RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

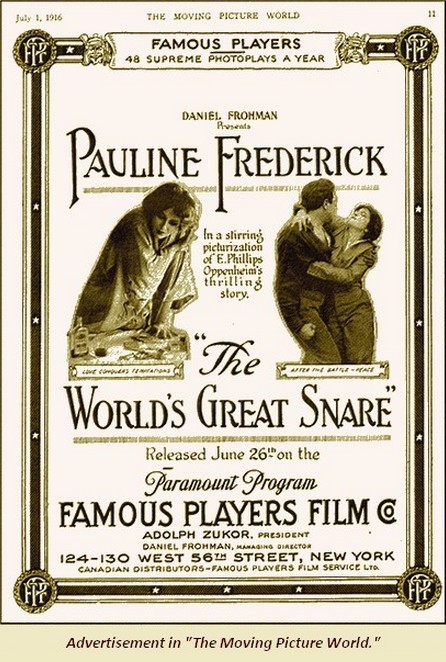

"The World's Great Snare," Ward, Lock & Co., 1935 Edition

"The World's Great Snare," Little, Brown & Co., Boston, 1913

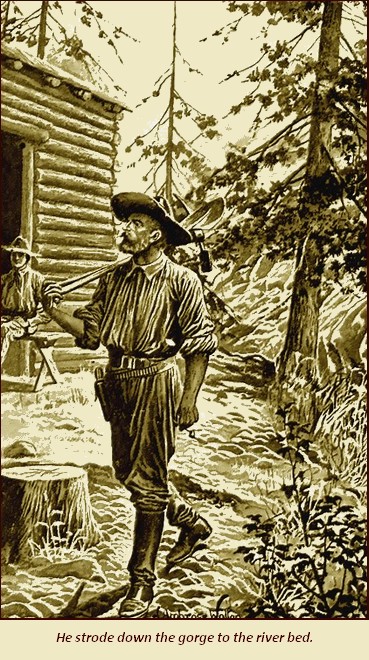

Frontispiece

"At last!" muttered Mr. James Hamilton, opening his eyes and sitting upright on the floor. "Get up, you chaps! D'ye hear? Get up!"

No one stirred. As a matter of fact, neither of the other two men was awake. With a final yawn the speaker stretched himself out and staggered to his feet. Then he threw himself upon a rude wooden bench, picked up the stump of a corn-cob pipe which lay upon the ground, and smoked, with his elbows resting upon the empty window-frame, and his head stretched as far as possible outside. The dull stolidity of his features was quickened for the moment into the semblance of eagerness. He was waiting to inhale the faint quivering breeze which was stealing down from the hills.

"At last!" he growled, with his eyes, dim and bloodshot, turned towards the western sky. "What a hell of a day! There she goes, and be d—d to her!"

The rim of a red, burning sun had touched at last the highest peak of a low range of pine-topped hills crawling around the base of the Sierras. All day long, the heat in the valley and across that level stretch of rocky, broken country lying eastwards, had scorched the earth, dried up the watercourses, and very nearly turned the brains of those few dwellers around the banks of the Blue River. Work had been given up as a thing impossible. Down below where, around the bed of the old river, a score or so of gold claims had been staked out by a little band of eager workers, reigned a deep, absolute stillness. Pickaxes, washers, pans, and all sorts of mining tools were lying about unused. Not a man had dared to breathe the burning heat and stifling air of the valley. Apart, they might have been borne for a brief while, at any late; together, they meant fever, deadly and virulent.

After a while, Mr. James Hamilton withdrew his head from the window-frame, and cast a grim look into the interior of the shanty. Save for its occupants, it did not afford much scope for investigation, nor was there anything in its appointments which could have offended the instincts of the most rigid ascetic. On a table constructed of a couple of broad planks from which the underneath bark had not been stripped, supported upon a barrel at either end, were scattered a dirty pack of cards, two tin mugs turned upside down, and a black bottle rolling on its side. The walls were perfectly bare, and a strong woody odour, and the tricklings of pine sap upon the rafters, showed that the shanty had only recently been put together. The whole of the floor seemed to be taken up by the two men who lay there fast asleep.

It was upon the face of the one nearest to him that Mr. James Hamilton's attention seemed fixed. With his hands on his knees, and his pipe between his teeth, he leaned forward, watching him with a steady, expressionless scrutiny. If the sleeping man had suddenly awakened, there was nothing in the look to terrify or even surprise him. It was simply the steady, critical survey of a man who desires to impress certain features and lineaments in his memory, or compare them with some previous association.

They were all three big men, with brawny limbs and muscles hardened and distended by physical labour, but the man who slept so soundly was almost a giant. His head, massive and tawny-bearded, was propped up against the opposite wall. One huge arm, naked to the shoulder, was passed underneath it, and the other, stretched out perfectly straight, reached the doorway. One of his feet, bare and brown, rested upon an overturned bucket; the leg, extended at full length, seemed in the tiny cabin like the limb of a giant. A red flannel shirt, unbuttoned at the throat, revealed a mighty chest, curiously white. His trousers, of coarse linen, were rolled up to the knees, and although stained and discoloured, showed traces of constant efforts at cleaning.

Mr. James Hamilton, whose eyes had been noting this amongst many other things, suffered for the first time a shade to pass across his face. He gave vent to his feelings in an expressive grunt, and spat upon the floor.

After that first futile summons, he seemed in no hurry to awaken his comrades. Withdrawing his eyes at last from the man who lay stretched at his feet, he carefully stepped over his body, and lounged to the doorway. The frail structure creaked with his weight as he leaned against the side, for Mr. James Hamilton himself was a fourteen-stone man, but he made himself comfortable there and folded his arms, smoking steadily, and watching the dull red ball of sun sink behind the hills. Unconsciously he contributed one more, and a necessary figure, to the dramatic completeness of the scene.

Down from the hills stole the softly-descending darkness. There was none of the lingering twilight of an English summer. Swift shadows moved ghostlike across their bare brown sides, and hung about the valley, and the colour stole into a white moon hung in a deep blue sky. A breeze, long desired and grateful, swept through the army of pines which crowned the sheer hill behind the cabin, hanging on to its ledges and crevices, and growing out in places almost at right angles to the precipice below. Mr. James Hamilton took off his apology for a hat, and pushed his hair back from his head, to taste as much of its sweetness as he could. He even glanced over his shoulder into the cabin, and seemed to contemplate another attempt at arousing his companions. But, although he went so far as to remove his pipe from his teeth, he did not at once speak to them.

"I reckon this is the darnedest, loneliest, saddest hole I ever came across!" he muttered to himself, gazing away from the valley and the shadow-crowned hills to where a great rolling expanse of broken country surged away to the eastern horizon. Mr. Hamilton's artistic education had been neglected, and he saw no beauty in the fantastic panorama of shadowland, the lone clumps of alder-trees and bushes the very leaves of which seemed like elegant tracing against the deep clear sky, and the faint blue haze mingling with the deeper twilight. His regretful thoughts at that moment were fixed upon a certain pine-board saloon a few hundred miles beyond that uncertain line where the rolling plain touched the sky, and the music of the quivering breeze amongst the pines fell upon dull, unappreciative cars. The fact undoubtedly was, that Mr. James Hamilton was sharing a similar sensation to that which a goodly proportion of his fellow-creatures, steeped to the finger-tips in Eastern civilization, encounter every day. He was bored! The absence of kindred spirits, the enforced temperance of hard work, and, as he expressed it, the cursed loneliness of the place, were becoming insufferable. It was possible, too, that he was a little homesick; for Mr. James Hamilton was not an American, and had not been heard to express any unbounded admiration for that country. The only thing, in fact, which had won his unqualified approval were the oaths, which he had mastered with wonderful facility, and by means of which he was able, as he remarked with constant satisfaction, to express himself as a gentleman.

Yet, although he was unaware of it, the loneliness was not quite so complete as he had imagined. Away across the broken plain, the figure of a human being was slowly limping and crawling along the rough track towards the valley; a human being in the direst and most pitiful of straits. As yet, all signs of the little settlement and the river were hidden from him. He was in a vast lonely stretch of barren country, with the great hills in front, and no sign of human life or habitation to break the deep serene silence. Every now and then a moan broke from the white parched lips, a low despairing moan of pain and deep physical exhaustion, and more than once in the short space of a hundred yards, he threw up his arms and sank down upon the ground. He was dressed in the roughest of cowboy's clothes stained with sun and water, and torn almost to rags by the bushes of the forests. His face was worn to a shadow, and black rims were under the deep-set eyes bright with the gleam of famine. The feet were bare and stained with blood, and the hands were cut and bruised. And with it all he seemed to have the look of one utterly unused to such privations. The shape of his limbs was slender, even delicate, and the face, notwithstanding its emaciation and deadly pallor, was curiously handsome. He carried no gun or stick, but a small bundle from which the butt-end of a revolver was sticking out, and as once more his feet gave way beneath him and he sank down, his fingers closed upon it convulsively.

He lay upon his back, and looked up at the stars which were beginning to steal into the sky. For a moment his mind began to wander. Trees and sky and space seemed to be mingling in one confused chaos. Then, setting his teeth and making a great effort, he arrested his fleeting consciousness. He raised his head a little and his lips moved.

"Oh, God! if I could crawl but just a mile—just a mile or two further! I must be near the Blue River now! Yonder are the mountains—that must be the valley! Oh, if only I had the strength!"

He raised himself a little more and looked around despairingly. The deep, majestic stillness of the great pine-clad hills and brooding forests, the solemn silence of night descending slowly upon the land, seemed to stir up a sudden half-frenzied anger in the traveller. Was he to die there in agony, almost within sight of his goal? To die before the yellow light faded from that great moon, and the slow-flushing morn paled the eastern skies? Even in his growing weakness, the cruelty of it and the deep, solemn indifference of all inanimate things in the face of his misery, came vividly home to him. With a curious mixture of blasphemy and devotion, he sat up and faintly cursed the distant moonlit hills, the perfumed breeze which fanned his burning forehead, and the far-off sound of a mountain torrent which mocked his dry throat and cracked lips. Then he pulled out his revolver.

"One shot more!" he gasped. "Shall I?"

He looked into the deep barrel, and held it to his forehead, pressing it there so tightly that when his fingers relaxed there was a livid red mark upon his temple. Then he laid it down by his side, and sitting up, sobbed out loud.

"Oh, God help me! God help me!" he moaned. "I daren't die! I'm afraid! Oh, for just a little more strength, only just a little! I must be nearly there!"

He raised himself slowly on to his knees, and leaned forward on his hands. Behind him lay the great desolate plain melting into the sky. In front were the mountains, the deep gorge, the pine-topped hills; and, at their base, though he could not see it, the little shanty where two men slept and one watched.

"I must be near there now!" he gasped. "Very near! One more effort now—one more—and if I fail—I will do it!"

He replaced the revolver in the little bundle, and pushed back the thick hair from his forehead, with a gesture of determination. Then moving, in pain and slowly, on hands and feet, he crept on with his face towards the hills, muttering softly to himself:

"I must not give up! I will—be brave! I will not faint! No! I will not, I will not! How brightly the moon shines through the dark trees, and what strange shadows lie across the plain! Down there must be the valley. Yes, yes; that is where they are. I have come so far—I will not give in! I shall find him. Yes, I shall find him! The ground seems unsteady! it is fancy, fancy! Just beyond those trees—that is where they will be. It is—very near. The breeze is fragrant with the perfume of the pines. It is—only a little further. I shall soon be there—very soon. Ah, what is that? How bright it is! Oh, God! do not mock me. It is a firefly, it must be—a firefly! I will not believe that it is a light. Oh, my head! How giddy I am! I must not give way. I will not! I will not! It is—ah!"

He sprang to his feet, and raised his hands to heaven. A sudden wild joy shook him.

"It is a light—a match!" he shrieked. "I am there!"

Mr. Hamilton's pipe had gone out, and the tobacco was in his host's possession. He turned round and kicked the body of the man nearest to him.

"Hullo!" he cried. "Are you chaps turned into logs? Get up!"

The man more directly addressed opened his eyes, gave a mighty yawn, and staggered to his feet. Then he thrust his head out of the door, and drew a long breath.

"Whew! This is good!" he exclaimed, opening his lungs and breathing in great gulps of the fragrant pine-scented breeze which was blowing softly across the gorge from the forests beyond. "Jim, you idiot, why didn't you wake me before?

"Not my business!" Mr. Hamilton growled. "Shouldn't have done it now, only I wanted a smoke. Hand over the baccy!"

His host produced a huge pouch from his pocket, filled his own pipe and handed it over. Mr. Hamilton, still lounging in the doorway, leisurely stuffed his corn-cob as full as he could, struck a match, and thereby, in all probability, saved the life of a fellow-creature.

Neither of the men heard the faint despairing cry of the stranger. After smoking for a few moments in silence, they were joined by the third occupant of the shanty. He was a tall, lank man, with grizzled hair, high cheekbones, and clear gray eyes. After his first uprising he stood for a brief while indulging in a succession of yawns. Then he felt for his pipe, snapped his fingers for the tobacco, and, leaning against the wall, smoked in silence.

"Say, pal, how's the liquor?" grunted Mr. Hamilton insinuatingly, a sudden gleam of interest illuminating his classical features. "It's a cussed dry climate!"

His host, who in the little community was generally called the Englishman, stretched out his hand and drew a bottle from a wooden box set on end, which appeared to do duty as a cupboard. He turned it upside down, and contemplated it thoughtfully, smoking all the time.

"Half a bottle," he announced. "All we've got, and no supplies for a week! Guess we'd better thirst!"

"That be d—d!" growled Mr. Hamilton. "This place is as slow as hell, anyhow. Let's share up, and have a game of poker. Chance to-morrow! I shall cut my throat if I don't have a drink!"

The Englishman balanced the bottle thoughtfully in the palm of his hand

"What do you say, Pete?" he asked, turning to the other man.

The gentleman addressed, Mr. Peter Morrison by name, scratched his head and glanced furtively at the sullen brow and red, bloodshot eyes of the man who lounged in the doorway. The sight seemed to decide him.

"I say let's drink! I saw Dan Cooper this morning, and he allowed there was plenty of stuff left in the store. We shan't have a much drier day than this, anyhow."

"D—d poor stuff that store whisky," muttered the Englishman. "Two against one takes it, though. Down you sit, you chaps! Share up the liquor. Here goes! Jim, deal the pictures!"

The men sat down without a word. In silence they drank and smoked, dealt and shuffled, lost and won. Loquacity was not a popular quality at Blue River diggings, and conversation was a thing almost unheard-of. Only, once Mr. Hamilton brought his fist down upon the frail table, and took his pipe from his mouth.

"You chaps, I'm off next week. Gold-diggin's a frost. D—d if I can stand it any longer. Say, are you coming, Bryan?"

The Englishman shook his head.

"Going to hold on a bit longer," he answered. "Shouldn't half mind it if it wasn't so blazing hot!"

"How about you, Pete?" Mr. Hamilton inquired, turning to the other man.

"I'm in with Bryan," was the quiet reply. "We're pards, you know. Ain't that so, Bryan?"

"Right for you, my man!" was the hearty answer. "Two pairs, aces up! Show your hand, Jim!"

Mr. Hamilton threw down his cards with a string of oaths which even surpassed his usual brilliancy.

"You fellows can stay and rot here," he muttered hoarsely. "Just you wait till the rains come, and see how you like it."

There was no further attempt at conversation. Every now and then Mr. Hamilton swore a deep oath as the cards went against him, which was not often. The Englishman and his partner won or lost without a murmur—the former with real carelessness, the latter with a studied and characteristic nonchalance. Mr. Hamilton was the only one who showed any real interest in the game, and his method of playing, which was a little peculiar, required all his attention.

Outside, the calm of evening deepened into the solemn stillness of night. The moon rose over the pine tops, and the mists floated away down the valley. The breeze dropped, and the trees in the forest were dumb. The three men played steadily on till midnight. Then the Englishman rose up and threw down his cards.

"Out you go, you chaps!" he said shortly. "I've had enough of this, and I'm going to turn in."

The two men rose: Mr. Hamilton grumbling, Morrison as silent as ever. Together they all walked out into the darkness.

"Good night, and be d—d to you!" muttered Mr.

Hamilton surlily as he scrambled down the hillside, holding on to the young fir-trees, and every now and then balancing himself with difficulty. "What the devil were you thinking of when you built your shanty up in the clouds?" he shouted back as at last he reached the bottom. "I'm bruised all over. I'll be shot if I come again."

The Englishman laughed out lustily, and thrust his hands into his pockets.

"Good night, Jim!" he shouted, his deep bass voice awakening strange echoes as it travelled across the rocky gorge. "Don't know what you want to swear at me for! You've drunk my whisky, and smoked my tobacco, and won my money, you surly beggar, you! Good night, Pete!" he added to his partner in a milder tone. "Be careful how you go, there! You've had as much liquor as you can carry, you have, you idiot!"

He walked a step or two further out, and watched both men gain their shanties. Then he turned round and stood for a moment or two gazing thoughtfully out into the darkness. A sudden impatience had prompted him to get rid of his rough companions, but he had no desire to sleep. The still, starlit night, the faint snowy outline of the distant mountains, the perfume of flowering shrubs, and the night odour of the pines, had quickened his senses and stirred vaguely his inherent love of beauty; so that he was forced to rid himself abruptly of his coarse surroundings and hasten out into the darkness. He leaned against the frail supports of his little dwelling, with folded arms, and dreamed—dreamed of that Eastern world which he had left, and which seemed a thing so far away from this deep majestic solitude. He turned his face towards the plains, and half closed his eyes. His had been a curious and a solitary life; a life oftenest gloomy, yet just once or twice bathed in a very bright light. It was something to think about—these brighter places so few and far between. Did he wish that he was back again where they would be once more possible? He scarcely knew! The fierce trouble and the disquiet of the days behind was no pleasant memory. He looked across, to the mist-topped hills and dark forests, and he felt that they had grown in a measure dear to him. In his heart, this great lonely man with the limbs and sinews of a giant was a poet. He was ignorant of books, and uneducated, but he loved beauty, and he loved nature, and in his way he loved solitude. He was happier here by far than he had been amongst the gilded saloons and cheap haunts of the Western cities. It was only the monotony and the apparent uselessness of his life here that oppressed him. He was a man with a purpose, a purpose which he had followed over land and sea, through cities and lonely places, with a dogged persistence characteristic of the man and of his race. In his expedition here, for the first time he had turned away from it, and the knowledge was beginning to trouble him. The hard physical labour, the glory of his surroundings, the mighty forests and hills broken up into valley, and precipice, and gorge, and all the time overshadowed by that everlasting background of the snow-capped Sierras, these things were all dear to him, and rough and uncultured though he was, they sank deeper into his being day by day, and night by night. He could not have talked about them. Nature had given him the sensibility of the poet and the artist, but education had denied him the use of words with which to express himself. As yet he scarcely appreciated all that he lost. That would conic some day.

Suddenly his dreaming was brought to an abrupt termination. His body stiffened, and his hand felt for the revolver in his belt. With the ready instinct of a man used to all sorts of emergencies, he recognized that he was no longer alone. Yonder, almost at his feet, behind that low prickly shrub, a man was lying.

"Who are you?" he asked quickly. "What do you want here? Put up your hands!"

The reply came only in a faint whisper.

"Bryan! Bryan, come and help me! Give me some brandy! I'm almost done! Thank God, I've found you!"

The Englishman stuck his revolver into his belt, and took a giant stride over to the spot.

"Who are you?" he asked, dropping on one knee, "and where, in God's name, have you come from? How do you know my name?"

The figure raised itself a little. The tattered remnants of a cap fell off, and the moonlight fell upon the wan but strangely handsome face, gleaming in the dark eyes lit up with a sudden eager light.

"Don't you know me, Bryan?" asked a soft, caressing voice. "Am I so altered?"

The Englishman gave a great start, and his bronzed face grew pale.

"My God!" he exclaimed. "It's Myra!"

The moon, which had risen now high above the wood-crowned hills, was shining with a faint ghostly light upon the new-corner's wan face. The Englishman, who had started back like a man who sees a vision, as suddenly recovered himself. Surprising though this advent was, there was no doubt as to the identity of his visitor. Neither was there any doubt but that she was on the point of exhaustion. His first duty was plain. She must be taken care of.

"Can you walk into the cabin, or shall I carry you?" he asked, in a tone as matter-of-fact as though he was accustomed every day to receive such visits. "Better carry you, I think! You look all used up!"

"I—I'm afraid I can't walk, Bryan," she admitted, looking up at him with the ghost of a smile on her lips. "I guess I fainted a bit ago! It was the sound of your voice brought me to!"

Without another word he lifted the prostrate figure into his arms, and carried her into the shanty. Arrived safely inside—he had to bend almost double to enter the doorway—be laid her on his bed, and threw a blanket over her.

Then he took up his own tin mug of brandy, found that it was half full, and forced a little between the white lips.

The effect was swift and almost magical. A little faint colour stole into her cheeks, and she opened her eyes.

"Guess I'm starved!" she remarked, with a slight uplifting of the eyelids. "Got anything to eat?"

Her eyes wandered round the place hungrily. The Englishman stood still and considered for a moment. Then he struck a match and lit an oil stove, opened a tin of beef extract, and in a few minutes had a steaming cup full of the liquid. He brought it to her side, and she clutched it eagerly.

"Drink it slowly!" he advised. "That's the style! Good God!"

He went out into the darkness, and returned in a few minutes with a pail of water. Then he turned up his shirtsleeves, and taking her shapely little feet into his great hands, bathed them carefully while she lay quite still with half closed eyes. When he had finished, he lit his pipe, and sat down by her side.

"Don't hurry, Myra!" he said, leaning back against the wall, and thrusting his hands into his pockets. "Don't talk at all unless you feel like it! More beef tea, eh? There, just a drop! That's right!"

He held the cup to her lips, and then set it down.

"If you feel like going right off to sleep, why, off you go!" he said. "You can tell me all about it in the morning!"

He spoke cheerfully, but there was an undercurrent of anxiety in his tone which the girl's quick ears detected. Henceforth she watched him furtively out of her big dark eyes, filled now with a fresh alarm.

"I'd as lief tell you now!" she said. "I'm rested!"

"That's capital! Well, how did you get here all by yourself? That's what I want to know."

A little note of triumph crept into the girl's tone. She watched her companion carefully to see what effect her words had upon him.

"I came on a mule half the way, Bryan. He died four days ago, and since then I have been walking!"

"You came on a mule!" the Englishman repeated bewildered. "Where from?"

"From San Francisco, of course!"

"My God!"

He looked at her in admiration tempered with wonder. She had expected this, and was gratified.

"Yes! You didn't think I was plucky enough for that, I guess! It's been pretty bad—worse than I thought it would be, when I started. I didn't mind so much until Johnny—that was my mule—died. He seemed sorter company, and he was a real good one. Afterwards it got lonesome, and the nights were so dark and long, I was scared sometimes. I used to lie quite still, with my face turned to the east, and as soon as the first streak of light came I could go to sleep. Then, the day before yesterday, I finished up all the food I had! I don't believe I want to talk about the time since then," she concluded, with a little shiver. "I guess I won't, anyway!"

He sat and looked at her for a moment without speaking. He was not a man of quick comprehension, and the thing amazed him.

"Five hundred miles all alone, and a beastly rough track too," he said at last. "Why, child, it seems impossible. And why on earth have you come?"

The colour rushed into her dusky cheeks, and her eyes, soft and dark now that the gleam of famine had fled, filled with tears.

"You—you are not glad to see me!" she exclaimed piteously.

He was not. That was a fact. But he began to see that it would not do to let her know it. He swore a great inward oath, but he leaned over and took her hand as tenderly as he could.

"Of course I'm glad, Myra! If you knew how beastly dull it was here, month after month with never a soul to speak to, you wouldn't wonder at that. But what beats me is, why you've come! You haven't risked your life to come to such a picnic as we're having out here! You've got a reason for coming!"

She nodded, with her eyes anxiously fixed upon him. "Yes! I've brought you something. Guess what!" His expression changed. A sudden light leaped into his eyes.

"Is it a letter?" he asked.

"Yes."

He held out his hand.

"Where is it?

"Give me a knife and I will get it," she answered.

He handed her one. She felt up one side of her tattered coat, and cut a little slit near the shoulder. Through the opening she drew a long envelope, and held it out to him; her lips slightly parted, and her eyes eagerly watching for his approval.

He took it into his hand and looked at it almost as though he feared to break the seal. It was yellow with age, and the postmark was ancient. He looked from it into the girl's face. Her eyes were full of tears.

"You are not glad that I brought it," she faltered. "It isn't of any importance after all. You haven't thanked me, you haven't said a single kind word to me, and—and you haven't even kissed me! I—I wish I had died and not got here at all!" she wound up with a little sob.

He passed his arm around her waist and drew her lips to his.

"There, don't cry, Myra," he said kindly. "I'm not an eloquent chap, you know, and I was kind of dazed. You're a regular brick, little woman, to bring me that letter. I don't believe there's another girl in the States would have had so much pluck. Cheer up now, do. Of course I'm glad to see you. You know that."

She listened to him eagerly, and gave a little sigh of relief. Then she swept the tears away, and smiled up at him faintly.

"I think I was pretty glad to have an excuse to come," she whispered in his ear. "I was weary of waiting for you to come back, and—oh, it was all such a bother. I would sooner have died than gone back to the old life, the life from which you saved me, Bryan. It was all horrid. Oh, aren't I glad I'm here! You won't send me back, will you?" she exclaimed, in sudden alarm.

"We'll talk about that in the morning," he answered. "I haven't read my letter yet. I may not be stopping here myself much longer."

"Say that I may stay as long as you do," she persisted. "Tell me that when you go, you will take me with you. Just let me hear you say that, and I won't worry you any more. I'll do everything you tell me. You say that."

He frowned and looked away from her great eager eyes on to the floor. Here was a pretty mess for him. What could he say to her?

"You'll have to be reasonable, Myra," he said slowly. "I don't see how you can stop. What on earth could I do with you? Do you know that there are four or five hundred men down in the valley there, and not a woman amongst them? How could I keep you here?

"No one would know that I was a woman," she pleaded piteously. "I would never go outside the door, if you like."

"They'd soon find out. They'd want to know why you didn't work, and what was the meaning of those pretty hands and feet," he said indulgently. "No, we couldn't keep the secret if you stayed, Myra. They're a rough lot down there, too, I can tell you. Besides, what on earth would you wear?" he added, with masculine irrelevance.

She glanced down at the rents in her rough attire, and blushed.

"You have a needle and thread here," she said. "I could patch these things up somehow. I—I brought a gown with me in my bundle there, but I suppose I mustn't wear that?"

He shook his head and glanced towards the bundle, which was lying upon the floor half-open. Something he saw seemed to him familiar. He touched it with his foot and leaned forward.

"What dress did you bring?" he asked.

Her eyes sought his appealingly, and the deep colour stained her cheeks. A little tremulous smile parted the corners of her lips.

"It is—the blue serge one, the one you liked. I had put it away until you came back. Kind of silly to bring it, wasn't it?"

He looked at her for a moment, and his own eyes grew misty. The pathos of the whole thing, as he alone could understand it, was irresistibly borne in upon him. Like a swift vision he seemed to see her struggling across that great rocky plain, day after day, night after night, fighting against the horrible loneliness, braving dangers and enduring privations which might have daunted many a man, and all the while clinging to her poor little bundle, never parting with it even in those last dreadful hours of exhaustion and despair. Poor child! He remembered the gown well. It was one which he had bought for her himself, the straight tailor-made folds pleasing his English eye. He remembered, too, how proud she had been when he had admired it, and how she had worn it on every possible occasion. There it lay before him, carefully folded and rolled up, and carried for more than five hundred miles in the hope that to see her in it might awaken some of that old tenderness which with him, alas! was almost a thing of the past. He looked into her strained, plaintive face, and did what, as yet, of his own accord he had not done or desired to do. He kissed her.

She laughed softly, and glanced up at him from his shoulder, pointing to her clothes.

"Do these things look very awful?"

He affected not to notice the look which pleaded for some consoling speech, and gently detaching himself from her embrace, he stooped down and drew from underneath the plank bed a long white linen coat which he had bought in San Francisco, but had found far too small for him. He shook it, and held it out to her.

"They want stitching, then they'd be all right," he declared. "You'd better put this on for a bit, and try to go to sleep. You've talked more than enough now, and you look deadly tired. Good night."

She sat up and looked at him for a moment, but he kept his head turned resolutely away.

"Where are you—going to sleep?" she asked quietly.

"Outside. I generally do. We are too high up here for the dews to hurt, you know. Call out if you are frightened, or if you want anything. I shall hear you."

"Thank you. Good night, Bryan."

A little break in her voice smote his heart. He thought of the long lonely nights of terror through which she had passed, and he was troubled. He felt a brute. For a moment he hesitated. Then he took one swift step across to her side, and kissed her tenderly.

"Good night, Myra," he said. "God bless you!"

She laughed a little. Blessings sounded oddly in her ears, but the kiss was more like old times. So she did her best to console herself with it, slipping off her soiled clothes and curling herself up on the bed. In a few moments she was asleep.

It was the end of her pilgrimage. She had risked her life, had faced a loneliness as awful as the loneliness of death, and had cheerfully borne the most terrible hardships to bring him the letter—and herself; and now that her task was at an end she lay stretched upon his hard plank bed, dreaming as peacefully of the happiness of being once more with the man she loved, as though the bed were of down, and the hut a palace. And outside, within a few yards of her, the Englishman lay face downwards upon the short dry turf, cursing alike his past folly and his present weakness. His letter lay unopened by his side; for the moment he had even forgotten it. Whilst he had been with her he had striven hard to hide his feelings; but now that he was alone in the darkness he looked this thing in the face, and the longer he looked the less he liked it. It seemed only the other day that he had made his escape; that he had willingly, nay, eagerly, turned over that short chapter of his life, and with intense relief had told himself that it was a past dream of folly, over and done with for ever. It was one of fate's grim jests, an everyday affair. But it seemed a little hard upon her.

After a while he sat up, lit a pipe, and tore open the envelope of his letter. The moonlight was just strong enough to enable him to decipher it slowly.

"18, MARLOWE COURT, STRAND, LONDON, W. C.

"August 17th.

"DEAR SIR,

"After considerable trouble and some expense, we have become acquainted with

some further details concerning the man, Maurice Huntly, who visited you at

Denton on the first of last month. We find that his real name is Marriot, and

that seven years ago a warrant was issued for his arrest on a charge of

forgery. The warrant was never executed, as he fled the country, but, on his

recent visit to England, the police obtained some clue as to his identity,

and were on his track. It was to escape from them, and not to avoid

completing his disclosures to you, that he quitted England so abruptly. We

trust that this will enable you to come across him in the States, as he

certainly has no object in keeping out of your way. We believe that he took

another name in New York, but that you will doubtless have ascertained for

yourself. Our information further goes to show that he was the son of a

clergyman, and started life with every advantage. Should anything further

transpire we will let you know. In the meantime we remain,

"Your obedient Servants,

"MASON AND WILLIAMS.

"P.S.—It is never our desire to extract from our clients an unwilling

confidence, but at the same time, we cannot refrain from submitting to you

that we should be in a far better position to work on your behalf, if we

possessed sonic information as to the nature of the disclosures so important

to yourself, referred to by the man Marriot during his brief visit to you at

Denton."

He read it through twice, and remained for some time afterwards deep in thought. Then, with an effort to conquer his restlessness, he lay down, pulled a rug over him, and tried to sleep. Through half-closed eyes he watched the fireflies gleaming in the valley below, and listened to the faint, lulling music from the pine forest away overhead. Gradually he grew drowsy. He was almost dozing, when a sound close at hand disturbed him. The door of the shanty was softly opened, and Myra came out.

She walked noiselessly towards him, with bare feet, and wrapped in the long white garment which he had given her, and which certainly had never seemed destined to fall into such graceful folds around so dainty a form. He caught one glimpse of her dusky face, strangely soft in the waning moonlight, the lips a little parted in a faint smile, and the deep, glowing eyes full of a wonderful liquid fire; and he realized as he had never done before the wild, strange beauty of the girl who was stealing like a ghost to his side. Then he closed his eyes and breathed heavily.

She stooped down till her warm breath fell upon his bronzed, sunburnt cheek. Then, seeing that he made no movement, she gave a wistful little sigh, and kissed him so lightly that her lips seemed scarcely to brush his. Still he did not move, or give any sign of wakefulness. Presently he felt her sink down by his side, and her head drooped upon his shoulder. In a few moments she was asleep. As soon as he was sure of it, he threw the rug over her, and rising softly, walked away in the darkness.

By six o'clock in the morning a bright sun, mounting into a sky of dazzling clearness, began to make its power felt. An hour later the Englishman, who had been working on his claim since the first gray streaks of dawn, took off his clothes and plunged into a deep pool of the river. Emerging, he dried himself leisurely, dressed, and scrambled up the gorge side to the small platform of green turf on which he had built his cabin.

His guest was at the door in her cowboy's clothes, patched and mended up. She welcomed him with a little cry of delight, and then a swift, deep blush, as she saw his lips part with amusement.

"That's real mean!" she declared. "It's bad enough to have to wear such things, without being laughed at. I shall go and put on my gown!"

He laughed outright, pushing her before him into the cabin, and glancing apprehensively down into the valley, and across to the opposite shanty. There was no one in sight.

"You won't do anything of the sort, if you please," he said decidedly. "You look very well as you are. Come and let's get some breakfast. I'm starving!"

"It's ready and waiting—all that I can find. Bryan, this is the most elegant place in the world. I never saw anything half so beautiful."

He turned round and stood by her side in the doorway, looking across the valley to where a dim blue haze shrouded the distant mountain-tops. In the pure, fine air all colours seemed intensified—the green of the alder and hazel-trees rising sharp and clear against the sky, and the deeper shade of the broad belt of pine-trees which fringed the mountain's side; a great flowering cactus with bright scarlet blossoms drooped over the precipice below, and the rocks and bushes were starred with flowers of strange and brilliant colours growing out of every crack and in every corner. The dry morning air was sweet, too, with the perfume of many herbs and flowers, and far down in the valley the sun-smitten river gleamed like a bed of silver. The girl, to whom nature in such a guise as this was a revelation, stood there with bright, thoughtful eyes, and with the languid morning breeze stealing through her dark wavy hair, no longer coiled up and concealed. She was feeling the touch of a new power in the world, a new sensation. Hereafter she sometimes associated a new phase of life into which she was to pass, with this morning.

"I like this!" she said softly. "It's better than the city. I'd like to live here always!"

The Englishman frowned.

"You'd be tired of it in a week, Myra. No shops, no theatre, no drives in the park! I doubt whether you'd stand it for a week. Come along, and let's see what you've made of breakfast."

The girl turned away with a sigh, and followed him into the shanty.

"I've found some tea," she said, "and some bacon—I cooked that. The stove don't go very well; guess it wants cleaning."

"That's all right. Things look real tidy for once. Sit down and let us have some breakfast. Afterwards I want to talk to you."

She obeyed Him in silence. Her cheeks had suddenly grown pale again. She ate but little, watching her companion most of the time. What was he going to do with her? Would he send her back after all—away from him, and back to the life she hated with a great soul-shuddering hate? Oh, he would not be so cruel as that; surely he would not! Go back to that great hideous city with its garishness and glitter, its cheap vice and all its brazen show of falseness and iniquity! She had drifted there on the broad bosom of an unkind fate; a fate which should surely have marked her out for better things. Vice had no allurements for her. The pleasures of the demi-monde, the cheap theatre and the tawdry dancing saloon, were flavourless to her. She thought of them now as she gazed out at the glorious blue sky, and the panorama of bold and magnificent scenery, with a shudder which came from her very soul. The sweet scented breeze which swept in through the open doorway, tasted to her jaded senses like the elixir of life. A passionate disgust of cities and all their ways leaped up within her. From that moment the life of the past had become impossible to her. She had been born one of nature's children outside the ken of cities, almost of civilization, and it was but the return to an old allegiance.

The Englishman had finished his breakfast, calmly unconscious of all that was passing through the mind of his companion. He lit a pipe, dragged the form into the sunshine, and motioned her to sit at the other end of it.

"Myra," he said gently, after a few moments' meditative silence, "you've done me a real good turn. You've shown uncommon grit, and you've accomplished a thing which a good many men wouldn't have cared about. I haven't said much about it; I was so surprised to see you last night that you might have thought I wasn't grateful. But I am. I want to show it, if I can. I want to repay you so far as a man is able to repay a service of that sort; and so—"

"I want no repayment—only to stop right here," she interrupted breathlessly. "I should be perfectly happy. I could look after things and cook for you, and keep the place clean, and—oh, Bryan, for God's sake, let me stop! You were fond of me once—anyway, you used to tell me so. Don't drive me away! I don't care how you treat me. I will be your slave if you like—nothing more. Only don't send me back! Let me stay, Bryan! Do let me stay!"

She had slipped from the form on to the ground, and was kneeling at his feet, her eyes bright with tears, and the colour coming and going in her cheeks. She even ventured to lay her arms imploringly on his shoulders, and turn them round his neck. The Englishman gently unwound her fingers, retaining possession of one of her hands. He looked down into her flushed face with a troubled shade in his own.

"Myra, it wouldn't do," he said kindly. "You'll think me a brute, of course. Dare say I am. But I want you to leave here with the expressman, the day after to-morrow, and go right back to San Francisco. I can't keep you here, little woman, if I wanted to; and if I could, I wouldn't, so there!"

Her bosom heaved. She drew herself right away from him, and stood leaning against the wall, with a crimson colour in her cheeks and her eyes afire.

"You—you don't care for me any more, then? It was true, what I feared! You came here to get rid of me. You were tired, you wanted to escape."

"Steady, Myra. You know that's not right. I came here for two reasons. First, to make money. Secondly, because I was satisfied that the man whom I had come from England to find, was not in San Francisco. I had no trace of him, nothing to go by. I thought to myself that if he was the restless sort of chap every one made him out to be, he would most likely be off on the gold fever, like the rest of them. That's why I came, Myra. It's all very well for me here. I'm a rough sort of chap, and I can find my level anywhere, but it's not the place for a woman."

"Any place is good enough for such as I!" she cried passionately. "It's only an excuse; you want to get rid of me. You do! And I have come all this way just to see you, just to bring you that letter. Just to be with you! Oh, I hate myself! I hate you! I wish I were dead!"

Her eyes strayed to the revolver which lay upon the table. She made a quick movement towards it, but he caught her wrist and held it firmly.

"That'll do, Myra," he said firmly. "Just listen to me. If I am brutal it is your own fault—so here goes. You came to me of your own free will—ay, of your own accord. Is it not so? I met you in Josi's cafi at San Francisco, whilst I was idling about waiting for—you know what. Well, you came and kept house with me for a month or two. I was not the first. You told me so yourself. The thing was common enough. I never made you any promises. I never gave you to understand that it would be likely to last. When I heard that the man for whom I was lying in wait had left the city, I gave you notice that I was off. Well, you were sorry, and I was sorry. I shared up all that I had in the world, and I left you. I may have made you some sort of promise about coming back again, but never as a permanency, you understand. I'm as fond of you now as I ever was—fonder, if anything, after what you've done for me—but you must take this little affair with me as you took the others—see? Now I've made you feel badly. I'm sorry, but I'd got to do it."

The changing shades in the girl's countenance had been a study for which many an eastern painter would willingly have bartered every model in his studio. At first her dusky face had darkened, and her eyes had blazed with all the wild free fury of a woman whose vanity, or love, or both, are deeply wounded. But as he went on, as the whole bitter meaning of his words, winged with a kindness which seemed to her like the poison on the arrow's tip, sank into her understanding, the anger seemed to die away. When he had finished she was crouched upon the ground with her back to him. She did not answer him or address him in any way; only he knew that she was sobbing her heart out, and, being by no means a stone, he began to relent.

"Myra," he said kindly, stretching out his hand and laying it upon her shoulder, "come and sit with me for a minute or two before I go! I must be off to work again directly, and I can't leave you like this."

She got up meekly, dried her eyes, and sat at the extreme end of the form, with her hands folded in her lap, and gazing listlessly out of the open doorway. Alas! the music of the winds and the deep, soft colouring of the hills and far-off mountains were nothing to her now! All the buoyancy of life seemed crushed and nerveless. Even that sudden strong, sweet joy in these glories of nature which had leaped up in her breast, a new-born and joyous thing, was dead. Watching her as she sat there, the Englishman felt like a guilty man. He had made some clumsy attempt at doing the thing which seemed to his limited vision right and kind. He was not accustomed to women or their ways, but he felt instinctively that he had made a mistake somehow. A sense almost of awe came upon him. He felt like a man who has destroyed something immeasurably greater than himself; something so grand that no power in this world could build it up again. He was penitent and remorseful, even sorrowful, without any very clear idea as to what this evil thing was that he had done. Only he looked into this girl's downcast face, and he felt like some wanton schoolboy who has dashed to the ground one of those dainty, brilliant butterflies with peach-coloured wings, and a bloom so beautiful that a single touch from coarse fingers must mar it for ever. A moment before it was one of God's own creatures, a dream of soft elegance and refined colouring. Now it lies upon the ground bruised and shapeless, fluttering its broken wings for the last time, and breathing out its sad little life. In a minute or two some passer-by will kick it into the dust. That will be the end of it. The Englishman looked at the girl by his side, and his eyes twitched convulsively. There was an odd lump in his throat.

"Myra, I don't want to be a brute!" he said softly. "I want to act squarely to you. That's what makes me seem unkind, perhaps. I'm quite unsettled here! I've heard nothing of the man I'm in search of, but directly I have found him, I shall be leaving the country for good. It wouldn't be fair to take up with you again, would it? You're not like the others. I wouldn't mind if you were!"

She shuddered and looked up at him, dry-eyed and callous. "You are quite right! I do not want to be a burden upon any one!" she said slowly. "I am ready to do just what you think best. If you like, I'll go back the same way I came. I dare say I could find it all right. If not, it wouldn't much matter!"

The dull despair of her tone, and the mute abandonment of herself to his wishes, moved him strangely. For the first time he hesitated. He had been prepared for reproaches, he had steeled his heart even against her tears, her caressings, her beseechings; but this was something quite different. From feeling altogether in the right, he began to wonder vaguely whether he was not attempting something singularly brutal and unmanly. He hesitated, and every moment the words which he desired to say became more impossible. He turned to her abruptly.

"Aren't you just a little rough on me, Myra?" he said softly. "Don't you see that it is for your sake I wanted to go!"

She looked at him, and his eyes fell before hers. "For my sake!" she repeated bitterly.

He began to feel absolutely conscience-stricken. After all, the reproach in her tone was just. It was as much for his own sake as hers that he had wanted to be rid of her. There was an element of Puritanism in the man which rebelled against all the irregularities of this wild western life. He liked to be his own man and live his own life! Well, he should have been consistent! Here was a harvest of his own sowing. If his heart had not been moved by the wild, beseeching pathos of this girl's dark eyes shining at him through a cloud of thick tobacco smoke in Josi's saloon, he would never have found himself in such a quandary. Bah! it was useless to waste time on empty regrets, to rail at the past while the girl's heart was breaking. He got up, and bent over her.

"Look here, Myra," lie said kindly. "I guess I'm not so sure about being right after all. I'll think it over whilst I'm at work. See? Don't fret! We'll see if we can't fix up something."

"Very well."

He relit his pipe, and kissed her hesitatingly upon the forehead, a salute which she accepted with perfect impassiveness. Then he strode out of the cottage, and down the gorge to the river-bed.

Three men, the last to leave their claims after the day's work, climbed up the gorge in the heavy twilight. The Englishman and his partner were a little in front, Mr. James Hamilton brought up the rear.

At the parting of the ways they were separating, as usual, without a word, when the Englishman looked back over his shoulder.

"No cards to-night, you chaps—not at my shanty, anyhow!" he said briefly. "Do you hear, Jim?"

"Yes, I hear!" Mr. Hamilton repeated surlily. "You want me to sit and get the miserables in this cussed hole! I'll see myself d—d first. If you chaps ain't playing I'm off to Dan Cooper's saloon. Who the hell's that dodging about your hut?" he added, peering upwards through the brambles. "Here goes for them, at any rate! I'd shoot anything to-day, from a dog to a Christian!"

He raised his gun to his shoulder with a savage scowl. The Englishman stooped down quickly and knocked the barrel into the air, where it exploded harmlessly.

"I'll do my own shooting, thank you, Jim!" he said carelessly. "I've got a stranger up there, a boy who's found his way from San Francisco. You can go to Cooper's store if you like, and be fleeced, and catch a fever, and get drunk on poison at a dollar a glass! It's no business of mine, but if you take my advice, you'll stop where you are and go to bed early for once! There's enough blackguardism going on down there, without your being mixed up in it."

Mr. Hamilton turned his back on them with an oath, and disappeared. The Englishman and his partner scrambled up the opposite side of the gorge, to the platform where they had built their shanties about a hundred yards apart. Arrived at the top, Pete Morrison thoughtfully hitched up his trousers, and spitting out a tobacco plug, laid his hand upon the other's shoulder.

"Mate!" he said deliberately. "I seed that stranger."

The Englishman turned quickly round.

"Well, what if you did?

"Not much! It ain't a female, is it?"

The Englishman was beginning to lose his temper. He answered testily, even angrily.

"What the devil does it matter to you or to any one else, who my visitor is! I suppose I may have whom I like in my own shanty."

Pete was quite unmoved, although his face had grown a shade more serious. He took off his cap, and began flicking away a few stray mosquitoes.

"No offence, pard. But ain't you heard what Dan Cooper and his lot have give out?"

"No."

"Well, they allow they're going to run these diggin's on a new tack. Dan was at the Black Creek lot, and I guess you know what a hell that place was turned into. Well, they allow that the first woman who shows here, out she goes and him as brought her, claim or no claim. That's what they say down yonder," he added, jerking his thumb downwards in the direction of the camp. "That's what Dan Cooper and his chaps do say, and I reckon they're strong enough to run this section."

"That's so!" the Englishman answered, frowning. "Thanks, Pete! I'll take care! Better be mum about my visitor, anyway."

He walked away up the little green path, and pushed open the door of the hut. He scarcely knew the place. It had been cleaned and swept, and his evening meal was prepared. Myra was sitting in a corner, mending some old garment of his.

He greeted her kindly, but without going over to her side.

"Well, Myra! been lonesome, eh?" he asked.

She flashed a single look up at him from her brilliant eyes, and bent again over her task.

"Sorter lonesome," she assented. "I've been busy fixing up things too!"

"Looks like it," he answered, glancing around. "Let's have supper! We've had a nailing hard day's work!"

She got up without a word, and seating herself opposite to him, poured out the tea from a tin pot. He ate and drank with characteristic appetite, and she made a show of following his example. When he had finished, she cleared away, and then came and sat down by his side.

"Have you fixed up when I am to go?" she asked quietly.

She turned a pale, anxious face towards him, and sat patiently waiting for his answer. It was long in coming. He had begun dimly to see what the end of it must be; but even at that last moment he felt a curious reluctance to re-entering into the bondage of her love for him. He leaned back on the bench, and looked at her, wondering at the peculiar inappropriateness of her rude and ill-shaped clothes with that strange, delicate beauty which was so essentially dainty and feminine. His heart beat a little faster as he looked into her soft dark eyes with their silky eyelashes, and noted, with some return of his old admiration of her, the quivering sensitive mouth, the great coils of waving glossy hair, and the perfectly graceful curve of her throat and neck, gleaming as white as marble in contrast with the low black shirt she wore. The power of her beauty had always been great over him, and he was beginning to feel a sudden and altogether undesired revival of the curious fascination which once before she had possessed for him.

"I have been inquiring about the expressman," he answered. "Seems I was out in my reckoning. They say he's not due for three weeks or so."

She lifted her eyes, and watched him covertly. He had not seemed in any way disappointed or disturbed at the prospect which was before them. Perhaps, after all, he was not so very sorry. He was only human, and the fierce solitude of the long nights, with their almost brutal relaxations of cards and raw spirits, had filled him with a great intolerable weariness. In the day-time when work was possible, the life was, at any rate, bearable. But the darkness came early, and the evenings were long. He had no books, nor any inclination to read them. The man's nature was too large for him to keep himself aloof from those others, his fellow-workers, and besides, he had not the capacity for solitude. He was one with his fellows; a man with all the instincts of a common and gregarious humanity.

Through the long day and in the intervals of his toil, he had been thinking of these things. What had been gall and weariness in the city presented itself here, and under these conditions, in altogether a different aspect. He might truthfully say, if ever his conscience should reproach him in the years to come, that he had done his best to rid himself of this girl's presence. He had failed! It was fate! She had drifted to him again, a flotsam on the broad river of humanity, herself controlling the current which bore her into his arms. After all, he was but passive in the matter. Even had he desired it, escape would not be easy, and in his heart he was not at all sure that he did desire it. In San Francisco he had found life with this girl in curious antipathy to all his crude notions of what was seemly and honest. A strong and never conquered dislike to their mode of living chafed him from the first. He had not a particle of religion, nor any conscious love of morality. He went into his bondage perfectly untrammelled by any scruples other than instinctive ones. But in a week he was conscious of but one desire: to free himself from a connection which was utterly distasteful to him as speedily as possible; and it was in a measure the reaction from the enervating period of his brief liaison which had led him to throw in his lot with a handful of men bound for the gold region. In the shadow of the great mountains, face to face with Nature in all her primitive grandeur, he had become himself again. The hard physical toil had been a luxury to him. He had already learned to think kindly, almost with regret, of the girl who had so suddenly returned into his life. What a difference her presence seemed to make in the miserable little shanty! He was forced to admit it. His day's reflections had all been favourable to her. Even had he desired it, escape now would not be easy.

Perhaps she guessed by his face and his tone, that he was relenting in his demeanour towards her. Womanlike, she took advantage of the opportunity. She glided across the room, and fell upon her knees before him.

"Don't send me away, Bryan!" she begged. "Don't! Don't!"

She was sobbing hysterically at his feet, crouching there, her hair and dress disordered, with all the sinuous grace and elegance of some beautiful wild animal. Then he took her hand, and hesitated for the last time. Slowly he stooped down, and wound his arms around her, raising her towards him. With a little soft cry she twined her fingers around his neck, and buried her face upon his shoulder. Then he drew her lips to his and kissed her.

They were silent for a few moments, gazing out into the rich, soft darkness, which spread itself like a mantle below them. Down in the camp they could hear the mingled sounds of revelry at Cooper's store, and the steady hammering of some new arrivals marking out their claim and setting up tents. It was early for the moon, and the fireflies like flashes of gold darted up and down the sides of the steep ravine, and hung like tiny stars over the valley below. Suddenly from the other side of the cleft a red flame leaped up hissing into the night. Myra started and looked breathlessly out into the darkness.

"It's only Jim Hamilton—the chap who has the shanty opposite," the Englishman explained. "He's on the borders of a wood, you see, and he's afraid of bears. He burns pine boughs there, every night he's alone!"

Another tongue of flame leaped up, and now they could hear the crackling of the burning branches. Another and another followed. Myra leaned forward, holding her breath, and fascinated for a moment by the curious sight. Even the man whose arm was round her supple waist was interested. The whole air was full of that fitful yet brilliant light casting a vivid glow upon the undergrowth and down into the precipice hung with tiny fir-trees, and throwing back strange lurid shadows upon the red-trunked trees and the dense blackness of the wood. Mr. James Hamilton himself, who was alternately feeding and raking the fire he had kindled, bathed in the rich scarlet glow became almost a picturesque object. Suddenly, as though conscious of being observed, he stood upright and turned towards them, leaning on his shovel, and slightly shading his eyes with his hand.

A great tongue of red fire scattered a thousand sparks, and leaped up into the black night. For a moment every line and furrow in the man's evil face stood revealed. The disclosure was startling, almost sinister. Even the Englishman, who had sat opposite to the man for months, shuddered and turned away. For a few seconds he forgot his companion. Then a stifled cry from his side, and an added weight upon his arms, reminded him of her with alarm. He caught her up in his arms and bore her to the bed. Her face was white and her eyes were closed. She had fainted.

And across the gorge, bathed in a stream of red fire, Mr. James Hamilton stood there like a carved figure, with a light more brilliant than the flaming pine boughs had ever cast, blazing in his eyes, and a fire more fierce than that which had made white ashes of the dry wood, burning in his evil heart. Then he dropped his hand and burst into a hoarse ringing laugh, a laugh which echoed up the gorge and down the valley, and came even to the ears of the men sitting in Dan Cooper's store. One cursed the jackals, and another spoke of wolves. But the laugh was the laugh of Mr. James Hamilton.

It was morning. As yet the sun had gained no strength, and though the air above was clear and bright with the promise of a glorious day, a mantle of hazy white mists floated in the valley, and hung over the tree-tops. Mr. James Hamilton, after throwing a careful glance around, slipped out from his cabin, scrambled down the gorge and up the opposite side, and walked softly along the garden path which led to the shanty.

The Englishman had gone to the river—he had watched him go. Only his visitor was there. As he approached within a few yards of the shanty, Myra, who had just risen, came to the door to watch the sun strike the tops of the distant Sierras. Instead, she looked into the dark, evil face of Mr. James Hamilton.

She started back with a little low cry. The colour faded from her cheeks and the glad light from her eyes. A sudden faintness came over her. Sun and sky, wooded gorge and rolling plain, commenced to dance before her eyes. She felt herself growing sick and numbed with horror. Last night she had persuaded herself that it was a delusion. The shadows and the dim light had made her fanciful. But here in the clear morning's sunshine, where every object possessed even an added vividness, there could be no possibility of any mistake. The man whom it had been the one fervent prayer of her life that she might never see again, was face to face with her alone in these mountain solitudes.

And he had not changed—not a whit. There was the same cold, ugly smile, the same fiendish appreciation of the loathing which he aroused in her. He took off his battered cap, and made her a mock obeisance.

"You—here!" she gasped. She felt that she must say something. The silence was intolerable. It was beginning to stifle her.

"You've hit it!" he remarked. "Did you think I was a ghost? Feel! I'm flesh and blood! Come and feel, I say!"

He held out his arms with a gesture of coarse invitation. She shrank away with a little cry which dropped into a moan—almost of physical pain.

"Don't touch me! Don't dare to touch me! What do you want?"

Mr. Hamilton appeared hurt. His manner and his tone implied that he had expected a different reception.

"What do I want? Come, I like that! You don't mean to tell me that you've come to this God-forsaken hole of a place after some one else, eh? When I saw you last night, I thought at first of coming right over and claiming you. It's me you came for, I reckon. Ain't it, eh?"

Her eyes flashed fire upon him.

"Come after you!" she repeated, her bosom heaving with pent-up emotion. "Oh, my God! I would sooner walk into my grave. To look at you—and remember, is torture! What do you come here for? How dare you come into my sight!"

He laughed; a low, sneering laugh that had little of merriment in it.

"So it is the Englishman, is it? Now listen here, my sweetheart, and don't ruffle your pretty feathers. If we were in San Francisco, or any place where there was a choice of society, you could take up with whom you liked and be d—d to you; but out here it's different! You're mine, and I mean to have you! Do you hear? This blasted hole has given me the blues. I'm lonely, d—d lonely, and 'pon my word, you're a devilish handsome woman, you know! It won't be for long. I shall soon be as tired of you as I was before, and then you can come back to your Englishman! No nonsense, you little fool! You belong to me, body and soul, and I'm going to have you!"

She had not been able to attempt any escape, had any been possible. The man's very presence seemed to have bereft her of all strength. She stood there fascinated with the deep unspeakable horror of it, trembling from head to foot, and miserably conscious of her own impotence. Before she could recover herself his arms closed suddenly around her, and his hot breath scorched her check as he stooped down and lifted her bodily into his arms. She gave one despairing shriek, and then a cry of joy. There was a slow, deliberate footstep outside, and a tall form stood upon the threshold. Mr. Hamilton dropped his burden, and turned round with a fierce oath.

It was Pete Morrison who was lounging there, lank and nonchalant, with a pipe in his mouth and his hands in his pockets.

"Hello! What's the shindy!" he inquired good-naturedly.

"It's no affair of yours," answered Mr. Hamilton, with savage emphasis. "Stand aside and let us pass, Pete Morrison. I'm not the man to be trifled with, and I'll stand to my word to-day. Out of my path, or I'll let daylight into you, sure as hell!"

Pete Morrison stood a little on one side, and blew a volume of tobacco smoke from his mouth.

"Where's the hurry?" he inquired. "I ain't standing in your way. You may go as fast as you like, but I kinder think you'd better leave the boy," he added mildly.

"The boy's mine. Clear the way, I tell you!"

His hand stole down towards his belt. Quick as lightning Pete Morrison's hand flashed out towards him.

"Hands up, Jim."

Mr. Hamilton obeyed the order, and saved his life. He still looked into the dark barrel of Pete's revolver, but the pressure on the trigger was relaxed.

"Now look here, Jim," Pete Morrison remarked calmly. "I'll allow that this ain't none of my affairs. I interfere only as far as this. While my pard's away, no one don't enter his shanty, nor meddle with his property—not if I'm around, anyway. If this 'ere boy belongs to you, come and fetch him while Bryan's here. That's all. Now I reckon you'd better quit. You seem to have scared the life out of the young 'un."

Mr. Hamilton was white with rage. He walked sullenly to the door and then turned round.

"Very well, Pete. Your turn now, mine next. I'm off to the creek. What was it Dan Cooper proposed, and Pete Robinson seconded, eh?" he sneered. "No women in this 'ere camp. And you and your d—d partner thought you'd make fools of us all by calling that a boy, eh? Ha! ha! ha! We'll see. Mark my words, Pete, my fine chap. Before to-morrow's sun goes down, you'll be advertising for a partner. Ha! ha!"

He turned away. Suddenly a faint voice recalled him. He looked round. Myra was standing in the doorway, pale and trembling. She laid her hand on Pete Morrison's coat-sleeve.

"Is that true?" she whispered hoarsely. "Tell me quick."

"Reckon so," Pete answered gruffly.

He had done his duty to his partner, but he had no friendly feelings towards this stranger. She turned towards Mr. Hamilton, who was watching her with an evil smile.

"Will you wait a little time before you go down and tell them in the camp?" she said, in a dull, lifeless tone.

"Four-and-twenty hours," he answered briefly. "If you are with me to-morrow morning before the sun touches yonder ridge, I am silent. If not—you know."

He sprang down the gorge side and disappeared. Pete Morrison had also gone back to his shanty without another word to the stranger whose presence he found so unwelcome. Myra was alone.

She sat down upon the little bench and looked out with blind, unseeing eyes on the sun-smitten woods and the valley still overhung with faint wreaths of fairy-like mist. Alas, all their sweetness was gone for her. A great black shadow lay across it all. Shuddering, she dared for a moment to glance back at those awful days which for years she had been striving to forget; days of horror, and degradation, and sin, days almost of madness. She had climbed a little way out of hell, only to be thrust back again by the same hand that had 'dragged her down. She knew no God. She had no friend. There was no way for her to turn, nothing but death. She stretched out her hand, and thrust the small revolver which she had brought with her from San Francisco into the bosom of her gown. She had been very near it twice before: once when her first trust had been betrayed, and again in the desert when gaunt famine had stared her in the face. This time it seemed to her that death would be an easier thing. The man who had shown her the blackest and most hideous depths of human depravity was breathing the same air. Better death by the slowest and most awful tortures than that his hand and hers should ever meet again upon this earth. Better a hell of everlasting torture than such a hell as this. She stretched out her hand with a convulsive, dramatic gesture towards the little brown shanty on the other side of the gorge, and her lips moved in an unspoken oath. The sweet, sharp air into which she looked was rent by the single word which burst from her tightly-compressed lips: "Never!"

Soon after eight o'clock, the Englishman, with his spade over his shoulder, and the perspiration streaming from his face, came toiling up the gorge, all unconscious of the fact that he was being watched by three people. Mr. Hamilton, duly prepared for any little unpleasantness that might take place, was skulking in the dark interior of his shanty, with a long knife in his belt, and his revolver on the table before him. He had no intention of going down to work until he saw what was to be the result of his morning's expedition. In public he felt that any contest between the Englishman and himself would have to be conducted according to the camp's notions of fair play. Here, on the contrary, he would have full advantage of certain methods known only to himself and in which by frequent practice he had attained a singular proficiency. So he sat smoking his pipe, and watching the tall, stalwart figure climbing up the valley, with a grim smile on his dark face.

There were two others who watched his progress. Pete Morrison, who stood at the door of his cabin, equipped for the day's toil, and ready to start off and take his place; and Myra, who was of the three certainly the most anxious. Directly she saw Pete Morrison step out as though to intercept his partner, she hurried forward to the edge of the gorge, and waved both her hands to hasten him on. If she had felt sure of her footing, she would have scrambled down to meet him Anything to have reached him first—anything to prevent the knowledge of the morning's adventure reaching him from any one else save herself.

She took one step down the gorge, steadying herself with a low-hanging alder bough. The Englishman saw her, and waved her back.

"Hold on!" he cried, in surprise. "I'm coming!"

"Hurry, then!" she called back. "Breakfast is just spoilt!"

Pete, too, had taken his pipe from his mouth, and seemed about to address his partner, now immediately below him. At the sound of the girl's voice, however, he paused and glanced up to the broad green platform on which she was standing, her hair waving in the breeze, and her slim figure clearly outlined against the blue sky. He was too far away to read her expression, but something in her voice and her quick, anxious glance in his direction struck him curiously. He checked his forward movement, and contented himself with a gruff good-morning, as the Englishman passed on below, and commenced to scramble up the gorge.

"Going down, Pete?" he called out.

"Right away!" was the brief reply.

"Hold on a bit!"

He lounged forward to meet his partner, who was scrambling up towards him. During the interval of his waiting, he glanced up to where the girl was watching the two men, in a manner which he meant to be reassuring.

"She'll tell him right enough," he reflected. "Guess she'll try and smooth it down. Just as lief she would! Hullo, mate, what's up?" he added aloud.

The Englishman's face was all aglow. He had something tightly clenched in his left hand, and after a quick glance around, he held it out towards his partner, and slowly unclasped his fingers. Even Pete Morrison's set features relaxed for once. A gleam of enthusiasm shone in his hard face. Then he glanced suspiciously over towards Mr. Hamilton's abode.

"Keep it snug!" he said coolly. "I ain't seen Jim go down this morning, and I'd just as lief he didn't know of this, yet. Any more?"

"Heaps! More in my pockets. It's the biggest find yet!"

Pete Morrison looked away for a moment, and his coat-sleeve brushed across his eyes. He had turned towards the Blue Hills, but he saw only a woman's worn, pale face, thin and harassed, yet with a soft, pleasant light in the keen gray eyes. It was gone almost directly.

"I was thinking—of my old woman!" he remarked apologetically. "It seems kinder hard!"

The Englishman made a gesture as though to stretch out his hand. Pete stopped him.

"Thank 'ee, mate!" he said hurriedly. "We won't shake. I guess that Jim's watching us from yonder. He's a bad lot, is Jim—a cursed bad lot!"

The other nodded silently, and they separated. Pete shouldered his spade, and after one more doubtful glance at the slim figure watching them so earnestly from the summit, slouched off. Myra watched him with relief. He had not told. A single glance in the Englishman's face was sufficient to assure her of that.

"Hungry, little woman?" he cried out cheerfully, throwing down the spade, and drawing her into the shanty. "Come inside, and hear some news!"

He pulled the door to after them, and drawing her pale face up to his, kissed her once or twice.

"You've brought us luck, after all, you little puss!" he said heartily. "Sit down and give me my breakfast. I want to be off back at work. Look at that first, though!"

He held out his left hand, and she saw a lump of dull brown metal here and there glittering brightly. She balanced it in her fingers and gave it back to him.

"Is it gold?" she asked, half-fearfully.

"Gold! Ay, to be sure it is," he answered, "and gold such as hasn't been found hereabouts yet. There's more, too, heaps more—piles and piles of it. My God! To think of its coming so suddenly as I was on the point of giving up! It's wonderful!"

He was standing up in the centre of the hut, his eyes gleaming, and his whole face lit up. The fever of the thing was upon him. After so much useless toil, success such as this was intoxicating. His companion's apathy amazed him.

"Don't you understand, Myra?" he exclaimed, passing his arm around her. "We're going to be rich, going to have heaps and heaps of money. This little brown nugget here," he went on, touching it enthusiastically, "means the key to another world. It means diamonds and Paris dresses and a carriage for you, and for me, more than all that! For me—"

He stopped abruptly. A dark shade had stolen into his face; the light had died away. It was several moments before he spoke again.

"Yes, it means more than all that for me!" he added quietly. "It shall mean it. With this gold to aid me, I shall succeed. Come, Myra, breakfast! I must be off again!"

He ate and drank heartily, but a curious abstraction seemed to have settled down upon him. Every now and then he muttered to himself. Myra watched him with tears in her eyes. He was taking no notice of her whatever.