RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old travel poster

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old travel poster

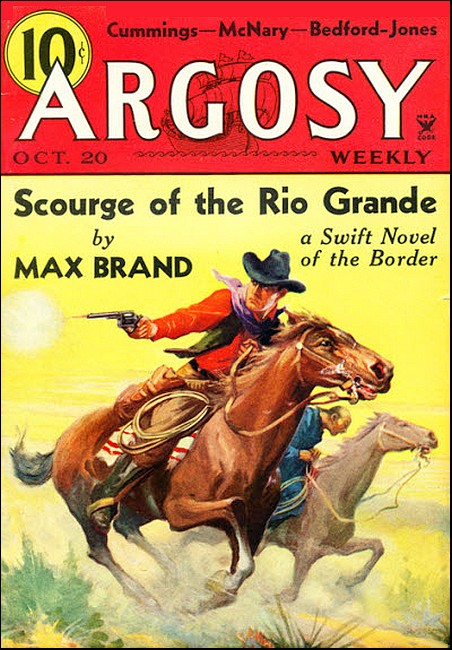

Argosy, 20 October 1934, with "The Deathly Island"

On a tiny isle off Madagascar, Captain Stuart matches wits

and guns with the most dangerous man in the Indian Ocean.

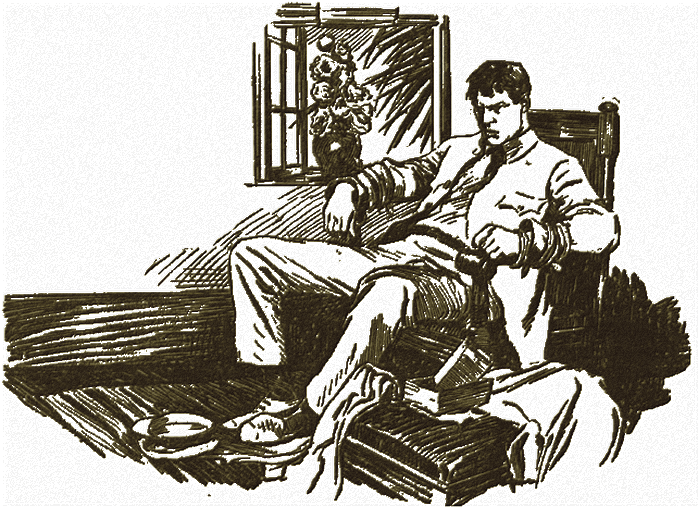

Mandrin lifted the girl effortlessly.

STUART reached Diego Suarez, on the north tip of Madagascar, on the tenth. He went ashore and at the splendid post office near Coral Point made inquiry at the poste restante, otherwise the general delivery. A letter addressed to Captain Charles Stuart was produced, and after identifying himself, he obtained it. He turned away and tore it open, to find a brief, unsigned note:

Meet me at Windsor Castle Wednesday morning about ten.

He tore up the note thoughtfully. Wednesday. That was to-morrow. He knew the writing; it was that of his brother Eben. Windsor Castle! Had the man gone crazy?

Stuart made his way to one of the sidewalk cafés, dropped into a chair, ordered a cool drink, and frowned. Eben must have received his cablegram, then. But why this insane message? It had been posted here in the city. Why didn't Eben come aboard, or meet him? In trouble, of course. He might have expected it. How often had he sworn never again to jeopardize his own name and life by pulling that worthless scapegrace out of a hole?

"And," Stuart muttered angrily, "I suppose I'll go and do it again—and again. After all, he's my brother. The scoundrel! I suppose it's forgery once more, or worse."

There was no denying the fact that Eben Stuart was no angel.

Neither was Captain Stuart, for that matter. You could see in his hard, brown, weathered features that he was not the man to avoid a fight. He was just thirty; impatient of fools, his gray eyes had a stern bite to them. But that bronzed face was level-eyed and strong. No weakness in it. A straight keen look square in the eye, and if you didn't like: it that was just too bad for you.

A man came to Stuart's table and with a murmured apology took the opposite chair. Stuart flashed him a glance, then nodded in surprise. It was one of the harbor officials who had inspected his papers.

"Oh, hello," said Stuart. "Have a drink?"

"Thanks, no. I merely desired to ask m'sieu a question."

"At your service."

"Is m'sieu, by any chance, a relation of one named Stuart, who was until recently assistant manager of the packing house?"

"The stockyards?" Stuart's lips curved thinly. "Do I look like I'd have any relatives in that business?"

"But yes," said the officer seriously. "M'sieu does not look unlike him."

Stuart shook his had. "Afraid I can't claim the honor. Is he an American?"

The other shrugged. "Who knows? Perhaps. The police have been in search of him, and it occurred to me that m'sieu, being of the same name—"

"No, no!" Stuart broke into a hearty laugh. "Why, what has he done, anyhow?"

"Different things, m'sieu. Murder, for one. He is accused of having killed the King of Amber Island and stolen his daughter's pearls, which are famous—"

"Wait a minute."

Stuart sipped at his drink, while the astonished Frenchman stared at him. Was he mad? This was Madagascar, yes, the strange, huge French colony between Africa and the Indian Ocean.

That made it all the queerer. Windsor Castle! And now the King of Amber Island.

"So," said Stuart. "This rascal kills kings, does he? Or did I hear you aright?"

"M'sieu does not understand. Amber Island is around the cape, off the west coast. It is like this," and on the tablecloth the officer drew with his fingernail. There grew the triangular outline of Cape Amber, that enormous mountain mass which forms the very northern tip of Madagascar, connected with the mainland by a narrow isthmus.

Here on the east side of the isthmus was Diego Suarez, the second greatest harbor in the world. And over to the west of the neck, the officer made a dot.

"Amber Island, m'sieu. An Englishman named Desmond bought it many years ago and made his home there—"

"An Irishman, you mean," said Stuart. "No Englishman could be named Desmond."

"It is all the same, m'sieu. He came to be called the King of Amber Island, partly in jest, partly in earnest. Well, two weeks ago he was here, visiting, with his daughter and his yacht. He was found dead in the suite he occupied in the Japan Hotel, yonder. The pearls of his daughter, pearls almost as beautiful as she is herself, were gone. This Stuart had been there, his fingerprints were found; he, too, was gone."

"And the girl?" questioned Stuart sardonically. "Also gone, no doubt?"

"But no, m'sieu! Now she has gone home with the yacht to bury her father there, but she knew nothing about the murder. Ah, what a woman! Not in Paris, not in Lyons, will m'sieu see such a young woman! Well, she will make a good island queen, with her father's money and so forth. However, allow me to warn m'sieu that if this man of the same name should try to get away on the schooner, it would be unpleasant."

Stuart thanked his informant warmly, assured him with truth that he would allow no murderer to try and leave on his craft, and then asked if there was by chance any place in town known as Windsor Castle. The officer laughed, and pointed to the map he had drawn on the tablecloth, putting his finger on the isthmus—that ridge of high, craggy peaks circling around back of the city.

"Here, m'sieu, lie two peaks like castles—Windsor Castle and Dover Castle, they are called. If m'sieu wishes, he can visit Windsor Castle easily, with porters and a filanjana; it is only twenty kilometers away. From there one obtains a view of the most magnificent."

So, then it was no insanity after all!

STUART went back to his schooner thoughtfully. Murder, eh?

Pretty bad. Brother or not, this ended the business. Certainly

Eben would get no lift aboard the schooner. Murder and

robbery—whew! "How often shall my brother offend me, and I

forgive him?" Well, this was something different, if it were

true. If!

"And I'll find out, quick enough," Stuart muttered grimly.

Once aboard the schooner, he felt better about it all; this was his home, and he was never quite at his ease ashore. Five years before, upon coming into a little money, Stuart had done what many another man would like to do. He bought this little craft and went places. He was that kind, and he had no ties to hold him down. He had found none.

For the past two years, he had been knocking about the strange and savage coasts of Madagascar and parts adjacent, from Zanzibar to Mozambique. He got on well with the French. He liked the natives. Whether or not his cargoes paid mattered little to him. A keen-faced, hungry man, always seeking, seeking he knew not what, he knew not where, ever searching over the horizon. Life meant little to him.

His seamen were Sakalavas, brown island men, merry and eager. His mate was a queer, lop-eared old rascal with a gray beard and a dirty turban; an Arab, Rais Yusuf by name, but one of those Arabs whose ancestors had been the prime seamen of the eastern seas for five hundred years. Stuart was a little aloof from them all, so that they loved him the more.

Night fell. Dinner over, he opened up a roll of newspapers he had fetched aboard and began glancing through them. When he came on the story of Desmond's murder, he grunted savagely but forced himself to read on. Yes; one Ebben—that was the way they spelled it—Ebben Stuart, an official of the packing house. He had disappeared. With a growl, Stuart cast the papers aside, then picked one up again. A picture caught his eye. The picture of a young woman, poorly printed. His eye kindled at sight of her face.

"Ah!" he murmured. "There, by gad, is a woman for you! Wonder who she is."

He looked at the caption, and threw the paper away with an oath. Mile. Felice Desmond, from Amber Island.

Stuart went on deck and stared out at the shore lights. A big city, this; a city of factories, shipyards, commerce, French civilization. Automobiles cheek by jowl with the native filanjana, the seat perched on poles that men carried on their shoulders. All Madagascar was like that, contrasts everywhere. Tropical jungles and vast mountain uplands. Cities hundreds of miles of paved roads, but no connection with other cities except by train. All in process of building. An empire slowly forging ahead. Aviation fields alongside native perfume factories, dockyards with Arab dhows at their gates.

In the morning a tourist office arranged everything. Stuart enjoyed the contrasts of his excursion; a ricksha, or push-push, as it was called here, down to the dock. Then a steam launch up to the head of the bay, where the road began. Then the filanjana. He perched in the chair as the porters swung along, and the guide pointed things out to him. He had a big lunch-basket that two of the men carried slung on a pole, all for himself; or so he said.

THE trail rose and rose, twisted, climbed. Finally, on the

mountain neck, they came to a native village with one of the

long, unpronounceable Polynesian names of the island. Brown men

from far over the sea, in a forgotten day, had settled

Madagascar, coming in their war canoes from the East Indies.

And there was Windsor Castle up above on the crest. One of those strange freaks of nature which abound in Madagascar, looking for all the world like a turreted castle, but now with a staircase ascending the precipitous sides, an easy path for tourists. Stuart climbed to the rocks above and two men brought along his lunch basket. It was still early. The guide wanted to earn his pay, but Stuart gave him money and curt directions.

"Go away. Take your men and go down to the village and stay there. I wish to be alone. After an hour, come back and see if I am ready to leave."

Well, God knows all English and Americans are mad, said the guide, and with a shrug obeyed the orders. Stuart watched the men descend and vanish from sight. Then he turned to the jumble of rocks.

"All right, Eb," he said grimly, and then lifted his voice. "Are you here?"

Eben was there. He came forth into the sunlight, a tattered, unshaven, nauseous figure, but he carried himself jauntily. Little could be seen of his face for beard and dirt; he was slender, wide-shouldered, arrogant.

"Hello," said Stuart, eying him. "Hungry, eh? Well, save your talk. Pitch in and eat, then talk later. That's my advice. You'd better follow it."

Eben flinched a little at the grim note in that quiet voice, then shrugged.

"Fair enough," he responded. "Glad to see you, old chap. I'm famished, for a fact. I have some native friends, but their idea of food isn't mine. And wine, real wine! Say, this is great—"

"Eat," said Stuart. "And save what's left. You may need it."

He turned his back and, while his brother tackled the food like a starving man, began to appreciate the place to which he had come. There were few like it in the world. Off to his right fell away the land, and all the wide Indian Ocean lay outspread there in its endless desolation. To the north towered the savage green masses of Cape Amber. To the left lay the ocean again, the Mozambique Channel, running down to the south where the Mitsui archipelago seemed to blend with the land once more. Islands by the hundred. One could see fifty miles and more from this point.

"Where's Amber Island?" demanded Stuart.

The other rose. With this question, he knew that Stuart knew everything, but little he cared. Swaggering over, he pointed. Stuart saw a spot of green, nothing more. Far away and distant, over to the westward and south. By bird flight, only a few miles perhaps, but to reach it one had to round the whole of Cape Amber.

Presently Eben lit a cigarette, rose, sighed again with repletion, and came to where Stuart stood.

"Well, we might as well have it out," he said. "You know?"

"I've heard a lot of things." Stuart turned and the gray eyes stabbed. "True or not?"

Eben Stuart chuckled in his soft, evil fashion.

"You've pulled me out of a lot, Charley," he said. "This is the last time. Now I'm made. I've got everything all fixed."

"You don't leave Diego Suarez aboard my craft," Stuart said calmly. "The police have their suspicions."

"That's all right. I don't have to." Eben nodded down the line of the west coast. "All I need is some money and I can reach Nosi Be, and once there I'm taken care of. Now I'll show you something that'll knock your eye out."

FROM under his ragged shirt he took a chamois bag slung on a

thong about his neck, and pulled at the knotted draw-strings. He

went to the head of the staircase and looked down, saw no one

approaching, and returned. Out into the sunlight he poured

pearls—two necklaces, gorgeous shimmering things, loops and

strands of iridescent loveliness.

"Look at them!" he said in a low voice, his eyes greedy. "Millions!"

"So it was all true." After one glance at the pearls, Stuart fastened his eyes on his brother's face. "All of it."

"Bosh! If I hadn't got them, Mandrin would have had them."

"And who is Mandrin?"

"That French chap. Her father's secretary. He tipped me off in the first place and got me in with 'em. He's got his own game over there, wants the girl; but he couldn't get away with the pearls. Somebody else had to do that, away from the island. He thought I was a safe one, the rat! He's learned better by now."

"So you double crossed him, eh? You would."

"Oh, I knew I could count on you, when it came to the scratch. You'll be rid of me for life now. Doesn't matter about the girl. She has plenty, and when Mandrin gets through with her she won't care about a few pearls."

Stuart turned away and looked out to sea. After a moment the cleanness of it, the great solitude of sea and sky, somewhat washed the dirt out of his heart and brain. It was hard for him to restrain himself, at first. Thought of that girl's face, of this man, of the unknown Mandrin, sickened him.

"Five thousand francs will do the trick," said Eben Stuart, now looping the pearls back into the chamois bag.

Stuart turned to him, reached out, quietly took the bag and let the shimmering pearls stream back into it. He drew the strings tight and knotted them. Then he thrust the bag into his jacket pocket and met his brother's suddenly startled gaze.

"They go back to her," he said calmly. "I'll give you the five—

"None of that, damn you!" The bearded features flushed with utter fury, purpled with a wild sweep of rage. "Hand 'em back, Charley! I warn you—none of your fine notions, now! Give 'em here."

"No," said Stuart with terrible finality. He was like a rock, uncompromising, silent.

A low, passionate oath. The glitter of steel. Swift, deadly, the other man hurled himself like a striking snake, a foamy spume of saliva about his lips, sheer madness in his eyes. Stuart grappled him, but was borne backward. That burst of insane rage carried superhuman strength. Barely could Stuart keep the knife from his throat.

The two men reeled, staggered, then lost balance and went rolling across the ground. It was a wild, furious scramble, a heaving of intertwined bodies, a thrashing confusion. It ended abruptly, without warning. Stuart found himself free, and leaped to his feet. His brother lay face down, one hand doubled under him; that hand still gripped the knife, but the knife had sunk to the heart of the man.

A cry of incredulity, of horror, of grief, escaped Stuart's lips.

After a time he picked up the basket, repacked it, and started down the staircase. The guide and natives came to meet him, relieve him of his burden. He went on down to the village and got into the filanjana again.

His face was like bronze, inscrutable, set, emotionless.

AFTER a very thorough search by police, Stuart got his clearance papers and took his schooner out of harbor late that afternoon, for Nosi Be.

With the monsoon fair, it was no trick to beat around the head of Cape Amber, but none the less it was a matter of days. Stuart had plenty of time to think about affairs. Not those that were past; he pretended no grief. Now, as always, he looked ahead.

He could not find Amber Island in the pilot guide. This Admiralty book held to the old native names; with the help of Rais Yusuf he identified it finally and learned little about it, except that it was four miles long and three wide, was fairly close to the Madagascar coast, and had an anchorage which at this monsoon was excellent.

The massive, rockbound cape fell behind, and the schooner leaned over to the thrusting monsoon and ate up the miles. Stuart had not looked again at the pearls, or even untied the chamois bag's drawstrings. They meant nothing to him, their beauty was not his. As for their money value, this was not his either; it merely drew a shrug from him. Some men are like that. Others go into a delirium when a fortune lies in their palm.

They picked up the island toward sunset, and ran in under the land for the night. With sunrise, Stuart stood down toward the anchorage. He had expected to see the Desmond yacht there, but only buoys marked the spot. Trees, from this approach, masked the entire island except for a rocky headland to the westward. At the head of the cove appeared a small wharf, with a number of sheds.

"Make fast to the buoy yonder," said Stuart to Rais Yusuf. "Then lower a boat and put me ashore. Keep watch. The usual signals if I want to come off, day or night."

No one appeared in sight. When he stepped ashore and walked up past the sheds, the place seemed like an uninhabited island. Probably no visitors ever came here; except for the native fishing boats, these seas were empty of traffic.

Then, in front of him, the trees suddenly opened out. Here between them appeared a wide, straight walk paved with dazzling coral sand. Looking up that slowly ascending avenue between the trees, Desmond saw what must be the house—a splotch of white, three hundred yards or more away. He advanced toward it.

A spot of color grew. Between the trees at the end of the avenue was a white mast. It bore the flag of France, halfway up its reach. Stuart recalled that the "king" of this island was just dead and buried. He patted the cigarette tin in his pocket and went on. The pearls lay in that tin, carefully coiled and laid away.

Early as was the hour, the morning was hot. The sun-glare on this white coral sand was refracted back tenfold. Smooth, heavy white sand, white as snow, but so thinly strewn as not to clog the feet. Queer. Stuart halted and looked along the sand with sudden astonishment. No mark of feet here; no footprint except his own.

"Hm! Looks as though they kept it brushed," he muttered, then removed his cap and wiped his brow.

Now, as he advanced, he could see the house ahead of him; a low, two-storied structure fronting toward him. All about it were greensward and gardens in an open circle, bounded and hemmed in by the thick growth of trees. As he looked, rainbows suddenly mounted in the sunlight. Misty water spurted in fountains in front of the house, to right and left of the opening between the trees. Sprinklers, of course; then there must be a pressure system and even electricity. Why not? Still, it was a surprise.

SO close grew the trees to right and left of the avenue that

they formed a green wall, impenetrable, except for arched

openings from time to time. These gave glimpses of a regular

jungle of trees and vines that lay behind. Ahead, Stuart could

now descry the circular garden space about the front of the

house. He was perhaps fifty feet from the end of the avenue when

something stirred beside him. A figure had slipped into one of

the arched openings there and was staring at him in blank

astonishment.

A slender, lovely figure, wearing only sandals and white silk pajamas, soaking wet halfway to the knees. Bareheaded. Massive plaits of blue-black hair were piled about a charming elfin face—blue eyes, slim cheeks. A thrust of character in the chin and mouth, the eyes defiant and unafraid. The face of that newspaper picture; Felice Desmond.

"Well, of all things!" she exclaimed in English. "Who are you? Where did you come from?"

Stuart had not the faintest idea of giving his name; not for a time, at least. He took off his cap and smiled, enjoying the loveliness of the picture she made, enjoying it with a frank and wholesome delight.

"Now I must believe in fairies, or rather in wood-nymphs!" he exclaimed. "Either that, or else I'm dreaming, which isn't at all likely. Fair spirit of the trees, my name is Charles, and I've come from my schooner which lies in the cove."

"Oh, indeed!" A laugh flashed in her eyes and was gone. "Well, unhappy mortal, what is your business on this island?"

"I'm not unhappy," Stuart said with a chuckle. "My business lies with a lady, whom I never saw. Her name is Desmond, but I suppose she's French in spite of it, and therefore unpleasant and probably bearded in spots, reeking with perfume instead of soap and water—"

The girl broke into a laugh like silver bells.

"Mercy! You have queer notions about Frenchwomen, wandering sailor! And just what may your business be with this female dragon? Come, confide in me; you may have need of help from the fairies before you're through."

Stuart nodded gravely. "I've no doubt of it. My business is to give her a message from a dead man, a message of warning; and to restore certain property which she lost far away from here. Can you tell me where to find her?"

Now the blue eyes probed into him for a moment, no longer laughing.

"You'll find her at the house yonder. She's a horrible person, worse than you ever imagined, but she does her best, poor thing. Let me advise you not to mention any property, lost or otherwise, until you are alone with her. As for your message of warning, perhaps she does not need it."

"I fear she does," said Stuart quietly.

"Well, go your way," she said, with a shrug. "Unless you'd like to come and wander through the trees with me and get your feet wet. It's supposed to improve one's beauty."

Stuart smiled. "That doesn't apply to fairies, whose beauty is perfect. I'd love to join you, but business presses."

"All right," she rejoined. "But remember one thing—it's a discovery I've just made for myself, and it's important. Don't drink any coffee. Good-by."

She was gone, slipping away among the trees like a fairy indeed. Stuart replaced his cap, produced a cigarette, and lit it thoughtfully.

"What the devil did she mean by that?" he mused. "Was it a warning or merely a joke? No; she's not given to useless words. Something queer here! She had a queer look, too, until I made her laugh and forget herself. White and strained. Is it possible that she's found out about that rat Mandrill? Hm. She's not the kind to stand any monkey business from him. I don't savvy it at all. One thing sure—she's great. She's great!"

It was the only word he could summon up.

THE fountains of water lowered and sank to nothing as he

advanced. He came to the house entrance, crossed the bay of a

wide veranda fitted with easy wicker chairs and lattices to keep

out the light, and swung the knocker on the massive door. Its

boom rang through the house with hollow reverberations.

A bolt was shot. The door swung back, and a brown servant stared slack-jawed.

"Good morning," said Stuart in French. "I am Captain Charles. I have come to see Mile. Desmond. She is here, I think?"

"I do not know, m'sieu." came the fumbling response. "Will you enter, please? You may wait in the reception room. I'll tell M. Mandrin that you are here."

"Tell the lady," said Stuart sharply. "I have my orders, m'sieu," Except its luxury, there was nothing regal about the reception room into which Stuart was ushered. Everything was highly expensive and very comfortable. On one wall was an oil painting of a young man over which a bit of crepe had been draped; this, obviously, was the girl's father. His face was like hers, and the character behind it.

A rather small man in a red silk dressing-gown came into the room.

"What a surprise!" he exclaimed. "I did not know any vessel had arrived. I am Jules Mandrin, secretary to the late M. Desmond."

Stuart gave the name he had taken. He distrusted small men; too often they had an inferiority complex that made them frightfully dangerous. This man was rather plump and very white; too white. He had a pleasant manner and sharp eyes. His hands reflected the whiteness and plumpness of his face.

"My schooner is in the cove," Stuart went on. "As I have a matter of business to discuss with Mile. Desmond, I took this occasion of stopping in. The news of her father's death came to me at Diego Suarez. It must have been a terrible shock to you all."

"Ah, m'sieu, you do not realize what a shock!" exclaimed Mandrin. He came closer, flung a glance at the doorway and hall, and lowered his voice. His penetrating dark eyes rested on the face of Stuart as he spoke.

"To her, m'sieu, above all. That is why the yacht has gone to Nosi Be—to fetch a doctor from there. The poor young lady! You should have seen her before, m'sieu, to realize the frightful change. Last night she was desperately ill. I have not yet inquired this morning; I do not know whether her maid is about or not. There has been sickness, and most of the natives have been sent to the village at the other end of the island. The work has all been stopped."

"What work?" Stuart asked in his direct fashion.

"Ylang-ylang extract—the base of perfumes. That is the big industry in this part of the world, m'sieu. It is what we in the island do."

"What's wrong with the young lady?"

Mandrin gestured vaguely. This directness was obviously disconcerting. "Grief, m'sieu. It has—must I say it?—most unhappily affected her both in mind and body. One must be extremely careful what is said. Now, if m'sieu has a matter of business to discuss, it were best handled with me. I have assumed charge of affairs for the moment, under the will of the late M. Desmond."

"I see," said Stuart, regarding the man attentively. "But this is not strictly business. It is a message from a man at Diego Suarez and it will give her very happy news. However, you spoke of sickness. What sort of sickness?"

MANDRIN thrust his head forward a little, and his eyes

rolled.

"Must I tell you, m'sieu? That is another reason we have sent for a doctor. Men have died, among the workers. I do not know much about these things, but some say that it is the plague. And if that is so, we shall have trouble. But you will excuse me, m'sieu? I must go and inquire about the young lady. When you talk with her, be very careful, I pray you, not to say anything that will cause her worry or concentration. Allow me to have some coffee sent you while you wait."

"Thank you," said Stuart, and produced his cigarettes. Mandrin bowed and left the room, plump, stepping softly, deferential and humble.

"Her head, eh? The damned liar!" thought Stuart. "Thank Heaven I met her, or I'd be tempted to believe him. And thank Heaven poor Eben told me the truth about this rat! Trying to scare me off, eh? He's a sharp one."

Mention of plague, that scourge of eastern seas and lands, would have frightened off nine seamen out of ten.

Not from fear of death, but fear of quarantine, merciless and rigid weeks of it, passed in the next hot and stinking port they might reach. Sent the yacht for a doctor, eh? That was just rubbing it in. What was the fellow's game, then? Was he really trying to get the girl for himself, as Eben had said flatly? Nonsense. A worm does not mate with a star—and yet, who knows but the worm has ambitions?

The grim run of Stuart's thoughts was broken by the entry of the same servant who had admitted him, a Hova or Sakalava from the mainland. He brought a tray oh which was a gorgeous silver coffee service, and poured a large cup of steaming black Nosi Be coffee. When Stuart questioned him, the man merely shook his head and left the room in silence.

Stuart glanced around the room. On the center table was a huge vase of scarlet hibiscus blossoms, evidently picked that morning. He emptied his cup into the vase and then lit a cigarette.

Before he had finished it, Mandrin reappeared, now clad in whites which lent his plump countenance a ghastly pallor.

"Mademoiselle is descending," he announced, then came forward and spoke softly. "And remember, m'sieu, I pray you remember my warning!"

Stuart nodded reassuringly and turned to the door as Felice Desmond entered. And in this moment he had the shock of his life.

The same girl he had met, yes, now wearing a mourning gown of gossamer black—yet not the same. The fine keen eyes were dulled and listless, the lips drooped, the face lacked life and animation. Mandrin introduced Stuart and she held out a languid hand to him.

"I am enchanted, m'sieu," she murmured in French. She was vacuous; like an idiot.

A spasm of horror seized upon Stuart.

"I UNDERSTAND that you wish to see me, m'sieu," she said listlessly, still in French.

"That is why I came."

"Oh! You came in a ship?" Her face lighted up a little.

"Certainly."

She turned to Mandrin.

"I am going down to the shore with this gentleman to look at his ship and see the ocean," she said with a sort of petulant decision. "I am going alone. We were talking last night about accounts. I forget just what it was—do you remember?"

Mandrin bowed. "Yes, mademoiselle. The household expenses for the past year."

"Oh, was that it? Well, well, have them ready for me to see when I return, and if they are not satisfactory I shall have my father speak to you when he comes back. That is all. Give me the parasol that is in the hall."

Stuart stood speechless. Mandrin stepped into the hall and returned with a sunshade, which the girl took. She went to the door. Mandrin paused at Stuart's elbow.

"Humor her, m'sieu, for the love of Heaven!" he said under his breath. "Assent to all she says. You see her condition."

"But yes," assented Stuart, and then followed the girl outside.

He offered his arm in silence, and she took it. They descended the steps and started toward the avenue of trees. Her silence weighed upon him.

Then, suddenly, her fingers squeezed his arm,

"Did you drink that coffee?"

"No." Stuart was startled by the vibrancy of her low voice.

"Good. Don't talk. Trees have ears, and we're watched."

His heart leaped. All pretense, then I She was herself, after all! Yet the whole thing was astonishing to him. It was astounding that this girl, who was mistress of the island, should act in such a manner.

"Then," he could not help saying, as they drew near the sand-swept avenue, "You know about Mandrin?"

"More than you, perhaps," she replied. "Perhaps less. Don't talk now."

The white coral sand stretched ahead, between its leafy walls of trees. Stuart stared at the sand. To his questioning surprise, there was no mark anywhere on it; his own footprints had vanished. The girl stole a sidelong glance at his face, caught his expression, and again her fingers touched and clamped on his arm.

"It's brushed, the moment any one comes," she murmured almost too softly to be heard. "That's the one thing he doesn't suspect or hinder. He thinks it a mere whim—"

She was silent again, staring empty-faced before her, the reflected sun pitiless to her vacant features under the white parasol.

Stuart walked on in bewilderment. He sensed strange, unuttered things, ugly things. It all seemed unreal, impossible. Mandrin back there in the house like a fat white scorpion—

Ahead, toward the end of the white sand strip, moved a figure with a broom. A native. He was carefully backing away, brushing out his own and Stuart's footprints. Now he halted and stood watching them, removed his hat in salute to the girl. . She gestured to the sand behind and the native walked backward again toward the house, obliterating their tracks.

PRESENTLY the mask of trees drew near, the sheds, the path to

the wharf. At the end of the wharf there was a seat of boards,

with a little roof over the top for shade. As they set foot on

the planks, the girl drew a deep breath as of tension relaxed.

She pointed to the seat ahead.

"There. That's the one place—the one place—no one can spy on us."

She looked at the schooner, without comment. They came to the seat, and she dropped on it, making room for Stuart beside her. He looked at her, and saw that her face was again that of the girl he had met. "So it's all put on?" She nodded. "Where do we begin? What brought you here?"

"Your pearls," he said. "I've brought them back. I got 'em from the thief."

"Oh! That man—that—" She broke off, shivered a little, and bit her lip.

"Stuart. He's dead now. He told me all about it. Mandrin was behind the job, wanted the pearls himself, but dared not steal them himself. Stuart did it, and double crossed Mandrin. Shall I give you the pearls now?"

"No." She gave him a queer look. "Did the police kill Stuart?"

"He was killed in a fight, by his own hand." Stuart was emotionless as bronze, but he could not keep a curious note out of his voice. The girl's blue eyes probed into him. "The police know nothing about it. I brought the pearls and the warning."

"Why didn't you keep them? They're worth a fortune."

Stuart turned and looked at her. Under his gaze a little color stole into her cheeks.

"Oh!" she said, as though he had spoken. "Oh! I understand. I didn't mean to joke that way, really. I didn't know there was any one like you alive. You're a queer man."

"I please myself."

"So do I, by Heaven! So did father!" she burst out. Fire leaped in her eyes, her voice. "I please myself! It's a good motto."

"A bad one, for happiness; that is, for a woman like you. But never mind. You please yourself—well, what does the situation here mean?"

She relaxed, drooped. "It doesn't mean that, anyhow," she said bitterly. "You had best give me the pearls, go aboard your schooner there, and skip out. I'm in a trap."

"That's why I came." Stuart offered her a cigarette, took one himself, lit a match. "Tell me. I can't comprehend it. You're wealthy, powerful, mistress here."

"No. None of those things."

She puffed at her cigarette. Stuart was shocked by her words; a calm statement of fact, so contrary to all appearances as to seem incredible. After a moment she went on quietly:

"But why should I tell you all this? You're a stranger."

"No." Stuart came to his feet, strode up and down the dock, and halted before her. He rose and fell a little on the balls of his feet—a habit he had, as though the deck were rising and falling. As she looked up at him, he met her gaze squarely.

"No. I came because you needed help. Why? Not from the goodness of my heart. Because I saw your picture in the paper, that's why." He spoke slowly, deliberately, in his calm way whose very restraint spoke so deeply. "I've gone up and down the seas a long time, pleasing myself. The time came for me to see your picture, to come here. Now that I've met you, I can say only one thing to you. I've known you a long while. Feel offended if you like; that's my whole word to you. I am at your service."

She smiled slightly, but under the black gossamer gown her bosom was rising and falling rapidly, and her blue eyes were like stars.

"Offended? I think it's wonderful," she said. "Sit down again. Words carry, and I must not speak too loudly."

Stuart obeyed.

"FATHER was like most Irishmen," she said. "A dreamer, but not

thrifty. Money meant little to him. The island, the business,

everything is mortgaged up to the hilt. A year ago, a company was

formed. I was at school in Capetown. When I got back here a few

months ago, I found Mandrin in charge of everything. My father

was not well. His stock was of no value; it was fixed so that he

could be thrown out at any moment Mandrin liked. There was only

one thing father had kept out free and clear to leave

me—those pearls. They are worth a fortune. Mandrin heard of

them too late to get his fingers on them. It is impossible to

fight that man; he is like a rubber ball half empty of air. You

push it in at one place, and a bulge comes at another place."

She tossed away her cigarette. "We came back here from Diego Suarez and I buried my father. And what happened? Three of the servants died. There was talk of plague. Most of the natives went up to the village, the work was abandoned. Mandrin sent the yacht off to Nosi Be. He and the captain understand each other. And I became sick for the first time in my life—sick in my head, as you saw me appear at the house. I could not think clearly about anything. This last time this happened, two days ago, Mandrin made love to me, though I remembered little about it. Always at night this trouble began. I figured things out. The coffee had a slight, queer taste, so I knew it was the coffee after dinner. Last night I had it served in my room, emptied it out, said I felt ill and went to bed.

"This morning, before any one was up, I slipped out. When you saw me, I had been over to the native village, trying to get hold of the one man I could trust. He was dead. I have known that I was watched, spied upon, guarded. Most of these natives fear Mandrin and obey him. I have come to have a terror of spies. That is why I have the avenue brushed—to watch for footprints of those who follow me. Eyes are watching us now. Well, that is the situation, my friend. What do you make of it?"

"A lot more than you've told me."

"True," she admitted frankly. "Some things I shrink from saying or thinking."

"Hm!" said Stuart. "In two minutes Rais Yusuf can have a boat out and at the dock. Why not come aboard this minute and leave here?"

Her eyes sparkled, the color leaped in her face.

"Oh! Yes, by all means—if you'd only been able to tell me before!"

"Well, why not? Life's more important than anything else, isn't it?"

"I suppose so. There's a box of things I must have; miniatures of my parents, a few things of my mother's. Could we go back and get them?"

Stuart thought of the pistol under his shirt, and smiled.

"Why not? It's daylight; nothing to be afraid of, certainly. No one can stop you."

"But where would you take me?"

"To the end of the world."

She met his gray eyes, and with a laugh came to her feet. Then, as she faced about toward the shore, she stopped short and shivered slightly.

"I don't know. I must have those things; but you don't understand. Something about the place brings a frantic terror to me."

"This place? Your home?"

"I hate it. I'm afraid of it. There's nothing to be afraid of, you say; that is true, and yet I'm afraid. You don't know how implicitly Mandrin is obeyed by our natives. You don't know how his frightful, inhuman brain—"

"Men are men," said Stuart calmly. "You're suffering from the effect of those attacks, or poisonings, or whatever they are. Drugs of some kind. They've left you with a deep fear of Mandrin. Well, let me handle him."

"Can you?" She looked at him with startled, questioning eyes.

Stuart smiled a little.

"Let's go up to the house," he said. "You needn't pretend any more. Here, wait one moment."

He stepped to the end of the wharf and waved his arm. A figure in the bow of the schooner made response. Stuart gestured. The figure waved again.

"All right." Stuart turned to the girl. "They understand. A boat will come ashore and wait for us. Let's go!"

They walked up the wharf toward the trees, and were lost to sight.

"WALK in, get your stuff, and walk out," Stuart said, as they neared the house. "No talk. Better let me stay with you. Don't bother about clothes."

"I can't wear these."

"Suit yourself. There's no danger."

"Wait downstairs for me, then. I'll not be five minutes."

"Better not be."

They walked in. No one was in sight. The house was silent, apparently empty. With a wave of her hand, the girl went on upstairs. Stuart turned into the reception room, lit a fresh cigarette, walked up and down.

The silence became oppressive. Stuart frowned; he felt jumpy. Had her words, her terror, infected him? Nothing to fear from that plump little rat of a Mandrin, certainly. And yet he was suddenly uneasy. At sea, he would have laid it to intuition, would have suspected something amiss. Here he was out of his element, knew not what to think. The silence, the lack of all sound, the emptiness of the house, had a queer cumulative effect on the senses.

He listened for footsteps upstairs, heard nothing, went out into the hall. He opened an opposite door, near the foot of the staircase. A dining room here, shimmering with glass and silver services; no one in sight. Stuart turned back into the hall, irresolute. A door farther along the hall swung open, and Mandrin appeared.

"Ah, captain! So you have returned," said Mandrin.

"Exactly." Stuart regarded him impassively. The smooth, plump face smiled at him.

"And do you like our island, Captain Stuart?"

"Very much——"

Stuart stopped short. The man had called him by name. The realization was like a shock to him. Mandrin smiled into his gaze.

"And you did not drink your coffee. That is too bad——"

"No palaver," snapped Stuart. "How d'you know me?"

"Your brother spoke often of you, in Diego Suarez. And you look like him." Mandrin put his head on one side, surveying Stuart. "Did you see him? Did he give you any message for me, perhaps?"

"He's dead," Stuart said. "I believe he told everything about you and the pearls. You'd better go ask the authorities."

Mandrin lifted his brows. "So? He played a double game with me."

"Are you complaining?" Stuart asked caustically. "No use. You're scotched."

Mandrin turned. "I'd better see to those reports the young lady desired. About the business, the company, everything. Poor young lady! She has forgotten just what it was she wanted to know. Are you remaining long, Captain Stuart?"

"Long enough to see you hanged, if necessary."

Mandrin rubbed his hands, stepped silently away, and was gone through the doorway whence he had come, closing the door silently behind him.

Stuart remembered the girl's simile of a rubber ball. The man was all give, no fight. Hard to battle such a creature. So Eben had talked about him, eh? Was it possible that the girl had guessed something, too? No, hardly likely. She would not have trusted him, had she known the truth. This was why he had concealed it.

Why had she not returned? What did the singular manner of Mandrin mean? Stuart glanced at the stairway, at the hall above, then impulsively dropped his cigarette into a vase of flowers and started up the stairs two at a time. His encounter with Mandrin had left him smoldering.

IN the hall above, he hesitated. Two doors stood open, one was closed. He could see no one. The closed door led to the front room. That would be hers, no doubt. He knocked at it, had no answer, tried it. The door opened to his hand. He glanced into a bedroom. Scarlet hibiscus blossoms filled a huge vase in the window. And she lay there beside the table—outstretched on the floor. A small bag, half open, was on the table by the vase.

Stuart was beside her instantly, lifting her head. Yes, she was alive. A faint, no more. The best remedy is nature's way—he extended her on the floor again, stood up, looked around. No one else here. What had caused it? She had not even changed her dress; had just put this bag on the table, half filled it with papers and other objects, then fallen over. Why? Nothing Mandrin had done; the fellow had been downstairs all the while.

An open door, a bathroom at one side. Stuart glanced at it, then looked at the windows. All closed. That was singular. The heavy odor of the flowers hung on the air. He turned, with the idea of getting water from the bathroom to revive her. Oddly enough, he could not move. His feet seemed glued to the matting on the floor. He looked down at them, put out a hand to the table; a feeling of suffocation rushed upon him. Everything whirled around—he remembered only the horrible sensation of whirling, revolving objects, as he fell.

When he wakened, he was sitting in a chair, in the same room. A heavy armchair. He was by an open window that looked out across the garden and lawn. His head was hanging on his chest. He looked down at his arms, tried to lift his hands, and could not. His head cleared; he perceived that his wrists and lower arms were securely bound to the arms of the chair with strips of toweling. And the open window—who had done all this?

His senses steadied, his eyes focused; the fresh air restored him rapidly to himself. He became aware of two figures. They were only a few feet distant, yet they took shape before him slowly. In all, several minutes passed before things ceased to whirl.

Stuart suddenly realised how he had been tricked.

Mandrin was lifting Felice Desmond to the bed, feeling her pulse. Even in his bemused condition, Stuart took note of the effortless ease with which Mandrin lifted and handled the young woman; not so much sheer strength, as agility, as knowing how. This, and his own position here, and the girl's story, showed him everything in a flashing second. How Mandrin, this soft white worm of a man, had eaten his way into Desmond's confidence and home and life, until like a worm indeed, he had digested everything. Craft and guile. These had conquered. And behind them must be an indomitable will.

It was a sickening vision.

Mandrin dropped the girl's arm and turned. With his easy, silent step he came toward Stuart, nodded amiably to him, and smiled. He reached out his arms to the big vase of hibiscus blossoms; a towel had been flung over the scarlet flowers. Mandrin picked up the vase in both hands and then paused, looking seriously at Stuart.

"You know," he said in his manner of assumed humility, "she must have received the full strength of the scent. That means she will sleep for some little time yet. Just to make things more comfortable, I will set the flowers out."

He went with them to the bathroom, and presently returned, wiping his hands.

Stuart repressed an oath. He understood now; there was some poison used, some drug, about the flowers. It was all a trap, and both he and Felice had walked into it. With a frightful effort, Stuart forced himself to repress all impulse and use his head. If he were to be himself, this horrible worm of a man would conquer him also. Nothing would win, could win, against this creature but a brain perfectly controlled, absolutely restrained. If he once lost his self-control, Stuart knew, he would play into the creature's hands.

MANDRIN came back, drew up a chair, produced a cigarette and

lit it, pulled up an ash-receiver, and then leaned back and

regarded Stuart blandly. The dark eyes in that white and hairless

face were like deep pools. They were hypnotic. Stuart thrilled a

little to the thought. Here was one secret of the man's rise to

power, beyond a question.

"You are very foolish," Mandrin said calmly, "to deliberately pit yourself against me, when you might have gained much by my friendship. Your brother told us that you were unreasonably virtuous; so I was warned against you. Now tell me the truth. Is he dead?"

"Yes," said Stuart.

"Where are the pearls?"

"Aboard my schooner. Hidden."

Mandrin nodded. Stuart had been so astonished by the question, that he blurted out the lie without thinking—consequently, without betraying that it was a lie. Evidently Mandrin had not searched him, except for weapons. The pistol, he could feel, was gone.

It is true that the pearls, hidden as they were, would attract no attention.

"Since you did not skip out with the pearls, as you might have done," mused Mandrin, "it is evident that your brother was right. Money does not tempt you. Does she tempt you?" And he gestured toward the figure on the bed.

"According to my brother, she tempts you."

"Your brother was a rascal and understood very little. She is nothing to me. It is true that I must marry her in order to legally complete my work here, remain master of the island. That is all. Perhaps we may arrange a trade."

From the words of Felice, from her hints, Stuart knew that the man lied. Here was a trap being set for him, then. He nodded coolly.

"Perhaps. The pearls are where you can't get them. How badly do you want them?"

Mandrin smiled a little at this question.

"I want them," he replied, "badly enough to offer you your life in return for them. A boat from your schooner is waiting at the wharf. I have men with rifles watching it. The morning is wearing on, Captain Stuart."

"You mean—"

"If we come to no agreement, you die. Your men die. I take your schooner."

"Bah! You would not dare."

Mandrin smiled. "You forget one thing. The body of your brother has been found, it has been guessed that you met him, took the pearls from him. I have every right to kill you and take your schooner and the pearls. True, the authorities are not in search of you except for questioning—but let the pearls be found aboard your schooner, and that is justification enough for any action I may take."

"What?" Stuart stared at him. "How do you know all this?"

"The one thing you forgot. The radio. We get daily reports from everywhere."

Mandrin slyly enjoyed his triumph. Indeed, Stuart realized that the man must be speaking the truth in this respect.

"All right." Stuart relaxed in his chair. "What do you propose?"

"Justice," said the white, plump little creature, and smacked his lips. "You will give me a letter to whoever is in charge aboard your vessel, telling him where to find the pearls; instruct him to give them to me. When I have them, I will give you a receipt for them on behalf of Mademoiselle yonder; you will be clear, you will have done your duty, you may then go your way, and take twenty thousand francs with you as a reward. If you would like an hour or two with the young lady before you leave the house—"

"No," said Stuart. "Where will I be while you get the pearls?"

"Where you are now," Mandrin said.

"Think I'd accept your word to pay the money and set me free?"

"I will pay the money to the man aboard ship who gives me the pearls."

"Hm!" grunted Stuart, and reflected. "And then poison me."

"No. I would have no reason to harm you. And I never do foolish things. You must take my word, and realize that it is backed by logic."

"True; I suppose it is," murmured Stuart. He looked down at the floor, frowning; the sun came in through the open window, striking on the hot striped matting around his feet. In places the rice-straw was worn and frayed. It must be very old.

"There is one objection," and Stuart looked up. "My mate, Rais Yusuf, speaks French and English and Swahili, but he reads only Arabic. And I cannot write Arabic."

"One of my men can write it," said Mandrin. "Does he know your signature?"

Stuart assented. Mandrin rose, went to the door, and clapped his hands. Immediately, a Malagasy servant appeared. Then there were men in the house; this was what Stuart had most desired to know.

"GET paper, ink and a brush, and come here to write a letter,"

said Mandrin. Then, as the man disappeared, he glanced at Stuart

and smiled in his sly way. "I think the young lady had better

finish her sleep in the library," he said. "She will be safe

there, and I will keep the key."

He went to the bed, lifted the girl without an effort; Stuart noted the swing of his back and shoulders. Then, quickly, Mandrin carried her out of the room, and through the open door Stuart saw him turn to the stairs with his burden, and vanish. The agility of the man was astounding.

After a moment the Malagasy appeared again. Before he was well into the room, Mandrin returned; he was not even breathing hard. Stuart eyed him with a certain respect.

"Will you dictate the letter in French, and this man will write it in Arabic, if you please?" Mandrin said, and resumed his chair.

Stuart nodded. He did not make the mistake of bargaining for what he wanted. He would ask for that casually, negligently, at the end. No taking chances with this sly rat. The Malagasy wrote in swift Arabic as Stuart began to speak:

Rais Yusuf:

The bearer of this letter is a person to whom you must give no offense. Take him aboard the ship and see that you treat him with every courtesy. Take him down to my cabin and show him how to open the secret drawer of my desk. Let him take what he will.

"You place much emphasis on the treatment to be accorded me," said Mandrin suspiciously.

Stuart shrugged slightly. "If you do not like my letter, write your own and I will sign it. This Rais Yusuf is a rough fellow who has little courtesy."

Mandrin nodded, and produced the pistol he had taken from Stuart.

"Free his right arm," he told the Malagasy, "let him sign, then bind his arm to the chair again. And do not stand between us."

The brown man obeyed. The slit towel did not bite into the skin as a cord would have done; Stuart was perfectly able to sign the letter. When he was again tied fast, he glanced at Mandrin.

"I suppose I may have a cigarette?" he asked casually.

"Of course." Mandrin produced one, came to Stuart, placed it between his lips. He struck a match and held it until the cigarette was alight. Then he turned and gave the pistol to the brown man.

"Keep watch over him until I return, and do not leave this room," he said, and flung Stuart a sly look. "Try to bribe him if you like, threaten him, say what you please. It will be of no use. If I do not return in half an hour, you will be shot. Au revoir!"

And he departed, swiftly, silently, exultantly, slamming the door behind him.

STUART puffed at his cigarette, a grim amusement in his gray eyes. One of the prime principles of prestidigitation, otherwise the art of magic, is to so center the attention of the beholders upon unimportant matters, that they miss the more important trifle which may even be obvious. Stuart was no magician, but in this case he had applied the principle with complete success. So far as Mandrin was concerned, at least. That gentleman had been too busy to do the one thing which Stuart had feared.

Turning his head, Stuart looked from the open window. He could see a portion of the green garden, and the beginning of the white avenue of coral sand. The figure of Mandrin appeared, now wearing a sun helmet, and passed from sight down the avenue.

Stuart relaxed. The moment had come. The Malagasy sat motionless in his chair by the door. His eyes were fastened upon Stuart unwinkingly, in a constant, steady gaze; his brown features showed no emotion, no intelligence. He held the pistol on his knee. A fiat, deadly little Colt. The one safety catch was off. The other one would yield to a pressure of the trigger finger, of the hand, while the weapon was fired.

Stuart glanced down at the floor as he puffed. Upon one slight motion of his lips, now depended his whole scheme of escape. He could not afford a mistake. He puffed rapidly, until the cigarette, half consumed, showed an inch-long ember of red tobacco. Then Stuart pursed his tips and let it fall to the floor. It fell exactly where he wished.

The brown man did not move.

Veiling the eager suspense in his eyes, Stuart moved in his chair a little, eased himself into the position he needed; his arms, bound to the chair, gave him a powerful fulcrum. Suddenly he saw the Malagasy's jaw fall. The man looked down; a startled expression came into his eyes.

From the worn, frayed matting, hot and dry as tinder in the sunlight, was ascending a thickening spiral of smoke. The red ember of the cigarette had caught it alight.

With a mutter, the brown man left his chair. He looked at Stuart, halted, held the pistol in his left hand, and leaning forward, extended his right hand to pick up the fallen cigarette. As though on a coiled spring, Stuart's foot shot out with terrific force. I Its boot took the hapless Malagasy squarely under the angle of the jaw.

The brown head was snapped back. A gasping groan escaped the man. The pistol fell from his hand. Then he collapsed and fell forward on his breast; but as he lay, his head was twisted queerly sideways. That frightful impact had broken his neck.

Stuart slid down, got his feet on the floor, pressed the chair back. He stood up. He was forced to lean far forward, lifting the heavy chair behind him with his bound arms.

The bed was a high, massive, ugly affair with carven panels along the sides and top in Malagasy fashion, and huge carven posts; it was solid, more solid than the very house itself. Stuart backed toward one of the corner posts, gaged his position carefully, then flung himself backwards full weight, so that the bottom brace of the chair was smashed against the carven bedpost.

He toppled to the floor with the ungainly chair above him. Awkwardly, he gained his feet and repeated the action. This time, the bottom rung of the chair splintered. The bedpost remained wedged between the two hind legs of the chair. Stuart threw all his weight first to one side, then the other. Desperately, he redoubled his exertions. With a rending crash, one of the rear legs gave way.

THE curl of smoke from the matting had become a spreading glow

which sent up increasing quantities of smoke. A sickening smell

of scorched flesh filled the air; but the Malagasy was past

feeling the fiery glow that touched him. A tongue of flame licked

up toward one of the window draperies.

Stuart smashed the chair against the solid bedpost, again and again, still forced to stoop under the burden. Sweat poured from him. Twice he fell to his knees, but rose again to repeat his efforts. The second hind leg smashed out, then one of the front legs. With a tremendous effort, his whole body arched like a bow, he forced the seat out of the chair.

The back and arms still bound him fast, but now he could stand erect.

Again he hammered at the bedpost with the carven wood constraining him. Flames were licking across the floor, were mounting along the window drapes. Panting, exhausted, every nerve and muscle at tension, Stuart got the chair-back hooked about the bedpost, then pulled one of the arms from its socket. That was the end.

Trembling, streaming with sweat, he freed his left arm, then his right. A swift step, and he picked up the fallen pistol, and slipped it back into the holster under his shirt.

Flames were all about the table now. Unhurried, Stuart went to it, caught at the open bag there, and lifted it back from the smoke to the bed. From the half-filled handbag he stuffed everything into his jacket pockets, regardless of the bulge. This done, he went to the door, opened it, stepped into the hall. A rush of smoke poured after him. He closed the door and turned to the stairs.

On the landing he paused, suddenly startled. There against the wall hung a huge German barometer. Stuart glanced automatically at it and froze. A low whistle escaped him. The glass was falling. The needle had swung over to "Storm." If the thing were working, then there was no time to lose. He knew all too well the frightful rapidity with which weather comes up in the Mozambique Channel. Fair as was the day, an hour hence might see a hurricane raging; and the schooner was in no position to ride out a blow where she lay, or anywhere about here.

Stuart went on, seeing no one, but hearing a rising crackle of flames from the chamber he had left.

The library, he guessed, must be the room from which Mandrin had come, below the staircase. Gaining the lower hall, Stuart passed rapidly back to this door and tried it. Locked.

"Felice!" He ventured a call, but had no response. He drew back and flung himself against the door. It held, but promised to give way at another attempt. As Stuart drew back again, a native appeared, darting out of the reception room—a brown man who held a rifle. At sight of Stuart he halted and jerked up his weapon, a cry bursting from him.

Stuart whipped out his pistol and the Malagasy pitched sideways. The rifle exploded, the bullet going into the ceiling. With a leap, Stuart hurled himself at the door. It burst inward beneath his weight and he went rolling, then came to his feet. The room was dark, but for the light from the door. Shutters over the two windows were apparently locked. On a couch close at hand lay Felice Desmond, her eyes closed.

From any other room, Stuart knew, the gardens could be reached by means of the long windows. Not here, however. He caught up the girl in his arms, and grunted to think of how easily Mandrin had handled her weight. He bore her out into the hall, saw no one but the native he had shot, and turned back toward the next room. To flee by the front way and the avenue of coral sand would be suicide.

THE door opened to his hand. A sunlit room, a laboratory of some kind, no doubt for work with the perfume bases which formed the island's industry. Stuart went to one of the windows, laid the girl on the floor, and another instant saw the window and screen swung open. The ground was only a foot below the window level.

As Stuart bent to lift her, Felice opened her eyes. She looked up, saw his face close, and a smile touched her lips. Stuart caught her up in his arms and laughed.

"Come along. No questions. Put your arms about my neck."

She obeyed, drowsily. Stuart stepped out from the window and carried her across a stretch of flower-beds to a hedge. Beyond were trees. He smashed through the hedge. From somewhere in the house, from somewhere outside, were rising shrill yells. A trail of smoke suddenly burst upward from the front of the house.

The trees closed them in, shut out everything. Then, feeling safe, Stuart set her down carefully and stood up. She came to one elbow, staring at him.

"What has happened? What are we doing here?"

He smiled a little, lit a cigarette, and sat down beside her.

"You were right to fear Mandrin. Poison by inhalation; the flowers, the hibiscus blossoms. Not poison, perhaps, but some drug. No matter. He got us. I've brought you here, and my pockets are stuffed with everything in that bag you were packing. Your house is afire. It's our one chance. While it blazes, can you guide me through these thick trees to the cove? We can't go by the avenue. Are you up to it?"

He was delighted by the swift comprehension in her eyes. She must have slept off the drug. Then she sat up, the old eager decision in her face, her blue eyes alight.

"Yes, yes; of course I can. Oh, what fools we were to come back for anything? Where is Mandrin now?"

She glanced at him half fearfully. Stuart's gray eyes wrinkled amusedly.

"Waiting for me. I agreed to give him the pearls for my liberty. He went aboard to get them from my schooner, taking a letter to my mate, Rais Yusuf. That old rascal is shrewd."

"Then the pearls are—why, I thought you had them with you?"

"I have, but Mandrin didn't suspect it. I told Rais Yusuf to show him the secret drawer in my desk. I have no desk, no secret drawer, and Yusuf is well aware of it. I did not tell him to let Mandrin go ashore again—and he won't. Old Yusuf understands me."

"Oh! Then he's aboard your schooner?" she asked, and Stuart nodded. "In that case, Captain Stuart, look out for your schooner!"

Stuart's brows lifted. "You know my name?"

"Of course. I knew it from the first." She broke into a little laugh of amusement at his expression. "Your brother had spoken of you. Then there is a resemblance; not a likeness, though. You're at the other end of the earth from him. Why didn't you say who you were?"

"I thought you might not trust me," Stuart said simply. Her eyes warmed upon him.

"Do you think any one who exchanged words and looks with you, would not trust you? But what are you smiling about?"

"Mandrin," he replied. "I just recollected that he promised to leave twenty thousand francs aboard the schooner. If he took that money with him, Yusuf will have it by this time. I know that old thief. Well, so much the better! The money will belong to you."

While he spoke, Felice came to her feet, listening to the sounds that reached them.

"We had better go," she said. "I'm all right."

"Good. Yes, we're going to have a bad blow, if your barometer tells the truth. Better make time. Can you walk now?"

She nodded. For the first few steps she was unsteady on her feet, but the effects of the drug passed swiftly, and she was soon quite herself again. A crackling roar of flames reached through the trees, and above the trees was visible a mounting plume of black smoke and fiery particles. Men were shouting in wild uproar.

MANY imperceptible paths, no doubt made by bare feet, wound

among the trees. Felice treaded them swiftly, surely, never

pausing. The shouts and yells, the crackling flames, fell dim

behind them. Presently the girl paused, and gave Stuart a

look.

"They are calling for Mandrin," she said. "There may be men on the wharf. He has brought natives from the mainland who obey him implicitly; he has given them arms."

"Go ahead," Stuart said calmly. Her eyes widened a little.

"Do you always go ahead?"

"In case of doubt, yes," and he smiled. "One never gets anywhere from fear of making mistakes."

She shrugged lightly and went on. Stuart followed her closely. After a time the glitter of the sea appeared through the trees, then the two of them came out abruptly on the beach, just to one side of the wharf and sheds.

Stuart laid his hand on the girl's arm, checking her, halting her. His gray eyes flitted from wharf to sky, and back again.

A haze thinned the fierceness of the noonday sun. The schooner rocked at her buoy to a long, slow swell. There was a slight offshore breeze, but a mass of cloud was piling high into the southern sky.

Toward the end of the wharf stood two stalwart Malagasies. They carried rifles and were directing frantic shouts at the schooner, where no one appeared. Alongside the wharf floated the boat, with Rais Yusuf lolling in the sternsheets. He and the oarsmen appeared sleepy, indolent, and were exchanging repartee with the two natives above.

"Come along. No one else in sight here," said Stuart. He glanced at the sky again. "We've no more than twenty minutes before the blow hits us. We must haul off."

"But those two natives there! If you don't get the schooner away—"

"We won't by talking about it."

He stepped out briskly toward the wharf. Rais Yusuf saw the two figures and straightened up, then rose and went forward to the bow of the boat, and stood there. The Malagasies, who were facing the schooner, did not see Stuart and the girl until they were coming out along the wharf. Then they both whirled around, stared, hitched up their rifles.

Felice uttered an angry order. They shook their heads.

"Go back," said one of them in French, and lifted his rifle. "Go back, do you hear?"

Stuart put hand to pistol, then halted. The boat was floating down the side of the wharf. Rats Yusuf moved; his teeth flashed in a laugh, and the sun glinted on his knife as he struck upward. His knife plunged through the leg of the Malagasy who had spoken, and with a yell the man leaped aside, lost balance, fell into the water.

The other brown man flung up his rifle, aiming at Stuart, but the pistol spoke first. To the two sharp reports, the man whirled around and fell half over the edge, then slipped off and was gone. Already the first brown man was on his feet, up to his neck in the water, and Rais Yusuf stood laughing at him.

"No time to lose, effendi," he cried to Stuart. "The little man is safe locked in the cabin. The glass is falling."

Stuart stepped down into the stern-sheets, gave his hand to Felice, and as she joined him the men dipped their oars.

They were all grinning widely, and flung barbed words at the Malagasy who stood there in the water, cursing them.

Felice touched Stuart's arm. He met her wide, anxious eyes.

"What will you do—what will Mandrin do?" she breathed. "You'll not shoot him?"

"Do you care?"

"No. But somehow I have a horror of seeing him perish—I would never forget it——"

"I understand." Stuart nodded. "He's poisonous. All right. Rais Yusuf, you'll take charge at once, get the boat in, stand out to sea. Or—wait! Leave the boat overside; make it fast to the buoy, leave it. We always have the other one."

Rais Yusuf assented calmly.

A moment later they swept in under the ladder of the schooner. Stuart mounted first, helped Felice to the deck, pointed to the scrap of awning and the chair in the stern.

"Wait there," he said, and headed for the companionway. He flung out his arm to the column of smoke and flame ashore. "Your house is burning."

She shivered a little, flung a glance ashore, then smiled.

AS Stuart passed down the ladder, he understood perfectly how the girl felt about this man locked in below.

He felt the same thing now; as though he descended to meet some loathsome reptile. All his will power drove him down that ladder. He shrank terribly from facing Mandrin. Not from fear. Some quality of the man brought prickles to the spine.

At the foot of the ladder, Stuart turned to unlock the door of his cabin; the key was on the outside. He caught out his pistol and held it ready. Would this creature have turned into a wild beast, seeking only to rend his enemy? He unlocked the door and thrust it open, then stood back.

"Come along, Mandrin."

Mandrin emerged, empty-handed, the dark eyes in his white face like pools of evil. Stuart gestured with the pistol.

"Up the ladder, and move sharp. We're leaving. The boat's waiting for you—go ashore and be damned to you."

Mandrin stopped short and glared at him. The man's fingers clenched and unclenched; in his gaze was a hatred unutterable, beyond all words. Under the icy gray eyes, he turned to the ladder in silence.

Face to face with the man, Stuart experienced a sudden revulsion of feeling. What nonsense, to fear this little creature! He stepped forward, as Mandrin reached the ladder and started up. He followed the other closely.

Halfway to the deck, Mandrin's foot slipped. He did not turn around. He did not look back. His foot slipped, that was all. Stuart saw it slip—then the other was on top of him, falling backward, knocking him headlong to the bottom of the ladder and crashing down with him. It all happened in a split second of time. As Stuart tried to fire, he struck the deck with terrific force and the pistol flew from his hand.

Then Mandrin was upon him, and a knife glittered.

Stuart felt the steel drive into him. Strong as he was, against the rippling muscles of this creature he was like a child. He tried vainly to fight; his blows had no effect. He tried to reach his feet. With one hand Mandrin held him down—a hand like a vise. Again the knife glinted and struck down, drove home. Writhing, thrashing about, Stuart wrenched it out of the man's hand. Then Mandrin was gone. Up the ladder with a leap, an incredible leap like that of an animal.

As he lay, Stuart's fingers closed on the lost pistol. He jerked it up, fired at the shape above. Just as Mandrin reached the deck, the shot rang out. It was answered by a wild cry. Stuart gained his feet and threw himself at the ladder. He scrambled up, caught one glimpse of Mandrin at the rail. The schooner had just cast off, the canvas was fluttering out, she was turning, heeling over to the breeze.

Stuart flung up his weapon and fired again—too late. Mandrin was gone in a plunging dive that carried him out of sight.

From Rais Yusuf broke a wild yell of fury and dismay. Felice came running, caught Stuart as he staggered. Blood was pouring down his side, his right leg. The pistol fell out of his hand. In the air was a keen humming, a singing whistle; the whole southern sky, up to the zenith, was a fury of cloud. Barely in time, the schooner was away. Thirty seconds and she would be able to clear the headland.

Stuart looked down. He shook loose the girl's hold, rid himself of his coat; it was pinned to him. The knife had gone through the side—through the pocket, stuffed with papers and the cigarette tin of pearls. He laughed and pulled the knife point from his hip. He threw it and the coat down the companionway to safety.

Then he keeled over with a little sigh, and Felice caught him.

The roar of Rais Yusuf brought a brown man to the wheel. The old Arab rushed to the side of Stuart, tore away his shirt, laid bare the two slashes in his side. He grunted in relief, then lifted Stuart in his arms and carried the limp figure down the ladder and on into the cabin. When he had laid Stuart in his berth, he turned to find Felice at his side.

"You here? The hurts are nothing. He must be bandaged and kept quiet—"

"Leave that to me," she said. Rais Yusuf pawed his beard doubtfully.

"You? But you arc a woman. And this is work to be done carefully."

"Get out!" Anger flamed suddenly in her eyes. "He told you to take charge of the ship; do it, then. Get back to your post before I call the men to whip you on deck!"

Rais Yusuf grinned delightedly and stalked out. At the door he turned as though to speak, but checked himself abruptly as he saw the girl lean over Stuart, touching his cheek with furtive, tender fingers. He closed the door and chuckled in his beard, then went for the deck with a rush, and slammed shut the companion hatches.

"By Allah, there is a woman fit for him!" he cried gustily, and looked back at the boat.

Mandrin's figure had reached it. Mandrin had put up both hands to the gunwale, drawing himself up. He hung poised there for a long moment. It was queer that his amazing strength was not equal to that little lift. Then, as he hung thus, half out of the water, a growing splotch of water-thinned crimson widened out between his shoulders. Stuart's first bullet had not missed.

Fascinated, Rais Yusuf watched, and saw the two white hands suddenly lose their grip. The figure of Mandrin plunged down and did not come up again.

Rais Yusuf spat over the side—then turned and rushed for the wheel as the hissing line of wind and foam struck upon diem. And the whole shape of Amber Island was blotted out in an instant, forever.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.