RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

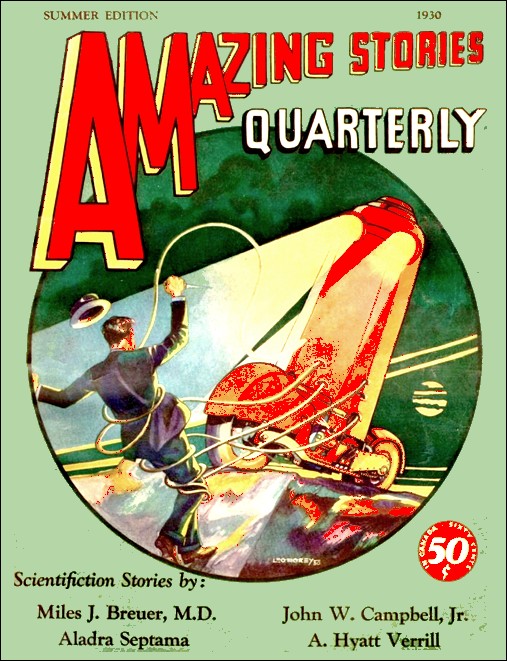

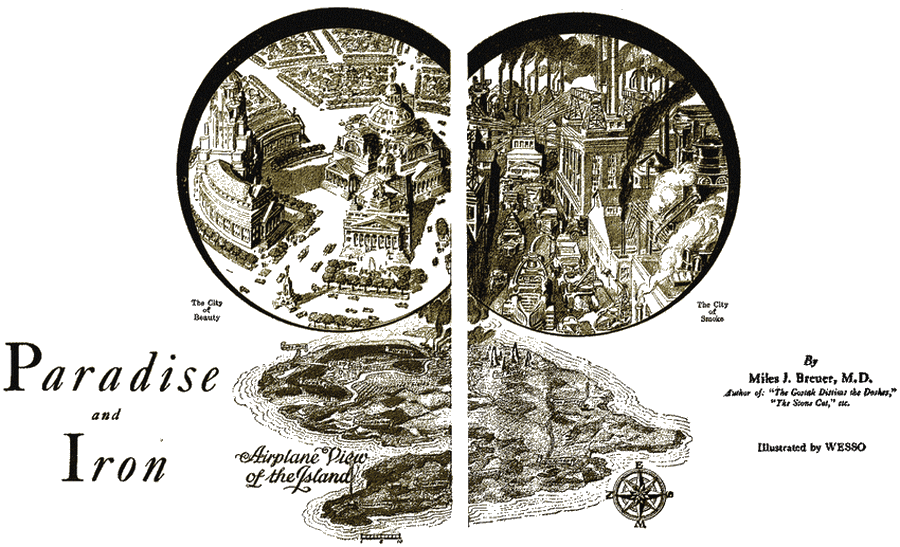

Amazing Stories Quarterly, Summer 1930, with "Paradise and Iron"

The early models of even a brilliant invention are at best only crude affairs, often within an exceedingly short time perfected beyond recognition. This is just as true of the airplane as it is of the automobile and the telephone and numerous other mechanical inventions that we now take quite for granted. For many years there has been much talk about building thought-machines. Even now there are calculating machines that quickly solve mathematical problems that would otherwise take eminent mathematicians and skilled computators months to solve. And constant improvements are being made on these mechanical "robot" mathematicians.

It is a far fetched vision, perhaps, to think of a time when the thought-machine, which now can be worked with very little supervision, might some time get to a point where it can make suggestions for its own improvement—mathematically figured out improvements, of course—but it is not impossible. And if and when that happens, who can forecast the future of mechanical progress? In this complete novel, Dr. Breuer gives us, in good literary style, a wealth of absorbing elaborations on the possibilities of the machine-age, which makes the story one of unusual scientific interest.

WHY anyone so old as Daniel Breckenridge, my grandfather's brother, should keep on working as hard as he did, was a mystery to me. He was about eighty-four; and a million little crinkles crisscrossed on the dry, parchment-like skin of his face where it was not covered by his snow-white beard. But he still went briskly about his duties as shipping manager of a great ship chandler's establishment at Galveston. Just now he whispered sharply to me, and drew me by the arm behind some bales of canvas in the depths of the vast shipping-room.

"Look! There he is!"

He seemed to be trembling with intense excitement as he pointed toward the great sliding doors.

There, watching the men loading up a truck with a pile of goods consigned to some ship, was an old man, just as old and snowy and crinkled, and just as firm and active as my grand-uncle himself. I looked at him blankly for a moment. He was an interesting-looking old man, but I saw nothing to set me off a- tremble with excitement. But my old grand-uncle clutched my arm.

"Old John Kaspar, the Mystery Man!" he whispered again.

That suddenly galvanized me into action. I took one more good look at him, and got into motion at once.

"Do you think you could hold him here somehow until I get my outfit?" I asked. "I'll be back in ten minutes." It was now my turn to be tense and thrilled.

"It will take them longer than that to load up the truck," he said; "but hurry."

I shook hands with him hastily but fervently, knowing that I might have no further opportunity to do so, and then dashed out after a taxi. While my taxi is rushing me off to my room, I can explain all I know about John Kaspar, the mysterious octogenarian.

Forty years ago, back in the days when the gasoline industry was just being opened up, John Kaspar was the richest man in the world. His father had been a manufacturer of automobiles in Ohio and, foreseeing the importance of gasoline, he had bought up half a county of the most promising oil lands in East Texas. Before his death, oil was found on every acre of it. The son John, the old man at whom we have just been looking, was not interested in becoming a financier; he was working out some original ideas in automobile design. There were some wildly headlined newspaper clippings in my grand-uncle's collection, about John Kaspar's having thrown a reporter bodily into the ash-can because the poor fellow had made his way into Kaspar's shop and was looking too closely at some marvelous new invention on an automobile.

Then all of a sudden, John Kaspar disappeared! One morning the world woke up to the fact that he had been gone for two or three weeks. Investigation showed that he had converted all his properties into liquid securities, and it constituted the greatest single fortune the world had ever seen. With it in his hands, this young man, not yet twenty-five years old, was more powerful than the old Kings of France. This entire fortune had vanished with him. There was a tremendous lot of excitement about it in the papers and magazines; it furnished much conversation; running about and investigating, puzzling and wonderment; alarm that he might have met with foul play, and apprehension that he might have some sinister designs on civilization.

But no trace was ever found of him.

John Kaspar's closest friend was my grandfather, just recently died at the age of eighty-seven, having kept up his practice as a country doctor to the day of his death. The two had been roommates at college, and had been together a great deal in the years following their graduation. My grandfather, at the time, had been very much distressed about his friend's disappearance. To the day of his death he had lived in hopes that he would hear from Kaspar again.

The world forgot about John Kaspar and his vanished fortune long before I was born. I first learned of the story something over four years ago, when I was just beginning my work in Galveston at the State University Medical School. My aged grand- uncle had pointed out the mysterious old man to me, standing by the loading-door of the shipping room at Martin & Myrtle's.

"It's Kaspar!" he had said in a vehement whisper. "I can swear it is!"

Then he told me the story of the millionaire inventor's disappearance, back in the early years of the century.

"He first came in here several years ago," he concluded. "I could take an oath that it is John Kaspar. Your grandfather and I knew him more intimately than did anyone else."

He had studied him awhile—this was four years ago—and then shook his head.

"I wonder what has happened to him? He looks worried and sad, though he still seems to have his old iron constitution. There must be something strange going on somewhere—" My aged relative's voice trailed off reminiscently. After a moment he continued:

"When he first came in here, I hurried up to him with outstretched hand, joyful to see him again. He stared coldly at me, shook his head with an apologetic smile. He insisted that he did not know me, and I could not possibly know him. He was very courteous and very apologetic, but absolutely firm in the matter. Why does he hide his identity?

"He has been here twice since then. I followed his loaded truck both times in a taxi when he rode away. He comes to Galveston in a black yacht, black as ink. He has our truckmen unload the goods on his deck, and the instant the last package has touched the ship, he leaves the dock, with the things piled up on the deck.

"Where does he go? Where does he come from? What can he be up to, and where? And I can't forget that gloomy, worried look on his face."

My grand-uncle's account, and the sight of the wrinkled, but upright old man, with white hair and white beard, aroused my interest. And his pitiful eagerness to know more of his old friend aroused my sympathy.

I decided to go. I got together an outfit of clothes, weapons, preserved rations, first-aid kit, and money; and packed it, ready to seize and run at an instant's notice. My two years of service in the Texas Rangers gave me an excellent background for an adventure such as this promised to be.

I was in my Sophomore year at the Medical College at Galveston when we last saw the aged Kaspar come into the ship chandlers' firm for his boatload of supplies. Then for two years my emergency outfit lay packed and ready, inspected at intervals. I had graduated, received my doctor's degree, and was loafing around, resting and trying to decide what to do next.

Then one day my grand-uncle drew me behind the bales of canvas and pointed out our visitor. I did not recognize him at once. As soon as I did, I jumped into a taxi, dashed to my room, seized my kit, which was packed in a suitcase, and hurried back.

My grand-uncle stood there watching for me.

"Follow that truck!" he said to the taxi-driver, which the latter promptly did, nearly turning me on my ear.

The truck led us to a dock at the eastern extremity of Galveston Island.

The black yacht lay there right alongside the dock, just as she had been described to me. She was a trim, swift-looking craft, about a hundred feet long; but her black color gave her a sinister appearance among the bright white ships around her. And there also was the white-bearded old man walking up the gangplank. He ascended to the somber deck, and without looking around disappeared down a hatchway.

Knowing that my time was short, I quickly paid off my taxi- driver and hurried up on the dock. Catching hold of the swinging board with my hands, I scrambled up over the edge of it and rolled down on the deck.

"Now I'm aboard the old hearse whether I'm wanted or not," I said to myself. "If it continues the way it has started, this is going to be a lively trip."

Then the astonishing fact came home to me that there was no one anywhere on deck. Ordinarily the deck of a ship leaving dock is a busy scene, with sailors scurrying about, officers giving orders, and passengers at the rail taking a last look back. This deck might as well have been a graveyard; in fact it had somewhat that effect on me with its somber black everywhere.

A big searchlight in the bows rotated slowly on its pivot until its lens was turned squarely on me, and I caught a distorted reflection of myself in its depths; and then it turned back into its original position. It gave me a creepy, momentary impression of a huge eye that had looked at me, stared for a moment, and then looked away again. In a few moments the ship was slipping along at considerable speed between the jetties, and Galveston was only a serrated purple skyline astern. The small machinery on deck had become quiet; and there remained only the deep and steady vibration of the engines. No one had as yet shown himself anywhere on board. I picked up my suitcase and walked around the deck, up one side and down the other, from bow to stern. At first I walked hesitatingly, and then, as I continued to find no one, I stepped out boldly.

It was a queer ship. Even though my knowledge of ships was limited to what I had acquired during a few years' residence in a seaport city, I could see that it was an uncommonly built and arranged vessel. There was no wheel, and no steersman! The usual site of the wheel and binnacle was occupied by a cabin with some instruments in it; nor could I find anywhere any signs of anything resembling steering gear. How was the ship piloted? Who was watching the course? There wasn't a lookout to be seen anywhere! Yet the ship had picked a tortuous course from its dock down the harbor and between the jetties. A big, wide hatch in the waist led to the engine-room, if I might judge from the hot, oily smelling draft and the hum of machinery that came up through it. So I explored down there and looked the engines over. They were huge, heavy things, apparently of the Diesel type, but with a good deal of complicated apparatus on them that I had never seen on any Diesel engine and of which I could not guess the purpose. Every moment I expected to see a greasy engineer come around a corner or from behind a motor. My curiosity overcame my hesitation, and I gathered up the courage to search all the niches and corners down there, but found no one. Was I to conclude that the engines were running themselves, without care?

The fore-hatch apparently led into the hold, whose gloomy depths were piled with bales and boxes. Obviously, there was no forecastle. No quarters for a crew! Well, all the crew I had seen so far would not require much space for quarters. The captain's cabin was where it belonged, but there was no one in it; only tables covered with apparatus. Gradually my exploration of the ship changed into a frantic search for some human being.

When I paused in my search, it was dusk. The ship was tearing along through the water at an unusual speed. From the high bow wave and the churning wake, I would have guessed it at thirty knots. Galveston was but a faint glow on the horizon astern.

There was one place that I had not yet searched, and that was the cabin just ahead of the middle of the vessel. This was the space usually reserved for passengers on ships of this size. Down there it was that the mysterious old Kaspar had gone. Unless I was to conclude that he was the only living soul aboard, that is where the officers and crew must be. If all the officers and men were shut up together in the passengers' cabin, even a landlubber like myself was compelled to pronounce it a strange proceeding.

I opened the hatchway and looked down. My flashlight showed several steps leading to a passageway several feet below. There were three doors on each side and one at the end; and the latter had a line of yellow light under it coming through a crack. That is where Kaspar was at any rate! I went down quickly, threw open one of the doors, and pointed a flashlight into the room. It was empty. The others were the same. I knocked loudly on the door at the end of the passage. A chair scraped on the floor and the door swung swiftly open. There stood the strange old man, erect as a warrior, but pale with surprise.

"For God's sake, man!" he gasped. "What do you want here? How did you get here? You unfortunate man!"

He clasped his hands together nervously. For the first time it occurred to me that I probably looked dirty and disheveled, from my scramble up the gangplank.

"For the love of Pete!" I exclaimed. "Who is running this ship?"

"If you only knew," the old man said in a melancholy voice, peering at me closely, "the powers that control this ship, you would implore me to take you back. But I am afraid I cannot take you back. I have some influence, but not enough to do that."

"But I'm not asking you to take me back," I protested. "Don't worry yourself about that end of it—"

"You must go back before it is too late."

His voice quivered with earnestness.

"Your only hope," he continued, "lies in meeting some ship and putting you across on a boat."

"I'm not going back," I said shortly. "It was hard enough to get here the first time."

He studied me another moment in silence, and then stepped backwards into the room, motioning me in. I looked about eagerly, but my theories fell helpless. He certainly was not controlling the ship from this room. It had four bare walls, ceiling, and floor; a porthole, a bunk, and a washstand. A traveling bag stood in a corner; a few Galveston newspapers were piled on the bunk. That is all!

"Who are you?" he said patiently.

I related to him briefly who I was and why I had come.

"Then you're not a newspaper reporter nor an oil or copper prospector?"

He regarded me eagerly.

I merely laughed in reply, for I could see that he was now convinced.

"But that does not alter the danger for you," he went on earnestly. "If we do not get you on a ship before it is too late, you will never see Galveston again."

"Sounds bad!" I remarked, not very seriously impressed. "Tell me about it. What will happen to me?"

He sat and thought a while.

"If it were possible to tell you in a few words," he said abstractedly, "I should do so."

He looked out of the porthole awhile, lost in thought. I studied his profile. Certainly the tall forehead and prominent occiput denoted brain power. Through the circular window I could see the waves rushing backwards between the ship and the rising moon. He finally turned to me again.

"So Kit Breckenridge is dead?" he said softly. "And Dan wanted you to come and find out about me? Good old Dan."

"My great-uncle Dan was very much puzzled as to why you denied your identity to him."

"It hurt me to do that. I was hungry for a talk with him. Can't you imagine how I should like to ask him about people and places? But how can I ever talk to my old friends again? I've often thought of trying it. But there would be endless complications."

"I'll respect your secret, sir!" I argued eagerly. "And I shall behave myself on your island, and keep out of trouble."

"No!" he exclaimed. His voice was troubled, and there was a pained look in his kind old face. "I cannot permit you to go to an almost certain doom."

"I've gone to 'em before," I said cheerfully, "and my skin is still all here. I've been in the Texas Rangers, and can take care of myself."

He shook his head. He had been straight and tall when he marched up the gangplank. Now he was bent, and looked very old.

"Now you have seen me and talked with me," he finally said. "You can be content to go back and tell Dan Breckenridge and your father that you have seen me, and that I am well and happy."

"Mr. Kaspar," I said, striving to conceal the impatience and excitement in my tones; "wouldn't I look foolish coming back with a story like that? They know that much already. Besides: you may be well, but you don't look happy to me. You're under some shadow or in some difficulty. I shouldn't be surprised if I could find some way of helping you."

"You cannot!" he groaned. "You are lost! I know the courage of youth. I am glad that it still exists in the world. But that will not avail you. It is not danger from men that you need fear. There are forces far more subtle and more terrible than you can imagine."

There was such an expression of worried anxiety on his face, and he seemed so genuinely concerned for me, that I regretted to be the cause of such distress. He sighed as I shook my head in reply to his last protest.

"I don't mind admitting to you," I added, "that if I were really anxious to go back to Galveston, waiting to meet a ship would not be my way of doing it. You must indeed have been lost to the world for forty years if it does not occur to you that I might call an airplane by radio to take me back."

"Well, I'll have to find you a bed then, as it is getting on into the night," he said resignedly, and beckoned to me to follow him. He led the way down the passage and opened one of the doors. As I entered with my suitcase, he bade me good-night.

I found myself in a small cabin with the usual furniture, a bunk, a chair, a washstand. The bunk was made up with a blanket, and I hopped into it at once, taking only the precaution to take with me to bed my service pistol, a Colt .45 automatic. The ship was quiet; the hum and vibration of the machinery were not disturbing; there was only the splashing of the water outside my room. For a long time I could not go to sleep. It was hot, and I was a little seasick. I tossed around and pondered. The swift, lifeless ship terrified me, now that I was alone in the dark.

Finally the motion of the ship rocked me into a sound sleep. I awoke suddenly and at first was surprised to find the sun shining on me through a round window, and myself fully, though untidily dressed.

Then, recollecting myself, I jumped out of my bunk, extracted a toilet kit from my suitcase, and washed and shaved. I replaced my white collar and creased trousers with a flannel shirt, whipcord breeches and a pair of heavy, laced boots. I put the big service pistol back into the suitcase, but slipped a little .25 caliber automatic into my pocket. By the time I got myself into shape, I was hungry, and went in search of food. I stole softly to the old man's door, and listened. Sounds of deep breathing indicated that he must still be asleep; my search would have to be made alone. Again I hunted thoroughly through the entire ship, the deck and its structures, the hold, the engine-room, and several cabins like the one in which I had slept. There was no dining room and no galley, and not a sign of food. Of course, if there were no people on the ship, it was quite logical that there should be no food.

For a moment, the after deck engaged my attention and made me forget my hunger. The space ordinarily occupied by officers' quarters was filled by masses of apparatus. Through the windows and doors I could see great stacks of delicate and complicated mechanisms, such as I had never dreamed of before in connection with a ship. There were clicking relays and fluttering vanes and delicate gears; little lights would go on and off, little levers would jerk, here and there, in twos and threes and dozens, and then all would be silent and motionless for an instant.

Before I had regarded it very long, hunger drove me to a further search of the ship. Everything was clean and orderly. A peculiarity of the black paint on everything struck me; it had the appearance of the japanning or enameling that is usually found on metal machine parts; it was more like the finish on an automobile than like the paint job on a ship; it gave the suggestion of being machine-processed, perhaps by air brush. And all over the ship there were various bits of mechanical activity: here water running from a hose; there a rotating anemometer; yonder a pump sliding and clicking back and forth. It looked for all the world as though an efficient and well-disciplined crew had left but a moment ago.

The venerable old man appeared about eleven o'clock.

"I must ask your pardon for having kept you hungry so long. It is a long, long time since I have entertained guests, and I forgot. I could not go to sleep till nearly morning, and now I have overslept. Come, you must be hungry; though I have not much to give you."

He led the way to his cabin. I looked it over again carefully, thinking that perhaps on the previous evening, during the excitement of the conversation, I might have overlooked the mechanism by which he controlled the ship from his cabin. But there was nothing there. The most surprising thing about it all is for me to think back now, and realize how far even my imaginative and astonishing explanation fell short of the actual truth.

He opened the suitcase and set out some preserved fruit, meat, and bread for me; and a bottle of carbonated fruity beverage. In the absence of other evidence, the few little jars of food that he had were eloquent enough testimony that he was the only man on the ship besides myself.

When we came out on deck again, it was nearly noon. Kaspar put his hand on my shoulder.

"Last night I urged you to go back," he began. "I was tired after a strenuous day, and I allowed you to dissuade me from my purpose. Here is your opportunity. We can signal the ship over there, to take you."

"I'm not going back," I said calmly. "I know it is rude of me to force myself on you, and I apologize; but—"

"My dear boy, that is foolish. You know that my only concern is for your own welfare. Personally, I like your company. You remind me of my young days in Texas. For other reasons, that you could never guess, I should like to take you along. But, for your own good, your career, your friends and loved ones—"

"You speak as though this were my funeral," I interrupted.

"It is certain that you will never get back. Knowing what I know—not even many of my own island people know it—I can see clearly that you, of all people, will be in serious danger upon the island."

"Why can't I come back to Galveston with you on your next trip?" I urged.

"Who knows where you or I shall be by that time? I may never live to take another; and you—inside of a week, a young fellow of your type would be a marked man on the island."

"What is the danger?"

"I am not even sure myself. I only know that many brave and brilliant people have disappeared forever. Your world needs you; it needs brains, courage, and skill, and you seem well gifted with all of these. Our island does not need these qualities."

His argument did not sound convincing to me; it looked too fantastic to be real. For that matter, has anyone ever been convinced by spoken warnings of a vague danger? Has any old man's warning ever stopped a young man's headlong rush?

"Listen!" I exclaimed. "You have said that you do not mind my company personally. I am therefore going to stick to you."

"But, Davy! I cannot have it on my conscience that I was the cause of you—the cause of a horrible end for you. I am troubled enough about the others, for whose doom I do feel responsible. Come—"

On the previous night, all alone in my bunk in the darkness, I had felt some misgivings and some fear. Even an hour before, what with solitude and hunger, I might have taken advantage of an opportunity to flee. But this old man's face and bearing showed that he was carrying some heavy burden of trouble. A first glance showed that there was wisdom, intelligence, and ingenuity there; and the most careful scrutiny could show naught but kindness, benevolence, and sympathy. The mere sight of his face strengthened my resolve to see this adventure through.

Kaspar sighed, as though he were glad that he had done his part and that it had come out this way.

"You're a good boy," he said. It sounded very affectionate and quite old-fashioned. Then, after a few moments' silence:

"You do not have a wife and children at home?"

"Nobody!" I shook my head vigorously at the strange sound of it.

"I suppose it is all right," he murmured, mostly to himself; "One person more or less on the island—what does it matter?"

We met no more ships, though several times we saw smoke in the distance. A number of times we sighted land; now high and rocky, and again flat and sandy with tropical vegetation. From the direction in which we went and the tremendous speed that the boat was making, I concluded that we would soon be in the Caribbean Sea. After I had given up hope of making the old man talk, I sat and watched him staring out over the water. No question about it: he was totally oblivious of any responsibility for navigating the ship.

Toward six o'clock in the evening of the strangest day I ever spent, I saw a light blue line of haze, straight over the bows. This grew darker and more solid as the minutes went by; slowly it broadened and darkened and spread out on both sides of us. So great was the speed of the ship, that it was still twilight when we drew close enough for me to see a row of pinkish granite cliffs in front of us, extending as far as I could see on either side, with a haze of black smoke high in the sky behind them. A volcano? I wondered. The tropical night was closing swiftly down as the ship tore through the water at unabated speed. Nervously I stood on the deck and searched for some sign of a harbor or a landing-place. Every moment I expected the ship to swerve to one side or another. I began to get worried—for the ship plunged straight on toward the wall of cliffs.

AS the darkness rapidly gathered, three searchlights in the bow blazed out, lighting up the rocky wall ahead into an intense relief of brightly lighted cliffs and inky black shadows. Straight ahead of us there was a cleft in the rocks, an irregularly vertical band of Stygian blackness, extending from the water up as high as the rays of our searchlight fell.

Then, I suddenly grasped the remarkable fact that though the breakers roared on both sides of us, we were in comparatively quiet water; and on ahead was a quiet strip extending right into the darkness of the fissure in the rocks, whereas on either side of it were the foamy white rollers beating against the rocks.

There was, in fact, a huge cleft in the granite structure of the island—for I assumed that it was an island—extending down below the level of the water as well as upwards; and as the rocky bottom sloped away from the shore, this cleft furnished a safe and excellent channel through a dangerous area. In another moment we had slipped into the depths of the gorge.

It occurred to me that to a watcher from out on the sea, it would have seemed that our ship had disappeared suddenly, as though it had been swallowed up. The appearance of the island to anyone approaching as we had done, was bleak, desert, and inhospitable, the last place in the world to invite a landing. And now we were slipping down a secret passage, and were quite hidden from the outside. The whole procedure had the appearance of having been cleverly arranged to conceal whatever the island contained. My temples throbbed with excited anticipation.

Kaspar stood erect and motionless, just forward of the deckhouse, gazing ahead. I judged from his attitude that he was expecting to land soon; so I ran down into the cabin and brought up my suitcase and found as I did so, that my hands and knees were shaky from the sudden and severe strain on my nerves of the previous quarter of an hour. The sudden fright and equally sudden relief left me weak and perspiring.

The luminous rift of the sky above us began to widen; within twenty minutes, the tops of the rocky walls at the sides were low enough to be visible in the illumination of the searchlights; and the channel had widened considerably. The noise had sensibly diminished, and the speed of the ship continued to decrease. Soon the walls became irregular, interrupted by black clefts, then gradually dwindled down to scattered piles of rock. Now there was a beach, white and smooth, no doubt sand: on the left, level to the dim, dark horizon with a glow of the sea in the distance; on the right the narrow strip of bright beach shone in strong contrast with a dense, black wall, which I knew must be a forest. On ahead, a number of lights glowed brightly, from which long, glimmering streaks of reflection reached toward us. Lights meant people! Kaspar's people! In the course of a number of minutes, I was able to make out a row of brilliant lamps on poles, at the edge of a little wharf built out into the water. I scanned it eagerly with my field glasses.

I could make out a good deal of machinery on the shore, cranes and loading apparatus, and dark, irregular bulks, with wheels and cables. There was also a little group of people on the dock. I was young and impressionable enough to have gotten a thrill out of even a conventional visit to any foreign port. Imagine then, how I quivered, after my strange day on the mysterious ship, to find myself about to land on an island which was evidently off the established paths of travel, and which already was beginning to promise unusual and mysterious features.

While the ship was slowing down and slowly easing over toward the dock, I had about fifteen minutes in which to study the scene carefully. Only with the corner of my eye did I observe how two steel hoops dropped from the ship over posts on the dock, fastened to chains which spun out from the ship and then reeled back in, drawing the ship to within six or eight feet of the dock; and how the gangplank descended. I looked further on.

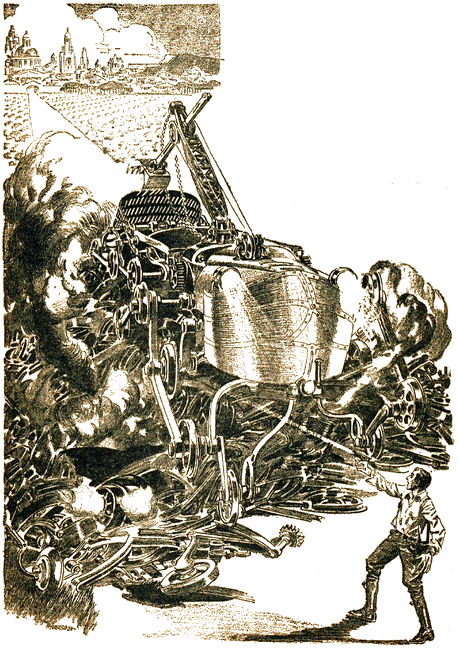

The wharf was of wooden planks, and but a little longer than the ship; evidently built for this ship only, and without facilities for permanent docking. On my left, a couple of heavy trucks were backed up toward the ship, with derricks on them, which immediately swung their hooks and cables up over the ship when the latter approached. On the shore, beyond the planking of the wharf were several other big vehicles in motion, backing into position in a row; and one emerging from the darkness beyond the limit of the lights and cutting across the lighted space. Among the big machines were scattered some very small ones; they were indefinite black blotches, and I could make out neither their structure nor their use; they merely gave the impression of being intensely active. A roar and a clatter rose from the mass of machinery; and there was a confusion of huge movement and black shadows.

Not a building of any kind was in sight anywhere. A hundred yards ahead, the intense blackness against the more luminous sky, with occasional flashes of reflection, must have been a forest. To the left, more cliffs towered in the distance.

All of the machinery was opposite the left half of the ship. A line formed by continuing the gangplank straight out from the ship, divided the illuminated territory in half, and the left half was a dense, roaring, iron bedlam; God knows what it was all about. There, at the edge nearest me, stood a towering, clumsy thing on caterpillar treads; behind it were humpbacked tractors and things with whirling wheels and gesticulating cranes.

The right half of the dock was clear and empty, except for the little group of people. On beyond them a few automobiles stood beside the road that led backward into the darkness. The people, a tiny, huddled group, looked quite incidental and subsidiary to the huge, rumbling machines.

There were about a dozen of the people, both men and women, young and old. One swift glance in the brilliant illumination told me that, and showed me that they were neatly and carefully dressed in elegant, rich-looking clothes. As we drew closer I saw at the front of the group a pretty, dark-haired girl and at her side a stately old lady with snow-white hair. Both had their heads bent backward in their effort to peer eagerly upward at the ship's deck. Then the gangplank thumped down on the dock, and Kaspar walked down without the least change in his measured tread. I picked up my suitcase and followed him; I must confess that it was a little timidly and at some distance.

I remained in the background, leaning against a lamp-post at the edge of the dock; the shadow of the lamp's base kept me in comparative obscurity. I hoped to avoid attracting undue attention to myself, at least until all the regular greetings were over. Kaspar and the majestic old lady came toward each other; first they clasped hands and leaned toward each other in a brief kiss; and then they stood for a few seconds looking into each other's eyes, hands clasped and not a word spoken. Thereupon there was a swirl of dresses and scarfs; Kaspar had a pair of little arms around his neck and a resounding kiss planted on his cheek; and then the impetuous young lady held him off at arms' length and gurgled: "Old grand-daddy's back!"

"By Jove!" I thought to myself. "I like her looks and I like her ways!"

Kaspar looked around for me, I suppose wishing to introduce me. But the others in the group were too quick for him. They crowded around him and shook hands and greeted him joyfully. It was evident that he was a beloved man. I could understand but little of what was said, because the clatter of the machinery was too loud at the point where I stood; but the expressions on their faces, clearly lighted by the lamp over my head, spoke louder than words. There was a burly, red-haired man, who might have been a building-contractor or a sea captain dressed up in society clothes, who seized Kaspar's hand with the grab of a gorilla, and whose Irish features registered such joy and relief that Kaspar's return might have meant the alleviation of all his troubles and the lightening of all his burdens. There was a slip of a young lady in a gorgeous fluffy-ruffly cloud of a dress with a marvelous head of red hair; and she approached Kaspar a little timidly and in awe, but smiled radiantly and seemed genuinely happy to see him back safe. And a young man in full evening dress of the most elegant cut and material, with perfect shirt-front and most delicately adjusted tie, approached in great respect and with the utmost perfection of social grace; but he too was happy to see Kaspar.

"Boy!" I gasped under my breath, looking at him from the top of his silk hat to the tips of his polished pumps; "to think that I came here in whipcords and laced boots, with pistols and a camp-cooking kit!"

Kaspar glanced back at me once or twice, as though apprehensive of having neglected me; but I nodded back that it was all right as far as I was concerned; and he continued to receive greetings while I watched him, giving an occasional glance at the machinery unloading the vessel. The five people whom I have already mentioned seemed to be especially close to Kaspar, for they remained at his side. They were talking animatedly together, and occasionally their voices were carried to me.

In fact, I noted that the mechanical din was lessening somewhat. Every now and then some vehicle would sweep around and disappear in the darkness, up the road. Unloading had stopped, and I surmised that only a few personal packages had been taken off, and that the ship would soon go to some more permanent berth.

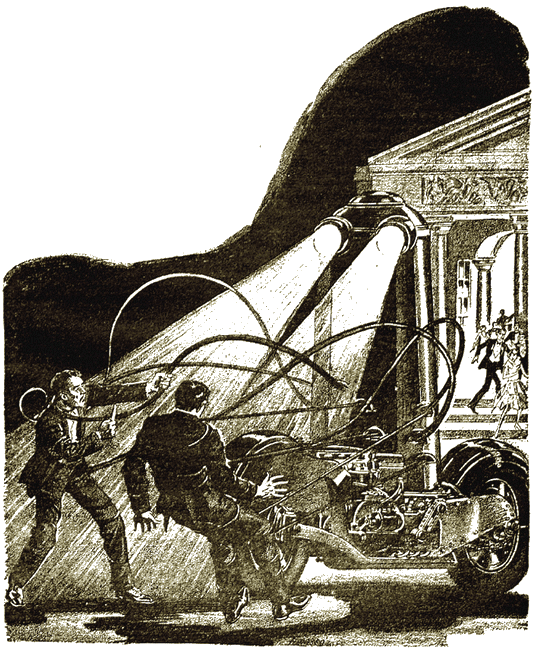

As I was watching the last crane-load swing from the deck into a truck, a most creepy looking mechanical nightmare came sputtering by with a noise like a motorcycle. It dashed by so quickly that I had no chance to observe it closely. It looked like a huge motorcycle, seven feet high, with a great, box-like body between the wheels, in which the driver must have been enclosed; and around this box were coiled many turns of black, oily-looking rope. The box was black and looked like a coffin stood on end, and rope was wound in a great coil about its upper end; and two glaring searchlights surmounted it. I don't see how anyone could imagine a more inconsistent, unnatural-looking thing.

The people talking in front of me were startled by its appearance; that was obvious. Their heads went close together, and I could see the burly Irishman slowly shaking his great red shock of hair, for all the world as though he were worried about something again. Finally Kaspar turned and motioned to me.

I came forward a few steps and approached the group. First I was presented to the white-haired old lady, who regarded me wonderingly, but spoke nothing, beyond telling me, with a manner of stately politeness, that she was pleased to make my acquaintance. In the meantime the bright-eyed girl behind her kept watching me intently, except when I was looking directly at her.

"Davy Breckenridge got aboard with me in search of adventure," Kaspar said, by way of explaining my presence; "and I could not frighten him off."

Next I found myself facing the girl. The light behind me shone directly on her; and with an opportunity to get a good look at her I found my original interest sustained and increased. In fact, I had already wasted more extra heart-beats on her than I ever had on a girl before, and I had not even exchanged a word with her. Her wide-open eyes and parted lips betrayed the curiosity and wonderment that I must have aroused in her. She seemed to be between twenty and twenty-five, and came up with an active, springy step. In contrast to the other brilliant and flouncy young lady, she wore a dress of some plain, gray-brown stuff that might have been gabardine, open at the throat, and with a skirt somewhat longer than were being worn back home just now. I could see that she was enjoying it all immensely, for her face broke out into a glowing smile as Kaspar spoke:

"Mildred, I have brought a young visitor with me, Davy Breckenridge. Davy, my granddaughter, Mildred Kaspar!"

He bowed and stepped back, with the courtly, old-fashioned way of letting the two who have been introduced occupy the center of the stage, so to speak. Uncertain as to whether an introduction in this society included the shaking of hands, I watched, but when Miss Kaspar extended hers, I took it, nothing loath.

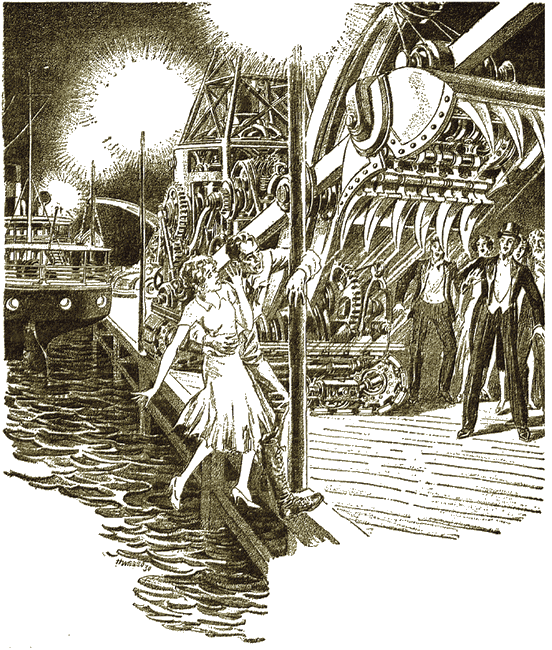

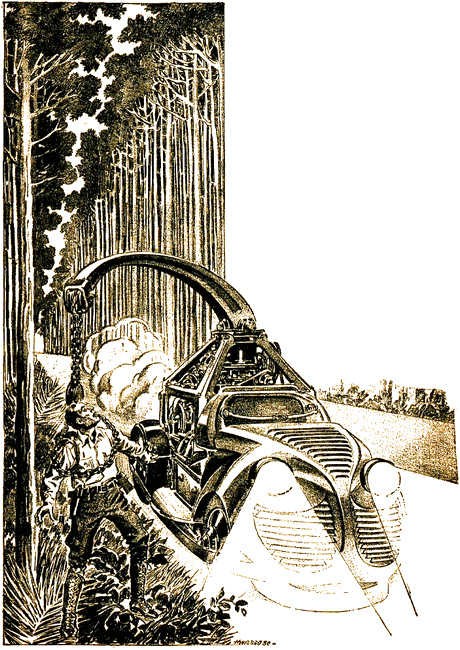

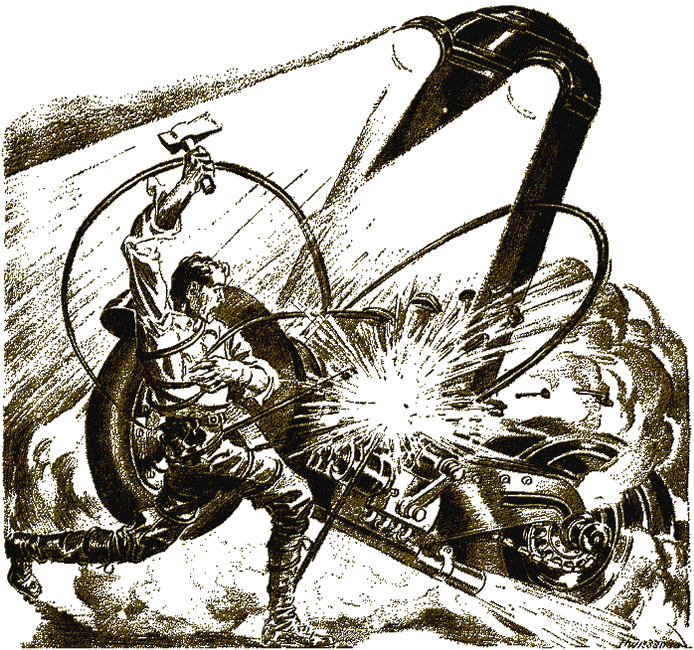

Suddenly and unexpectedly, a black shadow raced between us and there was a clank over our heads. Kaspar started, looked up, and involuntarily continued stepping back. I also looked up. A big, black crane arm was reaching over toward us from the caterpillar- treaded hulk a score of feet away. It hung high in the air, and its chain and bucket, a half ton of dirty iron just off the ground, was plunging directly at us.

There was a little scream from one of the ladies behind Kaspar, and a united scramble to get out of the thing's way. I was not in its path, I soon noted; its swing would just miss me. But Miss Kaspar, in front of me, was directly in its path; in another second it would knock her over and grind her up. For a mere instant I was paralyzed with surprise. In a moment I recollected myself, but the plunging mass was already within two feet of Miss Kaspar.

There was only one thing to do. I took a good grip on the little hand and jerked her swiftly toward me, and at the same time stepped, or rather leaped, backwards. I got a momentary glimpse of the look of amazement on her face as she was carried off her balance, but I was compelled to look behind me to keep from stepping off backwards into the water. However, I was able to guide myself to the lamp-post and back up against it; and I caught the staggering girl into my arms, for otherwise her momentum might have carried her on off the edge of the dock. It was a delicious armful; but I had no time just then to enjoy the thrill of my first experience in that line. I hastily let go and stood her on her feet, and looked for the swinging shovel. There was six feet of space to spare between us and the line of its swing. Kaspar and the three people with him stood on the opposite side of its path, motionless as though they had been suddenly petrified; and there was a straggling line of people back toward the cars, also petrified.

Miss Kaspar was looking at me with a puzzled expression on her face, but my gaze at the swinging bucket made her turn. It reached the end of its swing in a few seconds, and was coming back.

It came toward us now with a creak, over our heads, and its path was further toward the water—nearer to us. The pair of huge iron jaws was open and turned toward us; and it was coming fast.

"I wonder what's the idea?" I grumbled. "Has the fellow gone suddenly crazy?"

I had been trying to figure out, in swift flashes of thought that seemed to hang slowly in fractions of a second, whether the operator of the machine was trying to reach the pile of freight on our left, or whether he had lost control of the machine, or had parted with his wits. When Miss Kaspar saw it coming, she turned toward me with a little scream.

It came on with gathering momentum, while I was trying to figure out a way of dodging it without jumping into the water. There was no use trying to run ahead of it or to get across its path; it was moving faster than we could move. A dozen feet away were Kaspar and his people, open-mouthed, paralyzed with fear, but unable to stir to help us. I had almost made up my mind that it would have to be a plunge into the water, when I got another idea.

Without a word—there was no time for it—I seized Miss Kaspar around the waist and lifted her off her feet; I remember making a mighty effort and then being surprised at how light she felt. With my left arm around the lamp-post, I swung her and myself out over the water, bracing my feet against the edge of the dock. The bucket swung by with a rush of oily- smelling air. I breathed a sigh of relief and was about to swing her back to her feet, when she plucked at my shoulder and cried:

"Look out! It's coming again!"

"Look out! It's coming again!"

It had stopped with a clank and was swinging swiftly back. By this time the girl had begun to get heavy, and my left arm around the post, which carried the weight of both of us, was beginning to ache. She noted my efforts to ease the strain and tried to reach past me to get hold of the post.

"You can't do that," I said, "but it will help if you hang on to my neck."

She did so at once, without hesitation. I wonder that I did not lose my head and drop off into the water from sheer excitement. I was revived suddenly by a hot pain in my left arm and the sound of my sleeve tearing. The bucket had swung by again and grazed my arm. Its next swing would bring it outside the line of lamp-posts and brush us off into the water. I felt a keen appreciation for the feelings of the bound man in Poe's "Pit and the Pendulum" story.

"It's a ducking for us," I said. "Can you swim?"

She laughed.

"I'm at home in the water," she replied.

"Down we go then!"

I stopped so that she could slide down and then lent her a hand to lower her into the water; when I heard her splash I started down myself. However, the big, black shovel was so close to my head that I got frightened and let go, and fell several feet into the water. I went under for a considerable distance, but came up readily and saw Miss Kaspar clinging to a pile. I reached for my hat, which was floating near. We were between the dock and the ship, and could see nothing but the glare of the lamp above us with the blackness of the dock on one side and the hull of the ship on the other, also black as Erebus.

The gangplank was directly overhead.

"This is worse than a trap!" I exclaimed. "We've got to get out of here quick!"

I watched her anxiously until I saw her strike out easily and gracefully, apparently but little impeded by her clothes. By a natural impulse we headed toward the stern of the ship, away from the machinery. In a couple of dozen strokes we were clear of the wharf and the ship, and out in open water.

"Now, where do we go from here?" I asked, as we paused to look back. She turned around to look at me, and laughed. There was just enough light from the distant lamps so that I could see the water trickling down over her face from little wisps of hair. She was positively bewitching; the light gleamed brightly from the row of pearly teeth, and her eyes sparkled in fun. At that moment I did not know the cause of her laughter, for I was puffing hard keeping myself afloat in my heavy clothing. Later I learned that it was my tendency to lapse into the latest metropolitan idiom that had furnished the amusement. "We are safe now," she said. "Fifty yards to our left is the beach, with only a few rocks between us and the folks."

As we swam for the shore I kept my eyes on the dock; but the machine that had caused the trouble, and its crane, were not visible to me. I was thoroughly winded when we arrived at the beach, for my clothes and accoutrements were indeed a heavy load to keep on top of the water. Miss Kaspar stopped at some distance from the shore, with only her head and shoulders out of the water.

"Now you go on ahead," she ordered, with what seemed to me an overdone sternness; "and keep to your left. I shall follow you."

"What a queer code of ethics!" I exclaimed. "It's up to the hero to see that the rescued lady is safely out of the water before he gets out."

"If you don't go on, we'll be here all night. And if you dare to look back, I'll never speak to you again!" This time there was a note in her voice that sounded as though there might be tears near at hand.

"Oh what a mutt!" I groaned at myself. To her I shouted:

"All right! I'll learn after a while. It's only the first hundred years that I'm slow." Another peal of laughter behind me testified that all was well again.

The black shadows among the rocks made the way a little treacherous; but it was not long before I came suddenly out of them and to the edge of the dock. Kaspar and his three companions were at the edge of the dock where we had jumped off, looking intently down at the water; six or eight others were moving slowly back from the cars toward the water. The big, ugly machine was gone; in fact only four loaded trucks were left of the mob of machinery that had been there only a short while before. The people spoke not a word. Their rigid attitudes, their white faces and tight lips alarmed me. The big, redheaded man had his fists clenched; and in a moment he began pacing back and forth on the dock. Kaspar stood with his head bowed, looking completely crushed.

My appearance with Miss Kaspar behind me was like a thunderbolt among them. She gave them a silvery little hail. Kaspar clutched out with both hands, and his eyes stared wide open out of the snowy expanse of his beard. Mrs. Kaspar held out her arms; it seemed that it was to me, but there was a swish behind me and a shower of water and Mrs. Kaspar was holding a wriggling, wet bundle. It was hard to tell from which one of them the squeals of joy came.

The big Irishman stopped in his tracks and stared with open mouth; and the elegantly dressed young man, though struggling manfully to preserve his dignity, was showing his agitation by rubbing the back of one hand in the curved palm of the other. There was a kind of astonishment about them, as though we had risen from the dead. Only the freckle-faced young lady with the sunset hair seemed to exhibit joy unalloyed, by dancing up and down and sidewise. Kaspar laid his hand on his granddaughter's shoulder, but the embrace of the two women showed no signs of loosening. He finally turned to me and held out his hand:

"Davy, now that you have saved our baby from that awful thing, nothing can come between us."

His voice trembled, and the hand that I held trembled.

"I can't see that I did much," I answered with embarrassment. "That was a commonplace little accident—" Although in my mind, I was wondering if it really was an accident and commonplace. In the meanwhile, wraps and scarves had been requisitioned among the crowd and the two ladies had hustled Miss Kaspar away. Kaspar roused himself and again moved with that almost military air of his.

"Here are two more friends I want you to meet, Davy. This is Mr. Cassidy."

The big, red-headed man grabbed my hand with a powerful sweep. He must have been very much moved, to let a little brogue slip away from him; for never again after that did I hear him use it.

"Ye'rr a foine bhoy, an' quick an' brave," he said, from the uttermost depths of his throat. "Never in my life have I been so sick as during those few moments when our little one was in danger."

"Thank you. I don't think I've done anything."

Then came Mr. Kendall Ames, turning his head back to look after Miss Kaspar as he approached me. He seemed hardly able to pull his eyes off her. The perfection of his manner and the faultlessness of his attire combined into one harmonious effect that hushed my usual tendency to facetiousness and commanded my unadulterated admiration. Such a product on a tropical island.

Though I could detect no flaw in his perfect speech and behavior, except possibly a slight pallor and the slightest of tremors, still it seemed that he was just a little constrained and embarrassed.

"When I express to you my gratitude for your wonderful act," he said softly, in a well modulated voice, "I am merely voicing what hundreds of others will feel. You have saved our most popular lady from a terrible fate."

"I am sure that you exaggerate," was all that I was able to get out of myself.

But they were not exaggerating. Some real emotion possessed all of these people. There was something beneath the surface here. If this occurrence with the machine had been merely accident, why were they all so tense about it?

However, I did not have much time to speculate about it just then. The day had been hot; but the night was cold, and I began to shiver in my soaked clothes, and my teeth chattered. Also Kaspar discovered that my left arm was bloody. I had been holding it behind my back, until he took it and examined it. The sting of the salt water in it was making me writhe. He raised it to the light in grave concern.

"It isn't much," I said. "Just the skin scraped off. If you can find me something dry to wrap up in so that I won't shiver my joints loose, I'll have this arm dressed in a jiffy."

The three of them watched me with great interest as I opened my suitcase, took a bandage from the first-aid kit, and did a fair job of dressing with one hand.

"Bad omen!" I laughed. "The first thing I use out of my outfit is the first-aid kit."

In a moment I wished I had not said it, for over Kaspar's face came that same brooding, gloomy look that he had worn most of the afternoon on the ship.

Some robes were produced for me to put over my shoulders, apparently taken from automobiles. I was to ride in Ames' car, as Kaspar's would only hold the three of them, while Mr. Cassidy had already left with his daughter.

"That's the red-headed girl, I'll bet!" I thought to myself.

Ames was very eager, and conducted me to the car as though I had been a royal guest. I felt like the hero of a movie drama. There in the car was another young man, dressed with the same splendor as was Ames; and there followed another formal introduction. I can laugh now, but I could not then. It was all quite grave and earnest: I, soggy, bedraggled, with a bandaged arm and a blanket over my shoulders like a Choctaw chief, and feeling tremendously clumsy and out of place in all this drawing- room courtesy; and bowing to me, extending his hand, and gushing forth great volumes of gratitude was Mr. Dubois in evening dress and with manner so perfect that he would have been a model for the evening crowd at the Ritz cafe. The car had no steering wheel, and no one drove! Ames tinkered around with something on the instrument board when he got in; and in a few moments we were off.

We seemed to be running through flat, open country, over a paved road. My recollection of the early part of the ride was that it had been through dense blackness with rushing echoes about—a forest, no doubt. Now, moment after moment, more lights became visible, until there were great masses and long avenues of them.

"WHAT city is that?" I asked eagerly, forgetting my wet clothes and the cold wind. Both of the men seemed surprised at the question.

"Why—that is—our city!" Ames protested in the tone of a person making a superfluous explanation, "where we live."

"I mean, its name?" I persisted.

"Its name?" Ames seemed puzzled. "Why do you ask for a name? Walter, have you ever heard its name?"

Mr. Dubois shook his head in courteous silence.

"What island is this, then?" I asked.

"I'm afraid I do not know its 'name' either," Ames replied. He was apologetic and anxious to oblige, but helpless. "You see, we never had occasion to speak of it in such a way as to require a name."

"Where is it then?" I demanded, growing more surprised every moment.

"Where—?" he seemed totally at a loss.

"Which way and how far from Galveston? Or where in relation to Cuba or Central America?"

"I'm sorry," said Ames in a queer, embarrassed tone. "I know nothing of those places. We are all so occupied with pursuits of our own that we are not interested in what you speak of. It would serve no good purpose to go into those matters."

"You are a stranger," volunteered Dubois. "We've never had a stranger here before. It isn't considered the—ah—proper—ah—taste, you know, to show an interest outside the island."

His reply, which gave me the impression of having been spoken in the fear that someone would overhear it and make trouble for him if it wasn't properly made, silenced me for a while. They had been so cordial and sincere, until I had begun to ask questions, that I had at first gotten an impression of a high degree of culture and intelligence; and now this sudden seizure of embarrassed constraint, along with the strange limitation of their mental horizon, gave me a vague impression of mental abnormality.

Soon we were driving up a broad, paved street, lighted by rows of electric lights; and illuminated windows were visible among a wealth of black trees. Being driven about a strange city at night is always confusing.

I had impressions of meeting numerous headlights and dark vehicles; there were people fitfully revealed for a moment by moving lights, and glimpses of people upon verandas among trees. For a couple of miles there was block after block of the same thing. Finally we drove up to the curb behind another car, from which the Kaspars were alighting. Kaspar led me through an arched hedge, across a shadowy front-yard garden, into the house. The young men drove away, courteously wishing me good night, and promising to see me tomorrow.

The house astonished me. Instead of having traveled nearly a thousand miles across the Gulf of Mexico, I might merely have walked over into one of the better residence sections of Galveston or any other American city. The house was of glazed face-brick; there were mahogany furniture, electric-light fixtures, a phonograph, velvet rug, a piano. On a small drawing- room table were several books and a newspaper opened across them.

In the middle of the big living-room stood Miss Kaspar covered from head to foot with a cloak; about her head was a scarf through which showed wet spots.

Yes, she was beautiful. During my drive, I had recollected the thrilling feel of the slim body in my arms, and I feared lest my quick glance in the garish lighting of the dock had left too much to my imagination. But the tempered illumination of the room showed me the soft cheeks delicately colored with a bloom that the sea-water had not affected, the brightest of brown eyes, and the red lips that arched in a smile of welcome. As my gaze swept eagerly over her, the smile faltered, and a flush came and went. But she threw her head back with a little toss, and the smile came back, radiant as a summer sunrise, and the brown eyes looked into mine.

"I couldn't let them shoo me off to bed until I had thanked you for saving me from that horrid thing, and welcomed you to our home," she said in a soft, Southern voice, extending her hand to me. She spoke no other words, but the smile was given so generously, and the eyes met mine so frankly, that I was quite taken off my feet.

By the time I had recovered sufficiently to stutter an acknowledgment her grandmother had hurried her away.

"Horrid thing!" she had said, as though there had really been some serious danger. Obviously she was taking the incident very seriously.

"You had better go to bed too," Kaspar said to me. "After your ducking and your cold ride, you need to be careful. I must hurry to a conference with some people who are anxious to see me. Here is your room. In the morning, you will probably be up early and want to look about outdoors. Yonder is the way out to the veranda, and we shall meet you there."

I looked after the departing old man in an agony of curiosity. Would I not have the opportunity of asking a single question?

A mahogany bed, high with soft, white bedding, a chiffonier, in the corner a lavatory with hot and cold water, two brilliant landscape paintings on the wall—such was the place in which I would spend my first night on a savage and tropical island. This was the rough life for which I had prepared myself with sleeping-bag and pistols! I was reluctant to accept the realization that I was in a city that was unknown to the world and not down on the maps and in the travel books. However, no other conclusion was possible, for the cities of this region, excepting those of the American zone on the isthmus, were dreary, miserable places, not worthy of the name of city.

I awoke to see the sun shining brilliantly on a thick mass of foliage outside my window. The air that came in was cool and pleasant. As I began to move about, my arm felt sore and stiff, and was caked with dried blood. However, I dressed it afresh, and got out my razor and shaved. Ruefully I surveyed my silk shirt and cream-colored trousers; they were hopelessly unfit to appear in. There was nothing to do but to put on the laced-boots, flannel shirt, and whipcords, stiff with dried sea-salt. I knew I should feel uncomfortable and conspicuous in them among the dress-coats and delicate frocks, but no more so on account of my clothes, than on account of a sort of inferior feeling in the presence of their pretty manners and culture.

"Breakfast!" said a small placard, hung from a push button over a small, mahogany table. I was hungry enough, and the button's invitation to be pushed was irresistible. I pressed it, whereupon a panel opened in the wall, from which proceeded the sound of whirring gears; and in two or three minutes a tray appeared, on which were eggs, bacon, coffee, and rolls. It traveled toward me on a canvas belt over a revolving roller. I made short work of the food, for I was overpowered by eagerness to get outdoors and see the town by daylight. Then I eagerly made my way out on the porch and looked around. I saw a broad, paved street, lined with great masses and billows of luxuriant tropical foliage into which the houses were sunk almost out of night; here and there a fawn-colored wall, a red-tiled roof, or a row of gleaming windows peeped out of the dense verdure. Again it struck me that it might be the wealthy residence portion of any city in the south of the United States. Had the black ship gone in a circle and brought me back to Florida or Louisiana? No, that was impossible, for I had watched the course too intently during the previous day, and it had always continued southeast. Undoubtedly I was on some unknown island in the tropics; for nowhere in the United States would people talk and act so queerly as these people did. It was a rich and beautiful picture. Palms, ferns, and conifers seemed to predominate among the flora; thick, dark- green, waxy leaves and light, lacy fronds were plentiful. There were great, cream-colored flowers shaped like a jack-in-the- pulpit, as big as my head; big, scarlet hoods and spikes; white, buttercup-like flowers as big as my two hands, with purple centers.

I got out on the concrete sidewalk and started up the street on a little walk. However, before I had gone a hundred yards, I thought of the unusual appearance that my salt-crusted, rough- looking clothes presented in such an elegant residence section, and my timidity drove me back toward Kaspar's house. Just before I reached it, at the gate of the neighboring house, there was a flutter of white, and there stood the freckle-faced, Titian- haired young lady of yesterday evening.

"Ooooh!" she exclaimed. "Good morning! You surprised me!"

"Good morning," I replied, trying to be as courtly as I had seen Ames and Dubois act, but feeling silly at it "You are Miss Cassidy?"

"I am Phyllis—Phyllis Cassidy. How is Mildred?" she looked toward the house.

"I haven't seen her this morning, but she looked all right to me last night."

I chuckled to myself at having unconsciously stated what I so warmly felt; for Miss Kaspar certainly looked all right to me the night before.

"Come, I'll go over with you. That was perfectly grand of you to save her!" she gurgled ecstatically. "I've read about brave things like that and seen them on the stage—but to think that I should ever see it real—and to talk to a man who dared to do such a thing!"

She drew a deep breath of delight. "And everyone was terribly frightened that awful things would happen."

"You have a beautiful city here," I interrupted, for I was getting embarrassed. "What is its name?"

"Its name!" Her flow of words stopped in surprise. "The name of the city? I do not know if it has a name. Sometimes we say: 'The City of Beauty.'"

"And what island is this?"

"What island? You want a name for the island too? You queer man. Why should it have a name? It's just 'the Island.' It is very large, and I've never seen all of it and shouldn't want to see all of it. There are woods and mountains and ugly black and oily places—"

"Where is this island?" It may have seen rude to interrupt, but otherwise no progress was possible. I could see that she had vast possibilities as a rapid-fire conversationalist.

"Where? Why here! Where could it be?—But father warned me that you might talk like this, and so I'm not shocked. You are a stranger. We do not discuss things about the island. It is not nice. There are so many other things. I've just had a big tapestry hung at the Artist's Annual; you know tapestry design is my serious work. That made my father very proud. And see this little medal? That is the swimming honor for the Magnolia District, and this is the second year that I've held it—"

About there I sank in the deluge of words; but she prattled on. Finally, I figured out something with which to interrupt again, wondering, however, how long she could keep it up if she were not interrupted.

"You have some rather amazing machinery here," I remarked. "I should like to see more of it."

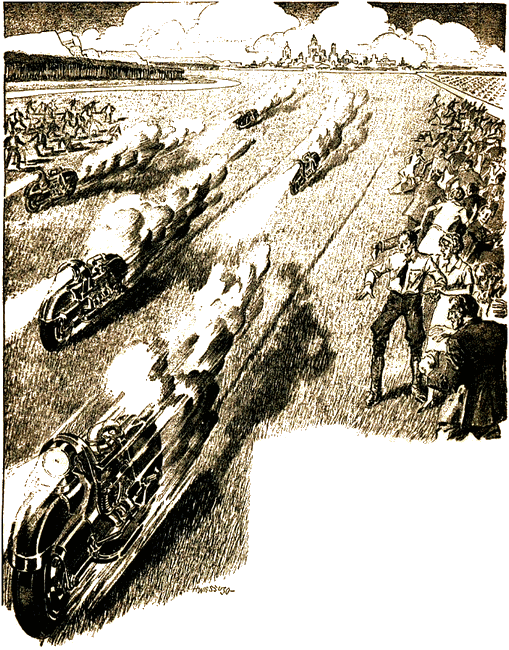

Her delighted expression faded instantly, and she shuddered. "Machines are disgusting things," she said, curling up her little freckled nose. "We do not talk about them. But I'm not shocked at you. Daddy told me not to be, because you do not understand the island. Just think how lucky you are, coming today. This afternoon is the Hopo championship ride. I am so excited about it, because I know Kendall Ames will win it."

A rapt expression came into her face, and she clapped her transparent white hands childishly.

"You're going, aren't you?" she asked eagerly.

We turned into Kaspar's gate, and there on the porch was Miss Kaspar. And at once I lost interest in Phyllis and Hopo, whatever that was.

"I suppose," I replied mechanically, my eyes on the figure of Miss Kaspar standing on the porch.

"Oh, you must!" She put her hand on my sleeve and started off on another long flood of talk. My conception of courtesy compelled me to stand there listening, with her hand on my arm, and groan inwardly while Miss Kaspar turned and walked into the house, disappearing from my sight without a word to me. If it all looked as I felt, it must have been a ridiculous picture. I wished Phyllis at the bottom of the sea. Her childish prattle had kept me from seeing Miss Kaspar again. She followed Miss Kaspar into the house, and I wandered disconsolately about the yard. I thought that it was very strange that Miss Kaspar had not spoken to me; in fact she had acted as though she had not seen me at all.

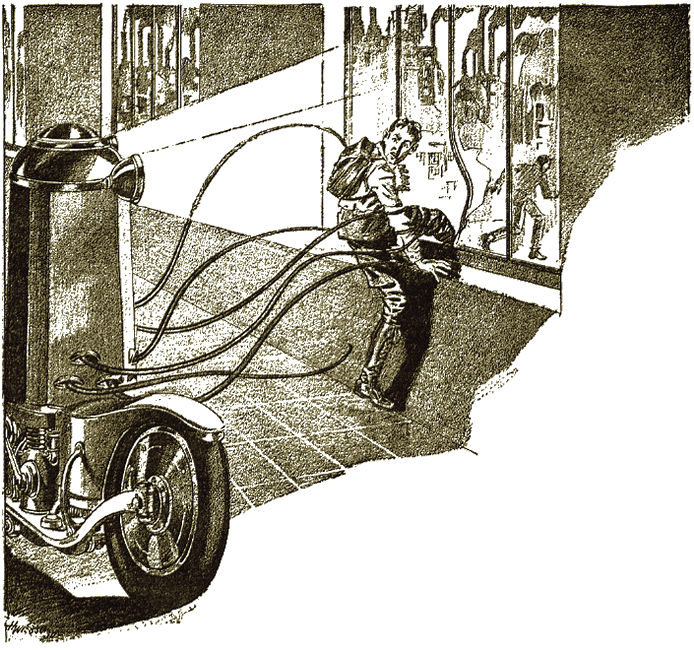

I spent most of the forenoon wandering about the yard and through the house. I wondered what had become of everyone, and why I had been thus left to my own resources. I found the house a mixture of the commonplace and the marvelous. Familiar, ordinary furniture, such as I have already mentioned contrasted with the automatic cooking going on in the kitchen by means of timing- clocks and thermostats and without human attention. The "house- cleaning" device was especially interesting to me.

I was attracted to the drawing-room by a humming noise; it came from a black enameled affair like an electric motor, just beneath the ceiling. It was moving slowly about the ceiling, dragging something through the room after it; and as I watched I noted that it was covering the room systematically by means of a sort of "traveling-crane" arrangement. The things hanging from the motor were light hoses with expanded endings, and the surprising thing about them was that they moved and curled about this way and that, like an elephant's trunk or a cat's tail. They reached here and there, poked into corners, under chairs, and around objects; and I could hear the sound of the suction as their vacuum cleaned up the dust. When the room had all been cleaned, the apparatus receded into an opening in the wall, and hid out of sight.

"If this is the way they keep house," I thought, "I can understand how they can raise such flowers as Phyllis for tapestry design and swimming championships."

It was nearly noon when Ames appeared, clad in a gorgeous scarlet jockey uniform, with shiny boots and golden spurs, and in his arms a great bouquet of flowers. I was in a distant corner of the lawn, and watched him as he stood bowing to Miss Kaspar, who appeared in response to his knock.

"I trust that my fair lady of Magnolia Manor is enjoying good health," he said with pompous graciousness. "I am on my way to the Hopo field, and if you will accept this token from me and wear one of the flowers, I know it will bring me victory."

I could not hear her reply, but I could see that she thanked him formally. Then Ames saw me and came over to me.

"If you have no afternoon suit with you," he said looking me over, "you are welcome to one of mine. You and I are of about a size. I'll send one over."

I had to admit that it was considerate of him to think of it. But I felt resentful because I had to accept a favor from him; for what was I to judge from what I had seen, except that there must be some intimate relationship between him and Miss Kaspar?

"Lunch is ready!" Miss Kaspar called to me in a voice that sounded coldly polite; and she did not seem to notice me as I came in. No one waited on the table at luncheon, at which the four of us sat. Everything was on the table when we sat down, and we left the things there when we were through; and the next time I glanced at the table they were gone, removed, doubtless, by some mechanism. I had already seen enough to be convinced that the servant problem did not exist on the island. The only servants were machines.

"Ha! ha!" laughed Miss Kaspar, but would not meet my eyes. "I see that you have spent a pleasant morning. Phyllis is a jolly little girl, isn't she?"

I was taken aback. Where was the Miss Kaspar who had given me her hand the evening before? She looked just as lovely as ever; but she had no eyes for me at all, and that engaging cordiality and frankness that had impressed me far more than her beauty were gone. But then, who was I, to expect to be noticed by her, when Ames had brought her a bale of flowers as big as herself? My sphere had always been action and not women; a horse on the range, or doing something in a laboratory were familiar to me; but with women I was clumsy and incompetent. The present reminder of that fact was the most unpleasant one I had ever had. Ames seemed to be the real hero among the ladies; and Miss Kaspar was obviously the fortunate lady.

Just then there was a click and a rush of air at one side of the room. A panel snapped open and a package dropped out; and the panel clapped loudly shut again.

"Clothes for you from Kendall Ames," Kaspar announced. "I imagine this is something new to you. Ames puts them into a tube at his home; they go to a central distributing station which sends them here."

I went resignedly into my room to put on the clothes. The interest seemed to have been taken out of things for me. But I intended to go with them to their Hopo, or whatever it was; at least I should have an opportunity to see more of the people of the island. When I came out again, there were several young people on the porch, and more of them in a large car at the curb. They were ready to go to the scene of the sport, and had come to take Miss Kaspar with them.

They were interesting folks. The young men wore dark coats and light trousers, and were very courtly in speech and manner, quite in contrast with the direct and forward manners of the youth that I had been accustomed to. The girls wore light, fluffy dresses in pale shades of blue, orange, yellow, and pink; and they were full of smiles and curtsies and little feminine ways that charmed me very much. I confess I preferred them to the blunt and callow ways of our modern girls.

Amazement surged up in me again. Here I had set out for a tropical island, expecting to find jungle and savagery; at most some squalid mixture of Indian and Iberian. Yet, here was a freshness and delicacy of human culture, a flower of human beauty, a development of the fine things in human looks and manners, of which I had never seen the like in the most favored urban circumstances that I had ever known.

The young people sat for a moment and chatted trivialities; while some who had remained in the car played on a guitar-like instrument and sang. Their voices were well trained and their playing was clear and soft. They seemed in every way clean and beautiful young people; and with the deep-green lined street, the bright houses and brilliant flowers, it all seemed rather like a dream of beauty.

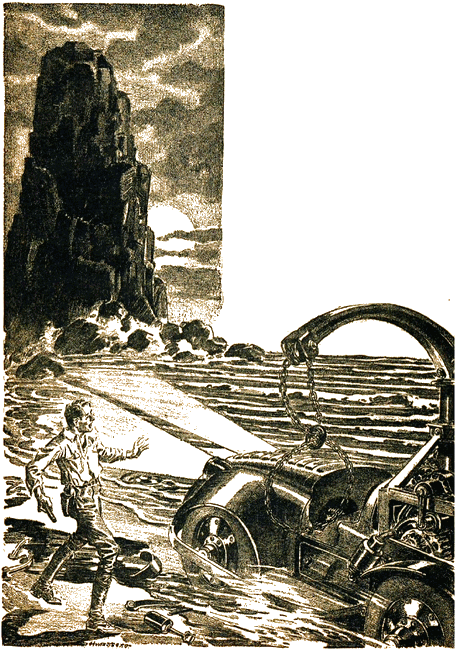

"I'll get out Sappho for your first," Miss Kaspar cried to her grandfather; and the affectionate glow that lighted up her sunny face, as she glanced at him, caused a pang within me for being left out of things. I had to remind myself that last night's rescue did not necessarily give me any special rights nor privileges; and that I ought to be thankful for the kindness that had been bestowed upon me last night. She hurried out of the back door; and "Sappho" turned out to be a greenish-black roadster, with wheels four feet high, an extraordinarily large radiator appropriate to hot climates, headlights set in the top of the hood—and no steering wheel! The machine fascinated me so that I stood about it curiously instead of mixing with the group of young people.

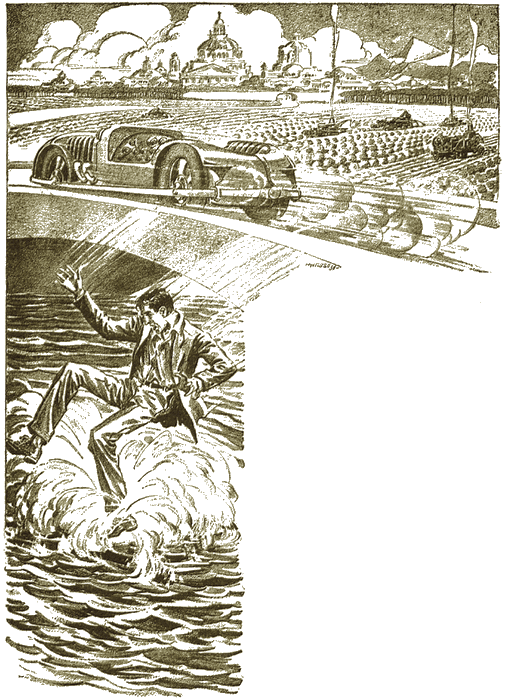

In fact, I was a little nettled at the people. They seemed to take no particular nor unusual interest in me. Upon introduction they were very gracious; but they immediately took me for granted as one of them. No one asked me where I came from, nor what my country was like, nor how I liked it here. Like a group of frolicking children, they seemed intent on the interests of the moment, and accepted everything as it came. So, I decided to ride with Kaspar in his Sappho.

I waited for some minutes for Kaspar to appear. Then I walked all around the curious vehicle, and I finally decided to get into the car and wait there for Kaspar. So I climbed in and sat down, with a queer feeling at the complete absence of the steering wheel and gearshift levers. However, on the dashboard were a great many dials; and something was ticking quietly somewhere inside the machine. Then there was a "clickety-click" and a whirr of the motor, and the car moved gently away from the curb. It swerved out into the street, gathered speed, and then turned to the right around a corner. It slowed down for two women crossing the street, and avoided a truck coming toward us. It gave me an eerie feeling to sit in the thing and have it carry me around automatically.

Then it suddenly dawned on me, that here I was alone in the thing, on an unknown street, in an unknown city, racing along at too high a speed to jump out, and rapidly getting farther away from places with which I was familiar. How could the machine be controlled? Already I was completely lost in the city. How and why had the thing started? I had been exceptionally careful not to touch anything, and was sure that no act of mine had set it off. But I was rather proud that I did not lose my head; I leaned back to think. This was not my first emergency.

The car was carrying me rapidly through a beautiful residence section of the city. I could not help looking about me. It was a veritable Garden of Eden, and all the more beautiful for the added touch of human art. The lawns were smooth and soft, with half-disclosed statuary among the shrubbery, or fountains at the end of vistas. Homes spread over the ground or soared into the air like realized dreams, without regard to expense or material limitations. But, every few minutes my mind came back with a jerk to my own anomalous position. I examined the dials on the instrument-board closely. There were ten of them, and they had knobs like the dials on a safe-door, or like the tuning dials on a radio receiving set. Some of them had letters around the periphery and others had figures. I looked for something that said "stop" or "start," but there was nothing of the sort, nor even any words of any kind. There were a number of meters, but a speedometer was the only one whose use I recognized. The whole proposition looked about as impossible to me as a Chinese puzzle.

The more I thought about it, the more I thought that my only hope was to try manipulating the dials. That was the only way to learn something about managing the car. I did so: I twirled a knob at random and waited expectantly. Nothing happened. At least not immediately. After a few moments, however, the car stopped, turned around, and started off in the opposite direction. I should have gotten out of it while it stood still for an instant; but for the moment my curiosity was whetted, and I wanted to try the dials again to see what would happen. Anyway, before I recollected myself, the car was speeding in the opposite direction at too rapid a rate to permit my getting off.

If I had hoped to get back to Kaspar's this way, I was disappointed at the first corner, where the car turned to the right, drove around a block and was soon spinning along in its original direction.

"You're a stubborn jade, Sappho," I grumbled aloud. "We'll have to see what we can do with you."

I now perceived where I had made my mistake: I had not noted which dial I had turned nor how I had turned it, when I had reversed the car, and I was unable to repeat the movement. So, the next time, I carefully turned the first dial to the letter "A". There was no effect at all. I moved the second dial to "A". A curious fluty whistling followed; it proceeded from the hood, and varied up and down several octaves of the musical scale, with a remote resemblance to rhythm and melody. Before it died down, I sank back and gave up. A little refection showed me that with ten dials and twenty-five letters or figures to a dial, there were several million combinations. It was hopeless. For a moment the scenery distracted me again. I was bowling along comfortably, and did not seem in any particular danger.

The buildings I was passing seemed to have grown in response to a creative artistic impulse just as luxuriantly and as untrammeled as the dense tropical vegetation among which they stood. Dream palaces they seemed, with colonnades and sweeping arches and marble carvings gleaming in the sun.

Such a city could be possible only by means of vast wealth, highly advanced culture, and unlimited leisure on the part of the inhabitants. Where did the wealth come from? I could not see any place where any business was being transacted nor any industry going on, although my ride covered every section of the city that afternoon. I did pass through a small and quiet shopping district; but here there was no display, and its purpose was evidently not that of selling and making money, but rather that of supplying needs and desires.

Gradually an uncomfortable feeling began to get the best of me. In vain my reason told me that there was no real danger, and that I was having a good time. I felt hopelessly at the mercy of the machine, and I did not like it. I began to yield to an unreasoning panic; it made me think of how my hunting-dog had behaved the first time I had tried to give him a ride in an automobile.