RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old air travel poster (c. 1940)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old air travel poster (c. 1940)

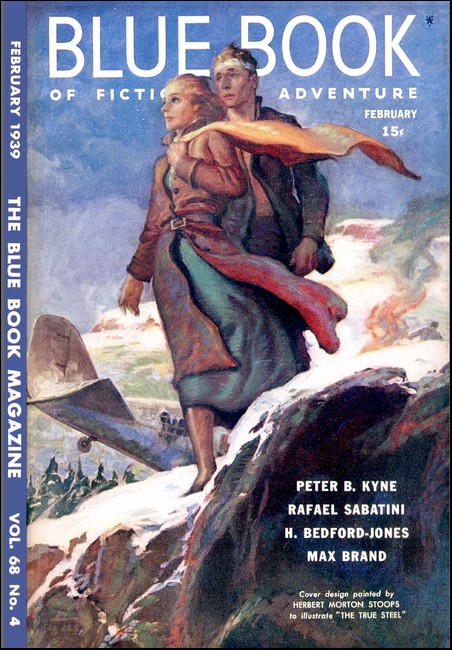

Blue Book, February 1929, with "True Steel"

A murder mystery, and an airplane adventure, by the

famous author of "Last Flight" and "The Flaming Finish."

NOW that she was riding almost literally through heaven, and with the greater part of her future visible across the aisle from her, Katherine Lawrence wondered why she was not more happy. When she turned her head to the left and looked through the window of the plane, there was no fault to find in the sky. It was all that any girl could wish when she was flying toward her wedding day, for the blue-black of the midnight sky was blooming with clouds like a spring field with flowers, an immense field of enormous blossoms which drank up all the brilliance of the moonshine and left the sky to darkness and the stars.

Now and then, when the plane swayed a little, she could see the mountains beneath them, mere heaps and ridges of shadow, casual furrows plowed across the face of the earth. So all the earlier events of her life ought to be diminished by this great moment, she felt, and she tried hard to lift her spirit to the important occasion by casting her mind forward into the events to come, seeing the church in New York, flower-decked, hearing the great church organ thunder and mourn in her honor. But the organ note and the organ vibrancy turned always into the roar of the motors and the frightened trembling of the plane as it carried her toward the new life.

A panic of homesickness overwhelmed her. For consolation she looked across the aisle at her fiancé....

She approved of everything about Davison except his name of Roland. He had proved that he was big enough for football, and there was nothing feminine about the beauty of his face. He had a noble bigness of brow with that single dark stroke of determination marked between the eyes. She had endeavored to tie that name to thoughts of the hero of Roncesvalles, that noble legend filled with the old epic sadness; but she could not help remembering that Roland shortens to Rollie; and suddenly that handsome face was something out of an advertising section, too good to be true. She had to look away hastily to the perfect contrast with wealthy Roland Davison, of Pine Springs, California, and of Long Island.

Contrast was ahead of her in the front seat of the plane: a prisoner who had both hands manacled to the seat—both hands, because he had resisted arrest so desperately and was still dangerous. Since he was on the other side of the aisle, she viewed him at a slight angle and could see the left side of his face. They had bandaged his head, but the cut on his jaw was not worth consideration, apparently. The wound was not exactly bleeding, but it still wept a little, drops of pinkish ichor moving slowly down the face from time to time. Now that he turned his head to look out the opposite window, he showed a blunt profile like a pugilist's. Even without a few days of dark stubble smudged over his face, she felt that she could have picked him for what he was—a murderer.

Half the story of the crime was there in the plane with this James Burke. Pretty Maureen Ervan, for whom he had fired the shot, was now returning to testify in court, after flying West to identify him; and in the seat behind Burke was the detective who had run him down, Michael A. Rylan. Katherine picked up her paper and glanced again through the account of the crime.

IN profile and full face, the grim head of James Burke

illustrated the article together with a surrounding cluster of

smaller photographs of the dead man, Charles Whitley, of his

wealthy father, and of Maureen Ervan looking many degrees more

beautiful than the truth. The details of the shooting six months

ago then followed.

"Jimmy Burke was crazy about me. Too crazy," Maureen Ervan had stated. "When Charley started paying me a little attention, Jimmy went out of his mind. I took him to see Charley. They were old friends, and I thought everything could be talked out. But all at once Jimmy started yelling. He grabbed a gun out of the desk in Charley's library, and he fired it, twice. I fainted, or something. ... I don't remember."

Not love. Of course it was not love that had moved Burke, but mere passion. The pure, high emotion of a Roland Davison never could be felt by that animal nature. She made sure by a glance at Roland, but unfortunately caught him yawning. So, with a frown, she returned to the newspaper account of how Jimmy Burke had fled, disappeared from all ken, and how the Whitley family had offered a reward of five and finally of ten thousand dollars for his arrest. This private detective, this Michael A. Rylan, would become a rich man, comparatively, on account of his cleverness on the trail; but can blood-money do good to anyone?

Katherine turned the page of the paper for the first time. Before she read on, she took a sniff at the gardenias which were pinned at her breast. The manhunt was exciting, and there was a strange, frightful reality about the words, since pursued and pursuer were there in the plane together. Of course the newspaper editor could not resist quoting from some of the love-letters which Burke had written, and which Maureen dutifully had turned over to the law. She glanced at fragments here and there:

When you said good-by the other night, were you just tired, or were you tired of me? You said it as though you meant it; and ever since, I've been going around as though it were the first day of school and all the faces strange to me.

And again:

I wish you hadn't come into the house yesterday, because you're everywhere about it, now.... If I look over my shoulder now suddenly, shall I see a ghost of you disappearing in the mirror?"

Katherine stared at the words. They did not fit the murderer's picture that had filled her mind. Then she read on:

I'm half batty. I look down at my hand, and that was the hand which reached out and touched you and found you were actually there.... I love you... You know how it makes me feel to write that? I haven't fooled around with flirts much. I've never written or said it before.... I love you.... It makes me ashamed to write it, as though I'd said quit in the middle of a fight.... Good-night again. I keep trying to stop writing, but the thought of finishing is like saying good-by to you....

Then came something that made her face hot. She closed the paper suddenly, ashamed, and looked hastily across the aisle toward Roland Davison, and felt vaguely comforted and vaguely disturbed. She took note of the other people in the plane. There were, outside of Maureen Ervan, the detective, and the prisoner, a married couple with an intimate friend who sat slewed around with an arm over the back of the seat so that he could talk to them. He was in his early thirties, but the youth was hammered out of his face and left it lean, hard about the mouth and meager about the chin. He wore the long hair of an artist; he even carried the old-fashioned badge of a flowing Windsor tie. He was a painter or sculptor, not a musician, because now and then his gesture drew some outline in the air.

The married friend looked like a boy stretched to a man's inches. That is to say, he had a large round face and a scrawny length of neck and narrow shoulders. But he was close to forty, while his wife was nearly or quite ten years younger. She was soft and plump and pretty, and wore a rather foolish hat which flared up at one side. To the talk of the artist, she listened with eyes wide enough to drink in every word.

Katherine looked out the window again, and saw that the wind was rising. The clouds, no longer full and compact like huge summer flowers, streaked out into thin wisps like the lines with which a cartoonist gives the speed effects to moving objects. Because they were thinner, there seemed to be less moonlight; in the background the stars still trembled with the tremor of the hurrying plane.

Detective Rylan now asked for food and drink. The stewardess brought him a cocktail, then ham and chicken sandwiches with beer, and the detective wolfed them down. Through a haze of fascinated disgust, Katherine watched. There was something about mere decency of manners, she felt, that distinguished the classes, one from the other. This pride of hers was not a fancy but a strongly controlling force. She was, she thought, set apart from other girls. They smoked, which is unclean for the hands, the lips and the breath; she did not smoke. They drank, which draws a mist over the eyes and across the brain; she did not drink. They enjoyed a petting party; she was untouched. It was not beauty alone that gave Katherine social success, in spite of her haughtiness and her cold manner, she was a good athlete.

The fault of Katherine was the high expectancy which had been instilled in her by her environment and that sense of class which is a fiercer snobbery in democracies than in any other society. She felt that the giving of herself was an event momentous to the world, and therefore she looked even upon rich, handsome, virtuous young Roland Davison with a great doubt. She had to be right, and now she was not sure.

Beyond her window, something was blank that had been legible before, like words blotted out on a page; a certain obscurity was pouring from the northwest, covering the stars even from the lofty altitude of the plane's flight. This troubled her a little. When she turned from the window again, she was surprised to see the stewardess offering a cup of steaming soup to the prisoner. Before he touched it, he stared up at her for an instant, his face savage, his jaw thrusting out a bit; and it seemed to Katherine that the flame-red of his hair bristled above the bandage which girded his head. Then he tasted the drink.

She put down the tray on the opposite seat and let him swallow the soup in two portions.

The creature was not all beast, Katherine observed. The kindness of the stewardess had set him breathing deeply, to judge by the lifting of his chest and the slight flare of his nostrils. He was capable of emotion, as the quotations from his love-letters had indicated before; and as an animal, he possessed a certain magnificence in the bigness of his head and shoulders. The disgust gradually passed from Katherine and left her staring as she might have stared at some lordly specimen of jungle brute behind the bars in a zoo.

The stewardess began to feed the handcuffed man with sandwiches which she had cut into narrow strips—giving him the right amount for each bite he took. Among the lower classes there is a great deal of natural sympathy, Katherine remembered. She could see it in the deftness with which the stewardess from time to time dabbed the lips of Burke, all the while keeping up a smiling conversation which was not too gay to be sympathetic. This stewardess was a small thing, with a saucy, pretty face.

Katherine glanced out of the window again, and was amazed to see that moon and stars together were gone. Outside the glass, a rolling chaos of shadow poured past them; the fish-shaped body of the plane was swimming in a dark sea.

KATHERINE grew sleepy, her head nodding till she lost consciousness. She was roused by the hand of Roland Davison on her arm. He had lost his usual calm and altered to an eager alertness. When he played football, he must have looked like that, half fierce and half afraid, like any fighting man.

"Look!" he was saying. "Look, Kate! Quick!"

She stared out the window. Off to the left and ahead, through the glass she saw a steep form lifting like a high wave towering before a small boat in the open sea. Blowing mist shrouded the face of it so thickly that in an instant it was gone.

"We're still in the mountains!" exclaimed Davison. "We should have been out of them hours ago—a long time ago... Kate, they're having trouble!"

Her brain was still half asleep, but a voice inside her began to say that they could not be having trouble. When a plane has trouble in the air, people are apt to die. There could be no trouble for her and Roland. They were bound for happiness in the bright, narrow oblong of this chamber, as secure as good news sealed into the cartridge that slides down the messenger tube. According to the eternal rule, disaster overtakes only those who have sinned; and what marks were there against her or against Roland?

In that way, dimly, her mind moved through some of the old copybook maxims; then the sleep left her suddenly, and she was wide awake, with the realization that copybook maxims do not control travel in the air and that calm insolence with which man aspires to step across a continent at a single stride.

The stewardess was passing. Davison stopped her with his hand and asked: "Why are we flying so low? Why are we still in the mountains? Is there trouble?"

The plane bucked like an angry mustang and unsteadied the girl, but not her smile as she answered: "We're all right. We have a couple of pilots who know what they're doing."

She went on. Up the aisle the heads which were pressed against the windows turned suddenly toward her. Lips asked soundless questions. She answered cheerfully. Only Burke seemed undisturbed, his head straightforward; but after all, what difference did the nature of the death-cell make to him? An electric current could not kill him with more merciful speed than the crumbling of the ship like chalk against a mountain-side. And to the startled, confused brain of Katherine, it seemed that perhaps the higher justice was striking them all down, blindly, because that one man of evil was among them. She forgot that thought a moment later. Beneath the window a great, ragged maw opened for them with the storm smoking across it.

It seemed to be reaching for the ship before she realized that the teeth in it were the mountain peaks above which they were ascending.

The plane climbed so steeply that her back pressed hard against the seat; and every man and woman in the plane seemed to be shrunk smaller by the same pressure; only Burke sat as high-headed as ever, looking straight before him with unalterable calm.

THE cheek of Katherine was iced by the window against which

she pressed. Now as she looked up, she saw the storm grow faintly

visible in long streamings of shadows among shadows. The light

grew. The flying mist turned milk white, with great nodules of

crystal brightness shining through it; and then they were

launched suddenly into the open sky, as though a door had opened

in a white wall and stepped them out into infinite space. The

moon, lopsided as it grew toward the full, shone almost in the

zenith. Beyond the circle of its own region, the stars shook with

the vibration of the ship; and beneath them stretched the shining

white level of the storm, all in motion like a gigantic river

that filled space from horizon to horizon.

Roland Davison grabbed the corner of the seat and cried at Katherine: "They've got off the beam. They can't find it. They're up here to try to spot a landmark. But all they can see is the clouds.... We'll be getting out of gas.... There'll have to be a forced landing."

His cheeks were pinched in and his eyes had grown big and round. He sat down, still talking, making gestures. She did not hear his words, for all her thoughts had run back home to her father's house like a child out of the cold; and all she could remember was the colored pattern of the rug in the living-room, and the fire working cheerfully among the big logs on the hearth.

Moon and stars went out. The plane skimmed through the white dazzle of the upper surface of the clouds, down into the darker milk beneath, and then again into half-visible darkness.

Detective Rylan leaped to his feet, gripped the back of his seat, slowly lowered himself again.

THE stewardess came down the aisle, speaking to each passenger in turn, leaving each with turned head staring after her. When she came to Katherine, she paused a moment and her eyes grew tender before she said: "Be steady-nothing will happen—everything will be all right; but there will be a forced landing—you must fasten the safety-belt."

"Thank you," said Katherine, and smiled at her automatically.

The girl went on. There was no fear in her. Stewardesses are almost professional heroes, are they not?

Maureen Ervan half-risen from her seat, had caught both hands to her face. Ruth Patterson had cried out in terror.

Patterson drew an envelope hastily from his pocket and commenced to write a farewell note, not about family affairs, but about business.

"For Henry P. Thwaite," he scrawled.

What I've been working on while I was away was the rubber for the joints. You know how crazy we've been to find something that would give the toys motion. Springs that wind up are no good. But I mixed some of that white plastic with the rubber. You know the plastic I mean. The stuff I got from the Harlan Laboratories. Mix that with the rubber compound, and you get a material with life to it. I made use of it for the joints of one of the elephants and made the elephant take five or six steps. I made the tiger open his mouth and show his teeth. The stuff works slowly, but it gives the motion, all right. It has a funny smell. Try to kill that.

I guess we're going to crash. So long, old man.

Bert.

And Michael Rylan was scribbling:

Dear Maggie,

They're crashing the ship. They're killing me, Maggie. Just when things looked good. By God, you get the ten thousand out of the Whitley family because I grabbed the man for them. And Bill Lang owes me sixty-five bucks. You make him come through with it. Don't have nothing to do with Sam Wilson, or I'll haunt you.

Your loving husband,

Mike.

The stewardess was fastening Mrs. Patterson into her seat with the safety-belt, while the poor woman sobbed into her hands.

Roland Davison wrote:

Last will and testament.

Being in my right mind and about to die, I will and bequeath all my property to Thomas Franklin Davison, my uncle.

(Signed) Roland Davison.

Immediately beneath he wrote:

Dear Uncle Tom,

Sell the Unity bonds. They're no good. Buy Caswell, Jones. Look out for Chippinwell. I think he'll crash soon. And see that an investigation of this tine is made, no matter what lobbying it costs you. Incompetent pilot, I think.

Rollie.

Katherine herself was trying to write, but the words would not come, for between her mind and the paper the picture of Burke kept springing up, Burke at the moment of the crash with his two hands pinioned to the seat helpless.

She crumpled the paper she was writing on, and dropped it to the floor. Then she went forward. The ship, heeling sharply as the pilot banked to the right, made her clutch the side of a seat and hold on hard. The upper levels of the storm had broken up and let the moonlight climb down a broken ladder to show the white breast of a mountain just beside them, glistening with ice. She thought they were to crash that instant. Her lips were closed, but a fine electric tingle thrust up through her forehead as though she were screaming.

Then the plane righted.

John Bashfield Rogers, just beside her, had one arm bent around his face to shut out the vision of the mountain which Katherine had seen. Somehow the sight of his weakness gave her strength. She hurried down the aisle to Michael Rylan.

He had his eyes tight shut as he crossed himself and prayed with moving lips. Katherine caught him by the shoulder. She had thought that he was a fat man, but the bulging flesh under his coat was all rubbery muscle.

"Give me the key for the handcuffs!" she cried to him. "You can't let Burke crash like this. Give me the key—for the handcuffs—for the handcuffs."

He opened his eyes. The horror of his dream possessed them. She shouted at him again. Fear had turned his brain numb. Finally he said: "Burke? Damn Burke! Except for him, I wouldn't be here! Let him smash and rot—damn him!"

But he pulled a key out of a vest pocket, and had closed his eyes for prayer again before she snatched it away. The plane heeled once more, staggering her, as she leaned over Burke. She had to clutch at him to steady herself. He was like Rylan, covered with rubber-hard muscle, but steadier than Rylan, as though he were better braced against any shock. Fear had neither dimmed his eyes nor put a glare in them. He looked with a mild curiosity into her face, and then down at the hands which fitted the key into the lock. One cuff sprang open; she unlocked the second and left one of his hands free. There were still two more on the right arm to finish her work.

Then the stewardess was at her, exclaiming sharply, angrily: "Get back to your seat, please! If we land while you're still on your feet, you may hurt somebody besides yourself. Go back to your place, Miss Lawrence."

DESPITE that urgency, Katherine was fitting the key into the

locks of the other handcuffs. She straightened again, flushed and

confused. The deep voice of Burke grunted a meaningless sound.

And there was the stewardess smiling at her and frowning at the

same time. "I'm glad you thought of that," she said. "But hurry,

now! Hurry, hurry!"

Katherine dropped the key into the hand of Rylan and went back to her place. Roland Davison, leaning far back in his seat, bracing himself against a shock with feet and hands, gnawed at his lip while he stared out the window, oblivious of her. As she fastened the safety-belt, she saw Burke turned in his seat and looking back with savage contempt at Michael Rylan. No doubt the detective still prayed with closed eyes. There was such vicious cruelty in Burke's face that she half expected him to throw himself on Rylan with hands and teeth, like a beast.

Then a woman screamed. The sound went up into the brain of Katherine like a white-hot needle and half blinded her.

It was pretty Maureen Ervan who shrieked. The sound seemed to have no ending. It stayed up at high C, stabbing the hearers to the brain-pan. Then Katherine saw a mountain-side bearded with a pine forest. It seemed to lean out toward them, showing above timberline a dim streak of white, clouded over instantly by the dark sweep of the storm. Then they struck.

IN that black welter of wind and flying mist, Katherine had known there was only the thousandth chance of making a safe landing. She was prepared for a great shock, a sound of rending and crashing, and all things in a topsy-turvy confusion. Instead, they merely were at a stop, and hands were pressing the breath out of her with a slow constriction, an irresistible force. That was the safety-belt at work like a python, flattened by its own effort.

She could not breathe, and whatever breath she drew was of darkness. She had not prepared herself for the darkness. If she only had set her mind for that, it would have been easier to endure, and not like a filthy dust choking her lungs.

There was darkness, but not silence. The hoarse, gasping screams of Maureen Ervan persisted. Another sound, full of secure power, was gone from them: the roaring of the motors. In its place was the whistling of the storm; instead of the tremor from the vibrating engines, the plane was cuffed and shaken by the hand-strokes of the wind.

She fumbled at the fastening of the safety-belt. There was a sense that the plane was skidding before the wind and might be blown from the lip of some high precipice at any instant. She hurried, hurting her fingers with her efforts; but she had to readjust her body in the seat before she was free from the belt:

Another screaming voice joined that of Maureen. Suddenly the girl was still, but the other voice went on in pulsations of silence and wild outcry. It was not like the shrill fluting of Maureen. It seemed to come out of a throat unused to making the sound. Once, during a hunt, a horse had gone down horribly wounded by the ragged stones of a wall. The shriek of the poor beast was still in Katherine's ears, and it was like this sound. This was the outcry of a man—of Burke or of Rylan, perhaps? And yet it seemed too far away to be from the inside of the plane. Through the blackness she had a picture of Maureen sitting hushed, forgetting her own terror as she listened to the agony of that other agonized screaming.

A wavering hand of light brushed past her window. She thought for an instant, with wonderful relief, that they were on an aviation field and that the light came from the electric torches of rescuers who were hurrying toward them. Then she remembered the rugged face of the mountain.

The light increased. It flared up high from the head of the plane, so that it showed her through the window the drive of the storm. It looked like nothing she ever had seen before, or as though the world were exploding into fine fragments.

AH this had gone at a quickstep through her mind while she worked free of the safety-belt and out of her seat. Then a voice roared out like the bellow of a bull: "This way! This way out! Look lively!"

She turned down the aisle. Dark figures swarmed there before her. Some one rushing from the rear knocked her aside with almost a greater shock than the landing of the plane. That was Detective Rylan, fighting to get through the compacted group. She saw his distorted face by the increasing flare of light that looked through the windows of the ship. Many voices were crying out. She knew she would be the last, and the flames would have her before she reached the open air. All at once she was beating with both fists, thrusting and struggling with the whole strength of her body.

THEN she was in the clear with the wind blowing the wits out

of her head, wrenching at every garment. The cold closed on her

like a shower of ice-water. She staggered in the gale as though

she were about to blow away on it.

She could see, now, what gave them the light. The whole head of the plane was in flames that spurted out like jets of water; out of one wing ran a huge cascade of fire which the storm whipped away in double handfuls and sent bucketing off toward a fringe of snow-encrusted trees that drew near and suddenly retreated and advanced again as the fire was flung toward them or died away. And off there at the front of the ship one man, a black, jumping ape against the yellow fire, was jerking open the door beside the pilot.

He disappeared inside as a long arm of flame slid up under the belly of the fuselage, as far as the very rudder of the ship. Around Katherine, people staggered in confusion, leaning one shoulder into the wind, shouting out aimless words.

Now from the open door of the pilot's cabin appeared a man who lowered and caught in his arms a limp body. He came away carrying it high against his breast. The head and legs and arms dangled down. There seemed to be ten joints in every limb.

Little points of fire adhered to both these figures. Something apart from her, impersonal in her brain, kept saying that that was heroic. That was the stuff heroes were made of. Then she saw that it was the red-headed criminal, Burke the murderer, who laid the broken figure on the ground. Burke himself lay down and rolled like a dog in the snow. Another figure issued from the open door of the pilot's cabin, walked with uncertain small steps for a little distance, then collapsed in the snow.

Somehow the feet of Katherine Lawrence had brought her to the place, by this time. She found the man lying on his back, his eyes closed, his mouth agape. He drew breath with a snoring sound; then the breath came out with a scream, though he was unconscious. It was his screaming that she had heard.

He was a fat man. One of the yellow moths of flame had lighted in his hair and was burning it away. She clapped a handful of snow over the place. She got hold of him and rolled him over on his face and over again on his back. All the flickering bits of fire had disappeared by that time.

SOME one grabbed her by the arm to drag her away. Davison

cried furiously at her ear: "Come on, Kate! Get away from here!

The plane will blow up in a minute."

"Help me!" she cried to him. "Help me carry him!"

He caught up the head and shoulders of the man. She supported the legs at the knees. The wind stopped them and staggered them with its invisible hands again and again as they bore the poor fellow to the place where Burke had laid his companion.

No one else had thought of tending the injured. Katherine jerked off her jacket and stretched it under their heads. She knew, by a look at them before the plane had started, that the fat fellow was the co-pilot, and the senseless figure beside him was the pilot in command. There was a streak of blood diagonally across his face.

Some one crouched beside her to offer help. That was chubby Mrs. Patterson. When Katherine tried to speak, the wind shoved an icy finger inside her mouth and blew out her cheek like a rubber bag.

A VOICE was shouting louder than the storm. That was Burke,

again. His was the same bull's bellow that had showed the way out

of the ship in the first place.

"Where's the stewardess?" he was roaring. "Where is she? Damn you, have you been standing around and left her inside? Where is she?"

The rolling in the snow had not put out one avid spark of fire in his coat. Now the wind fanned that morsel of flame to strength. It was eating out a round spot, shining at the edge. It seemed to Katherine to be sinking a hole into his flesh.

The wind changed; or else some unusual eddy curving from the hollow forehead of the mountain counteracted for a moment the normal sweep of the gale and blew toward them the smoke and the flames of the burning ship. The oily reek half-choked Katherine. She had to lift her hands to defend her face; but through her fingers she saw Detective Rylan step to Burke and snap a handcuff over one of his wrists.

Then Rylan lay on his face in the snow, and Burke was racing back toward the plane. The flying smoke and snow-dust commingled met him and covered him from sight.

She saw Roland Davison and tall Patterson, that grotesque, run after Burke. But when they reached the level-streaking sheets of smoke, commingled with those red threads of fire, they stopped, recoiled with their backs to the ship and their arms up to cover their heads.

Then she saw Burke come out of the flying smother, making his way with uncertain steps. The stewardess sat up in his arms with her head fallen back on his shoulder. Davison and Patterson took that burden from him; and Rogers the artist was there also, too busy keeping his footing against the wind to be of any use. They were all vague images of men, at this instant. The real one was Burke, now stretched on the snow, hacking and coughing and fighting for breath. He had not even enough wits left to roll in the wet and put out the dozen bits of fire that worked at his clothes. Katherine with handfuls of snow smothered the flame wherever she found it.

He was up on one knee; he was on his feet, reeling; now he was brushing her aside and making for the stewardess. Katherine got to the girl an instant later, and found Burke manipulating her legs and arms. Her eyes opened, and she screamed. Consciousness came back, and she bit off the outcry, setting her teeth over it.

"Right leg's broken below the knee," said Burke. "Left arm's snapped above the elbow. She's in a hell of a mess. Listen, you! What's your name?"

"Is Fatty Wood all right?" she gasped at them. "Is Ken Wood all right? He's the co-pilot. Is he clear? For God's sake, are they both clear?"

"They're clear," said Burke.

He took Katherine by the chin and turned her face toward him.

"The fat fellow belongs to her," he said. "Go fix him up!"

He added to the stewardess: "They're clear. What's your name?"

"I'm Alice Gordon," she said. "Take me close to Fatty Wood—please take me close to him if he's hurt."

They could hear the pulsating cry of the fat co-pilot with the exhalation of every breath.

"He's all right," said Burke, "but you're a mess. Wait till we get you straightened out, and then you can have all of him you want. Here, you, and you tall fellow—give me a hand. We've got to get 'em to cover."

THEY got the injured back among the trees, but the trees were no good. Only half a dozen ranks of them stood along a dangerous down-pitch that seemed to be sheer precipice; and through the scattering of the trunks the wind whistled all the higher octaves. They had at least one freezing night to face, and they had it to face in nothing except the clothes they stood up in. Nothing else had been brought from the plane. That fine silver fish which had been so at home as it swam through the sky was now a fire-gutted, twisted, deformed wreck. And they had not so much as a hatchet to fell saplings for a sufficient wind-break. Instead, they had to use metal fragments torn from the plane to maul and beat the narrowest of the young trees until at last they could be bent over and broken off. A fire was supplied from brush which could be pried or torn up by the roots. Two dead trees gave a treasury of easily inflammable material. The women attended to the fire. Also they bent and beat and twisted off the branches and tufted tops of the saplings which the men managed to bring down. Out of the evergreen boughs they built beds for the injured; and men and women both were at a stagger with weariness before at last a wretched excuse for a windbreak was stretched across the trunks of three trees which stood providentially close.

Katherine Lawrence did her share, wondering the while why they continued the struggle; for the wind blew through her body and laid a lump of ice in her vitals. She wanted to lie down and curl up to cherish some last bit of warmth that must be lingering inwardly, with her life. If she lay down, death would come; but death by freezing, she had read, was a mere falling asleep; this other death was torment exquisitely prolonged, an agony of futile effort. They were like the last relics of humanity foolishly clinging to existence after the sun was blown out. That blowing darkness, that enormity of wind which howled around the mountain, was in fact like the end of the world. The firelight made only a feeble step or two into the hurricane which carried the snow-dust as thick as a London fog, at times. This firelight showed her the three injured people stretched in the growing shelter of the windbreak—the pilot, David Hardy, with open eyes and utterly still, while Ken Wood the copilot no longer cried out, but groaned with every indrawn breath. By the same light she saw the others of the party reeling into the storm, head down, or hurried before it with gigantic steps. Their faces showed her own bewilderment and despair. It was a miracle that they were still at work, except that the thundering tones of Burke found them here and there, and struck them like a whip, shouting orders; he was like an enormous voice of social conscience which forbade them to give up the struggle while there was breath to draw. He kept them at their work as a ship's captain may keep his crew at the pumps even while the vessel is sinking helplessly, and the sea lapping over the deck.

Wherever her eye fell, it found him. When she pulled hopelessly at a small shrub, a hand uprooted it for her with a single jerk. That was Burke.

Then some one held Michael Rylan by the nape of the neck like a wet rag of humanity, while the detective found his key and unlocked the handcuff that still dangled from Burke's wrist.

Again a giant mauled with some clumsy, edgeless tool at the base of a stout sapling, until the tree fell. And that was Burke.

Some one was using strips of bark and interwoven slender branches to fasten the windbreak together solidly. And that was Burke.

A side-wash of wind-driven snow almost overwhelmed the fire and reduced the place to darkness until some one lifted the embers and brought them to sudden life again. And that was Burke.

Now they all sat or lay in the shelter of the windbreak, exhausted by labor and fear. It was Burke alone who fed the fire until the flames rose in a yellow riot from which the wind flung the heat away in savage waste. He stood with his legs braced. His coat, his trousers, were torn in a dozen places where the shrubbery had put teeth in the cloth; and the fire which he had entered two times had eaten great holes and chewed at the edges until he was a man of rags.

HE was giving orders, pointing out his words with a stern hand

of command. They were to take off shoes and stockings; they were

to get off their clothes bit by bit and wring out the water. The

nerveless hands of Katherine obeyed, and to right and left the

others were dumbly obedient. Only the artist, J. Bash tic Id

Rogers, lay back with his arms thrown out crosswise, utterly

spent. Burke took him by the shoulder and shook him until his

head flopped about crazily. Then Rogers was sitting up in his

turn, wearily dragging off his coat to follow orders. They were

all like children, or like a squad of raw recruits, bullied by

the corporal.

Then some one said: "He's gone! Where is he? Where has he gone?"

Katherine, looking up from her bewilderment, saw that in fact Burke was no longer before them; and suddenly it seemed to her that the wind howled with a louder voice, screaming closer to her ear; and the windbreak shook as though it were about to fall; and the wind-driven flight of the snow boiled past them thicker than before.

Mike Rylan stood up and threw out his hands in a gesture of utter despair, groaning: "Has he found a way out? Has he left us in the lurch?"

Then a sharp voice answered: "We'll do as well without a criminal to lead us, Rylan!"

That was Rollie Davison. He grew taller in the eyes of Katherine as she stared at him, but there was no lime even to admire her man. The deep, shuddering groans of the co-pilot drew her to him to give him what ease she could. Wood lay on his back, turning his head in a regular rhythm from side to side, as though he were continually saying no to the world. His eyes never were quite shut, never fully open, so that his face was half blind. All the mind was gone from it, for the pain and the shock of his injuries had driven him quite out of his head. The flames had burned one cheek badly, and his forehead burned with fever. She brought a ball of snow, put some of it inside the handkerchief, and so made a crude ice-pack for his head, holding it in place carefully. She had an instant reward. The groaning lessened; the head presently was still. Something stirred in her as deep as her heart, for it was as though her hands were touching and cherishing the man's life. As he grew still, and the groaning changed to a pitifully audible and deep breath now and then, she looked at the other injured. Both of them were conscious, with open eyes. In those of the stewardess she saw the steady tension of pain. Hardy, the pilot, kept a blank face. The gray color gave the only hint of his torment.

"Tell me what to do for you," she begged the girl.

"I'm all right," answered the stewardess, and managed a brief smile. "I'm all right," she repeated. "Don't leave poor Ken Wood. See if Hardy—"

BUT a sudden outrageous howling of the storm drowned the last words. Then several voices exclaimed; and Katherine, turning her head, saw Burke come striding in through the storm, a figure as white as the flying mist, at first, and then his own burly self was in the lee of the windbreak, brushing the snow out of his hair and shrugging the cold out of his body. The icy air had turned him blue. He stood reaching into the flames, as it were, opening and shutting his hands to bring back blood and sense into them. Under one arm, the sole trophy from this excursion into the wild night, were a number of small sticks which he must have cut from the ends of branches. The other men watched him with curious blendings of fear and resentment and awe in their eyes.

Davison got up suddenly and advanced into the snow-smother as far as the fringe of the brush. There his shadow could be seen wrenching the smaller branches from a dead tree. Patterson finally went after him to help gather the firewood.

Burke went over to the fat co-pilot, sat down cross-legged, and took hold of his wrist, feeling for the pulse; when he found it, he closed his eyes and counted, nodding his head a little. It was something like seeing an ape sit down to think, Kate felt. The same hand which now fingered the pulse of Wood, marking the ebb and now of the life-stream, also had held a gun and murdered Charles Whitley. Murderers are not like other criminals, her father had told her; they are not victims of habit, but simply people whose balance-wheel runs slower. Emotion tips them out of the normal poise too easily. Momentary insanity turns them into beasts, and like beasts they kill. Perhaps in some primeval state of society their value would be greater than the danger from them.

On this night, for instance, except for Burke, two lives would have been lost in the plane; except for Burke, the rest of them probably would be huddled together in a vague heap for warmth, waiting for certain death. In Burke's account it might seem that a balance could be struck in his favor because he had taken from the world only one life and given back to it all this group. But the law, she knew, did not work in this manner. When at last he stood for trial, if he and the rest of them escaped from starvation and cold in these mountains, the entire jury would know about his heroism, and they would recommend him to the mercy of the court. Perhaps he would receive mere sentence for manslaughter. Ten or a dozen years later he would emerge from prison. Perhaps all the rest would have forgotten him. But Mrs. Roland Davison would not forget. With a calm patience she would give him help as long as he lived. During the prison years she would write to him once a month. Perhaps it was the thought of her own enduring virtue that choked Katherine a little; and tears of strange pleasure stung her eyes.

A WOMAN'S voice said: "How is he?" Maureen Ervan was bending

over Wood and Burke. AH the smartness had been drenched and then

wrung out of her clothes. Her bobbed hair hung in straight dabs

around her face. But she retained her brilliant eyes and

too-vivid cheeks; even now she would take the eyes of men who did

not pause to see the mingled voluptuousness and brute about her

chin and mouth. With a startled interest, Katherine watched the

two, the murderer and the cause of the murder.

"Can I help, Jimmy?" asked Maureen.

Burke, rolling back his head to look up at her, started to answer, but checked himself on an unspoken word. For an instant his lip remained with an upward curl so that the teeth showed, like a dog about to bite, and too savage to give warning with even a snarl. Then he lowered his head.

"Ah, damn you, then!" croaked Maureen in her husky voice, and was gone.

The heart of Katherine was racing in her throat. Murder had been only a word to her; but now she had seen in the look of Burke the very face of it. If he were alone with Maureen Ervan in this wilderness, how long would it be before his hands found their way to the throat of the woman whose testimony was to end his life?

"What's your name?" demanded a harsh voice.

That was Burke speaking to her. He had blue-green eyes set well apart under a spacious brow. He was looking at her with a sharp but intelligent consideration, such as a doctor in a charity ward gives to a patient.

"I'm Katherine Lawrence," she said.

"That fellow—the handsome lad. Do you belong to him?"

"He's Roland Davison," she answered.

"Is he?" asked Burke, and deliberately read her face from left to right and from right to left. He smiled a little, and the smile said that he did not think very much of Roland Davison. "You're doing a good job with this one," he added, nodding at Wood. "You've got him asleep. You've got a pair of hands. Keep on using them."

IN winters, when Katherine was not riding, she did a good deal

of gymnasium work. That was to do proper honor to the body which

God had given her. Also she had learned to watch the way people

move. That was why she noted that when Burke rose, he did not

touch the ground with his hands. He stood up as a big cat might

rise, with effortless ease. Then he was crouching by the chief

pilot, Hardy. Katherine followed him with intense eyes; and it

seemed to her as though she were making a swift journey on wings,

not through space but through the mind and spirit of this

man.

He was bending down, staring closely at the stone-colored face and the open eyes of Hardy. It was one of those true Yankee faces, lean of cheek, big of bone, and the straight lips had a good grip, one on the other. It was not a face full of large mind and gentleness of soul, but resolved, keen, eager as if for action even during this moment of complete immobility.

"Your name is Hardy," stated the criminal. "How are you, Hardy?"

The lips of the chief pilot parted after a moment.

"Right as rain," he said.

"You lie," answered Burke. "How much you're lying, I don't know. But you lie. You're hurt. You're hurt so that you can hardly crawl. You can't even crawl, or you'd be working on the others. It's taking all your guts to keep from groaning.... Am I wrong?"

"You're wrong," said Hardy, and looked him in the eye.

THE wind, fallen away to distant uproars for the moment, came

rushing back with its many voices, making a noise like the

rushing of seas around the trunks of the trees and a whistling

shriek through the branches; and all the while, a deeper

vibration like the rumbling of approaching drums came out of the

distance, the sound of a whole army charging tumultuously,

without order. The height of this confusion whirled away and left

Burke still staring down into the level unflinching eyes of

Hardy.

"Listen, old son," said Burke. "You're worth all the rest of 'em put together. All these females multiplied by ten; and all the men—they're not worth a damn compared with your little finger.... So tell me the straight of it. How are you?"

The lips of Hardy parted again, slowly.

"Right as rain," he said.

As he spoke, he smiled a little. Still for a moment Burke studied him dubiously. At last he said: "O.K. I've got to take your word for it. If things get too bad for you, will you sing out?"

"I'll sing out," said Hardy.

Burke stood up, gave a last look to the pilot, and then turned away; but the girl knew that he carried with him a weight of sympathetic understanding. Somehow there was a profound bond between the pilot and the murderer, a pull like that of gravity, a spiritual force that tied them together. And Katherine fumbled far into her mind, trying to understand this evaluation which classed her with all the rest of the passengers and the crew as mere nothings, mere trivialities which, heaped all together, did not compare in value with the pilot's life, and the soul behind that long, hard, narrow face. Of course she revolted against that judgment; and yet an odd instinct kept alive a voice in her that said Burke might be right. She dared not listen to that voice....

Burke was tossing off his coat, tearing off shirt and undershirt, and tearing them into strips. Through coat and shirt and undershirt the fire had eaten its way, here and there, into the flesh. On breast and back she saw the angry red spots. Some of them were blisters which had broken, and the wounds were weeping. She understood, now, that a dozen spurs of anguish were constantly in the flesh of Burke, but he was covered with such big waves and running ripples of muscular strength that the torment seemed a light thing, a triviality, a conversational gesture. Any one of those burns would have put her in bed, she was sure, with a rising temperature and sedatives to strengthen her nerves against pain; but to Burke they were as nothing, his strength of body was so great to her eye. But that negative voice inside her which kept denying her outward judgments was wondering if his bigness were not a matter of sheer spirit.

He said to her, as he worked to tear up the cloth: "Get the broken leg of Alice Gordon bare. Get the stocking off it. Go easy, but get it off."

Mrs. Patterson came to help, and kept reaching out her hands toward the work, but actually her fingers could not be brought to touch the injured leg; and she kept exclaiming under her breath: "Poor child! Poor thing! Poor dear!"

There was something oddly familiar about the exposed leg, to Katherine. It was a moment before she realized that it was like her own, with a knee such as sculptors carve out of their fancy but almost never see in the flesh; for it was not knocked inward, not softened out of shape by a thick padding of flesh inside, but made neatly and clean and small. It was almost shocking to Katherine that such beauty of body should be united with a mere saucy prettiness of face.

Now Burke was wrapping cloth around that small bundle of straight sticks he had brought in from the woods. The cloth would keep them from cutting into the tenderness of the flesh.

"Are you ready, Alice?" he called, as he dropped to his knees.

"Ready!" she said, through her teeth.

HE took her bare foot by the toes and the heel. His fingers

gripped firmly, sinking into the tender flesh and the fragile,

small bones of the instep.

"Hold her at the hips, both of you!" commanded Burke. "Both of you hold her. Ready—go!"

The leg below the knee was twisted at a sharp angle where the break had occurred. In spite of the shattered bone, Burke jerked back suddenly with such strength that the weight of the stewardess was pulled sharply forward in spite of the resisting hands of Katherine and Mrs. Patterson. A scream burst from the throat of the tortured girl, and died half uttered. She had set her teeth over it, as Katherine saw through the swimming darkness that whirled in front of her own eyes. Katherine felt that she would faint. What kept her from that collapse was the hot anger that burned through her whole body, and the bitterness of her revolt against Burke's brutality. Only a sadist could have given the leg that heartless wrench. Yet it seemed to matter nothing to Burke, now. The bone of the lower leg now was straight. He set about the arrangement and bandaging of the splints as though nothing of the slightest interest had happened.

He began to run out of bandages. Kate stood up, reached under her dress, and tore away her slip. He accepted the silken garment without a glance, without a word of acknowledgment, and began to rip it into strips for the bandaging.

AT last they slept. Fear is exhausting, and extreme cold drains away the strength. Shock, also, left them weakened. So they slept.

Katherine, in the arms of Davison with her head on his shoulder, was unconscious for a few minutes, and wakened as he, in his own sleep, kept pressing her closer, not for love but for the warmth of her body. Even that closeness could not keep the cold away. Her side which was farthest from Roland was as chilled as though a bucket of ice-water had been doused over her a moment before.

Still the fire, like a great yellow flower of inexhaustible life, kept blooming in the middle of the storm. She sat up, shuddering, unclasping the arms of Roland.

The others lay heaped together, stirring wretchedly in their sleep. But the fire burned as though it were immortal; and then she heard a voice singing, broken by the howling of the storm.

That was Burke. He was over there sitting beside the stewardess, and his bass voice picked up the lowest note of the storm's orchestra and prolonged it into words. He was singing a song which cattlemen know and use when the steers are bedded down, so that the monotony of sound will soothe the sleeping animals, the dark mounds of flesh which at night on the trail are so many lumps of potential dynamite, ready to stampede at the first alarm.

Roll along, little dogies, roll along;

Keep a-drifting, drifting like a song.

There's a barn chock full of hay

At the end of the way; Roll along.

Little dogies, roll along—

Katherine went closer. She heard Alice Gordon say: "Go on and sleep, big boy. Go on and sleep. I'm all right."

He was not sitting up, after all. Actually he was half reclined, and he had one arm under the head of the stewardess in lieu of a pillow.

"Stop talking, Alice, and try to sleep," answered Burke, and sang another stanza of the old song, keeping vague time for it with his free hand, which stroked the head of the girl. It was love, no doubt, thought Katherine. What else could it be but love? Perhaps there was in the soul of the girl something as unexpected as the beauty of her body; otherwise surely it was a long descent from the man to the stewardess.

Katherine was astonished by the surety of her feeling; for how could it be a descent from a murderer to any woman? This gentleness he was showing was merely the velvet over the tiger's claw. It was merely that she recognized in him a great force, perhaps, and for the force would have selected some larger destiny than Alice Gordon.

AN outbreak of snoring made her look aside, where Mike Rylan

and J. Bashfield Rogers had been driven by the cold into a close

embrace.

The same cold was drawing her, shuddering, to the edge of the fire; but she could not help smiling.

The voice of Burke, deep as the rumbling note of a bass viol, still was singing like a musical thunder:

Step away, little dogies, step away;

There's a trail-end a-coming and the pay.

There's a stockyard and a train

And we'll never meet again.

Step away, little dogies, step away.

And the stewardess was sleeping, with her face turned toward Burke, and the pain smoothed from between her eyes for the first time. He began to inch his arm from beneath her head, moving it with infinite caution. It was plain that whole minutes would elapse before he was free from the girl.

WHAT was the mysterious source and fountain of his strength?

It seemed to Katherine, as she turned away and looked past the

fire, that with his sole hands he had erected the windbreak which

saved their lives; and certainly he alone had tended the fire

during this time of freezing and sleeping.

What was he? All turbulent male? There was enough of that in him for murder, to be sure; but there was also enough woman in his hand to enable it to charm the injured girl to sleep.

Katherine looked away from the fire and tried to free herself from the strange problem which made a tightness about her heart. The storm was more visible now. She could not say that it blew with less violence, but she could look far deeper into it, through the ranks of the trees toward the emptiness that lay beyond them. Down the slope a valley must lie; and in the light of the day which was dawning, perhaps she could bless her eye with the first glimpse of some village beneath them. Even a single house would be to her more than a single star in heaven.

She left the fire. One step from its radiant heat, the cold drenched her to the skin, as though with a violent sluicing of freezing brine; and then the wind got behind her and lifted her into long strides, as though she were about to be blown away. So she came through the trees. At the last rank of them, she was about to take another step—and discovered that the ground had disappeared from beneath her foot.

Fear dropped her to her knees. She lay flat, grasping an exposed root. Her face was above a boiling emptiness, like steam out of the spout of a vast kettle. Right beneath her the rock dropped away in a straight wall of cliff, veined with ice here and there. And through rifts and openings in the wild breath of the storm, she saw a valley as barren as the valleys in the salt sea.

It was all the grayness of stone and snow and bits of woodland like smoking streaks of spray between waves of the ocean.

She drew back. Her knees shook as she pulled herself up beside the tree and leaned there a moment. The strength was so gone from her that she let the wind press her against the trunk, and the cold came out of it into her body and into her heart as the cold of a frozen iron comes into the hand on a winter morning.

After a while she went to the left. The light increased every moment. Over the edge of the cliff she could see clearer glimpses of the valley. There was no life in it. There could not be life within hundreds of miles of such a place? it seemed to her. It was an Arctic region. The face of it made her think of the death of men laboring toward the frontier.

And now, from a projecting point, in the clearer light she saw the cliff sweeping around in a great arc both to right and left, until it joined to tumbling sides of the mountains. There might be ways down from the place, but it would take real mountaineers to find a trail and use it.

Still, the valley beneath them seemed suddenly less desolate. It would serve at least as a road toward succor. Here above the cliff they were fastened to a perch too high and cold for the hawks and the eagles, even.

She turned and went back to the camp. Her way was easier than she had expected, for with the coming of the day the storm lifted a little, and now was shooting the clouds in sooty masses off the tops of the mountains. The wind-pressure along the narrow plateau was much more mild as a result.

SHE found the camp alive and alert, and thoroughly miserable. Hunger had been far less than their fear when they lay down to rest, but it was an equal part in their torment when they roused themselves again. The gooseflesh was visible in the blue of their faces; and they all too plainly felt what Katherine herself was feeling—a cold stone in the vitals, eating away the needed warmth of the blood.

She came back to huddle for an instant at the fire. Davison, stepping up from behind, put his arm around her. She looked up into his face with a sudden hope.

But he was saying: "Where have you been, Kate? Why did you leave me? Stay close to me from now on."

She looked down at the fire again. Perhaps he would think it a nodding of her head in agreement, but there was something in his words which she could not answer. Then he was gone to drag in more wood; and she turned to give the injured what help she could.

Burke was there before her.

"Have you seen—out there?" he asked.

"I've seen," she agreed.

"You haven't talked about it," said Burke. "That's right. Keep what you know behind your teeth, and everybody will be better off. Some of these people are going to be jittery if they find out that we're behind a fence as well as out on a limb. .. . Take a look at Hardy for me and see how you think he is."

She went over to take a look at Hardy. He had that same stone-color in his face and an added tinge of blue in his cheeks. Whatever his secret feeling was, his lips were pressed together to keep it from escaping. She took his wrist. It required some effort and infinite delicacy of touch before her freezing fingertips could find the pulse. At last she recognized the pulsation. It was regular enough, and not very fast. Perhaps the weakness of it was merely apparent and not real, due rather to the cold which numbed her sense of touch rather than to a failing heart.

SHE went back to Burke to give that report, but found him

shouting: "Everybody out: Out in the open! Get out from the trees

and form a line."

Roland Davison dropped a heap of brush he was bringing in and answered: "Burke, you've been doing good work. You've been a handy fellow. But you're not in charge of the party. We'll have no more orders from you, Burke!"

"Won't you?" answered Burke.

"I've told you my mind," said Davison. "Rogers and Rylan agree with me. Keep in your place from now on, Burke."

He spoke calmly, in a clear voice, as he always spoke when there was an emergency. Katherine found herself looking anxiously from one man to the other; but there was no savage outburst from Burke after being checked in this manner. He seemed rather grimly amused than disturbed.

"Have it your own way, then," he said. "But listen! Kate, Patterson-come on out with me!"

"Stay here, Katherine!" directed Davison. "You're not at his beck and call."

"But listen! Listen!" cried Katherine suddenly.

She could hear it now. It came through the grain of the storm's noise like a saw-through wood, the whirring sound of strong motors above them, in the clouds.

There was no need for Burke to repeat commands, after that. All the group went storming through the trees and out into the open flat of the plateau. By the time they were clear of the trees, the noise of the motors was just above them.

"Form a line—hold hands and form a line!" shouted Burke. "And walk forward so they can see us move."

They formed the line, obediently. Katherine had the hand of pretty little Maureen Ervan on one side, and Davison's on the other.

Ruth Patterson screamed out: "Look! Look! They've seen us! They're coming!"

And in fact the plane, like a clumsy stiff-winged bird, dropped out of the higher clouds at that moment. But it was not coming. It was receding, and in another instant a cloud sponged it out of the face of the sky.

Maureen Ervan broke from her place in line and ran after the disappearing hope which had looked at them from the sky and turned away again so quickly. She ran, screaming hoarsely, holding out her hands, until she stumbled and fell to her knees with her face caught between her hands, her body swaying from side to side as she sobbed.

"We've got to get a fire out here in the open," said Burke. "I'm a fool not to have thought of that."

A crazy passion came over Mike Rylan. He shook his fist in Burke's face and shouted: "Save your thinking till you're in the death-house where you belong! There's other people here to do the thinking!"

HE seemed to realize that this sort of talk might be

dangerous. Before he ended the words, he was backing up and

pulling a long-barreled gun from his clothes; but Burke made no

gesture toward him. The big man had swayed forward a little as

the words struck him; he seemed in the very act of springing at

Rylan, and then something checked him on tiptoe and settled him

back on his heels. Somehow Katherine knew it was not the mere

sight of the gun which made him hold back. There was more than

brute in him, then; there was the thin silken leash of reason, as

well.

Afterward he hurried to bring out burning brush from the fire in front of the windbreak, and on the level snow he deposited it. Katherine herself helped to bring more fuel. They built the flame high. Then green branches on top sent up a thick column of smoke that boiled up aslant through the sky.

It looked to Katherine like an endless arm held up to arrest attention and summon help.

EVERYTHING at that moment conspired to raise their hopes in spite of the disappearance of the airplane, for the wind changed direction a little and lifted still higher from the earth, splitting the clouds apart and tumbling them like a great furrow down the sky. Katherine, dragging more fuel for the fire, looked up, agape with joy, at the blue of heaven and the bright sun that poured down over the mountains.

Davison appeared beside her and laid a hand on her arm.

"Let the brush alone, Kate," he commanded. "We'll end in a disaster if we let a common murderer give the directions in our camp. Do what Rylan or Rogers tell you. Or you can take my own advice. But stop trotting about like a puppy at the heels of Burke. I should think your own good sense would warn you not to do that!"

She had dropped the branches she was dragging, and looked down at the hand on her arm while he spoke. Then, silently, she lifted the hand, picked up her burden, and trudged on toward the fire. It was not until she was tossing the branches onto the burning heap that she realized the possible significance of what she had done; and glancing back, she saw Davison still in place where she had left him. Only then did she realize that she had taken what might be the longest step of her life, if she persisted in it. It seemed to her a temptation to evil, and gave a guilty lift to her heart; but all the while she was assured that nothing could be broken off, and that in the end, if they lived, she must go on to New York, where that formal wedding, like a state ceremony, awaited her. Then with the farther lifting of the clouds, she saw a picture that drove all other thoughts from her mind.

For all the mountain peaks in the same instant were revealed with the brilliancy of the sun on them and the wind flaring out behind their heads long banners of snow-dust. Sometimes where the windward slope of the mountains was very steep or almost concave, the snow rushed upward like an endless explosion, hanging vast clouds of radiance in the sky; but as a rule each summit wore its flag of translucency, its flying veil of sunshine made visible. There was such a dazzle of beauty, such a glory over the white mountains, as though they were keeping a festival and rejoicing together. The wind, singing high above them, was the voice of that ecstasy.

She looked away from the heights, to find that all the rest were down-headed with their thoughts; only the murderer, Burke, looked up toward the mountains. And even he had something more than scenic beauty in his mind's-eye, for now he was calling Mike Rylan and pointing.

She saw what he meant a moment later. High above them and far away on a ledge of the upper cliff, a huge mountain sheep had come out to the edge of the precipice to look over the morning. The hunger which had been gnawing at the vitals of Katherine rose upward and threw a spinning darkness across her eyes.

She saw Davison come with high, floundering steps through the snow; Patterson was there, also, and Rogers, all pointing and staring at some two or three hundred pounds of meat on the hoof; and then Rylan's automatic was in his hand. Still more talk, and finally the gun was passed to Davison.

She felt a pride that lifted her head. They had heard, then, of the big-game hunting of Roland Davison, and they gave way to him. Only Burke, now standing somewhat aloof from the rest, called, as Rylan and Davison started away: "Careful, boys. There's a lot of loose, soft snow on this side of the mountain. Watch your step."

Davison turned silently, gave Burke a careful look, and then went on with Rylan.

The others gathered closely together to watch the decision upon their fate. Hunger does not kill very quickly, but at the end of three or four days it paralyzes even a strong man with weakness. Up there on the ledge was salvation for them all, if Davison could make the shot.

RYLAN and Davison, swinging off to the right of a straight

line, seemed for a moment or two to be growing larger against the

snow; then they dipped into a swale and came up on the farther

side as small figures. The spots of darkness which their feet

left behind them seemed almost as large as the bodies of the

laboring men.

Their strategy seemed faultless. They were going to the right, away from the straight line toward the big ram, and now they were cutting in under the edge of the cliff where his lordly eyes could not see them; after that, they could come out again into view of the big fellow and drop him with a quick short-range shot.

Katherine went to Burke and murmured to him—as though a raised voice might frighten the sheep away even at that distance: "Will they get it? Can they get it?"

"They ought to go up high," answered Burke. "A rising shot is hard to make; and then there's the snow; if they start a riffle in it sliding, that sheep will be off like quicksilver."

"They ought to have you with them!"

"They'd rather have me in jail," answered Burke.

She could not speak, after that. Far, far beyond the level of the plateau, and high up the slope at the foot of the cliff, the two little figures were moving. It seemed that they were directly beneath the sheep now. Perhaps they were coming out from under the rock, to make the shot; at that great distance it was impossible to tell.

"I knew it!" said Burke suddenly.

For the big mountain sheep with his curling horns had disappeared now, and where the two little black figures stood rose a puff of white smoke, barely discernible. She thought at first that it might be smoke from the gun, before she realized that smokeless powder would leave no stain in the air.

A FAINT cry came from the other watchers as they saw the

mountain sheep disappear; but even that universal exclamation was

muffled, all had been watching with such tense hope. The white

rising of the snow-dust, like smoke, continued and increased. The

two hunters were lost behind it. And still the dust grew until it

was like a flag, blowing straight up from the ground and

advancing with increasing rapidity.

"It's a snow-slide," announced the calm voice of Burke. "Get out of here, and get fast!"

He led the way at a dog-trot to the right. The rest, hesitant for a moment, floundered slowly after him. Katherine he held by the right arm, high up close to the shoulder. When she looked back across the level of the plateau, she saw that the slide had gathered head and speed with wonderful rapidity. Gathering mass, it now was cutting down through the snow to the soil and rock beneath, and left a widening V of darkness as its path. Well above, she saw at the apex of the inverted V the two little figures of the men.

"This ought to be far enough," said Burke, and let her halt and turn back. The others, thoroughly panic-stricken, went by them like a covey of quail.

For the snowslide was showing both a face and a voice, now. Its front was a wild white wave that careened down the mountain as fast as a galloping horse, flinging up small dark objects as it ran, like a juggler with a thousand hands. Those would be the rocks and boulders, which it caught up with the bottom of its flying plowshare. Its voice was like a wave also, an endless breaker roaring on an endless shore and rushing momentarily closer.

From behind it the flag of snow-dust shot up continually higher in the air. Now the whole mass, striking a swale, veered off and headed almost toward Burke; again it plunged against a hummock and knocked a spray of snow-clots and boulders a hundred feet overhead, then swayed to its right again, and changed its voice as it struck the level of the plateau.

It seemed to Katherine that the mass must stop there on the flat; but it ran on like something on wheels with hardly arrested momentum. It reached the down-slope on the farther side. It struck the trees with a sound like a thousand axes, and a thousand tree-trunks fell. Instantly stripped of bark and limbs in the wild mill of the slide, white, glistening tree-bodies leaped into the sunlight like great silver fish out of a tidal wave.

And then silence.... The slide had reached the edge of the lower cliff and plunged forth over the valley. It was gone, and only the echoes boomed close by and then echoed far away, rattling among the higher peaks. Their voices had not died when a huge report boomed up from the valley floor, followed by an instant of rushing noises. The last echoes fondled these sounds. They died. The morning was left as before, with those wild white banners streaming from the mountain tops. And two little figures, incredibly small, almost invisible as they toiled down the rough path of the slide, were returning empty-handed to the hungry people.

"They've lost the gun," said Burke. "They've lost the gun, or they would have gone on, anyway.... The sheep knows it, Kate. Look up there!"

As a matter of fact, three ledges above the place where it had first appeared, the little silhouette of a mountain sheep appeared against the crystal radiance of the blowing snow.

And the automatic was gone. It seemed to Katherine, as she went down-headed back toward the trees, that a great event had happened in history.

MIKE RYLAN, filled with excitement, was trying to tell how the

slide had begun, how the snow had slipped, suddenly, beneath the

feet of Davison. How the whole slope had turned to water,

carrying them swiftly along until a projection of rock held up

its hand and stopped them. How they had lain there flat on their

bellies and watched the white monster come to life with

increasing strength and begin to plow its way down the

mountain-side. But Rylan had no good listeners. Only one thing

was of importance. This present failure could have been forgiven

a thousand times over; but Davison, as the snow shot away beneath

him, had let the automatic fly out of his hand.

Maureen Ervan caught him by the coat-sleeve and croaked into his face:

"You've thrown our lives away. Oh, you fool, you damned high-headed fool, you've thrown us all away... Go jump off the cliff!... I wish you had never been born!"

Maureen was the only one who put thoughts and wishes into words. The others said nothing, but they looked at Roland Davison as honest men regard a traitor. She heard big Patterson say: "Burke should have gone, of course. The only luck we have is what Burke gives us!"

Then they were back at the camp, where Hardy continued to look into upper space, silently, and his co-pilot, Wood, once more out of his head with pain and his injuries, kept turning his face from side to side, groaning on every indrawn breath. The stewardess, flushed, bright-eyed, enduring, had her head lifted by Burke, who was giving her a drink of snow-water, melted in a twisted, hollowed fragment from one wing of the wrecked plane.

Burke lowered her head and stood up before them.

"Get back there in the open!" he commanded. "Three or four of you get out there and stay out there. Keep that fire hot, and keep feeding green branches to make the smoke. That's the one chance we have of making a signal. And unless a plane lands for us on the plateau, most of us are going to die right here. Does that make sense? Die right here, unless we have wings to fly away. We'll have no more arguing about it Rylan, you and Rogers and Mrs. Patterson can take the first watch out there by the fire. And if there's any back-talk and delay, I'll have to use my hands on you—and I'll do it! Get moving, the three of you!"

IT was not the trio that Katherine watched, but the face of

Davison as he stood up ready to protest. Rylan and he, for an

instant, eyed one another gloomily. But no action followed.

Rylan, Mrs. Patterson and Rogers moved off through the trees.

But they had an almost hopeless task ahead of them, for suddenly, like the closing of the door of a bright room, the brilliance had gone out of the sky; and with the disappearance of the sun, the clouds rolled lower down, the wind dropped closer to the earth, and changing to its old quarter, began to blow the mist of snow-dust through the trees. A false gray twilight covered the world.

With blistered, weary hands, Katherine started once more moiling and toiling in the brush to get more fuel for the fire. But the dead bushes seemed to have been exhausted already. She had to go farther in among the trees. And the wind cut through her torn clothes as though she were a naked body. She was tired of dreading death; she was too exhausted to feel fear. And when she stood, carelessly, on the edge of the precipice with the smoking valley far beneath her, it seemed an easy thing to make that one brief step into nothingness.

ONE freezing hour tending the fire on the open plateau was all that flesh could stand. The first trio came back. Then Katherine went out with Patterson and Roland Davison, to stand her watch. Burke was gone all that time. He still was gone when they came shuddering back to the windbreak and its life-giving fire. But a moment later he appeared, the wind huddling his coat up around his shoulders and snowing his half-naked body, blue with cold except for the red spots which the fire had left on his flesh.

He sat down by the fire, borrowed a knife, and took from his pocket a creature no larger than a squirrel, with a tiny, delicate head. He began to skin and clean it. He went off into the storm again, returned with a larger section of twisted metal from the wing-sheathing of the plane, heaped this with snow, and when the water was hot, dropped the body of the little rock-coney into the dish to stew. Another and another of those small dead creatures he took from his pocket, skinned, cleaned, and put into the improvised pot.

Where he had found them, how he had caught them, they did not even think to ask. It was sufficient that he had performed the miracle, and the odor of the stew carried a heavenly fragrance to the others as they bent close.

After a time he began to prong the meat with a pointed stick. A dozen of the little creatures were in the pot. He picked up the best done of the lot with his stick and began to scrape the meat from the frame with the point of the pocket-knife. When the frame was clean, he broke the skeleton in two.

"Who needs food the most?" he asked, holding up the prizes.

A hungry silence lasted only an instant. Then Maureen Ervan screeched: "But I'm starving, Jimmy I I'm dying. I haven't eaten all yesterday. Jimmy—Jimmy—darling——"

"Maybe you re a step nearer crazy than the rest," agreed Burke, and held out half the skeleton without touching the girl with hie eyes.

"You take the rest," he said to Katherine.

"There are the sick," said Katherine. "There's Alice—"

He looked at her with strange eyes for a moment.

"The sick are going to have the meat," he answered. "They'll have the soup and the meat.... Take this. Chew up the bones. Chew 'em up small, and they'll do you a lot of good. Chew 'em bit by bit, and mash them up fine. Then you can swallow, and they'll do you no harm.... Take this."