RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

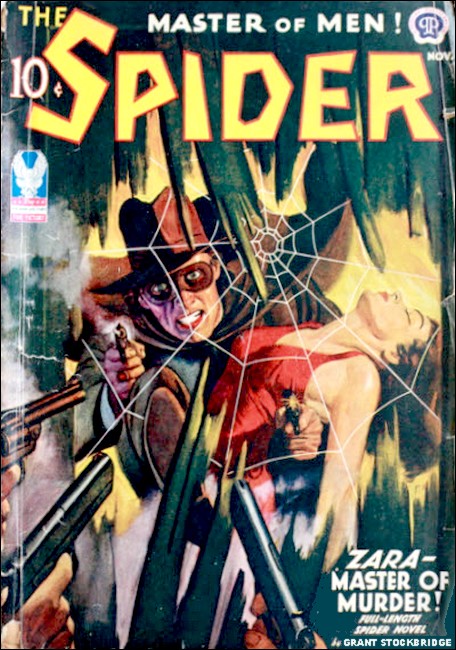

The Spider, November 1942, with "Understudy for Murder"

It seemed odd to Ed Race, vaudeville's beloved Masked Marksman, that a rich girl like Mabel Frisbee should be ghost-writing the biography of a gang chief. But before Ed got through with her employer, and Jarko, and the rat that presaged murder—it was nearly time for Mabel to ghost-write an obituary—for Ed Race!

JARKO came into Ed Race's dressing room at exactly five minutes of nine. He laid the dead rat on the dressing table. Jarko was a big man, but he had a weak chin and watery eyes. His hand was trembling, and there were little glistening beads of perspiration high up on his baldish head.

Ed Race looked at the dead rat, then at Jarko, with equal distaste. He was cleaning his six heavy .45 revolvers. He had just come off the stage, concluding his last performance at the Clyde Theatre for the week.

Ed put down the revolver he was cleaning, and examined the dead rat. Its neck had been broken, apparently in a trap. Its mean little eyes were staring glassily, and its paws stuck straight up in the air.

But it was the tag which was tied around the left front paw by a bit of pink ribbon which drew Ed's attention.

It was a small, oblong tag, such as usually accompanies gift packages. Upon it was neatly typewritten:

THUS PERISH ALL RODENTS!

Ed raised his eyes from the dead rat to the live one.

"Well?" he asked coldly.

Jarko was trembling, and he couldn't stop it. "You know what this m-means, Race?"

Ed shrugged. "Offhand, I'd say it means that some one is going to break your neck."

"It's Visconti!" Jarko blurted. "Everybody knows Visconti sends you a dead rat before he knocks you off!"

Ed raised his eyebrows. He glanced once more at the tag. "That's pretty high-class language for a mugg like Visconti to use. He never got past second grade in grammar school. I bet he couldn't even say those words—let alone typewrite them."

"It isn't Visconti," Jarko told Ed. "It's that ghost writer he's hired himself."

Ed became interested. "Ghost writer?"

"Sure. He got a girl out of the Columbia School of Journalism. Pays her a hundred dollars a week. She's writing his autobiography."

Ed started to laugh. But Jarko began to tremble more than before.

"This is no laughing matter, Race. Lord, I don't want to die!"

"Tell it to the police," Ed advised him unsympathetically.

"I can't. They're down on me. I asked for protection, and they sent me to the District Attorney. But the D.A. won't listen to me. He's sore at me. He said I was no good to society—that I'd be better off dead."

"Hmm," said Ed. "He's a man of great intelligence. But why is he sore at you?"

"Because he was counting on my testimony to convict Visconti yesterday—and the jury acquitted him in spite of it."

"If the jury acquitted Visconti, why is he sending you a dead rat?"

Jarko spread his hands helplessly. "Because I testified against him. He wanted me to get out of town, but the D.A.'s men grabbed me before I could close up the pawnshop. They sweated me all night, and I couldn't stand it. I agreed to testify."

"But your testimony wasn't enough anyway?"

"That's right."

"I see," said Ed. "That's pretty tough. So now you're in Dutch with the D.A.—and with Visconti."

"Will you help me?" Jarko pleaded eagerly.

"Why?" Ed asked. "Name one reason why I should help a man like you."

"I'm a pretty rich man," said Jarko. "I know you don't need money. But I know you're interested in the Actor's Fund. Keep Visconti from killing me, and I'll donate ten thousand dollars to the Actor's Fund."

"Write the check!" said Ed.

Jarko almost fell over himself as he pawed eagerly for his fountain pen and his check book. He spoiled the first check, but he got the second one made out properly.

Ed took the check and put it in his pocket.

"You think you can save me?" Jarko pleaded.

"I don't know," Ed told him. "I'll try. If you're alive one week from today, I'll turn this check over to the Actor's Fund. If you're dead, I'll frame it for a souvenir."

HE took two of his .45 revolvers and slid them into the twin shoulder holsters under his coat. He never went out without those guns, for he had plenty of occasion to use them—off the stage as well as on.

On the stage he had made a name for himself from coast to coast. He was headlined in all the Partages Theatres as: THE MASKED MARKSMAN—The Man Who Can Make Guns Talk.

And indeed, there was little he couldn't do with those hair-trigger .45's. His acrobatic marksmanship number never failed to bring down the house—especially when he sent all six revolvers juggling in the air, went into a back somersault and caught them one by one as they came down—firing each in turn at a row of candles thirty feet across the stage. In twelve years, no one had ever seen him miss one of those candles.

But off the stage he often had to perform even more sensational feats of marksmanship. Few people were aware of the fact that Ed Race had licenses to operate as a private detective in a dozen states. He had made a hobby of criminology, and he never practiced it for pay. But his twin .45's were always at the service of any member of the theatrical profession who found himself at grips with the Underworld.

Jarko watched him as he locked the other four revolvers in the trunk. Then he turned to the trembling pawnbroker.

"I'm going to leave you here," he said. "The shade is down. Lock the door and open to no one but me. You'll be safe enough in this room. Don't go out till I return."

"You don't have to worry," Jarko said. "I'll be here. You couldn't drag me out with wild horses."

Ed made a grimace of distaste, and went out. He heard Jarko click the bolt in the door, and he made his way out of the theatre. At the stage door he said to old Wellington, the doorkeeper, "There's a man in my room. Let him stay there. And be sure not to let anyone in tonight that you don't know."

He walked down to the corner and went into the cigar store and looked up the telephone number of District Attorney Patten's home. In a moment he had the D.A.'s residence, and was lucky enough to find him in.

"Look here, Ted," he said. "I didn't know you were a cold-blooded guy."

"What's this all about, Ed?" Patten demanded.

"It's about your leaving Jarko out in the cold. Do you want Visconti to kill him?"

"Oh, that!" Patten exclaimed. "Well, frankly, I'd like it very much. If Visconti kills Jarko, I'll have an open-and-shut case against him. I've tried for ten years to convict Visconti, and I can't get past a jury. He always has air-tight alibis. But I'd just like to see him murder Jarko!"

"You're deliberately throwing Jarko to the dogs?"

"So what? He's no good. He's a receiver of stolen goods, and a rat. But don't worry. I have Jarko covered pretty well. My men are tailing him night and day, waiting for Visconti to make his move. For instance, I can tell you where Jarko is right at this minute."

"Yes?" said Ed.

"He's in a movie at Fifty-sixth and Broadway. My man tailed him up there, and just phoned me. He's waiting for Jarko to come out, and then he'll stick to him like glue."

"You're wonderful, Ted!" Ed Race told him. "Absolutely marvelous. I don't see how you do it!"

"How I do what?"

"How you manage to remain District Attorney!" Ed growled into the phone, and hung up.

He went out into Broadway again, feeling low. The District Attorney's man must have slipped up, if he thought Jarko was still in that theatre on Fifty-sixth and Broadway. Had Jarko deliberately given the detective the slip? Or had he just gone in to think things over, and then gone out one of the side exits without being spotted by his shadow?

Ed was sorry now that he had taken Jarko's check. But he had it now, so there was nothing to do but follow it up.

He got into a cab and went across to Sixty-first and Eighth Avenue.

THERE was a little two-story building on the side street, with a restaurant and bar on the ground floor, and a single office above. The sign on the restaurant just said: VISCONTI'S. On the plate-glass window of the office above, the lettering read: VISCONTI MACARONI COMPANY.

Ed always got a laugh when he saw that sign. Visconti had never sold an ounce of macaroni in his life. He had started as a youngster, shaking down the business men in the public markets, and he had progressed from that to plain and fancy racketeering, and then on to murder and the higher brackets of crime. Now, from that office upstairs, he controlled all the bookmaking activities in the district. Every corner bookie banked with Visconti. Those who didn't—ended up in the morgue. It was all nice clean business compared to the old days, but it gave district attorneys gray hair, because Visconti was able to beat the rap every time.

Ed went into the restaurant, and at once a couple of torpedoes blocked the doorway. Ed knew them both—Mike Sender and Harry the Goat.

Mike Sender was one of Visconti's collectors during the day, and Harry the Goat was one of the best bouncers and beater-uppers in town. He had got his name from the way he fought. All he'd do was put his head down like a goat and charge in blindly. His head was so hard, that no matter what part of a man's anatomy he hit with it, the fight was over. Harry the Goat's head had had everything broken over it from beer bottles to nightsticks, but nothing had ever made an impression on his skull.

It was Harry who got in Ed's way, but it was Mike who said, "Hello, Mr. Race—and good-by. The boss ain't having any tonight, thank you."

"Now, now, Mike," Ed said. "Don't be like that. I want to talk to Visconti, like one gentleman to another."

"Yeah, sure," said Mike. "Listen, Race, you're the last guy in town I'm looking to tangle with, but I ain't lettin' you upstairs—not after what Jarko told us."

"Jarko?" said Ed. "What did he tell you?"

"He told the boss, that is. Over the phone. He said he was gonna get you to knock the boss off. He was gonna tell you all about the boss being sore at him, and since he had a special drag with you, you'd come here an' make a play which would cause the boss to pull a gat on you, and then you'd burn the boss down."

"Well, I'll be damned!" Ed exclaimed.

"So you see, Mr. Race, it ain't no potatoes. You can't go up."

"I give you my word as a gentleman," Ed said, "that I don't intend to kill Visconti. I just want to talk to him."

"Will you leave your artillery with me?"

"Sure."

"Okay, then—"

Before Mike could finish, Ed's hands had crossed in a streaking motion that was so fast it was almost invisible, and the two revolvers were out of the shoulder holsters and in his hands.

Mike jumped. Harry just stood there, transfixed.

"Hey!" yelled Mike.

Ed merely smiled, and reversed the guns and calmly gave them to Mike Sender.

Mike was sweating. "Jumping goose-pimples! I'd hate to have you gunning for me!"

He went to the house phone, and rang upstairs. He talked for a couple of minutes, with his mouth close to the phone, apparently trying to convince Visconti that it was all right. At last he succeeded. He hung up with a grin.

"It's okay, Mr. Race. I told him I had your gats." He jerked his head at his companion. "Take Mr. Race up to the boss, Harry."

Harry the Goat was still goggle-eyed after witnessing that lightning draw. But he grinned feebly and led the way upstairs. On the upper floor, there was an outer office, and an inner one.

Ed was surprised to see a red-headed girl working at one of the two typewriters in the outer office. She was all alone.

FOR a moment she was unaware that they had come up, and she went on typing. Ed saw that she was young and very pretty. Her profile was clear-cut, her face fresh and youthful, and innocent.

Harry the Goat scraped his feet across the floor, and she stopped typing and looked up.

Harry jerked his thumb at Ed. "To see de Boss," he said. "Mike says it's okay." Then he turned around and clumped down the stairs.

The girl got up from the typewriter, and smiled at Ed.

"I'll tell Mr. Visconti you're here. Name please?"

"Race," said Ed. "Ed Race. What's yours?"

She stopped with her hand on the knob of the door to the inner office. She hesitated, then said, "Mabel. Mabel Frisbee."

"You been working long for Visconti?"

"Only a few days. I'm doing special work. That's why I'm here evenings. You see, I attend school during the day—"

"Journalism?" Ed asked.

"Why, yes. How did you know?"

"I'm a detective," said Ed. "I can tell anybody's occupation by the way they walk."

She went for it, hook, line and sinker.

"Can you really? It must be wonderful to be a detective. I'm interested in crime, you know. That's why I took this job. I'm writing Mr. Visconti's biography."

"Indeed?" said Ed. "Are you being well paid?"

"Oh, yes. I get a hundred dollars a week. But it's not the money. I don't need money. You see—" she blushed a little—"dad's fairly filthy with money. He's worth millions and millions. He thinks it's wonderful that I'm making myself a career in journalism."

Ed's eyes widened. "Your father is Gordon Frisbee, the mining operator?"

"Yes. He has copper mines, and silver mines, and all kinds of mines."

"Does he know you have this job?"

"Yes. I wrote him about it when our instructor told me the job was open. You see, Mr. Visconti asked the Dean to recommend some one, and I was next on the list. The Dean didn't approve of the job, but my dad said okay."

"Your dad approved?"

She nodded brightly. "He said it might make me grow up."

"I think I see what he meant," Ed said drily.

"You see, I promised him that if he'd let me take this job, I'd break off my engagement with Andy Jarko."

Ed jumped. "Andy Jarko?"

"Sure. He's also a student in the School of Journalism."

"Is his father a pawnbroker? Carl Jarko?"

"I don't know what his father does. But that's his father's name—Carl Jarko. Andy and I were going to get married, but I promised dad that if he'd let me take this job, I'd put off marrying Andy till after graduation."

For a minute, Ed couldn't say anything. He felt like a punch drunk fighter groping around in the ring for his opponent.

Just then the door of the inner office opened, and Visconti appeared.

Visconti was a little man, very carefully dressed, with a gardenia in his buttonhole. Ever since he had become successful in his chosen profession, he had also become neat and dapper. His yellow shirt was spotless, and the yellow handkerchief in the breast pocket shone with cleanliness.

He brushed an imaginary speck off his lapel, and said, "Oh, there you are, Race. I was wondering what was keeping you. Mike told me you were on the way up."

"I was just having an interesting conversation with your biographer," Ed said.

Visconti grinned. "Nice idea, huh? My business, a guy can't tell when he'll be cashin' in. So I figures—why not write my life up while the writing is good? Come on in, Race. I don't mind telling you, I'm glad you left them guns downstairs."

Ed started to go in, but stopped and looked at Mabel Frisbee speculatively.

"Tell me, Mabel," he said, "do you ever write poetry?"

"Oh, no," she said. "I specialize in narrative prose. That's why I think I'll do well with Mr. Visconti's biography. It's all action."

"Did you ever write a line like this, Mabel: Thus Perish All Rodents?"

"Why, no," said Mabel. "As I told you, I don't write poetry. And I never heard that line. Who wrote it?"

"That's what I'd like to know!" Ed told her. And he went into Visconti's private office.

Just inside the door, Ed stopped short, and began to chuckle.

IN a chair near the desk, there was a tailor's dummy, just the height and build of Visconti. The dummy was clad in a beautifully cut checked jacket, which was apparently in the process of tailoring, for it still had the tailor's stitches in it. The dummy had no trousers, but a bolt of the same material lay across its knees.

Visconti saw Ed looking at the dummy, and smirked. "I have all my clothes made by Cluett & Hammersmith," he said. "That's a high-class outfit. They charge a century for a suit, an' they got an individual dummy for each customer. They bring up the goods and drape it so I can see just how I'll look. Nice suit, huh? I'll look good in it."

He pushed the dummy and its chair away from the desk, over toward the window, and moved over a chair for Ed to sit on. He himself stayed over near the door.

"Now listen here, Mr. Race," he began. "You got me all wrong. Whatever that rat, Jarko, told you, it's the baloney. I ain't got no bad intentions against him. He thinks I wanna knock him off, but I wouldn't waste lead on a rat like that. Forget it. He ain't in no danger from me."

"I'm glad to hear you say that," Ed told him. "And it's not for Jarko's sake, either. It's for the sake of the Actor's Fund. He gave me a check for ten thousand dollars for the fund, which I can use if he stays alive."

"Haw, haw!" laughed Visconti. "If he gave you a check for ten grand, it'll bounce, take my word for it. He ain't got that much dough. His business is hocked up to the window sills. He was hoping that kid of his would marry the Frisbee girl, but that's out now. She broke the engagement."

Ed said, "Well, there's something smelly—"

He didn't get a chance to finish, for there was a deep-toned explosion somewhere outside, and something whined into the room through the open window.

There was a wicked spat, and the tailor's dummy fell off its chair.

"Holy Hannah!" yelled Visconti. "Somebody's shot my dummy!"

He leaped across toward the window, yanking a gun from a shoulder holster, but Ed Race stopped him, took the gun from his hand and dashed to the window himself.

Down in the courtyard he was just in time to see a dark figure turn the corner into the alley and disappear. He spotted something black lying in the yard, and as his eyes became accustomed to the darkness outside, he made it out to be a revolver.

Slowly he turned around and looked at Visconti. "It's a good thing," he said, "that it wasn't you that was sitting in that chair by the window!"

There was a rush of feet outside, and a banging at the door. Mike's frantic voice came through: "Hey, Boss! Are you all right?"

Visconti snorted in disgust, and went and opened the door. Mike Sender and Harry the Goat came piling through.

Mike saw the gun in Ed's hand, and yelled, "He double-crossed us! He had a gun all the time—"

"Hell, no, you dope!" Visconti barked. "He saved me. I was runnin' for the window, and the guy out there would of seen me an' give it to me. Go down there an' get that gat!"

Harry the Goat hurried down, and returned with the revolver.

Ed took one look at it. "That's mine!" he said. It was one of the four he had locked in his trunk back at the Clyde Theatre.

"Let's take a walk, Visconti," he said. "This is one time when you're on the right side of murder!"

On the way out, Ed looked speculatively at Mabel Frisbee.

"How would you like to come along with us?" he asked. "You may get material for your book."

"Ooh, I'd love it!"

Downstairs, Visconti growled at Mike and Harry, "Stay here, you lugs. Mr. Race is good enough protection for me!"

Ed got into a cab with Visconti and Mabel, and they drove back to the Clyde Theatre.

AT THE stage entrance, Ed asked Wellington if anyone had come out of his dressing room, and Wellington said no. But when he went inside he found the door of his dressing room unlocked.

Jarko was not there. Neither was the dead rat. And the trunk was open. Only three of the four revolvers remained.

"Hmm," said Ed. "He could have got out through the window. It opens on the alley, and it's only a drop of a couple of feet."

Visconti looked at him inquiringly. "Who? Who you talking about, Ed?"

"I'll tell you in a little while," Ed said. Trailed by Visconti and Mabel, he went back to the stage door.

"Did you see a man come in to visit me about nine o'clock?" Ed asked old Wellington. "Carl Jarko?"

"No, sir," said Wellington. "A messenger came with a telegram for one of the actors, and I took it inside, so I was away from the door for about five minutes at that time. And it's funny about that telegram. The actor whom it was for said it must be a mistake. It was from his Aunt May, and he hasn't any Aunt May."

"I see," Ed said thoughtfully.

He went to the public telephone and once more dialed the home of District Attorney Pattern.

"What the hell is it now?" Patten demanded.

"Any late reports on Jarko?" Ed asked, a chuckle in his voice.

"What do you care?"

"Is he still in the movie on Fifty-sixth and Broadway?"

"No, he isn't. As a matter of fact, I just got a call from the man that's tailing him. He came out of the movie, and went to his hockshop. The place was closed, but he opened it up and went inside, and his son, Andrew, joined him a few minutes later. They're both rats, and I hope Visconti gets them both."

"Sometimes," Ed told the D.A., "a rat bites. Especially when it's hungry."

"What are you talking about?" Patten demanded.

"Your man will no doubt give you a further report soon," Ed said, and hung up.

He motioned to Visconti and Mabel. "Follow me."

Outside, he got into another cab and told the driver to take him over to Eighth Avenue, where Jarko's pawnshop was located.

Sure enough, the place was lighted.

Ed had the cab stop a few doors down, and got out.

"Wait here," he told Visconti and Mabel.

Visconti looked puzzled. "What are you figuring for Jarko? You figure it was him that shot my dummy?"

"Could be," said Ed.

"I'll plug the old slob!" Visconti shouted.

"Now wait," Ed urged. "If you do that, you'll be electrocuted, and you'll never finish your biography."

"I never thought of that!" Visconti gasped. "Hell, I'm reforming from now on. No more rough stuff!"

"Attaboy!" said Ed. "Now wait for me."

He left the cab, and walked back toward the pawnshop. He made sure that his two revolvers were loose in their holsters. He had gotten them back from Mike Sender, though Mike had been reluctant to part with them.

In the doorway next to the pawnshop, he spotted the District Attorney's investigator, a fellow named Hogue, whom he knew.

"Hello, Bill," he said. "I hear you're keeping tabs on Jarko."

"Hello, Ed," said Hogue. "Wasn't that Visconti I saw in the cab with you?"

"It was, and it is. But don't worry, Visconti isn't doing any killing tonight. He's a reformed character. He's become an author."

Hogue looked searchingly at Ed. "You been having any drinks tonight?"

Ed laughed. "Take a tip from me. Get around in back, and pick the lock of Jarko's back door. Then listen to what goes on when I'm in there."

Hogue looked doubtful. "You better do it," Ed said. "You're in a bad spot right now, and you don't know it. Jarko gave you the slip tonight, at that theatre on Fifty-sixth Street. He went out for a half hour, and you didn't even know about it."

"You're crazy," said Hogue.

"Did you have your eye on him all during the show?"

"Heck, no. I just waited outside. I wasn't supposed to tail him. I was just supposed to wait for Visconti to go after him."

"All right," said Ed. "That tip still goes. Pick the lock."

"Okay!" Hogue said suddenly. "You never gave us a bum steer before!"

He stepped out of the doorway, and moved down into an alley which would take him to the rear of the pawnshop.

ED waited long enough to give him time to get around in back. Then he sauntered over to the pawnshop door. As he had expected, it was locked. He couldn't see Jarko or his son, but the light told him they were in there, somewhere behind the counter. He raised his fist and began to bang as loud as he could against the door. His idea was to make enough noise to cover up any sound Hogue might make in picking the lock at the rear.

He pounded and kicked at the door for a minute before he saw some one come out from behind the counter. It was Jarko. He came to the door and peered out, and when he saw it was Ed Race he made a face and looked surprised.

"Let me in!" Ed yelled.

"We're closed for business," Jarko yelled back. "We're just here working on the books."

"Let me in," Ed yelled. "It's damned important!"

"Wait a minute," Jarko called back. "I got to get the keys."

He went back behind the counter, and remained there for several minutes, much longer than it should have taken him just to get the keys. Then he came back and unlocked the door. He used only one hand to do it, keeping the other in his jacket pocket.

"What is it you want, Mr. Race?" he asked grouchily.

"Don't you know?" Ed asked.

"I ain't got the faintest idea."

"Didn't you bring me a dead rat and tell me that Visconti was threatening your life?"

Jarko looked at Ed for a full minute. Then he cleared his throat and said deliberately, "I don't know what you're talking about!"

"I see!" Ed said slowly. "You framed me into this thing, all right. You fixed it so Wellington wouldn't see you come into the theatre. You climbed out the window after I'd left, taking one of my revolvers. You even took the dead rat, so I'd have nothing to show. Then you went to Visconti's back yard and waited till I got there. The minute you saw Visconti through the window, you shot him, and left my gun there. Now you're going to claim you never came to see me!"

Jarko's eyes were small and crafty. "Did you say that somebody shot Visconti? Is he dead?"

"What happens to a man when he's shot through the head?" Ed asked.

"Ah!" said Jarko.

"You shot him!" Ed said.

Jarko shook his head. "I'm afraid you're drunk, Mr. Race. I was never in your theatre tonight. I was in the movies, and my son was at a party. He just joined me here."

"Got any proof you were in the movies?" Ed asked.

Jarko smiled craftily. "If proof is necessary, it'll turn up. Good proof, too. Proof that any jury would accept."

"So you're going to frame me with that murder?" Ed asked.

"Why should I murder Visconti?" Jarko demanded.

"I'll tell you why," Ed said. "Because Visconti had taken Mabel Frisbee out of Journalism School, and she had broken her engagement to your son. You had to kill Visconti so Mabel would lose her job, and marry your son. You wanted to marry into her father's millions. You're broke, and that's the only thing that'll save you!"

"Mr. Race," said Jarko, "I think that you are crazy. You killed Visconti yourself. That's it! You killed Visconti, and you are trying to put it on me!"

Ed smiled. "You've forgotten something, Jarko."

The pawnbroker's lips puckered. He looked worried for an instant.

"Forgotten something? What?"

"This!" said Ed. He took out the check for ten thousand dollars which Jarko had given him. "How are you going to explain this to a jury?"

Jarko wet his lips. "Give me that check!"

"Not tonight," said Ed.

JARKO raised his voice. "We'll have to take it away from him, Andy. In the back, Andy. We'll say he came in here and attacked me, and you had to shoot him. Quick, Andy! In the back—"

Ed Race was already in motion. He straight-armed Jarko out of the way and hurled himself into a forward somersault.

It was a trick he had done a thousand times on the stage; but this time his life was at stake.

As he came out of the somersault, his two revolvers appeared in his hand. He caught a glimpse of the baboon-like face of Andy Jarko behind the counter, following him with a long-barreled revolver, waiting for his moving figure to stop so that he could shoot.

Ed's mouth was tight. He was still in motion, coming to his feet out of the somersault and doing a half twist to bring himself around facing Andy. And as he came around, he snapped a shot which caught Andy in the shoulder. The power of that .45 slug knocked the young would-be killer out of the running.

Ed continued the twisting motion, and it brought him around facing Carl Jarko, who had desperately pulled a pistol.

Ed waited an extra second until Jarko could get the automatic all the way out, but the pawnbroker saw Ed's two big guns in his hands, and changed his mind. He let go of the automatic and thrust his hands high in the air.

There was a thrashing sound at the rear of the store, and Hogue came floundering out, tangled in a curtain.

"Damn it!" he wailed. "I heard everything all right, but just when they were gonna shoot you I started to come in, and got all caught up in this curtain!" He glared at Jarko. "You! You're under arrest for attempted murder!" He looked at Ed Race. "Geez! The D.A. will be sore at me! Am I a dope!"

Ed grinned. "I'll tell him you did it."

Just then Visconti came running into the store, with Mabel Frisbee tagging after him. He saw Jarko with his hands in the air, and snorted in disgust. "Yellow!" he said. "Like all rats!"

Mabel Frisbee looked at Andy, who was lying wounded on the floor. "Ooh!" she said. "He's a criminal!" She looked up at Ed, and her eyes became even wider. "And you captured them both! You're a hero! May I—" she came closer to Ed, and turned her eyes up to him—"may I write your biography?"

"Aw, nuts!" Visconti said in disgust.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.