RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

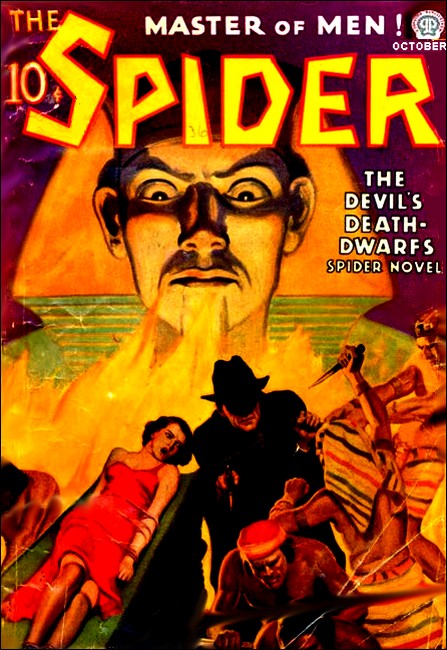

The Spider, October 1936, with "Death at the Matinee"

A torn copy of "Variety" and a little old lady lead Ed Race, ace vaudevillian, along a murderer's twisted back-trail—to a thundering climax of juggled six-guns, with only death as an audience to his off-stage act.

TO Ed Race, the proceedings were eminently disgusting. The big man with the pale-green necktie had no business punching the little man in the face that way; and when he tweaked his nose, it wasn't funny at all.

However, the dozen or so people who sat in the otherwise empty orchestra of the Clyde Theatre were laughing their sides off, so Ed thought that maybe it was his own sense of humor that was going stale. Those dozen men were the typical Broadway about-towners who invariably showed up at Monday morning rehearsals, and they ought to know what was good in vaudeville and what wasn't.

Ed shrugged and slouched glumly in his first-row seat between Leon Partages and Jimmy Oglethorpe. Partages, the owner of the Clyde, Ed's boss, and the boss of the whole countrywide Partages Circuit, seemed to think that it was funny as the dickens for Frankie Brown to be smacking Harry Brown every time Harry made a wisecrack. So did Jimmy Oglethorpe, Ed's young friend from Washington. Jimmy was one of Mr. Hoover's Special Agents. He had just come in to New York on government business, and Ed Race had been showing him around in his spare time.

Ed's gun-juggling and acrobatic act was the headliner at the Clyde, and Ed had just finished rehearsing, so he was now watching the other members.

Harry and Frankie Brown, billed as the Two Brownies, finished their routine with a slam-bang, and bowed themselves off the stage.

Partages was laughing deep in his fat belly, and he turned to Ed, said between gulps of laughter: "What do you think of it, Eddie? Harry was okay as a comic by himself, but taking his brother into the act was a stroke of genius. Now he gets off all his gags with an extra kick."

Ed made a sour face. "Sorry, Mr. Partages, but I can't see the fun of it. Slapstick comedy never appealed to me." He turned to Jimmy Oglethorpe, on his right. "What do you think, Jimmy-the-G-Man? Was that act funny?"

Jimmy Oglethorpe was a young, clear-eyed, healthy-cheeked husky. He had been an all-around athlete at Leland University, then had studied law and made the Federal Bureau of Investigation. He was laughing heartily, and applauding. He looked at Ed Race, grinned and said: "Go on, you old clam, why don't you open up and give the boys a hand. I think they're good!"

Ed threw up his hands in despair. "Everybody to his taste," he said. "Some people even like tripe!"

Jimmy Oglethorpe looked at his watch, exclaimed: "Wow! Eleven forty-five, and I've got to meet my regional chief at noon. I got to go, Ed!"

Partages waved to them. "Run along, boys. See you for the afternoon show, Eddie. Remember—your curtain call's at four-fifteen sharp! And I still think the Two Brownies are good."

Ed made a face, pushed Jimmy Oglethorpe up the aisle. In the lobby, a little old lady in a black bonnet was buying two tickets at the Advance Sale window. She had a copy of Variety under one arm, and she was holding the two tickets in her left hand, her big black handbag in her right, and at the same time trying to manage the change of twenty dollars which the cashier was handing her.

Jimmy Oglethorpe gripped Ed Race's arm in sudden excitement, exclaimed under his breath: "Wow!"

Ed gave him a queer look. "Whatsamatter, Jimmy? Your long-lost mother?"

The young F. B. I. man hastily drew Ed Race into a far corner of the lobby. "Listen, Ed," he whispered, "that's a dame that F. B. I. has been looking for all over the country. What a break for me! Look, Ed, I've got to trail her. But I also have to meet my regional chief, Sam Kerwin, in Pennsylvania Station. He's coming in from Washington at twelve o'clock. Be a good guy, Ed, and go down to meet him. Will you?"

Ed nodded. "All right, Sherlock. As long as it's in the nation's service. I've met Kerwin. What'll I tell him—that you're off after a dame?"

"You tell him that I'm on the trail of Mrs. Porter. He'll know what that means. Take him to your hotel, and tell him to wait there for my call. I'll phone in the first chance I get."

Ed caught the edge of Oglethorpe's excitement, and nodded quickly. "Okay, Jimmy. Better get going—she's on her way out."

JIMMY left him, following after the old lady. Ed watched them

for a moment, saw how skillfully Jimmy Oglethorpe faded into the

Broadway crowd behind his quarry. She was moving south on

Broadway, and Ed had to go south, too, so he trailed along down

to the corner. The old lady stopped for a moment, buffered by

the crowd, opened her copy of Variety to an inside page,

tore out an item from an end column, and threw the rest of the

paper in the big waste-paper receptacle alongside the lamp post.

Then she flagged a cab, and Jimmy Oglethorpe got into another,

following her.

Ed Race turned away, walked down another block and entered the subway. At Pennsylvania Station he was just in time to catch the crowd disembarking from the twelve o'clock train.

Sam Kerwin was much older than Jimmy Oglethorpe, with the poise which years of experience bring to the trained manhunter. On the way up to Ed's hotel, they exchanged reminiscences. Kerwin had once been a first-grade detective on the New York Police Force, and had occasion to know Ed Race's peculiar abilities. To the theatre-going public, Ed was known as "The Masked Marksman—The Man Who Can Make Guns Talk." On the stage he performed feats of acrobatics and marksmanship that left the audience breathless at his sheer skill. He juggled with six heavy forty-five calibre, hair-trigger revolvers instead of with Indian clubs, and he could catch those revolvers in midair, fire them at the flames of a row of candles thirty feet across the stage—and put out the flames.

But it was off stage that Kerwin had come to know Ed Race. For Ed's overflowing nervous energy had caused him to seek an avocation that would furnish more excitement than he found in the theatre. That avocation was the detection of crime. He had licenses in a dozen states as a private detective, and his bewildering skill with the two forty-fives that he always carried in his twin shoulder holsters had made his name well-known—and favorably—to the police of dozens of cities; and well-hated by a good slice of the underworld.

So he and Kerwin had much to talk about, and they did their talking over a series of old-fashioneds in the bar of the Longmont Hotel. That is, Ed had the old-fashioneds, while Kerwin drank coffee. It was almost two hours later when Kerwin looked at the time worriedly. "Look here, Ed," he said, "there's something queer about this. Oglethorpe should have called in by this time. That old lady can't be traveling around in taxicabs for two hours; and if she stopped anywhere, Jimmy should have been able to get in a call. I'm worried."

Ed sipped his old-fashioned. "Don't tell me, if it's impertinent, Kerwy, but who is that old lady, anyway?"

Kerwin frowned. "I could get canned for telling you, but what the hell. Mrs. Porter is the mother of a certain bird that's wanted for mail robbery and murder in the Middle West. They call him Teddy 'Slicer.' Heard the name?"

Ed nodded. "Read about it in the papers, that's all. They say he got the name because he slices them in half with a tommy gun."

"That's the one!" Kerwin said grimly. "He isn't satisfied with just killing them; he sprays that typewriter so that his victims are literally cut in half. I've seen the bodies."

"Nice man," Ed commented. "How could he have a mother?"

"He has. We found who she was, but we don't think Teddy Slicer knows that we know. We put a tail on her, hoping that at some time or other her loving son would communicate with her. We drew a blank for ten days, and then suddenly she disappeared. Our man out there got careless, and she slipped right out of sight. That's what I was coming to New York to meet Jimmy for. The country is being combed for her. We figure that where she is, her son will be. I was coming here to work the New York sector. And what happens when I arrive, but you tell me that Jimmy has her spotted already!"

Ed was thoughtful. "You think she came here to join her son?"

"We don't know what to think. She's such a quiet, mouselike old lady that we don't even think she knows what her son is doing. But then, again, we may be all wrong."

Ed finished his old-fashioned. "Look here, Kerwy," he said suddenly, "Jimmy may have walked into something hot. You can't leave this place, because he may call in any minute. All right, you stay here and keep working on your coffee, while I go out and see if I can pick up the trail of the two of them."

Kerwin nodded. "I've got to wait, anyway, because I've phoned for some more agents to meet me here. They'll be arriving in a little while. You call me here in half an hour, whether you have any success or not."

ED left him and took a cab back to the Clyde. His first stop was

at the trash receptacle at the corner, where Mrs. Porter had

thrown her copy of Variety. Surprisingly, it was

empty.

He went into the corner cigar-store and entered a phone booth. He had Kerwin paged in the Longmont bar.

"Any word from Jimmy Oglethorpe yet?" he asked.

"Not a thing, Ed. What have you got?"

"That old lady," Ed told him, "dropped a copy of Variety into the trash can on the corner of Broadway and Forty-sixth. She cut something out of it before she threw it in. The stuff was picked up in a truck before I got here. Can you trace that truck, and have it fished through for the paper? If we can find which clipping she tore out, it may be a lead."

"I'll get right to it," Kerwin told him. "That's an easy one. Call me back after a while."

Ed hung up, went up the street to the Clyde. In the lobby he went over to the Advance Sale window.

"Howya, Mr. Race?" greeted Mabel, the cashier. "Wanna buy a ticket to your own show?"

"Listen, Mabel," Ed said glumly, "about a quarter to twelve, an old lady bought two tickets, and you gave her change of twenty. Remember?"

"Uh-huh. She wore a funny bonnet. Whatsamatter—you think the twenty was phony? It looked good to me. She bought two tickets in the first row balcony for tonight's show."

"Have you got the twenty?"

Mabel fingered through the bills in the drawer, pulled one out. "Here it is—AA1 and AA3. I always mark the seat numbers in pencil on large bills—just in case of a phony."

Ed took the bill, gave her another twenty for it.

The bill was a Federal Reserve Bank note, issued by the Howard National Bank of New York. Ed sighed with relief as he crinkled it, noted that it was brand new. He strode away from the window, leaving Mabel staring after him in perplexity, and went outside, walked two blocks south and a block east, entered the marble precincts of the Howard National Bank.

A man seated at a desk behind the front railing raised a hand in greeting, and Ed went in, plumped down in a chair. "Hello, Mr. Simonson."

"How are you, Race? I meant to talk to you about your account—"

"Not now, Simonson. I'm in a hurry—a hell of a hurry. Will you do me a favor?"

"Of course—but the limit is ten thousand." Simonson chuckled.

Ed put the twenty-dollar bill on the desk. "I'd like to find out to whom this bill was issued. It's damned important."

Simonson said: "Sit here a minute, huh?"

He took the bill, went in back. In a couple of minutes he returned. "This was one of a bundle of twenties issued to one of our depositors, late yesterday."

Ed leaned forward eagerly. "What's the depositor's name?"

Simonson chuckled again. "You can go right back to where you started this morning, Race. It was issued to the Longmont Hotel—where you stay!"

"Hell!" Ed exclaimed. "I was there less than an hour ago!"

The bank official gave him a queer look. "Is this a runaround or something you're giving me, Race? Did you by any chance get that bill at the Longmont yourself, and bring it in to try me out, by any chance?"

"By any chance," Ed told him primly, "I did not. I'll be seeing you, Simonson—and thanks."

He went out wearily, and got in a cab headed for the Longmont on Forty-eighth. He wondered if he was going through a lot of stewing for nothing. Oglethorpe might be quite safe, still tailing the old lady. But if that were so, the origin of the twenty-dollar bill indicated that the old lady must be staying at the Longmont. In which event, Oglethorpe would have tailed her there, and he would surely have been able to contact Ed and Kerwin in the bar. Something must have happened. Either Oglethorpe had lost the old lady, or else—

At the Longmont Ed paid off the driver and went in through the bar. Kerwin wasn't there.

Ed went up to the desk, and the clerk said: "Message for you, Mr. Race. Mr. Kerwin went down to the city incinerator plant. He says you're to wait for a call from him."

"Okay," Ed said. "Now tell me—have you got anybody registered here by the name of Porter—a little old lady in a funny bonnet—"

"Sure. Room 509, right above your room. It's a double, in the name of Mrs. Porter and Miss Brown."

"Five-O-nine, eh? Okay. If Mr. Kerwin calls, connect me with him up there. Give me the key to that room."

"The key? But, say—"

"Lay off the argument!" Ed snapped. "This is a matter of life and death. I've been here long enough for you to know I'm all right. Hand it over, quick!"

The clerk shrugged. "It's all right with me, Mr. Race. I know you're a private dick. Here's the key. Mrs. Porter is out."

"Did anybody call to see her in the last couple of hours?"

"Why, not that I know of. A lot of people just go up without asking at the desk. She came in a while ago, and, come to think of it, she went out only about a half-hour back, with a man."

"Was he a young fellow, athletic?"

"No. He was a pretty stocky chap, heavy built. I just got a quick look. You know I pay little attention—"

"Too little!" Ed murmured.

"Say!" the clerk exclaimed. "Come to think of it, a young fellow like you describe came in right after Mrs. Porter and asked what room she was in. He showed me a badge. I gave him the number, but I don't know if he went up."

"That's enough, Oscar," Ed said hurriedly. He left the clerk, took the elevator up to five-o-nine.

THERE was a "Do Not Disturb" sign on the door, and Ed was

careful not to disturb. He inserted the key very quietly, and

pushed noiselessly into the room. It was the usual

double-room-and-bath of the Longmont, with the layout exactly

the same as Ed's room on the floor below—the bed in the

center of the room, the bathroom opening off the small

foyer.

Ed pushed past the bathroom door, went into the room itself. The shades were all down, and the place was gloomy, but there was enough light to discern what was lying on the bed.

Ed's lips twisted in a grimace of pain, and his eyes assumed a bleak, hard glint. He stepped closer, put out a hand and touched Jimmy Oglethorpe's face. It was still warm, but the feel of death was there. That gesture of Ed's was really not necessary, for it could be seen at a glance that Oglethorpe was dead. He was lying on his back. His coat was wide open, and his natty blue shirt was stained a deep red around the heart. Blood had seeped down from the wound onto the inside of his coat, and through the coat onto the bed.

Ed bent closer, inspected the wound. There were powder burns around it on the shirt. Oglethorpe had been shot at close range. His face was composed, as if he had not expected or anticipated the shot which ended his life.

Ed Race's eyes clouded. He felt a lump in his throat, and he gulped. "God, Jimmy," he murmured, looking down at the youthful face, "you had plenty of life in you yet!"

Abruptly he turned away from the bed, let his eyes wander over the room. The clothes closet was open, showing coats and dresses hung in orderly rows. On a chair near the window were a brassière, a pair of step-ins, and a pair of stockings. On the floor at the foot of the chair was a pair of high-heeled pumps.

Ed noticed two traveling bags, which had evidently been delivered to the Longmont from the railroad station by the Transfer Company. They bore tags reading: "Mrs. Arabella Porter, River City, Wisconsin, to Longmont Hotel, New York." And the other: "Miss Sylvia Brown, River City, Wisconsin, to Longmont Hotel, New York."

Ed didn't touch the bags. He moved through the room, went into the foyer, and opened the bathroom door. A light summer bathrobe was hanging on the hook in the door. A tube of cold cream, with cap off, lay on the washbasin. The bathtub was empty. The shower sheet, however, was drawn across the stand-up shower, built into the wall alongside the tub.

Ed reached over, pulled the shower sheet away, and uttered a gasp of surprise.

A girl was huddled on the floor of the shower. Her skin gleamed white and soft, and she did not stir. She had no clothes at all, and her body was so still that at first Ed though she was dead. He bent closer, heard her steady breathing. Gently he lifted her out. She was not wounded, had just fainted, apparently. Ed put her feet on the cold tile floor, and she suddenly opened her eyes, shrank from him with sudden, instinctive fear.

Ed took down the bathrobe, put it around her, and said: "It's all right, Miss Brown. I won't hurt you."

She snuggled into the bathrobe, stood there small and fragile, the fear slowly fading from her face as she read the kindliness in his eyes.

"Who—who are you?" she asked.

"The name is Race," Ed told her. "I'm a kind of detective."

Suddenly, blind horror took possession of the girl's sensitive face. Her eyes filled with recollection and dread. She moaned: "The dead man! He shot him!" She swayed, and Ed put out a quick hand to steady her. She slumped in his arms.

Ed said crisply: "Come now, Miss Brown, this is no time to faint. You know a man's been killed. Who killed him?"

He felt her slim body quivering in his arms. "Oh God, it—it was terrible. Mrs. Porter's son killed him. He shot him. I—I was in the shower when Mrs. Porter came home, and a few minutes later someone knocked at the door. She opened it, and two men came in. I—I didn't come out, but you can hear everything that's said inside, through the ventilator shaft. One man with a beery voice was saying: 'Keep your mitts in the air, punk!' And then Mrs. Porter cried out: 'My son! What has happened? What are you going to do to this young man?' "

THE girl was still trembling, and Ed patted her on the shoulder.

"Go on, Miss Brown. You're doing all right. Get it over with

quick."

"I—I remember every word they said. The man with the beery voice was snarling. He said: 'Mom, what was the idea of coming to New York? Now you got this punk of a G-Man on my trail!' And Mrs. Porter was crying. She said: 'I saw your picture, son, and wanted to see how you were doing.' Then she asked: 'Why should he be on your trail, son? Have you done wrong?' And the man said brutally: 'Well, you got to know it sometime. I'm wanted for murder. They call me Teddy Slicer. How do you like that, Mom?' Then they talked for a couple of minutes, and I heard the young man arguing with him, and suddenly there was the sound of the shot, and Mrs. Porter screamed: 'You've killed him!' The man with the beery voice laughed, and said: 'Come on, Mom, we got to get out of this. You wouldn't turn your own son in for a murderer—or would you, maybe?'

"After that they were silent for a while, and then I heard them both go out. And then—I must have fainted!"

Ed asked bitterly: "You didn't get a look at this man with the beery voice?"

She shook her head.

"Do you know who he is?"

She hesitated, then said slowly: "God help me, I think I do!"

Ed shook her. "Who?"

But there was no response. She had fainted again. Ed cursed grimly. He lifted her in his arms, started to carry her into the bedroom, then remembered what lay on the bed, and stood in indecision a moment. The telephone inside rang—Ed had to do something with her, so he put her on the floor and placed the bath mat under her head. He went in past the body of Oglethorpe on the bed, and answered the phone. It was Kerwin.

"That you, Race?" said the G-Man. "Say, we found that copy of Variety. How are you doing?"

"Not so well," Ed said quietly. "Can you take it, Kerwin?"

There was a slight pause. "You mean—Jimmy Oglethorpe?"

"Yes, Kerwin."

"Dead?"

"Yes."

There was a long silence. Then from the other end a muted whisper: "God! The poor kid!"

Ed said in a flat voice: "I know how you feel, Kerwin. I feel the same. The kid was a good friend."

"How did he get it, Race?"

"He was shot right here in room 509 of the Longmont. He traced Mrs. Porter here, and her son must have spotted him, and got the drop on him. He brought him in here and killed him. There's a girl here, who heard everything from the bathroom. But she's fainted, and I can't get anything more from her. Porter took his mother out of here."

"You have no idea who or where he is?"

"I have a damn good idea, Kerwin, but I've got to check it first; got to be damned sure. What about that clipping from Variety?"

"There's about three inches torn from the last two columns of page five. I can't get a copy of the paper to see what the item is. We're way out here at the wrong end of Brooklyn. But you buy one and take a look. I'll come right in to the Longmont."

"Make it the Clyde Theatre, Kerwin. I have to go on at four-fifteen. And I'll want you there, if I'm not mistaken."

He waited till Kerwin had hung up, then signaled the operator and said: "Send up Halloran, the house dick."

He went back in the bathroom, tried to revive the girl with water, but failed. She was evidently suffering from severe mental shock.

Halloran came in while he was working over her, and Ed explained the situation to him as briefly as possible.

The redheaded house detective of the Longmont threw up his hands. "Ye gods and little fishes, Race! This is the ninth homicide that's taken place in the hotel since you came to live in it!"

"Lay off," Ed said curtly. "That poor kid was a good friend!"

"Geez, I'm sorry, Race," Halloran said contritely. "I didn't know."

"All right, Halloran. I'm going now. If the girl comes to, try to get her to talk, and phone me at the Clyde. When the homicide men get here, tell them this is an F. B. I. case, and to wait for Kerwin."

DOWN in the lobby, Ed bought a copy of Variety, turned to

page five. The item in the upper corner contained two pictures,

and an announcement that Harry Brown had teamed up with a

partner, to be known as Frankie Brown, and that the two would

appear on the Partages Circuit as the Two Brownies. The pictures

were likenesses of the Two Brownies.

Ed strode out of the hotel, didn't bother with a cab, but walked the short distance to the Clyde. It was without doubt that clipping which had brought Mrs. Porter to New York. According to the girl, Mrs. Porter had said that she had seen her son's picture in the paper. She had bought two tickets to the evening performance. It added up. One of the Browns must be Teddy Slicer. It couldn't be Harry, because his actions for the past ten years were all accounted for.

Ed turned in to the stage entrance of the Clyde, headed back toward the dressing rooms, disregarding the various greetings that were thrown his way. Norma Maitland had the stage, and the audience was giving her a good hand on her first number. Ed looked around but did not see either of the Brownies. He stopped before their dressing room, nudged his shoulder holsters just a bit farther forward, and knocked at the door. There was no answer. He knocked again, harder. A voice growled: "It ain't our cue. What the hell do you want?"

"Can I come in?"

"No!" The voice went on, snapping at someone else in the room: "Lock that door. We don't want no visitors!"

Ed heard a step approaching the door, put a hand to the knob and pushed the door open quickly. He was in the room and had the door shut in a trice, and stood with his back to it facing the tense tableau there. Harry Brown was on his way toward the door to lock it, and stood poised on one foot, stopped in midstride.

In the center of the small room stood the little old lady in the black bonnet. Her face was streaked with the marks of tears, and her narrow shoulders were shrunken so that she seemed to cower. In the corner, seated facing them on the dressing table bench, was Frankie Brown. His thickly jowled face was twisted into an unnatural smile, and his small eyes were fixed on Ed. But Ed was looking at the thing he held in his lap. It was a Thompson submachine gun, and Frankie Brown held it so that it covered the room.

Ed said to him flatly: "You're Teddy Slicer!"

Brown nodded, still smiling twistedly. "That's me, pal. And what might your name be? I always like the names of the guys I'm gonna slice in two."

"The name is Race," Ed told him. "You were certainly a sap to let your picture be taken and printed in Variety." Ed turned to the old lady. "You recognized his picture, didn't you?"

She nodded, her eyes welling once more with tears. "He'd had his face changed, and that was why he wasn't afraid to have his picture printed. But I recognized his eyes—the same eyes his father had. I had to come to New York to see how he was doing in vaudeville. I—I didn't know the Federal men were following me."

Teddy Slicer sneered, shifted a little on the bench so that the muzzle of the Thompson was pointing squarely at Ed's stomach. "I got to go now," he said. "Things is getting too hot around here. The boys are right on my tail. Mom, you go on out."

Mrs. Porter twisted her thin hands. "No, no! Stop these killings. You—"

She stopped, as Teddy Slicer half rose from the bench, snarling. "I said get out! Or do you want to see them get it?"

Ed interrupted mildly: "Excuse me for asking, but how do you figure to get away with a shooting right in the heart of New York?"

The Slicer was leering at him. "I got it all figured out, wise guy. It's so smart, I got to tell somebody, and there's damn few I can talk to nowadays. See, after I slice you birds in two, I'll run outta here and yell: 'Help! They're murderin' my brother!' He ain't my brother, see, but they think he is. Then while everything is upset, I hop a cab to the ferry across Forty-second."

He was beaming at his own cleverness.

Ed beamed back at him. "That's damned clever, Mister Slicer. But pardon me if I ask another question. Do you mind?"

"Go ahead. I like to talk to an intelligent guy like you."

"I just wanted to know why you insist on killing Harry Brown here. He gave you an alibi, took you into the show, made you his partner. You might have been set here, safe from detection, if there hadn't been a fluke. Why do you have to kill him?"

Harry Brown was standing tensely near the door, looking from the Slicer to Ed Race. The Slicer growled: "Sure, he done all that. But he didn't do it because he liked it. He did it because he was afraid for his kid sister. I told him he better fix me up, or I'd slit his kid sister's throat. I made him give out the announcement that he was taking me in as partner, an' then when we started to rehearse for the act it was too late for him to sell me out—he'd have been an accessory. See?"

Ed looked almost unbelievingly at Harry Brown. "You let him bulldoze you like that?"

Harry Brown hung his head. "You see, Ed, he's—legally married to Sylvia. She never took his name. The day after she married him we found out what he really was."

Ed said slowly: "I see."

The Slicer got up from his seat. "All right, Mom, I changed my mind. You get over in that closet. I'll have to lock you in so you can't be tempted to give me away when I run out—"

The old lady drew herself up, wiped the tears from her eyes, and faced the Slicer. "No! You'll have to kill me, too! I—don't—want—to live anymore!" Deliberately, slowly, she started to walk toward him.

The Slicer snarled at her. "Get back! You want me to give it to you, too? Get back, I tell you!" He swung the muzzle of the tommy toward her. And in the split second that the muzzle was moved, while the Slicer's eyes were off him, Ed Race's two hands crossed over his chest with the unbelievable speed of light.

The Slicer's hand was already tautening on the trip of the tommy, pointed at his own mother, when Ed's two guns roared in thunderous rhythm, deafening everybody in the small room, reverberating through the thin partitions out into the backstage section of the theatre.

The Slicer's body was hurled around as if by a cyclone. Great gouts of blood appeared on his chest. Ed's slugs thrust him against the wall, dead before he hit it.

Mrs. Porter was standing, white-faced, with her back to the wall. Harry Brown had stood transfixed, through all the fusillade, right where he had been at the start. Now, as the thunderous echoes of the detonations of the heavy forty-fives died away, Ed said in a tight voice: "I think it's better for your sister to be a widow."

Then he looked at the little old lady. "I'm sorry, Mrs. Porter, that it had to be in your presence—"

She closed her eyes, shook her head slightly. "I had rather it happened this way. It is dreadful for a mother to see her own son shot to death, but I bear you no hate. Indeed, I thank you. Now I can be assured that my flesh and blood shall not be the cause of other deaths!"

There was a loud shouting and hubbub outside the door. Ed flung it open. The crowd gaped into the room, but Ed shooed them away. From the direction of the stage entrance he saw Kerwin and two of his men running toward them.

"All over?" Kerwin said.

Ed nodded silently. For a moment the two men looked into each other's eyes. Kerwin's eyes clouded. Slowly he took off his hat. Ed did likewise. "In respect to a brave man—Jimmy Oglethorpe!" Kerwin murmured.

"And," Ed Race added, turning to gaze into the smoke-filled dressing room at the straight, frail form of Mrs. Porter, "in respect to a very brave lady." He spoke the last words very softly, so that only Kerwin heard him.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.