RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"The Song of the Sirens and Other Stories,"

E.P. Dutton & Co., New York, 1919

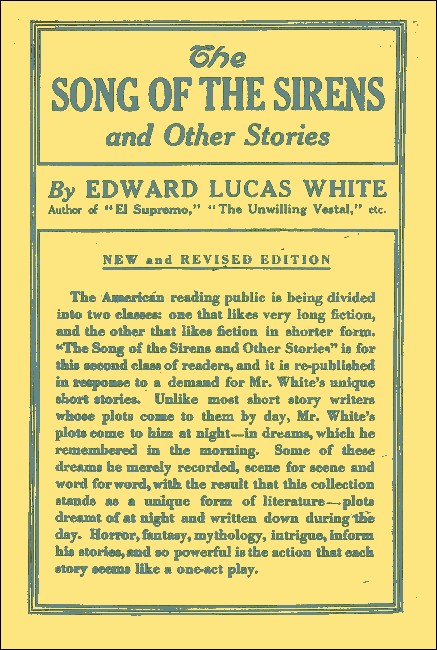

"The Song of the Sirens and Other Stories,"

E.P. Dutton & Co., New York, 1934 Edition

A DAY-DREAMER I have been from boyhood, haunted, no matter what my task, by imaginations, mostly approximating some form of fictitious narrative; imaginations beyond my power to banish and seldom entirely within my power to alter, modify or control.

Besides, I have, in my sleep, dreamed many dreams which, after waking, I could remember: some dimly, vaguely, or faintly; others clearly, vividly or even intensely. A majority of these dreams have been such as come to most sleepers, but a minority have been such as visit few dreamers.

Sometimes I wake with the most distinct recollection of a picture, definite and with a multitude of details. Such was the dream, on the night of February 17th, 1906, in which I saw the vision on which is based the tale of The Song of the Sirens; saw it not as a painted picture, but as if I had been on the cross-trees of a vessel under that intense blue sky, gazing at the magic islet and its portentous occupants. The dream was the more marvelous since there is nothing, either in literature or art, suggesting anything which I beheld in that vision of the two living shapes.

Often I wake with the sensation of having just finished reading a book or story. Generally I can recall the form and appearance of the book and can almost see the last page: size, shape, quality of paper and kind of type; with every letter of the last sentences.

Such a dream was that from which I woke shuddering, tingling with the horror of the revelation at the end of The Flambeau Bracket, with the last three sentences of it, word for word as they stand in the story, branded on my sight. Yet I was not able to recall in its entirety the tale I had just read; for, in the dream, the whole action took place on the window-sill, and what was done and said there disclosed all that had gone before and implied, unmistakably, all that was to come after. This superlative artistry I could not attain to in writing the tale.

It has happened that I have dreamed the same dream over and over. Some of these recurrent dreams have repeated themselves many times; a few have recurred at intervals varying from a few nights to many months over periods running into years. The story called Disvola is told almost exactly as I dreamed it; the ending, from getting my eyes above the level of the window-sill, once only, on the night of February 20th, 1911; the earlier portion as I dreamed it, sometimes twice weekly, sometimes once in six months or so, over a period of more than twelve years, from early in 1899. Three or four times the dream began with my escape from the massacre of my company by turning on my pursuers in the wood and killing the foremost: generally, however, it began when I woke in the dark in the dream and saw the light twinkling far away across the valley; I, in the dream, recalling all that had gone before. No existent path which my living feet have trod is better known to me than that dream-path from my hiding-place, down to the river-ford and up to the castle-wall; especially the latter part which, in the dream, I knew already by touch from my memories of my youthful acquaintance with it.

During the twelve years throughout which this dream recurred to me my waking meditations dwelt often on conjectures as to what I should find inside that window, if ever I got inside it. But, after all that pondering, the climax of that dream amazed me even more than the climax of the tale will probably startle a sensitive reader. I, in my dream, did not read it; it happened to me. The diabolical ingenuity of it still gives me spinal intuitions.

In many of my dreams I have noted that, while dreaming, I seem to retain no trace of my waking individuality. In this dream I knew nothing, in respect to food, clothing, housing or any other of the circumstances of life, beyond what would have been known to an Italian condottiere of the fourteenth century. As the dream recurred I came to recognize it for a dream and, while experiencing it in my dream-personality, was able to look on, as it were, in my own personality and con the whole. I was over and over impressed with the entire absence of any feature inappropriate to the locality and period in which the dream seemed to belong, and struck with the uncanny raciness of the Italian in what was said to me. I never could, after waking, recall more than a word or two; but I retained and retain a distinct impression of knowing vastly more Italian in that dream (as in many other dreams) than I know in my proper person.

Stevenson, somewhere, writes of dream-words and of the warped and enhanced significance which real words take on in dreams. So in this. "Bauro," as far as I know, is no Italian name, nor an Italian word, at all. In the dream it appeared, somehow, a well-known dialectic variant of "paura," "fear," and seemed to imply Bauro's ferocity and the dread which he inspired universally.

The title of this tale is taken from a dream wholly unrelated to the dream of this story, a dream in which I was being shown portfolios of etchings and others of cheap reproductions of the same etchings; my mentor, talking Italian, saying of the reproductions:

"Non sono tavole, sono disvole."

In the dream these words meant: "These are not pictures, merely near-pictures." Now "tavola" in Italian is used of no kind of picture except an altar-piece, and "disvola" is not Italian at all, merely a dream-word. Which is just the way in which words behave in dreams, as Stevenson noted.

The six tales which follow the first in this collection are, I believe, veracious glimpses of the past, without any marring anachronisms. But The Skewbald Panther is a product rather of creative impulse than of ripe scholarship. It is, however, to my thinking, too good a story to be spoiled in an attempted rewriting. Accurate later knowledge does not lure me to alterations. The tale's plot pivots on my fantastic youthful misconceptions as to seating-regulations in the Colosseum; and these, while wholly baseless and infinitely improbable, are by no means impossible nor are they out of key with the period-atmosphere; which atmosphere, both social and conversational, is, I believe, veraciously conveyed.

—Edward Lucas White.

I FIRST caught sight of him as he sat on the wharf. He was seated on a rather large seaman's chest, painted green and very much battered. He wore gray, his shirt was navy-blue flannel, his necktie a flaring red bandana handkerchief knotted loosely under the ill-fitting lop-sided collar, his hat was soft, gray felt and he held it in his hands on his knees. His hair was fine, straight and lightish, his eyes china-blue, his nose straight, his skin tanned. His features were those of an intelligent face, but there was in it no expression of intelligence, in fact no expression at all. It was this absence of expression that caught my eye. His face was blank, not with the blankness of vacuity, but with the insensibility of abstraction. He sat there amid the voluble negro loafers, the hurrying stevedores, the shouting wharf-hands, the clattering tackles, the creaking shears and all the hurry and bustle of unloading or loading four vessels, as imperturbable as a bronze statue of Buddha in meditation. His gaze was fixed unvaryingly straight before him and he seemed to notice and observe more distant objects; the larger panorama of moving craft in the harbor, the fussy haste of the scuttling tugboats tugging nothing, the sullen reluctance of the urged scows, the outgoing and incoming pungies and schooners, the interwoven pattern they all formed together, the break in it now and again from the dignified passage of a towed bark or ship or from the stately progress of a big steamer. Of all this he seemed aware, but of what went on about him he seemed not only unaware but unconscious, with an impassivity not as if intentionally aloof nor absorbingly preoccupied but as if utterly unconscious or totally insensible to it all. During my long, fidgety wait that first morning I watched him at intervals a good part of the time. Once a pimply, bloated boarding-master, patrolling the wharf, stopped full in front of him, caught his eye and exchanged a few words with him, otherwise no one seemed to notice him, and he scarcely moved, bare-headed all the while in the June sunlight. When I was at last notified that the Medorus would not sail that day, went over her side, and left the pier, I saw him sitting as when I first caught sight of him.

Next morning I found him in almost the same spot, in precisely the same attitude, and with the same demeanor. He might have been there all night.

Soon after I reached the Medorus the second morning the bloated boarding-master came on board with that rarity, a native American seaman. I was sitting on the cabin-deck by the saloon-skylight, Griswold on one side of me and Mr. Collins on the other. Captain Benson, puffy, pasty-faced and shifty-eyed, was sitting on the booby-hatch, whistling in an exasperatingly monotonous, tuneless and meaningless fashion. As soon as the Yankee came up the companion-ladder he halted, turned to the boarding master who was following him and blurted out.

"What! Beast Benson! Me ship with Beast Benson!" And back he went down the ladder and off up the pier.

Benson said never a word, but recommenced his whistling. It was part of his undignified shiftlessness that he aired his shame on deck. Almost any captain, fool or knave or both, would have kept his cabin or sat by his saloon table. Benson advertised his helplessness to crew, loafers and passers by alike.

The boarding master walked up to Mr. Collins and said:

"You see, Sir. I can't do anything. You're lucky enough to be only two hands short for a crew and luckier to have gotten a second mate to sign. Wilson's the best I can do for first mate. He's willing and he's the only man I can get. Not another boarding-master will so much as try for you."

Mr. Collins kept his irritating set smile, his mean little eyes peering out of his narrow face, his stubby scrubbing-brush pepper-and-salt mustache bristling against his nose. He made no reply to the boarding-master but turned to Griswold.

"You're a doctor, aren't you?" he queried.

"Not yet," Griswold replied.

"Well," said Mr. Collins impatiently, "you know pretty much what doctors know?"

"Pretty much, I trust," Griswold answered cheerfully.

"Can you tell whether a man is deaf or not?" Mr. Collins pursued.

"I fancy I could," Griswold declared, gaily.

"Would you mind testing that man over there for me?" Mr. Collins jerked his thumb toward the impassive figure on the seaman's chest.

Griswold stared.

"He looks deaf enough from here," he asserted.

"Try him nearer," Mr. Collins insisted.

Griswold swung off the cabin deck, lounged over to the companion ladder, went down it leisurely and sauntered toward the seated mariner. Griswold had a taking way with him, a jaunty manner, an agreeable smile, a charming demeanor and plenty of self-confidence. He usually got on immediately with strangers. So now you could see him win at once the confidence of the man. He looked up at him with a sentient and interested personal glance. They talked some little time and then Griswold sauntered back. He did not speak but seated himself by me as before, lit a fresh cigarette and smoked reflectively.

"Is he deaf?" Mr. Collins inquired.

"Deaf is no word for it," Griswold declared, "an adder is nothing to him. I'll bet he has neither tympanum, malleus, incus nor stapes in either ear, and that both cochleas are totally ossified; that the middle ear is annihilated and the inner ear obliterated on both sides of his head. His hearing is not defective, it is abolished, non-existent. I never saw or heard of a man who impressed me as being so totally deaf."

"What did I tell you?" broke in Captain Benson from the booby-hatch.

"Benson, shut up," said Mr. Collins. Benson took it without any change of expression or attitude.

"You seemed to talk to him," Mr. Collins said to Griswold.

"He can read lips cleverly," Griswold replied. "Only once did I have to repeat anything."

"Did you ask him if he was deaf?" Mr. Collins inquired.

"I did," said Griswold, "and he told the truth instanter."

"Impressed you as truthful, did he?" Mr. Collins queried.

"Notably," Griswold said. "There is a gentlemanly something about him. He is the kind of man you respect from the first, and truthful as possible."

"You hear that, Benson?" Mr. Collins asked.

"What's truthfulness of a pitch-dark night in a gale of wind!" Benson snorted. "The man's stone deaf."

Mr. Collins flared up.

"You may take your choice of three ways," he said, "the Medorus tows out at noon. If you can find a first-mate to suit you by then, or if you take Wilson as first-mate, you take her out. If not, I'll find another master for her and you can find another ship."

Benson lumbered off the booby-hatch and disappeared down the cabin companion-way. The cabin-boy came up whistling, went briskly over the side, and scampered some little distance up the pier to where three boarding-masters stood chatting. One of them came back with him, three or four half sober sailors tagging after him. These he left by the deaf man's sea-chest. Its owner came aboard with him and together they went down into the cabin.

"Look here, Mr. Collins," I said, "I've half a mind to back out of this and stay ashore?"

"Why?" he queried, his little gray eyes like slits in his face.

"I hear this captain called Beast Benson, I see he has difficulty in getting a crew and before me you force him to take a deaf mate. An unwilling crew, a defective officer and an unpopular captain seem to me to make a risky combination."

"All combinations are risky at sea, as far as that goes," said Mr. Collins easily. "Most crews are unwilling and few captains popular. Benson is not half a bad captain. He always has bother getting a crew because he is economical of food with them. But you'll find good eating in the cabin. He has never had any trouble with a crew, once at sea. He is cautious, takes better care of his sails, rigging and tackle than any man I know, is a natural genius at seamanship, humoring his ship, coaxing the wind and all that. And he is a precious sharp hand to sell flour and buy coffee, I can tell you. You'll be safe with him. I should feel perfectly safe with him. I'm sorry I can't go, I can tell you."

"But the deaf mate," I persisted.

"He has good discharges," said Mr. Collins, "and is well spoken of. He's all right."

At that moment the boarding-master came out of the cabin and went over the side. Two of the sailors picked up the first-mate's chest and it was soon aboard. The two men went down into the cabin to sign articles. As they went down and as they came up I had a good look at them. One was a Mecklenburger, a lout of a hulking boy, with an ugly face made uglier by loathsome swellings under his chin. The other was a big, stout Irishman, his curly hair tousled, his fat face flushed, his eyes wild and rolling with the after-effects of a shore debauch. His eyes were notable, one bright enamel-blue, the other skinned-over with an opaque, white, film. He lurched against the companion-hatch, as he came up, and half-rolled, half-stumbled forward. He was still three-quarters drunk.

The Medorus towed out at noon. Mr. Collins and Griswold stayed aboard till the tug cast loose, about dusk. After that we worked down the bay under our own sail. Even in the bay I was seasick and for some days I took little interest in anything. I had made some attempt to eat, but beyond calling the first-mate Mr. Wilson and the second mate Mr. Olsen, my brief stays at table had profited me little. I had brought a steamer-chair with me and lolled in it most of the daylight, too limp to notice much of anything.

I couldn't help noticing Captain Benson's undignified behavior. A merchant captain, beyond taking the sun each morning and noon and being waked at midnight by the mate just off watch to hear his report, plotting his course on his chart and keeping his log, concerns himself not at all with the management of his ship, except when he takes the wheel at the critical moment of tacking, or of box-hauling, if the wind changes suddenly, or when a dangerous storm makes it incumbent upon him to take charge continually. Otherwise he leaves all routine matters to the mate on watch. Benson transgressed sea-etiquette continually in this respect. He was forever nosing about and interfering with one or the other mate in respect to matters too small for a self-respecting captain's notice. His mates' contempt for him was plain enough, but was discreetly veiled behind silent lips, expressionless faces and far-off eyes. The men were more open and exchanged sneering glances. The captain would sit on the edge of the cabin-deck, his feet dangling over the poop-deck, and continually nag the steersman, keeping it up for hours.

"Keep her up to the wind," he would say, "keep that royal lifting."

"Aye, aye, Sir," would come from the man at the wheel.

Next moment the captain would call out:

"Let her go off, you damn fool. You'll have her aback!"

"Let her go off, Sir," the victim would reply.

Presently again Benson would snarl:

"Where are you lettin' her go to? Keep her up to the wind."

"Keep her up to the wind, Sir," would come the reply and so on in maddening reiteration.

A day or two after we cleared the capes the big one-eyed Irishman had the wheel. His name, I found afterwards, was Terence Burke and he was from Five Rivers, Canada. He had been a mariner all his life; knew most of the seas and ports of the world. He was especially proud of having been in the United States Navy and of his Civil War record. He had been one of the seamen on the Congress or the Cumberland, I forget which, and graphic were his descriptions of his sensations while the Merrimac's shells were tearing through the helpless ship, the men lying flat in rows on the farther side of the decks, and the six-foot live-oak splinters, deadly as the bits of shell themselves, flying murderously about as each shell burst; of how they took to their boats after dark, and reached the shore, expecting to be captured every moment; of how they saw the Ericsson's lights (Burke always called the Monitor the Ericsson) coming in from the sea, and took heart. Burke was justly proud that he had been one of the men detailed, as biggest and strongest, to work the Ericsson's guns, and that he had helped fight her big turret guns in her famous first battle.

All this about Burke I did not learn till many days later. But it was plain to be seen, even by a sea-sick land-lubber, that he was an able seaman, seasoned, competent and self-respecting. All that was manifest all over him as he stood at the wheel. Likewise it was plain that he had brought liquor aboard with him, for he was still half-drunk, and quarrelsome drunk. Even I could see that in his attitude, in his florid face, in his boiled eye. But Captain Benson did not see it when presently he came on deck and seated himself on the edge of the cabin-deck. He cocked his eye up the main-mast and presently growled.

"Let her go off."

Burke shifted the wheel a quarter of a spoke, his jaws clenched, his lips tight shut.

Benson chewed on his big quid and kept his eye aloft. Again he growled:

"Keep her up to the wind."

Burke shifted the wheel back a quarter of a spoke, again without any word.

"Till learn ye sea-manners," Benson snarled. "I'll learn ye to repeat after me what I say. Do ye hear me?"

"Aye, aye, Sor," Burke replied, smartly enough.

Shortly Benson came at him again.

"Let her go off, you damn fool."

"Let her go off, you damn fool, Sor," Burke sang out in a rasping Celtic roar which carried to the jib boom.

It was Olsen's watch and the big Norseman was standing by the weather-rigging, his hand on one of the main shrouds. He grinned broadly, full in Captain Benson's face and then looked away to windward. Burke was clutching the spokes as if he were ready to tear them out of the wheel. He looked fighting mad all over. Captain Benson looked aft at him, looked forward, looked aloft, and then rose and went below without a word. Henceforward he worried the steersman no more, unless it were Dutch Charlie, the big loutish boy with the ulcerated chin, or Pomeranian Emil, a timid Baltic waif. Burke and the other full-grown men he let alone.

Next day Burke looked drunker and more belligerent than ever. I noted it, even in my half-daze of flabby nauseated weakness, which subdued me so totally that not even a beautiful and novel spectacle revived me. It was just before noon. The captain and the first-mate had come on deck with their sextants to determine our latitude. The day was fine with a gentle steady breeze, a clear sky and unclouded sunlight, over all the white-capped blue waters. Smoke sighted a little before turned out to be that of a British man-of-war. Just as the captain told the man at the wheel to make it eight-bells, the man-of-war crossed our bows, all white paint and gilding, her ensign spread, flags everywhere, her band playing and her crew manning the yards. The cabin-boy said it was an English bank-holiday, and that she was bound for Bermuda. I was too flaccid to ask further or to care. I made no attempt to go below for the noon meal. I lay at length in my chair. While the captain and mates were at their dinner I could hear loud voices from the forecastle, or perhaps round the galley door. Presently the first-mate came on deck. He walked to starboard, which was to windward, and stood staring after the far off smoke of the vanished man-of-war. He was a tall, clean-built square-shouldered man, English in every detail of movement, attitude and demeanor. He interested me, for in spite of his expressionless face he looked far too intelligent for his calling. I was watching him when I was aware of Burke puffing and snorting aft along the main deck. He puffed and snorted up the port companion-ladder to the poop-deck. His face was redder than ever and his eyes redder than his face. He carried a pan of scouse or biscuit-hash or some such mess. He approached the first-mate from behind and hailed him.

"Luke at thot, Sor," he said, "uz thot fit fude fur min?"

The mate, unaware of his presence, did not move or speak.

"Luke at thot Oi say," Burke roared, "uz thot fit to fade min on?"

The mate remained immobile.

Burke gave a sort of snarling howl, hurled at the mate the pannikin, which hit him on the back of the head, its contents going all over his neck and down his collar. As he threw it Burke leaped at the officer. He whirled round before he was seized and met the attack with a short, right-hand jab on Burke's jaw. There was not enough swing in the blow to down the sailor. He clutched both lapels of the mate's open pea-jacket and pulled him forward. The force the mate had put into the blow, and the impetus it had imparted to Burke, besides his sideways wrench, took the mate half off his feet. He got in a second jab, this time with his left hand, but again too short to be effective. Both men lurched toward the booby-hatch and the inside breast-pockets of the mate's jolted jacket cascaded a shower of letters upon the deck, which blew hither and thither to port. My chair was on the cabin-deck just above the port companion-ladder. The booky man's instinct to save written paper shook me out of my lethargy. In an instant I was out of my chair, down the ladder and picking up the scattered envelopes. Not one, I think, went over-board. I saved three by the port rail and a half a dozen more further inboard. As I scrambled about from one to the other I glanced again and again at the men struggling on the other side of the booby-hatch. The mate had not lost his footing. His short-arm jabs had pushed Burke back till he lost hold of the pea-jacket. The Irishman gathered himself for a rush, the mate squared off, in perfect form, met the rush with a left-hand upper cut on the seaman's chin, calculated his swing and planted a terribly accurate right-hand drive full in Burke's face. He went backward over the starboard companion-ladder down into the main deck.

Paying no more attention to him the mate turned to pick up his letters. He found several on the deck against the booby-hatch, and one by the break of the cabin. Then he looked about for more. I stepped unsteadily toward him and handed him those I had gathered up. In gathering them it had been impossible for me to help noting the address, and the stamps and the post-marks, which on several were English, on two or three French, on two Italian, on one German, on one Egyptian and on one Australian. The address the same on all, was:

Geoffrey Cecil, Esq.

c.o. Alexander Brown & Son

Baltimore, Maryland,

U. S. A.

Instinctively I turned the packet face down as I handed it to him. He took it gracefully and in his totally toneless voice said:

"Thank you very much."

As he said the words Captain Benson appeared in the cabin companion-way, his revolver in his hands. The mate in the act of stowing with his left hand the letters in his inner breast-pocket, pointed his extended index finger at the pistol.

"Put that thing away!" he commanded.

The voice was as toneless as before, but far otherwise than the blurred British evenness of his acknowledgment to me, these words rang hard and sharp. Benson took the rebuke as if he had been the mate and the other his captain, turned and shuffled fumblingly back down the companion-way. As he passed the pantry door the cabin-boy whipped out of it and popped up the companion-way to see, and the big Norse mate emerged deliberately behind him.

By this time the fat negro steward and most of the crew had come aft and gathered about the prostrate Burke.

The first-mate cleared the scouse from his neck and collar, took some tarred marline from an outside pocket of his pea-jacket, and in a leisurely way went down into the waist. He had the men turn Burke over and tie his hands be hind him and his ankles together. Then he had buckets of sea-water dashed over him. Burke soon regained consciousness.

"Carry him forward and put him in his bunk," the mate commanded. "When he says he will behave cut him loose."

Captain Benson had come on deck and was standing by the booby-hatch.

"That man ought to be put in irons," he said as the mate turned.

The mate's eyes were on his face as he said it.

"He needs no irons," he retorted crisply. "Why make a mountain out of a mole-hill."

I had been hoping that I was getting used to the sea, for I was only passively uncomfortable and mildly wretched. But sometime that night it came on to blow fresh and I waked acutely sea-sick and suffering violently from horrible surging qualms in every joint. I clambered out of my bunk, struggled into some clothes and crawled across the cabin and up the after companion-way to the wheel-deck. There I collapsed at full length into four inches of warm rain water against the lee-rail. At first the baffling breeze was comforting after the stuffy cabin, smelling of stale coffee, damp sea-biscuit, prunes, oilskins and what not. But I was soon too cold, for I was vestless and coatless, and before long my teeth were chattering and I had a general chill to add to my misery. It was the first-mate's watch and coming aft on his eternal round he found me there. He at once went below and brought me not only vest and jacket but my mackintosh also. I was wet to the skin all over, but the mackintosh was gratefully warm. Forgetting that he could not hear I thanked him inarticulately, and relapsed into my shifting pond, where I slipped into oblivion, my head on the outer timber, the tearing dawn-wind across my face.

SOMETIME before noon I was again in my chair, as on the day before, and it was again the first-mate's watch. Again I saw Burke come aft. He was not puffing and snorting this time, but very silent. His florid face was a sort of gray-brown. His head was tied up and the bandage tilted sideways over his bad eye. He came up to port companion ladder half way from the waist of the poop-deck. There he stood holding on to the top of the rail, looking very humble and abashed. It was some time before the first-mate noticed him or deigned to notice him. In that interval Burke said a score of times:

"Mr. Willson, Sor."

Each time he realized that he was ignored he waited meekly for a chance to try again. Finally the mate saw him speak and asked:

"What is it, Burke?"

Burke began to pour out a torrent of speech.

"Come here," said the mate.

When Burke was close to him he said:

"Speak slow."

"Shure Sor," he said, "ye wudn't go fur to call ut mut'ny whan a man's droonk an' makes a fule of himsilf?"

"Perhaps not," the mate replied, his steady eyes on Burke's face.

"Ye, wudn't, I know," Burke went on confidently. "Ye see, Sor, Oi was half droonk whan Oi cum aboord. An' Oi had licker tu, more fule Oi. Mr. Olsen, he cum forrard in the dog-watch afther ye'd taat me me place, and he routed ut out an' hove ut overboord. Oi'm sobered now Sor, with the facer ye giv me an' the cowld wather an' the slape, Oi'm sobered, an' Oi'm sobered for the voyage, Sor. Ye'll foind me quoite and rispectful Sor. Oi was droonk Sor, an' the scouse misloiked me, an' Oi made a fule ov mesilf. Ye'll foind me quoite and rispectful, Sor, indade ye wull. Ye wudn't go for to log me for mut'ny for makin' a fule ov mesilf Sor, wud ye now, Sor?"

"No, Burke," said the mate. "I shall not log you. Go forward."

Burke went.

SOME DAYS later I was forward on the forecastle deck, ensconced against the big canvas-covered anchor, leaning over the side and watching the foam about the cut-water and the upspurted coveys of sudden flying fish, darting out of the waves, at the edge of the bark's shadows and veering erratically in their unpredictable flights. Burke, barefoot and chewing a large quid, was going about with a tar-bucket, swabbing mats and other such devices. He approached me.

"Mr. Ferris, Sor," he said, "ye wudn't have a bit of washin' a man cud du for ye? Ye'll be strange loike aboord ship, an' this yer foorst voyage, an' ye the only passenger, an' this a sailin' ship, tu. Ye'll be thinkin' ov a hotel, Mr. Ferris, Sor. An' there's no wan to du washin' here fur ye, Sor. The naygur cuke is no manner ov use tu ye. Ye giv me anny bits ye want washed an Oi'll wash 'em nate fur ye. A man-o-war's man knows a dale ov washin' an' ye'll pay me wut ye loike. Thin I'll not be set ashore in Rio wudout a cint, Sor."

"You'll have your wages," I hazarded.

"Not with Beast Benson," he replied, "little duh ye know Beast Benson. Oi know um. Wut didn't go into me advances ull go into the shlop-chest. Oi may have a millrace or maybe tu at Rio, divil a cint moor."

This was the beginning of many chats with Burke. He told me of Five Rivers, of his life on men-of-war, of his participation in the battle between the Merrimac and the Ericsson, as he called the Monitor, of unholy adventures in a hundred ports, of countless officers he had served under.

"An' niver wan uz foine a gintlemin uz Mr. Willson," he would wind up. "Niver wan ov them all. Shure, he's no Willson. He ships as John Willson, Liverpool. Now all the seas knows John Willson ov Liverpool. There's thousands ov him. He's afloat all over the wurruld. He's always the same, short and curly-headed, black-haired and dark-faced, ivery John Willson is loike ivery other wan. Ivery Liverpool Portugee uz John Willson whin he cooms to soign articles. But Mr. Willson's no Dago, no Liverpool man at all. He's a gintlemin, British all over, an' a midlander at thot an' no seaman be naature at all. But he's the gintlemin. Ye saa him down me. He's the foine gintlemin. Not a midshipman or liftenant did iver Oi see a foiner gintlemin than him, and how sinsible he uz. Haff the officers Oi've served under wuz lunies, sinsible on this or thot, but half luny on most things and luny all over on this or thot. But Juke at Mr. Willson. Sinsible all over he uz, sinsible all thru. Luke at the discipline he huz. An' no wunder. Luke at huz oi! He cudn't du a mane thing av he wanted tu, he cudn't tell a loi av he throid, thrust me Soi, Oi know, the min knows. It's loike byes at skule wid a tacher, or min in the army wid their orficers. You can't fule thim, they knows, an' wull they knows a man whin they say wan. Oi'd thrust Mr. Willson annywhere and annyhow. So wud anny other sailor man or anny man. Deef he uz, deef as an anchor fouled on a rock bottom. But he hears wid huz eyes, wid huz fingers, wid the hull skin av him. He's all sinse an' trewth an' koindness."

Not any other of the sailors besides Burke did I find sociable or communicative or capable, apparently, of intelligent intercourse. Of the captain I saw and heard enough, and more than enough, at meal times. He deserved his nickname and I avoided him with detestation.

The second mate, a big Norwegian named Olaf Olsen, was a kindly soul, but dull and uncommunicative. He had a companionable eye, but felt neither any need of converse nor any promptings toward it. Speech he never volunteered, questions he answered monosyllabically. One Sunday indeed he so far unbent as to ask if he might borrow one of my books. I told him I doubted if any would please him. He looked them over disappointedly.

"Have you any books of Doomuses?" he queried.

"Doomus?" I repeated after him reflectively.

"You're a scholar, aren't you?" he demanded.

"I aim to be," I said.

"How do you pronounce, D-u-m-a-s?" he inquired.

"I am no Frenchman," I told him, "but Dumas is pretty close to it."

"That's what I said," he shouted, "and they all laughed at me and said 'Doomus, ye damn fool.' Have you any of his books?"

"No," I confessed and he ceased to regard me as worth borrowing from.

Not so Mr. Wilson. Before we ran into the doldrums I had found my sea-legs and exhausted the diversion of learning the name of every bit of rope, metal and wood on the bark, and also the amusement of climbing the rigging. I settled down to luxurious days of reading. The first Sunday afterwards Mr. Wilson asked for a book. I took him into my cabin and showed him my stock, one-volume poets mostly, the Iliad, the Odyssey, the Greek Anthology, Dante, Carducci, Goethe, Heine, Shakespeare, Milton, Shelley, Keats, Tennyson, Browning, Swinburne and Rosetti, and a dozen volumes of Hugo's lyrics. I watched him as he conned them over and thought I saw his eyes light over the Greek volumes, thought I saw in them both desire and resignation. He took Milton to begin on and afterwards borrowed my English books in series. I believe he read each entire, certainly he read much during his watches below.

At first I felt equal only to the English myself. But after we entered the glorious south-east trades, I read first Faust, then the Divina Comedia, then the Iliad, and, as our voyage neared its end gave myself up to the delights of the Odyssey.

Meanwhile I had come to feel very well acquainted with the deaf mate. Generally we had spent part of each fair Sunday in conversation. He read lips so instantly and accurately that if I faced the sun and he was close to me we talked almost as easily as if he had heard perfectly. The conversations were all of his making. He was not a man whom one would question, whereas he questioned me freely after he had made sure, but very delicately managed tentative beginnings, that I did not at all object to being questioned. He was a little stiff at first, half timid, half wary. When he found in me no disposition to intrude upon his reserve, and felt my manner untinged by either condescension, which I did not feel, or curiosity, which I sedulously repressed, he surrendered himself somewhat to the pleasure of exchanging ideas as an equal with a man of his own kind. We came to an unspoken understanding and talked openly on a level footing as two men of education, as two aspirants after culture. He relaxed his caution sufficiently to discard any concealment of his attainments and we discussed freely not only my books which he had borrowed but also whatever I had in hand. He never let slip anything which could tell me whether his spiritual background had been Oxford or Cambridge, yet I knew that only at one or the other could he have developed the mind he revealed.

Toward the end of the voyage our day-time chats usually began with his asking what I was reading. Even in the midst of the steady routine of his unremitting seamanly diligence he often paused by my chair on a week-day and delighted me with a brief talk which I enjoyed as much as he. Our Sunday talks came to take up much of his deck-watches. But what most delighted me was to listen to his monologues at night. Monologues they were, for I could neither interrupt nor reply. He would begin his watch by a double turn round the bark, twice speaking to the steersman, twice to the lookout. Then he would pace the poop-deck, just aft of the break; from rail to rail. As he turned by the lee rail he would throw a comprehensive glance over the whole spread of the bark's canvas, so he turned by the weather rail he would stoop down, peer out under the mainsail and sweep his eyes along the horizon on our lee bow. In the early part of our voyage I had watched him night after night keep this up for an entire watch, evenly as an automaton, breaking it only by three rounds of the vessel made precisely on the hours. After we grew to knew each other he would patrol the deck only at intervals, spending most of his watch seated on the cabin-deck at the break, on the rail or on the booby-hatch, according to the position of my chair. He mostly began.

"Have you ever read?" Or,

"Did you ever read?"

Sometimes I had read the book, oftener I had not. In either case I was fascinated by his sane, cool judgment, equally trenchant and subtle, and by the even flow of his well-chosen words.

Our voyage neared its end sooner than I had anticipated. The south-east trades had been almost head winds for us and we had tacked through them close-hauled, a long leg on the port tack and a short leg on the starboard. Then the proximity of the land blurred the unalterable perpetuity of the trade winds and on a Sunday morning the wind came fair. It was my first experience of running before the wind and it intoxicated me with elation. We were out of sight of land, even of its loom, yet no longer in blue water, but over that enormous sixty-fathom shelf which juts out more than a hundred miles into the Atlantic between Bahia and Rio de Janiero, or to be more precise, between Cannavieiras and Itapemirim. The day was bright and the sky sufficiently diversified with clouds to vary pleasingly its insistent blue, the sea a pale, golden green all torn by racing white-caps and dappled with the scurrying shadows of the clouds. The bark leapt joyously, the combers overtaking her charged in smothers of foam past each counter, the delight of merely living in such a glorious day infected even the crew.

I had my chair amidships by the break of the deck, just abaft the booby-hatch. There I was reading the Odyssey. The mate came and sat down by me on the booby-hatch.

"What are you reading?" he asked as usual.

"About the Sirens," I answered.

The strangest alteration came over his expression.

"Did you ever notice," he asked, "how little Homer really tells about them?"

"I was meditating on just that," I replied. "He tells only that there were two of them and that they sang. I was wondering where the popular notions of their appearance came from."

"What is your idea of the popular notions of their appearance?" he demanded.

"I have a very vague idea," I confessed.

"They are generally supposed to have had bird's feet. It seems to me I have seen figures of them as so depicted on Greek tombs and coins. And there is Boecklin's picture."

"Boecklin?" he ruminated. "The Munich man? The morbid man?"

"If you choose to call him so?" I assented. "I shouldn't call him morbid."

"His ugly idea is a mere personal conception," he said.

"I grant you that," I agreed, "as far as the age and the ugliness go. But the birds' feet of some kind are in the general conception."

"The general conception is wrong," he asserted, with something more like an approach to heat than anything I had seen in him.

"You seem to feel very sure," I replied.

"I do not feel," he answered, "I know."

"How do you know?" I inquired.

"I have seen them," he asserted.

"Seen them?" I puzzled.

"Yes, seen them," he asseverated. "Seen the twain Sirens under the golden sun, under the silver moon, under the countless stars; watched them singing as they are singing now!"

"What?" I exclaimed.

My face must have painted my amazement, my tone must have betrayed my startled bewilderment.

His face went scarlet and then pale. He sprang up and strode off to the weather rail. There he stood for a long time. Presently he wheeled, crossed the deck, the booby-hatch between us, and plunged down the cabin companion-way without looking at me.

He did not once meet my eye during the remaining days of the voyage, let alone approach me. He was again the impassive, inscrutable figure I had first seen him on the wharf at Baltimore.

We drew near Rio harbor, late of a perfect tropic September day, just too late to enter before sunset. In the brief tropic dusk we anchored under the black beetling shoulder of Itaipu inside the little islands of Mai and Pai. There we lay wobbling at anchor, there I watched the cloudless sky fill with the infinite multitudes of tropic stars, and gazed at the lights of the city, plainly visible through the harbor mouth between Morro de Sao Joao and the Sugar Loaf, twinkling brighter than the stars, not three miles away.

It must have been somewhere toward midnight when he approached me. My chair was by the rail on which he half sat, leaning down to me. So placed he began such a monologue as I had often heard from him, a monologue I could neither question nor modify, which I must listen to entire or break off completely.

"You were astonished," he said, "when I told you I had seen the Sirens, but I have. It was about six years ago, in 1879. I was in New York and I had my usual difficulty getting a ship on account of my deafness. My boarding-master tried a Captain George Andrews of the Joyous Castle. Andrews looked me over and said he liked me. Then he talked to me alone.

"'We are bound on an adventure,' he said, 'and I want a man who will obey orders and keep his mouth shut.'

"I told him I was his man for whatever risk. With a light mixed cargo, hardly more than half a cargo, hardly more than ballast, we cleared for Guam and a market. I was second mate. The first mate was a big Swede named Gustave Obrink. The very first meal I ever sat down to with him he made an impression on me as one of the greediest men I had ever seen. He not only ate enormously, but he seemed more than half unsatisfied after he had stuffed himself with an amazing quantity of food. He seemed to possess an unbluntable zest in the act of swallowing, an ever fresh gusto for any and every food flavor. I never saw a man relish his food so. He was an equally inordinate drinker, the quantity of coffee he could swill at one meal was amazing. Between meals he was always thirsty and drank incredible quantities of water. He was forever going to the butt by the galley door and drinking from it. And he would smack his lips over it and enjoy it as a connoisseur would a rare wine.

"When we came to choose watches Captain Andrews told us to choose a bo'sun for each watch. Obrink wanted to know why.

"The captain told him it was none of his business to ask questions. The Swede assented and backed down. We chose each an Irishman. Obrink, a tall, loose-jointed man named Pat Ryan and I, a compact stocky fellow named Mike Leary. Next day the captain had the boatswains shift their dunnage and bunk and mess aft. They were nearly as great gluttons as Obrink. They fed like animals and the subject of food and drink was the backbone of their conversation.

"The crew were hearty eaters as well and Captain Andrews catered to their likings. The Joyous Castle was amazingly well found, the cabin fare very abundant and varied, the forecastle food plenty and good.

"Soon after Captain Andrews was sure that the crew had entirely sobered up from their shore-drinking he called them aft one noon and announced that the steward was to serve grog daily until further notice. Naturally they cheered. After that we had a good, cheap wine daily in the cabin. When Captain Andrews had made up his mind that both mates and both boatswains were sober men he had a bottle of whisky placed on the rack over the table and kept filled. It was a curiosity to watch Obrink, Ryan and Leary patronize that bottle. Not one of the three but was cautious, not one of the three but could have drunk three times as much as he did. But the way they savored every drop they took, the affectionate satisfaction they exhibited over each nip, their eager anticipation of the next made a spectacle.

"Captain Andrews kept good discipline, we crossed the line and rounded the cape of Good Hope without any event.

"When we were off Madagascar, Obrink, going below to get his sextant, missed it from its place. The ship was searched and Captain Andrews held an inquisition. But the sextant was never found, nor any light thrown on how it had disappeared. After that the captain alone took the observations.

"Then began a series of erratic changes of our course. We kept on dodging about for six weeks, until the crew talked of nothing else and openly said the captain was trying to lose us; certainly not one of us except the captain could have designated our position. We knew we were south of the line, not ten degrees south of it, and between 50 and no east longitude, but within those limits we might be almost anywhere.

"We had had nothing that could be called a storm since we left New York. When a storm struck us it was a storm indeed. When it blew over it left us making water fast. After a day and a night at the pumps, we took to our boats. Captain Andrews had the cook and the cabin boy in his boat, gave each boatswain a dory and two men, and directed us to steer north by east. When Obrink and I asked for our latitude and longitude he said that was his business. He had had the boats provisioned while we pumped and they were well supplied. We left the ship under a clear sky, the wind light after the storm, the ground-swell running heavy and slow. We lowered near sunset.

"Next morning the Captain's boat had vanished, and there we were, two whale boats, two dories, twenty men in all and no idea of our position.

"The third day we sighted land. It was a low atoll, not much more than a mile across, nearly circular as far as we could make out, with the usual cocoa palms all along its ring, the surf breaking on interrupted reefs off shore, and, as we drew nearer, a channel into the lagoon facing us; as we threaded it we saw about the center of the lagoon a steep, narrow, pinkish crag, maybe fifty feet high, with a bit of flat island showing behind it. Otherwise the lagoon was unbroken. We made a landing on the atoll near the channel where we had entered, found good water, coconuts in abundance and hogs running wild all about, but no traces of human beings. I shot a hog and the men roasted it at once. As they ate they talked of nothing but the short rations they had had in the boats. They were all docile enough and good natured, but I believe every man of them said a dozen times how much he missed his grog and, Obrink, who had kept himself and his boat-load well in hand, said a score of times how much he would like to serve out grog, but must take care of his small supply. They talked a great deal of their hunger in the boats and of their relish for the pork; they ate an astonishing number of coconuts. It seemed to me that they were as greedy a set of men as could be met with.

"We cut down five palm-trees, and on supports made of the others set one horizontally as a ridge pole. Over this we stretched the sails of the whale-boats. So we camped on the sand-beach of the lagoon. I slept utterly. But when I waked I understood the men one and all to complain of light and broken sleep, of dreams, of dreaming they heard a queer noise like music, of seeming to continue to hear it after they woke. They breakfasted on another hog and on more coconuts.

"Then Obrink told me to take charge of the camp. I agreed. He had everything removed from his whale-boat and into it piled all the men, except a little Frenchman who went by no name save 'Frenchy,' a New Englander named Peddicord, a short red-headed Irishman named Mullen, Ryan, my boatswain and myself. Those of my watch who wanted to go I let go. They rowed off, across the lagoon toward the pink crag.

"After Obrink and the men were gone I meant to take stock of our stores. I sent Ryan with Frenchy around the atoll in one direction and Peddicord, who had sense for a foremast hand, with Mullen in the other direction. I then went over the stores. Fairly promising for twenty men they were, even a random boat-voyage in the Indian Ocean. With unlimited coconuts and abundant hogs they were a handsome provision, and need only be safeguarded from the omnipresent rats.

"Very shortly my four men returned, the two parties nearly at the same time. It was nearly noon, and no sign of Obrink or the boat. I had followed the whale-boat with my glass till it rounded the pink crag, a short half mile away, and had disappeared. Ryan asked my permission to take one dory and go join the rest on the crag. I readily agreed, for I had not yet cached the spirits. They rowed off as the others had.

"I made use of their welcome absence to conceal the liquor in four different places, carefully writing, in my note-book, the marks by which I was to find the caches again. I did the like with most of the ammunition. I had no idea of trying to get the upper hand of Obrink. I meant to tell him of my proceedings and expected him to approve.

"I expected the men back about two hours before sunset. No sign of them appeared. No sign of them near sunset, nor at sunset. Of course I had waited inactive till it was too late for me to venture alone on the unknown lagoon at night, and there would have been no sense in one man going to look for nineteen anyhow. Moreover I must protect our stores from hogs and rats. I turned over in my mind a thousand conjectures and slept little.

"Next morning I slung what I could of our stores from our jury-ridge-pole, out of the reach of hogs and rats, made sure that the remaining whale-boat would not get adrift, prepared the remaining dory with coconuts, biscuits, a keg of water, liquor, some miscellaneous stores, medicine, ammunition, repeating rifle, my glass and my compass. I carried two revolvers. I knew by this time something was wrong and I rowed warily across the placid lagoon toward the pink crag.

"As I approached it I could not but remark the peacefulness and beauty of my surroundings. The sky was deep tropic blue, the sun not an hour high, the wind a mild breeze, hardly more than rippling the lagoon, my horizon was all the tops of palms on the atoll except the one glimpse of white surf on the reef beyond the channel where we had entered.

"I rowed slowly, for the dory was heavy, and kept looking over my shoulder.

"The crag rose sheer out of deep water. It might have been granite, but I could not tell what sort of stone it was. It was very pink and nothing grew on it, not anything whatever. It was just sheer naked rock. As I rounded it I could see the flattish island beyond. There was not a tree on it and I could see nothing but the even beach of it rising some six or eight feet above high water mark. Nothing was visible beyond the crest of the beach. I knew our men had meant to land on it and I stopped and considered. Then I rowed round the base of the crag. Facing the flat islet was a sort of a shelf of the pink rock, half submerged, half out of the water, sloping very gently and just the place to make a landing. I rowed the dory carefully till its bottom grated on the flat top of this shelf, the bow in say a foot of water, the stern over water may be sixty fathom deep, for I could see no bottom to its limpid blue. I stepped out and drew the dory well up on the shelf. Then I essayed to climb the crag. I succeeded at once, but it was none too easy and I had no leisure to look behind me till I reached the top. Once on the fairly flat top, which might have been thirty feet across, I turned and looked over the islet.

"Then I sat down heavily and took out my flask. I took a big drink, shut my eyes, said a prayer, I think, and looked again. I saw just what I had seen before.

"There was about a ship's-length of water between the crag and the islet, which might have been four ships-lengths across and was nearly circular. All round it was a white beach of clean coral-sand sloping evenly and rising perhaps ten feet at most above high-water mark. The rest of the island was a meadow, nearly level but cupping ever so little from the crest of the beach. It was covered with short, soft-looking grass, of a bright pale green, a green like that of an English lawn in Spring. In the center of the island and of the meadow was an oval slab of pinkish stone, the same stone, apparently, as made up the crag on which I sat. On it were two shapes of living creatures, but shapes which I rubbed my eyes to look at. Midway between the slab and the crest of the beach a long windrow heap of something white swept in a circle round the slab, maybe ten fathom from it. I did not surely make out what the windrow was composed of until I took my glasses to it.

"But it needed no glass to see our men, all nineteen of them, all sitting, some just inside the white windrow, some just outside of it, some on it or in it. Their faces were turned to the slab.

"I took my glass out of my pocket, trembling so I could hardly adjust it. With it I saw clearly, the windrow as I had guessed, the shapes on the slab as I had seemed to see them with my unaided eyes.

"The windrow was all of human bones. I could see them clearly through the glass.

"The two creatures on the slab were shaped like full-bodied young women. Except their faces nothing of their flesh was visible. They were clad in something close-fitting, and pearly gray, which clung to every part of them, and revealed every curve of their forms; as it were a tight-fitting envelopment of fine mole-skin or chinchilla. But it shimmered in the sunlight more like eider-down.

"And their hair! I rubbed my eyes. I took out my handkerchief and rubbed the lenses of my glasses. I looked again. I saw as before. Their hair was abundant, and fell in curly waves to their hips. But it seemed a deep dark blue, or a dull intense shot-green or both at once or both together. I could not see it any other way.

"And their faces!

"Their faces were those of white women, of European women, of young handsome gentlewomen.

"One of them lay on the slab half on her side, her knees a little drawn up, her head on one bent arm, her face toward me, as if asleep. The other sat, supporting herself by one straight arm. Her mouth was open, her lips moved, her face was the face of a woman singing. I dared not look any more. It was so real and so incredible.

"I scanned our men through my glass. I could see their shoulders heave as they breathed, otherwise not one moved a muscle, while I looked him.

"I shut my glass and put it in my pocket. I shouted. Not a man turned. I fixed my gaze so as to observe the whole group at once. I shouted again. Not a man moved. I took my revolver from its holster and fired in the air. Not a man turned.

"Then I started to clamber down the crag. I had to turn my back on the islet, regard the far horizon, fix my gaze on the camp, discernible by the white patch, where the white sails were stretched over the palm trunk and try to realize the reality of things before I could gather myself together to climb down.

"I made it, but I nearly lost my hold a dozen times.

"I pushed off the dory, rowed to the islet, and beached the dory between the other and the whale-boat. Both were half adrift and I hauled them up as well as I could.

"Then I went up the beach. When I came to its crest and saw the backs of our men I shouted again. Not a man turned his head. I approached them, their faces were set immovably towards the rock and the two appearances on it.

"Peddicord was nearest to me, the windrow of bones in front of him was not wide nor high. He stared across it. I caught him by the shoulders and shook him, then he did turn his head and look up at me, just a glance, the glance of a peevish, protesting child disturbed at some absorbing play, an unintelligent vacuous glance, unrecognizing and uncomprehending.

"The glance startled me enough, for Peddicord had been a hard-headed, sensible Yankee. But the change in his face, since yesterday, startled me more. Of a sudden I realized that Peddicord, Ryan, Mullen and Frenchy had been without food or water since I last saw them, that they had been just where I found them since soon after they left me, had been exposed the day before to a tropical sun for some six hours, had sat all night also without moving, or sleeping. At the same instant I realized that the rest had been in the same state for some hours longer, some hours of a burning, morning tropical sun. The realization of it lost my head completely. I ran from man to man, I yelled, I pulled them, I struck them.

"Not one struck back, or answered, or looked at me twice. Each shook me off impatiently and, relapsed into his intent posture, even Obrink.

"Obrink, it is true, partially opened his mouth, as if to speak.

"I saw his tongue!

"I ran to the boat, took a handful of ship-biscuit and a pan of water, with these I returned to the men.

"Not one would notice the biscuit, not one showed any interest in the water, not one looked at it as if he saw it when I held it before his face, not one tried to drink, not one would drink when I tried to force it on him.

"I emptied my flask into the water, with that I went from man to man. Not even the smell of the whisky roused them. Each pushed the pan from before his face, each resisted me, each shoved me away.

"I went back to the boat, filled a tin cup with raw whisky and went the round with that. Not one would regard it, much less swallow it.

"Then I myself turned to the slab of stone.

"There sat the sirens. Well I recognized now what they were. Both were awake now and both singing. What I had seen through the glass was visible more clearly, more intelligibly. They were indeed shaped like young, healthy women; like well-matured Caucasian women. They were covered all over with close, soft plumage, like the breast of a dove, colored like the breast of a dove, a pale, delicate, iridescent, pinkish gray. As a woman's long hair might trail to her hips, there trailed from their heads a mass of long, dark strands. Imagine single strands of ostrich feathers, a yard long or more, curling spirally or at random, colored the deep, shot, blue-green of the eye of a peacock feather, or of a game-cock's shackles. That was what grew from their heads, as I seemed to see it.

"I stepped over the windrow of bones. Some were mere dust; some leached gray by sun, wind and rain; some white. Skulls were there, five or six I saw in as many yards of the windrow near me and more beyond. In some places the windrow was ten feet wide and three feet deep in the middle. It was made up of the skeletons of hundreds of thousands of victims.

"I took out my other revolver, spun the cylinder, and strode toward the slab.

"Forty feet from it I stopped. I was determined to abolish the superhuman monsters. I was resolute. I was not afraid. But I stopped. Again and again I strove to go nearer, I braced my resolutions. I tried to go nearer. I could not.

"Then I tried to go sideways. I was able to step. I made the circuit of the slab, some forty feet from it. Nearer I could not go. It was as if a glass wall were between me and the sirens.

"Standing at my distance, once I found I could go no nearer, I essayed to aim my revolver at them. My muscles, my nerves refused to obey me. I tried in various ways. I might have been paralyzed. I tried other movements, I was capable of any other movement. But aim at them I could not.

"I regarded them. Especially their faces, their wonderful faces.

"Their investiture of opalescent plumelets covered their throats. Between it and the deep, dark chevelure above, their faces showed ivory-smooth, delicately tinted. I could see their ears too, shell-like ears, entirely human in form, peeping from under the glossy shade of their miraculous tresses.

"They were as like each other as any twin sisters.

"Their faces were oval, their features small, clean-cut, regular and shapely, their foreheads were wide and low, their brows were separate, arched, penciled and definite, not of hair, but of tiny feathers, of gold-shot, black, blue-green, like the color of their ringlets, but far darker. I took out my binoculars and conned their brows. Their eyes were dark blue-gray, bright and young, their noses were small and straight, low between the eyes, neither wide nor narrow, and with molded nostrils, rolled and fine. Their upper lips were short, both lips crimson red and curved about their small mouths, their teeth were very white, their chins round and babyish. They were beautiful and the act of singing did not mar their beauty. Their mouths did not strain open, but their lips parted easily into an opening. Their throats seemed to ripple like the throat of a trilling canary-bird. They sang with zest and the zest made them all the more beautiful. But it was not so much their beauty that impressed me, it was the nobility of their faces.

"Some years before I had been an officer on the private steam-yacht of a very wealthy nobleman. He was of a family fanatically devoted to the church of Rome and all its interests. Some Austrian nuns, of an order made up exclusively of noblewomen, were about to go to Rome for an audience with the Pope. My employer placed his yacht at their disposal and we took them on at Trieste. They several times sat on deck during the voyage and the return. I watched them as much as I could, for I never had seen such human faces, and I had seen many sorts. Their faces seemed to tell of a long lineage of men all brave and honorable, women gentle and pure. There was not a trace on their faces of any sort of evil in themselves or in anything that had ever really influenced them. They were really saintly faces, the faces of ideal nuns.

"Well, the sirens' faces were like that, only more ineffably perfect. There was no guile or cruelty in them, no delight in the exercise of their power, no consciousness of it, no consciousness of my proximity, or of the spell-bound men, or of the uncountable skeletons of their myriad victims. Their faces expressed but one emotion: utter absorption in the ecstasy of singing, the infinite preoccupation of artists in their art.

"I walked all round them, gazing now with all my eyes, now through my short-focused glass. Their coat of feathers was as if very short and close like seal-skin fur and covered them entirely from the throat down, to the ends of their fingers and the soles of their feet. They did not move except to sit up to sing or lie down to sleep. Sometimes both sang together, sometimes alternately, but if one slept the other sang on and on without ceasing.

"I of course could not hear their music, but the mere sight of them fascinated me so that I forgot my weariness from anxiety and loss of sleep, forgot the vertical sun, forgot food and drink, forgot my shipmates, forgot everything.

"But as I could not hear this state was transitory. I began to look elsewhere than at the sirens. My gaze turned again upon the men. Again I made futile efforts to reach the sirens, to shoot at them, to aim at them. I could not.

"I returned to my dory and drank a great deal of water. I ate a ship-biscuit or two. I then made the round of the men, and tried on each food, water and spirits. They were oblivious to everything except the longing to listen, to listen, to listen.

"I walked round the windrow of bones. With the skulls and collapsing rib-arches I found leather boots, several leather belts, case-knives, kreeses, guns of various patterns, pistols, watches, gold and jeweled finger rings and coins, many coins, copper, silver and gold. The grass was short, not three inches deep and the earth under it smooth as a rolled lawn.

"The bones were of various ages, but all old, except two skeletons, entire, side by side, just beyond the windrow at the portion opposite where the men sat. There was long fine golden hair on one skull. Women too!

"I went back to the dory, rowed to the camp, shot a hog, I roasted it, wrapped the steaming meat in fresh leaves and rowed back to the islet. It was not far from sunset.

"Not a man heeded the savory meat, still warm. They just sat and gazed and listened.

"I was free of the spell. I could do them no good by staying. I rowed back to camp before sunset and slept, yes I slept all night long.

"The sun woke me. I shot and cooked another hog, took every bit of rope or marline I could find and rowed back to the islet.

"You are to understand that the men had by then been more than forty hours, all of them, without moving or swallowing anything. If I was to save any it must be done quickly.

"I found them as they had been, but with an appalling change in themselves. The day before they had been uncannily unaware of their sufferings, to-day they were hideously conscious of them.

"Once I had a pet terrier, a neat, trim, intelligent, little beast. He ran under a moving train and had both his hind legs cut off. He dragged himself to me, and the appealing gaze of his eyes expressed at once his inability to comprehend what had happened to him, his bewilderment at pain, the first really excruciating pain he had ever known in all his little life, and his dumb wonder that I did not help him, that it could be possible he could be with me and his trouble continue.

"Once I had the misfortune to see a lovely child, a beautiful little girl, not six years old, frightfully burned. Her look haunted me with the like incomprehension of what had befallen her, the like incredulity at the violence of her suffering, the like amazement at our failure to relieve her.

"Well, out of the staring, blood-shot eyes of those bewitched men I saw the same look of helpless wonderment and mute appeal.

"Strange, but I never thought of knocking them senseless. I had an idea of tying them one by one, carrying or dragging them to the dory and ferrying my captives to camp.

"I began on Frenchy, he was nearest the boat and smallest.

"He fought like a demon. After all that sleeplessness and fasting he was stronger than I. Our tussle wore me out, but moved him not at all.

"I tried them with the warm juicy, savory pork. They paid no heed to it and pushed me away. I tried them with biscuit, water and liquor. Not one heeded. I tried Obrink particularly. Again he opened his lips. His tongue was black, hard, and swelled till it filled his mouth.

"Then I lost count of time, of what I did, of what happened. I do not know whether it was on that day or the next that the first man died. He was Jack Register, a New York wharf-rat. The next died a few hours later, a Philadelphia seaman he was, named Tom Smith.

"They putrefied with a rapidity surpassing anything I ever saw, even in a horse dropped dead of over-driving.

"The rest sat there by the carrion of their comrades, rocking with weakness, crazed by sleeplessness, racked by tortures inexpressible, the gray of death deepening on their faces, listening, listening, listening.

"As I said, I had lost consciousness of time. I do not know how many days Obrink lived, and he was the last to die. I do not know how long it was after his death before I came to myself.

"I made one last effort to put an end to the enchantresses. The same spell possessed me. I could not aim, much less pull trigger; I could not approach nearer than before.

"When I was myself I made haste to leave the accursed isle. I made ready the second whale-boat with all the best stores she could carry and spare sails. I stepped the mast and steered across the lagoon, for the wind was southerly and there was a wider channel at the north of the atoll.

"As I passed the islet, I could see nothing but the white sand beach that ringed it. For all my horror I could not resist landing once more for one last look.

"Under the afternoon sun I saw the green meadow, the white curve of ones, the rotting corpses, the pink slab, the feathered sirens, their sweet serene faces uplifted, singing on in a rapt trance.

"I took but one look. I fled. The whale-boat passed the outlet of the lagoon. North by east I steered.

"Parts of the Indian Ocean are almost free of storms. The atoll was apparently in one of those parts. I soon passed out of it. Three storms blew me about, I lost my dead-reckoning, I lost count of the days. Between the storms I lashed the tiller amidships, double-reefed the sail and slept as I needed sleep. Through the storms I bailed furiously, the whale-boat riding at a sea-anchor of oars and sails. I had been at sea alone for all of twenty-one days when I was rescued, not three hundred miles from Ceylon, by a tramp steamer out of Colombo bound for Adelaide."

Here he broke off, stood up and for the rest of the watch maintained his sentry-go by the break of the poop.

NEXT DAY we towed into the harbor of Rio de Janeiro, then still the capital of an Empire, and mildly enthusiastic for Dom Pedro. I hastened to go ashore. When my boat was ready the deaf mate was forward, superintending the sealing of the hatches.

After some days of discomfort at the Hôtel des Étrangers and of worse at Young's Hotel I found a harborage with five jolly bachelors housekeeping in a delightful villa up on Rua dos Jonquillos on Santa Theresa. The Nipsic was in the harbor and I thought I knew a lieutenant on her and went off one day to visit her. After my visit my boatman landed me at the Red Steps. As I trod up the steps a man came down. He was English all over, irreproachably shod, trousered, coated, gloved, hatted and monocled. Behind him two porters carried big, new portmanteaux. I recognized the man whom I had known as John Wilson of Liverpool, second mate of the Medorus, the man who had seen the Sirens.

Not only did I recognize him, but he recognized me. He gave me no far off British stare. His eyes lit, even the monocled eye. He held out his hand.

"I am going home," he said, nodding toward a steamer at anchor, "I am glad we met. I enjoyed our talks. Perhaps we may meet again."

He shook hands without any more words. I stood at the top of the steps and watched his boat put off, watched it as it receded. As I watched a bit of paper on a lower step caught my eye. I went down and picked it up. It was an empty envelope, with an English stamp and postmark, addressed:

Geoffrey Cecil, Esq.,

c.o. Swanwick & Co.,

54 Rua de Alfandega,

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

I looked after the distant boat, I could barely make him out as he sat in the stern. I never saw him again.

NATURALLY I asked every Englishman I ever met if he had ever

heard of a deaf man named Geoffrey Cecil. For more than ten years

I elicited no response. Then at lunch, in the Hotel Victoria at

Interlaken, I happened to be seated opposite a stout, elderly

Briton. He perceived that I was an American and became affable

and agreeable. I never saw him after that lunch and never learned

his name. But through our brief meal together we conversed

freely.

At a suitable opportunity I put my usual query.

"Geoffrey Cecil?" he said. "Deaf Geoffrey Cecil? Of course I know of him. Knew him too. He was or is Earl of Aldersmere."

"Was or is?" I queried.

"It was this way," my interlocutor explained. "The ninth Earl of Aldersmere had three sons. All predeceased him and each left one son. Geoffrey was the heir. He had wanted to go into the Navy, but his deafness cut him off from that. When he quarreled with his father he naturally ran away to sea. Track of him was lost. He was supposed dead. That was years before his father's death. When his father died nothing had been heard of him for ten years. But when his grandfather died and his cousin Roger supposed himself Earl, some firm of solicitors interposed, claiming that Geoffrey was alive. That was in 1885. It was a full six months before Geoffrey turned up. Roger was no end disappointed. Geoffrey paid no attention to anything but buying or chartering a steam-yacht. She sailed as soon as possible, passed the canal, touched at Aden, and has never been heard of since. That was nine years ago."

"Is Roger Cecil alive?" I asked.

"Very much alive," affirmed my informant.

"You may tell him from me," I declared, "that he is now the Eleventh Earl of Aldersmere."

WHEN through the fire nothing remained discernible, when peering and gazing they saw only flame within flame, two of her women gently drew Anna away from the pyre. She let herself be conducted across the courtyard and up the easy stone stair to the first gallery. There, hanging over the polished marble railing of the balustrade, her head leaned against one of the columns, Anna watched the burning pyre. It blazed on, even larger and fiercer, for a string of porters and workmen carrying logs or faggots, filed into the court. Each threw his burden upon the pyre and passed out by another door. Others followed in like manner, and, after a time, the same men returned again with fresh burdens.

From her place by the pillar of the gallery Anna refused to stir.

Several of the women carried in a broad, cushioned couch, placed it silently behind their lady and gently induced her to recline upon it. So reclining she leaned her bosom against the balustrade, her arms upon its rail, her head upon her arms. There she fell asleep.

All night, the slaves in single file carried fuel to keep up the blaze. When the first dawn-light appeared in the sky overhead and the pigeons began to coo upon the red-tiled roofs of the palace, Anna awakened and gave a soft-voiced order. The fuel-carriers ceased to file into the court, the last of them went their way and the pyre was left to burn out of itself.

Watching its fury slacken and its blaze abate Anna, partly from innate docility, partly from dazed indifference, passively permitted her maids to bathe her face and hands, to bind up her hair, somewhat to arrange her dress. She even compliantly swallowed some mouthfuls of the bread moistened with hot spiced wine which they urged upon her. She allowed them to unclasp her nerveless fingers from the tear-soaked square of linen they clutched, to place in them another.

Tactfully they withdrew some little distance and left her absorbed in her grief, oblivious of all other things, droopingly half -supported against the balustrade and pillar, watching the pyre sink into a bed of glowing coals. She stared down at it, weeping softly, now and then sobbing, and once and again dabbing at her eyes with the square of linen she held crumpled in her hand. The women slaves, huddled out of sight under the lower arcade, kept up a monotonous shrill wailing, a weird, droning noise which had become less and less insistent as the hours passed. Through it Anna was aware of a different sound.

She heard the clank and tinkle of jangling armor and glanced across the court. Between two pillars of the lower colonnade in front of the main central doorway stood Iarbas. The scarlet plume of his helmet-crest nodded still and waved as his crimson cloak fluttered and undulated behind him with the impetus of his checked haste; the dawn-light and the fire-light glittered and gleamed on the brow-piece of his helmet, on the gilded links of his chain corselet, on the burnished scales of his broad kilt-straps, and shone on the great round shield and the broad polished points of the twin spears his armor-bearer carried behind him. His eyes were bright in his big swarthy face, and roved about the court gazing at the huddled crowd of servitors and menials under the side-colonnades, at the dying glow of the sinking pyre, at Anna and her attendants above. He waved his hand backward with a single imperious gesture and strode across the court. Anna heard his tread on the tesselated floor of the gallery and looked around at him, half sitting up, but still limply leaning upon the balustrade, her head against the pillar. She said nothing.

Weeping did not disfigure Anna. Her pale gold hair rippled ever so little over her temples, her pale blue eyes gazed from unreddened lids, her pale pinkish cheeks were not streaky with her hours of tears, her mild oval face was pretty as it had been throughout her past, whether she had been anxious and worried or happy and gay. Iarbas looked her over from the grass-green sandal-straps across the small arched instep showing under the embroidered hem of her sea-green gown to the jade brooch at her shoulder and the apple-green ribbon which confined her hair. He found himself astonished at her comeliness, he had never noted her looks before.

She gazed at him steadily, mute.

"I am a day too late," he said.

She turned from him, buried her face upon her crossed arms, and burst into a passion of sobs.