RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

"Six Golden Angels"

Dodd, Mead & Co., New York, 1937

"Six Golden Angels"

The Chicago Herald Examiner, 17 Apr 1938

Six Golden Angels—Six Beautful Women

THE sallowness of Martin, the valet, existed not only in the stained whites of his eyes but even in his yellow fingers, which were spare in flesh and grew larger toward the flat tips. The strength which his clothes concealed appeared in his naked hand, particularly as he gripped the big, streamlined automatic.

With a sort of flat-handed pass he made the heavy gun disappear in his clothes, produced it again through his back, apparently—and all the while watched carefully the face of Gains, the butler, who attempted to preserve a wooden indifference; but his eyes were alive in spite of himself and glinted with every flash of the weapon.

"When you're juggling," said Gains, "you ought to keep to things that don't have a mind of their own."

"I won't let this rod speak out of turn," answered Martin.

"Why you packing it, anyway?" asked Gains, breaking down into open curiosity at last.

Martin allowed the automatic to remain in hiding beneath his coat.

"The old girl ought to have an airing now and then; that's all," said Martin. "And tonight may be the night for her to appear in company."

The buzzer sounded on the pantry wall and the register indicated the library.

"J.J.'s gunna ask me is everything okay," said Gains, rising. "Funny how he gets nervous every time he throws a party, eh?"

"He spent too many years prospecting the Canadian back-country," said Martin. "New York will always be a pretty tight fit for him."

Gains found John James Leggett pacing on the library rug.

"Does everything come along in good shape?" asked Leggett.

"Everything is in order, sir," said Gains.

"Send me Cesare," commanded Leggett.

While he waited for the chef he walked up and down the room looking at the books. Their titles meant nothing to him but the bindings made a pleasant tapestry of color along his walls and gave the room a sort of mental furniture. In this moment of great stress, he was not thinking consciously of his problem but was dimly remembering the hours he had spent in the leather room of the Zaehnsdorf bindery in London, thumbing hard-grained Morocco, or the soft Levant, or sleek vellums, or the deep neck wrinkles of brown sealskin. He had said to Zaehnsdorf's manager: "I want a hundred and ten yards of books. Here's the plan of the room. I don't know a thing about books but I'd like some color on the walls."

That was when the penthouse was rising on top of the huge loft building. Mike Ravenna said it looked too much like part of an English abbey, hoisted halfway to heaven, but that was before the landscape gardener had clothed the penthouse with time. The booming drone of a steamship's whistle on the North River stopped Leggett in front of the mullioned window that filled the whole end of the room. A tremendous steamer was standing swiftly down the tide, making even the huge sky-scrapers seem like a city of toys. It angered Leggett a trifle whenever those monsters passed by, throwing his world out of scale; otherwise he liked the huge vibration of the whistles. He shut the passing of the great ship from his mind and looked down to his roof garden. Now that May put an end to the danger of frost, the gardeners made the whole formal design bloom with color inside the potted box-hedges. In the fountain the three bronze mermaids looked up with laughter at the spray which old Triton blew from his horn; descending, the water rained dazzling gold upon them, for the sun was turning red in the west.

The chef came in and held his tall hat at attention against his breast. The little starved man always seemed to be shrinking from a blow.

"Cesare, why don't you eat some of the stuff you cook?" asked Leggett. "Why do I have to have a skeleton behind every feast?... Now listen to me, Cesare."

"Yes, signore."

"Everything must be perfect tonight. I want you to put your best touch in every dish; make music; make 'em sing. You hear?"

"Signore, everything shall be done con amore e passione."

Leggett went down to the dining room and eyed the massed flowers with pleasure. Afterward he went up to the Venetian bedroom where the girls would leave their wraps. It was not to his taste. There was not a single chair to which a big man could trust his weight; but the women always exclaimed about the damask curtains, the carved and gilded furniture, and the grotesquerie of the little dancing figures which made a frescoed cornice around the walls.

He liked better the bathroom with its sunken tub of pale green marble and the dressing-room with the stiff yellow skirts of the table repeated endlessly in the surrounding mirrors. His own image multiplied in the same manner and it was this sight of himself that drove him away suddenly. Remembering the old prospecting days, lean and hard, it was difficult to identify himself with the swollen body on the long legs, like a crane at a stand in good fishing waters. Like the bird, all the lines of his face dropped down to a long nose and a long, fleshy chin. It was a red face, moist and shining.

Gains called him away to the telephone. A man's voice clear and strong with youth said over the wire: "Mr. Leggett?... Hello, Uncle John! This is David."

"That's not David Ryder," said Leggett. "You're away off at sea on a steamer, David."

"There was a handy little dirigible going across and I shifted to another fellow's ticket," said David Ryder. "Can I see you? I'll be at the hotel...."

"You'll be here!" shouted Leggett. Something stopped his voice. He controlled himself. Then he added: "Come right out. Having a dinner tonight. Rush along so you'll have time to change."

He sent for Martin and said: "My nephew is arriving. I don't know when he'll leave. He takes the guest suite."

"Yes, sir. The suite?" repeated Martin.

"I said the suite. And until he gets a valet for himself, you'll more or less forget me to take charge of him. Though he may not have many clothes to take care of. Not to begin with," added Leggett.

"More or less forget you; yes, sir," said the valet.

Leggett grinned at him.

"You're a cruel, hard, cold sort of a devil, aren't you, Martin?" he asked.

"As you please, sir," said Martin, with none of the French sour going out of his face.

"When you take care of David Ryder, you damned thief,"'said Leggett, "you'll walk on eggs and break none of 'em!"

"Certainly, sir," said Martin.

"Wait a minute," commanded Leggett. "I want to say something."

"Yes, sir," said Martin.

"What am I going to talk to you about now?"

"Something very intimate, sir."

"Why should I be intimate with you?"

"Because you could send me up the river for twenty years by lifting your finger, sir."

"You know, Martin, sometimes I think I ought to have nobody about me except ex-convicts."

"Besides me, you have Gains, sir," said Martin.

"What! Gains, too?"

"Yes, sir."

"Well, I'll be damned," said Leggett.

"Yes, sir," said Martin.

"You hired Gains for me yourself," said Leggett.

"I wanted to share my good fortune... with a friend, sir."

"You think you can trust Gains, eh?"

A very faint smile twisted the mouth of Martin.

"As long as I live, sir; yes."

Leggett regarded him for a moment with a sinister pleasure.

"Why do I enjoy you so much, Martin?" he asked.

"Because you like to own your people body and soul, sir," said Martin.

"That's good. That's damned good because it's true," said Leggett. "The point at hand, Martin, is that the arrival of my nephew unbalances my dinner table tonight. I have to have a sixth woman.... Is there anything in the world that I haven't talked to you about?"

Martin lifted his green eyes to the ceiling.

"No, sir. Nothing," he said.

Leggett laughed a little but kept watching the face of Martin with cautious attention to overlook no shades of meaning.

"How do I seem to you just now?" he asked.

"I think you find this is a very special day, sir."

"I expect it to be a special night," said Leggett. "You think that this fellow Daley really knows something?"

"I am sure of it, sir."

"About one of my guests of tonight?"

"Yes, sir."

"I wonder which one it could be?" murmured Leggett. "Tell me the exact words that Daley used."

"He said: 'I'm bringing the dope in pictures and writing. What I bring is going to blow that party all to hell. After Mr. Leggett's had a chance to look over my stuff and check it, he can pay what he thinks it's worth.'"

"We'll find out what he has when the time comes. Let's get back to the last topic. Every one of the five women who are coming tonight has sold her soul to the devil; do you know that?"

"Certainly, sir," said Martin.

"You're a complacent sort of a scoundrel," said Leggett. "Do you even know their names?"

"The Countess Lalo, Miss Leslie Carton, Mrs. Eric Claussen..."

"How do you know all this?"

"You sent each of the ladies flowers, sir, and the florist confused the addresses and telephoned to straighten them out."

"I think I'll check that with the florist," said Leggett. "Shall I?"

"I hope not, sir," said Martin.

"Then you're a confounded eavesdropper, are you?"

"Yes, sir," said Martin.

"Let it go for the moment. Pay attention to this: My nephew has been educated for twelve years by my money and now that he's through with the Sorbonne he ought to be in line for a good opening in international law."

"Certainly, sir."

"But he's not going to do international law. He deserves something better. For twelve years I've given him just enough money to keep body and soul together. I haven't even smiled on him. I haven't seen him five times in the twelve years. Results? Why, he's managed like a Spartan. He's had enough for tuition and bread and water, so to speak, but he's taken nothing but top marks and honors everywhere.... Now he's going to have his reward.... He's going to have his reward!"

"Exactly, sir."

"I know he's the true steel," said Leggett, "but I want to find out if a dash of wine and a pretty face will upset him. These sheltered students—you never can tell what the world will do to 'em, Martin."

"Certainly not, sir."

"So I want to ask you, of all the young women who have been guests here recently, which is the best? Understand? I want to sit her down at the table with those other five females and see if David Ryder has brains and instinct enough to pick her out of the lot. If he can do that I'll know better how far I can trust him in the world. Because there are going to be five temptations here tonight, Martin, that would snatch Saint Anthony out of his lion's skin. Now the point is—what girl do I know?"

Martin lifted his green eyes again to the ceiling.

"Well, say something. Make a choice," said Leggett.

"I am trying sir," said Martin.

"You impudent rat!" exclaimed Leggett. Then he added: "Wait a minute!... That young girl who's studying singing. That... what's her name?"

"Miss Eileen Durante is the young lady you mean, sir."

"Well, tell me: isn't she the pure quill? Even New York soot can't settle on her."

Martin studied the emptiness of space before he shifted his glance to Leggett and answered, solemnly: "I think you are right, sir."

Leggett smiled at his valet's doubt. I'll get her if I can," he said. "And here's the extraordinary oddity of it: If she'll come, there'll be six girls with golden hair at my table!"

He went to the telephone and got Michael Ravenna.

"Ah! It is John!" said the Italian. "You interrupt me at my collar button, John. I am too fat. I shall have to get a valet like the rich Mr. Leggett to squeeze me into my clothes."

"Mike, you know that girl who's studying singing. Eileen Durante. Can you get her to come here tonight? Not to sing. As a guest."

"Ah, but John! I know the other women who are coming. And Eileen is a little different."

"Damn the difference. I mean, the difference is what I want. Will you get her for me?"

"But she lives like a poor little nun in this city, John. Perhaps she won't want to come. She is nothing but work and starvation; and that poor, gentle, sweet. small voice that never will fill a concert hall!"

"Tell her that I want to help her," said Leggett. "Tell her that I want to see her again because I'm thinking of helping her. As a matter of fact, tonight she may pick up the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow."

"I'll get her," said Ravenna, "but what rainbow? What pot?"

"You'll see one day, perhaps.... Goodby."

For just then a servant came in to murmur: "Mr. David Ryder, sir."

He had shoulders capable of swinging an oar in a college crew and yet he was light enough to ride a middleweight hunter. He wore his gray flannels like an Englishman whose breeding is high enough to permit him to be careless. He had a large head and a face so thin in flesh that one could study the bones and the brain beneath it.

"Hurry now," said Leggett, shaking hands. "You've got barely time to change. Dinner jacket in those bags?"

"Yes, or a white tie if you prefer," answered Ryder, glancing at the tails which Leggett was wearing.

"Snatch the tails and press it," said Leggett to Martin, when they reached the rooms and the bags were opened.

"All this space just for me?" said David Ryder, looking about him at the suite.

"Well, you have to sit, and you have to study, and bathe, and dress and sleep, and it's better to have a special room for each," answered Leggett. "Like this layout?"

"I like it," said Ryder. "It looks rather Louis Quinze, but cleaner."

"Yeah, you've used your eyes," said Leggett. "Hate to see a young fool shut out the world with a book. By the way, how could you afford to come over on the airship?"

Ryder was stripping. He paused to reach into an open bag and pull out a pair of dice. He rattled them on the table. "Just a bit of luck," he said. Leggett picked up the dice and looked at them as though he never had seen the spots before. He did not lift his head from the study.

"Luck, did you say?" he asked. "Handmade luck?"

The rustling of clothes stopped and the silence lasted long enough to make Leggett look up.

"Luck, I said," remarked Ryder.

He pulled off the rest of his clothes. The muscles of a very strong man garnished the flat of his stomach and clasped his shoulders with long fingers.

"How much do you owe?" asked Leggett.

"I thought this was in the way of being a party and a homecoming and all that," answered Ryder, scorning the idea with his own smile.

He went into the bathroom; the shower began to roar. Leggett followed him.

Ryder stepped out of the shower and began to towel himself.

"Where did you get that scar over the eye?" asked Leggett.

"Some of those French fellows are pretty tough," answered Ryder.

"Street fight?" asked Leggett.

"No. Five-ounce gloves. Sports promoter used to put me on now and then. I wasn't a headliner but I made quite a bit betting on myself."

He was rubbing himself powerfully, the pink coming out through the thick of the tan. Leggett lighted a cigarette.

"Ah, well," he said, "I was thinking you might be all Ryder, meek and mild. I forget about the Leggett blood in you.... Come here, Martin!"

Martin came in with his eyes on the floor.

"Look at him," said Leggett, "and tell me if he's a good fellow."

"I can see that he is your nephew, sir," said Martin.

"I'll be damned if that's not a recommendation," growled Leggett. "Listen to me, Martin. I changed my will today when Chisholm came to see me. I have about thirty millions. I left the whole kaboodle to a good, pure-minded, quiet, gentle student named David Ryder. Aside from some little bits for devoted servants like Martin, of course. Was I a fool when I did that?"

David Ryder, his heel on the edge of the bathtub, lifted his head and looked at Martin with gray-green eyes, as he dried his toes. And Martin looked back at him.

"Mr. Ryder and I hope that you will live for many years, sir," he said.

"Don't switch to him all at once, Martin," said Leggett. "I may change my mind."

They went into the dressing room and Ryder slid into the clothes that Martin held for him. Gains rapped on the door to announce that Mr. Ravenna and Mr. Porter Brant and Miss Sydney Galloway and the Countess Lalo had arrived.

"Let's go down and meet these people," said Leggett. "Old friends of mine. Almost too friendly, considering how young a lot of 'em are."

As they went down the stairs a guitar started thrumming and a strong bass voice, sometimes husky, sometimes a little oily and bubbling, began an Italian song.

"That's Mike Ravenna," said Leggett.

They went on into the library.

Mike Ravenna, as the center of the picture with half a dozen extremely pretty women around him, leaned back in a deep chair with his legs thrust out before him, his coat off, and the guitar resting on the huge, rolling shelf of his stomach. Three other men, overshadowed by his singing, were hardly noticeable on the margin of the group.

The song ended as Leggett came in. He said: "I want everybody to know my nephew, David Ryder. David, the fat man is Ravenna. He knows all the meat in New York's political stew. Here's Jimmy Hickey, the famous columnist and scandal-breeder. Now, Jimmy, take hold of David and tell him all the dirt about everybody in the room. When he knows what he's meeting, you can introduce him."

Wrinkled and gray before his time, with a thin, ratty face, Jimmy Hickey took Ryder by the arm and led him aside. A tall, handsome girl came up to them and shook hands with Ryder. She said: "If you put your snake's tongue on my reputation, Jimmy, I'll smack you down. Mr. Ryder, I'm Eric Claussen's wife. He's the tall, dark fellow over there. You're surprised to see him here because of his clean look. No matter what Hickey says about me, he's talking through his hat."

"You'd rather be talked about through a hat than a loud-speaker," said Hickey. "Run along, Elspeth; it's wonderful how you keep your face, win or lose."

The girl smiled at Ryder and moved away.

"She's quite a nice person, at that," said Hickey. "All that keeps Elspeth from the domestic virtues is about five thousand a year—which is not enough.... That's Marene Sutherland, over there. She's just a shady bit older than the rest of them. Your uncle can tell you more about her than I can and, as for the details of her private life, just now, that lies between J.J. Leggett and J.J. Leggett. Or do I see a question in your eye?"

"Not about her; but that very beautiful girl—who is she?" asked Ryder.

"I intended to crown the glory with her," said Hickey, "but no one is speaking out of turn in mentioning Leslie Car-ton. I suppose you recognize her?"

"Recognize her? No."

"You have been away from the States," said Hickey. "Just now she's better known from the tips of her toes to the shine of her hair than anything this side of Hollywood. One of the smart magazines printed a picture of her that's been copied in every rag in the country. Haven't you really seen it? Look here!"

He drew out his cigarette case. His thumb held, behind the platinum, a picture of a girl in a bathing suit.

"Walking the waters," said Hickey, chuckling.

In fact, the girl seemed to be springing over the face of the sea and the speed of her running pressed back her hair as with two hands.

"She's more dressed in light than in clothes," said Jimmy Hickey. "The silk of a swimming suit doesn't matter, once it's drenched. You see, she was aquaplaning and the plane jumped sidewise from under her feet; at that lucky instant when her foot touched the water, the camera got her."

"And the person who took the picture sold it to a magazine?" asked Ryder coldly.

"Art for art's sake, and a few dollars added," said Hickey. "But a light like Leslie's shouldn't be hidden under a bushel. A year ago she had never seen New York; now most of New York has seen her. She has a liberal nature; at least I don't know of anyone who has had to pay for her so far."

"You don't mean that, I think," said Ryder, with disgust.

"Oh, I've only been giving you the headlines, but if you want facts, I can give you a lot of news, also."

"I'd better take that for granted," said Ryder.

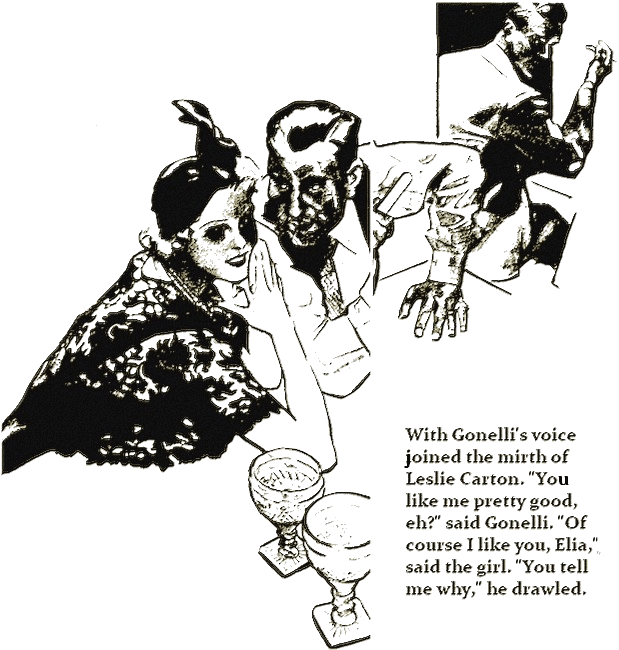

"The fellow with the magnificent forehead is Porter Brant, the great producer and fathead. He wouldn't be here; he wouldn't be anywhere except for Sydney Galloway. She's that perfect profile, over there. The dark, sleek fellow who's trying to make love to her is Eric Claussen, but his wife pointed him out before. He knows enough about horses to make money at the races; some people say that that's too much knowledge for an honest man to have, but I've cashed in on some of his tips so I still speak to him. There, just sitting down on the arm of Ravenna's chair is Millicent, the Countess Lalo. She's every man's little girl and she'll ask your advice before the evening's over. She's one of those clinging vines that cost you your skin before you can tear the tendrils loose. And I guess that's everybody except the little singer, over there, Eileen Durante. The quiet girl. Studying singing. Has a sweet voice about as big as a minute. A sweet nature, too. I don't know why Leggett should bring her in among all these roisterers except that he's so crazy about old gold. Notice that? All six of them have golden hair.... Now, do you remember anything I've told you?"

"I forget easily," said Ryder.

"Good fellow!" answered Jimmy Hickey. "I knew I wasn't wasting my time on you! Come along while I introduce you... bring your drink."

He took Ryder to Leslie Carton last of all and said: "He picked you right out of the whole ruck, Leslie, just on your face. Be kind to him. He's a swift and bitter fellow; the type that loves once and loves forever."

"Don't let Jimmy Hickey bother you," said Leslie Carton. "The difference between Jimmy and a rattlesnake is that he doesn't give any warning before he strikes."

He looked after the departing figure of Hickey, who walked with a sort of sidelong aggressiveness, as though he were thrusting through a crowd.

"The little rat was showing me that picture of you," said Ryder.

"I knew he was doing that," she answered, and though her eyes had seemed bright enough before, a shadow withdrew from them now and seemed to give him a deeper entrance.

"There's this advantage," she said. "After Jimmy has talked, you know the worst."

Claussen joined them to say: "What's happened to John Leggett tonight? There's more fire in the eye than I've seen in him since Dorrie disappeared."

"I didn't know you all in Dorrie's time," said Leslie Carton, "but John looks to me like a small boy with a secret."

Ravenna said in his great, booming, gonglike voice, as he got into his coat and picked up a glass: "All my friends—before we go into dinner, let's drink to the other girl. Someone has just spoken her name. God be kind to her wherever she is.... To Dorrie!"

They all drank.

"Who is Dorrie?" asked Ryder.

"A girl who disappeared a year ago," said Leslie Carton. She had stopped smiling and looked down studiously at her cocktail. "Simply dropped out of sight. I never saw her but they all adored her."

They were going into the dining room now.

"Her name is the only thing in the world that can sadden them," said Leslie. "She must have been quite a darling. I've seen tears in the eyes of Jimmy Hickey, even, because of Dorrie. It's the only reputation in the world that he doesn't poison."

"Why do you have him about, then?" asked Ryder.

"Because it's fun to play with fire," laughed Leslie Carton, but her laughter broke on an uncertain note. He had an impression that she alone of the entire group was profoundly ill at ease.

When people found their places, Ryder was sitting with Eileen Durante on his right and Leslie Carton on his left.

"Look! Look!" cried the hearty voice of Mrs. Eric Claussen. "Everybody see my favor!"

"We all have the same thing!" exclaimed Sydney Galloway, and all six of them held up little golden angels an inch and a half tall, carved with grave Egyptian faces and inlaid wings rising stiffly above their heads.

"Are they really favors? Do we really take them?" asked Elspeth Claussen.

"You really do," said Leggett. "Because this is an evening I want you to remember."

"But why is everything so perfect?" boomed the resonant voice of Mike Ravenna. "All this polish hurts our eyes, John."

"I wanted this dinner to be perfect," said Leggett, "because it's the last time that I'll see you all together."

"The last?" chorused many voices.

"The last time that we'll all be together," said Leggett. "There's going to be an absentee the next time. I have a messenger on the way now, bringing me the proof in pictures and in writing that one of you good friends of mine has stabbed me in the back. Don't let me upset the rest of you. The guilty one will do the suffering. After dinner, I hope that I'll be able to give you the name along with the cognac."

There was a quick, whispering intake of breath all around the table. A tremor of light on the glass which Leslie Carton was fingering made Ryder glance at her. Every other face was grave but she still forced her lips to smile.

That brutal announcement by Leggett would have ruined almost any party and probably the good humor in this one could not have survived except for Mike Ravenna exclaiming: "Perhaps John is thinking of my sins. I've got enough of 'em. But my heart is floating right among the terrapin. Leslie, say something to cheer us up."

"Maybe nobody's head will go off except Jimmy's," said Leslie Carton.

The people laughed at this, except John Leggett, who kept looking straight before him at his nephew and seeing nobody. Eileen Durante lifted her big eyes at Ryder and said: "It's all just a joke, isn't it? Nothing will really happen, will there?"

"Of course it's just a joke," answered Ryder, but he felt a gathering suspense.

There was plenty of wine, particularly a priceless Romanée with a bright jewel in the heart of it. Most of the people drank a good deal and presently Ryder managed to make out the insidious voice of Jimmy Hickey saying to Marene Sutherland: "After all there ought to be a good party when the fatted calf comes home."

"Don't be nasty about him," said Marene Sutherland. "David seems nice."

"That's one of your pleasant maternal attributes, Marene," murmured Hickey, "you're so devoted to the young."

Ryder caught the rather apprehensive eye of Leslie Carton and smiled at her.

"My time to burn a bit in the fire," he nodded. "Or should I trample it out?"

"That doesn't seem to do any good," she answered. "Men have hammered him to pulp before this."

"Why does everybody seem guilty?" Ryder asked her.

"Because we haven't paid our way with John, for one thing," she answered.

"You mean that he's a great entertainer?" suggested Ryder.

"Yes," she answered.

"And so people pretend to like him a little more than they really do?"

"He wants real human beings," said the girl. She looked at Ryder and flushed, so that he suddenly realized that in this century only tennis and cocktails make girls blush. "He wants to have real people around him, but he only has a lot of bright chatter and pretty girls."

"But that big, hearty fellow, Ravenna...." suggested Ryder.

"Perhaps," she agreed. "Perhaps he's different, or perhaps we're all wrong. Do I seem guilty, too?"

"I don't care whether you're guilty or not," said Ryder.

Her eyes took note of him but she said nothing more. He had to turn to Eileen Durante. In contrast with the warmth of Leslie Carton, she had the impersonal quality of a lovely child. Whenever she spoke she smiled and whenever she smiled she opened her eyes a little so that she kept shining and dimming and shining again as she talked.

"I've heard about your singing," he said.

"I sing a little," she answered. "I'd like to sing a lot but—you know, there's not a lot of me, is there? It's only a small sort of a voice but voices sometimes grow like the rest of us, don't you think so? I sing duets with Mike Ravenna and that's very nice except when he forgets and goes booming."

She laughed and shook her head.

"Did you know Dorrie?" he asked.

"The air here seems to be full of her name."

"Dorrie? Oh, yes. No one in the world ever was as sweet as Dorrie. Sometimes we used to sing together but then, of course, nobody paid the least attention to me."

"She disappeared?"

"Isn't it a frightful thing? Isn't it dreadful? She was going to meet Porter Brant and some of the rest one evening after the theater and she didn't come. She just didn't come!... And that was all that we ever heard about her.... Leslie Carton lives in the same room that Dorrie used to have. Isn't that a strange coincidence?"

"That is strange," said Ryder to Leslie Carton. "That you should have taken the same room that Dorrie used to have. Dorrie was her name?"

"Dorrie Innis. Having her room is how I happened to meet some of these friends of hers."

Brant's voice, loud, strident, interrupted them: "I want an opinion from everybody. I've been talking with Harry Weinstock, of Weinstock, Ruhl, and Klosterberg. He's seen the picture of Leslie Carton and he says that she's a natural for any picture I want to direct her in. But when I put the thing up to Leslie, she declined. I told her the sky was the limit, but the sky seems a pretty low ceiling to her. Now I ask you all... what is the duty of a beautiful girl? Has she the right to keep herself from the eyes of the world?"

Leslie Carton smiled.

"Porter offers me a lot of Weinstock money," she said, "and practically no wardrobe at all."

The table laughed.

"I imagine he wants to put you in a South Seas story, doesn't he?" asked Ryder.

There was more laughter. Hickey said: "Look at Ryder, Leslie. He's really angry. Look out for yourself. I've an idea that he's decent enough to be dangerous."

Ryder felt her look suddenly up at him and that her color had deepened a little. The sneer of Hickey passed him by. He could have blessed the venomous little man, for it was sufficiently plain, now, that the cosmopolitan nonchalance of Leslie Carton was only assumed.

One of the servants came in and murmured at the shoulder of the host. The dinner had come well to an end and Leggett stood up.

"I have to see someone in my study," he announced, "to receive very special information about one of you."

As Leggett stood up, the others began to rise. He rested the tips of his fingers on the edge of the table, looking around the oblong of faces with a grin.

"We haven't eaten as well as we do at Mike Ravenna's house," said Leggett, "but Mike wears us out at the table and I wanted to keep some of your attention for the little story I'm going to tell you later on. The story is in my office now waiting for me in black and white that will be poison for one of you. I'll soon be able to tell you who it is. Mike, will you take charge of the men for a while; and you do the same for the ladies, Elspeth?... David, let me speak to you a moment."

Even when the club was flourished over the heads of the guests in this manner the second time, their chatter continued as cheerfully as ever. As Ryder went to his uncle he heard Jimmy Hickey saying: "I suppose he'll expose me; but what do I care about scandal? You can't kill a salamander with fire, you know!"

Then Ryder got to Leggett and found him with a wine-flush in his cheeks and a gleam of excitement deep in his eyes.

"You're finding Uncle John a darned rough fellow, even with guests in his own house, eh, David?" asked Leggett. "But before I go to see my bird of evil, tell me something: Which of your neighbors would you choose, my lad? What does the old prophetic instinct say to you about Leslie Carton or Eileen Durante?"

"I'm too young to love children," said Ryder. "But Leslie Carton is different."

"The hell she is!" exclaimed Leggett in unaffected disgust. "Well..."

But he turned on his heel without more words and went quickly out of the room. On the way, Claussen called after him: "No more bad news from the street, John: not that, I hope!"

Leggett disappeared without an answer and Claussen picked up Ryder to say: "He's been losing his shirt. I suppose you know that? The great open spaces are the place for your uncle, where he can dig it out of the ground."

During this time and the moments that followed, the tragedy happened. There was a good deal of movement through the rooms. The groups which formed dissolved again. The men went about streaking cigar smoke through the air; the women rustled upstairs and down; so that no one, afterward, was able to swear to exact times and locations.

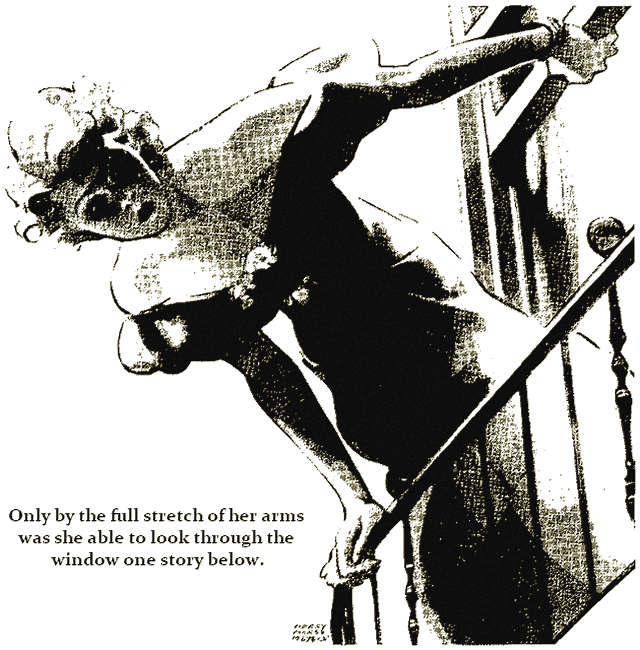

Gains, during this interval, saw Leslie Carton go into the drawing-room, stare for an instant at Tiepolo's picture of a gondola loaded with Venetian youth and beauty, and then hurry down the hall toward the office. He did not see her a little later when she ran up two flights of stairs and opened the door of an unlighted room. She closed it behind her without turning on the switch and felt her way through the blackness until her hands touched the soft pelt of a velvet curtain. Under it was the damp cold of the window pane. She found the catch, turned it, and pushed the window up with such care that it made not the least sound. Afterward she leaned out and looked to the left, but a row of little ornamental balconies blocked her view. She hesitated there for a moment. Then she took off her slippers and climbed out onto the narrow balcony. It had no guard rail to speak of and the wind leaned a hard shoulder against her dress, as against a sail. She had to take a grip on the partly raised sash of the window to anchor herself as she swayed far out. Only at the full stretch of her arm was she able to look through the window one story below, where the wall of the penthouse made an angle.

If the shade had been all the way up, she could have seen much more but as it was, all she could make out was half the body of a man stretched on the floor and another figure leaning over him. Instead of framing this picture, the edge of the window cut off the vital portions of it; she could not see the head or shoulders of either man. The man who lay on the floor did not move. A high- light blazed steadily on the toe of one of his patent-leather shoes. The pull on her arm made her muscles tremble and her fingers began to slip on the window sash, but she held her position long enough to see a hand slip inside the coat of the fallen figure and take out a long envelope edged with the red, white and blue checkering of the air mail. After that, she climbed back through the window, found a chair, and sat down in it while she pulled on her slippers.

She drew down the window, let the curtains fall together with a soft whisper, and in the black of the room retouched her hair into shape. With her memory she tried to light again the scene which she had looked down upon. It was like seeing the faces of actors without being able to hear their spoken words. The legs of the fallen man were quite long. Above the knees the flesh, pressing against the floor, filled out the trousers smoothly. He had a good deal of bulk about the waist, too, and the picture in her mind's eye was of a tall, heavy man. The figure that stooped over him was big, also, but there was a suggestion of greater youth about it. If she could have looked one foot higher into the picture she could have seen everything, but the window shade beheaded the image.

She went over the hem of her skirt to brush away any possible dust from the chiffon. Since she wore no make-up except for lipstick, she rubbed her cheeks to freshen their color before she made her way to the door and out, briskly, into the hall. All the way downstairs she walked slowly, breathing deeply to bring nerves and body under control.

David Ryder, running up the stairs with the effortless spring of a hurdler, encountered the girl at the landing. He sidestepped to let her pass, murmuring some vague greeting, and he noticed two oddities as she went by. The first was something strange about her smile. The strangeness lay in her failure to lift her eyes to his face as she smiled. Women leaving a theater are apt to talk and smile in that manner with lowered eyelids, so that their tears may not be seen. Also, the ruby pendant just below the hollow of her throat trembled into a blur of rosy light and he knew that her whole body was shaken by the wild beating of her heart. Ryder noted these symbols of emotion in the instant of passing the girl. His hand went out in a tentative gesture that stopped her.

"Something wrong?" he asked.

She shrank from his hand. As her eyes flashed up he saw the pupils dilated by fear into the true blank and mindless stare of terror.

"Nothing..." she started to say, and glanced up the stairs, shuddering.

"You don't mean that someone is following you?" he asked.

He put his foot on the next step but she shook her head.

"Don't talk, then," said Ryder. "Sit down here."

There was an Italian stone bench near them. When Ryder got her to the bench she slumped down on it.

"I'll get a cognac to you in ten seconds," said Ryder. "Don't move..."

"No... stay with me!" she whispered.

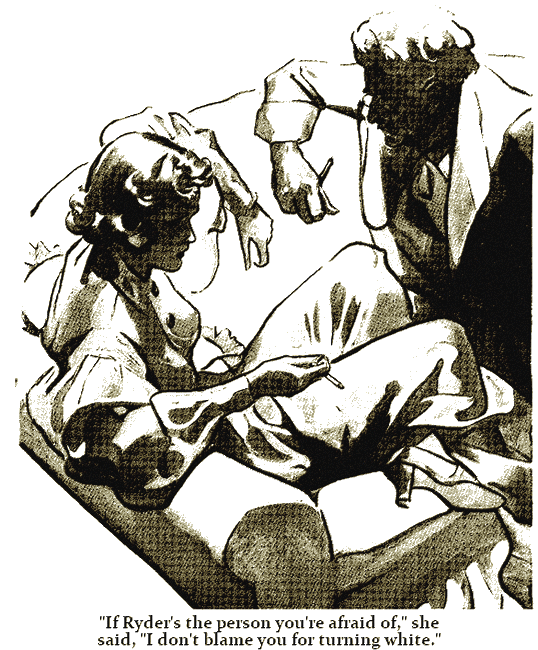

Her head inclined to one side with weakness and Ryder dropped to his knee beside her.

Eileen Durante, passing through the hall below, glanced up. She paused to study the two figures on the bench with those wide, clear eyes. Then she went on.

"Make me stand up," murmured Leslie Carton.

Ryder took her under the elbows and helped her to her feet. She drew in a greater breath.

"Lean on me a moment," directed Ryder. "You're better. Your color's coming back and the shudder is going out of you.... Can you tell me what's wrong?"

She could not speak. The lights in her eyes kept changing.

"Don't bother, then," said Ryder. "I'll ask no questions. I'll not even think a question."

"Thank you," said her lips, with only a ghost of a voice upon them. She was mastering herself like a man, growing taller, and the pendant at her throat gleamed with a steady eye as her trembling stopped.

"I mustn't be gone from them long," she said. "Do I seem all right now?"

"You're better every moment. But don't go yet."

"I'll try to smile.... Does that cover things up a bit?"

He did not reply.

At last he said: "I'll take you down,"

"No. I'll be stronger if I go alone," she told him; and then, laying a hand on his arm, she added: "How kind you are!"

His own action surprised him. Of course he had lived in Europe so long that he had picked up some of their manners, yet he was amazed to find that he had lifted her hand to his lips.

She went down the steps and paused once, looking back with a faint smile as though already she missed the strength of his support.

Afterward he hurried on to his room but when he reached it he forgot what he had wanted. He gripped the back of a chair and leaned his weight on it and tried to think but his brain kept whirling. The very air that he breathed lacked something that was vital to his existence. After a moment he realized that it was the perfume she wore, a clean, delicate fragrance, and he knew then that he never would forget it, for the thought of her was qualifying the very breath of life.

He went down to the library and found that he was the last one in. They stood about in groups except for the childish figure of Eileen Durante, who was prodding the logs in the fire-place to a flame that really was not wanted for warmth. Huge Mike Ravenna stood over her with his laughter rumbling. Jimmy Hickey sat on a deep couch between Countess Lalo and Elspeth Claussen. Marene Sutherland stood by the long, ponderous Italian table talking very earnestly with Sydney Galloway, who looked pale. Eric Claussen sat by himself, with his chin on his hand, and Porter Brant was pouring the last of a powerful brandy and soda down his throat, while Leslie Carton chatted and laughed beside him. Ryder, apart watched them all, and had one deep moment for wonder at the cheerful color in Leslie's face.

Martin came in, looking out of place in his sack suit. He went straight to Ryder, not forgetting his manners and his bows to ask pardon for the intrusion as he crossed the room. Then he was saying close to the ear of Ryder: "Will you come at once, sir? In the study... your uncle is..."

The thin, sallow lips of Martin trembled over the words. He choked, the Adam's apple working up and down in his scrawny throat. Ryder went out of the room with him instantly. In the hallway he said: "Now what's the matter, Martin?"

The valet turned his head, making a gesture with both hands that seemed to proffer an explanation, but he said nothing as he opened the door of the study.

From the threshold Ryder saw John James Leggett lying on the green rug beside the desk, smiling a little with half-open eyes and a bullet hole in his temple. In his right hand he still held an automatic.

SOME of the years which are marked down one by one between our eyes had been rubbed from the forehead of Leggett by death, so that he seemed to Ryder not elderly but in the middle of his prime. Martin, with both hands still extending to show the monstrous thing to the world, stood half a pace inside the door and kept looking back at Ryder with wild eyes.

"Don't be an emotional damned fool," said Ryder.

Martin, shuddering, dropped his hands and stood straight again. He watched the face of Ryder and nothing else with a profound, continuing hate.

"Suicide, eh?" asked the calm voice of Ryder.

"No!" cried Martin.

"The gun in his hand, the powder burn around the bullet hole."

"Murder, sir," said Martin.

Ryder drew out a handkerchief and took the polish of sweat from his forehead.

"Stop shouting," he commanded. "One of the servants, do you think?"

"Impossible!"

"Have you telephoned the police?"

"Yes, sir."

"They'll call it suicide but you and I think something else.... One of the guests?"

"Yes, sir," Martin said emphatically.

"Come back with me to the library. I'm going to announce this and I want you to help me watch the faces. Have you got the fog out of your eyes?"

They returned to the library, where Ryder halted a step inside the door with Martin just behind him. Ravenna, nearing the end of an anecdote, had the others already nodding with expectant laughter. The still figure near the door stopped the booming of his voice; and all eyes settled on Ryder.

He said: "I'm sorry to shock you but you have to know. Mr. Leggett has just shot himself and is lying dead in his study."

The people who were seated got up slowly, one by one. Out of the silence, the big voice of Ravenna rang suddenly:

"John? Gone from us? My God!" and he lunged for the door with his hands out as though the grasp of them still might hold a soul on earth, if only he were quick about it. Everyone followed him like leaves drawn into a great wake, except Millicent, Countess Lalo. She dropped back onto the couch from which she had just risen and rolled from the edge of it to the floor with her arms loosely thrown above her head. Ryder, scanning every face, saw the countess open her eyes slightly to peer after the rest, and then close them tight.

Ryder stopped that exodus at the last moment by calling out in a loud, harsh voice: "Everyone stay in here, please."

They piled up in confusion for a moment but gradually gave back before his authority. Only Mike Ravenna caught him by the arms and muttered: "I've got to see John, David! I've got to see him. Let poor Mike go and see him."

The sweat streamed down the face of the fat man so rapidly that he seemed to be weeping. Ryder answered: "Just take care of things in here for a while, will you?... You might give some attention to the countess, if she's still trying to faint. The medical examiner will be here before long and then, of course, everyone can go home."

He closed the door of the library; a woman whose voice he could not identify began to cry out as Ryder went to the study with Martin. On the way he said: "Did anyone hear the shot, Martin?"

"The study is soundproofed, sir," said Martin. "It has a triple window, even. Mr. Leggett did not set aside much time for thought but when he worked he would not be disturbed."

"You watched their faces in the library, just now?" asked Ryder. "How did they look to you?"

"Like a string of fish hooked on one line," said Martin.

"But I mean... even young Miss Durante?"

"I gave her an eye. Yes... even her," said Martin. "And the countess that decided to faint, too."

"Guilty?" growled Ryder. "It's as though you'd asked nine fish which one was wet."

Martin, opening the door of the study once more, picked up a newspaper on a chair near the entrance and began to lay out news sheets on the rug at convenient stepping points.

"In case the police should be annoyed if the footprints were blurred," explained Martin, "by a great deal of later trampling."

"Footprints? In a rug?" exclaimed Ryder.

Martin said: "The police work with camera eyes and laboratories now, Mr. Ryder."

"Well, that's true," said Ryder.

When he reached the body, he put his hands on his knees and leaned over it. The half-open eyes looked steadily back at him. A big, purple-black powder-burn surrounded the hole in the right temple. There was a larger opening on the opposite side of the head. The right forefinger of Leggett still engaged the trigger- guard of the automatic.

"Well?" said Ryder, straightening.

Martin pointed to the open drawers of the desk, the confusion of papers.

"What about the man who called here to see my uncle?" asked Ryder.

"Tall, no forehead, a big, hanging jaw, a huge nose," said Martin.

"The police will want to know that," said Ryder.

"The man left while Mr. Leggett still was alive," answered Martin. "Gains saw him out, and saw Mr. Leggett standing at the door."

"He brought a message about one of the guests tonight," said Ryder. "But perhaps the message had something to do with my uncle, also. Enough to drive him to suicide?"

"Never!" said Martin.

"He simply allowed another man to put a gun against his head and pull the trigger? That's absurd, Martin. My uncle was a pretty lively fellow. He could not have been shot except from a distance."

"SUPPOSE he had no suspicion?" asked Martin.

"What?"

"Well, a woman? Perhaps in his arms, sir? She lifts the gun out of that top drawer and puts it against his head."

"Is it his gun, Martin?"

"Yes, sir."

"It's suicide, Martin."

"No, sir."

"What makes you sure?"

"I know him, sir."

"How long have you been with him?"

"Three years, sir."

"That's not very long."

"More than a lifetime with another man, sir."

"Murder, eh?" said Ryder, dropping to one knee and one hand, close to the body. Something cold touched his finger at the edge of Leggett's sleeve. He pulled out one of the six golden angels. His hand swallowed it instantly from sight. He rose and slipped the token into his pocket. The bright eyes of Martin haunted his face constantly.

"I'll see Gains," said Ryder.

He saw Gains in the pantry. The butler breathed thick brandy fumes on Ryder as he stood up.

"You saw the fellow leave my uncle's study, Gains?" asked Ryder.

"Yes, sir," said Gains.

"You had a look at my uncle at the same time?"

"Yes, sir. He seemed all right. A little grim, perhaps. The stranger was only in the study for ten seconds."

"What did he say?" asked Ryder.

"Nothing at all. He didn't speak all the way out to the elevator," said Gains.

"Nothing else to tell me?"

"Nothing, sir."

Ryder said to Martin: "See that none of the women leave the library."

"The women, sir?" said Gains. "Why, they've gone just a moment ago. Mr. Brant told me to show them out."

"Gone?" cried out Ryder.

He got to the library as fast as he could and jerked the door open. The four men were sitting on the couch, talking with a quiet earnestness, and they jerked up their heads as Ryder called:

"Ravenna, I asked you to take care of things in here. What the devil does it mean—the women leaving?"

Porter Brant stood up and took advantage of all his height. He said: "My dear young fellow, a gentleman doesn't make the ladies uncomfortable when...."

"Ah, but, David... was it wrong?" asked Mike Ravenna, coming toward him with his hands outstretched.

"I don't know," said Ryder. "I hope not, of course. But who the devil suggested that they go?"

"I did," said Porter Brant.

Ryder got himself out of the room and found Martin in the hall.

"Send six messengers," he commanded, "to the women who were here; give each messenger a note saying that I beg them to return the dinner favors they received tonight. Say that it's very important. You understand? The six golden angels that were by their plates at dinner. Do that on the jump."

The inspector, a silent man with the look of a weary old tiger, sat and twiddled his thumbs until he had the report of the medical examiner. That report was brief. The doctor said: "Leggett shot himself."

The inspector, who had listened without comment to Ryder's story, said: "Perfectly simple. The man he saw in his studio brought him bad news. Find that man and we can learn why Leggett killed himself. That ought to be simple. Nothing more to tell me, Mr. Ryder?"

"Nothing more," said Ryder, gripping the golden angel in his pocket.

"Goodby, then, Mr. Ryder," said the inspector. "My condolences to you, and all that."

The law had finished. The newspapers had only begun.

"How many reporters are out there?" asked Ryder of Martin.

"They and the photographers are still coming," said Martin.

"Ask Mr. Ravenna to speak to me in the study," said Ryder. "And tell the other three that there's nothing to keep them in the house any longer."

"In the study?" repeated Martin.

"That's it," said Ryder.

He sat down in the big chair behind the desk and lighted a cigarette just as Ravenna came in.

"The air outside is full of newshawks and buzzards," said Ryder. "Will you go talk to them, Ravenna? They know you well enough to listen to what you say."

"I'll go," said Ravenna.

He dropped down on one knee with a lightness amazing for his bulk and took one hand of the dead man. The sweat kept distilling from the green-gray of his face and Ryder watched the running of every drop. He allowed the silence to continue for a moment like a quickening stream. Then he said: "Tell them that I'm prostrated by grief and can't see anyone; tell them financial worry about the state of the market undoubtedly preyed on the mind of Mr. Leggett."

Ravenna crossed himself and stood up.

"I'll talk to them," he said, turning to the door.

Ryder got there before him and grasped the huge, soft hand.

"I thought you were real before," he said. "I know it, now. You loved him, Mike, didn't you?"

"Loved John?" echoed Ravenna. A smile twitched at his face and shook it like a stiff jelly. "But why did he do it?"

"He didn't. It was done for him," answered Ryder. "There's the why of it. In that desk a few days ago he put a new will leaving everything to me. You see the drawers open now? There's no use searching through them. The new will won't be found."

"Murder? D'you mean murder?" whispered the Italian.

"Everybody in the house had a chance to come in here after dinner," said Ryder. "You and I along with the rest."

"But a man who carried his purse in his hand—who never refused—" said Ravenna.

When he had finished his gesture, he shook back his shoulders and said: "There's another matter, speaking of money. Whatever you get from the estate won't be in your hand for some time. You'll need cash in hand, David, and here's my check for some running expenses."

He took out a checkbook and wrote out a check for ten thousand dollars. When Ryder tried to thank him he brushed the words aside as he murmured: "But murder, David? Who in the name of the kind God could have borne malice toward John Leggett?"

"He had too much money," said Ryder. "Every rich man has murder in his bank account. If he's stingy, people will kill him to get at his wallet. If he's generous, it shows how much cash the murderer can get. If he'd missed his luck in Canada, he'd be alive now."

"Is that it?" murmured Ravenna with a sort of helpless acceptance.

He turned slowly from the room and went down the hall.

Gains helped Ryder take the dead man into his bedroom and there Ryder sat in the dimness before an open window, with his arms folded. Ravenna came back to him after a time and said: "Shall I make the arrangements, David?"

"Will you?" asked Ryder. "And have everything quiet, Mike."

Ravenna left but Martin presently called softly from the hall: "We have the answers about the golden angels, sir," and Ryder went out to speak with him, holding out his hand.

Martin gave him three envelopes.

The first said:

Dear Mr. Ryder,

I don't know what you have in mind, but please don't ask me to give up my only souvenir of Mr. Leggett.

Faithfully yours,

Sydney Galloway.

The second, in a different vein, said:

Dear David Ryder,

I started to send out the little golden angel and then when I looked at its face it seemed to beg me not to let it go. So I've kept it. Do you mind? Terribly?

Cordially yours,

Millicent.

The third, from Eileen Durante, told him:

Dear Mr. Ryder,

Do you really want it? I read your note over again. And then I knew that it couldn't go back by a mere messenger. But if you have to have it, I'll bring it myself, whenever you say the word.

"Here are three answers," said Ryder. "What about the rest?"

"Mrs. Claussen slammed the door in the face of the messenger after she had said 'No.' Marene Sutherland was completely prostrated and could not be seen by anyone. Miss Leslie Carton was not at home."

"Not at home?" demanded Ryder.

"Not at home, sir."

"It doesn't matter," said Ryder. "From the whole six I collect a zero. What do you make of that, Martin?"

"The American woman is a person of high spirit, sir," said Martin, and bowed so low that his face could not be seen.

Ryder sent Martin to bed and went back into the room with the dead man to sit again long enough to mark the slow drifting of the stars in the sky. Afterward he stepped into the hall to listen to the house and savor the air, then he passed the circling well of the stairs to the study and pushed the door open.

As though the edge of the door had knocked a spark out of the darkness, a faint bright streak that might have been an optical illusion crossed his eyes. He shut the door softly behind him. He found the light switch at the right but before he turned it, he squatted on his heels.

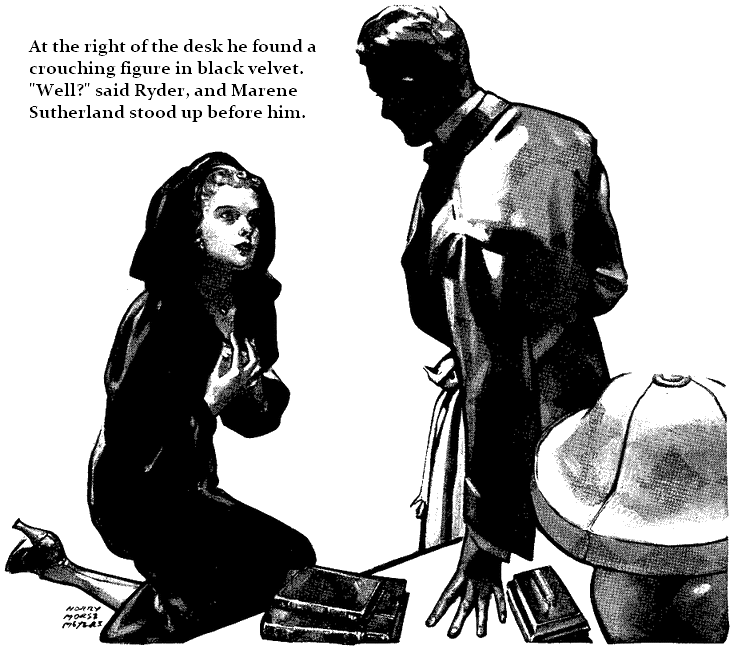

The flare of the lights showed him nothing except the polished gleam of the desk and the meadow-green softness of the rug, but a thin fragrance hung in the air and it was this that made him stand up and stalk the desk with care. At the right of it he found a crouching figure in black velvet.

"Well?" said Ryder, and Marene Sutherland stood up before him. The velvet hood slipped away from the crumpled red-gold of her hair and in the hollow of her throat a short emerald pendant trembled between dark and bright.

"Sit down," said Ryder.

She fumbled for a chair and slid into it without taking her eyes from him.

"I'm not going to call the police. Do you want a drink?" asked Ryder.

"No," she whispered.

He offered a cigarette, which she took without being able to drop her eyes from him.

"When you feel up to talking, say so," remarked Ryder, and began to walk up and down the floor, his steps making a hushing sound on the thick of the rug.

"I'll try now," said she.

He stamped out his cigarette in an ashtray and sat on the edge of the desk, looking down at his folded hands.

She said: "I had to come back. There's something here that John wouldn't have wanted anyone to find."

Ryder did not move or speak until the silence had a pulse in it. Then he remarked without looking up: "I don't want to make this hard for you; and I can't tell what questions I should ask. Take your time. Are you sure you don't want a drink to brace you?"

"Will you look at me?" she asked.

He lifted his eyes and she shrank from them but then steadied at once. Her fingers busily strangled and smoothed and strangled again a little velvet purse.

"There's a diamond bracelet," she said. "He gave it to me... then things went very badly and I had to ask John for more help... he gave me the help... but he said that I had to be more businesslike... and he took back the bracelet when he gave me the loan because he said that I would have to leave it in pawn until... until..."

She was unable to talk any more. Her eyes took a frightened desperate hold of his.

"Then I think we'd better find the bracelet, don't you?" said Ryder.

She cried out; "Do you mean it, Mr. Ryder?... Everybody would recognize it. And if it were found among his things...."

"We don't want that, do we?" asked Ryder. "Ordinary gossip is bad enough but printed gossip kills a man's reputation; they'd print this. You start on the right-hand drawers and I'll start on the left."

He made a good deal of noise rustling the papers but not sufficient to cover the sound of her panting and then a gasp as she started up with an old brown leather case between her hands. When she opened it, the whole inside was a white welter of fire. She held it for him to inspect the incrustation of big brilliants but, instead, he looked only at her begging eyes.

"If I were you, I'd take it right home," said Ryder.

"Do you mean..." she gasped.

"It's all right," said Ryder.

"God bless you!" cried Marene Sutherland.

"I could do with a blessing or two," smiled Ryder. "Shall I see you out?"

"Wouldn't it be better not?"

"I'll stay here, then. By the way, do you happen to have that dinner favor, the little golden angel, with you?"

"I left it at home. I'm so sorry. Do you want it?"

"It doesn't matter. But how did you manage to get into the penthouse?"

"You know—I have a key—"

"Oh, have you?" asked Ryder. "Well, that explains. Good night."

She took the hand he held out and said: "I wish... I wish..." Then she fled away into the hall.

Ryder turned out the lights and sat down behind the desk again. He rested his face on the flat of his hand, blinding his eyes; but when he tried to think, a thousand pictures and sounds poured back over his memory. The jerk of his head as he nodded into sleep roused him again, guiltily, with a sense that time had slipped suddenly past him. He had reached for a cigarette when that glint of light on the knob of the door went out; the door opened with a gradually sighing sound; and the lights were snapped on by tall Eric Claussen with his topcoat open and his silk hat tilted far back on his head.

The sight of Ryder knocked the breath out of him with a grunt. He jerked out a heavy old army automatic with a suddenness that made his whole body crouch, and his long face twisted as he sighted down the barrel.

"Get your hands up, Ryder," he directed. Ryder lifted them as he rose from the chair.

"Out here away from the desk," said Claussen.

Ryder stepped out into the center of the floor.

"Go ahead with the desk, if that's what you want," said Ryder. "Nothing of mine is in it."

"You're the new generation, calm and cool and sure, eh?" said Claussen. "I'd like to tell you what the older generation think of the young rats that crawl around the face of the earth today."

"But you're not so old yourself, are you?" asked Ryder. "Not much over thirty. Not very much, are you?"

"I don't know just what I'm going to do with you," said Claussen, "but I'll register a few points before I decide. I want to speak about your high head and the sneer you carry around with you. D'you think that looks European and distinguished? It only makes you a pain in the neck. Are you getting this? In the company tonight you looked like a selling plater with stake horses."

"Yes, I thought you were all running for money," nodded Ryder.

"You thought we were what?"

"You're about thirty-two and a hundred and ninety pounds." said Ryder. "You're not too old and you're not too small for me to hit, so here it is, Claussen."

He stepped in with his left foot and dropped his right fist on the chin of Claussen. The automatic jerked up, but without exploding. Ryder hit again with the same hand, a little straight, stabbing punch. Afterward he took Claussen under the armpits and dragged him to a chair into which he allowed the long body to slump. The silk hat did not fall off but leaned at a drunken forward angle. Ryder picked the gun out of nerveless fingers. He stooped to look at the unseeing eyes, then left the study, locked the door on the outside, and went upstairs to Martin's room.

When he entered and turned on the light, Martin sat up in bed and reached under the pillow.

"It's all right," said Ryder. "I have a guest downstairs that I want you to talk to. Put on slippers and a bathrobe and come along."

A niche had been hollowed into the wall and in the niche hung a gilded crucifix. Ryder glanced at the tortured body before he stepped into the hall to wait. Martin came out almost at once, smoothing down a forelock.

"I have brought a gun, sir," he said, looking at the weapon in Ryder's hand.

"Oh, this thing?" said Ryder, with a casual start. "Take this, too. We won't be needing guns.... The poor fool left the safety catch on. A grown man, too, Martin. Otherwise the police might be wanting him for murder."

When he unlocked the door of the study, Martin said: "Let me go first, sir!"

But Ryder shook his head and thrust the door open. Claussen, half hanging out the window, jerked himself back into the room as the two entered.

"Our friend Claussen, as you see," said Ryder. "Tell me about him, Martin, will you?"

"Is that a command, sir?" asked Martin.

"Absolutely," answered Ryder.

"Oh, damn all this," broke out Claussen. "I want five minutes alone with you, Ryder."

"I don't think you'd last that long," said Ryder. "But go ahead, Martin. Tell me about this fellow, will you?"

"I beg your pardon, Mr. Claussen," said Martin.

Claussen snatched a cigarette out of the tray on the desk and lighted it. Martin began: "Mr. Claussen is a very talented man. He is a mind-reader, sir. He can tell by a face what woman will lend him money and which jockey can be bribed to pull a horse. So he gets on very well in the world, of course."

Claussen, breathing out a great volume of smoke, barely glanced at Martin.

"Do you want to hear this sort of dirt?" asked Claussen, "or will you talk with me alone?"

"I don't want to be alone with you, and I don't think you want it, either," said Ryder.

"You're talking about that other thing, eh?" said Claussen. "Why, that was sheerest bluff, of course. The safety catch was on the entire time."

"You remembered that afterward," nodded Ryder. "Go on about him for a moment or two, Martin. I want to know what dealings he had with my uncle."

"Mr. Leggett made certain mistakes about people," said Martin. "This was one of them. He was beginning to pay for the mistake before the end. A few days ago he sent a very crisp note to Mr. Claussen asking for an immediate payment of some old debts."

"A lie, of course," said Claussen.

"How do you know that?" asked Ryder.

"I delivered the note, sir."

"Did you open it on the way?"

"Yes, sir," said Martin.

"You made a habit of opening my uncle's mail?"

"Yes, sir, unless it was sealed with wax."

"You haven't anything in that desk such as IOU's, or any mementos like that, have you?" asked Ryder of Claussen.

"Not a scrap," said Claussen.

"No notes?" asked Ryder.

"Not a shade of anything," said Claussen.

"There were notes up to sixty-five thousand dollars," said Martin.

"Out the window, perhaps?" suggested Ryder.

Martin shook his head and sniffed the air. "Don't you smell it, sir? Nothing has quite the dry smell of burned paper. Ah, and here are some of the ashes that blew in from the window over the shoulder of Mr. Claussen."

He GOT down on his knees and gathered on a piece of paper some brittle little pieces of ash on the floor. He took them back to Ryder, saying:

"There's part of a watermark on this flake, sir. There's no doubt about it at all. These are paper ashes."

"That desk is a regular pasture, isn't it?" said Ryder. "All sorts of poor devils come in and get fat off it.... What shall we do with this fellow, Martin?"

"Burglary and the possession of a concealed weapon; that sometimes mounts up to a good many years. I'd give him to the police, sir."

"Don't be a venomous fool, Martin," said Claussen. "I can send you up the river for ten years."

"Thank you very kindly, sir," said Martin. "It would be a pleasure to accompany you."

"Can he do what he says?" asked Ryder.

"Sir?"

"Can he send you up the river?"

"I don't doubt that he can, sir. There have been certain unfortunate moments in my past life...."

"Take him down to the street and turn him loose," said Ryder.

"Monsieur, is it not foolish to be honorable with a thief?" asked Martin.

Claussen merely rubbed the little red patch at the side of his chin where the fist of Ryder had landed twice; and he considered first the valet, then the master, in silence.

"That's all," said Ryder. "But by the way, how did you get in?"

"I came in over the roof of the adjoining building."

"That would take nerve, and his knees and elbows would show the climbing," commented Martin.

"How did you get in?" repeated Ryder.

"As I told you."

"Think it over for a moment," suggested Ryder. "Otherwise, I'll turn you over to Martin and see what he can do with you."

Ryder walked a step or two through the room. Then Claussen said: "Well.... I knew that Marene Sutherland had a key to the place. When I left here, I went to her hotel. She wasn't in. When she arrived, I got the key from her."

"Oh?" said Ryder. "Just asked for it, and she turned it over to you?"

"Yes."

"You don't lie well. You really don't," said Ryder. "How did you force her to give you the key?"

"I happen to know a good deal about Marene..." growled Claussen.

"So you frightened her into giving up the key? Well, put it on the desk."

Claussen obeyed.

"Take him away, Martin," said Ryder. "And when you come back, look on the roof under this window and see if anything is lying there."

Martin nodded and went into the hall, where he waited.

Claussen, turning at the door, said over his shoulder: "You've turned out to be an interesting fellow, Ryder. Very!"

He walked down the hall with a good, brisk step, while Martin slunk like a cat behind him.

Afterward, as Ryder started to undress, Martin appeared with a report that nothing had been on the roof beneath the window.

IT was not the first-page account that Ryder dwelt on the next morning. He sat up in bed with his coffee and passed the paper to Martin.

"Read me Jimmy Hickey's column," he directed. "I want to get the sound of it in my ears."

Martin began to read, with his precise enunciation and the faint foreign tang in the "i's" and "w's":

QUOTE

"John James Leggett committed suicide.

"Thirty million dollars was more than he wanted, so he just said: 'To hell with everything.'

"He began to yearn for the good old days in Canada when he was ripping the gold out of the earth; he hankered after the beans and bacon and the bite of the black fly.

"So he gave a beautiful dinner and, being about to die, he asked to it some expensive Young Things.

"He wanted Spiritual Advice, so he asked a race-track gambler, a moving-picture False Front, a columnist who once was young and bright, a political Whiz-bang, and he also asked a young nephew, a little harder than a wolf's tooth and a little sharper, who had nothing to gain by his uncle's death except thirty million dollars.

"In the course of the party, he hinted that before the end of the evening he was going to prove to everybody that one of his guests was a cross between a skunk and a laughing hyena. But the end of the evening never came. J.J. Leggett lay dead in his office with a powder mark on his forehead and a bullet right through his brain.

"The police say it was suicide. But if J.J. Leggett had any reason for dying, you and I ought to have been dead long, long ago; we never should have started living.

"Anyway, that's all we're going to know until the will is published. And then won't it be nice if he has left big, fat legacies to all of his chief mourners? By the way, why was Porter Brant hugging to his breast all evening a certain long air-mail envelope?"

"So," said Martin, "it ends. This Jimmy Hickey is not a big knife but a very sharp one. He leaves no meat on the bone, sir."

"There's a lot in what Hickey has to say," decided Ryder. "Isn't it true that every person at that party might have had a reason for murdering my uncle?"

Martin was silent.

"At the present time," said Ryder, "you don't want to give me anything; not even good advice. Because when I first arrived and found my uncle treating you like a member of the family, I said a few pretty sharp words. But, after all, you have a brain that I could use and I have a brain that you could use; besides, we have a common purpose, which is to find out who shot J.J. Leggett. Why shouldn't we get together?"

"Certainly, sir," said Martin, but a shadow of reservation appeared and vanished from his eyes.

"Go back to my last question. Do you think of a single person last night who has perfectly clean hands?"

"There is Eileen Durante," said Martin.

"Unless she's too perfect to be true," suggested Ryder.

Martin accepted this remark with a nod. He added: "I know that all the men and some of the women, at least, have had money from Mr. Leggett. And money is the same as blood when it comes to paying back."

"One person didn't do this, Martin."

"No, sir."

"I'm glad you agree. How do you see it done?"

"One takes the attention of Mr. Leggett and holds it. A second one puts a gun to his head and shoots him down, sir," said Martin.

"That means there were two of them in the study with him at the time of his death," said Ryder. "Now notice this: At the moment, people were scattered all through the place. They were going here and there, but not one of the lot noticed anyone at any time entering the study. Doesn't that seem strange? Nobody has the slightest scrap of information to offer."

"Naturally I noticed that, sir."

"Go a step farther with me. Those people formed a coterie. They all had been asked to this place many times."

"Except Miss Durante, sir. Mr. Ravenna brought her specially last night at Mr. Leggett's request. Mr. Leggett seemed to think that there should be one really good girl present... after he knew that you were coming."

"Ravenna and Eileen Durante. We could leave them out of the picture, I think.... And Miss Leslie Carton," said Ryder, lighting a cigarette, "has a damaged reputation along with the rest of those girls?"

The silence endured for a moment. Ryder looked up sharply.

When Martin felt his eye, he said: "I don't think you want that question answered, sir."

"No," answered Ryder, breathing out a great cloud of smoke. "I don't want it answered." He took a turn through the room. "The fact remains that all of those people know one another well. They make a group by themselves. You follow me, Martin?"

"They might have planned the murder beforehand?" asked Martin. "They all co-operated, you mean, sir?"

"I mean that," said Ryder, "and I mean that if we can follow the trail of any one of them to the finish we'll probably find the whole crowd. Any clue we can trace probably will be a gun held at the heads of all of 'em."

Martin did not answer, but he stood a little straighter and taller, like one about to take a step.

"Do you know any good private detective agencies?" asked Ryder.

"There is one which a friend of mine runs, sir."

"Telephone for him, and ask him to come here. But not at once."

"No, sir?" asked Martin.

"No. Wait a moment."

After a moment he said: "Martin, give me the telephone number of Miss Carton."

Martin picked up the pad near the bedside telephone and poised a pencil over it.

"Before you go any farther, sir," he said, "perhaps you ought to remember that the police have closed this case. They are satisfied that it is suicide."

"The man who talked to me yesterday never could have committed suicide," said Ryder. He dropped a hand into his coat pocket and gripped the golden angel. "Even with every proof against us, you know and I know that it was murder. Am I right?"

"Yes, sir. You are right," said Martin, and wrote down a number on the pad.

A moment later Ryder was saying over the wire: "Did I wake you up?"

"No, I keep country hours in the morning," answered Leslie Carton.

"I want to see you if I may."

"Of course you may. I'm about to take a turn around the reservoir in the Park. Will you come along? The entrance south of the Metropolitan Museum...."

"I'll be there in ten minutes," said Ryder, and sprang out of his bed.

"Get your detective up here in a couple of hours, if you can," he directed Martin; and a moment later he was amazed to find himself singing in the shower.

WHEN the taxi brought him to the Park entrance she already was walking up and down in a thin, rust-colored suit with a pale blue mist of chiffon about her throat. The glory of the morning drew suddenly close to Ryder and the automobiles which whirred up and down the avenue sang like violins for him. The shoes she stepped in, the very feather in her hat shared her life. He felt that he had spent all his years in the cold of a dark winter.

"Which way shall we go?" she asked, when he shook hands.

"Any direction away from unhappiness," said Ryder. "There it goes—over my left shoulder."

"I throw mine away, too," she said. "Whatever is horrible and sad we won't talk about."

"Do you mean the thought of my Uncle John?" he asked. "I don't mind his ghost walking along with me."

"He meant such a lot to you?"

"He did."

"Do you carry your whole life along with you like that?" she asked. "Does it all walk up and down with you?"

"I carry a lot of it along. You know how it is? Poverty gives us sharp teeth and we bite pretty far into good moments."

"You've something serious in your mind. Will you talk about it?"

"I want to know what had given you the jitters when I met you on the stairs. What had happened to you?"

He told himself that her color did not change and certainly that smile which had been for the beauty of the morning continued.

She walked on for a moment, before she said: "There was something that I wanted to ask your uncle about. It was terribly important and so after dinner when the people were scattered I went back down the hall toward the studio, When I was nearly there, I heard a dull sound; the sort of a sound that would be made by slamming shut a big ledger—all the air inside the pages squeezing out with one puff. Then I realized that the studio was carefully soundproofed and that no matter how a book was slammed the noise would not be heard so far. Perhaps a gunshot would. I ran up to the floor above and into a room which I remembered overlooked the court. From the window of it I saw the studio. A man was lying on the floor. I saw his body up to the shoulders. And another man leaning over him. I couldn't see the head of either one."

"A man on the floor. Another man leaning over him," echoed Ryder.

"It made me sick with fear. I hurried back. Then I met you on the stairs. I was afraid that if I told what I had seen..."

"You were afraid that you'd be involved?"

"I knew it was too late to do anything about it. I knew the man on the floor was dead!"

"How did you know that?"

"I can't tell. Something about the way the feet pointed out—but I seemed to know. I got down from the window and wanted to scream. But I changed my mind. I felt that in that house it was best to be dumb and blind; to know nothing."

He let the words drift through his mind. Then he asked: "Can you tell me what the question was that you wanted to ask Leggett?" He saw by her smile that she was enduring a sick misery.

"No. I don't think I can talk about that."

"Very well," said Ryder. "We won't."

"I'm sorry."

"We'll drop that, but how could you keep from telling the world that there was something in the study—a dead man, perhaps?"

"I didn't dare to connect myself with such a thing. If I had to be a witness in a court... everything might have been ruined that I..."

"What are you talking about?" cried Ryder.

"I don't know... I didn't mean..."

He saw that she could not go on and his face turned cold with sweat.

"Forget that for a moment," he said, "but tell me why you should have been with people like that crowd of last night. You don't belong among.them, do you?"

"I don't know," she said.

He asked sharply: "You remember that golden angel, that dinner favor you had last night?"

"Yes."

"Happen to have it in that purse?"

"No. Do you want it?"

"It's not important."