RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Amazing Stories, December 1928, with "The Appendix and the Spectacles"

Our well-known author treats us to a different sort of Fourth Dimensional story here. Incidentally, it's a very clever psychological study—one which will leave you chuckling. And you may well wonder, if the Fourth Dimension is exploited, whether we will have situations such as the one so well told in this tale.

OLD CLADGETT, President of the First National Bank of Collegeburg, scowled across the mahogany table at the miserable young man. He was all hunched up into great rolls and hanging pouches, and he scowled till the room grew gloomy and the ceiling seemed to lower. "I'm running a bank, not a charity club," he growled, planting his fist on the table.

Bookstrom winced, and then controlled himself with a little shiver.

"But sir," he protested, "all I ask for is an extension of time on this note. I could easily pay it out in three or four years. If you force me to pay it now, I shall have to give up my medical course."

Harsh, inchoate, guttural noises issued from Cladgett's throat.

"This bank isn't looking after little boys and their dreams," he snarled. "This note is due and you pay it. You're able-bodied and can work."

Mechanically, as in a daze, Bookstrom took out a wallet and counted out the money. When the sum was complete, he had ten dollars left. The hope that had spurred him on through several years of hardship and difficulty, the hope of graduating as a physician and having a practice of his own, now was gone. He was at the end of his resources. Once the medical course was interrupted, he knew there was no hope of getting back to it. Nowadays the study of medicine is too strenuous; there is no dallying on the path to an M.D. degree.

He went straight over to the University to apply for an instructorship in Applied Mathematics that had recently been offered to him. In the movies and in the novels, an ogre like Cladgett usually meets with some kind of retribution before long. The Black Hand gets him or a wronged debtor poisons him, or a brick house collapses on his head. But Cladgett lived along in Collegeburg, growing more and more prosperous. He was bound to grow wealthy, because he took all he could get from everybody and never gave anybody anything. He kept growing a little grayer and a little fatter, and seemed to derive more and more pleasure and happiness from preying financially on his fellow-beings. And he seemed as safe as the Rock of Gibraltar.

THEN, after fifteen years, a sudden attack of acute

appendicitis got him. That morning he had sat at his desk and

dictated letters to his directors commanding them to be present

at a meeting four days hence without fail. The bank was taking

over a big estate as trustee, and unless each director signed the

contract personally, the deal was lost and with it a fat fee. In

the afternoon he was in bed groaning with pain and cursing the

doctor for not curing him at once.

"Appendicitis!" he shrieked. "Impossible!"

Dr. Banza bowed and said nothing. With delicate fingertips he felt of the muscles in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen. He shook his head over the thermometer that he took out of the sick man's mouth. He withdrew a drop of blood from the patient's finger-tip into a tiny pipette and took it away with him.

He was back in an hour, and Cladgett read the verdict in his face.

"Operation!" he yowled like a whipped boy. "I can't have an operation! I'll die!"

He seemed to consider it the doctor's fault that he had appendicitis and would have to have an operation. "Say," he said more rationally, as an idea occurred to him. "Do you realize that I've got an important directors' meeting in three days? I can't miss that for any operation. Now listen; be sensible. I'll give you a thousand dollars if you get me to that meeting in good shape."

Dr. Banza shrugged his shoulders.

"I'm going to dinner now," he said in the voice that one uses to a peevish child. "You have two or three hours in which to think it over. By that time I'm afraid you will be an emergency."

Dr. Banza sauntered thoughtfully over to the College Tavern, and walking in, looked around for a table at which to eat his dinner. He felt his shoulder touched.

"Sit down and eat with me," invited his unnoticed friend.

"Why, hello Bookstrom!" he cried warmly, as he perceived who it was.

"Hello yourself," returned Bookstrom, now portly and cheerful enough, with a little twinkle in each eye.

"But what's the matter? You look dark and discouraged."

So, over the dinner, Banza told his friend about the annoying dilemma with the obdurate and irascible Cladgett, who threatened certain ruin to his career.

"I feel like telling him to go to hell," Dr. Banza concluded.

Bookstrom sat a long time in silent thought, his elbows leaned on the table, sizzling a little tune through his cupped hands.

"Just the thing I've been looking for," he said at last slowly, as though he had come to a difficult decision. "Do you want to listen to a little lecture, Banza? Then you can decide whether I can help you or not?"

"If you can help me, you're some medicine-man. Shoot the lecture, though." Dr. Banza leaned back and waited, with much outward show of patience.

"You remember," opened Bookstrom, "that I had a couple of years of medical college work, and had to quit. That accounts for my having gotten this idea so suddenly just now.

"My present title of Professor of Applied Mathematics is not an empty one. I've applied some mathematics this time, I'll tell the world.

"You hear a lot about the Fourth Dimension nowadays. Most people snort when you mention it. Some point a finger at you or grab your coat lapel, and ask you what it is. I don't know what it is! Don't get to imagining that I've discovered what the fourth dimension is. But, I don't know what light is, or what gravitation is, except in a 'pure mathematics' sense. Yet, I utilize light and gravitation in a practical way every day, do I not?

"Well, I've learned how to utilize the fourth dimension without knowing what it is. And here's how we can apply it to your Cladgett. Only, I've got an ancient grudge against that bird, and he's got to pay me back in real money for it, right now. You take your thousand and get a thousand for me—.

"Now, how can we use the fourth dimension to help him? In order to explain it, I'll have to illustrate with an example from a two-dimensional plane of existence. Suppose you and Cladgett were two-dimensional beings confined to the plane of this sheet of paper. You could move about in any direction upon the paper, but you could not get upwards off of it. Here is Cladgett. You can go all around him, but you can't jump over him, any more than you can turn yourself inside out.

"The only way that you, a two-dimensional surgeon can remove an appendix from this two-dimensional wretch, is to make a hole somewhere in his circumference, reach in, separate the doojigger from its attachments and pull it out, all limited to the surface of the paper. Is that plain so far?"

Banza nodded without interrupting.

"But, suppose some Professor of Applied Mathematics arranges it so that you can rise slightly, infinitely slightly above the plane of the paper. Then you can get Cladgett's appendix out without making any break in his circumference. All you do is to get up above him, locate your appendix, and reach down or lower yourself down to the original plane, and whisk out the appendix.

"He, being confined to the two-dimensional plane of the paper, cannot see how you do it, or comprehend how. But here you are, back down to the plane of the paper again beside Cladgett, with the appendix in your hand, and he marvels how you did it."

"Brilliant reasoning," Dr. Banza admitted. "But unfortunately for its value in this emergency, Cladgett is a three-dimensional old hulk and so am I."

"To proceed," Bookstrom made a show of ignoring the interruption, "suppose I had constructed an elevator that could lift you a little, ever so little along the fourth dimension, at right angles to the other three. Then you could reach over and hook out Cladgett's appendix without making any abdominal wound."

Bookstrom stopped and smiled. Banza jumped to his feet.

"Well, dammit, have you?" he demanded. People in the Tavern were turning around and looking at them.

"Come and see!"

THEY hooked arms and went up to Bookstrom's laboratory.

Apparently Banza was satisfied with what he saw, for in five

minutes he came racing out of the door, and called a taxi and had

himself whirled to Cladgett's house.

There he had some trouble about the two thousand dollars in advance. It was an unethical thing to demand, but he was a clever enough psychologist to sense and respect Bookstrom's reasons.

"I've found a specialist," he announced, "and am personally convinced that he can do what you want. With the next two days quiet in bed and subsequent care in diet, you can get to the meeting."

"Go ahead then," moaned Cladgett.

"But this man wants a thousand dollars, and insists that his thousand and mine must both be paid in advance," said Banza meekly.

Cladgett rose up in bed.

"Oh, you doctors are a bunch of robbers!" he shouted. Then he groaned and fell back again. The appendicitis was too much for him. A pain as sustained and long-enduring as that of an acute appendicitis will compel anyone to do anything. Soon Cladgett and a nurse were in an ambulance speeding toward the University, and Banza had two checks in his pocket.

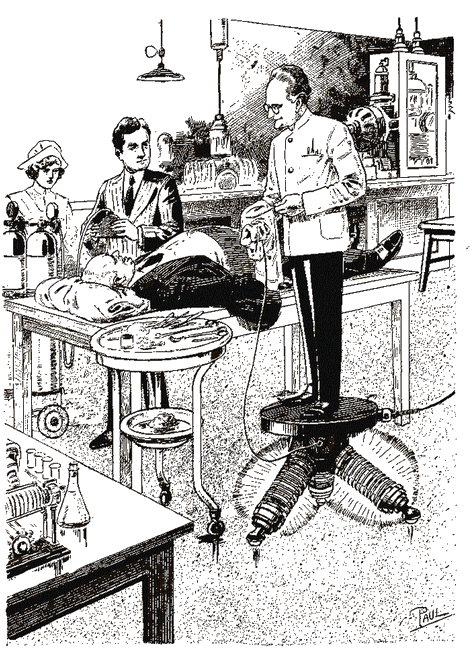

Bookstrom was all ready. A half dozen simple surgical instruments to suffice for actually detaching the appendix, were sterilized and covered. He put Cladgett on a long wooden table and asked the nurse to sit at his head with a chloroform mask, with orders to use it if he complained. He directed Banza to scrub his hands. Beside Cladgett was the "elevator."

There wasn't much to the machine. All great things are simple, I suppose. There were three trussed beams of aluminum at right angles to each other, each with a cylinder and plunger, and from them, toggles coming together at a point where there was a sort of "universal joint" topped by a mat of thick rubber. That was all.

"You mean for me to get on that thing and be shoved somewhere into nowhere—?" Banza looked worried.

"I won't insist," Bookstrom smiled.

"No thanks," Banza backed away with alacrity. "I'll give him whatever anesthetic he needs." Banza was no doubt uncomfortable with responsibility, for the patient was seriously ill.

"Fine!" Bookstrom seemed to be enjoying the situation thoroughly. "I still know how to whack off an appendix. That's elementary surgery, amateur stuff."

A storm of protest broke from Cladgett.

"I don't want to be operated. You promised—"; he wrung his hands and beat his heels upon the table.

"We promised," said Bookstrom sweetly, "that we would not open you up. You'll never find a scratch on yourself."

Cladgett quieted down. Bookstrom scrubbed his hands, and wrapped his right one in a sterile towel in order to manipulate the machine. He stepped on the rubber mat, and in a moment, Dr. Banza and the nurse were amazed to see him click suddenly out of sight.

Cladgett quieted down. Bookstrom scrubbed his hands,

and wrapped his right one in a sterile towel in order to

manipulate the machine. He stepped on the rubber mat...

Click! and he was not there! Before they recovered from their astonishment, Cladgett began to complain. Dr. Banza had to start giving chloroform. He gave it slowly and cautiously, while Cladgett groaned and cursed and threshed himself about.

"Lie still, you fool!" shouted Bookstrom's voice in a preoccupied way, just beside them. It made their flesh creep, for he was not there. Gradually the patient quieted down and breathed deeply and the doctor and the nurse took a breath of relief, and had time to wonder about everything. There was another click! and there stood Bookstrom with a tray of bloody instruments in his hand.

"Pippin!" he exclaimed enthusiastically, pointing to the appendix.

It was swollen to the size of a thumb, with purple blotches of congestion, black areas of gangrene, and yellow patches of fibrin. "You're not such a bad diagnostician, Banza!"

"Put it in formalin—to show him how sick he was," suggested Banza.

"You'll have a fat time proving to anybody that that was taken out of him. Forget it, and deposit your check. Some day when you get up your nerve, let me show you how it feels to see the inside of a man, all at once, everything working."

Cladgett was much better the next day. His pain was all gone and he did not feel the terrible, prostrating sickness of the day before. As soon as he awoke he felt himself all over for an operation wound, and finding none, mumbled to himself surlily for a while. The second day his fever was gone and he was ravenously hungry. On the third day he was merely tired. On the fourth day he went to the directors' meeting in his own car, grumbling that he had never had any appendicitis anyhow, and that the doctors had defrauded him of two thousand dollars.

"Got a notion to sue you for damages. May do it yet!" he snarled at Dr. Banza. "I'll include the value of my spectacles. You smashed them for me somewhere. Damn carelessness."

Dr. Banza bowed himself out.

"The next time he needs a doctor," he said to himself, "he can call one from Madagascar before I'll go to see him."

But Dr. Banza was no different from any other good physician. It wasn't two weeks before Cladgett called him, and again he was "fool enough to go," as he himself expressed it.

This time Cladgett was not in bed. He was nursing his hemispherical abdomen in an arm-chair.

"Thought you said you'd cure me of this appendicitis!" he wheezed antagonistically.

"Aha, so you did have appendicitis?" thought the doctor to himself.

Aloud, he asked Cladgett to describe his symptoms, which Cladgett did in the popular way.

"I think it's adhesions!" he snapped.

"Adhesions exist chiefly in the brains of the laity, and in the conversation of doctors too lazy to make a diagnosis." Dr. Banza's courteous patience was deserting him.

He temperatured and pulsed his patient, gently palpated the abdominal muscles, and counted the leucocytes in a drop of blood.

"You do have a tender spot," he mused; "and possibly a slight palpable mass. But no signs of any infectious process. No muscle rigidity. Is it getting worse?"

"Getting worse every day!" he groaned histrionically. "What is it, doc?"

Dr. Banza resisted heroically the temptation to tell him that he had carcinoma of the ovary, and said instead with studied care: "I can't be quite sure till we have an X-ray. Can you come down to the office?"

With much grunting and wheezing, Cladgett got up to the office and up on the radiographic table. Dr. Banza made a trial exposure and then several other films. He remained in the developing room for an interminable length of time, and then came out with a red face.

"Well! What?" yapped Cladgett.

"Oh, just a trifling matter of no importance. Come, get into the car with me. We'll drive over to Professor Bookstrom's laboratory, and in a moment we'll have you permanently relieved and feeling good."

"I'll not go to that charlatan again!" roared Cladgett. "And you doctors are always trying to talk all around the bush and refusing to tell people the truth. You can't work that gag on me! I want to know exactly!"

He shook both arms at Banza.

"Why, really!" Dr. Banza acted very much embarrassed. "It's nothing that cannot be corrected in a few seconds—"

"Dammit!" shrieked Cladgett. "Gimme that X-ray picture, or I'll smash up your place!"

Dr. Banza went in and got the wet film clipped in its frame. He led the way to the outside door. Cladgett angrily followed him thither and there received the film. Banza backed away, while Cladgett held the negative up to the light. There, very plainly visible in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen was a pair of old-fashioned pince-nez spectacles!

Strange heavings and tremors seemed to traverse Cladgett's bulk, showing through his clothes. He shook and undulated and heaved suddenly in spots. His face turned alternately white and purple; his jaw worked up and down, and his mouth opened and shut convulsively, though no sound came forth. Suddenly he turned and stamped out of the building, carrying the wet film with him.

The old man was a pretty good judge of character, or he never would have made the money he did. In some subconscious way he had realized that Bookstrom must be the man to see about this thing. Banza telephoned Bookstrom at once and told him the details.

"How unfortunate!" Bookstrom exclaimed. There was a suspicious note in his voice. That solicitude for Cladgett could hardly have been genuine.

"He's coming over there!" warned Banza.

"I shall be proud to receive such a distinguished guest."

That was all Banza was able to accomplish. He was sick with consternation and anxiety.

Bookstrom could hear Cladgett's thunderous approach down the hall. Then the door burst open and a chair went down, followed by a rack of charts and a tall case full of models. Cladgett seemed to derive some satisfaction from the havoc, this time little dreaming that Bookstrom was quite capable of setting the stage for just such a show.

"You—you—" sputtered Cladgett, still unable to speak coherently.

"Too bad; too bad," consoled Bookstrom kindly. "Let's see your roentgenogram."

"Ah, how interesting!" Bookstrom could put vast enthusiasm into his voice. "The question is, I suppose, how they got in there?" He looked back and forth from Cladgett's protruding hemisphere to the spectacles on the X-ray film, as if to imply that in such an immense vault there surely ought to be room for such a trifling thing as a pair of spectacles.

"You put them there, you crook, you scoundrel, you robber, you dirty thief!" The "dirty thief" came out in a high falsetto shriek.

"You do me much honor," Bookstrom bowed. "That would be a 'stunt' I might say, to be proud of."

"You don't deny it, do you?" Cladgett suddenly calmed down and spoke in acidly triumphant tones.

"It strikes me," Bookstrom mused, "that this is something that would be difficult either to prove or to deny."

"I've got the goods on you." Cladgett spoke coldly, just as he had on that occasion fifteen years before. "You either pay me fifty thousand dollars damages, or this goes to court at once."

"My dear Sir!" Bookstrom bowed gravely. "You or anyone else have a standing invitation to go through my effects, and if you find more than a hundred dollars, you are welcome to half of it, if you give me the other half."

Cladgett did not know how to reply to this.

"I'm suing you for damages at once!" His words came like blows from a pile-driver.

Bookstrom bowed him out with a smile.

THE damage suit created considerable flare in the headlines. A

pair of spectacles left in a patient's abdomen at operation! That

was a morsel such as the public had not had to scandalize over

for some time! Newspapers dug up the details, even to the history

of the forced payment on the note fifteen years before and the

disappointed medical student; and the fact that the operation had

been performed in secret and at night, in the laboratory of a man

who was not a licensed medical practitioner, for Bookstrom's

title of "doctor" was a philosophical, not a medical one. The

public gloated and licked its chops in anticipation of more

morsels at the trial.

But no such treat ever came off. Immediately after the suit was filed Bookstrom's counsel requested permission to examine thoroughly the person of the plaintiff. This was granted. The counsel then quietly and privately called the judge's attention to the fact that the plaintiff's body contained no scars or marks of operation of any kind; therefore, it was evident that he had never been operated upon and, therefore, nothing could have been left in his abdomen. The judge held an informal preliminary hearing and threw the case out of court. He admitted that there were curious phases to it, but he was busy and tired, and his docket was so full that it made him nervous; he was glad to forget anything that was technically settled.

Cladgett continued to grow sicker. The pain and the lump in his side increased. In another two weeks he was a miserable man. He still managed to be up and about a little, but his face was drawn from suffering (and rage), and pains racked him constantly. He had lost twenty-five pounds in weight, and looked like a wretched shadow of his former self.

One day he thrust himself into Bookstrom's office. Bookstrom dismissed the stenographer and the two student-assistants, and faced Cladgett blandly.

"Banza says you can fix this up somehow," he said, and it sounded like "gr-r-rump, gr-r-r-ump, gr-r-rump!"

"I've decided to let you go ahead."

"Very kind of you," Bookstrom purred. "I ought to feel humbly grateful for as big a favor as that. As a matter of fact, I've decided to let the Sultan of Sulu go jump in the lake. But I've a lurking suspicion that he isn't going to do it."

Cladgett sat and stared at him awhile, and then picked himself up and stumped out, grumbling and groaning.

The next day Dr. Banza brought him into Dr. Bookstrom's laboratory.

He eased himself down into a chair before saying anything.

"I'm convinced that Banza's right and that you can help me. Now what's your robber's price?"

"It's a highway robber's price, with the accent on the high," murmured Bookstrom deprecatingly.

"Well, out with it, you—" there Cladgett wisely checked himself.

"I ask nothing whatever for myself," said Bookstrom, suddenly becoming serious. "But if you want me to get those spectacles out of you, right here and now you settle a sum to found a Students' Fund to loan money to worthy and needy scientific students, which they may pay back when they are established and earning money. I think when you spoke to me about a damage suit you mentioned the sum of fifty thousand dollars. Let's call it that."

"Fifty thousand dollars!" screamed Cladgett in a high falsetto. He was weak and unstable. "That's preposterous! That's criminal extortion."

"This transaction is not of my seeking," Bookstrom suggested.

"You've fixed it all up on me," Cladgett wailed, but his voice sank toward the end.

"Tell that to the judge. Or, go to a surgeon and have him open you up and take them out. That would come cheaper."

"Operation!" shrieked Cladgett. "I can't stand an operation."

He looked desperately at Banza, but there was no hope there.

"This seems to me a wonderful opportunity," Banza said, "for you to do a public service and distinguish yourself in the community. I'm sure that amount of money will not affect you seriously."

Cladgett started for the door, and then groaned and fell back heavily into his chair. He sat groaning for awhile, his suffering being mental as well as physical; finally he reached into his pocket for his pen and his checkbook. He kept on groaning as he wrote out a check and flung it on the table.

"Now, damn you, help me!" he yelped.

They put him on the table.

"Banza, you scrub. You deserve to see this," directed Bookstrom.

So Banza stepped on the rubber mat and Bookstrom instructed him.

"Move this switch one button at a time. That will always raise you a notch. Look around each time until you get it just right."

With the first click Banza disappeared, just as people vanish suddenly in the movies. Cladgett groaned and squirmed and then was quiet. With another click Banza appeared, and in his hand was a pair of old-fashioned pince-nez spectacles, moist and covered with a grayish film. He held them toward Cladgett, who grabbed them and mumbled something.

"Can you imagine!" breathed Banza, "standing in the center of a sphere and seeing all the abdominal organs around you at once? Something like that, it seemed; not exactly either. There above my head were the coils of the small intestine. To the right was the caecum with the spectacles beside it; to my left the sigmoid and the muscles; attached to the ilium, and beneath my feet the peritoneum of the anterior abdominal wall. But, I was terribly dizzy for some reason; I could not stand it very long, much as I should have liked to remain inside of him for awhile—"

"But, you weren't inside of him," corrected Bookstrom.

Banza stared blankly.

"But, I've just told you. There I was inside of him, with his viscera all around me, stomach and diaphragm in front, bladder behind—I was inside of him."

"Yes, it looked that way to you," nodded Bookstrom. "That is the way your brain, accustomed to three-dimensional space, interpreted it. But look. If I draw a circle on this sheet of paper, I can see all points on the inside of it, can I not? Yet, if you were a two-dimensional being, I would have a hard time convincing you that I am not inside the circle."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.