RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

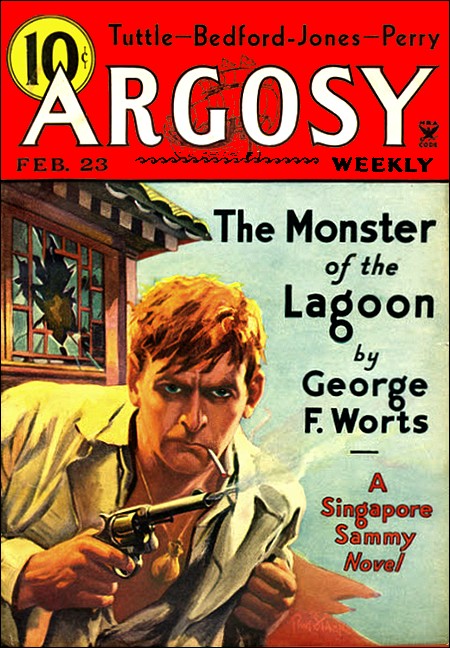

Argosy Weekly, 23 February 1935, with "Spy Against Europe"

WHEN John Barnes stepped aboard the Imperial Airways plane at Croydon field, he was taking his life in his hand, and knew it. When he stepped out of the plane at Le Bourget and got into the bus headed for downtown Paris, Death was chuckling at his ear. His one chance was that nobody suspected what he was doing.

Back in London, just before he left, the American ambassador had made things quite clear.

"It's a new deal all around, Barnes, at home and abroad. We're fighting these Europeans with their own weapons for a change. Remember, you've no earthly connection with Washington! You and the other chaps in the game are taking your chances—long chances, Barnes. You're devoting your time, money, and lives to a cause. You'll have no reward except the satisfaction of serving your country. If you're caught—good-night!"

"Thanks," Barnes said laconically. "Instructions?"

The ambassador handed him an envelope. "Here. Chew up the paper and destroy it before you land at Le Bourget. This assassination of King Boris and the other in Marseilles has turned things upside down; vital information is en route to us, and it must reach Washington at once. There's a leak in the Paris embassy; we can't trust it. If you can get the message here—well, it's up to you."

Aboard the plane, Barnes memorized his instructions. With them he found a list of eight secret agents who had been caught and killed within the past month. None were Americans, but the grim significance of this list was obvious. Barnes knew Europe. He had lived abroad for several years. He had been in business in Paris. Level-eyed, quiet, seldom losing his head, Barnes was no Herculean figure; that was how he got results. Few people suspected his capabilities.

That other men, like himself, were unofficially serving their country, that he had been drawn into a free-lance game against all Europe, was great news. As the bus headed along the cobbled, ugly streets of Paris slipped past. Barnes stared out at them unseeing, his mind active, racing.

A new deal, now! America, unofficially, was taking a hand in the game. The very thought held a tang of adventure. No dirty spy stuff; that was barred. Europe was back in prewar days now. Intrigue, suspicion, assassination, war trembling on every frontier; a secret, merciless war going on beneath the surface. Barnes had caught echoes of it here and there; he knew what he was heading into. A new deal, eh? Yes, European diplomacy was going to get a hot jolt.

His primary instructions were simple. He was to go to the Hôtel Dupont in the Rue du Selz and there await from Sheldon some word, which might come in an hour or a week. Sheldon was trying to get out of Belgrade, which was no easy matter. If he reached Paris alive, he would no doubt be trailed and shadowed.

"Then it's my job to get the information, whatever it is, out of France," Barnes reflected. "But the Dupont! Why pick on that joint, of all places?"

He knew the Hotel Dupont by reputation, which was bad. The little downtown hostelry was no better than a house of assignation. To anyone who knew Paris, the place had an evil stench. However, orders were orders.

Upon reaching the bus terminal at the Crillon, Barnes picked up his one small bag, which was little more than a brief-case, and set out afoot for his destination. He did not know Sheldon; a former newspaper correspondent, who had become the mainspring of America's new initiative against the massed intrigues of Europe. He had a full description of Sheldon, however, and could not mistake his man.

Barnes sauntered along the narrow little Rue du Selz. Gone were the old gay dollar-grabbing days when tourists had flooded Paris. Now the shops looked dingier, the prices were down, only French faces appeared in the streets. Paris was still staggering under depression and the resentment of unpaid national debts.

There was the old Dupont. A mere entry way between two store fronts. Pushing into the place, Barnes found himself in a narrow little hall; a desk on one side, an elevator on the other, a flight of stairs in the rear. At the desk was a man, swarthy, sharp-eyed, who folded up a newspaper and rose.

"Good morning," Barnes greeted him in French. "I'd like a room, a double room. It's just possible that I shall have company later. With bath."

The other beamed. "All things can be arranged, m'sieu. A fine chamber on the third is vacant. Fifty francs."

Barnes protested this price, which was presently cut to forty. He filled out the police registration slip; as instructed in his orders, he gave the name of John Smithson. The police, he knew, would not bother to check up on his identity unless some trouble arose. And if this happened, Barnes intended to be gone before his real name could be involved and his passport impounded.

As he was finishing with the various blanks on the paper, a young woman descended the stairs and came to the desk, leaving her key. Barnes glanced up and thrilled to the sight of her face; dark and lovely, with eyes to hold a man in dreams. Those eyes dwelt upon him for an instant, and he fancied that a startled flame rose in them. Then she was gone out the doorway to the street.

"You are lucky, m'sieu!" and the greasy proprietor winked at Barnes. "M'amselle Nicolas is also on the third—eh, eh, what is this? Tiens, Tiens! Smeethson—name of a little black dog! M'sieu, there was a gentleman here inquiring for one of this name, not twenty minutes ago. He would soon return, he said."

"When he returns, send him straight up to my room, if you please."

The other nodded and opened the elevator door. Barnes was taken up to the third—which, in America, would be the fourth. The ground floor is not counted in France. His room was comfortable enough. It had one window opening on a little iron balcony, and a makeshift bathroom, with all plumbing exposed, the pipes running along the wall.

Left alone, Barnes lit a cigarette and went to the window, which looked out on a court. Probably there were not twenty rooms in this whole "hotel," which was merely a slice from some ancient building, refinished and painted liberally.

"This is a devil of a hole in which to do any waiting," he mused. "But, since it must have been Sheldon who asked for me, I'll not have long to wait. I wonder why that girl gave me such a queer look? Nicolas, eh? Names mean nothing. She was a beauty, all right."

It was past noon; no wonder he felt hungry. A house telephone was on the wall. Barnes gave the proprietor a ring and ordered a meal. Then he began to pace up and down the room. Just what was he in for, anyway? He had not the least idea. Even the ambassador had not known.

Only Sheldon knew just what was up, it seemed. With a shrug, Barnes dismissed his pondering, threw open the window for air, and was tempted to step out on the balcony. He refrained, however. Best not to show himself there.

A waiter arrived with a folding table, spread out an excellent luncheon, and departed with his pay. Barnes drew up a chair, poured some wine, and pitched into his meal. He was nervous and uneasy. He had the distinct feel of something about to happen. His usual calm, his cheerful audacity, was darkened; his high spirits were dulled.

Suddenly came a sharp rap at the door. Before he could respond, the knob was turned.

The door opened and closed again, to admit a man. It was Sheldon; thin, red-haired, with a big nose. A man of forty. He looked at Barnes and grinned.

"Hello! So you got here, eh? I'm Sheldon. Had your description."

Barnes reached for the other's hand, eagerly.

"Barnes is the name—as you seem to know. Join me?"

"You bet. Grub looks good; I'm famished. Got here this morning and have been imagining things ever since. How soon can you clear out for London?"

"In five minutes."

Sheldon dropped into a chair, his back to the open window, and seized on a glass of wine.

"Not quite so fast, but almost, is necessary. You know what's up?"

"I know nothing," Barnes replied. The other was eating as he spoke.

"Hell of a mess. This murder of King Boris has precipitated no end of trouble; we don't know if it means war or what. I had to come via Germany, and couldn't get out. Barely got a plane before the Nazi pincers closed down. I expected they'd have spies waiting to meet me here, but nothing so far. Boy, I've got the goods!"

His blue eyes gleamed exultantly. From his pocket he drew a small but heavy brown envelope, most impressively sealed, which he tossed at Barnes.

"This is a fake, in case you're caught. It's a good fake, too." From his wrist he unbuckled a watch, which he passed over likewise. "Here's the real stuff; get it to the ambassador in London at all costs."

"This watch?" queried Barnes.

"Exactly. Never mind explanations; the less you know, the less you'll give away."

"Right," said Barnes. He gave Sheldon his own watch and buckled on the one given him; it was not running, he observed.

"We've got a hell of a big strike," Sheldon ejaculated between bites. "The lowdown straight out of Belgrade—secret treaties with Italy and so on. The less you know the better, I suppose."

"Who's against us in this deal?"

"Everybody," snapped Sheldon. "We've got what nobody else has, and what they're all after. Me, I'm all shot to pieces. My nerve's gone."

"Any special instructions?" Barnes demanded, pocketing the sealed envelope. Sheldon gave him a shrewd look.

"Yes. This is no kindergarten game we're in. These birds have their countries back of 'em; you and I don't. When you've been in it as long as I have, your nerves will go, too. Suspect everybody! And remember, murder is nothing in this business. They're on to me, all right, but let's hope you've not been spotted. I'll let 'em follow me, while you get across the Channel in a hurry."

"Right. How did you come to pick on this hotel?" queried Barnes.

"I know the chap who runs it; he's part-way straight. There's a hell of a fine girl here—the Nicolas girl. She's been working for Bulgaria, but somebody double-crossed her and I hear she's in Italian pay now. I believe she's in Rome at present."

"She was here when I entered," Barnes said. "The man at the desk called her by name. Very pretty, with dark eyes."

"What the devil! Then somebody lied to me—as usual," Sheldon exclaimed. "No matter. I've not slept for two nights. Lock the door, will you? I was warned they'd try to murder me; I haven't felt safe until now." Barnes went to the door and shot the bolt.

"Wouldn't you be safer in a big hotel like the Lutetia?"

"Nope. They probably know already that I'm here. You'd better be moving. Spare no expense; you may need this, take it." He flung on the table a big wad of various European currencies. "Get out to Le Bourget and hire a special plane; an English one."

"Thanks." Pocketing the money, Barnes began to pack up his few belongings. He went into the bathroom, getting his toilet things. "Who's your danger from?"

"All directions," came the voice of Sheldon. "We're safe enough from the English; they're not interested this time. Boy, with this information we can blow all the others high, wide and handsome! All these double-crossing rats!"

"Hope so." Barnes was packing his toilet articles. "Finish up the grub. I'll get some more at Le Bourget. The room's paid for, by the way."

A grunt from the other room made response.

Swiftly, Barnes repacked. He was in the game at last; elation filled him, all his depression was gone. Now he was alert, eager, tense.

Another half hour and he would be at the air field, then swiftly winging back to England!

"When I reach London, I'll send a wire, so you can take it easy," he called. Sheldon made no response. When he finished his packing, Barnes carried his little bag out into the other room. Then, abruptly, he came to a dead stop.

Sheldon had fallen over sideways in the chair, his head lolling. From the back of his neck protruded the haft of a long, heavy knife.

At this instant came a harsh, determined pounding on the door.

"In the name of the law, m'sieu!" came a stentorian voice. "Open!"

BARNES glanced swiftly about. Sheldon was dead; murdered a moment ago. One glance at that horribly lolling head told the tale. By whom? The room was empty. Ah—the open window, the balcony! Someone had been outside there—

And, in a flash, Barnes knew that this same balcony was his one hope of escape. He knew what threatened him and his precious burden. Let him be caught, accused of this crime, let the French have any handle by which to detain him, and his mission was ruined. It was his job to get through with that information—at all costs!

His hesitation lasted no more than ten seconds. His bag bore nothing to reveal his identity; he dropped it beside the dead Sheldon and darted to the window. There, to his surprise he found that the balcony was not merely confined to his own window, but ran around all the windows of the courtyard. Thus, anyone could go from one room to the others of this same floor. The balcony was now empty, however.

"Made to order for hotel rats, diplomats and assassins!" Barnes thought grimly. A tremendous burst of hammering came from the door of his room. He stepped outside.

To tell whence the assassin had come, was impossible; the rooms to the left, however, would be closer to the stairway. Barnes turned left at a venture. A low cross-bar of iron, over which he stepped, and he was at the adjoining window. Closed and locked. He passed on. At the next, he found the door-like sash also closed. A splintering crash came from behind, a burst of voices; his room had been entered. A moment more, and he would be discovered here.

The window sagged under his hand. He pushed, threw his weight against it; the double sash flew open, and he staggered into the room.

To his vast relief, the chamber proved to be empty.

He closed and fastened the window again, then glanced around. The room was smaller than his own. Women's clothes were in sight. Could it be possible?

Was this the room of the Nicolas girl, which was on his own floor? With a shrug, he dismissed the thought, and stood listening.

The tumult of feet and voices continued. Realization of his own predicament grew upon Barnes with acute force. Smithson would certainly be accused of the murder. Should he walk downstairs now, at once, daring everything? Audacity, always audacity! So thinking, Barnes went to the door and reached for the knob.

At this instant, a key was inserted from the outside.

A laugh, a man's laugh, came clearly to him. The door was unlocked and thrown open, thrown back against Barnes as he slipped aside. It momentarily concealed his figure.

"Very well, I have kept my promise," said a woman's cool, poised voice. "You are in my room. Now clear out—and do it fast!"

"Bah! Don't play the fine lady with me. Shut the door and be sensible," said the man, in a light and bantering tone. "What's all the commotion about?"

"I don't know and don't care," the woman replied. "Get out!"

A laugh, a heavy thudding slap—then the door was slammed shut and locked.

Against it stood the Nicolas girl, flushed, angry. For an instant she did not realize the presence of Barnes, who thus stood revealed. Then her eyes dilated in evident fear. Pallor flashed into her face. She shrank back a little against the door.

"So I was right!" she murmured in English. "When I saw you downstairs, I should have taken warning. I guessed that you must be the man—"

"Apparently you made a very good guess," Barnes said coolly. He was not the person to miss so obvious a cue. Next instant she drew herself up, her dark eyes ablaze.

"You dare not, you dare not touch me!" she exclaimed. "There are police in the building now; at a scream from me, they will come!

"What's more, Sheldon should be here at any moment; Sheldon, do you understand? This is France, my friend, and not Russia."

Barnes was startled. "So it is, Miss Nicolas. What is Sheldon to you?"

"Nothing. He is a friend, and an honest man. No assassin like yourself!"

"Be sensible. I've no intention of harming you," and Barnes smiled faintly. He was badly shaken by what had taken place. Above all, he was conscious of the hatred and fear straining in her eyes.

"Liar! You are trying to trick me, eh?" she said scornfully. "As though I didn't know they were sending you! As though I haven't been watching every day, every hour! Only, I expected it would be Borescu. Come, who are you?"

Barnes produced and lit a cigarette, with assumed composure.

He was fascinated by her beauty—a perilous beauty. After what Sheldon had told him, he knew her for one of those magnificently alluring women who play an old, old game in Europe. What cause they serve, whose pay they take, to whom their reports go, remains obscure; except when one of them is stood against a wall and shot. And not bad women, either. Sheldon had said this was a fine girl, and Barnes could well believe it. Character and brains, not loose morals, are needed to play such a game as hers.

"You just mentioned a Rumanian name with which I am not familiar," Barnes said.

"Borescu? The murderer? Well, never mind evasion. Just who are you?"

"If I told you that," Barnes replied calmly, "you'd know far too much. In plain words, I'm not the person you take me for. I was hiding in this room."

"Nonsense. You even know my name."

"Certainly. Sheldon told me about you. He thought you were in Italy."

"Sheldon!" Her lovely eyes dilated again. "Then he is here?"

"Ten minutes ago, yes. He was murdered, two rooms from here."

Her features tightened; a flame of swift, passionate anger leaped in her eyes.

She believed in him, but she betrayed no shock, no grief. Evidently Sheldon had been nothing to her—nothing more than a friend.

"He was an honest man, that American. And you killed him?"

"No," said Barnes. "Why go into all this business of explaining? It takes too much time, and you'd not believe me anyway."

She regarded him steadily for a moment, and made a sudden gesture.

"I believe you. I may be a fool, but I know when a man tells me the truth. So I made a mistake, and you say he is dead; who are you, what are you doing here?"

"Trying to get out into the street unseen." Barnes smiled in his shy, whimsical manner.

"Ah, I knew he would fail!" she muttered, then collected herself. "Yes, yes, you are right not to trust me. We can trust no one. That is our punishment for thefts, lies, seductions, murders. And it is called patriotism—bah! Well, I knew Sheldon; he was a good friend. Now I must go to London. And you? Where do you go?"

"To London also," Barnes repeated. "I hope to hire a plane."

Her eyes narrowed, then she broke into a quick smile. "I see! Then you are completing Sheldon's errand! Good; we shall go to London together. Aren't you afraid I might try to rob you?"

"Yes."

So lovely, so charming was her smile, that Barnes was astonished once more.

"Oh, I like you! Suspect everyone, eh? Sheldon would have told you that. He told me he expected to meet someone here. Well," and she turned quickly aside, to show a small automatic pistol in her hand, "if I wished to rob you, I could do so. Come along! Let's get out of here before I get knifed in the back! That's Borescu's specialty."

"What's that?" Barnes started slightly. His eyes hardened. "His specialty! It was a knife in the back, thrown from the open window, that killed poor Sheldon! If I thought the murderer—but no. I can't remain here, or delay."

She laid her hand on his arm, looked steadily into his face.

"My friend, I know men; that's my business. I believe you, I like you. What you have just said, proves that Borescu must be here somewhere. Well, I am afraid; I confess it. Certain people have sworn to kill me, and here in this place I'm out of my depth. Give me three minutes, and we'll leave together. Agreed?"

Barnes nodded, and lit a fresh cigarette.

Without more ado, she set to work throwing her things into a bag; the art of light travel was clearly an old story to her. A curtain across one corner of the room provided a closet. She stepped behind this curtain, and he caught a flash of her bare arms above it. She was changing her clothes there.

Barnes looked away. Something at the window caught his eye, a moving object outside and clearly visible through the lace coverings of the sash. A hand and arm, moving across from beside the window, clutching at the knob of the sash and trying to open it.

Then the arm was drawn back. The window had opened a trifle.

Barnes quietly went to the window. Someone was outside on the balcony, waiting and listening. He got behind the slightly opened sash and waited. Miss Nicolas was humming a soft, gay tune.

She had come out from behind the curtain, and was closing her bag.

The hand appeared again. The window-sash was pushed inward. The figure of a man came swiftly into sight; a small man, crouched there, balanced, peering forward into the room. His arm swung up, and a knife was in his hand.

Barnes slammed the sash full against him, all his weight upon it.

There was a crash and tinkle of broken glass, a wild exclamation. The assassin was hurled back against the ancient iron railing of the balcony. It broke under his weight. From the courtyard echoed up a frantic scream, that ceased abruptly.

Barnes found the girl at his side, staring at the broken window, the empty balcony.

"It was he, Borescu!" she breathed. "I saw his face as he fell—"

"Get going," snapped Barnes. "Hear those shouts? It's my one chance to get out, while everyone's around his body. Step on it, girl! I hope the murdering devil is done for!"

He darted to the door. She caught her bag up and joined him; the stairs lay before them, empty. They hurried down together.

A moment later they reached the first floor landing. The stairs were still empty. But below, in the narrow hallway that served as entrance, stood two agents of police. Barnes knew that they were stopping all egress from the hotel. At this instant a burst of frantic voices from the courtyard alarmed the two agents; they swung around, broke into a run, and disappeared. Evidently the body of Borescu was causing a terrific commotion on all sides.

Next moment, Barnes stepped out into the street, holding the girl's bag. She took his arm, very calmly.

"The death of that assassin will make you a hero, my friend."

"Forget it," Barnes broke in curtly. He motioned to a taxicab that swerved in to the curb. "We're well out of a bad mess. Now, I'm going to put you into this cab. You go to Le Bourget, and if I don't show up in half an hour, play your own game."

"What?" Dismay rose in her eyes. "Do we not go together?"

"Not much."

The girl turned to him swiftly. "I don't know your name, but I owe you much," she said earnestly. "Believe me, I shall not forget. I understand; you wish to part with me now, and perhaps you are right. But in London, if you need aid, telephone Charing Cross three eleven and ask for Nicolas. I always pay my debts. Good-bye, my friend!"

And, to the utter astonishment of Barnes, she flung her arms about him and kissed him twice on the lips. Then she caught the bag from his hand and was gone into the cab.

"Le Bourget!" came her voice. "Quickly!"

The chauffeur grinned delightedly at the staring, dumfounded Barnes, and the taxicab went whirring away.

"Whew! What a flame of a girl she is!" thought the American. He signaled another cab. "Going by air, is she? Well, she's welcome. It occurs to me that, with so darned much dirty work going on, this airport is the one place in Paris that's liable to be unhealthy. That's where poor Sheldon slipped up. He came by air, and they knew it, and this knife artist was waiting for him."

He stepped into his cab, ordering the driver to the Hotel Terminus.

With this grim sequence of events at the Hotel Dupont, Barnes had abruptly changed his entire course of campaign. Air was the quickest system of transport, but for this very reason was also the most dangerous. Let the Nicolas girl go by air if she were fool enough to do so! Not he.

Barnes wanted to reach London alive. And dinned into his brain was the determination to accomplish his mission—at all costs.

His taxicab drew up before the dingy old pile of the Hotel Terminus, that once famous but of late rather notorious hostelry beside the Gare St. Lazare. Barnes left the cab, went straight into the hotel, and at the desk he secured a twenty-franc room, for which he paid in advance. He filled out the police registry slip in his proper name, displayed his passport, and was then shown to his room. He explained that his luggage would arrive later.

After five minutes he left his room and descended to the café.

Here he secured a sidewalk table and ordered a sandwich. It was twelve forty. At one ten, as he knew, a train left for Havre, an express that would reach there before dinner time. The question now in the mind of Barnes was whether he had thrown off any possible trailers. Even if not, he still had another string to his bow.

That evening the regular English line left Havre for Southampton, which it reached early in the morning. Altogether the slowest, safest and most comfortable route between Paris and London. Nobody in a hurry would dream of taking it.

At the next table, he observed a jovial fat man who had an expansive gold-toothed smile and a half bald pate. This gentleman settled himself with an aperitif and a copy of L'Écho de Paris, and absorbed himself in the news. Barnes idly read the side of the folded paper that was toward him. But he watched the time as well.

One o'clock precisely. Barnes rose, flung down a note to pay the waiter, and then passed into the hotel by the front entrance.

He passed out at the side entrance immediately after. Heading straight into the station, he bought his Havre ticket, passed the gates, and lingered on the train platform to buy newspapers and magazines from the pushcart there. Preliminary toots of the engine, the calls and whistles of the guards, rang out. The train began to move. Barnes hopped aboard.

There was no crowd. Barnes presently found a first-class compartment that was empty, and ensconced himself in it comfortably. He lit a cigarette, opened a newspaper, and patted the breast pocket in which the brown envelope reposed. Then he suddenly dropped the newspaper and reached into his pocket.

The brown envelope was not there. Gone!

IN the other breast pocket, Barnes found his passport and papers intact, of course. He thought back, swiftly.

True, that brown envelope had been a trifle large for his pocket; but who could have seen it? Who could have taken it? Certainly it had not dropped out. Suddenly he recollected how Miss Nicolas had flung her arms about his neck and kissed him with warm gratitude. At this, his eyes twinkled.

The smart little skirt! She had pulled the job off neatly. At thought of those impulsive kisses, and her quick getaway, his lips twitched amusedly.

"Much good it may do her!" he reflected. "If she did put one over on me, she hasn't gained much by her agility. And to think of her handing me all that line of talk, then calmly picking my pocket! So she's working for Italy, eh? Looks as though Sheldon had told her too much, friend or no friend."

The information that he carried was obviously of interest in more than one quarter. Everybody in the business was out to hijack him, apparently, and there were no rules in the game, as he had been warned. He had just saved the Nicolas girl's life, and she turned around and picked his pocket.

The guard came through, verified the first-class ticket of Barnes, and punched it. Five minutes later, a figure darkened the compartment door, opened it, and entered.

"With your permission, m'sieu? Thank you."

Barnes nodded. Then he took a second look at the man who settled down on the opposite seat—a look of incredulity, of startled recognition. Here was the fat man of the Hotel Terminus café!

The other met his look and smiled, showing the gold teeth.

"We have met before—ah, I remember! M'sieu was at the next table in the café, of course!" the fat man said cordially. "M'sieu is an American, yes? One observes the shoes, naturally. And the first-class travel. Me, I slip in after the guard has gone through, and it costs me nothing. But perhaps m'sieu does not speak French?"

Barnes shrugged. From the very slight accent, he took the man to be a German.

"Afraid I don't understand you, mister," he returned with a nasal drawl. "Don't mind me. I'll take a nap as we ride."

With this he pulled his hat over his eyes, laid back his head, and to all appearance dropped off to sleep. It was no trick to open his lids very slightly—enough to let him look down his nose at the fat, half-bald man opposite.

Barnes was by no means certain whether this might not be a mere coincidence. The fat man sighed, laid aside his hat, and mopped his shining dome. Then he took from his pocket a newspaper, folded in the French fashion, and began to peruse it attentively. The newspaper was the same Écho he had been reading at the café table.

It was folded in exactly the same way, he was reading precisely the same story, now as then.

That settled his doubts. And after a little he observed that the fat man, while pretending to read, was in reality furtively studying him.

Presently a man came past in the corridor. The fat gentleman glanced up, and behind the folded newspaper his hand made a gesture. The man outside nodded and passed on. At this, Barnes concluded that things were threatening to grow uncomfortably warm. He opened his eyes, looked at the fat man, and smiled.

"Just how many of you are there aboard?" he asked in French.

Without the least astonishment, the fat man laid aside his newspaper.

"Ah! You Americans are brusque and to the point, eh?"

His broad features fairly radiated jovial good humor as he spoke. And suddenly Barnes perceived how fearfully dangerous such a man might be. With a nod, the other went on in fluent English:

"I am glad to find you frank; one can do business with such a person." The little eyes bored shrewdly into Barnes. "You are no fool, Mr. Barnes. You are a wise man, I see."

"Eh?" Barnes started. "How the devil do you know my name?"

The fat man burst into a hearty, roly-poly sort of laugh.

"Oh, that is a mere detail! When you arrived this morning from London, we received you, without ostentation, of course. We knew of your coming, my friend. In the little hotel, out of the little hotel again, with that charming young lady! You see, I am quite frank. Now, would it please you to talk business? You are an American, and you know the value of money."

Barnes lifted his brows slightly; this was frankness with a vengeance! So his very coming had been known from the start. "Undoubtedly, money has value," he agreed. This fellow must have the prevalent European notion that all Americans would sell their souls for money. "You, however, have the advantage of me."

"Ah, a thousand apologies! My name, Mr. Barnes, is Rothstern. Let us see, now. Would a hundred thousand francs interest you? I am naming my highest figure. I warn you."

A glitter came into the eye of Barnes. "A hundred thousand francs? It certainly would, if I could get hold of it. That all depends on how it could be earned."

"Very easily. I ask only a few moments to look over the papers Mr. Sheldon confided to you. No one will know; the hundred thousand francs is ready."

The eyes of Barnes widened in very real astonishment for an instant—astonishment that any secret agent could be so obtuse, so blundering. Still, this was evidently the nature of Rothstern himself. Barnes shook his head gloomily.

"Just my cursed luck," he muttered. "No harm in letting you see the papers, if I had them. I discovered it not five minutes ago."

"Discovered what?"

"The envelope's gone," Barnes said, with a dejected air. "All those business memoranda are gone! The girl you mentioned—she kissed me when we parted. No one else could have taken the envelope. A hundred thousand francs lost!"

The little eyes bit into him like gimlets.

"Come, come! You think to fool old Rothstern with such a story? It is true that she kissed you goodby. But to tell me—"

Barnes angrily broke in upon him.

"You don't believe me? Wake up to yourself. Good heavens—a hundred thousand francs just to look over those business agreements Sheldon made? Why, it would be like finding money!" His voice was shrill, impetuous, dismayed. "And now the envelope's gone! If you doubt my word, look for yourself. I've no luggage, search me!" And Barnes began to tumble things out of his pocket. "It was a brown envelope, sealed with red wax. I haven't got it, I tell you; it's gone! She must have taken it."

The fat features became grimly intent and appraising. The vehemence of Barnes was impressive. His agitation, his intense chagrin, his boyish excitement, could scarcely be doubted. Rothstern nodded again.

"So! You tell me such a story and expect me to believe it? Well, it is true that you could not hide the envelope, unless you put it behind your seat-cushions there.

"The brown envelope; yes, that is the one. You will let me see in your pockets, my friend?"

Barnes threw out his hands. "Of course; frisk me if you like. I tell you she got it; and she was going to London by air, too!"

"She is not such a fool," grunted Rothstern. Evidently he had come to the conclusion that Barnes was very much of a fool. "Will you kindly stand up—"

Barnes leaped to his feet. He had been in doubt as to his own course, but now it was plain enough. Rothstern had swallowed the bait of the brown envelope, and so had the girl. What had threatened to become a tragedy aboard the Havre Express, was now turning into comedy or even farce.

So the American made not the least protest as Rothstern swiftly searched him. He seemed quite as anxious as the other man to find the envelope, and even turned out his shoes at the grumbling demand. He carried no papers except his passport and a few personal letters, and it was obviously impossible for him to have concealed that brown envelope anywhere, without the flimsiest search turning it up.

"There are still the seat-cushions," Rothstern said, desisting at last from the search. Barnes, who had put on his shoes again, swore heartily.

"Look all you please. I'm going to the diner for a bottle of beer. But see here! I've told you what became of the envelope and where it is. I should get something for that, at least."

"Swine head!" the other grunted in German, then grinned. "All right, that is true. Here is a hundred francs, my friend."

Barnes took the banknote and walked out.

Not for nothing had he played his cards so carefully. Now Rothstern knew him as a mercenary American more than willing to betray his trust for a few dollars. Others would learn of it. The character so craftily established might, at some future time, prove invaluable to him.

Barnes was still sitting in the diner, lingering over his bottle of beer when the train entered Rouen. Exclamations of astonishment came from the waiters when it became evident that the non-stop express was, for once, halting. They peered out of the windows, and so did Barnes.

For the merest moment, the train halted and then rolled on once more. A smile touched the lips of Barnes as he saw three figures hurriedly crossing the platform to the station—the fat shape of Rothstern, and two other men. Barnes raised his glass.

"To your health, my friend!" he murmured under his breath. "At least the first round goes to the despised American amateur. And the first, let us hope, will be the last so far as you're concerned. You're at liberty to trail the girl, who can take care of herself and give you a headache to boot."

Presently he returned to his compartment, and for the remainder of the journey perused his magazines and newspapers undisturbed. That is to say, from without. As the train was nearing Havre, a very serious disturbance arose in his brain.

He was turning the pages of an illustrated French weekly, when the face of Miss Nicolas suddenly looked out at him. No doubt about it—the same! But it was the line of text below her picture that widened his eyes: "Mlle. Marie Nicolas, fiancée of the Grand Duke Alexis."

Alexis! That rascally old roué of a Russian exile, notorious all over the world for his rascality—about to marry this girl! The thing was preposterous.

"Still, it's none of my business," and Barnes shrugged. "Damned shame, though. That sprig of nobility has been in more scandals and dirty messes than most, which is saying a lot. Well, better forget about it. Maybe it's not true. Even if it is, it's nothing to me."

So he dismissed the matter, a little scornfully, as one does when any charming member of the opposite sex becomes involved in the wrong way.

When the train pulled into Havre, he found himself with time to burn; the boat for Southampton would not leave until nine that night. He strolled about the old streets of the port section, and came at length to the long quays where the English boat and the little ferries for Deauville and Trouville lay berthed by the sheds of the customs inspectors. He stopped in at a nearby café and dined at his ease.

Later he sauntered on to the Southampton boat-shed. Taking nothing for granted now, he stood about smoking and narrowly watching the few people in sight. Freight was being sent aboard, and a number of cars returning from Continental trips. Barnes half expected to catch sight of the huge Rothstern again. Nothing would have astonished him by this time.

However, his critical eye discerned nobody who was in the least way suspicious. He purchased his ticket at last. With some jests upon his lack of any baggage, he passed through the customs shed and went up the gangplank. His passport had been looked over and returned without question, which argued that the Paris police might be looking for Smithson, but were not looking for John Barnes.

A steward led him to the cabin which he had engaged for his exclusive use. It was one of the de luxe cabins on the upper deck. He paused before it, as the steward unlocked the door and switched on the lights. Then he was aware of a voice coming from the adjoining cabin.

"No, no!" It was a low, tense voice, which brought Barnes around like a shot. The window of this next cabin, almost at his elbow, was a trifle open. "No, no! I tell you it is impossible! It would be murder!"

It was the voice of Miss Nicolas.

BARNES quietly tipped his steward and dismissed the man. Then he switched off his cabin lights and stepped outside again. His feet made no sound on the resilient decking. Hereabouts all was deserted; few of these more expensive cabins were used, unless there happened to be a crowd aboard.

Barnes stood poised, waiting, outside that adjoining cabin window. That girl here—why, it was incredible! Or was it? Now he recalled what Rothstern had said about her going by air to London—"she would be no such fool." But how the devil could she have reached Havre, when she had not come on the express? By air, of course; or even by auto. She had let him think she was going to Le Bourget. Perhaps she, too, had figured this slower channel crossing as the safest.

In this, however, she had been far wrong. Barnes listened, then caught his breath. The man's voice that he heard was cold, suave, deadly. An English voice, assuredly.

"Don't try to charm me, you little fool; and they said you were smart! You flew to Deauville to lose yourself in the casino crowds, you caught the ferry over here, slipped aboard—and here I am. And do you know why? Because Rothstern was too cursed clever for you. He telephoned me to look out for you here. Come along; we know you have it. Turn it over or I'll squeeze your pretty little throat still tighter. I'd like to squeeze the life out of you as well! Damn you!"

There was an incoherent, strangling sound, a cough.

"I—I haven't got it!" the girl's voice gasped.

"You lie. We know all about it. You took it from him when you kissed him good-bye."

Barnes turned, and rapped sharply at the door of the cabin. There was an instant of startled silence. Then the man's voice made response.

"Who is it? What do you want?"

"Beg pardon, sir; it's the steward." Barnes made no effort to disguise his voice. He knew the girl was sharp enough to recognize it. "Shall I close your window, sir?"

A suppressed oath. "No! Go away!"

"Very good, sir."

Barnes tried the cabin door. It proved to be locked.

"Confound you, I told you to clear out!"

At this moment a shadow drifted across the deck. It became a man, who closed in upon Barnes and touched his arm, and spoke quietly.

"Here's half a crown for you, steward. You'd best get below decks and leave off bothering passengers who want nothing."

"Oh, thank you very much, sir!"

In the dim radiance reflected from the lights on the quay, Barnes made out a man of about his own height. So there were two of them! He took the proffered coin and turned away. Then he pivoted sharply, abruptly, and his left slammed home in a brutally low body-blow.

There was a gasping groan; the shadowy figure collapsed like a punctured balloon.

Barnes stooped swiftly. He caught hold of the limp figure, dragged it into his own cabin doorway, then inside, and stepped out again. He closed and locked the door. As he did so, the door of the adjoining cabin was flung violently open.

"What's going on out here?" It was the man's voice. "Stacey! Where are you?"

Barnes laughed softly, and stepped into the shaft of light, and down it full into the doorway.

"I'm afraid Stacey has gone on a long journey," he said lightly, whimsically. "At least, the police seem very glad to have hold of him."

He produced a cigarette and lit it, but his eyes missed nothing. This staring man was tall, bony-featured, wide of shoulder. The face was powerful, lean-jawed, ugly. At the back of the cabin, one arm flung out against the upper berth, stood Miss Nicolas. Her hair and dress were disordered; one hand was at her throat, her wide eyes were upon Barnes.

"Who the devil are you?" snapped the Englishman.

Barnes waved his cigarette airily.

"A competitor, my friend, a competitor. Now, Miss Nicolas, hand over the brown envelope, if you please. You know me. My men are below and on the quay. The envelope you took from the American—quickly! Otherwise, you go to jail and this gentleman will follow his friend Stacey. At once, if you please!"

The crisp authority of Barnes' voice, his air of easy assurance, and the disappearance of Stacey, all seemed to cause the dark Englishman inexpressible alarm. He took a step backward, one hand flitting toward his armpit. Barnes merely regarded him with a smile, and the hand dropped. This man was dealing with the unknown; he was beaten.

"My friend," Barnes said pleasantly to him, with a glance at his wrist-watch, "you have exactly five minutes to get off the ship and the quay. As you know, it is a contravention of the French law to carry weapons. Get out, and do it fast. Now, Miss Nicolas, hand over the envelope."

The girl awoke. Her hand went to her bosom; she produced the envelope, now folded and crumpled.

With a subdued oath, the dark Englishman strode past Barnes, and was gone. Barnes swung the door shut. He took a quick step forward and caught the brown envelope from the girl's hand. He glanced at it, then gave her a quizzical look.

"Seals unbroken! Upon my word, you've wasted a lot of time," he said coolly. "And for a young lady so quick with her pistol where I was concerned, you were certainly meek enough when that rascal choked you."

She pointed to the floor. Her pistol lay there. Quick color rushed into her cheeks.

"You don't know him; Truxon is a devil!" she gasped out. "Oh, are you real? It can't be—it's impossible! How did you get here?"

Barnes perceived that she was close to hysterics.

"My dear Marie, you're scarcely the bold bad woman of fiction," he observed, with his warm and twinkling smile. "Upon my word, the more I see of you, the better I like you. Now, tell me why you took the envelope from me, in the first place. Second, why you didn't open it?"

The girl stooped, picked her pistol from the floor, and tossed it into the lower berth. She patted her hair into place, glanced at her torn dress. Barnes began to see that there must have been quite a struggle here before he happened on the scene.

"I owed Sheldon a good turn," she said, and looked him in the face with a hint of frowning wonder in her eyes. "I wanted to help him; and you seemed such a simpleton. You said you were going by air; only a fool would do that, when the air ports are so carefully watched. Why should I open it? I meant to deliver it—"

She broke off abruptly. The quiet smile of Barnes brought a flame of anger into her dark eyes.

"For whom are you working, Marie?"

"None of your business; so you don't believe me? Oh, what a fool you are—no, no." She checked herself abruptly. "No; it's you who made a fool out of me. You're clever; good lord, who'd have thought it of you? Walking in here like this! I owe you everything, yes; but you've made a fool out of me—"

"And you can't forgive it?" Barnes chuckled. "Calm down; keep your head. Nobody's a fool, I'm afraid. It's entirely due to me that Rothstern trapped you here. But who was this Englishman who just walked out?"

"Truxon, of course."

"I honestly hate to corroborate your idea of my simpletonian quality—but who may Truxon be?"

"Still playing innocent, are you?" she said, with an air of scorn.

"If I weren't as innocent as a lamb, I might be in your shoes. You seem to be petrified with terror of everything around you. Borescu puts you in a sweat. This Truxon shows up and you bleat frantically—"

She became white with fury. Barnes paused, listening.

"I take it from the context that Truxon is working with friend Rothstern; yet he's apparently an Englishman. It's too complex for my simple brain. But am I correct in thinking that we're off at last?"

She nodded slightly, as though in relief. Excited voices were sounding faintly from the quay, winches had ceased rattling, and now the ship shuddered to the reverberation of her deep whistle.

"Tell me!" broke out the girl abruptly. "You must know that Truxon and Stacey were broken, smashed, fired out of the English service last year—and lucky they got no worse. But where is Stacey? I know he was watching while Truxon was in here. You had no men, no police—that was all bluff."

"Of course." Barnes started suddenly. "What the devil! I locked Stacey in my cabin. I'd better turn him loose and get rid of him—"

As he strode outside, he was thinking that after all he had learned everything he needed to know—except what he most wanted to know. The girl hesitated, then switched off her cabin lights and followed him.

Barnes found his own cabin door ajar, the room empty. Stacey, obviously, had come to himself and escaped.

"The bird's flown—good!" he exclaimed.

Together in silence, they sauntered to the rail and stood watching the arc-lights of the quays float past and recede, the duller lights of the town blending in a mass and falling away, as the ship pointed out for the Seine estuary. Then Barnes was aware of her quiet voice beside him. She was herself again, composed and poised.

"I can't figure you out. Are you really as new in this work as you appear?"

"You flatter me." Barnes laughed a little. "Question for question. Are you really going to marry the Grand Duke Alexis?"

She gave no evidence of surprise at the question.

"Certainly not. He thought I was, of course; on his part, he was merely after my money. It was all part of the Bulgarian affair, which is quite off the boards by now. But you haven't answered my question."

"My own question ought to answer it. I wish that I knew more about you. Then you are Bulgarian?"

"Heavens, no!" She broke into a short, amused laugh. "I'm an American, silly! Because my father had various electrical concessions over here I began to handle some deals for him, then I gradually worked into the game. It's not a nice game, at times, but I've made a place for myself. I just came from Rome. They made me a very flattering offer there, and it really tempted me."

"Tell me the truth," Barnes urged her quietly. "For whom are you working?"

"You wouldn't know the truth when you heard it," she said bitterly. "At the moment I'm working for no one, and tonight I'm a very humble and defeated person."

Barnes shrugged lightly in the darkness. So she would not come through and be frank! Yet the story that she told had fascinating possibilities; he almost believed it. He found himself liking her strangely, perilously. He liked her very weakness in the face of danger; too efficient a woman loses her most enchanting heritage.

"Yes, I'm new to the business," he said musingly. "So new, that I didn't even take it very seriously, I'm afraid, until—well, poor Sheldon's murder jerked me awake. Well, that's past; it's all over now. We're off for England, and all's well."

"You're optimistic," she said ironically. "You're taking up this business seriously?"

"I hope so."

"For whom, then? Who pays you?"

After information, was she? He laughed to himself. She would not believe the truth.

"Nobody. If some of us put ourselves, our money, our ability, at the service of our country, can anything in the way of money pay us?"

"I know; that's what Sheldon said," she replied in a low voice, to his astonishment. "Oh, I do wish you'd been in it before now! There are so many unsettled things a man like you should have handled, that were frightfully messed up by our diplomatists! Let's hope the new deal extends far and lasts long. Well, I wonder where Rothstern is now?"

"Probably in Paris, gnashing his teeth."

She laughed. "Not he! This business is a gamble; that's why I like it. There are no personalities; if you lose, take it like a sport and try again. But this Truxon is plain bad; so is Stacey. They're hired mercenaries, dishonored men, rascals, working today for the brownshirts, tomorrow for France. So you think we've left all trouble behind, eh?"

Barnes pointed back at the flashing lighthouse.

"There's the answer. Thank you for the 'we.' It's flattering."

"Your optimism is incorrigible. Well, comrade, good-night and pleasant dreams!"

"Same to you. If you need me, call; I'm in the adjoining cabin."

He liked her firm, quick handshake. In fact, he warned himself frankly, he liked her altogether too much.

In his own cabin, he found no traces of his late captive. How Stacey escaped from the locked cabin was a mystery, but it was significant.

"They're a tricky, fly lot, all this crowd of comic-opera assassins," Barnes reflected as he prepared for bed. "Keep one step ahead of 'em and you've got them cinched; that's the recipe. Hand 'em a new deal and they don't know what to make of it. So Marie didn't break into the envelope, eh? Just trying to help out a poor benighted countryman, eh? That's a good line, but I'd hate to trust her very far. Ten to one she's guessed that the brown envelope is a fake. Queer that Sheldon would do so much talking to her; he wasn't the kind to shoot off his mouth without a reason."

So pondering, he fell asleep with the envelope under his pillow.

An insistent hammering at his door finally aroused him to sunlight and the voice of a steward. The boat was docked, everyone was being turned out; and as he had left no call for breakfast, Barnes was just out of luck on this head.

He examined his effects; everything was intact, and there had evidently been no intruders. Dressing hurriedly, Barnes stepped outside and knocked at the adjoining door. No answer. He tried the door and flung it wide open. To his astonishment there was no indication of occupancy; even the berths were made up. Yet the girl had been in this cabin. Seeing the steward pass, Barnes summoned him. To his inquiry, the steward gave him a blank look.

"No, sir, that cabin was not occupied. You had the only one on this deck, sir."

"What? When you brought me up here last night, people were talking in there!"

"Yes, sir, a gentleman did have the cabin engaged, but he went ashore again before we left Havre."

Barnes made his way to the reception sheds. Who had lied to him, and why? He had certainly accompanied her to that cabin after their stroll on deck. Had Truxon engaged it, then? Perhaps; she might have had an entirely different cabin, and had said nothing about it. Yes, she had a shrewd little head and no mistake. Trusted nobody. She was as sharp as a whip—and what a good liar! Besides, he reflected, a fat tip to the steward would have caused that individual to lie fast and hard about the cabin being unoccupied.

The customs and passport formalities were quickly settled. Finding that he had ten minutes to spare before the boat-train departed for London, Barnes dashed into the refreshment counter for a bite to eat.

He was gulping his coffee down when there came a quick, lithe step behind him. He sensed her presence and swung around. Yes, she was there at his elbow, her eyes glinting with dark lights of danger.

"You! Well, I thought you'd skipped out!"

"You would think so," she said in a low voice, not without its touch of scorn. Despite everything, then, she still thought him something of a simpleton.

"I'm in debt to you, and I pay my debts," she went on under her breath. "Truxon went ashore at Havre. He flew across ahead of us. Now there's a small army of the worst rascals in Europe out to get you. Half a dozen of them are planted on the boat-train. They'll stop at nothing, and you'll never reach London alive."

"Whew!" Barnes whistled softly. "Looks as though we needed the good old interference play, eh?"

"Come along with me," she said, not asking him, but as though giving him the order. "I have a car and a chauffeur waiting. Hurry! We can drive up to London before the train gets there, and they'll not suspect. Come on."

She turned and was gone, giving him no chance to argue or question. Barnes followed her swiftly. In a flash he perceived that she had pitched upon the one chance to get through without trouble. He caught up with her at the station entrance.

"What about an appeal to the police?"

The question was rather inane and he knew it. She merely gave him one disdainful look, and went on to where a Daimler was drawn up. A chauffeur in whipcord held open the door. She entered; Barnes followed her in. The door slammed. The chauffeur slipped under the wheel on the right side, and next minute the car thrummed away and shot out like an arrow.

"By all means, this beats the train!" exclaimed Barnes, as they flashed through the streets of Southampton at top speed. To his astonishment, she flung him a look of sheer anger.

"You'd fall for anything, wouldn't you?" she snapped. "And I thought you were smart in spite of appearances!"

Barnes, mystified, blinked at her. Then sudden comprehension rushed upon him. Had she trapped him, after all?

He had no time to think, to speak. Even as he realized what must have happened, how easily he must have walked into her trap, the brakes squealed. The car turned a corner, ground to a halt, and a man from the curb leaped on the running-board. Next instant he was in the car, as it went on again. Barnes looked into a pistol.

"Keep your hands on your knees," snapped the stranger. "Sure he's the right one, Marie?"

"Yes," she said calmly.

BARNES looked at the man, who occupied the jump-seat facing him and the girl. The stranger was dark, grave, intent; he meant business. Barnes turned to Miss Nicolas.

"I congratulate you," he said coolly. "I rather fancied that your confidences of last night were—shall I say, a little too frank to be real?"

"You would," she rejoined cuttingly. The reiteration of this phrase got under the skin of Barnes, brought a flush to his cheeks; her scorn of him bit deeply.

"Was there any truth at all in your recent story about Truxon being here?"

"Yes," she said.

Silence fell. The car rushed on. They were out of the city now, following a surfaced but narrow road at tremendous speed. The chauffeur was expert. He avoided other vehicles in the swiftly-jerking, abrupt English fashion that always brought the heart of Barnes into his mouth; he could never get used to English driving.

"Well," and Barnes turned to the girl again, with the whimsical smile which seemed to anger her, "my eagerness in leaping to your aid would appear to have been wasted, eh?"

"You seem to have a lot to learn," she returned, level-eyed and coolly poised again.

"Undoubtedly. You don't seem overjoyed at the success of your stratagem."

Color came into her cheeks. "I hoped you'd have too much sense to fall for it."

"You really are an excellent liar, you know."

"Call me an actress and be less insulting."

"Insulting? Not a bit of it. I think you're splendid!" Barnes said warmly. She bit her lip, and her dark eyes flamed at him.

"Will you hand over what you carry, Mr. Barnes? Or must we use other measures?"

Barnes shrugged. "I have no choice. You've got me."

With a sigh, he drew the brown envelope from his pocket and handed it to her. She seized it impatiently—and flung it through the open window of the car.

"Simpleton! There's nothing but blank paper in that envelope. No more trickery, if you please! Hand over the real message!"

Barnes broke into a laugh of such genuine amusement that it brought confusion to her features.

"So you didn't waste your time after all, Marie?" he exclaimed. "Blank paper, eh? But that blank paper held secret writing, my dear—"

"It did not," she exclaimed flatly. At this instant, as the Daimler roared along the twisting, narrow lane between the English hedgerows, the chauffeur uttered a sharp cry and slammed on his brakes. They were around a sharp curve, and here the road was blocked. Two cars had halted, the drivers were talking together. The horn of the Daimler blared at them.

"Look out!" cried the girl suddenly. "Look out—"

Her partner, on the jump-seat, flung open the door and leaped out. There was a shot, and he staggered, then fell forward on his face. Several men had appeared from the hedge on either side of the road. They ran at the Daimler, pistols in their hands. The girl made an impulsive movement to rise, but Barnes swept her back with his arm.

"Quiet," he said calmly. "There's Truxon. Keep your head."

Truxon, indeed, coming forward to the side of the Daimler, while another man held the chauffeur covered and helpless. Truxon; lean, dark, savage of face, and there at the roadside was the man Stacey. The girl murmured his name. Barnes looked out at him with interest. A rather weak, vicious sort of face; this fellow Stacey had none of his friend Truxon's vigorous be-damned-to-you hardness.

"Good morning to you," said Truxon, unsmiling, lean, narrow-eyed, looking in at the two of them over his pistol. "Will you step along with me, or must I use force?"

"Just a minute," interposed Barnes. "I'm rather anxious to get up to London. If money will talk—"

"Nothing will talk except what I'm after—and you know what that is," Truxon said, meeting his gaze inflexibly. "Which of you has it, I don't know; you'll both come along. Yes or no?"

Barnes glanced at Miss Nicolas. She was white, her eyes desperate; obviously, this man Truxon inspired her with actual terror. She nodded and rose. Barnes followed her out of the car. Truxon, with a word of direction, piloted them over to one of the two waiting cars and got in with them. He told the man under the wheel to wait, and sat there with his pistol covering Barnes.

The other men flung themselves on the Daimler, beginning a minute search of the car. The partner of Miss Nicolas was lifted and placed inside; whether he were dead or wounded, Barnes could not tell.

A warning cry arose. Another car was coming along the road from Southampton. Truxon flung a command at Stacey, who walked back along the road and met it when it stopped. After a moment Stacey came along to the car in which the three sat, and was holding the brown envelope. He handed it to Truxon, with a grin.

"This was thrown out of their car a few miles back," he said.

"All right. Come along with us. Tell them, if they find nothing, to separate and let the Daimler go. That fellow is only shot in the leg. They can tie him up a bit."

Stacey fulfilled his errand, came back, and got in with them. Truxon flung an order at the driver, and the car moved off.

Barnes took the hand of the girl beside him, and patted it.

"Cheer up, Marie; you made a good try for it—"

"Shut up!" snapped Truxon. "Talk when you're asked, not until, unless you want a crack over the head."

Barnes nodded and kept quiet. He began to understand the paralysis of the girl before this man, whose lean, hard savagery held something inhuman. None the less, after a moment, he ventured to speak again, this time directly to Truxon.

"I'm apparently the person you want. You have me. Is it necessary to bother this young lady?"

Truxon grinned at him. "And let her go with the message, eh? Don't come anything like that. Either one or the other of you has it; and I'll get it. Now shut up."

The car swerved abruptly out of the surfaced road and turned into a lane. This ended at a pleasant old house, green trees about it, a low wall encircling the whole place. The gates stood wide ajar. The car swept in and halted directly before the house door. Truxon got out.

"Come along," he said, waiting, his pistol ready.

Barnes alighted, gave Miss Nicolas his hand, and caught a pressure from her fingers as she followed. Stacey came last. All four went into the house. The driver of the car left it where it was, and went around to the back of the house.

Truxon led his guests into a reception room, where an iron-jawed, elderly woman stood waiting. He nodded to her.

"All right, Wiggins; stand by. You two, sit down."

He tore at the brown envelope and brought to light a wad of blank paper sheets. He glanced at them, and handed them to Stacey.

"As I thought, a ruse. Just to make sure, have them tested at once for any secret writing. Marie, hand over that little pistol you don't know how to use. Quickly!"

The girl fumbled in her hand-bag. Wiggins, the hard-faced woman, came to her and caught the pistol out of her hand. Truxon nodded.

"Take her along, Wiggins, and go over her. Lock her in the east bedroom until I'm ready to talk with her. Report to me as soon as you've searched her. Run along, Marie; no protests, or I'll send Stacey to lend a hand with the search."

Stacey grinned at this. The girl flashed him a glance of contempt, then without a word accompanied Wiggins out of the room. Truxon turned to Barnes.

"All right. Will you hand over the paper we want, or not?"

"Paper?" repeated Barnes, with a puzzled air. "My dear fellow, that envelope was the only thing I have in the way of papers, upon my word! Surely you'll believe me?"

"Absolutely," said Truxon, with his mirthless grin. He handed over his pistol to Stacey. "Your job is to watch him every minute. Don't bungle it. Evidently there was nothing in the car. I doubt if she'll have anything. He's our meat."

Truxon went over to the door, that opened into the hall, and closed it. He came back and looked at Barnes.

"All right. Strip."

Barnes obeyed without any useless protest. Realizing the prominence of the wrist-watch if he were naked, he tossed it on top of his shirt, finished stripping, then retrieved his cigarette case and took out a cigarette. Truxon snatched it from his hand, split it open, found only tobacco, and, with a grunt, handed him a cigarette and a match from his own case. Barnes lit the cigarette with a mild word of thanks.

Truxon slit every cigarette in the case of Barnes, examined the case narrowly, then examined Barnes from hair to toe-nails. He worked rapidly and in silence, but with obvious efficiency, while Stacey lolled in a chair and held the pistol. Upon a couch nearby lay a long dressing-gown of silk, obviously made ready in advance. When he had finished with the person of Barnes, Truxon picked this up and gave it to him.

"Thanks," Barnes said as he got into the silken gown. "I must say that your foresight in all directions is admirable."

Truxon paid no attention, but fell upon the clothes at one side. Every garment was examined minutely. The shoes bore the brunt of this, their heels and soles being slit; satisfied that they held nothing, Truxon bade his prisoner put them on again, and went on with his search. There remained his money, including the roll of notes Sheldon had given him, and the articles from his pockets. These Truxon put on a table, and sat down to his job.

The passport covers were slit and inspected. The pen and pencil were opened up. The larger coins were tested for hollow cavities. The paper money was held to the light and scrutinized under a magnifying glass, note by note.

Barnes waited, smoking, in silence. The wrist-watch, he had already guessed from its being out of order, was merely a hollow bluff enclosing the message. He tried to keep his mind off it, lest Truxon catch the mental wave. His personal letters came next. Truxon glanced over these, then tossed them through the air to Stacey.

"Have these looked over with the blank paper. Under the postage stamps, remember. I don't think we'll find anything there, but neglect nothing."

Truxon picked up the wrist-watch. He looked it over, examined the strap with care, then pried off the back of the case. He pried off a second and inner back. Like many cheap European watches, this consisted of small round works contained in a square case. Over the works, Truxon held the magnifying glass, scrutinized them and then the lids and the whole watch with care.

Then, with a shake of the head, he snapped on the two back lids.

Barnes pressed out his cigarette in an ash tray. Nothing in the watch after all, then. No message. What the devil did it mean?

THERE came a sharp rapping at the door. Truxon rose, betraying no disappointment, and waved his hand at the clothes and other things.

"Take whatever you want, except the clothes," he said to Barnes, carelessly. "You'll not need them for a bit."

Stacey chuckled evilly at these words. Truxon strode to the door and opened it to show Wiggins outside.

"Nothing, sir," she reported. "I've locked her in there, but of course she can break out by the windows and get to the front entrance-roof."

"It'll do for the present," Truxon said. "I'll attend to her after a bit."

Barnes was standing at the table, stuffing the money, passport and other things into his dressing-gown pockets. Suddenly he was conscious that Truxon, from the door, was eying him keenly. Oh, clever Truxon! Just in time, Barnes was aware of the trap. He picked up the wrist-watch, looked at it, tossed it aside, pocketed his cigarette case. Then, as an after-thought, he took up the watch and negligently stuffed it into a pocket with the money.

Truxon came over to him.

"Barnes, I'm going to have that message," he said with calm, impersonal detachment. "It is now on your person. The chief terms of any secret Jugo-Slav entente wouldn't require much space. Well, you can imagine the next stage. I trust you'll not make things unpleasant for us? Here's your chance to hand it over."

Barnes looked at him, wide-eyed.

"The next stage? Oh, come, come! Surely you don't hint at medieval methods?"

"If I must, I'll burn it out of you inch by inch," Truxon said quietly. "Yes or no?"

Barnes merely shrugged.

"Come along," Truxon ordered curtly. "Stacey, follow on. We'll leave him in safety while you go over those papers."

Barnes knew now that he was a lost man; Truxon meant those words to the letter. And, when he had again picked up his possessions, he did exactly what Truxon had meant him to do.

He naturally would make sure of whatever held the hidden message. Somehow, of course, the secret must lie concealed in that wrist-watch.

He followed Truxon out into the hall, with Stacey at his heels. A stairway went to the upper floor of the house. Truxon strode on past this staircase, flung open a door underneath it, and disclosed a corresponding stairs that led down into the cellar. He turned a light switch and started down.

"Come on," he ordered.

Barnes followed him. On the second step, the American caught his toe, stumbled, and to save himself from falling, put out a hand to the wall. From the corner of his eye, he saw Stacey directly behind him and above.

Now, in a split second, Barnes acted. He caught Stacey's pistol-wrist and jerked at the man with all his strength, bending low as he did so. Caught off guard, Stacey was instantly unbalanced. The pistol exploded, drawing a sharp, agonized cry from Truxon below; probably the bullet struck him. Then Barnes had literally pulled Stacey over his head and sent him hurtling down through space, to crash into Truxon's figure.

With one leap, Barnes was back, catching at the door. He swung it shut, found a bolt, and shot it. Then, gathering up the dressing-gown about his knees, he dashed for the open front door and that car that still stood outside.

He was out of the house now, under the entrance portico, jumping for the car. As he reached it, a sudden laugh of exultation broke from him. The ignition key was still in the lock!

There was a crash, a tinkle of bursting glass. Barnes swung open the car door and glanced back. He saw Miss Nicolas scrambling from a window to the portico roof just above, and at the same instant, a pistol exploded somewhere. The bullet whined past his head and pinged off the side of the car.

Barnes leaped in, turned the key, and started the engine. As it roared, another bullet burst the windshield in his very face. The engine roared, and he reached for the gearshift lever. The girl was hanging from the edge of the roof. She came down with a rush, dropped, was up again.

The car moved. Miss Nicolas, panting, came scrambling in beside him, slamming the car door, sinking down breathless. The car pointed out for the open gates. Another bullet came crashing through, and another—

Barnes fell over sideways. He knew that the girl's hand had caught at the steering wheel, her other hand opening up the throttle. He slumped down, falling into darkness.

"Looks like—you win," he muttered, and then went to sleep.

When Barnes opened his eyes and looked up, he blinked in astonishment.

He remembered everything very clearly, up to a certain point. But he could not credit his own eyes. For there, standing beside his bed and smiling down at him, was Marie Nicolas—and with her, the ambassador!

"Welcome back, Barnes," said the ambassador quietly. "Glad to hear you're not badly off after all. I must say you've accomplished something new to London—coming to an embassy in a dressing-gown! You know Miss Nicolas, I think?"

"Too well," said Barnes faintly.

"Well, man—the message?" The ambassador pulled up a chair. "Did you bring it through? Miss Nicolas is one of us. She thought she could handle things better than you could; she was going to bring you safe on from Southampton despite yourself. Where is it? Didn't Sheldon give you a wrist-watch for me?"

"Oh—that!" Barnes gulped hard. "My dressing-gown pocket—"

On a nearby chair lay the silk dressing-gown. The girl snatched it up. From its pockets she tumbled everything out on the bed. With a swift exclamation, the ambassador pounced upon the wrist-watch.

"Thank heaven!"

One of us! One of us! Barnes could only lie there, staring at Miss Nicolas, those words burning into him. One of us!

Drawing out a penknife, the ambassador pried the crystal from the watch. With the blade, he carefully broke off the two hands. He then lifted up the cardboard face inscribed with hours and minutes. This came clear; beneath were several thin slices of paper. He detached these, then sprang to his feet.

"Excuse me, please. I'll have these decoded instantly."

Barnes found himself alone with Miss Nicolas. She sank down on the edge of the bed and met his gaze, a little color rising in her cheeks.

"Oh, don't look at me like that!" she broke out. "I'm supposed to be in Italian pay; yes, I'm really one of you, as he said. I should have told you, perhaps; but I dared not. Sheldon knew; he warned me not to let a soul suspect the truth. I really do some work for Italy, you know. I'm an utter fool. I've made a mess of everything. And you—oh, how you tricked us all! You, with your innocence, your naïve cantrap, your pretended childishness; a Sphinx, that's what you are! A rascal!"

She laughed a little as she looked down at him, a hidden tenderness in her eyes. But Barnes blinked suddenly. His face changed. He came to one elbow.

"What an idea!" he exclaimed. "My dear Marie, you've done something—upon my word! No, no; never mind now. Later on, perhaps. The Sphinx! The Sphinx! Exactly the thing!"

And, forgetting her, forgetting all else, he stared up at the ceiling with a glow of eagerness lighting his face.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.