RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

"YOU are—Milord Cravon?"

I admitted the fact meekly, but with a lamentable absence of dignity, being, indeed, too utterly amazed for coherency. Whereupon my visitor raised her veil, flashed a brilliant smile upon me and sat down.

"I was sure of it," she remarked, speaking with great fluency, but with a strong foreign accent. "Milord's likeness to his brother is remarkable. I am very fortunate to discover you so early. It is but half an hour since I reached London."

That she had discovered me was obvious, but how or why was more than I could imagine. She was a complete stranger to me, she had entered my rooms unannounced, and the little French clock upon my mantelpiece had just struck midnight. However, she had mentioned my brother! I spoke of him at once.

"You know Reggie, then?" I inquired.

"I have met Mr. Reginald Lessingham once or twice," she admitted.

"At Marianburg?"

"At Marianburg—and elsewhere!"

"You have come from there?" I asked.

She nodded, and loosened her travelling cloak.

"I left Marianburg," she said, "exactly forty hours ago. It is rapid travelling, is it not? I am very tired and very hungry. If your servants have not all gone to bed, may I have some supper, please, and a glass of wine? Anything will do!"

I secretly pinched myself and then rang the bell. I had not fallen to sleep over my pipe and final whisky and Apollinaris. This remarkable and mysterious invasion of my solitude was an undoubted fact. By the time Groves appeared my visitor had removed her hat and was contemplating the arrangement of her hair in the mirror. Groves, who was a model servant, gave a momentary start of surprise and then looked steadily into vacancy. He received my confused orders in eloquent but respectful silence.

"Some supper, Groves—for one. Anything cold, and some wine!"

He disappeared. My companion succeeded in the replacement of a refractory curl, and with a parting glance at the mirror resumed her seat. I rose to my feet and began to collect my scattered wits.

"Do I understand," I began, "that you bring me a message from my brother?"

She shook her head.

"I have met your brother," she said, "but I have never yet spoken with him. He certainly does not know me or who I am."

I opened my lips to ask her bluntly what had brought her to my rooms at such an hour, but the words remained unspoken. Now that her hat was removed I was suddenly conscious that she was an exceedingly pretty woman. She lounged in my most comfortable chair perfectly at her ease, a charming smile upon her lips, her dark eyes meeting mine frankly and lit with a distinct gleam of humour. She was becomingly dressed, and although the dust of travel was upon her shoes and clothes, the details and finish of her toilette were sufficiently piquant to indicate her nationality. She was distinctly a very attractive woman. I felt my annoyance at her unexpected appearance decrease as my curiosity concerning her grew.

"Did I understand," I began, after a few moments' silence," that you had come from Marianburg to see me?"

She laughed outright, and showed a set of perfectly white teeth. It was a dazzling smile, and the teeth were magnificent.

"Not altogether, Milord Cravon. I have come on a matter of very great importance, though, and you are concerned in it."

I signified my interest and my desire to hear more. She seemed in no hurry, however, to complete her explanation.

"I am so hungry!" she remarked, with pathetic irrelevance.

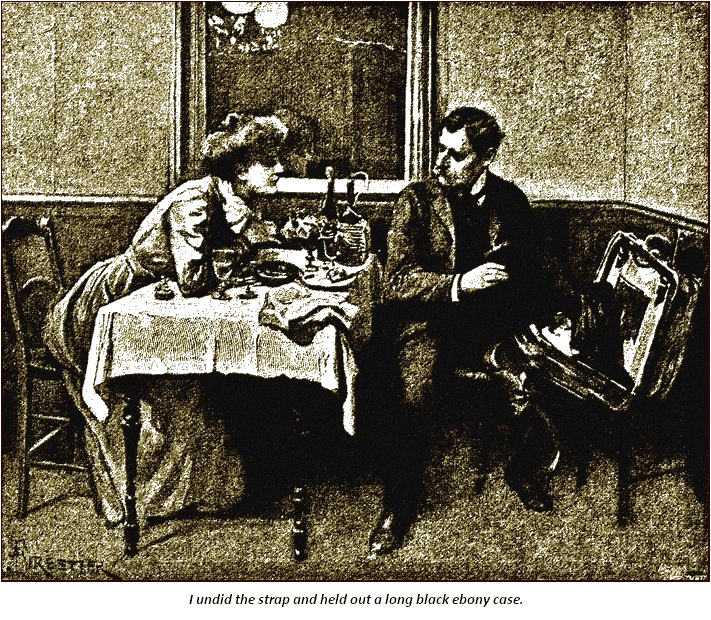

I moved to the bell, but at that moment Groves re-entered, bearing a small table. He silently but deftly arranged some cold things upon the sideboard and produced wine and a corkscrew. "You need not wait, Groves," I said, avoiding his eyes. "Bring in some coffee when I ring." He left the room and I proceeded to the sideboard.

"What may I give you?" I asked. "There is some collared stuff, cold salmon, and galantine."

"I will see," she answered, rising and coming to my side, "which looks the nicest!"

She made a selection, and was kind enough to express her approval of the result.

"Champagne or claret?" I asked.

"Champagne, if you please—one glass! Thank you. Now sit down and go on smoking, and I will talk to you."

I obeyed her. She was obviously a young woman who was used to having her own way, and it seemed to be the easiest thing to do.

"In the first place," she remarked, with something which sounded like a sigh, "who am I? It is what you want to know, eh? I would very much rather not tell you, Milord Cravon; for when you know, perhaps you will be sorry that you have been kind to me! Hélas!"

I moved in my chair uncomfortably, and murmured an insane desire that she would not needlessly distress herself by unnecessary revelations. She brushed my words aside. She was forced to declare herself.

"I am," she said, "a spy!"

"A what?" I cried.

"A spy! You understand—a creature of the police. It is you English, is it not, who detest so much the detective, who do not recognize the art of espionage?"

"By no means," I answered. "On the contrary, undertaken for the right motives and by the right class of man or woman, it is a magnificent profession, or, rather, I should call it a science!"

"You are right," she cried fervently, "Milord Cravon! You are charming! You are the most intelligent Englishman I have ever met!"

I bowed and waved my hand.

"It is a profession," I continued, "which as yet is "only in its infancy. It demands ingenuity, invention and originality. To succeed in it one must be an artist. The lights and shadows of human nature must become a close and constant study."

"Milord Cravon," she cried, lifting a glass of champagne in her hand, "you are adorable!"

"The prejudices you spoke of," I continued, "are natural! As yet it is a profession which has been adopted only by persons of inferior calibre! It should be lifted to a place amongst the fine arts. I drink, Mademoiselle, to your calling with all respect and much enthusiasm!"

She leaned over and clinked the edge of her glass against my tumbler. Her eyes were very bright and her smile was bewitching. She was, I decided, the prettiest woman I had ever seen in my life!

"Milord Cravon," she murmured softly, "you are the most delightful man in the world!"

"And now," I remarked, "suppose you tell me in what I am to have the honour of serving you."

She shrugged her shoulders.

"You have not heard, "she asked, "from your brother Reginald?"

"Not for more than a week," I answered. "Is anything wrong with him?"

She glanced at the clock.

"In a few minutes," she said, "he will be here!" I looked up, startled.

"What, here in England!" I exclaimed; " Reggie?"

She nodded.

"Yes. He is in trouble!"

"In trouble! Of what sort?"

"He will tell you himself. It will be better so."

I rose to my feet, worried and anxious.

"You say that Reggie is in trouble, is coming here!" I said. "You are in the service of the police of Marianburg. Does that mean that you have followed him?"

She shook her head.

"No. The police of Marianburg are on his side. I am here as an ally, I am here to help him. You too, Milord Cravon, must help, for it is great trouble into which Mr. Reginald has fallen!"

A smothered groan from behind her startled us both. The cigarette which I had just lit dropped from my fingers and lay smoking upon the floor. A minute before I could have sworn that we were alone in the room, but at some time or other during our conversation the man who stood before us must have made his noiseless entrance. No wonder that we were taken by surprise! Only two of the electric lights were burning, and the room was full of shadows. Standing amongst them, with his fiercely bright eyes fixed upon us, was a young man whose features, in those first few moments of half-alarmed surprise, were only vaguely familiar to me. His face was the face of a boy, smooth and beardless, but its intense pallor and the black lines underneath his bloodshot eyes had transfigured him. His evening clothes were all awry, his white tie had slipped up behind his ear, the flower in his coat was crushed into a shapeless pulp, his shirt was crumpled and his clothes were splashed with mud. He stood a grim, dramatic figure, only a few yards away from our touch, glaring at us like a wild animal face to face with its captors.

The clock on the mantelpiece ticked for thirty seconds or more, and still my lips were sealed. For years people had told that my brother, Reggie Lessingham, was one of the smartest and most debonair young men in Europe. Was it any wonder that recognition dawned but slowly upon me?

My companion was naturally the first to recover herself. Indeed, after her little exclamation of dismay at his sudden appearance, she seemed to treat Reggie's presence as a matter of course. But for my part it was a terrible shock to me.

"Reggie!" I cried. "What—what in the name of all that's horrible is the matter, boy? Are you ill?"

He tottered rather than walked towards us, and stood still, with shaking hands resting upon the little table where my mysterious guest had been supping. He looked first at her and then at me, but when he opened his mouth to speak no words came—only a harsh, dry rattle from the back of his throat. He was like a man whom torture had driven to the furthermost bounds of insanity.

I caught up a tumbler, and filling it with champagne, forced some between his lips. He drank it with a little gasp. I helped him into a chair, and drew it up to the fire. He was still shaking all over, but his appearance was more natural.

"Come! You look a different man now," I said quietly. "What's wrong? Tell me all about it. I thought that you were in Marianburg. Are you home on leave?"

He did not answer. He looked from the girl to me, and then into the fire. It seemed as though he had lost the power of speech. I gripped him by the shoulder.

"Have you been drinking, Reggie?" I cried. "Come, pull yourself together. Remember, I have heard nothing as yet."

Still there was no answer. The burning light faded out from his bloodshot eyes. He sank back wearily in his chair—he was utterly exhausted by excitement and intense nervous strain. My visitor came softly over to my side.

"Make him tell you," she whispered. "There is no time to be lost. He can tell you what has happened better than I can."

I rested my hand upon his shoulder and spoke firmly.

"Reggie, old chap, "I said, "make a clean breast of it. Let me know the worst. Is anything wrong at headquarters—a row with the chief, eh? I shall stand by you; you can rely upon that. Come! out with it!"

Reggie looked up at us with white face and trembling lips. He was in a terrible state.

"Close the door, Maurice," he faltered.

I obeyed him. He followed me with his eyes, and then looked searchingly round the room. I began to fear that the boy's brain had given way.

"You are Marie Lichenstein?" he said suddenly, addressing my guest.

She nodded.

"Yes. I know all about it. You can speak before me."

"You were at Cologne?"

She nodded.

"I am more used to rapid travelling than you," she remarked. "I came from Ostend, and saved two hours."

"You have heard nothing from Marianburg?"

"Nothing. I was to come here and wait for instructions."

Reggie was silent for a moment. When he spoke again, it was to me he turned.

"Maurice," he faltered, "something hideous has happened to me. You will help me! For God's sake don't say no!"

"Of course I will help you," I answered readily; "only I must know what it is all about. Tell me the whole story."

He shivered.

"The whole story! No, I can't do that now."

"Something has happened at headquarters?" I suggested.

"Yes. I have been robbed! There was a burglary at the Embassy, and I was robbed of some papers."

A light began to break in upon me. After all, nothing so terribly tragic had happened. Reggie had probably been indiscreet. A few words to the Foreign Secretary would set matters right.

"State papers, I suppose?"

He shook his head with a groan.

"Worse! Much worse!"

The light faded away. I was more puzzled than ever.

"Worse than State papers?" I repeated vaguely.

"Yes!"

He looked at the door again and all round the room. His voice sank to a whisper. He took hold of my hand, and drew me down so that my head nearly touched his. I could feel his finger-nails burning in my flesh.

"Swear, Maurice—ay, and you too, Marie Lichenstein—upon your honour, upon your sacred honour, that what I am going to tell you shall never pass your lips—that you will lock it deep down in your memories! Swear!"

"I swear, Reggie!"

Marie Lichenstein inclined her head.

"To me," she said, "these things are holy. It is my profession. Besides, I already know what you are going to say."

His voice sank to a husky whisper! His eyes were afire!

"They were the letters of a woman—whom I loved—who loved me!"

"A woman!" I exclaimed. "Letters! Why, Reggie!"

The relief in my tone seemed to irritate him. He held out his hand.

"You do not understand. Those letters were mine. They have been stolen from me. It is a plot of her enemies. They were written by a woman who loved me. They were written impetuously, without prudence, signed with her name. I told her —that they were destroyed! I lied, for I kept some of them. I could not bear to part with all. They were precious to me. If I do not get them back at once, I shall shoot myself. I have sworn it! But God help her! God help her!"

"Have you any clue, any idea where they are?" I asked. "You have come to England. Do you think that they have been brought here?"

"She has enemies," he muttered, "enemies everywhere, and powerful. My servant must have been in their pay. He has absconded, and he has come to England. He had only a few hours' start, but I cannot find him!"

"What, Shalders?" I asked. "Surely you cannot suspect him!"

"Suspect!" Reggie beat upon the floor with his heel. "It is no matter for suspicions. It is he who robbed the safe. He is in England somewhere. I must find him! We should have caught him on the boat."

"Are they very bad, these letters?" I asked, "or were they only indiscreet?"

"They are absolutely fatal," he gasped. "But it is not that they are so bad; it is—who she is!"

We were all silent. Reggie's face was ashen. The girl was watching him curiously.

"If I am to be of any use to you, Reggie," I said, "I must know her name, I must know all the circumstances."

He half rose from his chair, clutching at the arms. His voice was hysterical.

"It is a little packet!" he cried with a sob. "There are only four letters and a ring, but with them goes—the honour of a queen!"

At first I had but one thought—Reggie was mad! But when I looked from his white, anguish stricken face to my other visitor, I saw that she, at least, did not think so. Apparently she was not surprised. Reggie's bitter cry had only told her what she already knew. Then, whilst I stood there wondering, a sudden memory rose up before me. I thought of a long visit of my brother's years ago to the capital where he was now attache, and of certain half-jesting allusions to the beauty of a certain princess, which Reggie had taken very ill indeed. There had been a paragraph in a so-called Society paper, scandalous but vague; somebody had shown it to him, and Reggie's language had been awful to listen to. These things came back to me in those few tragical moments, and dimly suggested others. For years we in England had seen very little of Reggie. His leave was mostly spent at the capital to which he had taken special care to be appointed at his entry into diplomatic life. With contemporary history I was sufficiently well acquainted to know that the princess had become a queen. Conviction came to me with a sudden, lightning like rush. He had spoken the truth! I felt the perspiration stand out in beads upon my forehead as I recognized his terrible dilemma.

"Reggie," I said, "I want the whole story, please. If I am to be of any use to you, I must hear it all. Out with it!"

He hesitated, with his eyes fixed upon the girl. She shrugged her shoulders.

"You do not mistrust me, Monsieur Lessingham?" she exclaimed.

He hesitated.

"I do not mistrust you," he said, "but—"

She stopped him with a little gesture.

"Ah, well!" she exclaimed, "I do not wish that you should have any further anxiety. Look, if you will, upon my credentials."

She drew a folded sheet of paper from her bosom and laid it upon the table. The words were so few and written so boldly that I too could see them?

"Trust Marie Lichenstein.—Fedora."

With a sudden movement Reggie lifted the piece of paper to his lips. Then he laid it reverently down.

"You recognize the handwriting?" she asked.

"It is enough," he answered. "You shall hear in a few words all that there is to tell. It is the story of a simple robbery. A packet of letters and a ring have been stolen in a most wonderful way from my room in the Embassy. They were kept"

I held up my hand.

"Reggie, forgive me, but I must know! Were they written before her marriage or after?"

"All—save one—before. I have had letters since—a few—on my promise that I would destroy them as they came. I kept that promise faithfully —until last week. Then I was horribly tempted! I could not see her for several days. A letter came! Oh, I was foolish, but the letter meant so much to me!" he groaned. "I kept it for an hour or two, meaning to destroy it at night. It was stolen with the others!"

"That letter "I began, looking searchingly at Reggie.

"It was—at least—imprudent!" he moaned. "To those who do not know her, as I know her, it will seem worse!"

I turned towards the girl. Had she anything to say? For my part, the matter seemed already hopeless. I could see no ray of light anywhere.

"Will you tell us, please," she said, "all about the actual robbery?"

"You have had particulars," he said. "You know all that there is to be known."

"It is true," she admitted; " nevertheless, your brother does not, and I myself would like to hear the story from your own lips."

He rested his head wearily upon his hand; he had taken a chair now, and began with his eyes fixed upon the fire.

"I kept the packet in a safe let into the wall of my room, and fastened with a combination cipher and Bramah key, exactly the same as the chief has for the treaty safe. The letter I speak about I received by hand on Sunday morning. I had it with me all day. At eight o'clock I went out to dine. I left the letter with the other packet in my safe. The key never leaves my person. I have a hollow gold band around my arm, and the key fits into it. When I returned at night everything was as usual. I opened the safe, meaning to read the letter over and then destroy it. It was gone and with it the packet and a ring. I rang my bell. There was no answer. I rushed along the passage of the Embassy shouting for Shalders. He was my servant. No one knew anything about him. I behaved, I am afraid, like a maniac. I should have been cool, but I was not. I could not contain myself. At last I heard news. He had been seen to leave the house about an hour after me, carrying a bag. I traced him to the station; he had taken a ticket to London. I followed him."

"The key?" I asked.

He touched his arm.

"It is here still. It has not left my possession for a second."

"How do you suppose, then, that the safe was opened?"

Reggie groaned.

"God alone knows! All I can say is, that it was done with a key, and the only other one made has never been out of the chief's possession, or, at any rate, out of the secretary's room. Sir Henry assured me of that himself. How the cipher could have been adjusted, and the safe opened Oh, Maurice!" he cried wearily, "it makes my brain whirl to think of it!"

He dropped his head wearily into his hands and leaned upon the table. At that moment there was a knock at the door. Groves came softly into the little circle of light with a telegram upon his salver. He brought it to me. It was addressed to "Miss Lichenstein, c/o the Earl of Cravon."

"I thought that it might be for the young lady," Groves murmured.

I handed it to her. She studied it for a few moments in silence. Then she took her gloves from the table.

"Will you allow your servant to call for me a hansom cab?" she asked. "I must go."

"Is there any news?" Reggie asked, suddenly looking up with white face.

She shook her head.

"Not yet. These are my instructions; I must obey them at once. Monsieur Reginald, do not despair! I shall do my best. Milord Cravon, au revoir! It has been a very leetle visit, but—oh! so pleasant!"

Her dark eyes flashed sweetly at me, and she took her leave with a bewitching smile and backward glance over her shoulder. I heard Groves whistle for a hansom, and she drove rapidly away. Then I went back to Reggie. He was leaning forward across the table, and was breathing heavily. I bent over him quietly. He had fallen asleep. In the morning I was even more shocked to see the alteration in my brother. His clothes hung loosely about him, as though he were just recovering from a long illness; his cheeks were haggard, and his eyes deep-set and unnaturally bright. He held a telegram in his hand when I entered the room.

"Any news?" I asked.

He shook his head.

"None," he answered mournfully. "My message simply says, 'Situation unchanged.'"

I rang the bell for breakfast. Until he had eaten something I would not let him speak. Afterwards I pushed two easy chairs to the fire, and passed him a pipe and some tobacco.

"I am going to ask you some questions, Reggie," I said.

"Yes. Go on," he answered feverishly.

"How long has Shalders been with you?"

"For six years. Ever since I had a man."

"Has he been a good servant?"

"I would have trusted him," Reggie said, "with my life."

"Where are your rooms in the Embassy?"

"On the third floor."

"Anybody else near you?"

"Sir Henry's private secretaries—Dick Colquhoun and a fellow named Harris."

Dick was an old school fellow. I passed him by without a thought.

"Harris, "I repeated thoughtfully. "Is he by any chance a connection of the Foreign Secretary's?"

Reggie nodded.

"Nephew."

"Are you on friendly terms with him?"

"Not particularly. He is not a sociable fellow. He was away on a week's leave, shooting somewhere."

"When was he expected back?" I asked. "The day I left."

"There was no one else who had rooms upon the third floor?"

"No one."

"Had you any difficulty in hearing about Shalders at the Marianburg railway station?"

"No."

"He did not seem to take any particular pains about concealing his identity?"

"None at all. I traced him as far as Paris easily. He took a sleeping berth in his own name."

"He travelled first-class, then?"

"Yes."

"And at Paris?"

"I lost him. I was only one train behind, and I believe that I reached London first."

"You think that he stayed over in Paris?"

"Yes."

"He took his ticket for London?"

"Yes."

"You have had no recent unpleasantness with Shalders? Your behaviour has been such that he would presumably consider you a good master?"

"I am sure of it."

"Then what possible motive, Reggie, could he have had in stealing those letters?"

"You might as well ask me," Reggie cried in despair," how he could possibly have opened the safe. All I know is that he has bolted and the letters are gone."

"Can you think of any one," I asked, "to whom those letters would have been specially valuable?"

"No one—except an enemy."

"And has she an enemy that you or she knows of?"

"Not one."

"Then we must conclude that they have been stolen for blackmail."

"I suppose so."

"And this is utterly unlike anything you would ever have expected from Shalders?"

"Utterly."

"Have you seen her since, Reggie?"

He covered his face with his hands.

"For one moment—one horrible moment!"

"You have warned her?"

"Yes."

"Is she taking any steps?"

"She has interest with the secret police. They are following Shalders. Marie Lichenstein is their agent."

"Can you communicate with her, or some one absolutely trustworthy in Marianburg?" I asked.

"Yes. I have had two or three telegrams already."

"Any news?"

"None."

"Sit down and write out a telegram."

He obeyed without a word. I placed pen and ink and forms before him.

"Say, 'Is Harris at Embassy?'"

"Harris, "he repeated. "What has he to do with it?"

"Never mind, Reggie. You send the telegram. An affair like this is mostly guess-work. There is no harm in asking the question, anyhow."

Reggie thought for a moment, turned it into cipher and wrote it slowly out.

"Now go and despatch that yourself," I said. "The walk will do you good."

He rose wearily.

"I don't see any object in sending this, "he said. "It is ridiculous to think of Harris in connection with the affair. He wasn't even there. Shalders took the letters! There is no doubt about that. What we want to do," he concluded, with a feverish little burst, "is to find Shalders."

"Send it any way," I answered. "Promise that you will send it."

He nodded listlessly.

"Oh yes, I'll send it," he said. "I've told you that it's no good, that's all."

"Do you know if Shalders has any friends in London?" I asked.

"He told me once that he had a brother, a hall-porter at the Geranium Club."

"Why not go on there and see if he has heard anything of him? You might find out his other relations, and they could be all watched."

"There is more sense in that," he muttered. "At least, it will be something to do!"

He left the room. I spent the morning reading a file of The Times for the last six months. Gradually I became more and more interested. I began to see the glimmerings of a clue. I was interrupted only a few minutes before luncheon-time by Groves announcing a visitor.

I looked up from my papers.

"Who is it?" I asked impatiently.

"A gentleman, my lord," Groves announced. "He declines to give his name, but he has a large box and a note which he says that he must give into your own hands."

"Show him in," I directed.

A man was ushered in, tall and by no means ill-looking, with a thin black moustache, steel-grey eyes and somewhat foreign appearance. He was carefully, in fact, irreproachably, dressed, with a single exception—he wore a brilliantly red tie, which seemed a little out of place with the rest of his toilet.

He bowed and regarded me keenly.

"The Earl of Cravon, I believe?"

I admitted the fact. He produced a note and handed it to me without further speech. It was addressed to me in a delicate, feminine handwriting, and a faint, familiar perfume assailed me directly I touched the seal. It was undated and the notepaper was quite plain.

My dear Friend,—

Necessity, or rather your brother's necessity, compels me to ask what will seem strange to you. Yet do as I send you word, and later I will explain. The bearer of this has a box. Let it be placed in an empty bedroom of your house, unknown, if it be possible, to any save your own confidential servant. Further, send me by him a latch-key of your house, and do not you yourself retire for the night until you see or hear from me. You will think that I am asking you strange things. No matter. All that I can I will explain to you very soon; and for the rest— well, it is for your brother, you know. Is it not?

Do not hesitate to do exactly what I ask. Very much depends upon it. As yet I cannot send you any news, but very soon our effort will be made, and you will know with what success.

Farewell, Milord Cravon. It is for a very short time.

Marie.

I looked from the note to the messenger.

"Where is—Miss Lichenstein?" I asked.

He spread out his hands.

"I cannot tell you, sir," he said. "It is better for you not to know. Will you give me the key? The box of which she has made mention is in your hall."

I went out and looked at it. It was an ordinary lady's dress-basket. Groves was examining it from a little distance, with his hands behind his back and a curious expression upon his face.

"Have this box taken into the guest-chamber upon the first floor, Groves," I directed. He bowed and hurried away. I returned to the library.

"Here is the key," I said to the man who awaited me, taking my own latch-key from my watch-chain

"I will do what Miss Lichenstein has asked."

He accepted it with a bow.

"You will not regret it," he answered quietly. "By this time to-morrow I trust that we may report ourselves successful."

"You are from Marianburg?" I asked.

He took up his hat.

"I see no reason for concealing the fact, Lord Cravon, that I am of the Marianburg secret police. This affair has been placed wholly in my hands. You will forgive me now if I hurry away."

I watched him step from the pavement into a small, handsome brougham and drive rapidly away. Then I hastened to change my own clothes and order a carriage.

I drove first to the house of Sir Charles Wimpole, a somewhat intimate friend of mine, who had a seat in the House of Commons and held a minor post in the Foreign Office. I found Wimpole Lodge, however, in the hands of the whitewashers and decorators. Sir Charles, I was told, was staying for a week or so at the Hotel Maurice. A few minutes later I drove into the splendid courtyard of the hotel and made inquiries at the bureau.

Sir Charles, I was told, had gone out only a few minutes before, but he was expected back in a quarter of an hour. I lit a cigarette and subsided into one of the luxurious lounges in the hall. I wanted particularly some information which Sir Charles would be able to give me, so I decided to wait.

I had been there scarcely a minute when the rustling of a dress across the marble floor induced me to raise my eyes from the paper which I had picked up. To my amazement, it was Marie Lichenstein. She was charmingly dressed in a Parisian toilette of red and black, and a poodle, shaved in the latest fashion and wearing a jewelled collar, trotted behind her. I rose to my feet, hat in hand, and stepped forward. To my blank astonishment, she met my eyes with a stony stare of non-recognition. I muttered her name—she turned coldly away.

"Monsieur has mistaken me," she said. "I have not the honour of his acquaintance."

She retreated to the further end of the hall and sat down in an easy chair, with the dog by her side. I resumed my seat, and looked sharply round to see if any one had witnessed my discomfiture. I fancied that the head-porter, who had suddenly averted his head, was indulging in a faint smile; I was sure that a man, whom I had not previously noticed, and who was sitting in a dark corner by the cigar stall, was laughing softly to himself. I looked at him more closely. Something about the man's mouth seemed familiar. I leaned forward and saw him distinctly. It was the messenger whom Marie Lichenstein had sent to me scarcely an hour ago.

I threw my cigarette away and walked down to the cigar stall. I made some trifling purchases, glancing every now and then at the man, who was barely a couple of yards away. He neither avoided my notice nor courted it, but there was not the faintest gleam of recognition in his face. I purposely tendered a banknote to the girl in charge of the cigar stall. She left to get change, and I spoke softly to the man.

"We meet again very soon," I remarked.

He looked up at me with a bland but unintelligent smile.

"Monsieur is, I think, mistaken," he said. "I have not the pleasure of his acquaintance."

I muttered something which was scarcely polite, and returned to my seat. I felt that I was being drawn into some sort of a conspiracy. The man and the woman sat at opposite corners of the hall, and not even a glance passed between them. They did not know one another—they did not know me. Both had assumed with perfect naturalness the listless attitude of people passing away an hour of boredom. All the same I began to realize that they were waiting for some one. Every time the swing-doors were opened by the hall-porter, who stood like a machine at his post, the man looked up. There was no anxiety or nervousness in that slight, sidelong glance. It was to all appearance nothing more than the ordinary curiosity of the casual hotel-lounger. Only I, who was watching very closely indeed, could see every now and then faint signs of impatience underneath his insouciance.

I lit a fresh cigarette and waited. They were watching for some one! Was that some one the man who had planned and carried out this strange robbery?

I too began to scrutinize the little stream of people who were passing in and out. So far as I could see, they were the usual cosmopolitan throng who patronize such hotels as the Maurice. The majority were Americans, plainly dressed and carrying satchels with an occasional Baedeker. Every now and then a Frenchwoman, like a brilliant butterfly, came flitting in, and the gay chatter of voices, introductions and leave-takings filled the air. It was just when the hall seemed fullest that the door swung back and a man entered with a rug upon his arm, followed by one of the outside porters carrying a portmanteau. I glanced over at the face of the watcher by the cigar stall, and felt a sudden thrill of excitement. A look had flashed across from the man to the woman, and I intercepted it. I knew at once what it meant— this was the man!

The new-comer passed within a few feet of me, and I was able to observe him closely. He appeared to be from thirty to thirty-five years old, he was of medium height, sallow and thin. He was dressed in a blue serge suit of foreign cut, and he wore a black bowler-hat, which would have been the better for a good brushing. As he passed from the door to the hotel office, he looked quickly and furtively around at the loungers in the hall, and seemed relieved to recognize no familiar face.

He disappeared into the bureau, and almost immediately afterwards Marie Lichenstein rose from her corner and came quietly down the hall until she reached the space between the bureau and the lifts. She paused here and exchanged a few words with one of the hotel pages. As she dismissed the boy, the new-comer issued from the hotel office, and raising her eyes, they fell, as if by accident, upon him.

I know what I should have felt if a woman as beautiful as Marie Lichenstein had looked at me in like manner. She must have been a consummate actress. At first her glance denoted nothing but curiosity, in a second or two it had softened into interest, then she passed on with a faint, but bewitching, smile at the corners of her lips. The newcomer hesitated awkwardly for a moment. Then he handed his rug to the porter who was carrying his bag.

"You can take them into my room," I heard him say. "I shall be there in a few minutes."

The servant withdrew; the new-comer glanced after Marie Lichenstein. She had swung down the hall with slow graceful movements, and was looking idly into the restaurant. The man followed her as far as the cigar stall, where he made some trifling purchase. As he stood there the woman passed slowly back again. He turned and looked at her more boldly. This time her eyes fell quickly before his, but that wonderful smile quivered once more upon her lips. She walked on towards the lift and entered—the man followed her. It seemed to me that as they swung up out of sight I saw him bend down towards her!

When they had gone I drew a little breath and glanced down towards my fellow-watcher. He was lighting a cigarette and smiling softly to himself. In a few moments he rose and, drawing on his gloves, passed out of the hotel. I heard the whistle which summoned a private carriage and the sound of wheels driving away. It had all happened so quickly that it was hard to realize anything. Only I looked at the two empty seats, and I think I understood that the curtain had rung up upon the first act of the little drama of which I had unwittingly become the sole audience.

In a moment or two I rose and entered the office. I had intended to take a room, in order to see for myself under what name this latest comer to the hotel had registered. But as it happened this was not necessary. The office was crowded, and the visitors' book lay open before me. The last name was written boldly enough—the ink, indeed, was not yet dry. I read it over slowly to myself. It was quite unfamiliar:—

Maxime De Carteret,

Buda Pesth.

No. 357.

I turned away and came face to face with Wimpole. He greeted me with some surprise.

"What are you doing here, Cravon?" he asked. "I thought you hated these huge hotels."

"I came to see you," I answered. "Are you busy, or can you spare me half an hour?"

"I'm off to the House presently," he said. "We'll have a cigarette first, if you like; and then, if you've nothing better to do, you might give me a lift down. I saw your carriage outside." We sat down on one of the lounges.

"I have come to beg for some political information, Wimpole," I said.

He looked at me with a smile.

"I'm very much flattered," he said. "Are you going to speak on the Zanzibar question, then?"

I shook my head.

"No. I'm not going to speak at all—at least, I do not want the information for political purposes. Nor has it anything to do with Zanzibar."

"China?"

"Much nearer home."

"Europe?"

I was silent for a moment.

"You remember Reggie—my younger brother?"

"Quite well," he answered. "He came to Eton the year I left, and he followed me to Magdalen. Nice boy, but I haven't seen him for years."

"He has been at Marianburg," I continued, "and I am sorry to say that he has got into a scrape there. It's a very mysterious and complicated business, but I'd give a good deal to help him out of it."

"At Marianburg!" Wimpole whistled softly to himself and began to look more interested.

"I daresay you know," he said,"that matters politically are looking very queer there just now?"

"I know nothing," I answered, "except what I have gathered from The Times. It seems to me that there is something in the background there, and I have a sort of theory that Reggie has got drawn into it."

Wimpole looked around him.

"Marianburg," he said, "is giving us just now a great deal of trouble. This is scarcely the place to talk of it, but if you will drive me down to the House we can talk as we go."

We both rose. At that moment the lift doors opposite to us were opened, and Marie Lichenstein stepped out, dressed for walking and followed by the man in the blue serge suit. She passed me with unseeing eyes and perfect unconsciousness, chatting all the while gaily to her companion. Wimpole looked after her admiringly.

"What a handsome woman, Cravon!"

I smiled. We all four stood on the steps together, and a porter, who had recognized me, called for my carriage. I saw Marie's companion turn round as though he were shot. Wimpole looked at him curiously.

"The fellow with her seemed to recognize your name," he remarked.

I nodded, but took care not to advance towards him. The hansom arrived first, and I heard their destination

"Charbonell's, Bond Street."

They drove off. I stepped into my brougham, which followed up. On the other side of the court-yard a man was strolling up and down. It was the messenger whom Marie had sent to me—the man with the red tie.

*****

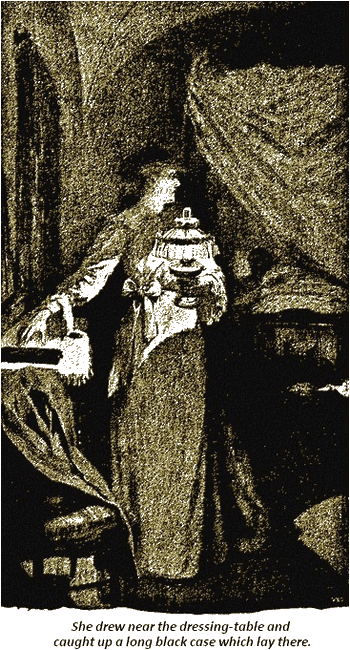

There followed for me an evening of inaction during which I thought a good deal and smoked too much. Reggie had not returned, nor was there any message from him. About eight o'clock a telegram arrived from Marianburg, but, although I opened it without hesitation and with considerable interest, it was in cipher and unintelligible to me. After that the hours passed away very slowly. At twelve o'clock I fell asleep; at one I awoke with a sudden start and a chill consciousness that I was not alone. I sat up in my chair. At first I thought that I must still be dreaming. The woman who stood before me with uplifted and warning finger was dressed in the fashion of another age. Her hair and cheeks were powdered, diamonds flashed from her shoe buckles, her corsage, from the velvet which bound her hair. Her dress of green satin was strangely cut and looped up on one side to display a gorgeous petticoat. She held a fan in her left hand, and her fingers were ablaze with rings.

"Milord Cravon!" she whispered.

I knew her then, as indeed I might have done from the first, for her eyes and mouth were eloquent enough and her face was not one to be easily disguised.

"Marie Lichenstein!" I cried. "Why—"

She interrupted me.

"I have been to your Covent Garden Ball," she said. "Give me some wine quickly."

I had some at hand and poured her out a glass. The hand which took it from me was shaking like an aspen leaf. I looked at her more closely, and I saw that she was a sorry masquerader. There was a pallor upon her cheeks more real than the delicate blanching of the powder, and a fear in her eyes which was like the fear of death. Behind her, across a chair, had fallen a black opera cloak and a domino. She stood there in her brilliant dress a strange, wan picture.

I gave her more wine. She drank it eagerly and sank down in my easy chair. I took her hand and held it in mine. It was as cold as ice.

"I am afraid," she murmured, "that I am losing my nerve. Yet I never thought that it would end like this."

"Something—has happened?"

"A great deal has happened," she declared, "much that I would were undone. Milord Cravon, we have failed!"

My heart sank. Yet from the moment when I had recognized her I had felt sure of it. She was like a woman wholly unnerved by a great shock, and with it all I knew that she was not a woman to be lightly brought into such a state.

"He was—not the man then?"

"Of that I am not sure," she answered; "but it is very certain that he has not the letters. If he is the man who stole them, and of that Meyer is certain, then he has already made his bargain and parted with them. We were too late. We have run a great risk for no purpose"

"I am sorry—for your sake as well as Reggie's," I murmured.

"My friend," she said, looking at me with eyes which seemed suddenly very dim and soft, "by this time to-morrow you will not be sorry for me any longer! At the sound of my name you will shudder, at the thought of me you will shrink as one shrinks from a poisonous thing! But after all—what matters?" she added, with a hysterical little laugh. "I have but one thing to think of now, and that is to get away. Milord Cravon, have you servants whom you can trust?"

"Implicitly," I assured her.

"I need a carriage," she said.

"My night cab is ready," I answered. "I have only to touch a bell. The horse is already harnessed"

"And my box?"

I motioned her to follow me, and showed her the room where it had been placed.

"The cab—in five minutes," she said, as I turned to go; "I shall not be longer."

She kept her word literally. I was prepared for some sort of transformation, but scarcely for anything so complete. She glided into my study before the five minutes were up, a slim, sad figure in the sorrowful garb of a sister of mercy. From the rough, black gown which fell upon her ill-shaped shoes to the gold chain about her neck, the metamorphosis was absolute and complete. I gasped for breath as I looked at her.

"I have left you but one thing to do, Milord Cravon," she said. "The opera cloak and domino there—will you put them in the box which I have left upstairs? Keep that box in a safe place until you have an opportunity of destroying it, and every trace of Marie Lichenstein has vanished."

"But—where are you going?" I cried.

"To a convent at Highgate. I have letters from a sister at Brussels. When your door closes behind me, I am as safe as though. I were a thousand miles away. Everything has been perfectly arranged, and I am expected to-night. Is the carriage here?"

"It is waiting," I answered. "Do you mean, then, that we shall not meet again?"

She sighed.

"It is a small world," she said softly.

"And Highgate," I suggested, "is a small suburb."

She shook her head.

"Not there," she said decidedly. "Whatever you do, do not come there, or make any inquiries. You promise?"

"Faithfully."

She sighed once more. I found myself holding her hand. Her dark eyes looked sorrowfully into mine.

"After all," she said, "it is true what I have told you. By this time to-morrow you will loathe me. If my hand lay within yours—as now—you would cast it away."

"I can assure you," I said earnestly, and raising it a little towards my lips, "that I should do nothing of the sort. I should do precisely what I am going to do now."

The little white fingers were as cold as ice. She drew them gently away and I walked with her to the door. With my hand upon the latch I paused. There was something I wanted to say to her, but she gave me no opportunity. With a sudden impulsive movement, she threw the door open herself, ran down the steps and vanished into the carriage. She did not look round nor say a word of farewell, but as she crossed the pavement I heard something which sounded like a sob break from her lips.

It was on my plate when I came down to breakfast. I saw it there when I entered the room, neatly cut and folded, by the side of a little pile of letters. How I hated the sight of it, hated the thought of touching, of opening it! The Morning Post is not a paper given over to sensationalism. I knew that whatever had occurred would be temperately and truthfully chronicled; yet none the less I shrank with positive dread from opening those innocent pages. Nor were my apprehensions ill founded. When at last I summoned up courage to take the paper into my hands, my worst fears were instantly confirmed. At the head of a column, in thick black type, it stared me in the face:—

TERRIBLE MURDER AT THE HOTEL MAURICE!

For a moment I was incapable of reading. I was dizzy and everything swam before my eyes. Then I pulled myself together. I gripped the paper with both hands and read with fierce eagerness every line.

"Early this morning the body of a gentleman, a visitor

at the Hotel Maurice, was discovered in his room under circumstances which

leave little room for doubt as to the manner of his death. We are at present

without full particulars of the tragedy, but such information as we have

makes it perfectly clear that a brutal murder has been committed. The

deceased was found stabbed to the heart with a long, thin dagger of foreign

make. He had only arrived at the hotel during the afternoon, and had

registered under the name of Maxime De Carteret.

"Later. Further particulars are to hand with reference to the murder early this morning at the Hotel Maurice. The deceased was seen talking during the afternoon to a lady visitor at the hotel, who had herself only just arrived, and who had registered under the name of Lichenstein. The two were apparently on the most cordial terms and dined together in the restaurant, and subsequently left the hotel together for the Covent Garden Ball. They returned quite early, and went up in the lift to their respective rooms, which were in the same wing and on the same floor of the hotel. They were accompanied by a third person, who had also arrived during the day, and registered under the name of Jules Van Drooden, of Brussels. The three were last seen together talking on the landing outside their rooms, but about half an hour later the lady, still in her fancy dress, rang for the lift and descended to the ground floor. She asked the hall-porter to call her carriage, remarking that the gentleman with whom she had been to the ball had been taken ill, and she had been compelled to return with him, but as she had friends there, she was going back for an hour or two. She drove off, and up to the hour of going to press had not returned to the hotel. We understand also that Mr. Van Drooden, who, together with the lady, was last seen with the murdered man, has disappeared.

"On inquiry early this morning our representative

learned that, although the clothes and belongings of the deceased had

apparently been searched through, his money, jewellery and papers were

untouched. On reference to the latter, it has been ascertained that his real

name is Shalders, and that he was a valet in the service of the Hon. Reginald

Lessingham, who is attached to the Embassy at Marianburg."

The paper slipped from my fingers. It was as bad as—even worse than I had feared. It was a horrible and unpardonable deed; not only that, but it was an ineffective one. If he had ever had the letters, he must have parted with them. Whatever his motive for the robbery might have been, he had met with a terrible retribution.

The door opened and Reggie walked in, followed by a servant with the breakfast. In the clearer daylight I was shocked to see how great a change the anxiety of the last few days had wrought in him. His eyes were set in deep hollows, his cheeks were thin and haggard. However it all might end, he would carry the marks of agony with him to the grave.

"Reggie," I said, "there is something here which I want you to read."

He held out his hand. I gave him the paper.

"Read it carefully," I said, "and tell me what you think of it."

He devoured it with a sort of fierce joy, mingled with amazement. His eyes glittered with an unnatural light. I saw that I must keep him going as much as possible. Action of some sort was absolutely necessary for him. He was on the verge of madness.

"Very good! very good!" he exclaimed. "It is the man who robbed me whom they have killed. Very good! It is magnificent! Dead, is he? I am glad!"

"You must remember, Reggie," I said, "that this may be a very just retribution, but it scarcely looks as though it were going to help you. Let me tell you this. I have seen Marie Lichenstein since. He had not the letters. It seems as though he had parted with them."

"Vengeance is something," Reggie muttered; but he was white once more to the lips and his voice faltered.

"There were two telegrams for you," I remarked with a sudden thought. "Have you had them?"

"No! Give them to me!" he cried.

I fetched them myself from the library. He tore them open. As he read his expression changed into one of blank bewilderment.

"Listen to this!" he cried.

"'Your servant, Shalders, discovered yesterday in the attic at Embassy, gagged and chloroformed. Was attacked in your room on Sunday evening. Cannot identify assailant. Very weak and exhausted, but will probably recover.'"

Reggie looked piteously at me, holding one hand to his forehead.

"What in God's name does it mean?" he cried.

"Open the other telegram," I answered.

He held it out.

"There is nothing in it," he declared. "It is only about Harris. He has been back, but applied for extension of leave, and left again. Damn Harris!"

"There have been wishes," I murmured softly, "whose accomplishment has been more distant."

I declined to discuss the matter further until after breakfast, although, so far as my brother was concerned, the meal was little better than a farce. He made a pretence of eating, but all the time his eyes were following me. It was pitiful to watch him.

"Reggie," I said at last, filling my pipe, "in the first place, are you completely satisfied that your telegrams from Marianburg are to be relied upon?"

"They are unimpeachable," he answered. "I would answer for their truthfulness with my life."

"In that case," I said, "this means work for you, Reggie. If Shalders is really in Marianburg, we must find out who it was who robbed you and has paid the penalty."

He sprang up at once.

"I am ready!" he cried. "What shall I do?"

"Go to the Hotel Maurice," I said, "give your card and ask to be allowed to identify your servant. If it is Shalders—well, some one from Marianburg must be sending you false information. If it is not Shalders, say nothing at all. Be very careful that you show no surprise."

Reggie went out, and I heard Groves whistle a hansom up for him. I lit a pipe and studied carefully for some time certain numbers of The Times which I had sorted out from the pile. Just as I began to see a glimmering of light, Groves drew back the curtains which divided my rooms and announced a visitor.

"It is a lady to see you, my lord," he announced. "She says that her business is urgent and important."

"Her name?" I asked.

"She says that you would not know it, but that she must see you at once. She inquired first of all if Mr. Reginald were here."

"You can show her in, Groves," I directed.

A woman swept into the room almost as I was speaking, waving my servant away with an imperious gesture. She was plainly dressed in black and closely veiled. I could only see that she was young, and that she carried herself with the ease and grace of a beautiful woman. I rose to my feet.

"You are Lord Cravon?" she said quietly. "Will you send your servant away? I wish for a few minutes' conversation with you."

I looked at Groves and he withdrew at once.

She waited until the door was closed, and then she raised her veil.

"You do not know me?" she asked.

I shook my head. She was certainly a very beautiful woman, and of a rare type. Her hair was red gold and her eyes and eyebrows dark. Her features were delicately cut, and of patrician type; she carried herself in such a manner that my rooms seemed the smaller for her presence. Suddenly a very brilliant smile parted her lips, and at the same time I realized that her face was perfectly familiar to me! Where had I seen it?

"You are not like your brother," she said.

A vague uneasiness crept over me.

"You came—to see him?"

She shook her head. Her face hardened a little.

"I do not wish to see your brother ever again in my life," she said. "He has broken a promise to me."

"You—you are not—"

She held out her hand.

"That will do," she said. "I come from Marianburg."

I bowed low, but I was overwhelmed with embarrassment and dismay.

"Your welcome is scarcely flattering," she remarked with a smile.

"Madam," I answered, "I fear that your presence is a token that the worst has happened."

"On the contrary," she answered me, "nothing has happened at all. It was the waiting for news which wearied me so. I had arranged for an incognito visit to Paris, and I came over here by the night boat. Tell me, what news have you?"

I showed her the telegrams, and I told her of Marie Lichenstein and the murder at the Hotel Maurice. She listened without emotion or interruption of any sort. When I had finished, she was silent for several minutes.

"If your brother's servant was not the thief," she said at length, "I shall be inclined to believe that this is a political plot."

"Your majesty," I answered, "should be the best judge of that. It is hard to believe that there are people who would do you a wanton injury."

"Oh, I have enemies enough, no doubt," she remarked lightly. "The pity of it is that a woman in my position is never conscious of them."

"Is there any reason," I asked respectfully, "why you should have political enemies?"

"Yes."

She seemed indisposed to say more. I glanced towards the pile of papers at my side.

"I have been trying," I said, "to understand the politics of your country."

She glanced at them with contempt.

"Tear them up," she said; "they will not help you."

"They have given me an idea," I ventured to say.

"When," she asked, with apparent irrelevance, "shall you know who this unfortunate man at the Hotel Maurice was?"

"In less than half an hour," I replied. "Reginald has gone there now."

"I shall wait to know," she said; "but I do not want to see your brother, or to have him know that I am in England."

"It would certainly be wiser," I agreed.

She shrugged her shoulders.

"It is not," she said, "a question of wisdom. Your brother is a foolish boy, and he has disobeyed me. I shall not forgive him."

"He is terribly distressed," I ventured to say.

"I am glad to hear it," she answered.

"Do not think," I continued, "that I wish to defend him; but his motive for keeping those letters was, at least, excusable."

She shrugged her shoulders, and looked at me with a smile; but there was no tenderness in her face.

"Such sentiment!" she exclaimed mockingly. "Yet, perhaps, if I cared for him still, it might mean something to me. But that is all over. He has grown too dismal, he does not amuse me. And, my friend," she continued, leaning her head upon her shapely fingers, "Marianburg is very dull. It is very respectable, but it is exceedingly dull."

"I have always understood," I murmured, "that your majesty's court was a brilliant one."

She yawned.

"If I return to Marianburg," she said, "you shall come and judge for yourself. I will introduce you to the most beautiful women in my country. To look at they are adorable, but for wit, for conversation—well, you will find them nothing but statues. My court reminds me of a wonderful automatic model I once saw. You drop a penny somewhere, behind, and little waxen figures come out and promenade, exchange stiff curtsies and wooden speeches, and bow one by one before their king and queen, whose hands go up and down with the regularity of clockwork. There are times," she continued, speaking in a lower key, "when I have prayed for something of this sort to happen. If it were not for the scandal—well, I should fear nothing."

"It is the scandal, madame," I said, "which we must prevent. My brother would break his heart if you should suffer through his weakness and indiscretion."

She raised her eyebrows and smiled at me.

"And you?"

"Madam," I answered, "I would ask for no greater happiness than to serve you."

I could not keep the admiration from my face and tone, for she was very beautiful and very gracious. She looked away with the smile still lingering upon her lips.

"I wonder," she said, "what news I am most anxious to hear? If those letters are in the hands of enemies, if they are to be given to my husband? well, I shall be a free woman."

"Your freedom," I said, "would be bought at a great price."

She looked at me earnestly.

"My friend," she said, "there is but one life; and if you believe that to be a queen is to be a happy woman, let me tell you that you are very ignorant. Let me tell you this—royalty is the nearest approach to slavery which this century permits. I have felt, oh, many and many a time, that for one hour of real life I would give the rest of my days!"

"Your majesty," I said respectfully, "the price is too great."

She bowed her head.

"What is—is," she murmured. "I shall be none the worse woman if Europe has this story thrown to her scandal-mongers. Really," she continued, with a soft laugh, "it would be amusing. There have been princesses before who have—well, become independent, but a queen—never! Imagine the sensation! The music-halls would bid record prices for me, and great managers would discover that I was a genius, and they would beg me to go on the stage. I"

"Your majesty "I protested.

She threw me a swift, sweet glance.

"My friend," she said, "forgive me. You are right. Believe me, if I ever did gain my freedom, my feet would never tread any stage, nor should I ever occupy the throne of the demi-monde. Would you like me to tell you what I should do?"

"Very much," I answered truthfully.

"I should desire," she said softly, "to disguise myself in some way, so that no one who had known me as I am to-day would recognize me in my new life. I would be perfectly free, and I would have a studio in Paris, so that I might paint when I was in the humour for it; a yacht always ready, so that I might sail when I chose; a cottage in Devonshire, that I might enjoy Nature when I was in the mood; and friends who cared enough for me to come when I summoned them, and leave when I desired it. Ah! when I dream of this, half the dread of the present vanishes."

I rose suddenly to my feet. I had heard a hansom stop at the door.

"It is my brother, madam," I exclaimed. "If you still desire not to meet him, will you come this way?"

She followed me across the hall and into my drawing-room.

"My presence, I trust, does not inconvenience you, Lord Cravon?" she said. "You are, I believe, a bachelor?"

"Your majesty's presence would be an honour in any case," I answered, "and a pleasure. I have the happiness to be unmarried."

She smiled, and sank into an easy chair.

"You will bring me the news?" she said.

"In a very few moments," I answered. "Your majesty—"

She checked me.

"I am Valerie Nevenstein for to-day, if you please," she begged. "If to-morrow I become a queen again, you will call me what you will." I bowed.

"I am not a courtier," I admitted, "and, with your gracious permission, Mademoiselle Nevenstein will come more easily to me."

"Valerie Nevenstein," she reminded me.

"It is a long name," I said thoughtfully. She looked up at me and laughed. At that moment I realized that she was really only a girl.

"If you should find it too long," she said softly, "you may choose which half you will."

Reggie's voice was in the hall. I was forced to go.

"There is no name in the world I like so well as —Valerie," I said, with my hand upon the door.

"Very well," she said, smilingly dismissing me; "you have chosen."

I found Reggie, as I had expected, in a state of great excitement. He was walking up and down the room when I entered, muttering to himself. He stopped short at once, trembling all over.

"I believe you knew!" he cried. "You knew who it was!"

I nodded.

"It was Harris, I suppose?"

Reggie sank back into a chair.

"Yes, it was Harris," he declared with a little shudder. "They sent me to Charing Cross Hospital —he had been moved there."

"You did not tell them who he was?"

"No. I simply said that it was not Shalders. Do you suppose that it was Harris whom I followed to England—Harris who stole the letters?"

"I never had the least doubt about it," I answered. "The shooting party was a myth. He came back with or without an accomplice, opened the safe with the Embassy keys, or with a false one, which he could easily have had made. He gagged and chloroformed Shalders, and when he was helpless got him somehow up into the attic. Then he started for England, giving the name of Shalders to put you off the scent. He was followed, of course, by agents of the secret police of Marianburg, and the end of that you know. The all-important question to us is, What had he done with the letters? Now I am beginning to be afraid that he either disposed of them or sent them somewhere through the post from Paris."

"But for what purpose?" Reggie exclaimed. "Granted that he was blackguard enough to steal them, what was his object? What use could they have been to him?"

"As to that," I answered, "I have a theory which I am going to test before I explain it to you. It will take me the rest of the day. How can you occupy yourself?"

"I shall write—to her," he said.

I laid my hand upon his shoulder.

"If I were you, Reggie," I said, "I would employ my time more profitably. If you write to her, I do not think that she will read it."

"What do you mean?" he cried fiercely.

"It is no use being angry," I said. "You will have to face facts. I have had direct communication with her since I have seen you. She will never forgive you!"

He dropped into a chair and covered his face with his hands. He asked no questions. He was, I think, already convinced of her unchanging anger. I laid my hand upon his shoulder.

"Come," I said, a little impatiently, perhaps— almost roughly, "come. You did not seriously intend to drivel away your life, the cavalière servante even of a queen. You have offended, and she will not forgive you. In the end you will be glad of it, but for the sake of the past, you owe her something. Don't give way like a girl. See this matter through first. There is just a chance left."

He sat up, pale and red-eyed, and listened to what I had to say.

"I want you," I said, "to describe the packet to me as carefully as you can."

"It is about eight inches square," he said, "quite thin, and it is tied up with white ribbon. The packet itself is of Japanese white silk, stained a good deal with crushed violets. The loose letter was just folded up and slipped underneath the ribbon. There is a ring inside, up in the left hand corner."

I nodded slowly.

"I shall remember that," I said. "Now, Reggie, I shall be away, perhaps, for the rest of the day. I want you to go to the club, and wait there for me. I might want you at any moment, and I want to be sure of finding you."

"Cannot I stay here?" he asked. "I don't want to see a lot of fellows I know."

"No," I answered firmly. "I want you to be at the club, and to show yourself. I want you out of the house, Reggie, in ten minutes."

"You will send for me," he begged, "as soon as you can?"

"As soon as I can—I promise that," I answered. "It may be some time. The longer I am, the greater the chance of success. Remember that, and it will help to pass the time."

Reggie left the house in a few minutes. Then I went back into the drawing-room. My visitor was still there, but she was lying upon the couch, and did not look up at my entrance. I walked softly up to her. Her eyes were closed, her head was thrown back upon the cushions—she was asleep. I walked softly away towards the door, but before I reached it some instinct prompted me to return. I stood looking over her for several minutes. After all, was my brother's infatuation so wonderful a thing? Even here, asleep, and in her travelling clothes, she was a beautiful woman. I could very well believe that, as the central and all-important figure of a brilliant court, she would be almost irresistible.

She woke, and found me looking steadfastly at her. Without any trace of embarrassment she sat up and smiled at me.

"Well," she said, "is there news yet?"

"Of a kind," I answered, "there is news. The man who was murdered at the Hotel Maurice was Leonard Harris."

"What, Sir Henry's secretary?" she exclaimed.

"Yes."

"And the packet?"

"There were no signs of it."

"The young man, Harris," she said to herself softly. "Well, after all, it is the insects who are venomous."

"He had cause, perhaps?" I ventured.

"Oh, I was rude to him once," she interrupted. "He was a boorish young man, and he presumed. But if it was he who stole the packet, I do not see why it was not in his possession."

I sat down by her side. She had moved her skirts in a manner which indicated her desire that I should do so.

"Your majesty," I said, "I fear the natural presumption is that he had parted with them."

"In which case," she remarked, with a look which rebuked my inadvertence, "they are in the hands of my enemies."

"I have," I said hesitatingly, "a vague theory as to what may have become of them. It sounds so far-fetched, and it is in itself so improbable, that I would rather say nothing to you about it for the present. But, with your permission, I will spend the morning testing it."

"You will leave me again so soon?"

She certainly had wonderful eyes. I found it safer to look downwards at the carpet.

"In your service," I murmured, "and with the utmost regret."

"You will be—as quick as possible?"

"You may be sure of it," I answered.

"And am I to remain here until your return?"

"If you will. I shall give you into the charge of my own servant, and will see that you are undisturbed."

I rose from the sofa. She gave me both her hands.

"My friend," she said earnestly, "you are very good to me! Whether I remain a queen or become a woman, I shall not forget it!"

In less than half an hour I was riding slowly down the Row, exchanging the barest greetings with the people whom I knew and carefully avoiding every one likely to detain me. There were a great many on horseback and a crowd of promenaders, but for a long time my search was a fruitless one. I had almost arrived at the conclusion that I must try some other means when, at the corner, I came face to face with two girls riding slowly and followed by a groom. The elder one, dark and moderately handsome, but without any special distinction, bowed to me graciously, and, to her evident surprise, I reined in my horse beside her.

"Good morning, Miss Ogden," I exclaimed, "I was beginning to think that you had given up your morning rides. You were not here yesterday, were you?"

"Yesterday, and the day before, and the day before that," she laughed. "There are so many people, and you seem to know them all!"

"They are a great nuisance sometimes," I remarked. "Don't you think that it is a great mistake to have too many friends?"

She shook her head. "Perhaps. My sister and I are not troubled in that way, are we, Carrie?"

The younger girl agreed, a little dolefully. I leaned over in my saddle.

"Won't you introduce me to your sister?" I asked.

Miss Ogden did so at once.

"Yesterday," she remarked, "you were riding with the Countess of Appleton. I think that if I were a man and riding with the Countess of Appleton, I should not see any one else. She is very beautiful, is she not?"

"She is my cousin, so I am scarcely a fair judge," I remarked, turning my horse. "May I come with you a little way?"

She was surprised, but frankly acquiescent. I had the advantage of belonging to a set of which they were not members, and my offer, therefore, especially as my acquaintance with Miss Ogden was of the slightest, was obviously welcome. I had danced with her a few nights ago to oblige a worried hostess, and had found her a pleasant, sensible girl.

She did not hesitate, as we rode slowly down under the trees, to admit their somewhat doubtful social position.

"It is quite interesting for us to be with some one who knows everybody," she remarked. "You see, this is only our second season, and until this year we never had a house in town. I suppose that is one reason why we know so few people outside the political set. Politicians may be useful creatures, but they are not amusing."

I laughed softly. Sir James Ogden was a politician who had worked his way up from the ranks. He had been a provincial manufacturer, mayor of his city three times, and knighted for a liberal entertainment of royalty. He had gone into Parliament, and, with the aid of a fluent tongue and a large business capacity, had worked his way into office. His methods were not altogether to the liking of his party, and he was yet to a certain extent unproven. But, on the whole, his success had been remarkable.

Unfortunately, he had married early in life, and his social prospects were hampered by a good-natured but uneducated wife. As usual, it was the daughters who suffered. London was a fascinating but unknown world to them, and there was no one to be their sponsor.

I rode slowly down between the two girls, receiving a good many surprised salutations, and doing my best to make myself agreeable—a task which, under the circumstances, was not difficult. They fully expected, as I could see, that I should leave them in a minute or two; but I did nothing of the sort. I answered my cousin's imperious little movement of her whip with a bland smile and an indifferent wave of my hat, thereby offending her grievously, and remained with them until the people began to thin off. Then, as we were walking our horses and talking under the trees, a stout, red-faced old lady rose up from a chair and waved to us. Miss Ogden's cheek flushed, but she reined in her horse at once.

"It is my mother," she remarked. "I quite forgot that she was looking out for us. I am afraid that we must go to her."

"By all means," I answered cheerfully. "By the bye, I have not the pleasure of knowing Lady Ogden. Won't you present me?"

"With pleasure," she answered readily. "Come, Carrie."

We rode up to the railings, and I was formally introduced. Lady Ogden was flustered but good natured. As it happened, nothing could have been more fortunate for me than this meeting. Lady Ogden was nothing if not hospitable, and before we had exchanged half a dozen words I was asked to luncheon. The two girls exchanged glances of resigned dismay, which speedily changed to surprise when I at once accepted the invitation. In a few minutes we rode off together again with Lady Ogden's carriage close behind.

I am free to confess that my behaviour that morning was the behaviour of a snob. Regarded from a certain point of view, it was inexcusable; yet, under similar circumstances, I know that I should do precisely the same again. I traded upon my position with the object of ingratiating myself with Lady Ogden and her daughters. I promised them cards for certain forthcoming events (a promise, by the bye, which was faithfully kept), and I was able to give them a good many useful hints and information with regard to their new position, its possibilities and obligations. I am quite sure that my luncheon at their house that day was regarded, both by Lady Ogden and her daughters, as the most important event which had happened to them since their arrival in London; and if to a certain extent I allowed them to be deceived as to my motives, I have at least made a very full atonement. The present social position of Lady Ogden and her family is largely owing to my efforts; and if Miss Louise looks a little reproachfully at me in the Park, when for several mornings I fail to speak to her, she is at least frankly grateful for the services which I have rendered them. Further, Lady Ogden can always rely upon me for one of her dinners; and nothing would induce me to be absent from any social function at her house to which I am bidden. I have been to a certain extent their good angel, and there are now very few houses in London which are not open to Lady Ogden and her daughters. Still, I fancy that none of them—except Sir James, who will keep his own counsel—have ever quite understood that morning. And beyond the fact that I have striven so hard to atone for my abuse of their first act of hospitality, there was my motive—strong enough surely to make a man unscrupulous. There was always before me the remembrance of my brother's white face, and the image of the woman who waited for my final effort. A queen to-day, tomorrow, if I failed, an outcast. No! I behaved like a cad, but I am only thankful for the inspiration which suggested this forlorn hope.

Luncheon was prolonged to its utmost limits. I talked to interest Lady Ogden and her daughters, and I succeeded. Sir James listened with a somewhat forced air of attention, but on the whole I could see that my presence also gratified him. He professed to be too busy, to have no tastes for society; but it was easy to see that as an ambitious man he was annoyed and irritated to find himself so small a figure here, and his social pretensions ignored, after his provincial triumphs. Evidently he had been told to make himself specially agreeable to me; he did his best, but, during luncheon at least, he had but little opportunity. The girls were really bright and naturally well-bred. They talked by no means badly, and we found plenty to say.

After luncheon, which was protracted as long as possible, Sir James proposed a cigar and cup of coffee in his room. I took my leave of the ladies, and followed him into the library.

"I have just one hour which I can call my own," he remarked, wheeling out a chair for me. "As a rule it is the only idle one of my day. I am old fashioned enough to enjoy my luncheon more than my dinner."

A servant brought liqueurs and coffee, and Sir James produced some cigars and cigarettes. I helped myself, and, whilst I sipped my coffee, looked around the room curiously. On the table was a black dispatch-box. Sir James, with a word of apology to me, took a bunch of keys from his pocket, and opened it. The match with which I was lighting my cigarette went out in my fingers, and my heart gave a quick beat. I was right then! A strong odour of crushed violets floated out into the room.

Sir James looked steadily into the box for several moments, with a faint smile on his lips. Then he carefully pushed it a little further back upon the table, and, lighting a cigar, stretched himself out in an easy chair opposite to mine. He began to talk at once on different subjects. Without being in any sense of the word a politician, I had made several speeches in the House of Lords upon subjects interesting to me, one of which had provoked considerable discussion. Sir James and I, being of the same party, our conversation naturally drifted into political channels. A chance remark from Sir James very soon gave the opening I desired. As carefully as possible I led the conversation up to the subject of our relations with a certain foreign power.

"If I were a genuine politician," I remarked— "that is to say, if I possessed the requisite ability to become one—I should be interested more than anything in foreign affairs. Diplomacy has always been a very fascinating study to me, although, of course, I have had no experience, and am ignorant even of its rudimentary principles. By the way, I was interested in what I heard last week—you can guess where—about a treaty with the power in question. There are some peculiar complications, are there not?"

"There have been some very peculiar complications and some unusual difficulties," Sir James remarked, smoking his cigar with evident relish, and gazing, with the ghost of a smile still upon his lips, into the depths of the open dispatch-box by his side.