RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Blue Book Magazine, Feb 1933, with "Three-Piece Dollar"

The manager of a tin-mine in the interior of China runs

into a strange adventure—by the able author of

"The Bamboo Jewel," "Madagascar Gold" and many others.

ERSKINE was one of those men who—even as you and I—are not what they seem.

He had been sent up from Singapore to manage the Gomorrah mine; he knew tin-mining, spoke Malay and Chinese, and looked just the sort of man to be imposed upon. He was small, wore spectacles; his sandy hair was usually mussed, his freckled nose turned up a bit, and he had a serious, practical expression. The mine was three days north of Yunnan City, and he had no objection to being stuck up there in the hills by himself with the mine and its village of Chinese workmen.

Erskine was unmarried, said that he had no time to waste on social affairs, and disproved it by having a gorgeous time each month-end when he came down to Yunnan City. The foreign colony liked him. It developed that he had the most amazing knowledge about all sorts of things, and he could dance superbly. Also, he began to enlarge the production of the mine before he had been there three months; so all in all, he was a distinct acquisition, at least, among those who knew him well.

Calverly did not know him well, of course. The big, drawling, handsome blond Englishman turned up in Yunnan City one day, accompanied by the Vicomte de Plancy, a very polite, sleek little man with spiky black mustache and sloe eyes, who drove their Citroen car. They had unkind things to say of the boasted highway north from the Tonkin border and the car was laid up for repairs.

Since Plancy was an authentic vicomte and Calverly a pleasant and briefly plausible fellow, and Yunnan had the reputation of being the most hospitable of all Chinese cities, things went well. The two of them put up at the Hotel Terminus and were still there a fortnight later when Erskine arrived for his regular monthly visit. Calverly was at the desk when he strode in and asked for his regular room.

"Beg pardon," said Calverly, "You're not Erskine of the Gomorrah Mine, by any chance?"

"The same, the same," said Erskine, peering through his spectacles. Calverly put out his hand, eagerness beaming in his face.

"Calverly, J.R.C. Calverly. My dear fellow, you're the one man up here I've been most anxious to meet! Heard of you at Singapore and at Trengganu. You were with the Consolidated people down there, eh? They told me you were one of the best tin experts in the field. I've a letter of introduction to you, somewhere in my luggage. We'll have it out."

Erskine was embarrassed by this flattery. He was tired and dirty and hungry, and had a sack of mail to run through; he arranged to dine at the club with Calverly, and then went to his room. Later, when he had shaved and bathed, he was sitting clad in spectacles and shorts, glancing over the stack of letters, when M. de Mersuay, whose position corresponded to that of freight-agent for the French railroad running up from Haiphong, dropped in to see him about tin shipments. When their business was over, Erskine inquired about Calverly.

"An amiable gentleman," said Mersuay, fingering his chin-tuft. "With him came the Vicomte de Plancy, of the lesser nobility. I do not know their business here, but it is said that they are interested in mining concessions."

"Plancy is well known?" inquired Erskine.

"Of a certainty. He resigned recently from the Annamese Customs; I do not the know the reasons. He is not, perhaps, too scrupulous in minor details."

Mersuay hesitated. "Still, who knows? Gossip amounts to nothing. One must form his own conclusions."

"Exactly," said Erskine, ruffling up his sandy hair.

"How long shall you be with us this trip?" inquired the other.

"A week at least," said Erskine. "Who knows?"

He dined that evening with Calverly, and met the Vicomte, who was also at the club.

DURING the three days following, Erskine saw a good deal of

both Calverly and Plancy, who opened out their affairs to him

very frankly.

It was true that they had a mining concession in mind, and were thinking of taking over a silver mine in the hills east of the city. Erskine was only too glad to impart any information at his command, and they questioned him at length in regard to the various details of mine-operation under the existing and constantly changing laws promulgated by the Yunnan governor, the supply of native labor, and so on.

On the fourth day, while Erskine was lunching at the club with Doctor Aintree, talking hospital procedure and enjoying the view over the lake, Calverly dropped in upon them and plumped himself down at their table. He was in high excitement.

"Everything's arranged—the red tape and all that rot," he announced, beaming. "The governor approved the arrangements this morning. I say, Erskine! Plancy and I are putting everything we can raise into this concession, you know. I've had a bit of experience, and so has he, and we can carry on once we're started; but getting started is the rub. I'd jolly well hate to get off on the wrong foot, and you're the very man to help us out."

"Yes?" said Erskine. "In what way?"

"Advice," responded Calverly. "I'd like frightfully, old chap, to get your opinion of the ground we have in mind."

"Afraid my opinion isn't worth much," said Erskine, looking embarrassed.

"Nonsense! You're the one expert up here. You know, this Black Dragon mine is a long day's ride from here, up toward Sinfan- chow. With the preliminaries settled, we're going up day after tomorrow to take a look at the property before signing the papers. We've got guides, and we'll take along a few chop-boxes and a couple of boys. What about going with us? You can name your own fee and all that; it'll take two days of your time, more likely three, as we'd have to be there the best part of a day."

Erskine ran his fingers through his unruly sandy hair.

"I don't know, Calverly," he said slowly. "Afraid I couldn't take the responsibility of such a thing. If anything went wrong—"

"Bosh!" struck in Doctor Aintree, who liked Erskine and knew his abilities. "Weren't you telling me that you'd put in two years up in the Honan silver district? Ye know verra well, John Erskine, that ye've not your equal as a mineralogist in all south China! It'll do no harm to give an opinion."

"Precisely!" exclaimed Calverly eagerly. "You'd have no responsibility, old chap; an opinion on the silver veins is what we're after. Plancy would take my say-so, but we should have an unbiased verdict from an outsider. Don't be moldy, Erskine. Say yes, like a good fellow!"

Erskine smiled in his bashful, awkward way.

"Well, I suppose so," he said. "But I'd not be charging any fee, Calverly; that's out of the question. I couldn't draw my salary and be doing odd jobs on the side, you know."

The big Englishman clapped him heartily on the shoulder.

"Right! I say, you're a good egg, and we'll appreciate it, let me tell you! Besides, you speak Chinese far better than I; these local dialects are the devil and all! Plancy can't waggle 'em worth a farthing, and we can't trust these native interpreters."

"To tell the truth," confessed Erskine, his eyes twinkling, "I've heard about that Black Dragon mine and have meant to take a look at it for my own people, but I never got around to it. Think you can trust me?"

Calverly looked at him and grinned, as he put forth a hand.

"Absolutely. It's a bargain. Shake!"

Erskine shook hands, looking a bit confused, and Calverly jovially called for a drink all around to celebrate.

"If you change your mind about the fee, don't hesitate to say so!" he exclaimed. "I'll drop in on you in the morning, as soon as we've perfected arrangements. I understand we can use horses, as the trails are good. Deuced good thing. I abominate these mountain mules!"

He departed, having an engagement to lunch with others, and Erskine gave the Doctor a whimsical glance.

"There I go," he murmured. "Three days among the hills, instead of enjoying life here! And if they buy the property and go bust, they'll blame me."

"Not a bit of it," said Aintree stoutly. "Good sportsmen, both of them. I've heard the Vicomte well spoken of; he's a polo enthusiast, and that means a good deal. I can't say I cotton to Calverly particularly, but don't ye borrow trouble. Be frank, and shame the devil!"

Erskine laughed, and reverted to hospital topics.

ON the following morning Calverly and Plancy found him in his

room. The Vicomte was a vivacious and engaging companion, always

very courteous, but full of high spirits; he had a heavy Bourbon

jaw, and his black eyes were always flitting about. He expressed

his delight that Erskine had consented to give an opinion, in

well-chosen terms that left Erskine looking more awkward than

ever.

"That's quite all right," he rejoined. "What about arrangements?"

"All settled," boomed big Calverly. "There's no rest-house up there, but we'll put up at an abandoned hill-temple a mile or so from the location. I say, Erskine—no bandits around here, I suppose?"

Erskine shrugged. "Off and on, yes. They don't bother foreigners, though; no anti-foreign feeling in Yunnan. And the Government has things pretty well in hand here. We have about the safest province in China, I understand."

"Hello!" Calverly looked at the table where Erskine had been at work. "Experiments? You're not drinking spirits I hope? Not neat, at any rate."

Erskine glanced at the bottle of alcohol, and laughed.

"No," he said with a whimsical expression. "I always seem to get stuck, somehow. Last night it was bad dollars—at least, I think they're bad. I was about to try 'em out. Would it interest you? Here, look at them. The chops are Canton, but Canton's quite a way off."

He picked up two Mexican dollars and the other men drew up to examine the coins. Owing to the prevalence of bad money in China, silver dollars are usually stamped with the chop of money- changers, the chop serving as guarantee. In Canton, this chop is applied with a steel die, the use of which, after a time, defaces the coin itself and changes its shape.

"What makes you think these are bad?" asked the Vicomte with interest. "They look good enough."

"They don't ring true," said Erskine, pouring alcohol into a shallow dish. "Did you ever hear of three-piece dollars? I fancy we have a couple of them right here. Drop in yours, Calverly."

The Englishman dropped the dollar from his hand into the dish. Erskine struck a match and touched off the alcohol.

"It's almost incredible to what lengths of labor and time these Chinese will go, for the sake of a few cents' worth of silver," he said, his eyes sparkling with animation as he watched the bluish flame dancing up. "A striking commentary on the cheapness of labor, too. Wait till I get a glass of water—that stuff will be too hot to touch."

He obtained the water, and when the flame of the alcohol died out, poured in the water and cooled off the coin. He picked it up, and it fell apart.

"I say!" exclaimed Calverly with interest. "Three-piece dollars, eh! Good name for it, too—"

"Yes, I always get stuck," said Erskine plaintively, but with a chuckle none the less. "Here you are. Look, Plancy! The face of the dollar has been removed, the silver scooped out and replaced with brass to give it the proper weight; then the coin was soldered together again. Apparently pure silver and correct weight. Melt it apart, and you have two faces of silver, and a neat little chunk of brass. Oddly enough, the chunk of brass is the only one of the three pieces that isn't false—there's a paradox for you!"

His visitors gone, Erskine returned, picked up the "three- piece dollar" and inspected the fragments with a slow smile, as though he saw more in them than two hollow faces of silver and a little chunk of brass.

THE three got off in the morning, taking along a guide, two

servants, and a couple of spare horses loaded with chop-boxes of

provisions. All three Chinese had been furnished by the hotel and

were reliable, steady fellows.

Until noon they followed the main caravan highway toward Sinfan, then struck off by a narrower but fair enough road into the hills. Erskine, once afield, lost his shyness and became a different person, talking volubly, interested in everything around. Neither he nor the Vicomte carried rifles, but Calverly had borrowed a shotgun from the British consul, in the hope of knocking over a pheasant or two. An hour after they branched from the highway, he bagged a brace without leaving the road, and was the happiest of men in consequence.

Erskine found that the Vicomte was a true Frenchman, on the head of business; he had a shrewd grasp of detail, boasted of his influence with the colonial administration, and was an open admirer of the Gomorrah mine. His knowledge of it, indeed, somewhat surprised Erskine. True, the mine was owned by a Singapore syndicate, and it was an exceedingly wealthy property, but Plancy had a more intimate acquaintance with its earnings and reports than Erskine himself. Which, of course, merely went to prove his business acumen.

The afternoon was far advanced when they came up the winding valley trail leading to the Hei Lung, or Black Dragon, mine and village. Their guide halted at a fork in the trail, and informed them that the main road went on to the village and mine, the right fork going directly to the temple and spring a mile from it.

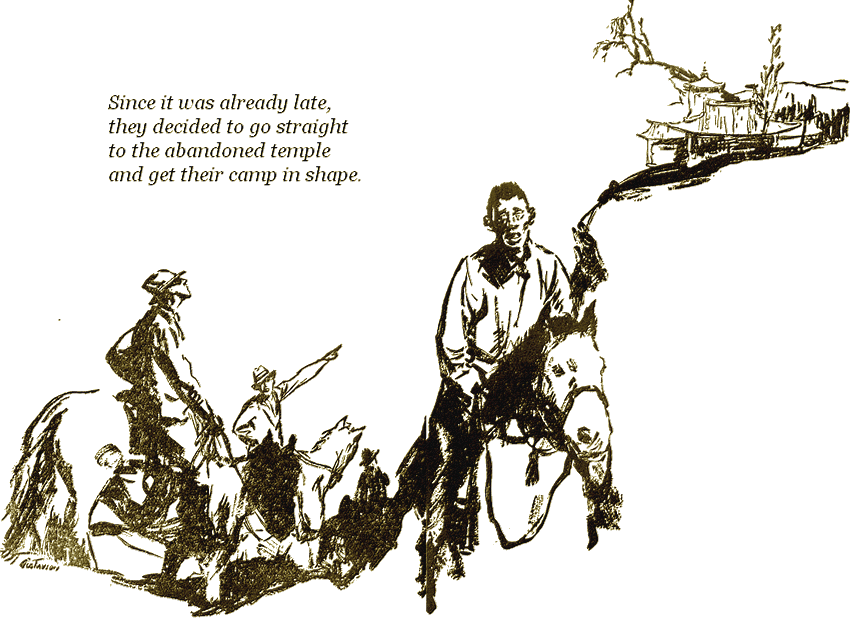

Since it was already late, and they must make habitable the abandoned temple, it was decided to go straight to the latter and get their camp in shape, and inspect the mining property in the morning. Twenty minutes later they sighted their destination.

THE beauty of the site was astonishing. In the depth of a

hillside nook whence gushed forth a bubbling, plunging stream of

the clearest water, an ancient and half-ruined temple was

overhung by the trees. The graceful arched approach and stone-

paved terrace, with guardian lanterns of stone, were perfect. The

building behind was largely ruined and the images of the gods had

departed, but a portion of the central hall could be cleared in

short order, and the roof-tiles were in place.

All hands fell to work, the horses being hobbled to graze behind the temple; the guide departed for the village, where he had friends, and the two servants put up the folding table in the terrace and laid out the evening meal. It was ready by the time the three had cleared enough of the central hall to hold their blankets; there were no reptiles or insects of any sort, and when finished, they enjoyed a quick bath in the crystal-clear waters of the spring, which was famed for its purity. They sat down to supper, in the sunset, feeling like new men.

Afterward, when the cold stars had appeared overhead and the chill mountain air made their blazing fire a cheery and delightful thing, they sat about the blaze and smoked, and became human as men will at such moments. When, later, he looked back at these hours and recalled the jovial fellowship of Calverly, and the urbane, half-cynical philosophy voiced by Plancy, and their rather intimate confidences, Erskine could not but feel a bewildered wonder at the intricacies of life, and the possibilities of human nature.

The three at last abandoned the dying fire to the two servants, and rolled up in their blankets. Erskine lay awake for a long while, a little resentful at coming here to this uncomfortable bed on the cold stones, when the village would at least have afforded them a house and more creature comforts; for Erskine did not enjoy roughing it in the least. Also, the hearty snores of Calverly disturbed him.

The temple was built in the ancient fashion, exactly as skyscrapers of today are built—of great ironwood beams in skeleton structure, filled in and masked by stone walls. The stones, on the interior, were dotted here and there by phosphorescent fungi; and Erskine eyed these as he lay in the darkness. Various Chinese legends recurred to his mind in regard to such lichens and their supernatural and baleful attributes. After a bit, without disturbing his companions, he rose and slipped outside. Lighting a cigarette, he gazed out across the dark starlit hills until his uneasiness had worn away and he was chilled; then, returning to his blankets gratefully, he rolled up, and was asleep in five minutes.

WHEN he wakened, a blinding ray of light was striking directly

in his eyes. He came to one elbow, blinking. The ray of light

came from an electric torch; outside, he caught a shrill

chattering of frightened Chinese voices, silenced by a curt,

harsh command. Then he realized that he was being kicked, and he

sat up hurriedly.

"What the devil!" he exclaimed. "It isn't daylight yet—"

His voice died out. At one side he saw Calverly and the Vicomte standing, their hands in the air. The flashlight was held by a figure standing over him, who reached forward and patted his pockets, glanced at his belt, found no weapon and stepped back a pace.

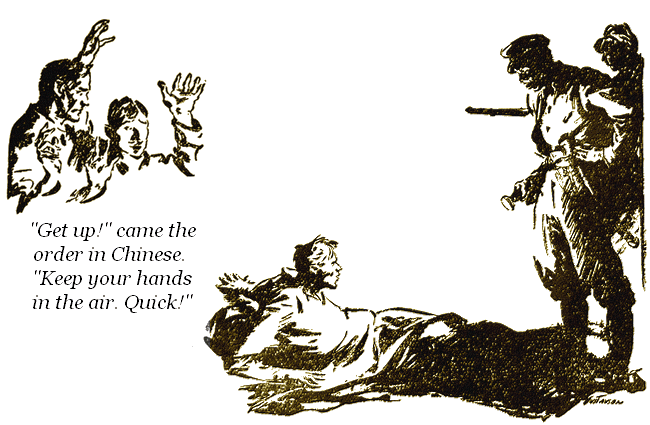

"Get up!" came the order in Chinese. "Join these other two foreign devils. Keep your hands in the air. Quick!"

"Better toe the line, old chap," came the voice of Calverly. "This fellow seems to mean business, and I fancy he's got our boys attended to, outside. Seems to have a nasty temper, the blighter! Feels as though he'd kicked a couple of my ribs loose."

Indeed, blood showed on the lips of Calverly; evidently he had offered resistance. Erskine, who had slept without removing anything but his boots, pulled them on and then struggled to his feet, still bewildered. Other men came into the room, bearing lanterns. Like their leader, they were Chinese, and wore ragged khaki uniforms. In a flash, Erskine realized they must be bandits, probably soldiers who had deserted and taken to the hills.

The leader, a squat, broad-faced man, gave a curt command.

"Tie their hands behind them."

The others, four in all, obeyed, one keeping his rifle trained on the whites, while his comrades bound their arms together. Erskine was wide awake by this time, and made urgent protest to the leader.

"You will be severely punished for this outrage—"

One of the men struck him across the mouth with a curt order for silence. The Vicomte shrugged, and Calverly grinned in resignation.

From outside came a wailing cry, then a shriek of agony, followed by harsh voices. The two servants were dragged into the room by other men, and the leader turned to them and began an interrogation. Bleeding, terrorized, the servants answered his questions without reserve, telling who Erskine was, and who the others were. The leader gave an order, and the two were dragged out.

Then he turned to the three whites, strode up to them, stared at them with hard and glittering eyes.

"I am Chang Chin," he said calmly, speaking slowly, that they might understand perfectly. "I heard that you were coming to look at the Black Dragon mine. You expect to buy it. However, I do not like foreign devils. Two of you came here to buy the mine; instead, you shall buy freedom. One of you already has a rich mine; it shall buy his freedom. If not, you shall die. Do you understand?"

"Well enough," answered Erskine, at a nod from the Englishman. "You are a bandit, I suppose? None of us are rich men—"

"I am not here to argue," cut in Chang Chin with level finality, "but to give you my orders. You,"—and he thrust his finger at Erskine—"will remain here. One of the others will remain. The third will go to Yunnan City in half an hour. He will reach there in the afternoon. On the next day at noon, he will come alone, with the money, to the point where the road for this place leaves the highway. He will bring twenty thousand dollars in bank-notes for the freedom of his companion, and another twenty thousand for the freedom of this man who mines tin. My men will be on the watch. If he does not come alone, if soldiers leave Yunnan City, the two who remain will be killed at once. We shall not stay here, in any case, so it would be very foolish to send soldiers; I would not be found, and the other two would be killed. And remember, I mean gold dollars, not Mexican dollars."

"You will be hunted down later," said Erskine. "You cannot escape. The whole province will be roused against you; the frontiers will be closed."

Chang Chin regarded him fixedly. "If you utter any more threats, foreign devil, I will send one of your ears to Yunnan City with your friend. You will have half an hour to decide which one of you departs. Arrange it yourselves."

Bidding two of his men to remain at the door on guard, and to watch the foreign devils closely, he strode out—a compact, businesslike, unhurried man who would obviously carry out his threats to the letter.

Calverly sat down, stretched his arms in their bonds, and laughed. "My word! This is a ruddy go, what? Erskine, did I understand that either I or Plancy takes the message to Garcia?"

Erskine grunted. "Yes."

Seated on the blankets, they stared one at another for a moment.

"But—but this is something formidable!" burst out the Vicomte, in a sudden passionate flood of speech. Words rushed from him; he cursed, reproached himself, poured out a torrent of invective of excited protest. "It is an impossible sum—twenty thousand dollars gold, for each of us!"

"No," said Calverly. "Remember, we have over fifteen thousand between us, Plancy."

"But it will strip us!" cried the Frenchman, aghast. Calverly merely shrugged.

"Fortunes of war, old chap. Erskine here—his mine will put up for him. The British and French consuls will make up what we lack. Which of us goes?"

They argued about it, while the gray dawn lightened into sunrise. The Vicomte resolved to plead with Chang Chin to lessen the ransom demanded, and he called to the guards. One of them came, grinning, and escorted him outside.

"No use, but let him try it," said Calverly. Erskine nodded.

"By all means. How's your side?"

"Eh?" Calverly glanced at him. "Oh, my ribs? Quite all right, thanks. I suppose that rascal will steal the shotgun, eh?"

"Undoubtedly." Erskine blinked and reached out his bound hands for his spectacles. With some effort he got them adjusted. "He hasn't robbed us; that's a blessing."

Calverly laughed. "What do a few dollars matter, when he expects to get forty thousand? Will your company come through?"

"Very likely," said Erskine.

"Lucky beggar!"

Erskine did not respond. He admired the phlegmatic calm of the Englishman, and wondered whether even a pair of broken ribs would have altered it. He spoke up and addressed the remaining soldier, asking the latter to get out his cigarettes for him and light one. The man came over to them and complied, taking a cigarette himself and then pocketing the case with a laughing jest.

"Do you come from this province?" Erskine asked him.

"Yes," said the man. "We are from the governor's army, and this is better than a life of drill! Especially, as you will soon make us all rich."

Now, there are all kinds of dialects, particularly in Yunnan, and in the course of his life here Erskine had gone into the matter quite thoroughly. When Chang Chin had addressed them, he had spotted the bandit leader's dialect as tinctured with Annamese expressions and intonation. This soldier showed the same peculiarity, proof positive that neither of them were Yunnan men.

Erskine relapsed into thoughtful silence, unobservant of the glances Calverly bent upon him from time to time. Presently the Vicomte was brought back, cursing luridly. Chang Chin had refused any compromise, and their time was up. One must depart at once.

"You go, then," said Calverly calmly. "Your consul can wangle the governor into doing nothing. Don't let him start out a few regiments of troops to find us; no use in being found with a slit throat. Eh, Erskine?"

"Correct, of course," said Erskine. "No doubt about it, this bandit will keep his word. We'd better send in letters by you, Plancy. I'll send a code wire to my company in Singapore, and you can get a reply right off."

"Never thought of that!" exclaimed Calverly, with a loud laugh. "Excellent idea! But we can't write with our arms bound—"

Chang Chin entered with several of his men. Broad daylight had broken by this time. The bandit approved the suggestion at once, ordered the three unbound, and they secured writing materials from their still unplundered effects. Calverly dashed off a note, and Erskine carefully wrote out a telegram in code, to be forwarded to Singapore. The Vicomte took these, shook hands, and was escorted out.

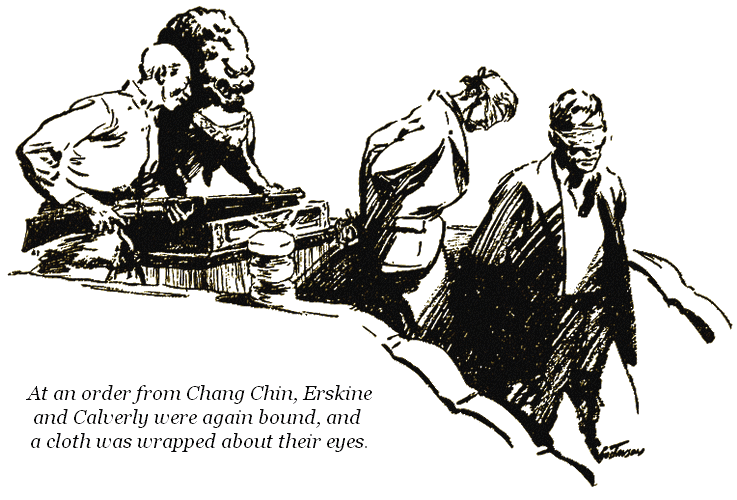

At an order from Chang Chin, Erskine and Calverly were again bound, and a cloth was wrapped about their eyes. Then they were led outside, aided to get into the saddle, and presently went riding away, with the chattering, laughing voices of men around them. Not, as Erskine noted, the voices of Yunnan men.

NOON found the two captives unbound, confined in a grass-

thatched forest hut with their few belongings, two rifle-armed

guards stationed constantly at the door. Chang Chin and the eight

men who composed his bandit following were encamped in the open,

beside the hut. The jungle clearing was walled about by trees and

giant vines. The horses grazed near by; Erskine estimated they

had been a good hour getting here, and Calverly agreed.

"An hour at least, perhaps more. Well, what's the odds, old chap? If Plancy does the business, we'll be free tomorrow."

Erskine merely nodded, having become rather taciturn. It was odd, he reflected, that their chop-boxes and their personal effects had not been looted; their two servants had disappeared entirely. Chang Chin had forbidden them to talk with the guards. Erskine noted that the bandit leader was neglecting no precautions, having stationed sentries out on the trail leading to the clearing.

"It's a well-planned job, what?" said Calverly, mouthing his pipe. "The blighter knew we were coming here—said as much. He's in touch with somebody in Yunnan City, of course; all these outlaws have a spy system."

"I think you're right," said Erskine dryly.

Calverly gave him a sharp look.

"Eh? Yes, of course. Yunnan City will be in uproar tonight, what? Cable stories going out, no end. Consular officials buzzing around, and what-not. If Plancy gets us back safe, there'll be a reception committee and a banquet. Popular heroes, eh?"

"The prospect is distasteful," said Erskine. "I think I'll take a nap, if you don't mind."

He yawned, stretched out on his blankets, removed his spectacles, and was presently sound asleep. Calverly surveyed him sourly, dug a pack of cards from his belongings, and began a solitaire game.

THE hours dragged on. The afternoon was nearly over when

Erskine wakened, sat up and donned his spectacles, and found

Calverly dozing. The two guards at the entrance were alert and

vigilant, he perceived.

Erskine lit a cigarette. Then, sitting humped over, his hand stole in under his left armpit and caressed the slender, flat automatic that was slung there. The touch of it gave him security and confidence. Calverly did not know he had it, and Chang Chin had not discovered it in his hurried search. That the weapon might well prove useful, Erskine knew very well, but he was not talking about now.

"Oh!" said Erskine. "You'll have to give up the concession, eh?"

"Absolutely! Plancy had six or eight hundred pounds in the pool, all he had. Poor chap—he'd saved up for years. You know how these Frenchmen are."

"Yes. How long have you known him?"

"About a month before we came up here. I ran into him down in Annam, where we played a bit of polo, and then he chucked his job, and we went in for a shooting-trip." Calverly grinned over his pipe. "We chucked that when we heard about this Black Dragon mine that was going begging up here. Looked it up, then sold out my share in a rubber plantation, and here we are."

As darkness approached, Calverly and Erskine rummaged in the chop-boxes, produced biscuit and sardines, and made a fairly satisfactory meal. Now, as at noon, one of the guards shambled in with a gourd full of clear cold water, although there was no stream in sight. Erskine tasted it, smiled a little, and made no comment.

"You're taking this affair dashed coolly, old chap," observed Calverly, when their meal was finished, and tobacco-smoke rose gray upon the twilight.

"Why not?" said Erskine with a shrug. "You are too. Will the loss hit you hard?"

"Clean sweep," said the Englishman cheerfully. "Don't mind saying that most of our capital was mine."

Erskine glanced at the empty water gourd, and changed the subject.

"We're not so far from our temple," he said reflectively. "We were taken uphill for a time, then halted, then went downhill; I could tell by the pitch of the saddle. This water we've been drinking is from the Black Dragon spring. Same taste. We were brought back close to our deserted temple."

"Eh? Perhaps you're right!" exclaimed the Englishman. "Look here, what price trying to get away tonight?"

Erskine shook his head decidedly. "I'm no fighting man, Calverly," he said. "And it couldn't be done—these beggars keep an eye on us all the time. I've thought of it; we'd be fools to try it. My company will have the money paid over, and it's much better to lose the money than be cut up."

"Oh, quite so," admitted Calverly with a disappointed air. "I suppose you're right, dash it! What's that you have there?"

One of the guards had brought in a lamp as darkness drew down. Erskine had drawn out an envelope and dumped down three pieces of metal, and was playing with them reflectively.

"Three-piece dollar," he rejoined laconically, and went on fingering the two silver dollar-faces, and the thin, glittering nugget of brass, moving them about on his blankets as though playing some abstruse game with the varying combinations of the three objects. After a time he glanced up.

"You gave Plancy authority to get your joint money?"

"Yes, of course. It's all in the hotel safe, in drafts on Saigon. The Banque Industrielle in Yunnan will cash 'em."

"And my company will order the bank to hand over cash, too. All right, then—Plancy can get the cash without trouble. And he's wise enough to come alone, or with a guide."

Calverly nodded. "Don't worry. The authorities won't interfere. They know it's best to obey orders when dealing with these bandit chappies. They may indemnify us later on, eh?"

Erskine shrugged and went on playing with the fragments of his three-piece dollar, smiling a little to himself as he moved them about. A stir at the door; and he looked up to see Chang Chin striding in. The bandit regarded them and spoke curtly.

"Go to sleep now, foreign devils. A couple of hours past midnight, we leave here to reach the appointed place. I shall take you with me. If the money is paid over, you shall go free and join your friend. If any tricks are tried—"

He gestured significantly, a sweep of his palm across his throat, and strode out again. Calverly looked at Erskine and chuckled.

"Let's hope Plancy doesn't try any tricks, what?"

"He won't," said Erskine, and swept the three-piece dollar back into its envelope. "I think I'll write a short note before we turn in—where's that pencil? Thanks."

He scribbled briefly on a scrap of paper, thrust it into the envelope, and pocketed the latter, with a satisfied air.

THE Vicomte de Plancy, upon reaching Yunnan City, became the

center of a whirlpool reaching out to all financial, diplomatic

and news-gathering circles of the provincial capital. The palace

of the governor leaped into commotion, and consular officials

dashed madly about hither and yon. Through it all, the coolest

heads were those of Plancy and of the grim old governor, who was

quite aware that a false move would mean the death of the

captives.

That the treasury of the state would be called upon to indemnify the foreigners, was immediately made clear; and the governor agreed without hesitation. He went into consultation with the Vicomte and the assembled consuls, and Plancy's very fair proposal was accepted. The banks there would put up the money, as the Gomorrah people in Singapore had agreed by wire to pay their end, and if Plancy returned safe with his two companions, the governor would at once indemnify the expended sums. If unfortunate fatalities resulted, there would be large claims for indemnities, which would have to be paid; otherwise, not. It was a very good bargain for the governor, who thus escaped vexatious foreign claims, and Vicomte de Plancy was the object of many congratulations for having thought of the agreement.

As old Doctor Aintree put it, no one suffered at all except the Yunnan treasury, and everyone benefited; which was as it should be. If the governor permitted bandits to exist in his borders, he ought to pay for the luxury.

No objection was raised in any quarter to obeying the instructions of the astute Chang Chin, and early next morning Vicomte de Plancy departed with a guide and the money. Since he would be back before nightfall, a celebration was arranged by the foreign colony, and showers of hearty best wishes followed him as he rode forth. The guide who went with him was in reality an agent of the governor's, and a very high official, though he did not look it.

An hour before noon, the two of them reached the branch road leaving the highway for the Black Dragon village and mine.

As they turned into the road, a curt voice from the trees bade them halt, and Chang Chin himself rode out, pistol in hand, to meet them.

"Have you brought the money, foreign devil?" he demanded.

"I have it," said the Vicomte promptly. "The whole sum, in cash."

"Good. Come with me and get your friends, who are close by. Your guide can wait here until you return. It will not be long. And pay me the money as we go."

The Vicomte handed over the little sealed package, containing notes of large denominations. Chang Chin broke it open, then turned his horse around, beckoned to the Vicomte, and moved on up the road, inspecting the money the while.

Calverly and Erskine, who had been halted with most of the bandits around them, saw their companion return with Chang Chin. The Vicomte waved his hand to them, but the bandit ordered his men to horse, then turned to the three.

"Go," he said. "I should kill all three of you foreign devils, but I will keep my word. You are free."

He put in spurs and went away at a gallop, his men streaming after him as fast as they could mount and ride.

The three shook hands warmly. Vicomte de Plancy was eager, vivacious, bubbling over with delight. He told of the guide awaiting them, told of the man's real position.

"Undoubtedly he's reporting to the governor," he exclaimed. "You see, my friend? It is good news! We do not lose our money. The governor must repay us—we shall lose nothing at all!"

Calverly, wildly delighted, smote Erskine lustily on the back, and swung up into the saddle, for two horses had been left them. The three set out for the highway, Vicomte de Plancy telling excitedly of what had transpired at Yunnan City.

"So you paid over the money, eh?" said Erskine.

"And you should have seen him counting it!" Plancy broke into a laugh.

"He had never seen billets of such a size, eh? Well, my friends, I am overjoyed! It has been a strain, let me tell you. Most people thought the bandit would take the money and then kill us all. Pouf! I knew the rascal would keep his word."

"Yes?" said Erskine dryly. "I believe you did."

"Eh?" The Vicomte darted him a glance, thumbed the spikes of his waxed mustache, and frowned slightly. "Eh? Your meaning, my friend?"

They had come within sight of the guide, who walked his horse toward them.

Erskine drew rein, and slipped his hand under his coat.

"Plancy!" His voice had a sudden edge of steel. "Hands up—quick!"

The little automatic leaped out, flat and ugly in the sunlight. The Vicomte's jaw fell, and slowly he put up his arms.

"Is this a joke, my friend?" he asked.

"No," said Erskine. "Calverly! Wake up, man, wake up! Search him—look through his coat pockets! Go through that saddle- bag of his!"

"Stop!" cried out the Vicomte, his face contorted by anger. "This is an outrage, this is beyond belief—"

"Shut up!" snapped Erskine. "You fool, I saw through the whole thing! Go on and search him, Calverly. You'll understand quick enough."

Calverly hesitated, then dipped into the Vicomte's coat pocket and produced a slender packet of bank-notes.

Five minutes later, packet after packet had been produced, from pockets of the Vicomte and from his saddle-bag. Pale, furious, helpless, he stood in silence while Calverly and the impassive yellow guide ran over the amounts.

"You'd better slip off and join your Annamese friends," said Erskine, "before our English comrade begins to thrash you—he appears to be considering it. Quick! Any of your own money that's left after paying expenses will be handed over to your consulate—you can claim it at will. And here's a little present for you, a departing gift, as it were—"

He thrust an envelope into the Vicomte's hand, just as Calverly turned from the heap of bank-note packets, with a roar of gathering rage.

The Vicomte de Plancy took one look at the Englishman's face, then made a tremendous leap, gained his saddle again, and thrust in his spurs. He was gone like the wind, with the bellowing curses of Calverly pursuing him. At a safe distance he slowed down sufficiently to tear open the envelope Erskine had given him.

Into his hand fell the fragments of the three-piece dollar, and a sheet of paper bearing the brief scrawl:

"There is another moral, my friend. The two faces may be hollowed out, but after all they remain silver. The brass is nothing but brass. I trust you did not pay Chang Chin too much for his work?"

With a chattering scream of inarticulate rage, the Vicomte flung the note and the metal into the road, and drove in his spurs like a madman.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.