RGL e-Book CoverŠ

Based on a painting by Maynard Dixon (1875-1946)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book CoverŠ

Based on a painting by Maynard Dixon (1875-1946)

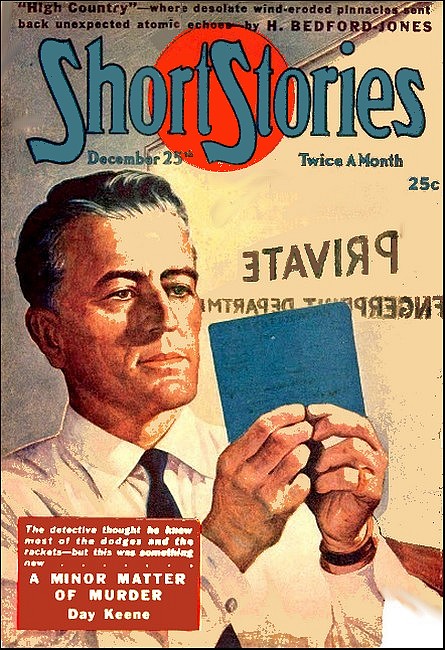

Short Stories, 25 December 1945, with "High Country"

It's Quite a Picnic When They Carry Guns in the

Lunch Basket—and Atomic Echoes Are All Around.

LOOK at Johnny Devine, now—tall, raw- boned, straight-eyed, with a lift in his step and a lurking twinkle in his thin lip-corners, and a whipcord pull in those long arms that would astonish you.

What did you do in the war, Johnny? The hell with it; save it for the papers, he would reply, and left it at that. This was no answer, as he knew in his heart, for there were echoes that would outlast all questions, but he did not expect to run into such big echoes that morning he got the Tres Piņones call, especially atomic bomb echoes.

He left the garage in charge of Mike, who was competent to handle all comers, and drove off in the trouble-shooting repair coupe. He was quite cheerful, as usual; the garage was making money, he was planning to get a new car agency, and the future looked good as it often does. Recently as the war had ended, its memories were already dying out.

Tres Piņones was eighteen miles, away, in the higher country. As he drove up the Green Caņon road, he was thinking, not too hard, about that girl over in Las Vegas. She was interesting, certainly, but Devine could not quite convince himself that he was in love. Actually, he found this southwest country far more interesting. Ever since he had been stationed at Camp Percival he had promise himself that he would return here after the war and settle down. Now he had done it.

Green Caņon fascinated him, with its desolate wind-eroded pinnacles and bleak waterless hills, as he headed up for the mesa beyond. Tres Piņones was a railroad water stop, little more, but there were dude ranches in the vicinity and the hills around were dotted with luxury-camps of wealthy folk who sought the bright winter sunshine. These were usually serviced and supplied from Morgantown, twenty-odd miles north. The car that was broken down lay this side of Tres Piņones.

"Some day, I'll have a place over there where the money lies," Devine told himself as he emerged from the upper caņon to the mesa upland. "Meantime, I'm doing all right. Good dividends in a distance call like this, too."

He would not have left the desert country on a bet, just now. He loved its hot dryness, the brilliant sunlight, the electric tang in the air even when it was blistering. Still, the high country was mighty fine, with its green hills and trout streams; a man might do worse. It depended partly on human contacts. Johnny Devine, who had left all his contacts back in Jersey, was content to make haste slowly. He was making money and was not pestered by the urge to shift too rapidly. He had shifted from Germany to Okinawa, which was plenty.

The call had come from Bill Edwards' filling station and chow house five miles this side of Tres Piņones. As Devine approached across the flat mesa, whose only horizon was the sky, the filling station came into focus and he saw the car standing beside the pumps. A luxury car, big and black and powerful, of pre-war vintage.

Bill Edwards was putting oil and water in the car when Devine drew up, halted and jumped out with cheery greeting.

"High, Bill! Here we are. Is this the wreck?"

"Hello, Johnny. Nope, the wreck is inside, laying down.

"What's the big idea?" Devine stared. "Getting me away up here for nothing—"

"Don't start beating your gums, Johnny. The guy is laid out; altitude got him. He'll pay well to be driven to where he's going. I can't leave; my wife's sick, I'm alone here."

"Oh!" said Devine, comprehending. He walked into the building.

The man was lying on the old couch under the tire-rack. He nodded to Devine. He had bright eyes in a white face, was well dressed, and looked about forty.

"You're Devine, eh? My name's Carter. I heard what you just said; don't blame you." He spoke without moving. "My heart's given out. I must be driven to Horton's place at once. Set your own price."

DEVINE asked where Horton's place was. Carter informed him;

one of those luxury cabins in the hills. Devine set his price and

made it a good one. Carter, without rising, produced a stout roll

of bills and peeled off the cash; he peeled off another bill to

pay Bill Edwards, and asked no change.

"Gimme an arm into the car, will you?" he said.

Devine complied; the man was all skin and bone, apparently. Devine wanted to grab a cup of java at the counter but Carter dissented. There were sandwiches and coffee in the car, he said. He got placed comfortably in the big back seat, a rug drawn over him to the eyes, and Devine climbed under the wheel. A wave of the hand to Bill, and they were off.

"I suppose you were in the war?" Carter asked.

Devine grimaced. "No. I was taking a course at Oxford when the incident happened."

True enough, in a way; he had enjoyed a six-weeks' course there, anyhow.

"I didn't ask for sarcasm," snapped the man behind. "Stop at the top of this grade and we'll have a bite and a sup. On the seat beside you is a briefcase. Take care of it at all costs; if anyone stops us, don't let them get it. Horton must have it today."

DEVINE had noticed the leather case, almost flat. He

investigated the seat and found it moveable, and slid it back a

notch to give his long legs more room.

"If anyone stops us!" Not likely, he thought, with a sniff. The endless brown country had no life. At the top of the long grade he could see on ahead. Nothing moved, except the heat-shimmer. He pulled out of the road and stopped. Carter made an effort, pulled himself up, and looked down at the empty front seat.

"It's gone!" he exclaimed sharply. "Where is it?"

Devine chuckled and pointed down. "Under the seat. Put it on the floor and slide it under. Nobody would ever suspect or look there."

Carter sighed, relaxed and seated himself again.

"You're all right," he said. "In this basket you'll find thermos bottles and grub. Will you get it out? Any movement sort of gets me."

No conversation was made; both men were hungry. The sandwiches were good, the coffee was better. Carter indicated a carton of cigarettes and told Devine to help himself, which he did, then broke the silence.

"Horton's my lawyer. He's a bang-up lawyer, too, on his vacation just now. I feel pretty shaky, and there's more altitude ahead; if I blackout, just leave me alone and get there. Minnie Horton will know what to do; she was a nurse. Savvy?"

Devine nodded. "Okay. I forgot something. How do I get back?"

"One of them will drive you back to your car."

Carter leaned back and closed his eyes; he was not garrulous. Devine sent the powerful car whirring up the long road toward the hills that opened ahead. Up there it would be a seven thousand foot altitude; the engine told him they were climbing all the time.

A rum go, he told himself. Why was Carter alone, in such condition? On the lam, perhaps, running to his mouthpiece? Maybe. Hard to say. Anything was possible in this cockeyed world—even here out of the world. The old car was a beauty; it made his heart sing to rev her up thus, between road and sky!

But ahead, the highway ended and he must take to dirt roads. He neared the turnout and glanced around; Carter seemed asleep, and he made the swing gently and was away on a rising yellow road that bored in among low hills, higher ones beyond, crowned with trees. No more speed; the curves became acute and must be negotiated with care, since there was barely room for two vehicles to pass.

Devine passed a couple of turnouts, and knew he must be within two or three miles of his destination. He drew the air deeply into his gratified lungs; these pine-clad heights were very different from the desert mesa they had left far behind! An instant later, however, he caught his breath with a gasp and stepped on the brake hard.

The road-block was tiny but efficient—a ditch six inches deep dug across the yellow road. On either side a man came out into view; both men were armed with rifles, and the weapons were levelled. A third man stepped forth, waving his hand.

"Take it easy," he said, quite unnecessarily, and came forward to the side of the car. A massive, roughly dressed man with rocky features and hard, glittering eyes that flicked over the car and bored into Devine.

"Well?" said the latter coolly. "What's the meaning of this?"

THE big fellow looked in at the open window. Devine glanced

around. Carter lay with eyes closed, breathing heavily; he had

passed out.

"Playing possum, is he?" came the response. "Who are you? Talk fast."

"You're nuts," said Devine. "The altitude got his heart and I was employed to drive him where he's going. Who the devil are you?"

"Jess Gorham," said the big man amiably. "Carter's up to his old tricks, eh? Well, young feller, you hop out and you won't be hurt. Hop out!" He turned as he spoke and waved his hand. "Come on, boys! This is it."

Devine scowled. "Listen, whoever you are—is this a holdup? You're not setting me afoot if I know it."

An automatic was thrust up at him and over it glittered Gorham's eyes.

"I said you won't get hurt. Act foolish and you will. We don't want you; we want him. Hop out and walk across the road and stay there till we're done; then you can take the car and go where you like. Move!"

The safety catch was pressed off, the automatic was alive. Devine pushed open the car door and got out. The two men with rifles were approaching the car. He wisely did as ordered, walked across the road, and stood there watching.

The whole thing was crazy; it did not make sense. The three conferred briefly, then Carter was hauled out of the car, still unconscious. Two of the men lifted him away in among the trees. After a moment they returned, shaking their heads. The three fell to work at the car.

Two suitcases were taken out, then they went through everything. The leader, Gorham, struck Devine as being distinctly bad medicine; the other two were ordinary rascals. What puzzled him was his inability to place them. Neither clothes nor speech indicated them as local inhabitants; certainly they were not dude ranchers. He tried to catch what they said but could not, but he had the notion that they were not talking English. Spanish, perhaps? He could not say.

They searched the car rapidly. Devine understood that they must be looking for the briefcase, thanks to Carter's words. It was not turned up. Then Gorham came over to him, and the other two, with the grips, went back among the trees.

"You can pull out in five minutes," said Gorham. Now Devine sensed a faint trace of accent, or fancied it. "Carter's staying with us. You're going to Horton's place?"

"Carter was going there," said Devine. "I expect I'd better deliver the car with news of him. You know that kidnapping carries the death penalty."

Gorham laughed silently. "Don't be a dumbhead. You tell Horton I said to come across with what belongs to me, or he'll be next; and any police interference will be very bad luck for him. That's all."

He turned and strode away. Dumbhead! That sounded foreign, too; for the moment, Devine could not place the word at all, but somehow it had a familiar ring. Gorham had not spoken with bluster, but with a cold, steely flatness that showed he meant his words literally.

Devine went over to the car, which was in considerable disorder. He did not look under the front seat; he had no need. He straightened things up a bit, then got under the wheel. As he did so, he heard the thrum of a car starting, somewhere nearby. So Gorham and his friends had their own car among the trees!

He started the engine, drove into the road, passed the ditch slowly, and quickened speed. He had to watch now for the turnout marked with Horton's name; the house would be a quarter-mile off the road.

"I've done my job. It wasn't my business to protect Carter; I'd have needed a machine gun," he reflected. "Horton gets the briefcase and the message, and drives me back to my car, and I'm done. No police interference, eh? The whole thing looks screwy, if you ask me."

Nobody, at the moment, asked him; but, in point of fact, as yet he hadn't seen nothing. Nothing!

HE turned into Horton's short, curving road. The place was fenced in with wire, and before he had gone fifty yards, he was halted by a State trooper sitting his bike in the middle of the road. "Name and business," said the trooper. "Message from a Mr. Carter to a Mr. Horton," said Devine curtly.

"Go ahead," said the trooper, removing himself.

Devine drove on, reflecting, that the cop was placed where, unseen, he could see the road entrance. More funny business.

The house came into sight, and astonished him with its size. It was large, sprawling along the hillside, and was built of logs. Garage and stables stood close by. It must have cost a small fortune, he thought. The road looped around; he made the turn, headed the car for the return trip, and halted it. Then he got out and looked for the briefcase. In order to retrieve it, he was forced to slide out the front seat entirely; there it lay, a plain leather case stamped with no name, apparently empty. He picked it up and worked the seat back into place.

"You'd better bring it up here," said a voice.

He looked up, saw a young woman standing on the log porch, and waved a hand.

"Coming." He started for the porch. She spoke again.

"You're not Mr. Carter. Where is he?"

"Detained en route," said Devine. "I'm looking for Mr. Horton."

"So am I," she rejoined. "I'm his daughter, Minnie Horton, He drove out two hours ago to meet Mr. Carter. Didn't you see him?"

Devine stood on the top step, looking at her, and it was no waste of time. She wore khaki blouse and skirt; she was dark, trim, efficient and despite a worried gaze had a charming dimple at the corner of her mouth.

"There wasn't a car on the road anywhere," he said, and caught the flicker of alarm in her eye. "Why didn't he take that cop along with him?"

"He was afraid for the place. For me." She held out her hand. "I'll take that."

"Nope. For Mr. Horton, said Carter. That's funny! Only one road—hm! Maybe Gorham got him, too."

She made a helpless gesture. "You'd better sit down and talk—fast."

Wicker rockers stood on the porch. She took one, Devine another; he gave his name and told how he came to be here. She listened without a word, but her dark eyes were eloquent, and flashed again as he told of the meeting with Jess Gorham, and what had happened to Carter. But her anxiety, he thought, was stilled.

"I see," she said, when he had finished. "Then you didn't come from Morgantown; that explains it. Father thought you would come that way. He must have gone there."

He nodded. "Maybe. I wouldn't know."

From within the house came the insistent reiterance of a telephone ringing. She rose.

"Wait—no, come along. That must be father calling."

Devine followed her into a big room garish with Indian rugs. A phone stood on a table and she picked it up. He lighted a cigarette and waited. She broke into a laugh.

"Oh, good! I thought it would be you. Mr. Carter's car came—his driver said they hadn't sighted you. No, from Tres Piņones. That explains it—what? No, just the driver. Mr. Carter was taken off by some men, on the way here. The driver brought his briefcase and won't give it to me. Says it is for you only."

She broke off, listening. Her eyes went to Devine. She beckoned him.

"Will you speak to my father, please?"

Devine nodded, took the phone, and answered. A harsh voice barked at him.

"I'm Horton; my daughter vouches for me. Will you let her look at the contents of that briefcase?"

"Oh, sure," said Devine.

"Do it, then. Was Carter hurt?"

"I think not. He had blacked out—his heart."

"The blasted fool! You don't know who the men were?"

"One Jess Gorham was the boss. Sounded foreign, somehow; a very bad actor."

"Huh. I thought so. All right, put my daughter on."

DEVINE complied, but first gave Gorham's message about the

police. Minnie Horton took over, accepted the briefcase from him,

and slid it open. There was nothing inside except an envelope

addressed to Horton. She so reported, then, evidently on demand,

opened the envelope and drew out a check. Devine looked down at

it and caught his breath. It was a cashier's check, issued by a

St. Louis bank, for three hundred thousand dollars—and it

was payable to Bearer.

"Worse fool than I thought him," came Horton's voice. "Now we're in for it. All right.

"Tell this man to stay. Send the cop away—no use now. I'll be back before sunset. Better tell that cop to come over here and escort me back—"

Devine moved away, not wishing to eavesdrop on the conversation. He smoked, looking about the luxuriously rough big room. No lack of comforts here, evidently; Horton must be a bigshot lawyer, because a place like this spelled money. Hm! Three hundred thousand—and payable to Bearer! No wonder Gorham had wanted that check—

She hung up, and faced him. "Did you hear what he said? You'll stay till he gets back? Better still until morning."

Devine lifted an eyebrow. "Not on orders, Miss Horton."

"Oh!" Her dark eyes warmed a trifle. "Will you, please?"

"With pleasure."

"Then I'll get rid of that cop. Make yourself comfortable."

He took the envelope and check from her, slid them into the briefcase again, and she was gone—out to the porch and the road below. Devine laid the briefcase on the table and took a chair. His garage shirt and jeans were, at least, clean.

He was, quite naturally, curious. Anyone who would buy a check of that size made out to Bearer should have his head examined. This affair seemed to be an odd mixture of police, lawyers and crooks; it made no sense.

"But this Minnie Horton—she's really something," he told himself emphatically. "I'd better stick around, sure. She's not the kind to be mixed up in a mess with crooks. Gorham was one if I ever saw one."

He rose, walked about the room, looked at the bright pictures by Indian artists, and caught sight of something standing in the corner half behind a curtain. It was a Marine rapid-fire carbine and the magazine was loaded; he examined it with interest.

"You seem to know your way around with it," she said.

He looked up, grinning cheerfully. "You sure sneak up on a guy. Yeah, I ought to; could take it apart in the dark, you bet."

"It belonged to my brother. I left him on Okinawa."

"You left him? Not likely. Oh!" he checked himself. "That's right. Carter said you'd been a nurse. Well, never mind; I haven't sprouted gray whiskers yet."

Her eyes were half puzzled, half laughing, as he replaced the carbine.

"What have whiskers got to do with it?"

"With me. I took a vow, cross my heart and hope to die, I'm never going to open my face about it until I've got long gray whiskers and a couple of grandchildren to scramble over my knee."

"What on earth are you driving at? About what?"

"That thing they called a war," said Devine, and chuckled. "This is a nice place. I like it. This is the sort of place I'm going to have for my own, some day. But you must get mighty lonesome, here by yourself. I take it the house is empty. D'you think that's wise?"

SHE took a chair, lighted a cigarette, surveyed him for a

moment and then yielded to the twinkle that had carried Johnny

Devine past many an icy barrier.

"Not just at present, certainly," she replied. "We came here in order to meet and talk with Carter. He's a client."

"So he inferred. Hm!" Devine frowned. "That fellow Gorham—dumbhead, he called me. The word's vaguely familiar, in an odd way."

"It ought to be, if ever you heard much German spoken."

"Oh-oh!" Devine stiffened slightly. "I believe you've hit it! German, sure! How come?"

Smiling a little, she shook her head at him. "I don't see any whiskers."

"Meaning what?"

"It's one of the things you're sworn not to mention, Mr. Devine."

"I'd feel more natural if you'd make it Johnny, just to be formal."

"Johnny Devine? A nice name. It trips off the tongue. I suppose you're just dying to ask questions?"

"So you can be happy giving the answers? I never said so. But you came a long ways to meet with a guy who had to bust his heartstrings getting here. It's all cockeyed."

She nodded. "Sure. We thought this was the safest place of all, I mean for Carter, and it turned out just the opposite. We came for only two or three days, and now look at us!"

"I am. It's very easy. I've missed a lot," Devine said gravely. "But if I'm not leaving till morning, I'd better put away that car, since it's blocking the drive."

"While you're doing it, I'll mix a drink." She rose. "We've a room ready for Mr. Carter, so you can occupy it. I doubt if he'll be along. But—Johnny!"

"Yes?" On his way to the door, he paused.

"We won't mention the war; that's all over."

"So they say. Seems to have left a lot of echoes, though."

"That's the word; echoes! The greatest thing in all history is bound to leave echoes, good and bad. This affair of Carter's is a very big one, in a way." She was speaking seriously, even earnestly. "And we're not sure where it will end."

Devine nodded. "Echoes die away if you don't stir 'em up with another holler. See you in a jiffy."

He went out, thoughtfully, to the car in the drive. An echo of the war? Three hundred thousand dollars was no slouch of an echo, as she had just said. Once he got the full story, it might make sense, but at present it did not. Carter could be held up, robbed, kidnapped, and nothing done about it—why?

Having put the car out of the way, Devine came back into the house, to find cool iced drinks waiting and Minnie Horton thumbing over a fatly folded blueprint map. She found what she wanted and opened it.

"Ever hear of the Casa Escondida?" she asked casually.

"Hidden House? No. What is it—hello, wait! I have heard of it, too," exclaimed Devine. "Somewhere over in the back country. An Injun cliff-dwelling or something of that kind, eh?"

She nodded. "Correct. No one knows much about it. A prospector looking for tellurium ore found it during the war and reported it. He went back there and never returned. It's a bad bit of country, impossible for a car. This is a government hydrographic chart."

Devine fingered his drink, watching her.

"So what?" he asked. She tapped the map.

"Nobody is aware of it generally, but there's a road within ten miles of it," she said. "Army-built, during the war; very hush-hush stuff. It ran to where some atomic bomb experiments were being made. All over now, of course, and the road's disused, since it leads nowhere. But we could reach it by car and follow it to Caņon Escondido, as the spot is marked on the map, and take the last ten miles afoot."

"We?" repeated Devine? She smiled at him and sipped her drink.

"I certainly wouldn't take that trip alone. Father can't take it at all; he's lame. But you and I could do it handily, I think."

"Why?"

She cocked an eye at him. "You're good at one-word questions, aren't you? Well, I'm just thinking out loud, Johnny. Naturally, those atomic bomb investigators picked the most desolate, hidden, unknown back-country spot they could find. So might others."

"Oh!" said he, and wondered. "Meaning you and me? The prospect would be alluring, but not with atomic bombs in mind. I'm not having any of those babies, thanks. I saw what they did in Japan; it was plenty. If you want to go somewhere, pick a spot that's got hot-dog stands and picture shows."

She paid small attention to his words but went on, musingly.

"That experimental area is still under guard, I hear, but Caņon Escondido is well this side of there. Hm! You know, those atomic bombs are part of the biggest thing that ever happened, and lots of people who shouldn't might be very much interested in them. I'd not be a bit surprised if the men who grabbed Mr. Carter might not be there, somewhere."

Devine said nothing. She was aiming at something definite, he perceived, and he gave strict attention as she went on speaking.

"You know that before the war, Germans or German agents were everywhere, even here in the Southwest. Plenty of our Nazi prisoners were thoroughly acquainted with all sections of this country—not necessarily as spies, either, but as scientists. They spoke English fluently. Some of those agents were not even Germans. Eh?"

"Conceded," Devine said cautiously. "So far, no argument."

"There might still be something to be learned from the experimental areas, here and elsewhere," she mused. "That's probably why they're still guarded. Let's go on to another fact. Not all our Nazi prisoners were sent back to Germany. Some had escaped. Others were freed with the peace. Some of their agents here were not even suspected."

"Might be," Devine assented, conscious now of keenly awakened interest.

"Take another fact. The Germans made desperate efforts to plant their money outside of Germany, and a good many managed to do it, in Switzerland and elsewhere. Now, if some of those Nazis could get to this country and settle down here—and if they could get hold of their planted loot—they'd be nicely fixed, wouldn't they?"

"Sure." Devine nodded. "But that isn't possible; international money transactions are watched too carefully."

Minnie Horton broke into a laugh, finished her drink, and rose.

"I've dangled a lot of strings before your eyes, Johnny Devine; maybe you can pull them all together—later on. May I sweeten your drink—no? Then I'll get supper started. You make yourself at home; no help needed, thanks."

She departed.

Devine smoked thoughtfully, startled and alerted by her remarks. With the return of peace, war-time restrictions of all sorts had gone by the board.. It was quite possible that many an ex-Nazi might be at large here in the United States; there was nothing to fear from any such, of course. As to their money—hell's bells! He sat up suddenly. Could she have been referring to that three hundred thousand grand? Jess Gorham and his dumbhead expletive—was the fellow a German?

"Boy! Have I stepped into something sweet, or haven't I?" he asked himself. '"She wasn't trying to snow me; she was laying out facts, and they meant something. Sounds real fantastic and absurd, but who knows? That atomic bomb business—ugh! Still, Germans and Russians were working on that, too. Even if we've got the thing locked up, scientists of all sorts will still be working on it for the next thousand years. Hm! Let's see that map."

He reached for the folded map, which lay where Minnie Horton had left it, and opened it up.

Some search was necessary before he located the road she had mentioned; this was no more than pencilled in with dots and led to the experimental area described, also marked by pencil-dots, comprising the huge, desolate, waterless region about the Skeleton Hills.

A rough third of the way along the dotted road to this area, he finally discovered vaguely indicated hills, marked: "Escondido or Salispuedes?" Hidden, or Get Out If You Can, he translated. The caņon in question would lie about there, then; the map was frankly uncertain.

Devine studied the chart thoughtfully. It was absurd to think that he would go chasing off on such a trip, even to accompany this very charming creature; he had work to do back at the garage, a living to earn. Yet, figuring the distances, it looked like only fifty miles to where the car must be abandoned, if it were a question of exploring Caņon Escondido.

"Echoes of the war, my eye!" he reflected. "I don't want any atomic bomb echoes, if that's what's up. Not even to please Minnie Horton. Not at any price. Let somebody else have 'em."

He scowled, as he heard Minnie Horton singing while she set the dining-room table. No dark-eyed beauty was going to run him into a mess like that—no, sir! Johnny Devine had too much sense.

TWENTY minutes later Horton came home. After that, Johnny

Devine hung on hard to his good resolutions with both hands; but

he finally had to let go. Much as he might have hated the

admission, the dark-eyed baby had too much on the ball.

Horton was a pleasant man who walked with a limp and a stick. He was brisk and Big Business all over, from his hard-hitting dark eyes to his pepper-and-salt suit. Devine liked him at first sight—but, equally at first sight, was aware of something he did not like and could not put his finger on. Irresolution, perhaps. He was to learn quickly enough what it was, though at first it puzzled him.

The three sat around a cold supper. Devine told his story and gave the message from Jess Gorham. After that, Horton talked for a while, with the air of having appraised Devine and knowing exactly what he was after. He had an extremely positive manner.

"I'm going to put you to work, Devine. The situation demands prompt action, there's no time to get any of my own men here, and this bad leg puts me out of it. First let me give you the picture. Carter is a client of mine. He's a go-between for some former Nazis, now loose in this country. His business was to get hold of their money, cached abroad, and get it for them here. He's done it."

"The three hundred thousand?" queried Devine. Horton nodded.

"That's only part of it—a mere bite out of it. They got the idea that he was gypping them; maybe he was. Anyone acting for gangsters has the same temptation. Things got so he was afraid for his life. He made an appointment with me here, thinking it would be safe—but evidently they found out about it. They have spies."

"Why didn't he have sense enough to stick that check in the mail?"

"Oh, he didn't come to deliver it; that was incidental. He had to confer with me. He wanted to turn those guys in and be done with it. I agreed. He had to discuss with me how it could be done safely. There's the picture in a general way. Now, to judge from Gorham's message, they want that money or they'll get after me. Unfortunately, I'm vulnerable."

"Are you letting those yellow-bellied thugs get away with it?"

Horton bit at a cigar; he had the grace to flush.

"They're more than thugs, Devine. Smart men, scientists and so forth, not mere war criminals; it took brains to get where they now are. I never imagined they'd be around here so our rendezvous must have leaked. They want their money; that's natural. My job now, is to save my client Carter from them, if possible, also to protect myself. I'll turn over every cent Carter has paid me, gladly, to get rid of the whole thing—and turn them into the F.B.I. into the bargain, if possible. But I'll have to negotiate with them, gain a bit of time—and I can't go where they are, with my bad leg. They won't come to me."

"Why not?" struck in Devine. "They came where Carter was, today. And how does your daughter, here, know where they are? If she knows and you know, why not let the F.B.I. know and end the matter?"

Horton nodded, as to reasonable questions.

"We'd not find them; they have spies everywhere. They're here today, gone tomorrow. I found word in my mail-box today, advising me to meet them at the Casa Escondida. Took quite a while to figure out where that is."

Devine surveyed his host with mingled feelings. Probably, he thought, Horton was honest enough in wanting, to turn in Gorham's outfit, but—

"How many in the gang?"

"I imagine a very few, just the cream of the crop, from what Carter has said. They have no business being in this country, of course; the government will be delighted to deal with them, but it's no ordinary police matter, as you can see. I must parley with them, first, on Carter's behalf; second, with a view to saving my own neck and also turning them in. Minnie can do this for me. They'd trust no one else. So you go along to protect her."

"You're an optimist," said Devine. Horton was assuredly not a man to despise, but waked no enthusiasm in him. He could see the man had simply got into too deep water, was unable to deal with the sort of thing that threatened him, and was panicky.

"Why do you think I'm taking any part in this nonsense? I've got a job of my own to look after."

"You're willing to earn money, aren't you? I'll pay you well."

"Hell! You city folks from back east think money is the end of all creation! You think it'll buy anything. And you'd let your daughter—"

"I'll speak for myself, Johnny," broke in the girl, a spark in her eye. "I offered to do this, and I can do it. And you're going along for two reasons. First, because father will pay well. Second, because I ask you to go."

"Why ask me?"

"Because I want you along."

Devine met her gaze and fancied he read in it unuttered things—things that stilled his arguments and protests. He could check off Horton as being a somewhat weak sister; the daughter was far different. She was no product of city business; she could do things on her own, had been an army nurse, knew her way around among men.

AT this moment the telephone in the front room rang. Horton

went to answer it. The girl spoke quickly, softly.

"What's in your mind?"

"Huh!" grunted Devine. "I've no notion to let a gang of dirty outcast Nazi gangsters run circles around me!"

"Neither have I," she said. "I'm thinking of my brother, back on Okinawa. I had an idea you and I might think the same way about a few things, Johnny."

"Oh!" he said, startled and a little delighted. "Oh! By gosh! I get you, baby."

"Hope so." She leaned back, as Horton returned.

"Okay, Mr. Horton," Devine said. "I'll go."

"Splendid! That's fine! Just one thing—you must be very careful, you know. Don't do anything foolish. Don't lose your head."

Devine, from a corner of his eye, saw the girl's lips twitch slightly, and nodded.

"Oh, yeah; that's right," he said solemnly. "I'm always careful, sir. I wouldn't want to get into any trouble, not for anything at all."

Horton perceived no sarcasm in this, and beamed.

"Very well, then, we understand one another. Minnie will represent me; you'll see to it that she's protected—"

"What'll I do if the gang starts to shooting? Just whistle?"

"No, no, nothing like that will happen. After all, these fellows are basically all right—inclined to be desperate, of course, to save themselves—"

"I never knew Nazis to be basically anything that I could say in front of a lady," put in Devine. "But have it your own way. You're giving the orders."

"That's the stuff. You'd better get off early, then." Horton turned to the girl. "My dear, I'll put the negotiations into your hands. Take my car in the morning; take Carter's check—it will serve to release him from their clutches. Make what arrangements seem best to you for a future contact with this Gorham—secretly, of course with the idea of having him and his friends laid by the heels, you understand."

"I understand, all right," she said, and Devine read in her voice what was lost on the other man. He could have hugged himself. He could have hugged her, too.

CARTER'S big car was left behind, and Devine drove Horton's agile runabout. He and Minnie got away early, after a sunrise breakfast. Even with a clear run of fifty miles ahead, Johnny Devine wasted no time in getting down to brass tacks.

"You come clean, sister," he said, almost before they were out of sight of the house. "You didn't get me into this mess just to play marbles. I saw you slide those guns into the lunch basket when we were packing things. Open up."

The girl beside him laughed. "All right. You don't think father is very forceful, do you?"

"Back of a city desk, I expect he is. Right now he's nervous as hell. And he didn't mention any atomic bomb business."

"That's my own bright little idea, Johnny. One of the men with Gorham, as he's now known, is a German scientist named Vogel. He was working at Bornholm on atomic experiments when V E Day intervened. It occurred to me that this gang might be here for some definite purpose, and not by accident."

"Might be," agreed Devine. "With that experimental area so close, yes. But you're packing along two guns. That doesn't tally with your dad's plea for caution and more caution, does it?"

"Father can't play this game," she rejoined. "You can. So can I. He knows that he's up against a gang of desperate rats. His idea is to holler for the cops. He's all right, but old-fashioned. Let George do it, is his motto."

Devine chuckled. "I get you, sister. He's right about one thing; this bunch of rats are smart guys. I'd say they must be tops, with quite an organization behind them."

"I've gathered as much from hearing Mr. Carter talk," she assented. "And, between you and me, I think he's about as bad as they are. I've no sympathy for him. From your story, I infer that Gorham and his friends must be comfortably settled; for instance, they passed up the big hamper of food in your car, yesterday, so they must have plenty on hand."

"Head of the class, little brighteyes. Further, they had a car of their own. And they were not afraid to let your dad know where to meet up with them."

"But that doesn't say they're camped in Caņon Escondido. For one thing, there's no water anywhere in that district. That's why it's so little known."

"Caņons were formed by water; therefore water might be found. Well, you've cleared up things a good deal. And you can bet I aim to be mighty careful, too—up to a certain point. If things go all right, let 'em stay that way."

"Right; we're agreed," she said. "But they may go wrong, in which case I'll be glad to have you along, rather than some cautious soul."

"Gal, when it's a question of my neck, nobody can be more cautious than Johnny Devine! Any guy who has been shot at by Krauts and Ringtails both, can say as much with truth. So bear down heavy on that. But if a rat bites my hand, I aim to make him pay for his bite, and pay quick. And now we can enjoy the scenery."

They struck into the main highway that would take them to the branching dirt road farther north, and made speed.

With every uncertainty ahead, the car was loaded with canteens, bottled water, food, blankets; the big lunch-basket alone would last them for a couple of days if need were. Devine had thrown in the M-l carbine at the last minute as a general precaution. He was uneasily conscious that Gorham and his friends were efficient men, and now that he knew who they were, and what, he was by no means sure of the wisdom of this trip. However, it was not his affair, and he had to make the best of things.

They came to Morgantown, a small but prosperous town, and here Minnie demanded a brief halt at the Western Union office. They resumed the road once more and it took them into the hills. Unexpectedly, they came upon the Army-built dirt road leading away toward the badlands and the desolate Skeleton Hills; it was still barred off, with signs prohibiting its use, but guards were no longer stationed here as in the past.

Devine got out, examined the spot, and came back with a nod.

"We can get around okay. Another car has done so—Gorham's, no doubt. Sit tight."

THEY bumped their way across rough ground, swung into the dirt

road, and were off anew. Fifteen minutes later, all other signs

of civilization were gone, and before them stretched the

prophetic vistas of what they would find farther

on—desolate volcanic slopes, black reaches of old lava

beds, pallid sulphur bottoms.

"I can't take your atomic investigation thing very seriously," observed Devine. "That area's been abandoned for a long time."

"It's just a hunch," she admitted. "They might hope to learn things from the soil, or from the scene of the experiments. Like picking up clues where a murder took place."

"Maybe. Anyhow, the whole thing makes better sense than it did at first. You know, if they left word where to meet 'em, they'll have the road watched. Anyone can be seen coming for miles in this country. D'you know where to look for this Caņon Escondido?"

"No more than you."

Rough as it was, this dirt road was little short of a miracle; the terrain was frightful. The thought of fighting afoot for ten miles over a jumble of lava and sulphur sinks and cactus was not joyful. Devine was keeping his eyes open, and well that he was; he braked suddenly, halted the car, then backed.

Nothing was in sight, the hills around were bare and empty. Halting the car again, he pointed off to the right.

"Look past that big bunch of cactus—to the left of it."

The ground descended from the road in a black smother of basalt and lava, into a dip; at the farther end of this dip, which was overgrown with cactus, appeared an abrupt wall—the side of a lava stream cooled a million years ago. There, neatly out of sight and revealed only by the track it had made through the cactus, was a car.

"All out," said Devine. "Better leave our bus in plain sight. Here's where we take to shank's mare, sister—I guess we can pick up their trail."

The car was parked off the road, and now began load-making; with this, the presumed ten miles to Casa Escondida looked more like a thousand. Young as the morning was, the sun was already blistering. Canteens and blankets were simple; the lunch-basket, weighted down with its two automatic pistols, was something else. Devine finally roped it on like a knapsack. The carbine he tucked under the front seat of the car and left.

"Two canteens each is a hell of a load, but necessary," he said, with a sigh. "Well, not so bad as combat kit at that. Ready? Our base is well supplied with everything, and we can always come back for more—maybe. All aboard for the mountains!"

Minnie Horton bore her share of the load, and, he noted, voiced no complaints. At this point, the shimmering hills opened and spread out, a couple of miles away; where to head for was a question. The ground was rough in the extreme and there were no trails of any sort. After searching for half an hour, they picked up signs where others had passed—a broken cactus, a cigarette butt, the scrape of boots.

Devine sighted back to the cars; then on ahead. The line pointed in between two hill-slopes.

"Might as well head there," he said. "Those slopes might widen out from a caņon, sure enough—it's all a mass of hills up beyond. We can't hope to follow their trail—at least, I can't. How does it strike you?"

"Lead on," she replied cheerfully. "Looks okay to me."

SO began a march to be remembered, across atrocious ground that was all ups and downs. It improved as they approached the hills; the sun, also, mounted higher. With the veteran's reflection that the first time over bad terrain is always the worst, Devine plodded along doggedly. The discovery of a number of small scraps of paper delighted him tremendously, indicating they were on the right track. Farther on, more scraps appeared.

"Carter must have done that," said Minnie Horton. Devine shook his head.

"Nope. They'd catch on in no time. More likely, Gorham left it as a trail, knowing your dad would be along or send some one. Well, we're heading right, that's a comfort, even if there's no sign of a caņon."

"It wouldn't be called Hidden Caņon for nothing," she declared. "Look! Ahead and to the left—see that spot of color?"

Devine sighted a faint red dot against the hillside, and could not understand it, but they made for it none the less. The naked, sun-refracting rock masses were all in a jumble, losing their regular lines at close approach. The valley into which they had entered could be seen for miles ahead, and certainly was not narrowing into any caņon.

Noon had come and gone. They made a cheerless halt in the shadeless waste, opened the lunch basket and made a meal of a few sandwiches, washed down with water from the canteens in scanty gulps; after a cigarette, they went on toward the red dot.

This had obviously been left as a marker; the rock underfoot gave no sign of any footprints or faintest trail. When Minnie, with pardonable vexation, declared that the only sane way of getting here was by air, Devine laughed.

"No use beating your gums, sister; others have done it, we can do it. And that thing looks like a red bandanna, yonder. Bet you it marks the entrance to the caņon!"

Cheered by this hope, they quickened pace, struck a patch of sand, and sighted undoubted foot-marks. A bandanna indeed, tied to a cactus, the red dot proved to be precisely what Devine had guessed. An opening showed among the rocks; without the marker they would never have sighted it. The opening widened. It was the outlet of a small caņon piercing into the hills. It remained narrow, but the walls on either side became higher.

There was not the least sign of any rainy-season water on the caņon floor, nor did any green thing show along the high rocky walls; all was cheerless, colorless, sun-blasted. With the breeze shut out down here, it was an inferno of oven-like heat. Tangles of cactus grew here, nothing else.

Devine, in the lead, quickened pace anxiously. He had long since learned that the desert sun held far less danger than did mere heat; to get "overhet" meant collapse. This, however, was certainly their goal, for a way had been hacked through the cactus, which towered overhead, and gave a clear path to follow. Also, the caņon was ascending and would probably be more bearable ahead.

Suddenly aware that he was alone, he halted, spoke, had no reply, and turned back. He came upon Minnie Horton sunk on one knee, a hand reaching down to hold herself up, her features suffused with blood.

"Sorry," she murmured. "It—it's the heat—"

As he reached her, she went to pieces and lay with eyes closed.

Devine knelt beside her. He worked fast, wetting his handkerchief recklessly, dabbing her face and neck, pouring more water over her head; then with his hat he began to fan her with long, powerful strokes. Clumping steps sounded on the stones; he was not surprised when, looking up, he saw a man approach from up-caņon.

"You picked a poor time to come," said the man. "You should come through here in the cool of the day or at night. Oh, it's you!"

Devine recognized one of the men who had been with Gorham the previous day, a young, big-nosed, hard-eyed man.

"Came to see Gorham, on behalf of Horton," he rejoined. The other nodded.

"Thought so. I'm Hans—Black," he said, pausing slightly before the last name, which was evidently assumed. Germans were not named Black. "The lady is coming around; I'll give you a hand with her. Farther up there's a breeze and she'll find it fine at the camp. Down here, the hillsides around make it like a bake-oven."

Minnie Horton stirred, opened her eyes, and with Devine's aid got to her feet. Black took her other arm. She was groggy, but made progress. The wet handkerchief at her throat was dry as a bone in two minutes. Devine realized that he himself was in pretty bad shape, but he kept at it with savage resolve. That Hans "Black" was an outpost guard, was quite obvious. Indeed, the man now said as much.

"We weren't expecting anyone quite so soon," he said, in his perfect English. They had halted; Devine was wetting the handkerchief again, dabbing at the girl's forehead. She took it from him and with a word of thanks continued the dabbing herself.

"I can get along now," she said, more steadily. Her flush had departed. "It just got me under for a minute—"

"Then I'll go on outside and remove the marker," said Black. "If you'll just keep going straight ahead, you'll find the worst of the heat is over; you can't miss the camp. You'd better lie down when you get there, miss."

Apparently he was not armed, but Devine took note of the bulge under his shirt. He turned and left them, going back toward the caņon entrance.

"All right," she said briefly, and struck out in advance. The path had become well marked now and the air was distinctly better. Devine followed her closely, but she showed no further need of assistance and his alarm decreased. When, presently, she stopped to rest, Devine gave her a drink, and she even forced a smile.

"Thanks. You look rather done up yourself, Johnny, Queer, isn't it—-how casual it all seems? That man and his pleasant manner."

"Too pleasant," said Devine. "We're in for it."

"Let's get on, then. I'm still dizzy." She paused, eyeing him. "You look worried."

"I'm scared as hell. I wish we hadn't come. I don't like it. Something in the look of that guy Black—well, it got me. He's sure of himself. I'm awful homesick."

"Quicker we get it over the better, then," said she, and started on.

JOHNNY DEVINE followed. He was not joking; there was a real

scare inside him, almost a panic. Why, was impossible to say. He

could feel something eerie and terrible, that sent a lump in his

throat and a prickle along his spine—same as going into a

sniper-ridden patch of jungle. All nerves, he told himself

angrily, and tried to shake off the feeling, and could not.

Perhaps, without being aware of it, he had glimpsed the black object ahead and from it had received a subconscious shock.

After a little, he did catch sight of it swinging there, hanging from a big jutting rock across the caņon and turning in the breeze. He crowded up alongside Minnie Horton so as to hide her view of it, and took her arm.

"Hey! Watch that cactus ahead and to the left—see it?" he exclaimed. "Thought I saw something move there..."

She watched, intently. He kept her in hand, playing her so that she would not look at the thing across the caņon. There was nothing in the cactus clump and he knew it. When they had passed it, he did sight the Casa Escondida, ahead and high up; he kept her attention fastened on it. Holes in the rock, big open-faced holes, a cliff-dwelling from ancient days, with a zigzag path that crawled up toward them. It was something to see, sure enough. And while they looked, the thing opposite them fell behind and was gone from sight.

Devine knew what it was, swinging and turning there. His stolen glimpses had shown him the bound hands, the long gangling figure, the convulsed features, of the man who only yesterday had employed him.

Carter had been hanged and left swinging as a hint to others that his captors meant business.

MINNIE HORTON was close to collapse again when the camp appeared. Two tents of some size were stretched. Jess Gorham and another man sat playing cards under the shade of, a tarpaulin propped on poles; a campfire smoked close by. As the visitors appeared, the two men leaped up.

"Hello, Gorham," said Devine. "Black sent us along. Miss Horton went under with the heat, back there. Any place she can rest for a bit?"

As he spoke, he was getting rid of Minnie's load and his own—blankets, basket, canteens—and dumping them together. Gorham, his massive rock-like features changing from surprise and suspicion to quick comprehension, ducked his head to the girl.

"Oh—Miss Horton, eh? We weren't looking for anyone to come along until later. Yes, of course; the lady can have a tent all to herself. It's cooler up in the Casa, but she might find it hard work getting up. This way, Miss. Your canteens are pretty hot—get some cool water, Morris—"

The two men bustled about with swift geniality and polite concern which astonished Devine; all was matter of fact, even casual, where he had anticipated covert hostility at the very least. The opened tent showed itself neat as a pin, cots made up and clean. When Minnie Horton had dropped with a sigh of relief, water was placed handily for her and the flaps lowered again; leaving her to privacy, Gorham and Morris rejoined Devine in the shade of the tarpaulin. Gorham came to him and passed a hand over his garments.

"After what happened yesterday," he said dryly, "I wouldn't be wearing a gun."

Gorham grinned. "Okay, relax," he said. "How does it happen you and she came? We were expecting Horton."

"He's lame and couldn't make the trip. His daughter can speak for him."

"Hm! Didn't know that," said Gorham, and exchanged a glance with Morris. "Else we might have tried to see him yesterday."

Free of his loads, Devine stretched out on the hard ground and lit a cigarette. The other two shoved their cards away and eyed him.

"Let's not pretend, boys," he said. "My job was to come along with Miss Horton and look after her. I don't think she saw Carter, but I did. He didn't hang himself."

"He did, in a way," said Morris, gravely. He was young, hard-bitten, certain of himself, like the man Black. Odd, thought Devine, how all these men seemed to be using their assumed names; they made very passable Americans, too. Since it was not his place to pry into their past, he had best keep his knowledge to himself, he reflected.

"Carter was a thief and a traitor," Gorham said bluntly. "He got what was coming to him."

"Well, it's not my funeral," said Devine. "Are you the guy in charge here?"

Gorham shook his head. He was by nature a solemn, massive, scowling sort of man, ready at any instant to erupt into action. Devine figured him as potentially dangerous; those deep-set, glittering eyes were gloomy and brooding.

"I am only second in charge. The man she must talk with is Dr. Bird. He has been gone since last night, but will be back at any time now. Tell us about yourself. You are a lawyer, perhaps? One of Horton's associates?"

Devine laughed, gave his name, told how he came to be here. Morris was obviously satisfied, he felt less at ease with Gorham. The man gave the impression that he might explode at any moment into unexpected activity. Morris stood up and yawned.

"The doctor said Carter must be looked after—he's been hanging since last night, remember," he said. Devine caught a faint wink directed at Gorham. "Shall we see to it?"

Gorham assented and got up. "The sooner buried the better, yes," he said.

They moved away together.

Devine finished his cigarette, unhurried. As he lay, he could look up at the cliff-dwelling almost above the camp. Casa Escondida—Hidden House—a good name for it. He saw long ropes dangling across the zigzag approach; evidently the place had been explored and the ropes had been left, perhaps for further explorations. This seemed to be a permanent hideout; at least, it had been prepared for such, with German thoroughness.

Devine flipped his cigarette stub into the dying fire, and yawned. He quite understood that, while Carter would probably get buried, the idea of Morris had been to keep a sharp eye on him and his actions.

He rolled over lazily, pulled the lunch basket from the pile of their loads, and opened it. Taking out a packet of sandwiches wrapped in a damp napkin, he tossed the napkin carelessly back and began to munch.

Dr. Bird, eh? That would be the Vogel she had mentioned, the Nazi physicist. Where had he gone? This was curious. Went away last night, would be back anytime.

"He didn't go to town anywhere, or to the road, or we'd have met him," Devine told himself. "Nor up to that cliff house, or they'd be in touch with him. Boys and girls, there can be only one answer—the experimental area! Minnie's hunch was right. Since the war, any guarding of that area has probably been a mere formality; yet there must be something to guard. They didn't expect Horton to show up before evening, so this was Vogel's chance to get there and back. Why? Perhaps they mean to pull out, especially after having settled with Carter. They don't know much about Horton, since they were' ignorant of his lameness, but they have some reason to think he wouldn't, be hard to settle with—in which they are right. Johnny Devine, you'd make a first-chop detective! But are these guys, with their own necks at stake, going to let you get dear, knowing as you do that they've murdered Carter? Watch out. If they also suspect that you know 'em for what they are, you're a gone coon. Your best bet might be to get one of those guns from the lunch basket and shoot these two gents, and get Black when the shots draw him—huh! Better still, crawl into your foxhole and keep your head down. Maybe it'll blow over."

HE stretched out on his back, tipped his hat over his eyes,

and relaxed. This was Minnie Horton's game to play, at the

moment, and he had better keep out. Upon this sage reflection, he

let nature take her course and dropped off to sleep before he

knew it.

He wakened to voices; and with caution riding him, lay quiet. A mutter of low voices close by—and not speaking English, either. One was exultant. Devine's German came back to him as he listened.

"It was marvellous, wonderful!" said the exultant voice. "After sunrise, we got splendid pictures. There was no trouble. I have the soil samples; they are practically certain to give us—"

The rest was lost. Devine opened his eyes, the merest trifle. Gorham, Morris and two strangers were going over the loads, carefully examining the blankets. Gorham glanced into the lunch-basket, carelessly.

"All safe. No weapons," he said. "Better have nothing but English speech, remember."

Devine stirred, yawned, and sat up. "Oh, hello!" he said, and rose.

"Dr. Bird, this is Mr. Devine," said Gorham. "And Mr. Lincoln."

Bird and his companion nodded. Lincoln was a stalwart fellow with a broken nose and heavy jaw. Bird, on the contrary, was slender and spectacled, obviously a man of great intelligence; his rounded dome was nearly bald, and he looked a bit older than his companions.

"Guess I dropped off," said Devine amiably. "Miss Horton up and around yet?"

"Hello, Johnny!" came her answer from the tent. "I'll be with you in a jiffy."

Gorham and Bird sat down, Lincoln disappeared with Morris. Devine jerked a thumb toward the cliff-dwellings, above.

"To judge by the ropes, you've explored the Casa Escondida. Find anything?"

"We made a superficial examination; as yet, the rooms haven't been explored," Bird replied rather stiffly. He was sallow, skinny in the face, deadly serious; apparently those tight lips never smiled. His gaze studied Devine probingly. "I understand you are merely a companion for Miss Horton?"

"Correct. Any objection to my having a look at the cliff house?"

"Objection? Certainly not," Bird responded, indifferently. "The path is not good, but the ropes make it quite practicable."

Minnie Horton emerged from the tent. Devine went to meet her.

"Hello! You're looking quite yourself again—worth a second and a third look!" he said cheerfully. "Here—let me present Dr. Bird and Mr. Gorham."

The two men rose and bowed.

"I suppose I'd better clear out while you're having your talk," Devine went on cheerfully. "Carter, by the way, isn't here. It seems he met with an accident yesterday."

"His heart," added Dr. Bird gravely. Devine met the girl's startled gaze for an instant and saw her face pale slightly.

"If you get your talks finished before dark," he went on, "we'd better go back after that—they tell me night is the best time to get out of the caņon."

"There is no hurry," struck in Bird, rather hastily. "The negotiations may require some little time. I shall have to consult with my—Dr—associates. If you wish to visit the cave dwellings, by all means do so."

The girl, at Devine's glance, nodded. "Why not? I'd like to have a look at them myself, Johnny. We might plan to stay over and visit them tomorrow."

"Certainly. We can make you comfortable," Bird said, "and Morris is an excellent cook. Will you sit down, Miss Horton?"

Devine felt himself shouldered out of the talk; he had anticipated nothing else, and turning away, sauntered past the heavy thickets of cactus up the caņon. After all, the show belonged to Minnie Horton; if everything passed off amicably, so much the better.

He was somewhat surprised to find that it was past four o'clock. Also, Lincoln appeared from nowhere and joined him, with an amiable nod. Devine provided cigarettes. His chief effort must be to keep his actual knowledge unguessed.

"This caņon is certainly a cockeyed sort of place," he observed. "Where does it start from, up above?"

"That's what Dr. Bird and I have been trying all day to discover," said Lincoln. "We've been climbing since daylight, and I'm done up. And we got nowhere."

Devine eyed the rocks close ahead. An ancient path was worn in the cliff, running off to the right, then angling back. There was no difficulty about it, here at the bottom, but the cliff bulged up above and the ropes would obviously be necessary.

"I've a notion to go up there now," he said.

"Don't," advised Lincoln. "It's getting late, and up there one needs daylight, let me tell you. It's a spooky place. I made those ropes fast—climbing used to be my business before the war—but we've not had a chance to explore much, as yet. Too busy getting the camp established."

"Might be just as well to wait till morning," agreed Devine. "Any water here?"

"We have found a spring, a very small one, farther up the caņon. Shall we see it?"

Devine agreed, and strolled along, chatting about cliff dwellings, careful to ask no questions. Mentally, he was far more busy than appeared.

There seemed no way out up-caņon; the only way in or out lay from below. He had seen no weapons about, but Gorham and his friends had been well armed when they held up Carter. Five of the gentry in all, and except for Vogel, or Bird, they were a tough crowd.

TIME passed. Hans Black made his appearance. Gorham came and

spoke with him and with Lincoln, low-voiced and apart. Morris

showed up and took part in the discussion. Presently Gorham left

the others and approached Devine.

"Come along," he said gloomily. "You're needed."

Astonished, Devine accompanied him back to the camp. At first glimpse of Minnie Horton, he perceived something had gone wrong; she was flushed and angry. The depths of the caņon were by this time filled with gathering shadows, though sunlight was visible high above.

"Sit down, Mr. Devine," said Dr. Bird, then looked at Gorham. "Better tell Morris to get started with supper." Gorham nodded and departed again. "Now, good sir," Bird went on to Devine, "It has been decided that Miss Horton shall remain here for the present, while you go back with one of us to confer with her father."

"Oh!" said Devine. "Who decided that? We came here to settle matters with you."

"I've given in everywhere," broke out the girl hotly. "They demand this silly trip."

With an effort, Johnny Devine fought down the hot words that came to his lips. Now, if ever, headwork was needed, and badly needed. He perceived instantly that, for some reason, Minnie Horton was to serve as hostage. There was something behind it, something he did not know—and he could make a guess at it. He had to regard these men, not as what they appeared, but as what they actually were.

"It is a bit unusual, isn't it?" he asked mildly, as Gorham came back and sat down. "Why, Dr. Bird, should you want to detain a lady here? Why not detain me?"

Bird spoke smoothly. "Miss Horton is entirely safe. She is among gentlemen of honor. She shall have one tent entirely to herself, and shall be molested in no way; she is an honored guest. It will save much discussion and trouble if you consent to the plan, and leave after we have eaten."

Something in his words, something unsaid and yet hinted at, pricked Devine into active suspicion.

"Well," he said amiably, "perhaps you may be right, Dr. Bird. I know that Mr. Horton expected to make every concession necessary. Certainly I do not want to be the one to start any trouble. Let me think a moment."

HE got out a cigarette and lighted it.

Minnie was staring at him in dismay and angry surprise. He rubbed his nose, and, invisibly to the others, tipped her a wink. It was obvious that his attitude was gratifying to Bird and Gorham. Morris appeared and began to break out dishes from the closed tent.

"Why," Devine asked, "don't a couple of you guys go on the errand to Horton? Why should I go along? I'm not a principal in this affair."

"He'll believe you," said Gorham. "He'd not believe any of us, I fear."

"Eh? What about?"

"That Miss Horton is quite unharmed, is in no danger, and has sent you with word."

"Oh, I see! That makes sense, yes." Devine nodded. "Who's to go with me?"

"Gorham will go," Dr. Bird replied.

"Well, Miss Horton doesn't seem to like the idea. I'd prefer having my orders from her; why not let us talk it over?" suggested Devine pleasantly. "We've plenty of grub in our own basket. You go ahead with your supper, we'll go ahead with ours; perhaps I can persuade her that your request is reasonable."

He beamed around. Inwardly he was acutely conscious of the glitter in Gorham's gloomy eyes, and it frightened him with its implications. The feeling of crisis was strong upon him. Then Dr. Bird nodded, his thin, sallow features quite pleased.

"Why not, indeed? I regret we have no tables to offer you. Pray retain this place. We usually have our meals outside the tent yonder. Perhaps you'll permit us to offer a few items to enhance your slender meal—coffee, eh? A bottle of wine?"

"Oh, sure! We'll be glad of coffee," said Devine gladly. "We brought only water. But we've everything else we need, thanks. We'd be glad to spare you some sandwiches; they're really excellent—"

BIRD and Gorham refused, very politely.

They rose and joined Morris, who had brought a packing-case into sight and was arranging it as a table.

Devine pulled over the lunch-basket, spread out one of their blankets on the ground, and began to get out napkins and sandwiches, keeping up a running fire of small talk as he did so. Minnie Horton sat motionless, angry, perplexed.

"They're leaving us free to talk," said Devine, fixing a paper plate from the basket for her. "So do it. Looks like they don't expect any message from you to be delivered anyhow—at least by me. Better speak up and do it fast, though."

"Oh!" She wakened from her angry abstraction. "How do you—but you can't know that!"

"I can guess. You couldn't settle matters for your dad?"

"Yes, yes, of course. Only, this silly trip and message! And it's all my fault."

"Not silly; not a bit of it. Bird, or Vogel, has got everything he wanted, over at the experimental area. Don't figure these guys for silly."

"My fault, all of it," she repeated. "I let slip that you knew everything about them. I'm sorry. I meant it to help us—"

"Oh!" Devine's brows went up. "So that's what tore it! Okay, sister. Just you sit tight now. We'll have to take the lid off—but you let me do it."

His consternation was acute at her disclosure; but so was his relief. Everything was now clear. He knew exactly what he was up against. And, he thought grimly, he could take it.

NO, not silly at all; things fell into proper focus now.

Bird and his friends had accomplished their errands here. Accounts with Carter had been squared. Minnie Horton, for her father, had turned over their money to them.

Dr. Bird had obtained photographs and other data from the experimental area, which he could no doubt translate into the scientific terms he desired. And then, from the girl, had come the revelation that Johnny Devine—and she, as well—knew precisely who they were and what they were doing here! The smooth Dr. Bird, no doubt, had goaded her into some angry threat.

Alert, suspicious, fully aware of their danger, they had taken instant resolve. Devine would be sent back, presumably; but he would also be sent to keep Carter company. Minnie Horton would be retained as hostage, perhaps by one or two of the group, until Bird and the others made their getaway and were in safety with their precious secrets. These remnants of the shattered Nazi empire had their hopes and plans; let the physicist Vogel light on the secret of the atomic bomb, and only God knew what might happen. His very exultancy proved that he had located something worthwhile.

"I'm afraid," murmured Minnie Horton, staring at him in the gathering darkness. At one side, Hans Black was fussing with a gasoline lamp, trying to get it alight. All five of the company were here now, talking among themselves, careless what passed between the girl and Devine.

"I'm afraid—for you, Johnny! I don't think they—they mean to let you go—"

"Sure not." Devine laughed cheerfully and leaned over the lunch basket. He raked about in the bottom of it, found one of the two pistols there, and slid it into his unbuttoned shirt. "Now, listen to me, sister. Have no arguments; just be good. Play the game. Let's see, now—"

He lit another cigarette. Black had the lamp going now, sputtering, spreading a white glare over the scene.

"Gorham goes with me. Lincoln and the Doc are dead beat; they've been on the go since last night. Once they hit the hay, they'll be dead to the world. That leaves Morris and Black to look out for—see here, now! You turn in, but don't sleep. Give 'em an hour to quiet down, get me?"

"Yes. But it's no use, Johnny. You mustn't do anything desperate. I've snafued everything—"

"Rats! You've only hurried up what was bound to come anyhow. Don't worry about me; I'll be okay. Soon as things are quiet, get a canteen—take it to bed with you, rather. Slip out. If Morris or Black is on guard and stops you, say you can't sleep and need air. Be pleasant. Kid him along to where those ropes come down and stop there. If there's no guard, make for the ropes and see if you can climb to those cliff houses. It'll be a hell of a job in the dark, but try it anyhow. That path is good for part of the way, no loose shale or rock to fall. Got it?"

"Yes. But—"

"No buts, sister. Now play like you've come around and want to send your dad a note, and we'll be set. Getting chilly here, sure enough—that's grand!"

It was, indeed, growing cold; in these altitudes the nights were cold as the days were hot. Devine called Dr. Bird over to join them, and requested the loan of a coat.

"Take mine," said Gorham, bringing it to him. "I'll not be needing it. Well, what's been decided?"

"Oh, there's no objection," spoke up Minnie Horton, with a smile. "I'll send a note by Mr. Devine to my father—have you a pencil, and paper, Dr. Bird?"

"Yes, indeed," replied the latter, producing them. "It is nice to find that all is pleasant. Morris, where's the coffee for our guests?"

A PLEASANT gathering, indeed; hot coffee, jests, much

politeness evidenced toward the girl, and Devine wrapping the

coat thankfully about him to conceal the pistol-bulge under his

shirt. Gorham, it appeared, was actually going on to see Horton,

for he took commissions from Lincoln and Black to bring them

various small articles from Morgantown, and put new batteries in

a flashlight with which to light the way down the caņon and on to

the waiting cars.. There would be a moon, said Bird, but it would

not penetrate into the caņon depths.

Minnie finished her note. Devine took it, slung a canteen-strap across his shoulder in case they needed water, and pronounced himself ready for departure. Bird insisted on shaking hands with him—a note of Nazi falsity which he did not forget—and after a casual farewell from Minnie, he waved his hand and strode away with the gloomy Gorham.

"You have the light, so you'd better go ahead," he said, and Gorham complied at once, the radiance of the gasoline lamp dying away behind.

The pencil of light probing the blackness, they tramped along in silence. Devine calculated that he was in no immediate danger; Gorham, he reflected, would probably wait until they were out of the caņon, perhaps at the cars, before killing him; but he had no intention to leave the caņon. And yet, he realized, he could not take action on mere suspicion alone, even were that suspicion a certainty in his own mind.

As they clattered along, he took off the canteen hanging at his hip, and held the strap in his hand, close to the container. He had chosen it purposely; it was his own, and was barely half full. He hefted it with satisfaction.

They came to an open stretch, free of cactus, and he came up beside Gorham.

"I suppose a shot would cause echoes to wake the dead, eh?" he said.

"A regular volley, yes," Gorham assented.

"It'd be a pity to alarm Miss Horton."

Gorham halted. "What are you talking about?"

"Didn't you see those rabbits jumping away from the light?"

"Oh. No time to be hunting rabbits," growled the other, resuming his stride. "Come on. We must reach Horton by morning."

"I thought Vogel gave you other orders about me?"

"I don't know what—Vogel!" Gorham halted, his voice breaking out as realization came to him. "Vogel! Who told you? Who told you his name?"

"Oh, he was quite famous for his work at Bornholm—"

"Ach! You dumbhead!" Sudden furious passion took hold of the man. He halted and shifted the light to his left hand. His right darted under his shirt. "So you must have it now—all right, all right—you and Carter alike—"

Devine swung with the canteen; it struck light, man and pistol. The light fell and went out. The man staggered back. The pistol exploded, echoes roaring up the canyon walls. Devine fell back a pace or two, and dropped.

"Ach! American swine are all alike!" came Gorham's voice from the darkness. "And Vogel said to wait till we were at the caņon entrance—have to make sure of him now."

He took a step, cursing the darkness, fumbling about for the flashlight. He found it, rose, and tested it. The light flashed on—

Devine shot him from the ground. Again the echoes soared, as Gorham fell. He still clutched the light, whose beam went wild. His pistol clattered on the stones. Devine was upon him instantly, snatching the light, locating the fallen pistol, kicking it away. But there was no danger. Gorham lay clutching his breast, where blood jumped. Fright and horror were stamped in his face as Devine flashed the light on him.

"A mistake—I said it was a mistake—kill him then and there!" groaned out the dying man. "Vogel, damn him—ach, a blind fool—I said it was a mistake."

"You were right," observed Devine, switching off the light. Only a groan, and a rush of escaping, gasping breath, made reply. Gorham had gone to find his victim, Carter.

Sitting on his heels, Johnny Devine lit a cigarette—his last for a while, he reflected—and calmed down. He had taken risks, absurd risks, in the endeavor not to act upon suspicion alone; and he had been entirely justified.

He heard nothing, saw no light behind them; no one had followed, then. Those two shots would be heard, of course; it would be taken for granted that Gorham had fired them, had killed his man and gone on. Best pull him out of sight into a cactus patch, then, before going back, just in case all went well and it was possible to get Minnie Horton off and away. No hurry, now. Give Bird and the others a chance to discuss those shots and get to sleep, reassured.

HIS smoke finished, Devine remained listening for a little; he

heard nothing. The temptation that hit him was logical enough. He

was on his way out. He could keep going and reach the car and by

morning be back with help—either from Morgantown or from

the guards at the experiment area. Bird and the others would be

like rats in a trap. He grunted as he rose, and grinned in the

darkness.

"Sure would be nice, if I were alone; can't go back on a pal, though," he told himself.

He went to Gorham, flashed on the light; the man was dead. A cactus tangle was close by, and he dragged the body to it and around it, out of casual sight. Then he started on his return journey.

For the moment, he could use the flashlight, with care; but not for long. Up above the caņon ran straight, without a twist or turn; any stabbing finger of light might be seen by anyone on guard at the camp. His approach must be silent, too—damn! It was going to be a ticklish business. He remembered the other name for this caņon on the map.

"Salsipuedes—Get-out-if-you-can! That's a good name for it right now," he said. He always had liked the sound of his own voice in the darkness. "Hot damn! I'm a Dummkopf and no mistake—"

He turned and went back, cautiously retracing his steps, until he found Gorham's pistol, which he had forgotten. Then he went to the man's body and searched the shirt pockets, finding a number of folded papers. He pocketed these without examination, then once more took up his way toward camp.

While he could do so, he covered ground at a good pace. Once he took on caution and kept the light doused, it was a different matter; he had to watch his footing, and he also had to keep from running into cactus, as painful experience taught him. This, however, became less difficult as he advanced.

To his surprise, the pitch darkness at the bottom of the caņon proved not so impenetrable as he had thought. When no longer dazzled by the flashlight, his eyes found differences in the obscurity and the masses of broad, flat cactus leaves could be made out, dimly. He figured that the star-light glinting overhead must be reflected by the rocky walls of the caņon, imperceptibly yet reaching the depths with a certain faint radiance that aided him enormously in avoiding the spiny contacts.

He kept on interminably, as it seemed. There was nothing to guide him; he had to feel for each step. The white radiance of that gasoline lamp had long ago vanished.