, miss," said he. "The French Government is a lumping big concern, but I've bucked against a Government before and come out top side, and, by James! I'll do it again. You stay at home, miss, and write poetry, and get the magazines to print it, instead of those rotten adventure yarns they're so fond of, and you'll be doing Great Britain a large service. What the people in this country need is nice rural poetry to tell them what sunsets are like, and how corn grows, and all that, and not cut-throat stories they might fill out for themselves from the morning newspapers if they only knew the men and the ground.

"If I can only know you're at home here, miss, doing that, I can set about this other matter with a cheerful heart I don't think the money will be of much good; but you may trust me to get out to French Guiana somehow, even if I have to work my way there before the mast; and I'll collar hold of Mr. Clare for you and deliver him on board a British ship in the best repair which circumstances will permit. You mustn't expect me to do impossibilities, miss; but I'm working now for a lady who writes poetry for the magazines, and you'll see me go that near to them you'll probably be astonished."

Turn now to another scene. There is a certain turtle-backed isle in the Caribbean Sea sufficiently small and naked to be nameless on the charts. The Admiralty hydrographers mark it merely by a tiny black dot; the American chart-maker has gone further and branded it as "shoal," which seems to hint (and quite incorrectly) that there is water over it at least during spring tides.

The patch of land, which is egg-shaped, measures some 180 yards across its longer diameter, and, although no green seas can roll across its face, it is sufficiently low in the water for the spindrift to whip every inch of its surface during even the mildest of gales. On these occasions the wind lifts great layers of sand from off the roof of the isle, but ever the sea spews up more sand against the beaches; and so the bulk of the place remains a constant quantity, although the material whereof it is built is no two months the same.

As a residence the place is singularly undesirable, and it is probable that, until Captain Owen Kettle scraped for himself a shelter-trench in the middle of the turtle back of sand, the isle has been left severely alone by man throughout all the centuries.

Still human breath was hourly drawn in the immediate neighbourhood, and when the airs blew towards the isle, or the breezes lay stagnant, sharp human cries fell dimly on Kettle's ear to tell him that men near at hand were alive, and awake, and plying their appointed occupations. The larger wooded island, which lay a long rifle shot away, was part of the French penal settlement of Cayenne; and the cries were the higher notes of its tragic opera. But they affected Captain Kettle not at all. He was there on business; he had been at much pains to arrive at his present situation, and had earned a bullet sear across the temple during the process; and, as some time was to elapse before his next move became due, he was filling up the intervening hours by the absorbing pursuit of literature.

He squatted on the floor of his sandpit, with his teeth set in the butt of a cold cigar, and rapped out the lines of sonnets, and transferred them to a sheet of sea-stained paper. He used the stubby bullet of a revolver cartridge from lack of more refined pencil, and his muse worked with lusty pace—as, indeed, it was always wont to do when the world went more than usually awry with him.

He squatted on the floor of his sandpit and rapped out the lines of sonnets.

To even catalogue the little scamp's adventures since his parting with Miss Carnegie in the Tyneside lodging, would be to write a lengthy book; and they are omitted here in toto, because to detail them would of necessity compromise worthy men, both French and English, who do not wish their traffic with Kettle to be publicly advertised.

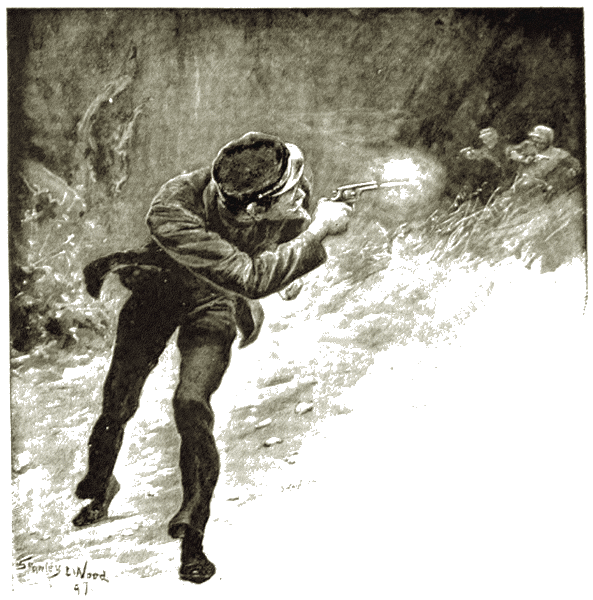

Suffice it to say, then, that he made his way out to French Guiana by ways best known to himself; pervaded Cayenne under an alias, which the local gendarmerie laid bare; exchanged pistol shots with those in authority to avoid arrest; and, in fact, put the entire penal colony, from the governor down to the meanest convict, into a fever of unrest entirely on his especial behalf.

He exchanged pistol shots with those in authority.

He was put to making temporary head-quarters in a mangrove swamp, and completing his preparations from there, and, to say the least of it, matters went hardly with him. But at last he got his preliminaries settled, and left his bivouac among the maddening mosquitoes, and the slime, and the snaky tree roots, and took to the seas again in a lugsail boat, which he annexed by force of arms from its four original owners.

A cold minded person might say that the taking of that boat was an act of glaring piracy; but Kettle told himself that, so far as the French of Cayenne were concerned, he was a "recognised belligerent," and so all the manoeuvres of war were candidly open to him. He had no more qualms in capturing that lugsail boat from a superior force than Nelson once had about taking large ships from the French in the Bay of Aboukir.

He had a depôt of tinned meats cached by one of his agents up a mangrove creek, and under cover of night he sailed up and got these on board, and built them in tightly under the thwarts of his boat so that they would not shift in the seaway. And finally, again cloaked by friendly darkness, he ran on to the beach of the turtle-backed isle, hid his boat in a gully of the sand, scooped out a personal residence where he would be visible only to God and the sea-fowl and sat himself down to wait for an appointed hour.

By day the sun grilled him, by night the sea mists drenched him to the skin, and at times gales lifted the surface from the Caribbean and sent it whistling across the roof of the isle in volleys of stinging spindrift. Moreover, he was constantly pestered by that local ailment, chills-and-fever, partly as a result of two or three trifling wounds bestowed by the gendarmerie, and partly as payment for residence in the miasmatic mangrove swamps; so that, on the whole, life was not very tolerable to him, and he might have been pardoned had he cursed Miss Carnegie for sending him on so troublesome an errand. But he did not do this. He remembered that she was occupying herself at home in Newcastle with the creation of poetry for the British magazines according to their agreement, and he forgot his discomforts in the glow of a Maecenas. It was the first time he had been a bona fide patron of letters, and the pleasure of it intoxicated him.

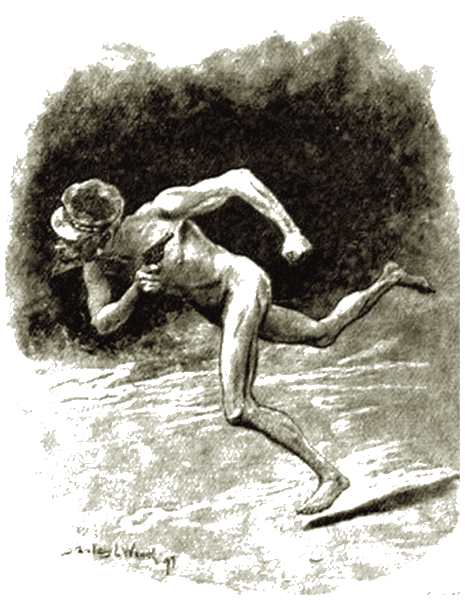

A fortnight passed by—he had given Clare a fortnight in the message he smuggled into the convict station for him to make certain preparations—and at the end of that space of time Captain Kettle rolled his MS. inside an oilskin cover, and addressed it to Miss Carnegie—in case of accidents. He put on the top of his cap, slipped his revolver into these, and put the cap on his head; and then, stripping to the buff, he left his form and got up on to the sand, and walked down its milk-warm surface to the water's edge.

The ripples rang like a million of the tiniest bells upon the fine shingle, and the stars in the velvet night above were reflected in the water. It was far too still a night for his purpose—far too dangerously clear. He would have preferred rain, or even half a gale of wind. But he had fixed his appointment, and he was not the man to let any detail of added danger make him break a tryst. So he waded down into the lonely sea, and struck out at a steady breast stroke for the Isle de Salut, which loomed in low black outline across the waters before him.

A more hazardous business than this part of the man's expedition it would be hard to conceive. There were no prisoners in the world more jealously guarded than those in the pestilential settlement ahead of him. They were forgers, murderers, or what the French hate still more, traitors and foreign spies; and once they stepped ashore upon the beach they were there for always. They were all life-sentence men. Until ferocious labour or the batterings of the climate sent them to rest below the soil, they were doomed to pain with every breath they drew.

Desperate gaoling like this makes desperate men, and did any of the prisoners—even the most cowardly of them—see the glimmer of a chance to escape, he would leap to take it even though he knew that a certain hailstorm of lead would pelt along his trail. And as a consequence the rim of the isle bristled with armed warders, all of them marksmen, who shot at anything that moved, and who had as little compunction in dropping a prisoner as any other sportsman would have in knocking over a partridge.

To add to Captain Kettle's tally of dangers, the phosphorescence that night was peculiarly vivid; the sea glowed where he breasted it; his wake was lit with streams of silver fire; his whole body stood out like a smoulder of flame on a cloth of black velvet. His presence moved upon the face of the waters as an open advertisement. He was an illuminated target for every rifle that chose to sight him, and, far worse, he was a fiery bait bright enough to draw every shark in the Caribbean. And sharks swarmed there. His limbs crept as he swam with them.

To move fast was to increase the phosphorescence; to move slow was to linger in that horrible suspense; and I think it is one of the highest testimonials to Kettle's indomitable courage when I can say that not once during that ghastly voyage did he either hurry, or scurry, or splash. He was a prey to the most abominable dread; he expended an hour and a half over an hour's swim, and it seemed to him a space of years; and when he grounded on the beach of the Isle de Salut he was almost fainting from the strain of his emotions, and for awhile lay on the sand sobbing like a hysterical schoolgirl.

But a sound revived him and sent full energy into his limbs again without a prelude. From the distance there came to him the noise of shod feet crunching with regulation tread along the shingle. He was lying in the track of a sentry's beat.

By instinct his hand dragged the revolver from its beckets on his cap, and then he rose to his feet and darted away like some slim pink ghost across the beach into the shelter of the thickets. He lay there holding his breath, and watched the sentry pace up on his patrol. It was evident that the man had not seen him; the fellow neither glanced towards the cover nor searched the beach for foot-tracks; and yet he carried his rifle in the crook of his arm ready for a snap shot, and flickered his eyes to this side and to that like a man habitually trained to sudden alarms and a quick trigger finger. His every movement was eloquent of the care with which the Isle de Salut was warded.

Kettle waited till the man had gone off into the dark again and the soundless distance, and then stepped out from his ambush, and ran at speed along the dim, starlit beach. The sand-pats sprang backwards from his flying toes, and the birds in the forest rim moved uneasily as he passed. The little man was sea- bred first and last; he had no knowledge of woodcraft; a silent stalk was a flight far beyond him; and he raced along his way, revolver in hand, confident that he could shoot any intruding sentry before a rifle could be brought to bear.

He raced along his way, revolver in hand.

Of course, the discharge of weapons would have waked the isle, and brought the whole wasps' nest about his ears. But this was a state of things he could have faced out brazenly. Throughout all his stormy life he had never yet shirked a mêlée, and perhaps immunity from serious harm had given him an overestimate of the percentage of bullets which go astray. At any rate, the thrill of brisk fighting was a pleasure he well knew, and he never went far out of his way to avoid it.

But, as it was, he sped along his path unnoticed. The blunders of chance threaded him through the shadows and the chain of sentries so that no living soul picked up the alarm, till at last he pulled up panting at the edge of the open space which edged in the grim convict barrack itself.

And now began a hateful tedium of waiting. The day he had fixed with Clare was the right one; the hour of the rendezvous was vague. He had said "as near midnight as maybe" in his message; but he was only able to guess at the time himself, and he expected that Clare was in a similar plight. Anyway, the man was not there, and Kettle gnawed his fingers with impatience as he awaited him.

The night under the winking stars was full of noise. In the forest trees the jar-flies and the tree-crickets and the katydids kept up their maddening chorus. The drumming mosquitoes scented the naked man from afar, and put every inch of his body to the torment. The moist, damp heat of the place made him pant to get his breath. The prison itself was full of the uneasy rustling of men sleeping in discomfort, and at regular intervals some crazy wretch within the walls cried out, "Dieu, Dieu, Dieu!" as though he were a human cuckoo clock condemned to chime after stated lapses of minutes.

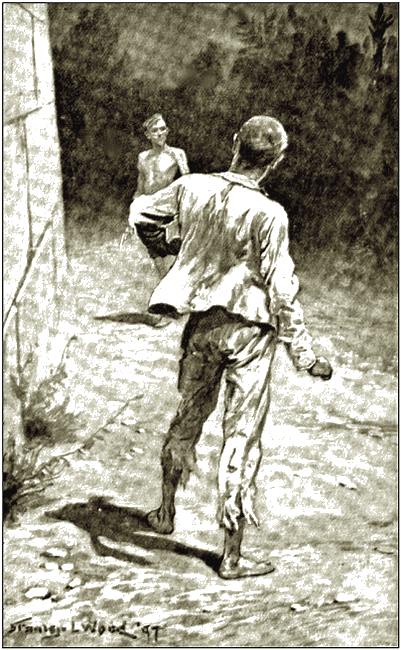

An hour passed, and still the uneasy night dozed on without notice that a prisoner was trying to escape. Another hour went by, and Captain Kettle began to contemplate the possibilities of attacking the grim building with his own itching fingers, and dragging Clare forth in the teeth of whatever opposition might befall. "Dieu, Dieu, Dieu!" rang out the tormented man within the walls, and then from round the further angle of the place a figure came running, who stared wildly about him as though in search of some one.

Kettle stepped out from his nook of concealment, a clear, pale mark in the starlight. The runner swerved, stopped, and hesitated. Kettle beckoned him, and the man threw away his doubt and raced up. The little sailor stretched out a moist hand. "You'll be Mr. Clare, sir, I presume?"

The runner swerved, stopped, and hesitated.

"Yes."

"I am very pleased to have the honour of meeting you. I'm Captain Kettle, that was asked as a favour by Miss Carnegie—"

"Let us get away quick. They will be after me directly, and if they catch me I shall be shot. Mr. Kettle, quick, where is your boat?"

But the little naked man did not budge. "I am accustomed, sir," he said stiffly, "to having my title."

"I don't understand. Oh, afterwards; but let us get away now at once."

"Captain Kettle, sir."

"Captain Kettle, certainly. But this waiting may cost us our lives."

"I am not anxious to take root here, sir, but as for the boat, you've a good swim ahead of you before we reach that." And he told of the way he had come. "There was no other plan for it, Mr. Clare. It would have been sheer foolishness to have brought my boat to this island with all these busy people with guns prowling about. I had just got to leave her at my head-quarters, and you must make up your mind to swim and risk the sharks if you wish to join her."

"I am open to risking anything," said Clare. "It's neck or nothing with me after what I did five minutes back in that hell over yonder. One of the warders—" He broke off and dragged a hand across his eyes. "Look here, Captain, we are bound to be seen if we go round by the beach. Come with me and I'll show you a track through the woods."

He started off into the cover without waiting for a reply, and Kettle with a frown turned and followed at his heels. Captain Kettle preferred to do the ordering himself, and this young man seemed apt to assert command. However, the moment was one for hurry. The night was beginning to thin. So he got up speed again, and the trees and the undergrowth closed behind him.

"Dieu, Dieu, Dieu!" cried out the tormented prisoner within the walls as a parting benediction.

Some men, like the historical Dr. Fell, have the knack, unknown to themselves, of inspiring dislike in others, and Clare had this effect on Captain Owen Kettle. The little sailor's dislike was born at the first moment of their meeting. It grew as he ran through the forest of the Isle de Salut; and even when Clare fell upon a sentry and beat the sense out of him as neatly as he could have done it himself, Kettle failed to admire or sympathise with him.

On the return swim to the turtle-backed island he came very near to wishing that a shark would get the man, although such a calamity would have meant his own almost certain destruction; and when they lay together, packed like a pair of sardines in the shelter pit, under the intolerable sunshine of the succeeding day, it was with difficulty he could keep his hands off this fellow whom he had gone through so much to help.

Clare put in what talking was done; the sailor preserved a sour, glum silence. He felt that if he gave his vinegary tongue the freedom it wished for, nothing could prevent a collision.

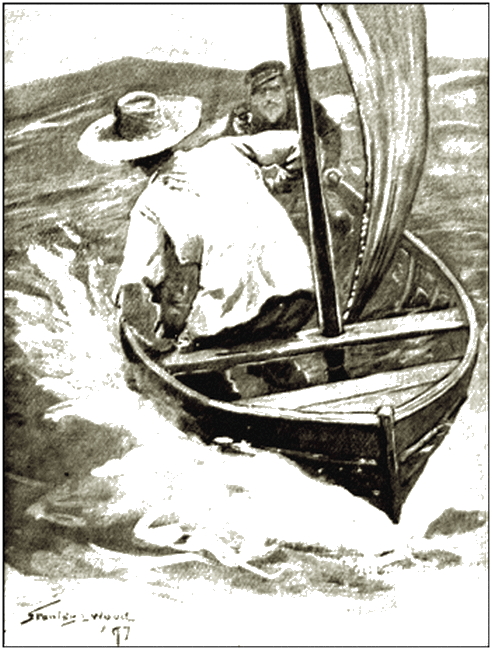

He argued out with himself the cause for this dislike during the succeeding night. They had got the boat in the water, had mastheaded the lug, and were running north-west before a snoring breeze towards the British West Indian Islands. He himself, with mainsheet in one hand, and tiller in the other, was in solitary command. Clare was occupied in baling back the seas to their appointed place.

For a long time the utmost he could discover against the man was that on occasions he "was too bossy," and with bitter satire he ridiculed himself for a childish weakness. But then another thought drifted into his mind, and he picked it up, and weighed it, and balanced it, and valued it, till under the fostering care it grew, and the little sailor felt with a growl and a tightening of the lips that he had now indeed a legitimate cause for hate.

What mention had this fellow Clare made of Miss Carnegie? Practically none. He, Kettle, had stated by whom he was sent to the rescue, and Clare had received the news with a casual "Oh!" and a yawn. He had offered further information (when the first scurry of the escape was over, and they were cached in the sandpit) upon Miss Carnegie's movements, and her condition as last viewed in Newcastle, and Clare had pleaded tiredness and suggested another hour for the recital. Was this the proper attitude for a lover? It was not. Was this meet behaviour for the future husband of such a woman as Miss Carnegie, who was not only herself, but who also wrote poetry for the magazines? Ten thousand times over, it was not.

He sheeted home the lug a couple of inches in response to a shift of the breeze, and opened his lips in speech.

"Miss Carnegie, sir," he began, "is a lady I esteem very highly."

"She is a nice girl," assented the man with the baler.

"She is willing to beggar herself to do you service, sir."

"Yes. I know she is very fond of me."

"And I should like to know if you are equally fond of her?"

"Steady, Captain, steady. I don't quite see what you have got to do with it." He paused and looked at the sailor curiously. "Look here, I say, you seem to talk a deuce of a deal about Miss Carnegie. Are you sweet on her yourself?"

Captain Kettle glared, and it is probable that, if such an action would not have swamped the boat, he would have dropped the tiller and left the marks of his displeasure upon Clare's person without further barter of words. But, as it was, he deigned to speak.

"You dog!" he said, "if you make a suggestion like that again, I'll kill you. You've no right to say such a thing. I just honour Miss Carnegie as though she were the Queen, or even more, because she writes verse for the magazines, and the Queen only writes diaries. And besides, there could be nothing more between us: I'm a married man, sir, with a family. But about this other matter. It seems to me I'm the party that kind of holds your fate just at present, young man. If I shove this tiller across, the boat'll broach to and swamp, and, whatever happens to me—and I don't vastly care—it's a sure thing you will go to the place where there's weeping and gnashing of teeth. How'd you like that?"

"Not a bit. I want to live. I've gone through the worst time a human being can endure on that ghastly island astern there, and I'm due for a great lot of the sweets of life to make up for it. And if it interests you to know it, Captain—I do owe you something personally, I suppose, and you have some right to be in my confidence—if it interests you to hear such a thing, I may tell you I shall probably marry Miss Carnegie as soon as I get back to her."

"Then you do love her?"

"I don't quite know what love is. But I like her well enough, if that will do for you. Hadn't we better take down a reef in the lug? I can hardly keep the water under."

"By James! you leave me to sail this boat," said Kettle, "and attend to your blessed baling, or I'll knock you out of her."

The conversation languished for some hours after this, and Kettle, with every nerve on the strain, humoured the boat as she raced before the heavy following seas, whilst the ex-convict scooped back the water which eternally slopped in green streams over her gunwale. It was Clare who set up the talk again.

"Did she know anything about those plans of the French fortresses?"

"Miss Carnegie had the most definite ideas on the subject."

"I suppose she'd found out by that time that I really did get hold of them out of the office myself, and sell them to the Germans?"

For one of the few times in his life Captain Kettle lied. "She knew the old yarn from start to finish."

"Well, I was a fool to muddle it. With any decent luck I ought to have brought off the coup without anybody being the wiser. I could have lain quiet a year or two till the fuss blew over, and then had a tidy fortune to go upon, and been able to marry whom I pleased, or not marry at all. Eh—well, skipper, that bubble's cracked, and I suppose the best thing I can do now is to marry old Carnegie's girl after all."

"Then you've quite made up your mind to marry this lady?"

"Quite."

"That's what you say," retorted Kettle. "Now you hear me. Miss Carnegie thinks you are in love with her, and you are not that by many a long fathom; so there goes item the first. In the second place, she thought you were sent to Cayenne unjustly, whereas, by your own showing, you're a dirty thief, and deserved all you got. And, thirdly, I don't approve of squeezing fathers-in-law as an industry for young men newly out of gaol."

"You truculent little ruffian, do you dare to threaten me?"

"I'd threaten the Emperor of Germany if I was close to him and didn't like what he was doing. Here you! Don't you lift that baler at me, or I'll slip some lead through your mangy hide before you can wink. Now you'll just understand; for the rest of this cruise, till we make our port, you stay forrard, and I'm on the quarter deck. If you move aft I'll shoot you dead, and thank you for giving me the chance. But if you get ashore all in one piece, I'll spike your guns in another way."

"How?" asked the man sullenly.

"You'll find out when you get there," said Kettle grimly. "And now don't you speak to me again. You aren't wholesome. Get on with your baling. D'you hear me, there? Get on with that baling: I don't want my boat to be swamped through your cursed laziness."

"D'you hear me, there? Get on with that baling."

NOW, to which port it was of the British West India Islands

that the lugsail boat and its occupants arrived I never quite

made out, and indeed the method in which Captain Kettle "spiked"

Mr. Clare's "guns" was hidden from me till quite recently. A week

ago, however, a letter of his drifted into my hands, and, as it

seems to explain all that is necessary, I give it here exactly as

it left his pen.

West India Islands.

To Miss Carnegie.

Jesmond Street.

Newcastle, England.

Honoured Madam,

Am pleased to report have carried out part of yr esteemed commands. Went to Cayenne, as per instructions, and took Mr. Clare away from French Government, they not consenting. Landed him in good condition at this place. Having learnt that he did steal those plans, and, moreover, he saying he did not care for you the way he ought, have taken the liberty to guard lest he should trouble you in future. To do this, found old coloured washer-woman here (widow) who was proud to have white husband. Him objecting, I swore to tell French Consul if he did not marry, and get him sent back to Cayenne. So he married. She weighs 250 lbs. I enclose copy of their marriage lines, so you can see all is correct.

Trust you will excuse liberty. He has made one escape; you have made another.

The weather is very sultry here, but they say there is fine scenery up-country.

Shall get English magazines some day, when things blow over a bit, and I can come that way again, to look for your poetry.

Hoping this finds you in good health as it leaves me at present.

Yrs obedient.

O. Kettle,

(Master).

1 Inclosure.