RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

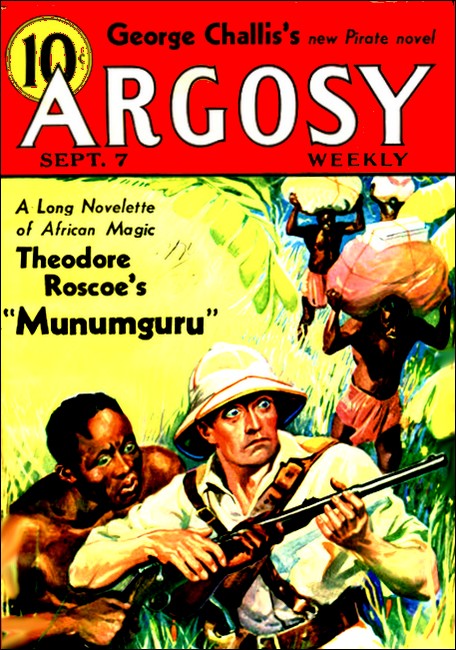

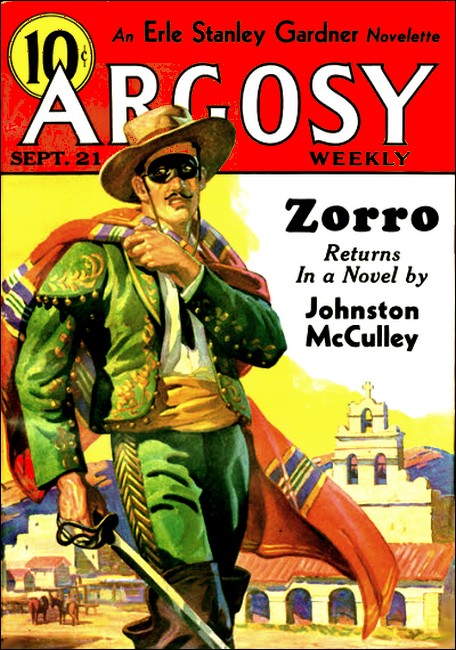

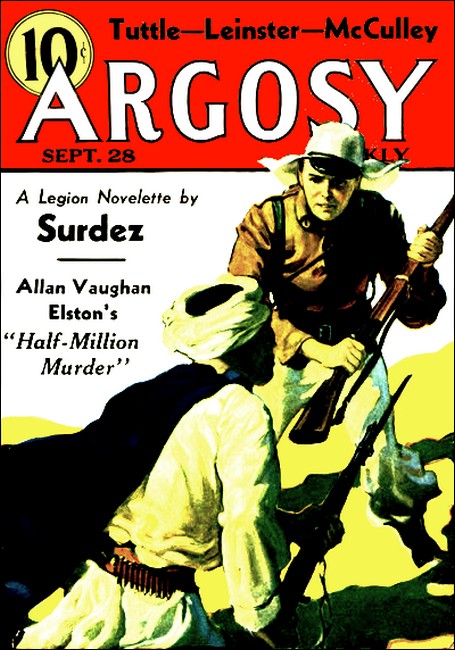

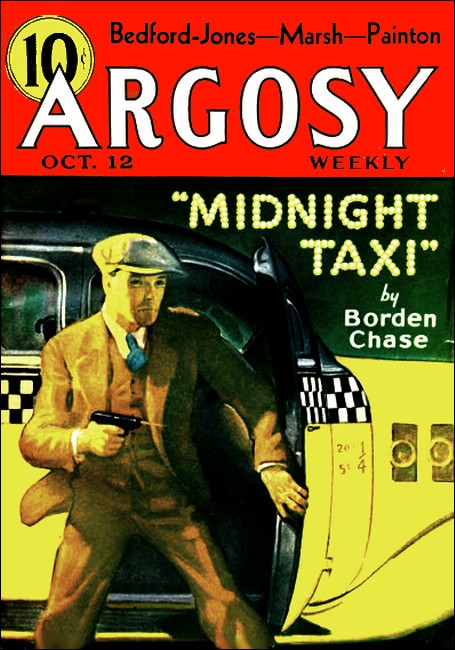

Argosy Weekly, 7 September 1935, with first part of "The Dew of Heaven"

Blood ran as freely as gold on the Spanish Main in the days of Tranquillo the pirate.

It was murder, not battle.

THE setting moon dipped its chin in gold and puffed its cheeks. It was not the golden stain on the moon but the green along the horizon that told Ivor Kildare the sun was about to rise over the Caribbean Sea. The wind was almost dead and the boat felt no waves at all, though the eye could see bright and dark lines running over the water.

Kildare, looking aft into the south-west, studied the triangular sail which had been looming there for some time; and now, as the light of dawn girdled the sea more brightly, he could make out the topsails of a large ship.

Her lofty masts still could catch a breeze, but the low triangle of canvas on the smaller boat behind could reach little higher than Kildare's own small craft. That meant oars.

And every ship, great or small, meant danger. It might be that Henry Morgan had sent out a swift periagua loaded with picked men to try to overhaul the fugitives, and perhaps the tall ship behind was another craft loaded with buccaneers, still drunk after the sacking of the city.

He turned to the Indian who stood by the mast, erect, silent, watching the same sail which troubled Kildare. The moonlight gilded his naked body from hips to head and repainted the shadows to make his strength seem greater. Kildare looked down at his left hand, bandaged but still frightfully hurt by the sword blade which he had grasped in the naked fingers not many days before.

His own broken sword, no longer than a dagger blade now, remained driven into the bow of the periagua, where the hilt of it stood up against the lighted sea to make a dark little cross.

"Luck, or bad luck, Luis," said Kildare to the tall Mosquito Indian who had followed him with such a perfect devotion through so many dangers.

"My heart tells me nothing, father," said the Indian; and Kildare went on forward. He leaned over the girl who lay fast asleep. As he bent lower, in her sleep she smiled. Her hair in the morning light made a pool of brightness about her face; and a curious pain ran through the heart of Kildare.

She had wakened, but without moving hand or head she kept on smiling while her eyes drifted over his face.

"Is there trouble?" she asked.

"There is a sail behind us, and every sail means trouble."

She stood up. As she peered over the sea through the dazzle of the sunrise, her hands were busy arranging her hair, and all he could watch was the slender fingers and the movements of the wrists. He felt like a low-born thief that has stolen the emperor's favorite hawk, or has slipped away with the noblest horse in a king's wide pastures. She, like a poor, mute, senseless thing, accepted him as though he were himself the king.

"They are gaining on us, Ivor," she said. "But why should every sail be an enemy?"

"It is likely that the sail either comes from Captain Morgan's fleet or that it is a Spaniard. Henry Morgan will hang me because he knows that I am Ivor Kildare. The Spaniards will hang me because they still thing that I am Captain Tranquillo."

INSTEAD of answering him directly, she said thoughtfully:

"He was a very famous pirate, that Tranquillo."

"He is a very dead pirate now," replied Kildare.

"If they are Spaniards," she said, "they will listen to me because my name is Heredia, and because the uncle of Inez Heredia is that rich and famous Larretta. Why, Ivor, they would be more likely to cherish you for the sake of the greater reward they will get if they turn me over to my uncle. Besides, they might not recognize you as the man who was captured and taken to Porto Bello."

"You have a reasonable way of speaking," said Kildare. "Do you believe all this in your heart?"

She took a breath and shook her head a little, as people do when they wish to get tears from their eyes. The sun came up that moment and drowned the world with brilliance. It seemed to Kildare that every eye within a hundred miles must see her, she was so beautiful. She interlaced her fingers. Her lips stirred a little.

"Prayers won't turn Spaniards into Englishmen," he told her. "Better pray for a wind, Inez; or shall I whistle for one?"

She had to draw her thoughts away from her prayers and from the sight of that triangular sail behind them, which was now turning from blue to white. "Do I love you because you are so brave, or because you are such a wild-headed hawk?" she asked, smiling at him.

"You love me for a cheaper reason than that."

"What is the reason, then?"

"Because I am yours. Inez, Inez, please don't cry. This may be our last hour on earth together. Don't spoil it with tears."

"I won't," she answered. "You ought to know, being so wise, that when a woman's eyes are wet she is often farthest from weeping."

He took her in his arms and kissed her again and again.

"That is the last. That is our farewell," he told her.

"Look, Ivor! There comes the wind, darkening the sea!"

"Only a puff," he answered. "And see that fellow walk up behind us with his sweeps. That's a true periagua made all of one cedar tree—and twenty men, at least, manning it."

The big oars flashed. They could make out the craft clearly now, and see its sharpness at either end. It had the grace of an Indian's workmanship, but already they could see that white men were at the oars, and standing in the stern was a fellow whose hair darkened and brightened in the wind like metal gold.

"Aye," said Kildare. "Morgan's men!"

"God will not give us back to that beast, Ivor!"

"Those are buccaneers; and the buccaneers have gathered from the whole Caribbean to follow Henry Morgan."

"How can you tell that they are buccaneers?"

"Do you see those fellows in the bows with the long muskets? That is the buccaneer way, and even at this distance every one of them could shoot his man through the head. See the dark of their bodies, too. They've made free with sun that would have killed most Europeans. But I tell them by those wide hats and the peaked crowns. If you want more—see that winking of light at the masthead. That's a machete tied there for a flag!"

A NEGRO voice rose in a husky wail that broke and fell and

rose again.

"Aye, buccaneers," said Kildare. "Every man of the lot has been drunk many a time in Tortuga, I'll swear; and they've killed cattle and buccaned the meat in the woods of Hispaniola. They have to have a slave sing for them or they won't enjoy rowing even if there's a treasure at the other end of the cruise."

"Ivor, there is something that can be done!"

"We can open the sky and climb up on a ladder of sunbeams. There's no other way. In the meantime, a little fighting. Inez, lie flat in the bottom of the boat—there by the mast!"

He picked up a pair of the muskets which were in the stern and, dropping to his knees, held the guns in view at the length of his arms. Luis, the Indian, already was aiming a gun.

"Holla! Holla!" he called.

"Holla!" came the hail from the periagua. "Tranquillo! Ho, Captain Tranquillo! We are coming on board you!"

Kildare watched the steady springing of the crystal wave at the bow of the periagua. He saw the sun-blackened faces of the rowers who, still at their work, turned and regarded him over their naked, powerful shoulders. He was aware, not for the first time in his life, of his own slenderness; a cat among fighting dogs.

"Come, my friends, and welcome!" called Kildare. "I have guns here and they are ready for you."

The tall man with the blowing golden hair took off his hat and raised it high above his head. Such a figure never had been seen before, surely, in such company. He wore a dove-colored blouse buttoned with gold, a lace collar, and more lace falling gracefully over his wrists, an absurd little blue jacket came hardly halfway to his belt.

"Madame, and Captain Tranquil-lo," he called. "We are in fact your friends—but—backwater and keep your distance, lads."

The sea gurgled from blue to green around the big sweeps as they were thrust at a sharp angle down into the water. The periagua lost its way almost at once. One of the men in the bows spat tobacco juice over the side and growled, "Slap him in the face with a quid of lead and he'll listen with his mind open, Louis."

"It is Louis d'Or!" whispered the girl. She had not stretched herself in the bottom of the boat as he suggested. She was just behind him, standing as straight as any man.

Some men said that Captain Louis d'Or was a renegade noble from the court of Louis XIV. His reputation, however, was as red as that of Henry Morgan or any other throat-cutter of them all. The beauty of his face, the elegance of his clothes and manner, simply made him more horrible to the mind. His buccaneers had trailed their oars and picked up enough guns to blow the little craft of Kildare out of the water; but Louis d'Or remained in the stern of the boat, quite unafraid.

HE called out, "You see, Tranquil-lo, that we must board you. Are you going to die fighting, like a fool, or live a while like a wise man?"

"There is the lady," said Kildare.

"Ah, damn the lady, and damn the talking, too!" bawled a great voice. "Close with him, Louis!"

"If that's the bargain, Tranquillo, I make it gladly," said the Frenchman. "After all, she's not rum that can be poured into twenty cups."

"You have a cross-hilted dagger in your belt," said Kildare. "Swear on it."

"To hell with this fol-de-rol!" yelled a buccaneer. "Let's take the boat." He stood up above the side of the periagua with a machete in his left hand and a pistol in his right. But a companion caught him by the long hair and pulled back his head.

"If we can buy him for a word or two, why should we pay three or four lives? That is Tranquillo, blockhead!"

"A lucky thought of yours," said Louis d'Or, in the meantime. He drew out the dagger. A red stone gleamed like fire in the heel of the pommel. "I swear never to touch the lady; never to allow another man to touch her, Tranquillo—except with permission."

He laughed as he ended his oath and jammed the dagger home in its sheath. "Close in. Lay her alongside; give way on the right. That's enough. I'll board her alone, because something may be broken in a rush!"

The periagua slid alongside and touched the small boat with a singular delicacy. Captain Louis d'Or stepped on board and at once jerked up the tarpaulin on which the girl had been sleeping in the bows. Turning, he scanned the nakedness of the hull.

"It's not in sight," said Louis. "You can tell me where it is, Tranquillo. What have you done with the treasure of the Santa Cruce?"

"I never heard of it," said Kildare.

"You never heard of the great galleon that other Tranquillo captured?"

"Never."

"You knew nothing of the way he gave the gold and silver she carried to his men and only kept for himself a double handful of emeralds and rubies and diamonds?"

"I knew nothing of that."

"You thought he was almost a poor man?"

"Yes."

"Tranquillo the Second, or whoever you are, in the name of God why do you expect me to believe that?"

"The truth ought to be seen, Louis d'Or."

"And you trailed Tranquillo across the Caribbean just for the pleasure of stabbing him when you found him?"

"No, T was the man who ran, and he was the man who followed."

"Ah?" said Louis d'Or. "Swarm aboard, lads. Tie Tranquillo like a goat for the market. Pitch him and the girl into the periagua—and then help me search this boat."

The twenty or more buccaneers had been waiting with glistening eyes, pulling at their mustaches, held perfectly silent by their interest. Now they rose in a brown wave and washed on board the smaller boat.

THEY tied Kildare not with cruel force but securely, like men who knew their business, and then followed orders precisely by throwing him headlong into the stern of the long craft.

He turned his head, in midair, to keep from cracking his skull against a crosspiece, made his body limp, and landed without the least injury. The girl came swiftly, without a cry, and leaned over him. The Indian, writhing against the ropes that held him, could do nothing.

"Nothing," said Kildare. "They didn't even bruise the ninth of my lives."

Several of the buccaneers had remained, uninstructed, in the periagua. One of them stood over the prisoner and the girl, and spoke in the garbled Spanish which served all the Finns and Germans and English and French and Italians and Russians who buccaned meat in Hispaniola and who called themselves—because she was the strong nation on the sea—English. In this tongue he said, "I thought you were a man and a captain, Tranquillo. But you're no bigger than a child. There's no room inside your ribs for a heart. Girl, don't touch his ropes!"

He lifted the weight of his hand, but when she took her touch from the arm of Kildare and watched the big fellow, quietly, he let his hand fall again.

The human tide came pouring back into the periagua.

"Pick up Tranquillo," commanded Louis d'Or.

The big man who guarded the prisoner obeyed by gripping Kildare by the hair of his head and jerking him to his feet. And then with a start of savage pleasure the brute stared; but no sound had come from Kildare.

Tall Louis d'Or, walking aft, confronted Kildare with, "What did you do with it?"

"That treasure you talk about? I've never touched it."

"You said more than that. You never had heard of it, either."

Kildare watched the sneer in the face of the Frenchman.

"I never heard of it."

"That's the lie of a fool," said Louis d'Or. "Look here!"

He pointed to the side of the periagua. Over a squared bit of surface the cedar had been trimmed flat and rubbed smooth, and into the wood had been cut a number of little rude pictures such as a sailor knows how to make with his knife—a church with a spindling cross above it, a gallows, three conventional trees for a forest, a long rapier, a sloop under sail, and the most ambitious design of all: a forested mountain with the sun rising over its head. But the carving of hands seemed to be the chief pleasure of the artist. A dozen or more of them were clearly drawn. Between the scattered figures, words which had no connection with one another were worked into the wood with the edge of the knife. On the whole it was rather delicate work.

"This was the favorite boat of Captain Tranquillo the First," said Louis d'Or. "But you know that as well as I know it. And when he sat here at the tiller he filled up some of the hot hours at sea whittling away at this damned, silly cipher. It's a message. About what? About his treasure— which you trailed till you found Tranquillo the Second. Except that he had treasure to write about, why would he have put this work into a bit of wood no bigger than my two hands?"

"He may have had enough jewels to break the back of a Spanish mule," said Kildare. "But about that I know nothing. I give you my word—"

"You will give me plenty of words before I'm done with you. Fetch him to the mast, my lads!" said Louis d'Or. "No, wait for a moment. Read off what's written here, and that may buy you a chance for a little more quiet, Tranquillo."

"I can read the words," said Kildare, "but I can't put a meaning into them unless I have a chance to study them."

"Study 'em at the masthead!" said one of the crew.

They dragged Kildare forward. He gave one look to the girl and saw that she had sunk to the bottom of the periagua and stared hopelessly down.

"Rig a tackle at the masthead," commanded Louis d'Or. "Briskly, now."

ONE of the buccaneers ran up the mast like a monkey with a tarry rope end gripped in his teeth. In a moment he was down again with the rope passed through the block above.

"Free his legs so he can dance," said Louis d'Or. "Tie his hands behind his back and fasten the line to them.—Now, Tranquillo, you see how you stand. The line's taut, A word from me and up you go into the air. You know what will happen then. Your muscles and tendons will hold for a while, but in a bit they'll give way. Your shoulders will break from in back. You'll never lift hand again while you live."

"I know those things," said Kildare.

He looked up, not in hope but because it was necessary to take a deep breath.

"So I ask you again," said Louis d'Or. "What do you know of the treasure of Tranquillo?"

"I've been through the hands of Henry Morgan," said Kildare. "Isn't that the sieve to catch big jewels or small ones? If I'd carried anything away, it would be in the small boat, there, and you've found nothing. Or if I knew anything, Louis d'Or, what a fool I would be to pay with my life— aye, or with the use of my arms—for the sake of keeping a few handfuls of treasure!"

"You talk well enough, but you talk about the wrong things," said Louis d'Or. "Up with him, lads!"

The Indian made a vain effort to break from his ropes and help Kildare.

Louis d'Or had stepped back and was raising his hand when such a cry came from Inez Heredia that even through the sweating flesh of those half-naked brutes ran a shudder. She was calling out: "I am finding it! I am finding the key to the cipher."

"She's only talking to waste our time," said one buccaneer. "How could a woman do in a minute what twenty men haven't done in twenty days? Shall we hoist away, Louis? Let's hear this Tranquillo screech a bit!"

"There is plenty of time for everything," said Louis d'Or. "Hold him here."

He went aft and sat on a crosspiece while the girl crouched and pointed out her discovery, only saying first, "If I can show you something in this, Louis d'Or, is it worth anything to Ivor Kildare?"

"Is that his name?" asked the Frenchman.

"It is. And if he had had the treasure, would he have carried me away in an empty boat? Louis d'Or—"

"Talk about the cipher of these carvings," said the Frenchman. "And if you can tell us enough, I'll see that your Kildare-Tranquillo, or whatever he is, lives until we touch the shore."

She looked desperately up at Louis d'Or, and then brushed a hand across her eyes as though she were casting from her the sudden panic of hope.

She pointed again to the inscription on the wood.

And with bent backs, out of which the muscles stood like arms and big fingers—for every man except the fine captain was naked to the waist—the buccaneers stared and listened. Only three had remained at the mast with the prisoner.

"I've heard it said that wherever there's a puzzle like this, the only way to solve it is to notice repetitions," said the girl. "If letters are spelled here, we ought to be able to make out some of them by the repetitions. But there aren't many repetitions except in the hands. Do you see? There are many hands; some of them have one finger extending, and some have two, or three, or four, or five."

"For the five vowels!" exclaimed Louis d'Or. "But still there's no sense to be made out of it. What words are meant by the mountain, the ship, the skull and crossbones?"

"I don't know. It may all be a hard thing to work out. And half of it may be used to confuse the reader. But you notice that every word begins with a capital? Suppose we use only the capitals, and the hands are the vowels—do you see?"

"There's something in that," said Louis d'Or. "What else?"

"I don't know. I'm trying to see, and in a little more time—for the sake of the kind God, Monsieur Louis d'Or»—"

"For the sake of our hides!" shouted a voice. "D'you see what's blown up into the sky right over us?"

THEY looked as the long brown arm pointed. It seemed to Kildare that the thing was a bit of magic—and white magic it seemed in his eyes. For that ship which had been a blue ghost in the distance, at dawn, had grown upon the buccaneers during all of the time they searched the small boat and then examined the mind of their prisoner and listened to the explanations of the girl.

A huge galleon, it had lifted its courses above the sea, and then all its hull. The wind over its starboard quarter, leaning with the good breeze, and every sail bagful of air, it came rushing with its white bow waves running out on either side. It was near enough for the men to be marked aloft, and for the eye to follow the glimmering rounds of the muzzles of the cannon. Those rounded bows, that hull towering up fore and aft, to Kildare was swelled and loaded with a great cargo of hope.

"Up sail! Get out the sweeps!" shouted Louis d'Or. "My God, have I shipped with a crew of blind men? It's the Inquisition running at you, fools! Jump to it!"

For the great banner that shone billowing from its staff at the poop of the galleon was the flag of Spain. And Spanish justice for buccaneers was as neat as the way of a cat with a mouse: not a sudden death, but a very sure one.

Kildare, jerked out of the way, was thrust aside; there was a creaking of ropes, a rattling of the heavy handles of the sweeps against the tholes. And then he heard the voice of Louis d'Or again:

"Get the girl into the small boat and cast it off. She's enough to stop them for a minute."

It was done.

"Let him come with me!" she cried. "Captain Louis d'Or—"

The long oars ruthlessly pushed the little boat away, heeling it over with their pressure. Then the wind put its heavy shoulder into the sail of the periagua, the sweeps gave it headway, they began to run, gathering speed in impulses like the conscious efforts of a good horse, while the small boat fell astern, paying off till its broadside was turned to the wind.

Inez stood at the prow, waving, smiling. She would not have him remember her with a weeping face.

Above the shouting of the buccaneers he could hear her calling his name, a music that grew smaller than a ghost on the wind. Her features blurred. Still he could see the flash of her waving hand and then the brightness of her hair turning dim until at last she was a shadow.

He had not spoken. He could not have uttered a word. The taste of death had been in his mouth a little before, and now sorrow was more bitter than salt in his throat.

THE Spaniard had grown still higher in the sky, but now he backed his mainsail suddenly. He would, after all, pause a moment to pick up Inez Heredia from the boat. A shout of joy came ringing from the throats of the buccaneers. They were standing with mighty effort as they gave their weight to the big sweeps.

"Set Tranquillo's hands free. Let him come aft!" called Louis d'Or.

So Kildare found himself at the side of the Frenchman, who, like a good sailor, was watching the leech of his sail, not the looming enemy behind.

"If they take us, they take you with us, and all the squalling of the girl will never keep your neck out of a noose. We only have to name you Tranquillo. Then the hanging they failed to give you at Porto Bello they'll furnish you with now."

"That's all as true as a book." agreed Kildare.

"Then lend me your brains," said Louis d'Or. "If you can think of anything that will put more wind in the sail or grease the bottom of this boat for us, let me know. Because the wind is growing, Tranquillo, and that Spanish tub with all her top-hamper is bound to blow up to us before long."

Kildare was looking aft. He said, still staring astern:

"They're picking up the boat now. But they've already lost nearly all their way.

"Take a slant into the wind as close as you can bring her and let every man spring on the oars. And when you're in the eye of the wind, crossing the bows of the galleon, down sail and with your sweeps carry straight on against the wind as straight a line as you can rule. The galleon can only follow by tacking—and you have a chance in three of beating her. These fellows of yours have muscles enough to use them for a long while."

"If I cross her bows, as you say," pondered Louis d'Or, "we'll come within good cannon shot."

"Aye, and of course. But Spaniards are not good at the big guns, and the small ones won't reach you."

"If a single shot caroms on the water and cracks the periagua, we're gone."

"True," said Kildare, and was silent, watching.

The darkness suddenly left the face of Louis d'Or. He shouted:

"Do you hear? You're sea-dogs now, but if the Dons catch you, you'll be dog-meat. And in this wind they'll overhaul us if we run before the breeze. We're going to cross her bows and row into the wind. That brings us under her guns. A single shot will lame us to a walk. Is there a voice against it?"

A good, deep roar came from every throat:

"Into the wind, Captain Louis! Into the wind, Louis d'Or, and chance the damned guns!"

So they turned, slowly, on account of the length of the narrow boat. Edging well into the wind, the leech of the sail began to tremble; and Kildare, as he sprang to an oar, saw the mainsail of the galleon filled again. She towered like a white mountain in the sky, and by the size of her bow wave she had almost gathered full way again.

"Now down sail, down with the mast also!" called Kildare.

"D'ye hear?" thundered Louis d'Or. "Down sail and mast! Jump to it, lads!"

They sprang to it for their lives.

By the look of them, one could tell that Louis d'Or was one who could pick and choose when he selected a crew in Tortuga or Jamaica. There was not a small man in the lot; there was not a soul of them without the brawn of a bull. A few of them ran down the sail and took down and stowed the mast, while the other kept on straining at the oars.

But there was a grim loss of way, all this while; and as the freshening wind met the periagua, lean and long as it was, it seemed to blow the boat to a stop. Anxiously, Kildare measured the diminished distance.

THE Spaniard, coming up on a. good slant, and sailing far closer to the wind than his blunt bows would have led a sailor to expect, was bowling along closer and closer. He had come to such a near distance that the uproar of cheering on the crowded decks became like the rushing of a storm wind. And even single voices could be picked out of the tumult.

A white flag of mist appeared at his bows, blew away. There was a sound overhead like the tearing of strong canvas; and then the sea leaped up in a bright flash far beyond the side of the periagua.

A groan came out of the buccaneers, then, as though the cannon ball had struck their life with a heavy wound. Even Kildare, who knew guns with a rare experience, was surprised by the range of that cannon, for the Spaniards as a rule favored many small guns, the English a few great ones. However, this looked like an exception that would ruin the men of Louis d'Or.

He, however, stood up with a fine courage in the stem, steering right into the eye of the wind and shouting encouragement.

"A little way uphill, and then all the rest of the way down. Pull till your backs crack. Lay out straight and stretch yourselves. Well done, Olaf! Hai, Peters, bend your oar, but don't break it!—Aha, my wild bulls, now that you charge all together, let's see what happens!"

Four flags of the deadly white blew now at the bows of the Spaniard; the quadruple roar of the bullets overhead joined with the brief, chattering thunder of the reports, and every man ducked his head saving Ivor Kildare and Louis d'Or.

Three balls plumped into the sea beyond the periagua. One landed so close to the stern that the wave it threw tipped the frail boat a little. It was very excellent shooting.

"There is some damned renegade English dog on board the Spaniard. Or a French dog who's thrown his soul away into the Spanish hands. No Spaniard ever shot so near a mark. Give way, my lads!" shouted Louis d'Or. "Now, Tranquillo! What do you say to my jolly fellows?"

"If you couldn't conquer a kingdom with 'em, you could rob the king, at least," answered Kildare.

And there was breath enough left in two or three throats to laugh a little.

The only black man of the lot, a creature who looked like an ape, with a forward thrusting head on a vast neck that was overgrown with hair almost to the shoulders, now pitched his head to the side and burst into a rousing song, with a wail and a yell to it that maintained a strong rhythm. Kildare could not understand the obscurely pronounced words, but he saw that a new life came into the crew. They bent to their oars with a longer sweep.

They jumped to that rhythm until the periagua leaped more and more quickly ahead.

And now they had come, certainly, to the critical moment. Those great bow guns of the galleon must be close to perfect range, and the periagua, if it remained unscathed for a few more minutes, was certain to draw away to safety.

Once more the smoke puffed from the bows. Something rushed like a viewless devil past the ear of Kildare. A wind pulled like invisible hands at his flesh. And right alongside a shot plumped into the water and hurled a column of sea into the air and on board them, blown by the wind. Two other shots had fallen short as Louis d'Or shouted:

"Overboard with him! The best part of him is left, but we can't use it!"

Kildare turned and saw a headless body lifted and flung into the water.

IT did not sink at once, but lay in the midst of a spreading stain of red. Then a curving spin rose above the surface, furrowed the water.

He could see the long, pale belly of the shark—and the dead body disappeared.

Even Louis d'Or was silenced by a thought for a moment after this. From the Spanish ship a great voice of disappointment came howling across the water as though pouring from a single throat.

Immediately another four-gun volley was fired, but all of these shots fell well astern.

It was plain then that the Spaniard, in his eagerness, had made a great mistake in sailing. He had brought his ship too near to the wind, and now the fore-topsail was taken aback, spatting the mast with a noise as loud as a hand-clap close to the ears. The galleon shuddered visible and then paid off. It was a vital distance that had been lost.

"Easier now, my lads!" called Louis d'Or. "Easier, easier! We've sailed through the mouth of the tiger and only been scratched by one of his teeth. But if this damned wind keeps freshening we'll have the Spaniard up with us again. Steady, and a long stroke should tell the story for us."

Half the strain was taken from the heaving bodies of the oarsmen, but still the sweeps worked with what seemed hardly less power than before.

The Spaniard, if he had been put out of cannon range for the moment, was not entirely disheartened. He began tacking into the wind, sailing on courses that swept him back and forth. As a heron beats up into the sky with the strokes of his hollow wings cupping the air while the falcon swims swiftly around the horizon and so mounts, in the same manner the long boat was urged by the oars against a windy river of the sea while the ranging galleon swung back and forth and at every tack came closer to its target; for the rowers were beginning to feel exhaustion.

Their heads dropped to this side or to that and there remained. Their mouths pulled at the corners so that they seemed to be grinning. The cords of their necks thrust out. Their bodies were all in a tremble.

Louts d'Or pulled his long rapier twice half out of the scabbard as he looked at the galleon over his shoulder. Then he stared at Kildare and asked:

"Well, you had one bit of good advice in your head; have you any other?"

"Yes," said Kildare. "To rest on our oars and breathe ourselves, then run back at them and fight."

He had hardly said this when the wind blew a good, hearty gust that tipped every wave with white; then the breeze died down suddenly, the waves fell into a welter of unquietness, merely, and when they looked back they saw the sails of the galleon hanging loosely down like the cheeks of an old man.

The heads of the rowers dropped forward; slowly they oared away, and every stroke took them that exact distance from the galleon until the hull of it dropped into the sea again, and then the courses sank into the blue, and the blue itself ran up, like a dye soaked from the sea, until all the upper sails were stained also.

THEY lay—literally —on their oars, with their heads fallen forward and tipped up and down as the waves swayed irregularly the long blades of the sweeps. They could thank the lightness of the cedar boat for letting them escape from the wind and the Spaniard by force of their muscles only.

Louis d'Or said, "Brothers of the coast!" and every head was jerked up suddenly.

"Here," said Louis d'Or, who remained standing in the stern as he had all through the crisis of the chase, looking bigger and more master of himself and the crew than ever before, "here is this Tranquillo the Second, who chased the first Tranquillo and killed him in a fair fight. With enough brains in his head to help us away from the Spaniard, he is still among us. But the treasure of Tranquillo is not with us. Now, brothers, give me your voices. What shall we do with him?"

The shortest man of the crew was the one who answered first. He was an Irishman, the shortest of all the buccaneers, but much the broadest. He had blue eyes and a skin that never would be sun-blackened but burned into freckles that looked like dark blisters. The tip of his nose turned up and was cooked constantly red and raw by the sun. He spent a good deal of his time touching the raw tip with a tentative forefinger, and then looking at his finger to see if it had brought any of the singed skin away.

His name was Padraic, so he was called Pat. He spoke up in a voice curiously high and whining, like a dog in a cold night whining outside the door of a house:

"I would like to see Tranquillo's sword, first of all. We can talk after we've seen his sword."

"Why do you want to see his sword?" asked Louis d'Or.

"Well," said Pat, "I knew a Portuguese that had been in Kingston, and the Portuguese knew a Finn that had sailed with Tranquillo the First and Tranquillo the Second. He said that this English-Italian had a sword no bigger than a needle, but he had a way with it of making a dazzle in the eyes of a man, and then stabbing him through the brain or heart.

"You would have said that a wasp had stung the man, or a hornet. Three drops of blood, and the man was dead. He said—the Finn did—that a good ax, or a machete, or a broadsword with an armored man swinging it, or even a rapier in the hands of a dancing, prancing fencing man like Louis d'Or was no damned good against that needle in the hands of Tranquillo the Second. That's why I want to see the sword."

Louis d'Or looked curiously at Kildare.

"Draw your sword," he said.

Kildare drew it out of the sheath and made a fencer's salute to the three points of the compass. Then he held the sword straight up before him. It was a mere shred, a spindling shard of steel. It was hard to imagine it drawn out to its proper length, and terminating with a needle-like point.

"I'd as soon fight with a moonbeam in my fist!" said the Irishman, staring. "Man, how did you come to fight by such a bit of a thing as that even before it was broken short?"

Kildare said, "I was once in a fight, my arm aching from the weight Of a rapier, and a strong parry shivered the rapier, and left not very much more than half its length and a mere splinter of the steel. But just when I told myself that I was to die, I found that the weight was gone from my arm, my feet were light—and though the sword was gone, there was always the point, the point, the point!"

He raised his voice, laughed, and shot the little blade back into its meager scabbard.

"Now in a good, hard fight," said the Irishman, "when you stand close, and it's sweating and straining, and no room to dance—like a fight on shipboard, we'll say—you mean that that little thing, that needle, is anything against the good whanging weight of a machete that had been ground sharp?"

"Well, my friend," said Kildare, "did you ever fight with a wasp that is always ready to sting?"

THERE had been some murmuring up and down the long periagua during this talk. Now the talk all died away. They remembered that ray of bright steel in the hand of Kildare, and wondered. Perhaps the sting of that wasp would mean the death.

"Talkin' in this way," said the Irishman, "I say, give Tranquillo the riddle to read. If he reads it by dark, let him be one of us. If he can't read it, let him do more good to the belly of a shark than he's doing to any of us!"

The thought seemed good to the rest. With one shout they agreed.

That was how the thing was set. Kildare sat down by the puzzle and pondered over it.

He began where the girl had left off and took her suggestions as though they were inspired. For he had a respect for mind. He himself, without any weight of hand or bigness of body, had managed to hold his own among fighting men. Quick hands and feet had done part of it. Quick wits had done far more.

A man can never be swifter than his brain. And the girl might have done what the gravest man in the world with a library of books would never accomplish.

Kildare, through the heat of the middle day neither ate or drank. He felt neither thirst nor hunger, for his mind drifted strangely between the thought of Inez Heredia and the sense that his own life might end when the sun went down.

He kept going back to the beginning, on her presumption. If the hands were vowels, how would one begin, supposing that only the first letters of the words counted?

"Saqsí—" "Seqsí—" "Soqsí—" It made no difference what vowel he put in the place of the hand, using the first letters of the words, he arrived at no sense.

"Now," said a voice finally, after an age of time, "the sun is getting into the west, Tranquillo." That was Louis d'Or speaking.

There were so many "t's" in the last words that they stuck in the mind of Kildare. Instead of the "S" of "Safe," he read "T."

T-a-q-s-í; that made no sense, either.

But it seemed nearer to something.

Then it came to him that the first letters, the consonants, might not represent their own positions in the alphabet. The letter before "S" was "R" So, substituting in the case of each initial consonant the letter that went before it, he came to "R-A-P-R," which was an unlikely beginning, even if he used any other vowel in the place of the "A."

Instead of taking the letter before, he would try the vowel after. This made: "T-A-R-T-"

THE brain and heart of Kildare leaped. That westering sun was

already golden in the west. Soon it would be red, and then it

would drop like a stone and leave the world to the quick rush of

the tropic darkness, like a flight of black wings. He had to

hurry. But this was like the beginning of a word. "Tart—"

Then came another hand. Call it "A" again. "T-A-R-T-A-G-A-"

As he spelled out the word, "Tartaga," it seemed to him perfect nonsense, and then into his mind jumped a very similar sound: "Tortuga," that island whose humped back looked like a great turtle. Tortuga—that must be right, and he had reached suddenly to the key of the riddle! But there must be more to come. A hand with four fingers means "O," with five fingers, "U," with one finger, "A." Why then, since the vowels were ordered a, e, i, o, u, the fingers were apportioned in number to the place of the vowel in the alphabet.

This was light indeed. Of the sign of the sailing ship he could make nothing. He disregarded it and rushed on to the initial letters and the hands again. So he spelled out at once: "t-h-r-e-e."

He jumped the compass sign and hurried on still farther. The next made: "s-t-e-p-s—"

He could have shouted aloud. "Tortuga—three—steps—" this was sense and there were words, no matter how obscure their meaning.

He went on, always disregarding designs, no matter how complicated.

And the message that he deciphered now read: "Tortuga—three—steps—from—the —black—rock—to—Dutch—John."

The signs, therefore, were nothing. Nothing but terminals to signify the end of a word and betray the searcher into a vain inquiry into some pictorial meaning.

On Tortuga there was something three steps away from the black rock towards the step of Dutch John. That was the meaning.

What was the thing? Why, it was merely the place where that great treasure of jewels was located, of course!

The sun slid down like a man ducking his head beneath a bank.

"I have it," said Kildare, looking up.

There was an ache in the back of his neck, and he rubbed himself there.

It seemed to him that the eyes of Louis d'Or were green with light, like emeralds.

"What have you?" asked the captain.

"Is there one of you that knows Dutch John?" asked Kildare.

"Dutch John that died of the fever on Tortuga?" asked one of the men. "I never knew him. But I've been drunk with him a few times."

"Do you know where he was buried? Near black rocks?"

"I don't know a thing about rocks, but I helped dig the grave where we laid him. It was a queer thing that he was so fat his body begun to stink less than a day after he died."

"There is a black rock near his grave," said Kildare. "This is what the writing of Tranquillo says: 'Tortuga, three steps from the black rock to Dutch John.' And that's where we'll find the treasure buried."

They were tired men, but they began a great yelling. The sun dipped down, suddenly, and the darkness ran without a star over the sea.

Three days later they had beached the periagua on a white lee shore when at the suggestion of Louis d'Or, the blacksmith's anvil was set up and he was put to work forging a new blade for the sword of Kildare; and since he used a bit of fine Toledo steel and was a high master in the art of tempering subtle, strong steel, his work was a masterpiece.

THEY reached Tortuga, humped out of the water like the back of a turtle. Closer in, they entered the narrow waters between that little island and Hispaniola, and here the periagua was run into a cove and beached. Louis was left to guard the boat. It was still half a mile down the beach to the reported grave of Dutch John, and the men marched rapidly. The water rolled and creamed on their right. On the left rose the big, dark cedars and a crowded growth of clammy cherry, dogwood, fustic, lignum-vitae, logwood, gru-gru palms, and always masses of ferns at every interval.

"Why should Dutch John be buried so far from the anchorage?" demanded Louis d'Or.

"Because," said a buccaneer, "the fever he had was the catching kind. We threw dice to see what men would go bury him at a distance, and I was one of the unlucky ones. However, the fever never came out on me.— There," he added, "is the place— somewhere in there. Aye, and here it is!"

He ran forward suddenly and stopped at a point where half a dozen heavy stones were piled one above the other to make a squat little pyramid. "This is the place!" he declared, still pointing down.

And all about him the buccaneers halted, breathless, staring about them for a sign of the black rock which now meant so much. A cloud of mosquitoes poured like a lazy smoke out of the woods and began to settle for blood but not a hand rose to brush them away.

Then the Irishman ran and beat aside a tall growth of ferns, trampling them down. Behind them, glistening with the jungle sweat like the head of a living beast, appeared a black rock that jutted two feet or more above the ground. A low, groaning sound of relief came from the men.

Pat, turning, made three long strides from the rock towards the gravestones of Dutch John. He halted, stamping his feet into the ground.

"Here!" he said. "This would be the place!"

They began to dig, some with their hands, and some with a pair of adzes which made very good hoes, though the carpenter cursed when he saw the delicate edge of the steel being brought down on rocks.

All in a moment a hole was yawning. Suddenly a hand lifted something between thumb and forefinger. It shone in the sun with a yellow glitter.

"Gold! Gold!" shouted the discoverer. "The treasure is here! We have found it!"

"It is here, sure enough!" said a tall German called Johann. "Then, rally to me, my mates!—Keep the captain's third for ourselves! Down with that damned whip-using, murdering Louis d'Or! At them, masters!"

The crowd formed into two quick swirls, Louis d'Or and a narrow cluster of men in the center, with the negro, the Irishman, and three others, and about them more than twice that number. Some thirteen or fourteen to six made up the tale of the odds. Most were armed with machetes, in the play of which they were almost as scientific as any gentleman dancing with his rapier. The German, Johann, carried an axe on the end of a long handle. One fellow was content with his adze.

There was an instant death. One of the mutineers struck his heavy machete down through the left shoulder of the negro as deep as the lungs. The black man should have fallen in an agony. Instead, he fought as a tiger fights, even after a bullet has touched its heart. The other, trying to jerk his weapon free from the flesh, pulled the negro towards him. The black stumbled to his knees, coughing blood.

The machete was knocked out of his hand by the fall, but he pulled a long, curved knife out of his belt and stabbed upwards into the belly of his murderer. Still on his knees, he struck right and left.

A second mutineer went down; a third was deeply wounded in the leg.

The fight was now regular. There were no firearms. They had been left in the boat by the command of the captain. Therefore the battle was hand to hand; Louis d'Or with his long rapier standing like a tower in the war, and four others working in a circle around his back. A dozen mutineers were striving to break through that living guard.

AS for Kildare, the beach was open k and his way was clear. If he had been half a prisoner even after solving the riddle of Tranquillo's message, he was now able to seize on his freedom at once.

In fact, he turned and made a step or two. But the moment that his back was turned, it seemed to him that the clash of the steel and the howling of the fighters redoubled; it blew like a trumpet in his ears, and in a moment he had whirled and drawn that slender sword of his, shouting: "Louis d'Or! Louis d'Or!"

A pair of the mutineers immediately in front of him jumped about to face that attack from the rear. They struck with their machetes at the same time, full at his head. He stepped just outside the sweep of the weapons, as a feather is knocked back by the wind of a hand-stroke. For a subtle instant their hands were down and in that instant he had sprung in. His sword flashed. He was out again. The point of his blade no longer was brilliant as a ray of sunlight. Some small drops ran from it and one of the mutineers dropped his machete, grasped his throat with both hands, and began to gasp and choke.

"Hai, Juan—are you down?" cried his companion. And then: "Here's for you, Tranquillo!—I'll make you tranquil!—I'll give you a long sleep!— Brother Juan, watch me pay your score before you die."

He was letting drive a maze of strokes at Kildare as he shouted, charging in wildly, for the fallen man was his sworn companion after that habit of the buccaneers of choosing a brother who would guard a man's back in a time of danger.

Kildare danced back two steps. The delicate blade of his rapier engaged the furious machete with a touch soft as silk, but which nevertheless turned the mighty strikes awry. Then the sword darted in and out. The eye could hardly tell whether or not it had touched the flesh, but the buccaneer fell dead on his face.

That was how a gap was made in the circle of the assailants, as Kildare sprang in to the side of Louis d'Or. The Frenchman had been wounded by a grazing edge high on his head; the blood reddened half his face and dripped rapidly down over his finery, but he kept laughing like a happy devil as he fought.

He had lost another man; still another was mortally wounded and fought with his body leaning over, his hand clasped to his gashed side. It was murder, not battle. Eight mutineers against five of the captain's side; and one of the five a dying man. And yet there was still a chance that resided in the educated hands of Kildare and Louis d'Or.

The captain shouted: "Brave Tranquillo!—Heart of my heart! By God, I love you, and we'll die together laughing. Do you hear, Gaspar?"

"I hear," sighed the wounded man.

"You are dead anyway. Be a useful man and run in, let them kill you ten times more, but cut the throat of Johann for us."

Gaspar, without a word of response, straightened and uttered a wild yell. The blood burst in a torrent from his wounded side yet he rushed straight at Johann. The long axe struck him down, horribly hurt. He leaped up again and clove the skull of big Johann like a block of soft wood with a hatchet.

KILDARE saw that from the corner of his eye. He had watched two of the mutineers fall back a step, speak to one another, and now they bore straight in on him with a rush. He knew the meaning of that.

One of them might die, but the other was almost sure to flesh his machete in the throat or the body of Kildare; and men did not survive such strokes as the brush knives were capable of giving. They were two more sworn brothers.

One of them was a mere boy of twenty, big as he was. He had fair hair so light that it blew about his head and face as he ran in, shouting. The other either was prematurely bald in front or had shaved himself to look like a Mongol, and wore his remaining hair in two dangling pigtails down his back. He bounded high in the air as he reached at Kildare; the second lad ran in low.

Fencing would not save Kildare then. He flung his narrow-bladed sword like a dart right into the body of the older buccaneer. A side-step snaked him away from the machete of the second. He caught the man by the sword wrist.

It was like laying hold of a piece of wood, grained and knotted with hard tendons. Instantly the youngster had him by the throat and jerked his machete free. It had done work before, and the bright steel of it was filmed over with a shining skin of purple. Body to body, there was no room for Kildare to work but he had pulled from his belt a poniard that matched his rapier—a dripping icicle of steel, a veritable needle. With that he stabbed the mutineer twice under the arm.

Something thudded heavily against his head. It was the machete fallen from a dead hand. The loose, heavy body poured down through the arms of Kildare and lay at his feet. He leaped over it. He of the pigtails lay on his face with a glittering span or so of the sword projecting from the center of his back. Kildare jerked him up by the braided hair and whipped out the weapon. The hilt was slippery with blood, but the blade was all intact.

He turned, and saw that the battle was ended.

The Irishman, covered with blood and brains, had struck the last resisting mutineer through the head and was stepping back, now, panting heavily. And tall Louis d'Or was spotted red from head to foot.

These and Kildare was only three who remained standing out of twenty-one chosen men who had been alive and well ten minutes before.

The whole place was sopping red. The stones of the beach were slippery with blood that was still welling.

Of the captain's group there were three dead; the captain himself hurt in a trifling manner in the head; the Irishman with only a shallow gash on his left arm; and Kildare untouched.

Of the mutineers in that famous and murderous battle, eight men were killed outright, three died of their wounds at once and two were deliberately butchered under the eyes of Kildare by the captain, who ran the long blade of his rapier calmly through their bodies. One of the entire fourteen remained. He was that same fellow who had been hurt in the leg by the negro, and he had received other wounds before he staggered back helplessly and fell at the foot of a tree with blood running out of him fast. But he had worn a small brandy flask at his belt and this was now in his hand.

He lifted it and called out: "To your health, my captain! Dig up the treasure and let me see the shine of the jewels of Tranquillo before I go to sleep."

The captain stalked towards the man with his red sword in his hand but Kildare caught his arm and drew him back.

"The man's dying," he said.

"I've killed two on their feet and two on the ground," said the captain, "and that would make five for my tale."

"Let him be," said Kildare.

"I give him to you—the dog!" said the captain. "Look, Tranquillo! How God favors me I He wipes out the worthless vermin with whom I should have had to share the treasure we are about to uncover, but more than that, He gives me on the same day a blood-brother worth more than a passport into heaven. Give me your hand!—Here, Pat—your hand also. Here are we three with the manifest sign of God on us and a red world under our feet. Shall we be true to one another?"

THEY stood in a closed circle with blood dripping from the slippery hands which were clenched together.

"Would I be fool enough to have another man near me, after this day's work? Captain, you've done with four of them, but two were on the ground. And this dancing man, this Tranquillo —his ugly mug looks beautiful to me with the blood on it! He killed four fighting men with the fight still in them. My eyes have seen it! Are we brothers, Tranquillo?"

"We are," said Kildare, looking deep into the eyes of the Irishman.

"And I am one!" exclaimed Louis d'Or. He recited: "My hand is your hand—"

As he paused the other two repeated the familiar oath: "My hand is your hand—"

Then all three went on together: "... my eye is your eye, my blood is your blood. Amen!"

That oath had sealed many a hard-fighting pair of buccaneers to a single fortune; but it never before had linked three together.

WITH the blood still unwashed from them, they picked up the adzes and began to dig furiously at the hole which already had been opened.

The dying mutineer began to sing new words to an old tune, keeping the time with the sway of his brandy flask.

Louis d'Or, Louis d'Or,

We were twenty men and more,

Louis d'Or.

And we sailed and we sailed

Till the Dew of Heaven failed,

Louis d'Or.

Louis d'Or, Louis d'Or,

We have changed the gold for gore,

Louis d'Or.

Light the candle, ring the bell,

For we'll sing our song in hell,

Louis d'Or.

Here the adze in the hand of the Irishman rang on metal. They shouted, and instantly had out of the pebbles a box of rusted iron. A stroke with an adze sprung it open.

For a moment, so strong and fierce was the expectation, it seemed to Kildare that the box was brimmed with red and green and white lights of priceless gems. And then his brain clearing, he saw that there was only a folded piece of paper.

"This?" shouted the captain, lifting the paper. "Is this what we find? Look, Tranquillo! Look, Pat! There are eighteen men that have died for the sake of sharing—a damned rag of paper!"

He spread out the sheet, and the eyes of Kildare pondered a design far stranger than that which dead Tranquillo had carved on the side of his periagua but patently from the same brain.

The Irishman was tying up his bleeding arm and saying, philosophically, "It's only a bit of paper chase, lads. That damned ghost of Tranquillo will run us around and around the world before we're through with him."

Here the buccaneer beneath the tree burst into a great, mocking laughter that snapped short. He rolled over on his face and began to beat the pebbles with his hands and feet like a child on the floor, helpless with mirth. Then, as though a hand had touched him, he lay suddenly still.

"It has cost us," said Louis d'Or, "eighteen lives and other troubles to find—a piece of paper. Tranquillo, you've had fortune with you when you looked at the design the fool cut on the side of the periagua. Can you do anything with this?"

Kildare sat down on the beach, cross-legged, and peered at the document. The others stared over his shoulders. The blood was drying on his body, pulling at the skin as it turned hard. The mosquitoes, singing their small song through the wash of the sea waters, gathered unnoticed about the three.

"A cat, a rat, a dog, a mule, a bee, an owl, a cat again," said Kildare. "Then a bow and arrow, a coronet and a crown, a cannon, a twig of flowers, a sword scratched out, a flower again. What the devil is there to say about that?"

"Repetitions, said the girl," remarked Louis d'Or. "Repetitions are the things to look for in the solving of a cipher.—Ah, there's a brain in that girl, Tranquillo. I don't wonder that you preferred her with empty hands to any of the damned mincing fools that most men meet. Beauty kills brains, as a rule. But God made her face the foreword, the true title page of the whole book of her. She would be worth half the treasure if she were here to work out this riddle for us."

"She minded me," said the Irishman, Padraic, "of a girl I left behind me in the old country—except that Tranquillo's lady has bright hair and mine had black, and Tranquillo's is short and mine is tall, and Tranquillo's is slender and mine would fill a door—"

"Then how did she remind you of your girl in Ireland?" asked the captain.

"How can I tell?" exclaimed Padraic. "But all at once I thought of her. Because there's woman in them both, I suppose."

Kildare said, "Suppose you look at it in another way. There are living things, flowers, weapons, numbers. Four kinds. For what? For vowels? And why not? All the five vowels may not be used. But no, there are signs over letters, and perhaps they stand for the fourth vowel."

"What are the words that are written down?" asked Louis d'Or.

"Ma — no — me — you — rej — he — ya — wake — naya — joy," read Kildare. "That's hard to make sense of, eh?"

"Aye, but most of the things must have meanings," said the captain. "That is, if he wrote down a sentence of any length. Well, as your lady pointed out—five sorts of things would mean the five vowels, eh? Then try the consonants the way you did before, and use only the first ones."

Kildare shook his head. He could feel the struggle ahead of him increasing every moment.

"Let me think!" he begged. "I'll sit here till I've found the answer."

Dimly he could hear the captain and the Irishman conversing and agreeing that it would be a hopeless task to bury so many dead men. They could be left to birds and flies and beasts. So the two collected, calmly, the weapons and the money belts of the dead and went back with heavy arm-loads towards the boat.

Finally, after much working, the deciphered message read, "Panama behind peacocks tail San Francisco."

He stood up, stretched the numbness out of his legs, and walked past the dead men, past the gloomy cedars, to the periagua, where Louis d'Or and the Irishman had succeeded in launching the long boat on a rising tide. Over the side he sprang and laid his solution before them.

"Panama behind peacocks tail San Francisco. What does that mean? Which of you has been in Panama?"

"I," said Louis d'Or.

"What could a peacock in Panama mean?"

"You have the message wrong," said the Irishman. "What would the meaning be in such a thing?"

Kildare looked down at his encrusted hands and began to wash them in the sea water.

"Try again," he said. "What does San Francisco have to do with Panama?"

"THERE'S a church of San Francisco in Panama," said Louis

d'Or. "A Franciscan church, at any rate. Would that answer?"

"Ah," said Kildare. "Of course it answers. In Panama in the Church of St. Francis—there's the start. Well, in the Church of St. Francis in Panama there is a peacock, believe it if you can. And behind the tail of the peacock is the treasure of Tranquillo."

"In the church?" shouted the Irishman. "Why would the fool hide it in a church?"

"Where would a man be less likely to look for treasure than in one of the nooks and crannies of a church?" asked Louis d'Or. "The thing's done, my lads! Somewhere in the church of San Francisco in Panama. Somewhere we find a peacock—done in stone, most likely. And behind the peacock's tail is the treasure of that poor Tranquillo! Hai, Tranquillo the Second — why would the fool write down such things? He could remember his secret, couldn't he?"

"Why," said Kildare, "the life of a buccaneer is not much surer than a candle in a blowing wind. And it may be that Tranquillo had a partner in the adventure and that they agreed between them to leave some record of what they had done and where they had lodged the treasure."

"Aye," said Louis d'Or, "and suppose also that Tranquillo with his lot was a hunted man through the streets of Panama—as any but a Spaniard is apt to be chased—he might very well have slipped into the bigness of the church to hide himself."

"And now?" said the Irishman. "Why should we rub our hands and warm ourselves as if we had a fire on a cold night? It's a long cry from here to Panama—and damned hard for a man to get into the town if he has an English look about him."

"The treasure is not ours, but it shall be," answered Louis d'Or. "Shall we go to the anchorage and try to exchange this periagua for a smaller canoa, perhaps?"

"No," said Kildare, "but we can pick up a few extra hands and make the voyage in this boat. She's as quick as a fish in the water. And she'll ride lighter with a smaller crew.—What are you thinking of, Louis d'Or?"

"Of Johann, and how he went down. The dog! I fed him when he was starving."

"He's a fire-eater," said the Irishman, "and where he is now, he'll never starve again."

After that, no one of them ever spoke again of the dead men on the beach.

WHEN they went down the beach, well weighted down by the load of weapons which they were carrying, they were amazed to find that the periagua was gone, and Luis, of course, with it. The Irishman and Louis d'Or began to curse the Mosquito, but Kildare told them, simply:

"If he's gone, it's because he was taken. What's been happening behind this headland we can't tell. Men may have come coasting toward the town and picked up the periagua on the way. It had the look that would take the eye of any Brother of the Coast."

They cached the weapons they did not need and went on up the beach rapidly until, rounding a little peninsula, they came in view of the town of Tortuga, which had been whittled out of the jungle by the labor of buccaneers and their slaves and apprentices.

Kildare, as he saw the place, remembered how, on a day, he had fought the real Tranquillo for the right to use that name; and he gripped his fists so hard that the newly healed wounds in the hollow of his left hand began to burn and ache.

It was as quiet a looking place as one could wish to see. It had not streets, really, but green strips of ground that wandered among the houses, and the houses themselves were little huts carelessly built, for the most part, except where some merchant had put up an ambitious warehouse near the water's edge. Under the trees hammocks were hung; a few wisps of smoke floated softly away over the roofs; an odor of cookery clung in the air. It was the sort of a place that made men relax body and mind.

And yet the work was going forward. Through the palms that shaded the huts here and there Kildare could see the glimpses of the rolling land, and the swaying figures which flashed hoes up and down monotonously, cultivating the acres of maize or of tobacco.

On the beach, newly dragged up from the sea, lay the periagua.

"You see," said Kildare, "that there were a good many hands at work on this business. If Luis had stolen the periagua, he never could have drawn it up onto the shore."

"Shall we take the boat and leave?" asked the Irishman. "Or shall we try to find the thieves and fight 'em?"

He asked with a perfect indifference as to the answer.

"Find them, and fight 'em if we have to," said the Frenchman.

They looked into the periagua and saw that its stock of muskets, ammunition, food, and all the essential supplies of a voyage were still intact. Only Luis was gone.

So the three advanced into Tortuga. They were guided by a growing uproar of voices, loud laughter, shouts; they saw a gathered crowd of such tatterdemalions as it would have been hard to find again in any part of the world.

Some of them were in the bloodstained cotton shirts and drawers of the true buccaneers, recently returned from curing beef and pork in the forests of Hispaniola; others had bought new clothes from the merchants who traded at Tortuga, and every wild color, from crimson to staring yellow was on the backs of the dandies of the Coast.

From a distance, through a gap in the crowd, the three could see what was going forward.

AN Indian was tied to a pole by a rope that bound one wrist.

The other hand and his legs were free, and he had in his hand a

short stick. Ten paces from him a stalwart buccaneer was bending

a bow, drawing the arrows to the head and shooting them with a

practiced hand straight at the Indian.

The fellow helped himself by twisting and dodging in a marvelous manner, but with his stick he struck aside every arrow as it leaped at him.

"That's a Mosquito Indian," said Louis d'Or.

"It's my man!" shouted Kildare, and came up on the run, his friends at his shoulder.

The man with the bow had stopped, wiped his forehead, damned the heat, and called for brandy from his valet— because every self-respecting buccaneer, when he was ashore or hunting pork and beef in the woods of Hispaniola, kept a body servant who was kicked and beaten through a long novitiate until he was hardened to a sufficient brutality and then became a full-fledged master buccaneer. The archer tossed off a dram of French brandy and announced:

"When I was a lad, we used to amuse ourselves shooting at pigeons tied to a string, and if I can't hit a full-sized Indian may I be damned to hell and back. Now for you!"

He took a whole step nearer and began to draw his arrow to the head. The buccaneers shouted in anticipation and leaned forward to watch. Some of them were so newly come from hunting that they had not yet become properly drunk.

They looked like barbarians who had just plundered a civilized town and dressed themselves in the booty. This was the moment when Kildare came up on the run, shouting out that he would put a pistol bullet through the buccaneer if another arrow were fired at Luis.

The Mosquito, crouched in an agony of suspense, tense to make the next parry of the flying shaft, straightened a little.

"Hold your tongue," said the archer. "Are you one of the fools that loves Indians?"

"I don't love them, but I hate to waste them," said Kildare. "And every man here knows that a Mosquito with his spear and irons can keep a hundred head of men in fish on a decent voyage."

"Keep your talk to yourself," said the buccaneer.

"I'd rather split your tongue than hold my own," said Kildare.

The whole crowd started. "Do you hear him, Pierre?" shouted one.

Pierre, wheeling about more slowly, dropped his bow and arrow to the ground.

"Here, boy," he said to his valet, "reach me my sword."

A long, heavy cutlass was instantly put into his grasp.

"Now stand out if you dare and tell me what you are and who you are that comes between a man and his judgment on his own slave!" exclaimed Pierre.

"LET me take this fight," said the Irishman at the ear of

Kildare.

"Let it be my quarrel!" murmured Louis d'Or on the opposite side.

Kildare stepped out into the open circle.

"I am Captain Tranquillo," said Kildare.

Pierre laughed.

"Then I'm Caesar and Hannibal all in one," he said. "Why, you lying fool, Tranquillo would make two of you! He could hold enough brandy to drown you!"

"Wait!" called out a buccaneer. "This is the Englishman who chose to call himself Tranquillo and fought here with the other Tranquillo for the right to the name, and beat him!"

"Then the true Tranquillo was drunk," said Pierre. "Step up to me, liar!"

He made two or three cuts in the air with his cutlass as he spoke, and Kildare unsheathed that delicate sword of his which had drunk so much blood already this day. The sight of it had a wonderful effect on Pierre. He was a man all jowls and no brain, and a bush of whiskers made his head seem to grow directly out of his shoulders. When he saw the narrow sword in the hand of Kildare, he grunted like a pig.

"Are you ready?" he shouted. "Is that damned needle what you hope to fight with? Come to me, Tranquillo, and I'll lay you tranquil for the rest of your life with one stroke."

"You're drunk," said Kildare. "But tell me first what claim you have on this friend of mine, this Luis?"

"He's a Mosquito Indian, isn't he?" demanded Pierre.

"He is that. And what of it?"

"This of it! Was not my own Brother of the Coast murdered last year?"

"I know nothing about that," said Kildare.

"I tell you now. He was murdered. And it was a cursed Mosquito Indian that waited behind a bush and speared him through the throat just as he was taking a drink of brandy in the light of the burning hut."

"Your friend had burned down the Indian's hut?" asked Kildare.

"Yes. Because it was a wet night and we needed heat to dry our clothes.—I say that a Mosquito Indian murdered him, and I swore that I would kill the next Mosquito that I ever met.—Is that justice?"

THERE was a bawling shout from all the true democrats who stood around the place. "Justice! This is a judgment!"

"Very well," said Kildare, "if this is justice, let me fight for my share of it. Are you ready?"

"Ready—and not waiting!" shouted the buccaneer, and charged like a bull.

Kildare, without bothering to parry the tremendous, sweeping blow of the cutlass, side-stepped it and touched the buccaneer just between the eyes; a little trickle of blood was running down the face of the big fellow as he turned, roaring.

"That touch ought to sober you," said Kildare. "Guard yourself!"

The buccaneer, in fact, now came in more cautiously and delivered a sudden attack with great skill and judgment. The blow slithered off the supple blade of Kildare like bright drops of water.

A great shouting began to go up. "A master! A master of the sword! Pierre, you are up against witchcraft!"

Pierre suddenly drew back, uttered a cry of fury, and then flung himself in for a final effort. The rapier of Kildare leaped in and out. Pierre, ending his charge, dropped his cutlass and grasped his sword arm above the wrist. Blood forced its way through his fingers.

"Have I paid the price for Luis?" asked Kildare.

There was another universal shouting.

"Teach me one of your damned dancing tricks," said the defeated buccaneer, "and I'd give up the slaughter of a hundred Mosquitoes. Take the Indian, if you want him, and may he cut your throat for you before you're a day older."

"I take also," said Kildare, "the periagua that you and your friends carried off, and Luis along with it."

"Take what you please," said Pierre, "and be damned while you take it!"

He turned on his heel and strode away; a moment later Luis was free. But he showed not the slightest sign of rejoicing; he merely fixed on Kildare a long, bright, considering look, as though a great thought had just entered his mind.

It was a temptation for them to remain in Tortuga and relax with the good French brandy and enjoy the lazy life; but after they had bought a few supplies, on the same day of their coming they left the island, their crew rounded out by Francois, a strong, husky mulatto they had bought.

It was after they had left that the report came in about the dead men on the beach, and that was the origin of the story which presently traveled as far as the winds blow all over the Caribbean Sea and across the mainland.

The legend told how three men had fought eighteen and left the eighteen dead, while only two of the three were so much as scratched.

It never occurred to a single man that among the dead might lie some of those who had fought with the minority.

THEY had little wind, but enough to give them steerageway day after day, and they used the lazy hours of leisure to elaborate their plans. As for Kildare, he wished merely to be taken to Porto Bello, where, he was sure, Inez Heredia had been carried before him. If she were gone, he first would cross the Isthmus with his two companions and make the wild attempt to find the treasure of Tranquillo. And after that they would help him, as in honor bound, to recover his lady. This compact they made in detail.

The mulatto and the Indian, after they reached the western coast, would be left to guard the periagua after it had been beached and hidden away in some obscure place.

They might not be able to trust Francois farther than they could see him, but the Mosquito Indian was a rock of trust.

Luis, couched in the bows with his pronged spear ready, kept them in more fresh fish than they could eat. He helped to kill time for them, also, by telling them—in the starlight, which was the only time when he would talk —stories about the life of his people.

The last day came, with a good wind at last bowling them forward, and the periagua leaping along like a flying fish, when the Mosquito Indian cried out that he could see the shore.

Actually, the others strained their eyes for another fifteen minutes before they could make out the loom of the land, so wonderfully acute were the eyes of the Indian.

At last they saw opening the mouth of the fine bay of Porto Bello, and the hills that ringed the city around with a fine mist creeping upward, like a smoke from the city.

Here their next adventure was to take place. They became grim and silent as they stared toward the land.

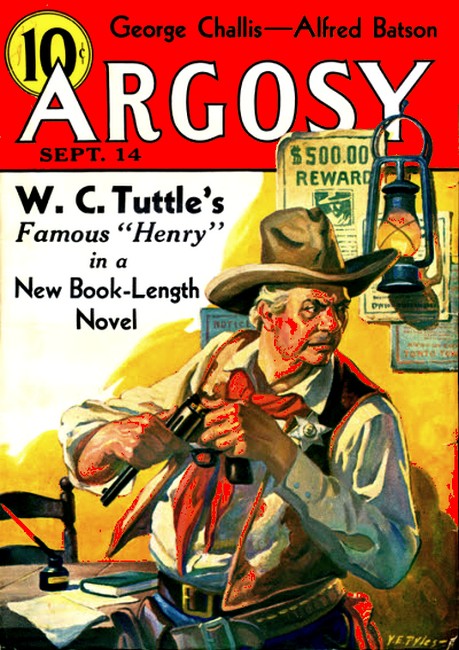

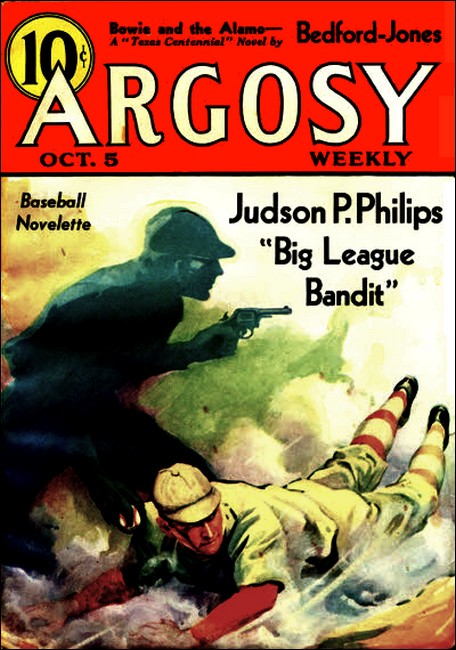

Argosy Weekly, 14 September 1935, with second part of "The Dew of Heaven"

Larranaga help up both hands for mercy.

Ivor Kildare, bold pirate on the Spanish Main, fell into

the snare of his scheming enemies just once too often.

LOUIS D'OR, notorious buccaneer of the Spanish Main, engages his ship in battle with a smaller craft commanded by Ivor Kildare, a young valiant pirate who is sometimes known as Tranquillo II. Louis d'Or captures Ivor and the beautiful Señorita Inez Heredia, who has run away from her domineering Uncle living in Panama. As Ivor is about to be strung up, a Spanish galleon suddenly appears and Inez is put aboard a boat in order to delay the Spaniards who stop to rescue her. Ivor, in order to save his life, manages to translate a cipher carved in wood on the ship which reads: "Tortuga three steps from the black rock to Dutch John,"—directions for buried treasure. Louis and Ivor become friends and they sail on to Tortuga to locate the treasure. Suddenly almost all of their landing party become mutinous. There is much bloodshed, the only survivors being Ivor, Louis and Padraic More.

In digging for the treasure, they find a paper which reveals the next step in their quest: "Panama behind Peacock's Tail San Francisco." After rescuing Luis, a faithful Mosquito Indian, they all sail on toward Porto Bello.

THE sun went down. In the instant darkness which followed, they entered the bay, sliding close to the "Iron Castle" on the western point. Henry Morgan had ruined the fort when he gnawed Porto Bello to the marrow of its bones not long before, and burned the town behind him. But the Spaniards simply moved in hordes of slaves and rebuilt the place.

They had to have a western port for the shipment of the southern treasure to Spain, unless they were to be driven to the long, painful and very dangerous passage south around the Horn.

So Porto Bello had risen, or, rather, it was still rising. When the periagua passed the "Iron Castle" and stood away towards the town, Castle Gloria presented a complete outline. But there were moving lights on the sandbank where Fort Jerónimo stood and the sound of voices giving loud orders, and the noise of hammer on stone and on iron. Plainly, gangs of the slaves were being kept at work by day and by night. Forts Gloria and Jerónimo were now behind.

"We're past the teeth of the danger; we're inside the throat," said Louis d'Or. "Now, Tranquillo, tell us what we are to do next?"

"We can't risk a landing," said Kildare. "That is, of course we can't tie up at a wharf." He raised his head and sniffed the air.

"The tide is out. I can tell that by the stench of the mudflats," he said. "But the tide is at a stand, now, and it will be easy to keep the periagua drifting. With an oar-stroke now and then, you can hold her in place. So sail by the custom house quay and I'll slip ashore there. I'll be back inside an hour, I hope."

"Tranquillo," said the Irishman, "you've been in Porto Bello, they know your face, and wouldn't they rather put knives into you than into a good bit of venison?"

"They would," agreed Kildare, "but they think of me now as one of Henry Morgan's captains in boots and silks and lace and feathers and all that. They won't know the thing they see tonight."

He stripped off his clothes as he spoke, tousled his hair, and stood up naked except for a pair of short trunks. The sun brown of his body was almost as dark as that of an Indian. His hair was fully as shaggy.

And he had an Indian's body, also, slender, rounded and deep in the chest only, with never a bulky weight of muscle but only a swift ripple of strength here and there.

"Ay," said Louis d'Or, laughing, "if I found you like that, I might capture you and sell you for a slave even though you swore that you were my Brother of the Coast.—Go ashore then, Tranquillo. But I must go with you!"

"You will stay here," said Kildare.

"I'll go with you. No man can fight numbers, unless there is a second man to guard his back."