RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

"The Man from Manchester," Chatto and Windus, London, 1891

He who reads this story will bear in mind that it is a story of human nature—not the human nature of fiction, but of fact. It is a story of the struggle of a man against the inherent weakness of his kind; and those who are loudest in their condemnation should pause lest in their own armour of respectability there be a flaw.

T was a dark November afternoon, and the time within a minute or two of a quarter-past four. The up-platform of the London Road Station, Manchester, presented a busy scene of confusion and bustle, as was usually the case at that hour, for the London express was timed to leave at 4.15. On this particular afternoon there seemed to be an unusual number of passengers, and the train was very crowded. Two gentlemen, however, who were comfortably ensconced in a first-class compartment near the engine, had managed so far to keep out intruders, a judicious tip to the guard having had a magical effect. Excited passengers had repeatedly rushed up to this compartment, but, finding the door locked, had growled out something naughty and gone to another carriage, much to the satisfaction of the two gentlemen, who smiled and seemed well-pleased at the success of their efforts to keep themselves isolated.

These two men were utter strangers to each other, and had come together for the first time in their lives. And it is in the highest degree probable that had a third party, gifted with the power of prophecy, ventured to tell those two men that their chance meeting in a railway carriage on that dark November afternoon was destined to be the beginning of a series of most astounding events that would bring them both into public notoriety, they would surely have laughed the prophet to scorn. In personal appearance the two men presented as striking a contrast as it is possible to conceive. One was a handsome, well-made, burly fellow, not more than thirty years of age. There was something about him—what it is not easy to accurately define—that at once stamped him as representing the better type of the true Manchester Man.' He Lad a round, healthily-coloured face, clean-shaved, save for a somewhat heavy moustache, that was full and round, and curled under to his lips, while his expression was at once frank and pleasing, and gave one the idea that life went well with him, and he enjoyed it. He had dark-blue eyes, that beamed with laughter and contentment. His hair, which was lightish brown, clustered about his forehead in tiny curls, almost like a young boy's. He was well-dressed, and though there was nothing in his dressing that was in the least degree offensive to good or artistic taste, it was obvious that he studied his appearance, and aimed at 'dressing like a gentleman.' His clothes were fashionably cut and fitted him accurately; and a heavy dark-green overcoat, trimmed with Astrakan, imparted to him rather a distingué air, that was further enhanced by his faultless kid gloves, and the crimson silk handkerchief that was allowed just to slightly display itself from the outside breast-pocket of his overcoat.

This gentleman was Mr. Josiah Vecquerary of Manchester. All his people had for many generations been natives of the busy city on the banks of the Irwell, and Mr. Vecquerary prided himself on the fact. And he seemed to take a special delight in making it known to strangers that he hailed from Cottonopolis. I suppose that all men are more or less proud of their birthplaces. But your Manchester man, above all others, seems proud of his. Nor is this pride unjustified, for Manchester in itself is a city to be proud of, and the average middle-class Manchester man is generally an upright, fair-dealing, thoroughly business-like, shrewd, and open-hearted fellow. Blunt of speech and frank-speaking, he strikes you at once as straightforward and reliable. And if you attempt any double-dealings with him you find that you have caught a tartar, for your true Manchester man hates chicanery. He is not suspicious as a rule. By instinct and nature he is very hospitable. He is a staunch friend, but can also be a bitter enemy.

Most of the traits here indicated were prominent in Mr. Vecquerary's character, and he had troops of friends by whom he was highly esteemed.

The Vecquerarys were a very old Manchester family. They had originally come from France, and had then spelt their name Véquérie. But that was at such a remote period that it was no more than a dim tradition amongst the descendants, who had taken kindly to the soil, and become thoroughly imbued with the distinguishing Manchester spirit.

Mr. Josiah Vecquerary was the head of the firm of 'Vecquerary and Sons,' Manchester Warehousemen, whose place of business was in Fountain Street—a thoroughfare long associated with that particular class of business known as the 'Manchester trade.' The firm of Vecquerary and Sons was a very old-established one, and had been handed down from father to son through many generations. Josiah's father had been dead for four years, and Josiah and his younger brother, Alfred, carried on the business. Alfred was single, but Josiah had been married for six years, and was the father of girl and a boy, the latter being five years of age and the girl three.

Mr. Vecquerary's marriage had at first been productive of some little friction and unpleasantness in his family, for he had chosen to marry one of his father's warehouse girls. A well-behaved and pretty enough girl, but as the Vecquerarys were not without pride of race they thought this was a mésalliance, and Josiah's father and mother were particularly annoyed. Mr. Vecquerary, senior, went so far as to refuse to recognise his daughter-in-law; and though when he came to lie on his deathbed he showed some disposition to be reconciled, he died before the reconciliation could be effected. After that, Josiah's mother took to his wife, especially when the first child was born. But most of the other members of the family still manifested a certain disdain for Mrs. Josiah Vecquerary, as they did not consider she was in any way their equal. There is reason to believe that this to some extent influenced Mr. Vecquerary, whose relations with his wife had not been altogether of a cordial character. Not that there had been any serious difference between the young couple, but the husband had occasionally given evidence that he did not consider his wife quite on a level with him. This, however, did not affect him appreciably, and life agreed with him. His business was prosperous, everything went smoothly; he had a perfect digestion, and he loved a good dinner, and knew how to appreciate a choice cigar, and a bottle of old wine.

As we make his acquaintance he is journeying to London on business in connection with his firm. He is in the habit of running up to town once every six weeks on these business matters, and is generally absent four or five days.

The gentleman who so far shares the compartment with him is a very striking contrast. He is a little man, apparently about forty-three. His figure is sparse and shrunken, so that his clothes fit him ill. His face is yellow, with high cheek bones, and he has a very scanty crop of grayish whiskers, and a thin, straggling moustache. His eyes are small and somewhat deep-set, and their expression is not altogether pleasing. He habitually wears spectacles, which tend to make him look a little older than he is. He is slightly bald on the top of his head, and his hair is thin and gray. His general appearance is not altogether calculated to beget the confidence of a stranger, who might in fact experience a sense of shrinking from him, without being able to tell why he did so. The two men have been seated together for several minutes, but with true British reserve neither has yet spoken, The little man at last breaks the ice.

'There seems to be an immense number of passengers to-day.'

He speaks in a high-pitched voice—a thin and trebly voice that is harsh and unpleasant; and he rubs and twists his hands one about the other as if he was oiling them.

'Yes, but it's been market-day in Manchester, and there is generally a rush for this train on market-day.'

Thus spoke Mr. Vecquerary, and his voice was in no less striking contrast to his companion's than his personal appearance was. It was a deep, round, mellow voice, with a pleasant Lancashire burr in it; while on the other hand his companion's had an unmistakable Cockney twang about it.

'Oh, I didn't know it was market-day,' answered the little man, oiling his hands again. 'You Manchester folk are a busy people.'

'Yes, we bear that character,' answered Mr. Vecquerary with a pleasant little laugh. 'But it's evident you don't belong to Manchester.'

'Oh dear no. It is my first visit. I am connected with the law, and I came down here two days ago on a little matter of business, but I confess I am rather glad to get away.'

'Why?'

'Well, it's a dirty, gloomy sort of city, and the people are very boorish.'

'As regards the city,' answered Mr. Vecquerary quickly and decisively, as though resenting the remark, 'you have seen it under every possible disadvantage, but any city would look gloomy in this filthy November weather. The people, however, are all right. They may seem boorish to a stranger, but when you come to know them you'll find out how warm-hearted and hospitable they are.'

'Ah,' exclaimed the little man with a sceptical snigger.

At this moment the guard of the train hurriedly unlocked the door, and said apologetically: 'Gentlemen, I am sorry I cannot reserve the compartment for you, as the train is so full.'

A porter came up carrying a hand-bag, a railway rug, bundle of umbrellas, and various odds and ends, and having deposited these things on the scat and in the rack, he got out and helped two ladies to get in. That done, the door was slammed to; the guard locked it; the shrill blast of the signal whistle resounded through the station; the engine uttered a shriek, and then the train went out into the fog on its way to London.

THE two ladies who had thus become fellow-passengers with Mr. Vecquerary and the lawyer were both of them singularly pretty women. The elder of the two could not have been more than seven or eight and twenty. She was a pronounced blonde, with a complexion like a ripe peach, and a most bewitching mouth, the lips of which, when parted, revealed teeth of the most perfect evenness and whiteness. Her hair, which lay on her forehead in graceful waves, was of that shade which may best be likened to old gold; and it was so abundant that it formed a large knob at the back of her well-shaped head. She had the soft blue and entrancing eves that generally accompany such complexions, and her figure was so shapely that not even a hypocritic could have found fault with it. A neat little boot displayed itself from beneath the snowy frill of her petticoat; and as she removed one glove to take a handkerchief from her satchel and wipe her face, she revealed an exquisitely-shaped hand, white as a lily, with perfectly trimmed and kept nails. Several diamond rings sparkled on her fingers, and she wore a diamond and ruby bracelet on her wrist.

Her companion would not be more than seventeen. She was a brunette, with keen bright eyes, and hair of a very dark shade of brown. There was an arch coquettishness in her expression which was rather an attraction than otherwise. They were both exceedingly well dressed, and conveyed the impression that they were favourites of fortune. They occupied the corner immediately opposite Mr. Vecquerary, and for some minutes that gentleman somewhat rudely stared at these two pretty women, and wondered what relation they bore to each other. They could not be mother and daughter, because the younger one was too old and the elder one too young for them to be so related. Mr. Vecquerary's speculations were soon set at rest, however, by hearing the young girl address her companion as 'Auntie.'

The little man, who had been seated on the same side as the ladies, seemed to be no less interested in them than Mr. Vecquerary was, and in a few minutes he changed to the opposite corner so that he might see them better.

Before reaching Stoekport there is a pretty long tunnel to be traversed, and as the train clashed into this tunnel the breaks were applied with such suddenness that the passengers were all but jerked off their seats. Then the engine whistled shrilly, and the train came to a standstill.

'Oh dear, I hope nothing is wrong,' exclaimed the elderly lady to her companion, in evident trepidation. This was Mr. Vecquerary's opportunity to speak to them, and he availed himself of it. He hastened in the blandest tones to assure them that there was no danger. The train, he said, had stopped because the signals were against it, owing probably to there being another train in the station ahead. In a few moments the train began to move slowly, and in due time passed out of the tunnel all right.

This little incident had been an introduction for Mr. Vecquerary, and he made the best of it, and for a long time he chatted pleasantly with the ladies. He had a very pleasant, genial manner with him, and his conversation was of a kind welt calculated to interest the fair sex. In fact, he proved that he knew what most men nowadays do not know—the art of talking to ladies so as at once to engage their attention and interest them. For a considerable time he had the field to himself; but during that time his unknown male companion sat in his corner in a manner that was somehow suggestive of a tarantula spider, which sits huddled up in its nest, its glittering eyes fully extended on the look-out for prey. At length the unknown—still like a tarantula when it spies prey—darted forward, and opening a neat little hand-bag, he took therefrom a small round basket, in which, cosily nestled in immaculate cotton-wool, were five most tempting-looking peaches. Extending the basket towards the ladies, he said:

'Permit me to offer you, ladies, a peach.'

His high-pitched, squeaky voice was an unpleasant contrast to the full, round tones of the Manchester man, and as he had not hitherto spoken to the ladies, and his movement and manner of making the offer were somewhat abrupt, his act, kindly meant perhaps, did not make the impression it otherwise might have done. The younger lady gave an uneasy glance at her aunt, who returned it; but at last said, with a gracious smile:

'Oh, thank you, you are very kind, but really we cannot deprive you of them.'

'I assure you, madam, you will afford me great pleasure if you will take them,' urged the little man. Pray do.'

Thus pressed, the ladies each took a peach, and the little man, having got his introduction, followed it up and talked incessantly, although Mr. Vecquerary did not allow himself to be driven from the field, and quite held his own against his rival. I say 'rival' advisedly, because the little man, it was unmistakably evident, was anxious to make himself as agreeable and acceptable to the ladies as Mr. Vecquerary had done.

Thus, all the way to London, these four fellow-travellers chatted and laughed freely. The ladies alone were known to each other; the men had met for the first time, and they and the ladies were strangers, and yet these four, engaged in a pleasant little social comedy now, were by-and-by to become actors in a grim and tragic drama.

As the train steamed into Euston, Mr. Vecquerary ventured to inquire of the ladies if they expected any friends on the platform; and the elder lady answered somewhat hesitatingly, and, as it seemed, almost apologetically, saying that they did not expect anyone.

'May I have the pleasure, then, of looking after your luggage and procuring you a cab?'

The offer was accepted with a gracious smile of thanks; and when the train came to a standstill, Mr. Vecquerary sprang out, handing the younger lady out, and the two went off to reclaim the luggage. That done, they returned to where they had left the elder lady. They found her already seated in a cab which the little man had got, and he had made himself useful by handing in the small packages, and was still standing talking to his fellow-passenger when the other two came up. As soon as the young lady had taken her seat beside her aunt, Mr. Vecquerary gracefully raised his highly-polished hat, saying:

'You have made the journey up to London so exceedingly pleasant for me, and I have enjoyed your conversation so much, that I would venture on the liberty of asking to whom I am indebted for so much pleasure?'

The elder lady's face crimsoned a little, and she seemed to hesitate; but it was only for a moment. Then she opened her satchel, took therefrom a pearl and silver card case, and gave him her card. The next moment he was waving his hat in adieu as the cab drove away, and as soon as it was out of sight he moved a little so as to catch the rays of a gas lamp, and he read on the lady's card this name and address—Mrs. Sabena Neilsen, 28, The Quadrant, Regent's Park.

'Dear me, what an exceedingly pretty name!' remarked someone in a squeaking little voice at his elbow.

The someone was his fellow-passenger. Mr. Vecquerary thrust the card into his waistcoat-pocket, and seemed annoyed.

'Yes, it is,' he answered grumpily.

'Are you going to be in town long?' asked the little man.

'No, only for a few days.'

'You stay at an hotel, probably?'

'Yes; the Golden Star, Charing Cross. I always stay there when I come up.'

'Strange,' smiled the little man. 'It's a favourite house of mine, for I live in Craven Street, close by; and I often drop into the Star in the evening for a game of billiards. As we go in the same direction I'll share a cab with you if you like. There's my card.'

Mr. Vecquerary took the card, and found that his companion was 'Mr. Richard Hipcraft, solicitor.' It was a somewhat curious name, and Mr. Vecquerary could not help thinking somehow that the name was suited to the man. However, although he was not very favourably impressed with Mr. Hipcraft, he consented to share a cab with him; having got their luggage, they drove off together.

FOR many hours after Mr. Vecquerary had parted from his lady travelling-companions, his thoughts were occupied with them, or, rather, with one of them; and perhaps it is needless to say that one was Mrs. Sabena Neilsen. Her charming manner, her sweetly pretty face, her engaging conversation, had made a very deep impression upon him, and he could not turn his thoughts from her, although he had a wife and two children in Manchester. But mixed up with his thoughts of the lady was the objectionable Mr. Hipcraft; and irrational, and inconsistent, and ridiculous as it may seem, Mr. Vecquerary actually felt jealous of the little lawyer. Wherefore jealous? it may be asked. Ah, you must know a good deal of the foibles and vanities of human nature to understand that. Mr. Vecquerary was not without a certain self-consciousness of his own superiority when compared with Mr. Hipcraft. That is, he was superior to him physically—in personal appearance, and he believed he was also superior mentally and morally. That, of course, was an assumption of vanity pure and simple; but does not every man think himself superior to someone else whom he may know? Mr. Vecquerary had been anxious to monopolize the attention and conversation of the ladies during the time they were journeying up to London; Mr. Hipcraft had, with a fellow-traveller's privilege, intruded himself on the little party, and Mr. Vecquerary was annoyed and jealous accordingly. That was foolish, and also wrong; but Vecquerary was human.

Now what he should have done was this: after having parted from the lady he should have dismissed her from his mind once and forever. She was apparently a married lady, and he was a married man. Therefore his thinking of her with feelings akin to admiration was not compatible with the due regard he ought to have for his position and his honour. Not that he had any dishonourable intentions at this time; but he was labouring under the spell and fascination of the lady's presence, and he had a strong desire to see her again. Many men would, under the circumstances, have resisted that desire; others would not, and perhaps could not, have done so. And in the latter category Mr. Vecquerary must Le classed. So he made a resolution, and having dined Well, he went to bed after smoking his nocturnal cigar, and slept soundly.

The next day Mr. Vecquerary was engaged in business up to four o'clock. Then being free, he returned to his hotel, washed some of the London grime off him, arrayed himself in a spotless shirt, and a brown velveteen coat—an article of attire he had a great partiality for—and looking very handsome, and very gentlemanly, he jumped into a hansom cab, and ordered the driver to take him to 28, The Quadrant, Regent's Park. Arrived at his destination, he dismissed the cab; and then, with some small feeling that he was not justified in being there, he went up the steps of the house, and rang the bell. The door was speedily opened by a white-capped and white-aproned servant; and he was informed, in answer to his inquiries, that Mrs. Neilsen was at home; and being shown into the handsomely-furnished drawing-room, he requested the attendant Phyllis to take his card to the lady.

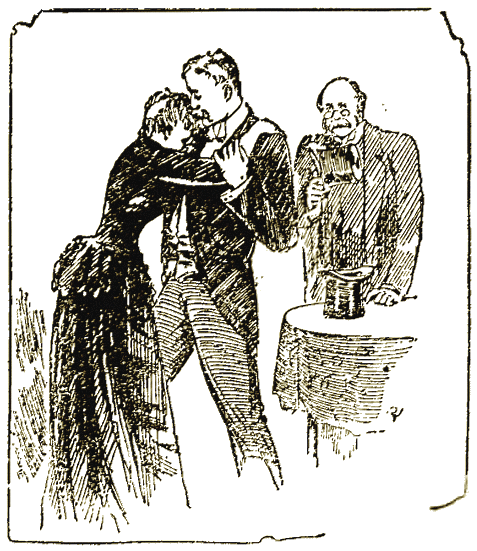

It was fully ten minutes before the lady appeared. If she had looked charming the previous day in the train, she looked doubly so now in an evening dress of delicate blush-rose silk, which admirably suited her complexion. He rose, and stammered forth an apology for his presence there.

'Pray be seated, Mr. Vecquerary; she said, not without some embarrassment, and yet gracefully. 'I did not think when I parted from you and the other gentleman yesterday, that I should see you both again so soon.'

'Both of us!' exclaimed Mr. Vecquerary, opening his blue eyes to their fullest possible extent.

'Yes; Mr. Hipcraft—is not that his name?—called this morning to restore to us a tiny scent-bottle I left in the railway-carriage. He honestly confessed that he purposely kept it in order that he might have an excuse for calling upon me.'

'He is a cunning rascal,' returned Mr. Vecquerary, with something very much like a growl, while his brows were knit with a frown.

'Indeed! Are you personally acquainted with him?'

'Oh no; pardon me!' and Mr. Vecquerary felt very embarrassed.

'And may I venture to inquire if you have any property of mine to restore, for I am very careless when I travel?' asked the lady, with a touch of irony, and yet smiling sweetly.

Mr. Vecquerary felt foolish now, and he was conscious that Hipcraft had scored a point, and from that moment there arose in his breast a positive hatred for the lawyer.

'No, I—I have not,' he stammered; 'but I will be no less candid than this Mr. Hipcraft; he emphasized the name contemptuously. I—I wished to see you again,' the lady's colour deepened, 'and,' Vecquerary went on, trying to excuse his conduct to his conscience, 'I thought I might have the pleasure of making your husband's acquaintance.'

Mrs. Neilsen's face became scarlet, and her manners betrayed that she was greatly troubled and embarrassed. She seemed to become suddenly interested in an album on the table, but it was only an excuse to hide her face from him.

'My husband,' she faltered, 'is—is not here. He is abroad.' Then suddenly, and with the obvious intention of changing the subject, she asked: 'Are you going to remain long in town, Mr. Vecquerary?'

'For a few days only.'

Mr. Vecquerary did not altogether feel comfortable. He was conscious of two things—firstly, that he had no right to be there; secondly, that the beautiful woman before him had some mystery in connection with her life. He could not, on his slight acquaintance, venture to question her, and yet he felt he would give a great deal to know her story. She proved herself a diplomatist, however, for she talked delightfully about the theatres, concerts, music, etc., giving him no chance to do more than to get in a monosyllabic response now and again to what she said. And at last she rang the bell, and told the servant to ask Miss Muriel to come there. 'Muriel is my niece—the young lady you saw yesterday.' This to Mr. Vecquerary.

'She lives with you, then?'

'Yes, she is my constant companion, and is a very charming and dear girl.'

Mr. Vecquerary was about to give expression to some complimentary remark, when the door opened, and Muriel entered the room. She looked a picture of girlish sweetness and grace. She wore a cream-coloured dress trimmed with red, and a dark red rose was in her hair.

'This is my niece, Miss Muriel Woolsey,' said Mrs. Neilsen.

Muriel seemed surprised at Mr. Vecquerary's presence, bit she shook his hand and smiled upon him. Then she sank down in an attitude of perfect grace on an ottoman at her aunt's feet, and rested her white hands on her aunt's knees. The two women were a study of grace and beauty, and Mr. Vecquerary was so carried away by his feelings that he paid them the most extravagant compliments. And then, having remained to the utmost limit of time that etiquette permitted, he reluctantly took his leave, having first asked for and obtained an apparently unwilling consent to call again.

Mr. Vecquerary drove straight back to his hotel, for he had invited two friends to dine with him. Usually a very lively and entertaining companion, he was so absorbed and absent-minded on this occasion as to call forth a mild protest from his companions. He pleaded some worrying business matter as an excuse, and at last livened up under the effects of the champagne. After dinner the three gentlemen adjourned to the billiard-room to smoke and take their coffee and liqueur.

'Ah, good-evening, Mr. Vecquerary,' exclaimed a squeaky little voice, as the three entered. The owner of the voice was Mr. Hipcraft, the lawyer.

'Good-evening,' returned Vecquerary with a scowl, and wishing the other at —— Jerusalem, or somewhere else.

If the lawyer was conscious of the brusqueness—and no doubt he was—he did not allow it to affect him. But with a certain unctuous suavity he engaged Vecquerary in conversation, and as Vecquerary rather prided himself on his good breeding, he did not like to be positively rude to the man, for which line of Conduct he could not have found a shade of legitimate excuse. He was about to take a cigar from his own cigar-case, when the little lawyer quickly whippet out his own case, and said:

'Will you pay me the compliment of accepting one of mine? I can recommend them. They are very choice Havannas, sent direct to me by a relative residing in Havanna.'

Vecquerary could not get out of it, so he accepted the cigar, and then Mr. Hipcraft offered his case to Mr. Vecquerary's friends. And they also availed themselves of the offer. Thus the lawyer established a claim to be considered one of the party. A little later billiards were proposed, and Vecquerary and one of his friends played the lawyer and the other friend. They were an amicable and agreeable quartette for some time, and two or three games having been played, the four adjourned to the smoking-room, where more champagne was indulged in.

It would be useless to deny that each of the four men was more or less excited with what he had drunk during the evening, and in that condition when laughter may suddenly, by some injudicious remark, be turned to curses. Incidentally, during the conversation between Mr. Vecquerary and Hipcraft, their travelling companions of the previous day were referred to, and with a sneer, the lawyer said:

'There is something queer about that Mrs. Neilsen.'

'How do you know?' asked the other sharply.

'I guess it,' said the lawyer coolly. 'I called on her this morning'—this boastfully.

'Yes, I know you did.'

'How the deuce do you know?'

'That's my business. I know it anyway.'

The lawyer sniggered scornfully, as he replied:

'I suppose you have been hanging round there?'

'And what if I have?'

'Oh, nothing. Only it rather tends to confirm my opinion that the lady is not quite what she seems.'

This was an ill-advised remark, although the lawyer did not mean exactly what the words seemed to imply.

'You are an infernal cad to make any such insinuation,' exclaimed Vecquerary hotly.

'Well, if I'm a cad, it's equally certain that you are a blackguard,' answered the lawyer.

The friends interposed to allay the rising quarrel, but without avail. Wine and excitement deprived Mr. Vecquerary of his usual good sense, and he flicked the lawyer's nose with his finger, saying at the same time:

'You are an ass.'

Mr. Vecquerary was a big man, and the lawyer was a little one, but nevertheless he proved that he could resent such an insult as that, and rising to his feet he struck his opponent in the face. Vecquerary was maddened, and before he could be stopped he sprang up, and striking straight from the shoulder he sent his antagonist all in a heap into a corner.

Most of the men in the room cried shame on Vecquerary, who was secured. The lawyer was helped to his feet. His face was white as note-paper, and blood was pouring from a wound on his temple where a ring on Vecquerary's finger had cut him. He was evidently excited, but also it was evident that he had the power of controlling his excitement, for he spoke coolly and with the air of one who was pronouncing a doom. And strangely enough, at that moment Big Ben, with his solemn, deep boom, began to toll the hour of midnight, and somehow the reverberating, sonorous strokes, as they shivered in the night air, seemed to lend force and point to the man's words.

'Vecquerary,' he said, with a sibilant emphasis, 'this blow shall cost you dear, and prove a curse to you as long as you live.' Every word was deliberately uttered, and the man who uttered them might have stood as a model of concentrated hatred and revenge.

R. VECQUERARY was an impulsive and excitable man but, like most such men who are quick to resent an insult but as quick to forgive, he was generous and ready to admit an error. He saw at once that he had been too hasty, no less than too severe, in inflicting chastisement on Mr. Hipcraft, and, being neither frightened nor affected by that gentleman's denunciatory and prophetic outburst, he put forth his hand, saying with frank honesty:

'I am sorry for this. I have done wrong. I apologize, and will make what amends I can.'

As may be readily supposed, the quarrel had caused a great commotion in the room, which was crowded with gentlemen; and it is certain that at first the majority looked upon Vecquerary as a bully, and they were not slow to give expression to their feelings by loud cries of 'Shame,' but Vecquerary's expression of regret and apology caused a revulsion of feeling in his favour generally, though there were still a few who took part with the lawyer. As for Mr. Hipcraft himself, his whole manner and his expression were indicative of concentrated rage and disgust. Some men under certain circumstances seem to show all their character at once and Mr. Hipcraft was one of that sort. If an observer had wanted something to have likened him to, it is almost certain that a snake would have suggested itself. It is not altogether easy to give a clearly logical reason why the lawyer was like a snake, unless it was in an unmistakable malignity that made itself manifest in his whole bearing, and a peculiarly wicked look in his eyes.

As Vecquerary put forth his hand the lawyer drew back, and fairly hissed out these words:

'Take your hand, you brute! I should sully myself if I did. I never allow any man in this world to insult me with impunity, and I repeat, this blow shall cost you dear.'

Vecquerary saw at once that further argument would be but waste of time, and, irritated by his opponent's manner, he retorted:

'All right, do your worst. I defy you.'

This was perhaps an unfortunate remark, but he could not help it, and his friends deemed it wise to get him away. As he reached the passage leading from the billiard-room, a gentleman, who had followed him out, said politely:

'Excuse me, sir, but if you take my advice you will try in some way to appease Hipcraft. I know the man of old, and he is one of the best haters I have ever met. He will ruin you if he can.'

In his then frame of mind Vecquerary somewhat resented this advice, coming from a perfect stranger, as a liberty, and he said snappishly:

'I think you had better mind your own business, sir. What have my affairs got to do with you?'

'Nothing,' answered the gentleman with an ironical emphasis.

'As for Hipcraft; continued Vecquerary with an expression of disgust, he is a toad.'

'So he is—a poisonous one,' added the gentleman who had spoken to him, and who with this utterance went back to the billiard-room.

Vecquerary was certainly not a bully, and it is no less certain he was not a quarrelsome man. He was, as a rule, an even-tempered, rather easy-going fellow, fond of the flesh-pots of Egypt, and not disposed to put too fine a distinction on what constitutes social virtue. Let it not be supposed that he was either a roue or a reprobate. He was fond of his wife and his children, and denied them nothing. But when away from his home he displayed a tendency to forget that he was no longer a bachelor. Being of the world he was worldly in the sense of thinking more of this life than of that which is to come. But then the same thing may be said of nineteen human beings out of every twenty. In so far, therefore, as Mr. Vecquerary could be judged by ordinary standards he was a good husband and father, an equally good citizen, and a highly respectable man; ambitious, too, and with an eye to the mayoralty in the city to which he belonged. As yet, however, he was young, but that would be corrected in time, and he was also good-looking, and of attractive manner—two qualities that are apt to be dangerous to their possessor unless counterbalanced by an absence of vanity and a large amount of self-denial and self-restraint.

His quarrel with Hipcraft troubled him sorely—so much so that for many hours he could not get to sleep. He did not attempt in any way to justify his conduct. He felt, in fact, that he had degraded himself, and gone astray from that line of gentlemanly conduct upon which he prided himself. He had with a generous impulse offered to shake his opponent's hand and confess himself freely in the wrong. But that opponent had scornfully rejected the offer, leaving Vecquerary now no alternative but to stand on his dignity, and urge in his defence strong provocation. But what he really dreaded was publicity. He felt that he would rather give a thousand pounds than that this wretched and disgraceful squabble should become noised abroad. It was the thought of the probability of the affair becoming public property that kept him awake. Had his opponent been a less vindictive man all might have ended well, but Mr. Hip-craft was a totally different man to Mr. Vecquerary. Hipcraft had been for many years what is contemptuously termed an Old Bailey lawyer,' and in this particular branch of his profession he had conspicuously distinguished himself, and any case which he took up he fought with a determination and a bitterness that made him dreaded as a foe.

It is said that no one can dabble in pitch without soiling his hands; and it is no less true that a man cannot habitually be dealing with criminals without, unconsciously it may be; catching up some of the mental characteristics that distinguish them. And so Mr. Hipcraft's mind had moulded itself to his particular calling, and having to deal with cunning, craft, greed, and vindictiveness, he had become imbued in a greater or lesser degree with these qualities.

Mr. Hipcraft had many friends and acquaintance, for like clings to like; and whatever a man may be he is sure to find somebody who believes in him; but in a general way Hipcraft was not esteemed. He was considered to be very sharp, and without those restraining feelings of brotherly charity which redeem our common nature. He had been married. He married a lady much younger than himself, and, unfortunately perhaps, the union was not blessed by children. Mrs. Hipcraft, who was pretty and weak, deceived her husband, and that deception brought forth all the innate vindictiveness of his character. From the moment he discovered his wrong he became her sworn enemy. For years he pursued and persecuted her, until, driven to desperation, the poor thing destroyed herself. So much of the world as knew of the circumstances cried shame on him; but with supreme indifference and scorn he justified his course of conduct by saying 'revenge is sweet,' and that an enemy should never be forgiven. It was a cruel doctrine, but it was a creed with Hipcraft, and he claimed to have a right to form his own opinions.

The foregoing synoptical remarks will enable the reader to understand the kind of man Mr. Hipcraft was, and to see at a glance that Mr. Vecquerary had placed himself in the hands of a very cruel enemy, who would have his pound of flesh to the uttermost grain.

Mr. Hipcraft had certainly been severely punished, using that word in the sense in which bruisers use it. In falling after he had been struck he had strained the muscles of his left arm, and had also extensively bruised his shoulder. The back of his head had likewise come in contact with the wall against which he fell, the result being a large and painful lump. But the most conspicuous, and certainly the most galling, damage was the gash over his eye. With lawyer-like exactitude, the first thing he did when his enemy left the room was to secure the names and addresses of as many of those present as possible. Then he wrote in his pocket-book the particulars and details of the brawl, stating the part he himself had taken with impartial accuracy, and that done, he got two or three gentlemen to sign it. His next step was to wash himself and go home. He lived as a bachelor in Craven Street, off the Strand, an old woman acting as his housekeeper, with a young girl to assist her in the housework, for there was a good deal of work to do, as Mr. Hipcraft did not lead an isolated life, but was fond of a little company.

Letting himself in with a latch-key, he rang his housekeeper up, much to that good woman's surprise and disgust.

'Mrs. Hartley,' he said, 'put on your bonnet and shawl and go to Dr. Turner's house, ring him up, and tell him be must come to me at once.'

'Lor' bless me, sir,' exclaimed the woman, 'have you met with an accident?' as she noticed the wound in his temple.

'Yes,' he answered hotly, and in a tone which she knew too well meant that she was to ask no more questions. So grumbling and shivering she got on her things and went off for Dr. Turner, who lived at the bottom of the street. Mr. Hipcraft being a malade imaginaire, as the French say, and always imagining that he had something the matter with his internal organs, was a pretty good customer to Dr. Turner, so that that gentleman, although very much averse to turning out on such a beastly cold, foggy night, felt that he could not refuse to do so. He therefore muffled himself in a big coat and woollen scarf, and stepped round to the lawyer's house.

'I'm sorry, doctor, to drag you out of your bed at such an unearthly hour,' said Hipcraft apologetically, 'but the matter is urgent. I've been shamefully assaulted in the billiard-room of the Golden Star by a low cad and bully from Manchester, and I'm going to make him pay for it. Please to examine this wound.'

The doctor drew off his gloves, put on his spectacles, and did as he was desired.

'Umph! an ugly gash, the result of a blow with some blunt instrument, I should say.'

'A ring,' suggested the lawyer.

'Yes, a ring,' repeated the doctor, 'no doubt.'

'That is it, he struck me here, and a large signet ring on his finger made the gash. Now feel this lump on the back of my head. He knocked me clean down, and my head came in contact with the wall. My arm, too, seems to be strained. I can't lift it, and it's very painful.'

The doctor scrutinized the arm, and felt it with professional skill.

'Yes, some of the tendons are strained, and it will be painful and stiff for weeks.'

'Now, I want you, doctor, to make accurate note of my injuries and condition, as I shall call you as a witness. I have been brutally assaulted, and as you know I am not the man to submit tamely to that sort of thing.'

'No, you are not,' muttered the doctor, with what might or might not have been a soupçon of sarcasm in his tone. Then he drew forth his note-book, jotted down some memoranda, and having dressed his patient's wound, and given him a prescription for a liniment wherewith to rub the arm, he took his departure; and as Mr. Hipcraft closed the door after him and put up the chain he muttered:

'I think, my friend Vecquerary, this night's work will be rather a bad bit of business for you.'

With this self-comforting reflection, Mr. Richard Hipcraft went to bed.

THE following is an extract from a long letter which was received by a Mrs. Haslam, a widow lady of means, residing in Manchester, and with whom Mrs. Sabena Neilsen and her niece had been staying. The letter was a very womanly letter, with a great many petty details about the journey back to town, and a good deal of gushing sentiment about the 'immense enjoyment' the writer and her niece had derived from their stay in Manchester. The only part, however, that will have any special interest for the reader of this narrative is the following:

'Do you happen, dear Nellie, to know anything of a Mr. Vecquerary, who, I think, belongs to Manchester? Now, pray, dear, don't draw any wrong conclusions from this question. I assure you it is prompted by only the idlest of curiosity. The fact is, Muriel and I had for a fellow-passenger on our journey back to town a Mr. Vecquerary, who was so excessively kind that I became quite interested in him. I was surprised to receive a visit from him the day after we got home. He was full of apologies of course, and said that he had simply called to see if we had reached home safely. What artful creatures men are! Don't you think so, Nell? Muriel is quite struck with Mr. Vecquerary, and I don't wonder at it, for he is very good-looking, and such a perfect gentleman. I could not get rid of him until I had reluctantly consented to his calling again. But when he comes Muriel and I intend to be out. However, I am sufficiently interested in the fellow to want to know who he is. So find out something about him, Nellie, will you, there's a dear old darling?'

Mrs. Haslam was the widow of a naval officer, and though she was

under forty she was somewhat of an invalid, and did not go out very

much. Her friend Mrs. Neilsen's letter interested her greatly; and

she prided herself on not being deceived by the artfully phrased

remarks anent Mr. Vecquerary. I suppose the fact is,' thought Mrs.

Haslam, either Muriel or Sabena is smitten with this man. Well,

they had better be careful what they are doing, for there is no

telling any man nowadays.' It will be seen from this that Mrs.

Haslam was somewhat of a philosopher, with perhaps a dash of the

cynic in her composition. And a few days later, in answering at

length her friend's letter, she wrote thus concerning Mr.

Vecquerary:

'You know, dear, that I lead such a quiet and retired life that I have not much chance of learning anything about people who are not included in my own immediate circle of acquaintances. You will, I am sure, readily see, that with every desire to serve you, you place me in a delicate position, because I could not go about openly making inquiries as to who Mr. Vecquerary is. I might compromise myself, for people are so quick to draw wrong inferences, and suspect wickedness where none is intended. I find, however, on reference to the directory, that there is a firm in Fountain Street here styled "Vecquerary & Sons," but beyond that I have not come across anyone who could give me any information about them. Possibly the Mr. Vecquerary you met will be one of the sons, as I gather from what you say that he is young. I should say anyway that there is no doubt your travelling companion is connected with the firm in question, as I cannot find any other Vecquerary in the directory, and the name is a very uncommon one. Take my advice, however, dear, and before you allow this man to form any intimacy with Muriel—for I presume that it is Muriel he is interested in—find out all about him, for men, you know, are so deceptive, and an unprotected woman cannot be too careful. Of course, these Vecquerarys may be highly respectable, and I have no doubt they are, but still one cannot be too cautious in this world. For my own part I should be delighted to hear of dear Muriel making a good match. But do not let her marry merely for money.'

As Mrs. Sabena Neilsen perused this letter, she smiled

ironically, for she was not quite pleased at her friend presuming

to give her advice, and she was amused, too, at the erroneous

inferences Mrs. Haslam had drawn.

'Muriel,' said Mrs. Neilsen to her niece that afternoon as they sat over the cheerful fire in the drawing-room, each engaged in some needlework, 'what is your opinion of Mr. Vecquerary?'

'Oh, well, he's nice enough in his way, as far as one can judge from such a short acquaintance.'

'He's good-looking, don't you think?'

'Yes, passably so.'

'Do—you—suppose that he's interested in you, Muriel?'

The girl broke into a little laugh of derision as she answered:

'Really, auntie, I should say you were his choice, if he has one. Certainly he bestowed upon me no more than the most passing notice, while he seemed to feast his eyes upon you.'

'Muriel!' this severely and in a tone of reprimand.

'Well, auntie, you know it,' retorted the girl, with the most bewitching pout, and speaking in such a decisive way as to leave no doubt as to what her opinion was.

'Well, it doesn't much matter,' remarked Mrs. Neilsen somewhat sharply, for I don't suppose we shall ever hear anything more of him.'

'Perhaps not,' returned her niece carelessly, as though the subject had no further interest for her.

A little later Mrs. Neilsen was alone in her bedroom. She stood before the glass, peering at the reflected image of her own sweet self. She smoothed back the soft, wavy hair from her temples; and if anyone had whispered in her ear just then, 'You are really an exceedingly pretty woman,' she would have answered, or at any rate thought, 'Yes, I know I am.'

She turned from the contemplation of herself to a chest of drawers that occupied a position on the opposite side of the room. From her pocket she drew forth a bunch of keys, and selecting one, she opened the top drawer; and after rummaging the things over for a few moments, she produced a photograph in a double ease, that closed like a book. This she opened, and revealed the picture of a dark, stern-looking man. This portrait affected her.

The soft, womanly expression of her face changed to one that by comparison was fierce. It was an expression that betokened disgust, contempt, cynicism, disappointment. And yet it was hard to associate cynicism with so charming a woman. But it was evident that, whoever that man was whose portrait she contemplated, she bore him no love. And in a few moments she uttered an exclamation of profound disgust; she shut the photographic ease with a spiteful snap, and pitched it into the drawer. Then she closed the drawer with a bang, and drew the keys out savagely, and with a heart-rending sigh she muttered:

'What an unfortunate wretch I am!'

In thus putting her feelings into words, her self-control appeared to be overcome, and sinking on to the sofa, she covered her face with her handkerchief, and burst into tears. Some bitter memory of the dead past had come back, and harrowed her into weeping. But what did she mean by saying she was an unfortunate wretch? As far as outward signs went, she appeared to be a petted favourite of fortune. Nature had made her beautiful, and she did not seem to suffer from poverty, for her house was well furnished, and, though she and her niece constituted the family, three servants were kept, including a cook. That, at any rate, was prima facie evidence of worldly ease. But may not an apple be fair on its rind and yet rotten at its core? A smiling face sometimes masks an aching heart; and often it happens that what seems the most joyous household has the most gruesome skeleton hidden in its closet.

Before Mrs. Neilsen had recovered herself, Muriel came suddenly into the room, and found her aunt in tears.

'Why, auntie dear, whatever is the matter?' exclaimed the affectionate girl in amazement, as, dropping on her knees, she threw her arms round her aunt's neck, and laid her own soft warm cheek against her aunt's.

'Oh, nothing, darling,' answered Mrs. Neilsen somewhat petulantly, as though she was angry with herself for her weakness. 'I'm foolish, and I think I'm a bit hysterical to-day. I've had a crying fit. There, that's all. But it's over now.' She sat upright, kissed her niece, and added: 'We'll go to the theatre to-night, dearie, if you like. It will cheer me up.'

It was so unusual for Muriel to see her aunt in tears, that, naturally the girl wondered what it meant. But she had the good sense not to irritate with questions; and as she and her aunt were very fond of the theatre, she expressed her delight at the prospect of going.

As Muriel rose to her feet her aunt rose too; and taking her niece's hand, Mrs. Neilsen said with some solemnity:

'Muriel darling, I have a dark secret in my life, and some day I will tell you what it is. The memory of it came back to me this afternoon, and made me weep. It was very foolish, but I could not help it. There now, go and dress yourself, and I will tell cook to let us have our dinner in good time.'

As Muriel sat before the glass combing her beautiful hair, she was very pensive, and she wondered and wondered what the dark secret in her aunt's life was.

Dinner over, the two ladies drove in a hansom—Mrs. Neilsen did not keep her own vehicle—to a theatre where a highly-amusing comedy was being performed; and the way in which the elder lady enjoyed herself—or seemed to do so—was not suggestive of a dark secret that was capable of moving her to hysterical weeping.

The next morning, immediately after breakfast, Muriel unfolded the Standard newspaper. She had got into the habit of reading the day's news to her aunt immediately the breakfast things had been taken away. She ran over many items, and at last in an excited tone she exclaimed:

'Oh, auntie!'

'What is it?' asked Mrs. Neilsen, looking up from some work she was doing.

Whatever do you think?' continued Muriel. Mr. Vecquerary has been had up for an assault.'

Mrs. Neilsen's work dropped from her fingers, her pretty face became pale, and with manifest agitation she gave vent to the one word:

'What!'

Then Muriel in an absorbed way read the following paragraph:

AN ASSAULT CASE.—Yesterday, at Bow Street,

before Mr. Jones, a gentleman who was described as of Manchester,

and whose name is Josiah Vecquerary, of the firm of Vecquerary and

Sons, of that city, was charged with committing an aggravated

assault on Mr. Richard Hipcraft, the well-known solicitor. The

prosecutor, who appeared in the witness-box with his head bandaged,

and his left arm in a sling, stated that he was in the smoking-room

of the Golden Star Hotel in company with Vecquerary, when some

words passed between them about a lady whose acquaintance they had

both made while journeying up from Manchester the previous day.

Vecquerary, who is a big and powerful man, called the prosecutor a

cad, and he retorted by calling Vecquerary a blackguard. This

irritated Vecquerary, who struck the prosecutor a violent blow,

knocking him down, and seriously injuring him. Several witnesses

were called to prove the prosecutor's case, including his family

doctor, who was summoned late on the night of the assault to attend

to Mr. Hipcraft's injuries. The doctor described the condition in

which he found the prosecutor; and stated that besides a deep

incised wound over the temple, that was within an ace of being

dangerous, he was suffering from severe contusions, and sprained

tendons of the left arm.

For the defence it was urged that the prosecutor had really begun

the quarrel by speaking lightly of a lady of whom he really knew

nothing; that on the defendant resenting this, the prosecutor

called him a blackguard, whereupon the defendant tweaked his nose.

The prosecutor retaliated by striking the defendant in the face,

whereupon Vecquerary knocked him down.

In spite of the provocation the defendant had received, Mr. Jones

characterised the assault as one of the most brutal violence, and

he felt in doubt whether he ought not to send the defendant to

prison. In fact, he would not have had the slightest hesitation in

doing that, but for the provocation the defendant had received. But

whatever his social position might be, such blackguards as the

defendant represented would have to be taught that respectable

citizens were not to be assaulted with impunity. The defendant,

therefore, would be fined ten pounds, and would have to pay the

prosecutor's medical expenses. The fine was at once paid, and the

defendant, who seemed to feel his position acutely, left the court

with his friends.

'There, what do you think of that?' asked Muriel, as she ceased reading. 'Whoever could have believed that such a quiet, gentlemanly man as Mr. Vecquerary seemed could have so disgraced himself? I declare, there is no trusting anyone now.'

'Muriel, dear,' said her aunt quietly, as she bent over her work, and betraying by her voice that she was a little agitated—'Muriel, dear, don't you think it possible that Mr. Vecquerary must have received very strong provocation indeed? The report says that the quarrel arose from Hipcraft speaking insultingly of a lady they had met the day previous on their way from Manchester. That must refer to me. I did not like the look of that Hipcraft at all, and I rather think it redounds to Mr. Vecquerary's credit that he was quick to chastise a man who had the audacity to speak insultingly of a lady that he knew nothing at all about. Is that not your opinion?'

This argument placed the matter before Muriel in a somewhat different light to what she had first seen it in, and she answered thoughtfully:

'Yes, aunt, you are right.'

'Poor Mr. Vecquerary, I feel quite sorry for him,' sighed Mrs. Neilsen, in a way that left no doubt that her sorrow was something more than mere words.

A little later some friends called and took Muriel off shopping, and Mrs. Neilsen retired to her room to dress. Presently a servant entered with a card on a salver, and as the lady glanced at the card she saw with surprise that the name on it was Josiah Vecquerary.

HE disgrace of figuring in a police-court, to

say nothing of being called a blackguard' by the presiding

magistrate, crushed Vecquerary with a sense of the most absolute

degradation. The record of his life—so far as such scenes

as that at the Golden Star Hotel, in which he had figured so

prominently, were concerned—had been as a tabula

rasa. The Vecquerarys, in fact, claimed to be considered

eminently respectable, and their claim was generally allowed.

Strictly honourable in their business transactions, and liberal

in all their dealings with their fellow-men, their

reputation—in Manchester, at any rate—was very high.

Josiah, as the chief representative, was proud of the family

traditions, which he endeavoured to sustain with honour and

dignity, and there is no doubt he was very popular with those who

knew him. Now, however, a little forgetfulness, and a miserable

squabble in a hotel, had led to his appearing as a defendant in a

police-court case, and to being described by a metropolitan

magistrate as a blackguard.

Unhappily for Vecquerary, his opponent was one of those outrages on our common nature, a man with whom vindictiveness was a creed, a man who believed that it was noble 'never to forgive.' As Vecquerary left the court covered with shame and humiliation, he passed his enemy in the corridor. The lawyer had evidently posted himself there purposely, and in tones of the utmost scorn he squeaked out:

'How do you feel now, Mister Vecquerary? I wonder what your friends in Manchester will think when they hear of your little escapade. And they will hear of it, Mister Vecquerary. And I further wonder'—here he lowered his squeaky voice a little—'what the lady, who is not quite what she seems, will think. Eh?'

This latter remark so galled Vecquerary that the blood rushed into his face and the fire flashed up in his blue eyes. He turned quickly on the speaker, and seemed about to make some stinging retort, when his arm was seized by a friend, who said:

'Do not notice the wretched little cad. Come away.'

Yah,' hissed the small man, as though he was spitting out venom; 'the "little cad" and your dear friend Vecquerary will perhaps meet again some day.'

Vecquerary showed his good sense by keeping silent, and hailing a hansom, he drove off with his friend.

In trying to find a prototype, as it were, for Mr. Hipcraft amongst the lower orders of creation, it has been suggested that in a certain sense he approximated to a snake. We are in the habit of speaking of some men as being 'cunning as foxes,' 'as bold as lions,' 'as relentless as wolves.' It is, therefore, not straining the privileges of similitude too much to say that a man has some of the characteristics of a snake. That is, when aroused he may be vicious, using this word in the sense of being wicked as applied to animals, and more than vicious, he may be venomous in so far as seeking to do his enemy every harm within his power. This trait was a leading one in Mr. Hipcraft's nature. In so far, then, he was like a snake. And he was possessed of another quality which still further justifies the comparison. It is well known that the male and female cobra de capella, one of the most deadly snakes of India, rarely stray far from each other. If a person kills either of the two the survivor when it misses its mate becomes furious, and it is said never forgets its loss. And so revengeful does it grow that it will attack any living thing that comes in its way not of its own kind. Herein, then, the reptile displays that quality of hatred which was so conspicuous in Mr. Hipcraft. Cunning, too, is associated with the snake, and Mr. Hipcraft was cunning. Said he to a friend as they smoked together on the evening of his day of victory in the police-court:

'My revenge is not satisfied yet. I wanted to have got the brute locked up in a common police cell. I wanted to have put the brand of the gaol-bird on him, but I failed. A fine of ten pounds to a fellow like that is nothing. I'd swear an affidavit that he would have given a clean thousand to have kept this matter out of the court, and I might have bled him, but money would not satisfy me. I am a good hater, as you know.'

'Yes, I know you are,' his friend assented.

'I believe in hate,' the lawyer went on. 'If a man wrongs you, hate him, and never let your hate die until you've ruined him. To love your enemies and do good to them that hate you is a parson's doctrine, but it doesn't work out in real life.'

'No,' mumbled the friend mildly, as though he did not altogether feel as if he could endorse, the sentiment.

'I've ascertained,' continued Hipcraft, 'that this fellow Vecquerary has a wife and two children in Manchester. Now I know nothing of human nature if, in spite of that trifling circumstance, he doesn't go fooling round that Mrs. Neilsen. And I'm utteriv ignorant of womankind if she doesn't draw him on till she has got him fast. He is well off, and she is an adventuress. Do you see the connection?'

'Not quite,' responded the friend, with a simple expression of countenance.

'Good Lord: then you must be obtuse: Don't you see, she being an adventuress, and he having money and being a family man, she'll keep up a constant drain on his purse, and he'll submit to it to avoid scandal. A fellow like that has to assume an appearance of virtue, or he would be ostracised, and his business would go to pot.'

'Ah, just so,' responded the friend sententiously and gazing up at the ceiling.

'Now, I shall watch him like a hawk, and when I find that he has been trapped by the siren spells of his charmer, I'll blow the scandal all over Manchester.'

'But that would be injuring his wife and children,' the friend ventured to remark a little timidly.

'And what the deuce do f care for that?' squeaked Mr. Hipcraft, in his objectionable treble, like an angry rat. "The sins of the father must be visited on the children." The brute has injured me, and in seeking to have my revenge I cannot take his belongings into account; I'll leave that for your philanthropists. I am not a philanthropist. I am a hater of those who injure me, and I hate sentiment also.'

'I tell you what it is, Hipcraft,' said his companion, 'I would far sooner have you as my friend than my enemy.'

'I should think you would,' exclaimed the lawyer, with a dangerous curling of his lips so that his uneven teeth wore revealed; and then with a wicked snarl he added: 'Better to have the devil to deal with than Richard Hipcraft as your enemy. I tell you.'

The friend did not seem quite comfortable, and to steady his nerves he took a deep draught from the glass of whisky and water that stood near him, and thus fortified he said, as he wiped his moustache with his hand:

'Hipcraft, I hope I never shall have you as an enemy. You've got a dangerous sting in you.'

'I hope you never will,' was the rounding off remark—which seemed to suggest an ellipsis which might be filled in with 'God help you if you do.'

From the foregoing fragment of dialogue the reader will get another insight into Mr. Hipcraft's character, and even the most charitably disposed amongst us could not honestly say that this gentleman was anything but a most objectionable person. Perhaps he himself did not think he was any worse than the majority of his fellows, He acted according to his lights, and his lights led him to the conclusion that living in a crafty and wicked world he must meet wickedness and craft with their own weapons.

Mr. Vecquerary, on his part, was without craft. He was in many respects weak, if you like; but he would far sooner have done a generous deed than an unkind one. It may seem singular, but still it was only in accord with the weakness I have alluded to that he should have felt morbidly sensitive about Mrs. Neilsen coming to know of his disgrace. He did not so much mind his wife knowing, but he perfectly shuddered at the idea of the affair coming to the ears of Mrs. Neilsen, although she was a stranger to him, and he could not have been affected by anything she might have thought. To fully explain this peculiarity of Mr. Vecquerary's one would have to resort to a process of very subtle analysis, and bring all the laws of metaphysics to bear. Suffice it, therefore, to say that at the bottom of it was a certain vanity, and that vanity was one of his weaknesses.

When he arose on the following morning after his unpleasant experience of a police-court, and after having passed a very restless night, he, as was only natural, eagerly turned to the daily papers, and as he read the report of the case he went white and scarlet by turns. Bitter, indeed, were his reflections, and painful his feelings, and he could not help thinking:

'Whatever will Mrs. Neilsen think if she should see this? She will certainly come to the conclusion that, instead of the gentleman she took me to be, I am an impostor and a cad.'

If he had been asked to argue the matter out, he would probably have argued thus: 'Those who know me well know that I am neither an impostor nor a cad. But those who, like Mrs. Neilsen, only have a passing acquaintance with me, cannot help an erroneous conclusion.' It will be said, and said justly, that he need not have cared what strangers thought. But the fact remains that he did care—at least, he cared so far as Mrs. Neilsen was concerned. That is where his weakness and little vanity conspicuously displayed themselves.

His appetite was quite gone, and his breakfast went away almost untouched. He ought to have been back in Manchester days before this, but had been detained in London by the wretched police case. At first he thought of returning on this particular day. But he changed his plans; went forth to the telegraph-office, and apprised his people that business would detain him in London till the morrow, and then an hour or so later he jumped into a hansom and drove to the Quadrant, Regent's Park. It was a fatal step to take, and he must have been prompted thereto by his evil genius, while his good genius, for some inscrutable reason, remained dumb, and it may be—wept!

WHEN Mrs. Neilsen read Vecquerary's name on the card that the servant handed to her, a little tremor of excitement thrilled her; and this displayed itself in her voice as she said to the servant, 'All right, Jane; I'll be down directly.' Then, when she was alone, she poured a quantity of eau-de-cologne on her handkerchief, and dabbed her forehead with it, as though she was under the impression that it was a sovereign remedy for disturbed nerves.

It was some minutes before she could proceed to finish her toilet, which she had only half completed when interrupted by the arrival of Mr. Vecquerary's card, and though she had told Jane that she would be 'down directly,' a full half-hour elapsed before she had put the finishing touches to her dressing and felt ready to go downstairs to see her visitor. It was evident that she had bestowed extra care in arraying herself, and she had dressed her pretty hair with scrupulous nicety, until it seemed as if not a single hair was out of place. With a final glance at herself in the wardrobe mirror she left the room, and when she entered the breakfast-room, where Mr. Vecquerary was seated, her heart was certainly beating faster than its normal rate, and there was heightened colour in her face. She was not altogether mistress of herself as she came into the presence of her visitor, who rose to greet her.

'Really, Mr. Vecquerary,' she stammered, 'I must apologize for having kept you so long, but I was engaged when the servant brought me your card.'

Of course, she did not say how she was engaged, and perhaps he did not even trouble to think. He feasted his eyes upon her as he took her soft, white hand, and for some moments felt like one under a spell. His attitude and his expression seemed to betray his thoughts, and they were: 'You are beautiful, and I am fascinated.'

'It is I who should apologize, Mrs. Neilsen, for taking the liberty to intrude myself upon you,' he began with a certain woebegoneness in his tone as he led her to a seat, artfully placing her with her face to the light, while he sat with his back to it, and he thus had her in full view; 'but the fact is, I—I have a sort of special object in coming here.'

'Indeed!' this with a pretty archness, as though she had not the remotest idea of the object that had induced him to call.

'Yes, though I don't know, I am sure, whether you will think my small matters justify this intrusion.'

'Don't say intrusion, Mr. Vecquerary,' she remarked sweetly, and then her face coloured as she felt that she ought not to have said that. It gave him courage, however, and he continued:

'It is very kind of you to say I don't intrude. That consoles me for a good deal. Since I had the pleasure of seeing you last I have had a very bitter experience.'

'I am sorry to hear that.'

There was genuine sympathy in her tone; but she was practising a little deceit, because, although she knew full well why he had come and to what he was referring, she affected to be ignorant of it.

'Yes, and I am sure that you will be surprised to hear that, for the first time in my life, I have figured in a police-court.'

'Really, you don't say so!' Here Mrs. Neilsen dropped her eyes, as though the little hypocrisy she was guilty of prevented her from looking him in the face.

His manner was that of eager earnestness as he braced himself for the recital.

'I am sorry to say, Mrs. Neilsen, that the cause of my disgrace was your own charming self.'

'Oh, Mr. Vecquerary, whatever do you mean?'

'Pray do not misunderstand me. Of course, you are entirely blameless. But you will remember the fellow who travelled up from Manchester with us, and who intruded himself upon you?'

'Yes; let me see, what is his name?'

'Hipcraft.'

'Ah, yes, I remember.'

'Well, in the smoking-room of my hotel, he dared to speak disrespectfully of you, and losing my temper I knocked him down.'

Mrs. Neilsen's face was scarlet and her eyes full of passionate fire as she ejaculated warmly:

'The wretch! What could he possibly say against me?'

'Nothing, I assure you, my dear Mrs. Neilsen; and in common honesty I should remark that what he did say was, perhaps, not very serious, and might have been best treated with contemptuous silence. But—but, I felt so deeply interested in you that, though you were all but a stranger to me, I felt impelled to champion you, and entirely losing my temper, I inflicted on the blackguard an undue amount of chastisement, and so have brought myself into trouble.'

'Oh, I am so sorry, Mr. Vecquerary. But how very good of you to take my part!'

'Are you really sorry?' he asked, leaning a little forward.

'Yes, indeed—indeed I am.' She spoke with genuine earnestness, and it almost seemed as if tears were gathering in her eyes.

Yielding to his weaker nature, and carried away by her manner and her beauty, he put forth his hand and laid it on hers, saying the while—

'To have your sympathy repays me for what I have gone through; and I would thrash the dog again to-morrow if he dared to utter a disparaging word against you in my presence.'

She withdrew her hand from his touch, and there was a warm glow in her cheeks.

'Oh, do let me beseech of you, Mr. Vecquerary, not to run any risk on my account; and for heaven's sake do not let my name be mixed up in any affair of the kind.'

Pray don't agitate yourself, Mrs. Neilsen,' he answered, as he resumed his position, with some suspicion in his mind that he had been guilty of a liberty in touching her hand. I pledge you my honour as a gentleman,' he continued, 'that, so far as I am concerned, your name shall not escape my lips in any way that might tend to give you annoyance. But, tell me, are you cross became I championed you?'

I think you showed the true spirit of a gentleman,' she replied with some fervour, 'but it pains me to know that you have suffered for your chivalry.'

'I care nothing for that,' he exclaimed, growing enthusiastic. I could not have suffered in a better cause. But do you guess now why I have come here?'

She hesitated before answering. Then gave utterance to a tiny white lie:

'I cannot exactly say that I do.'

'I will be candid, then. The affair has got into the papers, unfortunately, and as it appears there, I am made to look very black indeed, while the fellow Hipcraft is painted as a snaring saint. I could not bear the thought that you should receive your impressions from the newspaper report, should, unhappily, it chance to fall under your notice'—she did not tell him that she had already read the report—'I therefore resolved to come and ask you to hear my version of the shameful story. I hope I shall not seem guilty of anything like egotism if I venture to remark that I am generally considered to be a gentleman, and I humbly try to justify my reputation.'

A reputation that, I am convinced, is fully deserved,' she remarked with earnestness.

'Thank you. I am truly desirous of earning your good opinion.'

'And, believe me, Vecquerary, you have it.

'I cannot tell you,' he said, and seemingly struggling with his feelings, 'how it cheers me up to be assured from your own pretty lips that I stand well with you.' Mr. Vecquerary was perfectly conscious that in saying this he was saying that which he ought not to say, and he saw, too, for his eyes were fixed upon her in admiration, that his words brought the blushes to her face. But in the presence of this charming woman he did forget himself, and felt as if he could sacrifice all and everything for her sake.

Mrs. Neilsen seemed to understand the embarrassing position which her words and his own had placed them both in, and she hastened to try and undo what had been done.

You see, Mr. Vecquerary, after all, we judge people in this world by their acts and deeds. And so I must judge you. You were exceedingly courteous and kind to me and my niece when as two unprotected women we travelled up from Manchester, and now, as I gather from what you tell me, you have been brought into an unpleasant position because an unmanly wretch spoke lightly of me. Therefore, although we shall probably never see each other again, I shall always remember you with gratitude and respect.'

He looked at her with some astonishment, for these words—'although we shall probably never see each other again'—stung him. He interpreted them as a delicate hint that she did not want to see him again, and his spirits drooped once more. With an impulse that he could not resist, he rose to his feet, and naturally she did the same. His handsome face was clouded with a sorrowful expression that was quite foreign to it, and standing before her and looking at her, although she did not meet his gaze, he spoke thus:

'Perhaps, as you say, Mrs. Neilsen, we shall never meet again. But this I can say honestly, I shall never forget you while I have power to think.'

She cast her eyes upwards at these words and met his, which had a pleading look in them. Her face was no longer red but pale, and it was evident from her heaving breast that she was agitated.

'You really flatter me, Mr. Vecquerary. What have I done to have made such an impression? I did not think that a poor little insignificant woman like myself had the power to attract the notice of anyone, much less a man like you.'

'You do yourself an injustice,' he said quickly. 'Nay, you are quite well aware that you are not a poor little insignificant woman.' He spoke with real sympathy, and almost involuntarily he put out his hand and took hers. For a moment or two she allowed it to remain in his. Then she withdrew it. It was manifest that he wanted to say something else. There was an awkward pause. He leaned towards her, and she played nervously with her chatelaine. Then in a lowered tone, a tone that was meant to be tender, he added—

'Before I go, Mrs. Neilsen, I must repeat that you have made a deep impression upon me. You are so charming that I—'

She glanced at him, as it seemed to him, in anger, and once more the colour leapt to her cheeks.

'Do you forget, sir,' she said, that when you first called upon me you expressed a hope that you might make my husband's acquaintance, and I told you he was abroad?'

Again she turned from him, and her emotion was unmistakable. Had he failed to notice the rebuke in her words, he would have been obtuse indeed. But he was only too conscious that she had rebuked him.

'Pray forgive me,' he said. 'I apologize for having forgotten myself. But, Mrs. Neilsen, I am a man of the world, and I flatter myself I can read signs—some sins, at any rate; and, unless I am singularly mistaken, you have some hidden sorrow. There is some unhappiness between you and your husband; and although I am almost an utter stranger to you, I would crave as an honourable man to be allowed to offer you my sympathy, to ask that I may try to prove myself worthy of your confidence, and to claim the privilege of tendering you the sympathy of an honest man for an honest woman.'

Mr. Vecquerary spoke with genuine sincerity, and at this moment with every regard for honour and truth. His nature was essentially sympathetic, and believing she had a sorrow, he was desirous of befriending her if she needed a friend. But just then he failed to see that he was treading on dangerous ground, and that her beauty had inflamed him. His words, winged with tender sympathy, as they were, found their way to her heart; and though she struggled hard to control herself, the struggle was ineffectual, and she gave way to tears.

'Now I have made you cry,' he cried, reproaching himself.

She laid her hand on his arm as an act signifying gratitude, and in tones of thankfulness she said, in a voice so sweet and low, albeit sad:

'I am very foolish to let you see my weakness. But my life has had some very dark shadows in it. You touch me, indeed, when you so nobly offer to befriend me: but you must not forget that the world does not tolerate a man in your position befriending a woman in mine.'

'What do you mean, Mrs. Neilsen?' he asked eagerly.

'My meaning is surely clear. You are a man, and should understand me.'

He turned from her with a sigh.

'Yes,' he said, 'I do understand you. Society erects barriers, and engraves thereon "Thus far and no farther." It is well that it should be so. And yet society cannot kill the natural sentiment of men and women's hearts. For me to seek to know your story from mere curiosity would be unpardonable impertinence; for me to seek to know it out of the excess of the real sympathy you have aroused within me will at least beget me your tolerance. We have met, and your image will abide with me. We part—I won't say forever, because I shall cherish a hope that Fate will be kind to me, and some day bring us together again. And so, not adieu, but au revoir.'

With a supreme effort she managed to say calmly:

'I do so thank you, Mr. Vecquerary, for your kindness. Au revoir.'