RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

MR. S.J. LIVINGSTON was not a poor man, but I think he may be described broadly as an ambitious man. He had an air that some people (other than customers) found arrogant.

Soon after the War began he tried to hold up the British Admiralty for a million sterling, free of tax, and an earldom; and when this did not come off he crossed Whitehall and tried the same game on the War Office. He got hold of some bland ass there who irritated him into saying more than was judicious, and left the building under arrest. The magistrate before whom he was hauled called in doctors to enquire into his mental state, and was with difficulty persuaded to dismiss him with a caution.

He had not gone to either of these seats of military learning on the strength of his appearance alone. He was a business man, and had no mind to be fubbed off with underlings. He knew it would require one of the Heads to be man enough to give him what he asked for, and he saw to it that weighty introductions carried him direct to a Head—both at the Admiralty and the War Office. The only trouble was, neither Head that he saw was big enough for his job, or S.J. Livingstone would have got what he asked for—or been taken out into the yard and shot before he could talk. For myself, I think I should have shot him. as being on the whole the safer, and certainly the cleaner course. However, perhaps that is a matter of taste. You shall judge for yourself.

But read next a word or two about the man himself. Livingstone, he called himself, and by reason of a birth in Paisley, affected a Glasgow accent, rather of the Pollockshields variety. (This is a cross between cleft palate and German). His father had been Solomon Levenstein, who had exchanged brutal ill-treatment in the Frankfort Ghetto for the doubtful delights of being a rabbi in Scotland. (Conceive a Jewish priest in an atmosphere of Wee Frees, U.P.'s and Episcopalians!). S.J. Livingstone, son of Solomon Levenstein, had never visited Germany, but loathed it and all its contents from the bitter tales of Ghetto persecution dinned into him during his upbringing.

Old Solomon, in his way, was a well-read man; S.J. was a better—mainly in the direction of natural science. I think if somebody had subsidised S.J. and he had specialised in one or two branches of chemistry or chemical physics he might have been something big, though again this is open to question. It is on the cards that when he discovered something good—Meltite, for instance—he would have dropped pure research like a hot brick and struck out boldly for commercial affluence. He was a good deal of a mixture—which is perhaps the same thing as saying he was altogether a Jew. For instance, no outsider would have suspected him of collecting enamels; but he did, lavishly and worshipfully; and told no one, so that prices should not be raised against him.

In commercial life, S.J. Livingstone was a seller of dyewares in Bradford (Livingstone & Co., 29, Chapel Row. Agents for Dresdner Alizerin-Gesellschaft. Telegrams:—"Explorer," Bradford). Up to the beginning of the War, he did pretty well, sold a decent weight of goods in his office, and more, after the manner of his kind, at the political club where he lunched, and at the golf club where he kept his liver down to gauge on Saturdays. On Sundays he was invisible. He spent half that day in chemical research—he was chasing a cheaper synthetic indigo—and the other half in gloating over his enamels. No living soul ever caught him at either. Between whiles his housekeeper fed him sumptuously, although he bullied her.

After war began he made money hand over fist. How he ran German dyewares into England without getting dropped on I know, but shall not tell. Probably the Government know, too. The British Government makes a specialty of doing silly things, we all admit, but it is not what the Oriental calls an All-the-time Fool. We all knew the Government wanted dyewares to get into the country for khaki and other things, and presumably the Government knew when to wink. Anyway, Livingstone & Co. were the firm with the goods, which they bought for shillings a pound, and sold for pounds a pound, to S.J.'s delight, and to the noted increase amongst his enamels. It was just after the December balance-sheet he cut out the big Yankee collectors over that bit of old Limoges that Christie's called the Scarlet Madonna. Also he bought twenty dozen Pommery '06.

Then one Sunday morning he blundered upon Meltite by an absolute fluke.

It was untamed enough when he first mixed it, and I gather that he narrowly escaped with life. As it was, he was badly burned, his laboratory in the cellar was wrecked, and the City Fire Brigade had an interesting time salving the balance of the house.

Hut he was skilled enough at his job, and once he knew the nature of the mixture he had stumbled upon, it was easy to arrange its proportions so that it could be handled in comparative safety. Incidentally the City Corporation helped him. They were using a mechanical mixture of an iron salt and powdered aluminium for welding together the ends of tram-rails, and he studied their methods. The Corporation called their stuff Thermit. There is no secret about it. Thermit is used for a score of purposes, and latterly the ingenious German loads it into his Zeppelin bombs. S.J. Livingstone's mixture was like Thermit, only more so. He added to his powdered aluminium a substance that gave up its oxygen with more astonishing quickness, with the result of producing even more amazing heat than burning Thermit gave out.

After inspecting the fused remains of his cellar, the inventor hit upon "Meltite" as a name for his discovery, and then spent a rapturous afternoon gloating over his enamels, and thanking Allah that he kept them in a fireproof safe. He went to the Seascale links for a couple of days then, and because he was thinking of something else the whole time, played golf extremely badly. But exercise and sea air crisped his brain, and lifted his outlook from the retail view.

Half the world was at war. This was no time for a new Limited Company, and anyway that infernal Treasury would probably stop a capital issue. Besides, if he took out a patent, and published a specification, Germany would jump his claim as surely as mails ran to Rotterdam.

"No," he declared—and smashed a new driver into the turf and sent the head flying. "No, a Government is my mark, and the British is the nearest. The German, of course, would be the easier to handle, but strafe Germany, anyway. The British Government—and keep the mixture a secret till they pay:—and then let them work it. Caddy, give me a club that won't break. I think I'll make an iron shot of this now."

Thereafter he sold the business of S.J. Livingstone & Co., 29, Chapel Row, Bradford, to an unintelligent Christian (being very shrewdly of opinion that no more German dyewares would slip through before the end of the war), and settled down to draw out a prospectus for Meltite that would convince even a high Government official.

Shells for naval and military cannon, loaded with Meltite, were the basis of his first idea. On leaving the gun they would be fired by means of an ordinary time fuse, and could (1) arrive as a mass of molten steel—highly recommended for annoyance to trenches; or (2) could warm up after penetrating armour—a special line this setting fire to refractory warships.

S.J. Livingstone was not a literary genius, but be was a salesman, and a man that can unload dyewares in Bradford and Manchester can sell anything. His prospectus of Meltite was a gem in its way, and be was justly proud of it. But he did not send it through the post. He got the best introductions possible to the biggest man available at the Admiralty, and took the prospectus in his hand to back up his voluble tongue.

He failed at the Admiralty to make a sale, as has just been recorded, but I know no details. All I could get out of him was that the officials at that office were "a pretty tough lot, but, according to their limited lights, sound." S.J. did not get his knife into the Admiralty as be did into the War Office, and I think it was more the particular "bland ass" (his term) who received him there than the failure to affect a bargain that got on his nerves. He was always rather an arrogant man with those he considered weaker than himself.

For a moment, after that second rejection with its police-court sequel, be was minded to seek the sure market of Germany. They, at any rate, had no qualms about the methods by which they killed an enemy, so long as they killed him efficiently, and anyway Germans knew enough about elementary science to understand a first-class invention when they saw one. He dined on this, in style, and at the Café Royal, and came out, and shook a fist at darkened London.

"Curse you!" he said to Great Britain. "I don't care a row of beans about you, but I'm not going to help the blighters who tormented Solomon Levenstein in Frankfort. And I am going to make Creation hear all about Meltite, even if I don't get paid C.O.D. Afterwards, when you fools here do get wise to what you've been offered, the price will be two millions instead of one, with the earldom thrown in as per before. Dirt cheap, too! Only twelve hours' cost of your blessed war. Then I'll settle down and marry—yes, marry some real nice girl with a lump of money—and have a family, and try to feel a real Englishman. And I'll have the best collection of enamels on earth—not on view to the public, or they'd be raising my income-tax. 'The Earl and Countess of Livingstone invite you to Livingstone Castle to meat tea, and afterwards to view their celebrated enamels.' And perhaps we won't do it in style—I beg your pardon."

"Not't all," said the man whose hat he had bashed in. "Just rehearsin' your speech, I suppose? Or have you been dinin'—like myself? What do you say to joining me in a small glass of particular old fine champagne brandy to keep it all quiet? You'll have to pay for yourself because of non-treating order, but I'll pay for myself next round, so that'll be all right."

Now S.J. was not in the mood to come down from the clouds and drink brandy with a stranger who had obviously "dined" already, and the stranger was sharp enough to notice this. Said he:

"Don't strain yourself to come in here if you're due at the club. But I'm bound to talk to somebody about my yacht, or else I'll burst, and I thought you'd do."

Thoughts snapped and sizzled in S.J.'s brain.

"A yacht, have you?"

"Well, I call her that when I want to put on edge. Admirin' friends describe her as a coffin with the motor too far aft."

"Thank you," said S.J. Livingstone. "I'll come in with you and have that cognac."

"Come along in then, or some sweet young thing will trip along and ask why I'm not soldierin', and I shall bring the blush to her damask cheek by explaining how few of my legal set of insides I've got left on the premises. You unsound, too?"

"Too old," said S.J., who was thirty-five. "Turned forty-six, I'm sorry to say, though perhaps I don't look it. How big's this yacht of yours?"

"That depends whether you view her with the mellow eye of evening, or run her over with a cold two-foot rule. Just now I could take her round the world with a crew of one, and if there was a German to kill at the far end, I'd take her round twice Gad, man, I'd give something to be sound! But it's no use lying to those infernal Army vets. I know, I've tried."

"It must be beastly. Then she's an ocean-going yacht?"

"Good Heavens, yes, man; though, frankly, she's a bit damp if there's much sea runnin'! But in anything like smooth water, if her sparking plugs are clean, and she's pleased with her mixture, she can kick out eleven—yes, and up to eleven-point eight sometimes, as easy as look at you. And I've just shipped a patent washstand that'll beat the band. Can't leak inboard however rocky the valves get."

"Why haven't you hired her to Government?

"Because the beasts don't know a soft thing when they see one. She fouled two of their blessed conditions out of eight hundred and forty-three. It was my own patent balance-rudder that floored her finally. They said she'd turn turtle if I gave her a hard-over helm at top speed. Well, so would a loco go smash if you ran it full pelt into the buffers. It's a thing a man doesn't do, that's all. But let's clear out of here! That pretty girl with the gold hat there by the pillar is going to shove a white feather on me. I know it by her thoughtful eye. And I shall be saying something I shall regret to-morrow morning if she does. Have you a club anywhere handy?"

"I haven't a London club."

"Well, I've a pot-house of sorts in St. James's Street. We'll go there. Drat that girl!"

IT was a queer and one-sided partnership that was fixed up between Jew and Gentile that night. The Gentile, who was Sir Thomas Hillcote (seventh baronet), hankered after nothing except "a bit of sport with the Germans." The Jew's single idea was to advertise Meltite so noisily that even the British Government must see the need to buy it up at maker's terms.

"Hallo, Tommy!" said a man coming into the club smoke-room, "How's Drowning Made Easy? Still afloat?"

"No, I've put her on wheels and made her into an armoured car," said the owner genially.

"Well, call on me when you want a spare shuvver. My neck's my own at present. Nobody seems to want it."

"That's Bell," said Hillcote, as the man carefully picked his way to a chair at the other side of the room. "He's got locomotor ataxy. He and I both crocked in the Navy the same week, and got fired out by a Medical Board on the same day. Rum, isn't it?"

"Oh, you're a naval gentleman, are you?" said S.J.

"There's another blow. I've got even Navy rubbed off me now, have I? As a matter of interest, was it one of our genial archbishops you took me for? Alack, my fatal gravity of manner."

"Then you can navigate, and all that?"

"I was a most promising officer. Everyone said it of me It was a thing I couldn't avoid. The First Lord sobbed out that now, indeed, the country would go to the dogs when they lost me. I say, Mr. Isaacs, I mayn't stand you a drink because of the brutal Laws of the Land—Section: Treating—But you may absorb mine when I'm not looking. I've about got my load. My crumbs, but wasn't that a pretty girl with the gold hat?"

"If you carry out my scheme, you could marry ten girls with gold hats."

"Not't all, my good chap. I'm not a Turk. But, by Jove, I'll tell you what! If you'll let old Tinkle Bell chip in, we'll call it a deal. He's having a filthy time, poor dear, just now, what with pain, and being flinty, and all that, and if be saw a decent chance of being hung as a pirate, or anything in that line (which is what your scheme seems to amount to)—excuse me, Mr. Benjamin, if I'm a bit fuzzy about it—he'd freeze on to it with both claws. By the way, I suppose you are an Englishman?"

"Rather! Sorry if you thought I was anything else."

"Not't all. But you will waggle your hands in moments of excitement. Pedigree started in Asia, I suppose. I shall want a bit of proof that you can deliver the goods in the dynamite line you've been speaking about."

"Meltite."

"Very likely. Never heard of it. I wasn't one of the scientific johnnies. I was merely a salt-horse lootenant. Well, prove to me and old Tinkle that this blowy-up stuff will eat holes in a ship's plating, as you say, and we'll motor you off to any old point in the North Sea you care to name till we've sunk all the shipping afloat, or run out of bombs, or been strafed ourselves, whichever comes first. Is it a bet?"

"You're just the gentleman I want. Look here; read that! There's a full specification of Meltite."

"Nothing doing, most noble Abraham. I don't care a row of pins for typewritten matter. The letters jump about so. Nothing but the genuine article at work will convince us. Let Tinkle and me see that with a sober morning eye, and we'll get busy with a speed that will surprise you."

Sir Thomas Hillcote's motor-boat does not appear in either Lloyd's or the Yachting Register as Drowning Made Easy, but as her real name brings up other memories, it may here be suppressed. Anyway, amongst her intimates and acquaintances she is sufficiently well known by her nickname.

She was the darling of her owner's heart, and largely the product of his lamentable inventive faculties. From her misplaced engines to her ridiculous bow, from her capstan (whose barrel would not bite) to an enormous balance rudder that would have capsized a battleship, she was a museum of enthusiastic ideas gone wrong. Ex-Lieutenant Thomas Hillcote swelled with pride every time she tried to shake him overboard. Ex-Lieutenant Bell was glad to be at sea once again in anything that would float. He had been desperately afraid of dying in his bed these last few weeks, and now, with the low land of the Thames Estuary dropping into the grey seas astern, the fear was easing. There was war and work away through the North Sea mists ahead, and perhaps luck.

"Can you cook?" S.J. Livingstone was asked.

"I never tried. I've always been above that sort of thing."

"Then you've got to learn. You aren't a watch-keeper, and seeing as how we don't carry a crew this trip, you'll have to cook—and cook well, or you'll get the foul aide of Tinkle's tongue. When we bring up alongside the enemy you'll be gunnery lootenant, and you take charge, and we two do as we're told. But till then you're cook, Father Isaac; and as we're bare Navy in the way of drink, and there's no whisky on board, you're to stand-by with hot cocoa whenever it's wanted. Got that? We'll worry along on cold tin and biscuit for the rest. But we're not going to be done out of our lawful cocoa, and don't you forget it. You may be sick between-whiles, though what in thunder you're being sick for in smooth water like this beats me! Good Heavens! there's a busy devil of a destroyer buzzing up at about fifty knots, and wasting my country's fuel-oil most scandalously, just to interfere. Here. Tinkle, you talk to her, and tell her we're out after mackerel. Say I'm below, writing to a lady friend who wears a gold hat."

Ex-Lieutenant Bell tried to be formal, but was recognised.

"Haw, haw! You and your mackerel! Glad to see you looking so fit, Tinkle. You'll be back as a giddy brass-edged commander before the week's out. Go easy with that wheel, or you'll twist off Tommy's patent rudder. If you stick to your present course you'll land on to the feather edge of my fancy new minefield. You might call me up if they don't go off, and I'll come and set 'em better. You gay kipper, why doesn't Drowning carry a pilot? But I suppose that's Tommy. Trust Tommy for running on a graveyard if there's one handy. You bear away four points starboard, Tinkle, and you'll live a lot longer. Keep good."

The destroyer grunted and bucked, and ran away over the edge of the horizon at the speed of a railway train. She spread the news amongst the British sea police patrolling the North Sea, and they in their turn jeered at the motor-boat, and let her through. An important small cruiser wigwagged "Captain's compliments to Sir T. Hillcote, and he didn't care for mackerel, but would like brace of grouse." An ugly tug, with a three-inch gun stuck through her towing-bridge, hailed through a megaphone that she could supply a stale tinned tongue for bait if fish were not biting freely. A draggle-tailed motor patrol-boat, whose crew all wore forked beards in polite imitation of Admiral Tirpitz, offered to bet Drowning Made Easy three gallons of petrol to a pint of lubricating oil she hadn't got more than three cylinders firing at that precise moment—and the bet, for painful reasons, could not be taken

"We're making a dreadful stir," said S.J. Livingstone once, between spasms. "I'd no idea there were so many British ships about."

"Who did you think ran the North Sea?" Bell asked. "The Germans? You've been reading the papers, Uncle Reuben. You're entirely wrong. It's ceased to be the German Ocean quite a lot of months now, and we've taken possession of it ourselves for keeps. Bring me a bowl of cocoa, Reuben, hot and gummy, and mind you don't slop it about on the oilcloth like you did last time. Also bring me of the sandwiches, cold-dog variety, one; class, non-bendablc, I have a twist on me, Reuben, for the first time for three months. After you have completed your important duties as steward, you can stand-by, and get a couple of your torpedoes, or whatever you call 'em, ranged ready for action. We are not exactly on our cruising ground yet, but there's a good thick North Sea fog coming down, and you meet all sorts of funny things in fogs."

"I don't think I can do it," said S.J. faintly. "This beastly little boat lurches so, and I've been so sick, I've no strength left."

The man with locomotor ataxy dropped his drawl, and yapped in the old style of the quarter-deck.

"Carry out your orders! This is wartime! If you don't do as you are told, I will fling you overboard. We've no use here for extra ballast. If you can't do it yourself, I'll take charge of your Meltite, or whatever you call it, and make what I can of it myself."

"You coolly say you'll rob me?"

"Like a bird. Carry on, now!"

S.J. Livingstone found himself doing as he was told. These ex-naval lieutenants at sea were very different people from the thirsty souls he had talked with in a St. James's Street club, and he suddenly found himself scared. The attitude of Sir Thomas Hillcote on the matter clinched things.

"I resent Mr. Bell's treatment," said S.J. as he was bringing aft the ordered cocoa.

"You can resent till you're black in the face," the baronet informed him cheerfully.

"And I shall square up for it when I get home."

"Home! Who's thinking of getting home? We're out here to play games with Germany, with half the British Fleet standing by ready to interfere. You haven't a cat-in-hell chance of seeing your happy home again, Moses, my dear. You carry on and don't worry about the future, or you'll meet with present trouble that'll cause you pain. That's a sound tip. Old Tinkle's got the devil of a temper now he's seedy, and he'll break your arm or crack your jaw as soon as look at you if you don't carry out orders smartly. I'll help him if necessary."

Now I don't think S.J. was a coward, but he was first and foremost a business man, and he was beginning to regret very much that he had launched Meltite with these strange associates. His idea, of course, was (with their help) to advertise the stuff and sell it. Theirs was an entirely different proposition. They looked forward to doing the maximum of damage with it—and there their programme ended. They did not anticipate getting back to England. They had no care whatever for the future of Meltite or its inventor. The disgusting part of it was there was no wriggling out of the deal. His earldom, his two millions, his beautiful enamels—

"Below there. Stand-by with those torpedo things. Tommy, bear a hand to do as Reuben tells you. Neither of you is to use a word of English. Hear that, Reuben? If you let out a word of English I'll shoot you like a rat. I'll do all the patter. Understand? And, Tommy, fish out those German uniform caps for the pair of you. I've got mine bent."

S.J. Livingstone went out presently into the cold, foggy air on deck with heavy burdens, and to his amazement saw a German naval ensign whipping and snapping from the motor-boat's jackstaff, and her wheel held by a starched and arrogant German officer in whom he could hardly recognise the late Mr. Bell, of St. James's Street. A steamer of 3,000-tons loomed through the fog, and the motor-boat was edging down on to her on a parallel course.

"What steamboat's that?" The hail went in harsh German.

"Steamship Rhein, Rotterdam-Amerika Line, Vanrennan Master, from Galveston for Rotterdam. Cotton loaded."

"Heave-to, and I will see if I must sink you."

"But, thousand devils, captain, I'm carrying cotton I tell you, and it's for Germany."

"That's what I wanted to know. Get out your port boats, and row clear as soon as you like. I'm coming up to starboard."

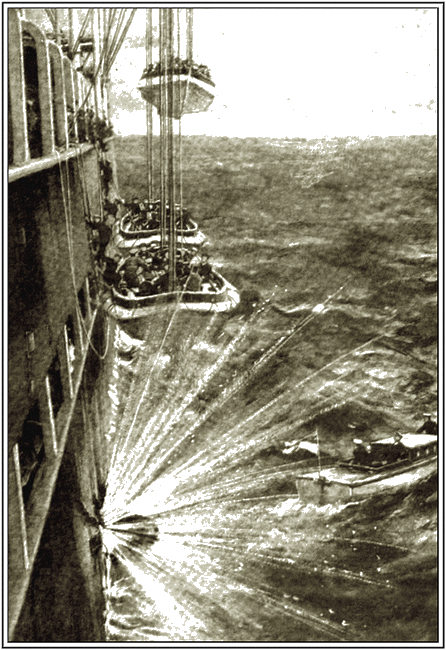

The Dutch skipper danced on his bridge, but his crew carried out the orders without waiting for him to repeat them. Then Bell put the motor-boat alongside, and S.J. did the rest with the efficient help of Sir Thomas Hillcote.

The charge of Meltite was made fast to an electro-magnet, which was fed by an accumulator of S.J.'s own design. This was not active till it was clapped against a ships plating, but once there, a switch was automatically thrown in, and the whole affair clung in place like a limpet. Simultaneously a small detonator fired the Meltite.

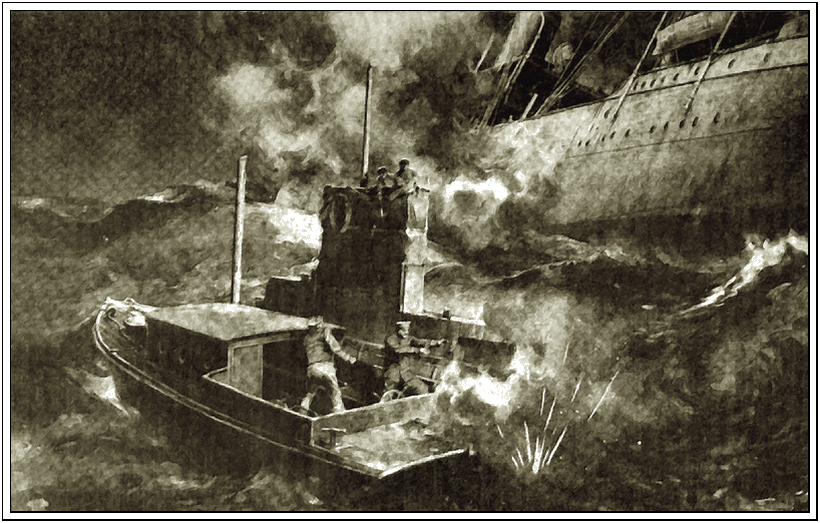

Drowning Made Easy slid away with a spurting, sputtering spray of molten iron pursuing her, and a fine firework effect taking place over her counter.

The motor-boat slid away with a spurting,

sputtering spray of molten iron pursuing her.

"My God!" said Hillcote. "That fiery stuff is eating the plating away as if it was so much tissue paper, and inside the hole things look like a blast-furnace. That's the cotton, I suppose. Aren't those ducks getting out their boats in a number-one hurry? There goes the owner down off the bridge to get the ship's papers before he leaves for home. By gad, Look! The deck's catching now. Aaron, my lad, your stuff's big medicine, but it advertises itself a bit too much for my taste. We shall have the British Navy round here with fire engines and first-aid kit in two jiffs, and we don't want to meet them. No, not any. Tinkle, my humble friend, bear away to the cold North for half an hour, and I'll bop below and whoop up the coffee-mill another knot or so."

"You might strike that infernal flag before you go; and, here, take my fancy hat with you."

They fired a second ship that night, copper-laden, and were fired at by a third. The third ship carried a profane Yankee officer on her bridge who had apparently been ruffled by the British Navy in the immediate past, and said he would see all Germans in hell before he answered their questions. He backed up his remarks with a .380 automatic Colt, with which be made remarkably close shooting.

Next day Sir Thomas Hillcote broke down and was put in his bunk.

"I told you my insides were unreliable," he gasped at them between spasms. "Leave me the morphia, and I shall be quite, merry and bright. Don't you worry about me, Tinkle. I'll dream about that girl with the gold hat. You carry on, and Jonadab will help you, Jon's getting quite a second Nelson with all his experience. Oh, corkscrews! that was a twinge. I'd take a cast closer in to Rotterdam if I were you."

"We've only just about enough petrol to get home on," said S.J.

"Who wants to get home, my good Jeremiah? There's lots more mischief to be done out here if all goes well and the British Navy doesn't butt in. Just think: all this stuff into or out of Rotterdam is for or from Germany, and because Germany's got a pull in London, the British Government doesn't interfere."

"That's true enough," said the man who had run dyewares.

"Well we, not being politicians, and knowing what's good for the country, do interfere. That's all. I suppose a lot of pious people will want to hang us for our pains, but till we are hung we'll go on with the missionary effort. Tinkle, get busy. There's a steamer coming. I can feel the vibration of her propeller on my sore liver. No, propellers; she's twin screw. Hop, you lazy scoundrel, or she'll be past us."

"Sir Thomas is bad," said S.J., when they got back on deck.

"Have you only just found that out? That new fellow's coming towards us. I'm going to turn round. Mind you don't get shot overboard when I give her the helm! Here! Stay on deck there, you Reuben, You needn't worry about Tommy shooting out of his berth. I'll keep him on the lee side."

Once more ex-lieutenant Bell appeared as the complete German naval officer, and barked his remarks in a foreign tongue. The new ship was a Swede, out of Rotterdam for New York, full to the hatches with German leather goods, dyewares, and chemicals. "Those beasts of English," announced her captain, "are respecting the rights of neutrals this week, whatever they may do next."

"Got good freights?"

The Swede shrugged apologetically. "Well, in war time, illustrious Herr, we neutrals all look to make a little extra bit. Be careful—Himmel! be careful; you will run me down."

"Not a bit of it. I'm not going to ram. It's only a sort of game like 'tag' we're playing. Now then Rube. On the port quarter. Clap on your poultice when I swing her in, and don't get flung overboard if you can help it. Poor old Tommy's patent rudder's a bit fierce. Great Scott, man, but you set that fuse mighty short! You'd better put some oil on those burnt hands before the air gets to them."

"You German beasts," the Swede stormed, "you have set my ship on fire."

"I hope so, Mr. Neutral. Rather pretty effect I call it. To see a big chunk of plating dissolve out into mere sparks and roman candles is astonishingly pretty to the simple sailorman. I should call away your boats if I were you, or you'll get wet feet. Excuse my butting in with advice, but you seem rather to have lost your head, and by the smell, those leather goods you were bucking about are beginning to singe."

Now the night was dark and the night was clear, and it sang with wind; and the steamboat flamed like a torch; and by the rules of war Drowning Made Easy should have faded from the scene of her exploit with all possible speed. But the Swede bungled his boat-lowering badly, and Bell could not tear himself away. He bawled advice with an acid tongue, and in the event of the advice not being acted upon efficiently, be stood by to save life.

"We shall be seen here," said S.J., frostily.

"Bound to be. Party in the front seats at the firework show always is spotted by the whole audience. But a man couldn't clear out whilst there was a possibility of those fellows frying unless be was a darn German. I'm sure you see that, Rube!"

"Ye—es," said S.J. Livingstone, and stepped down into the after well and sat there. Something inside him bumped with heavy foreboding.

The German submarine must have come up awash, and quietly stalked them by the light of the burning Swede.

The German submarine quietly stalked them by the light of the burning Swede.

Bell did not see her till she was close alongside. They called on him to surrender. He very naturally turned on his power, and tried to bolt. At the same time he threw into the grey North Sea the last remaining Meltite fire-maker, where it burst into torrid flame, and exploded in a volcano of fire and steam. After a careful inspection—a very careful inspection—the Germans shot Bell in six places.

Then they bore down alongside, and made fast.

The boarding party found Sir Thomas Hillcote dead in a bunk below. He had bitten through his lower lip because he did not wish to call out and disturb his two shipmates on deck who were trying to give a lift to the British Empire. They examined S.J. curiously, enquired his name, and, on hearing it, transshipped him with politeness.

One of the officers leaned over Bell, who was very nearly gone. "Ha, I thought I knew you. We met once at Kiel if you remember, at the regatta, I'm sorry, but it's the fortune of war."

"Don't apologise," gasped the man with locomotor ataxy. "I've got to windward of the Admiralty—this trip, and died in my boots—at sea. At sea! I've—had—luck."

Down below in a clammy cabin of the U-boat S.J. Livingstone found himself treated with a curious courtesy that after a while began to chill. It flashed upon him that cannibals might be similarly courteous to a missionary that they proposed to—well—attend to later. These German officers knew his name, the style of his firm in Bradford, the nature of his proceedings at the British Admiralty, his rejection by the "bland ass" at the War Office. They mentioned that eminent officer's name, and could imitate his manner. They even knew about S.J.'s taste for enamels, and had a catalogue of his more recent purchases. It was all most uncanny. They gave him his favourite Pommery to drink.

They knew all about the powers of Meltite, and recited to him a list of ships destroyed and a description of what they looked like as they burned. It was all very accurate and scientific and unnerving. An outside observer would have noticed one curious change in S.J. He was not the least arrogant now, either in manner or look. I don't say he cringed, but—well, there was a change.

They even, in a wooden way, got on to his pedigree.

"You are not English? No!"

"Certainly I am. My name is Livingstone. Unless you call it Scotch."

"Livingstone? Ah, but before you changed it? What!"

S.J. kept a sullen silence.

"Answer me. Was it not Levenstein?"

"Yes," said S.J., and felt his self-respect oozing from him.

"So! And now you are going to tell me—pleasantly, and without pressure—how Meltite is made?"

"I do not know. I forget."

"So! Then I hope you like chlorine. Because, until you remember, I shall put you in the compartment with our accumulators, which just now are gassing, and there you will perhaps recover your memory before it is too late."

But S.J. Livingstone came of a race that in the past had had teeth pulled rather than draw cheques which they did not consider lawfully due, and he coughed, and spat, and choked, but parted with no formulae. He was pretty far gone when the U-boat ran into her home port, but he showed not the smallest signs of yielding.

The Germans were eminently businesslike. S.J. Levenstein, dead, was no use to them. Alive, he was full of Meltinitic possibilities. So they kept him alive, and alternately treated him well and vilely. He was interviewed by small personages and great, all of them in uniform, some of them polite, most of them overhearing, some of them proffering gifts, many of them offering threats; but to all of them he was unyielding. He might be this Levenstein they were talking about. He might have heard of Meltite. But, anyway, at the moment he had forgotten the composition of Meltite, if, indeed, he had ever heard it. They could not budge him past that, by either kindness or cruelty.

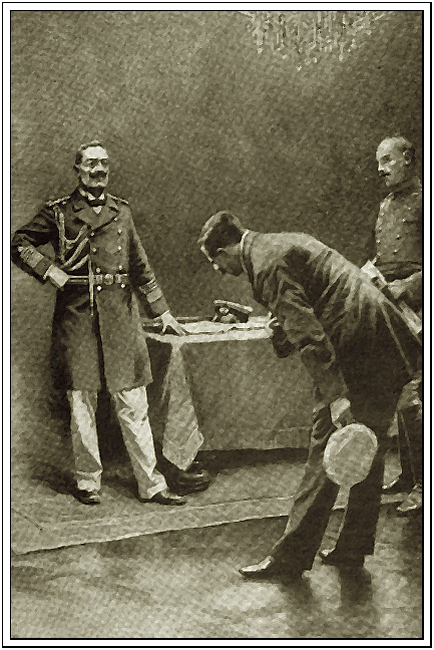

At last he was brought before the Greatest Personage of all, a tragic, twitching cripple, and he set himself out to charm.

At last Livingstone was brought before the Greatest Personage of all.

"I understand, Mr. Livingstone, that you were a Prussian by birth, a British subject by early upbringing, and are a cosmopolitan by taste. Well, it is our loss, because you are a man of ideas. But I am not going to quarrel with your choice. You have made a great invention in Meltite. You see, I am not going to belittle it. And if I say it is great, it is great. You offered it to the London Government. They, being fools, as I have shown many times already, refused it. I believe they did not even refuse it civilly. You have stated your price—a million sterling and a peerage. I will give it you."

"My price is two millions, now that Meltite is proved."

"Two millions be it. I do not quibble over marks about a thing I intend to get."

"There is also the British peerage."

"I can buy that for you, too—as I have bought for money down other British titles for my people when I wanted them."

"Very well, sire," said S.J. Levenstein. "Get me from, the politicians an English earldom, and give me two million British pounds sterling, and I will give you the formula for Meltite."

"That shall be arranged," said the Greatest Personage, and S.J. was taught by his guide how to back out from the Presence.

There the matter rests for the present. S.J. Levenstein (or Livingstone) resides in dignified seclusion and security in a Prussian castle full of enamels, whilst arrangements are being made to pay him his price. They feed him on the richest food he cares to order, and he may bathe in Pommery '06 if he so desires.

But there is one very sound reason why the Germans will not succeed in buying Meltite.—George V., King of England, grants titles: he does not sell them.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.