RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

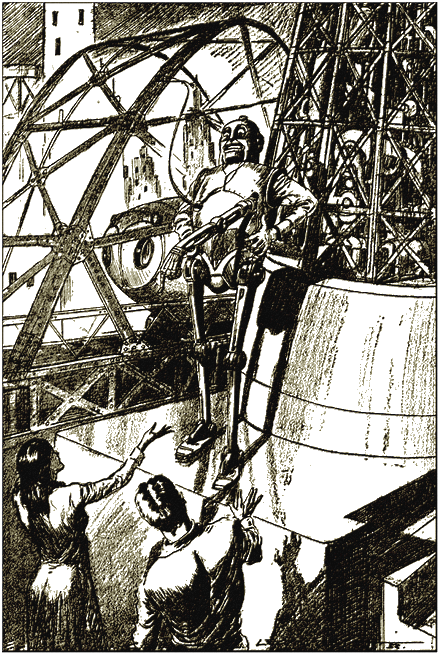

Amazing Stories, December 1933, with "The Strength of the Weak"

Petrescu, with the afternoon sunlight glinting on his

polished metal, stood on a platform beside the tower.

Dr. Breuer, an eminent diagnostician and among our favourite authors, gives us one of his science-fiction stories—fiction because of the narration but with true science in it. He tells us about the little understood synapse and give besides a very exciting drama of life and passion.

AT the girl's first shriek, Professor Worcester rushed into the main laboratory, out of the door which led from his little cubby-hole of an office. He was a short little sliver of a man, with a small bald head and large spectacles.

"Why, Marko!" he exclaimed, and his breath seemed to leave him at what he saw. "Why! You?"

Then he suddenly straightened up, and became dignified even in his tininess.

"Take your hands off my daughter! At once!"

Marko Petrescu laughed. It was absurd. He could continue to hold the beautiful and struggling Helen Louis by one hand, and brush away the Professor with the other, without any trouble. He was huge and powerful, even beside an average, well-built man.

At the laugh, Professor Worcester reached in his pocket, drew out and opened a penknife, with a thin blade, three inches long. With this he rushed at the powerful man who was crushing his struggling daughter in two big arms. Petrescu saw the blade. Swiftly he tightened the grasp of one arm on the girl's body till she screamed, and freed the other. With the free hand he clouted the onrushing Professor on the side of the head. The poor little man of science sank to the floor with a weak groan, his spectacles sliding several feet along the smooth tiling.

Petrescu lifted the girl off the floor, bundled her under his arm, with one hand across her mouth, and hastened out of the place. He hurried across the corridor toward the back door, near which his car was parked. He grinned and chuckled to himself; all the exultation of the primeval male, drunk with violence and women's beauty, was his. But fortune intervened.

It appeared first in the form of a ton or two of something hard and swift, that landed without warning on Petrescu's chin. A straw hat clattered to the floor, and over it, the young, red-headed fellow, whose tan suit quite failed to conceal his football build, reached toward Helen Louise. As the black-haired, would-be captor began to sag in the knees, the newcomer picked up Helen Louise and stood her up facing him.

"Jerry!" she cried joyously, and in a moment sprang about his neck.

"Movie stuff?" asked Jerry sarcastically, prodding the big bulk on the floor with his foot. "What you up to, fellow?"

"My father!" Helen Louise suddenly recollected. "He's hurt!"

She drew her rescuer by the hand back into the laboratory. Professor Worcester was not hurt much. He was sitting up on the floor when they came in, with one hand to his head. As they appeared, he closed up his penknife and put it in his pocket. Slowly, with many small contortions, he rose to his feet.

"Tell us about it, Helen Louise," he said, still staggering a little from his vertigo. "Tell us about it," echoed Jerry.

"Well," Helen began, "a while ago Marko Petrescu slapped his notebook shut, covered up his microscope, and put away his boxes of slides. 'I'm done,' he said, quietly enough, but his voice was frightening. There was a terrible turmoil under its quietness.

"I kept on working at my microtome, cutting sections of father's neuroma. Something about him frightened me.

"'I've got it!' he said, and the exultation in his voice made the room tremble. 'And with it will come wealth, power, whatever I want.'"

"What is it that he's got, so big?" Jerry inquired.

"He's been working," the Professor replied, "on the nature of the synapse: how does the imponderable nervous impulse jump across the empty space that separates two nerves which are known to communicate with each other? The synapse, you know, is a mystery to all physiologists. Everyone here in the White Neuropathological Foundation has had a try at it. Understanding it would mean understanding how thought moves matter; for there in the synapse is where thought, an immaterial thing, gets hold and controls our material muscles and bones.

"If Petrescu has really found that, he can do anything, all the way from devising new, more efficient and more pleasant anesthetics, to freeing mind from matter or putting new matter under the control of mind!"

"Boy!" sighed Jerry. "What a feature that would make in the Sunday issue! If I could have only got that from him before I socked him."

Jerry, true to the reporter's instinct, ran out into the hall. But the huge form of Petrescu had disappeared.

"Go on," they both said to Helen Louise.

"Oh, that is all. He wanted me to marry him, and run away with him at once. He made the wildest promises of power and wealth. He's crazy."

"And then he tried to make love to you by force, eh? And your game old dad tried to interfere? Well, good thing I just got a notion I wanted to see your sweet face about this time."

"Wait till he comes back, to-morrow," the Professor said.

PETRESCU did not come back to-morrow, nor ever again. His private effects had evidently been previously removed from the laboratory. In a few days they gave him up and put another graduate student in his department of the research laboratory.

"From now on," Professor Worcester said, shaking his small fist, "it will be my job in the world to teach that man a lesson. There are things in the world besides brute strength."

Professor Worcester did not dream how true this would turn out to be some day; though it would be many years.

FOR things went along for several years, and nothing more was ever heard of Petrescu anywhere in the scientific world nor in the world of common men. He simply disappeared. Jerry and Helen Louise had plans to be married, but many things kept interfering with them. Professor Worcester was writing a book on tumors, and for nearly a year Helen Louise was so indispensable to him in the laboratory that she hesitated to mention to him marriage with Jerry, even though the Professor liked Jerry. Then Jerry was sent to Shanghai as special correspondent for his paper, where he remained for four months. During all this time he kept up a steady and frequent correspondence with Helen Louise, and in fact received a letter from her on the day he started back for New York.

When he arrived, he sent his baggage to his own rooms, and took a taxi to the Neuropathological Foundation. He found it in consternation. That very day, Helen Louise Worcester had disappeared!

Her father remembered hearing her go into her bedroom the night before. She did not appear in the morning, and he thought it rather strange, but went on down to the laboratory. He spent an anxious forenoon, and, when by noon there was no sign of her, he informed the police that he was suspicious, for it had been her habit for years to do as she pleased, but to inform her father of her every movement merely because she respected his anxiety about her. Jerry arrived at 4:30 P.M., and nothing had been heard of her.

Nothing was ever heard of her. To pack all of the frantic searching of police, private detectives and newspaper reporters, the desperate offers of reward for information, the numbing, heart-rending ache of waiting, day after day, week after week, the gradual settling down to dumb, hopeless, despairing resignation, all into a sentence, is difficult. But it must be done, for that is not part of our story. The only thing about it, that concerns us, is that both Jerry and Professor Worcester were positive that Marko Petrescu's hand had shown right through it.

AFTER a year of searching, using all the odd sources of information available to a reporter, Jerry had found his anguish keen as ever. Perhaps people forget, thought Jerry, but he didn't believe it. Baffled as he was, he clenched his fists every night and vowed to find her. In order that he might do this, he first of all realized that he must keep his first-class physical condition constantly up to par; and he forced himself to remain in training, like the splendid athlete he had always been. His editor, sympathizing with his sorrow, kept him as busy as possible, feeling that was the best service he could render.

Professor Worcester was different. His research lost impetus, and he would be seen going about the laboratory and talking to himself. More frequently than anything else, he would be mumbling to himself:

"It is the desire of my life to teach that scoundrel a lesson!"

Very mildly put, one might say. Yet these mild people are sometimes the most to be feared.

Then, suddenly, one day, the Professor vanished. In the morning his house-keeper, hired after Helen Louise's disappearance, waited for him impatiently for breakfast, went up to his room, and found that his bed had not been slept in. Telephone calls to the laboratory disclosed that he had left the previous evening as usual. The case was dumped into the lap of the police by the Foundation authorities and by the housekeeper. Only Jerry reserved to himself the right to do some digging on his own account.

"That fellow is behind all of this. No doubt of that. How to get some kind of a start at the problem—" he worried to himself.

He had serious talks with his friend the managing editor, and this shrewd man saw the hopelessness of the quest, and as a result, worked Jerry harder than ever, for Jerry's own good.

Time did not pass rapidly for Jerry, and the few weeks seemed a hundred years before he received the strange letter. He brought it to his managing editor. It was in one of the European type of envelopes with a flowered paper lining, and had an Algerian postage stamp. It contained a small portion of kid leather, recognizable as having been cut from Helen Louise's glove.

"If you want to see Miss Worcester," it said succinctly, "follow the green plane from the Azores on July 9th, 4 o'clock A.M."

"Suppose it were a trap?" the editor suggested.

"Well, supposing it is! They've got her, and I'm getting at the bottom of it. I've got a week to make the date."

The editor said nothing but wondered if he were losing a valuable reporter.

Jerry duly awaited the coming of 4 o'clock A.M. at the Azores landing field. Precisely on the second, a plane appeared from the east, and turned out to be a bright green when it came near enough. As Jerry rose in his plane, the green plane circled and started back eastward. Jerry was a good navigator, and he started out to keep careful track of the course on which the green plane led him. Subsequently the correctness of his observations was confirmed. The green plane led him to Sarah Ann Island, the island which was on the charts of a century ago, and which no one has been able to find.

NO matter how fast Jerry flew, the green plane kept ahead of him, so that he could barely keep it in sight. When they "hove to" over the island, the plane dove down, and by the time Jerry arrived, no plane was to be seen, though at the southern end, near a clump of buildings, there was an excellent landing-field.

Jerry was cautious. He did not feel like plunging down abruptly to a landing. He slowed down and circled about the island. It contained only about a dozen square miles, most of which was dense jungle. Above the middle of this, his engine went dead. No effort could start it again.

"You're wrong," Jerry muttered. By proper maneuvering, he could readily land on the landing-field. "I'll be damned if I do, and you can't make me." Jerry was convinced that outside interference had stopped his magneto, with the idea of forcing him down.

He selected a particularly woolly portion of the jungle, and gradually settled down on it. With a great crashing of small limbs, the plane eventually caught. He jumped, after convincing himself that the damage done to the plane was largely superficial, and with patience, could be repaired.

As he clambered ponderously down the tall tree, with canteen and pistol and emergency-ration bag, he heard a crashing through the brush below, and in a moment a ring of unkempt-looking human beings had gathered clamoringly around the base of the tree. They were tattered, grimy, bearded and emaciated; and they seemed enraged at him. He caught fragments of English words.

Jerry desisted from his downward progress. Their upraised claws and shaken fists did not spell cordial welcome. No one of them looked very formidable; they looked weak and ill-fed. But there were too many for safety. Jerry clung, and pondered what to do next.

"Who are you?" Jerry shouted. "What do you want with me?"

The ragged mob suddenly broke into a new uproar of terrific clamor. Sticks and chunks of dirt flew around Jerry's ears. But he could make nothing out of their answers.

Suddenly a cry rang out! A woman's cry, half scream of alarm, half shout of delight.

"Jerry!" cried a little brown figure running out of the brush. It was Helen Louise in khaki and much tanned. "Let him alone! He's my friend."

The mob stood a moment in surprise. In another, Jerry had leaped to the ground; and as Jerry and Helen Louise stood there locked tightly in each other's arms for minute after minute, the ragged people slunk away, one by one.

When they had held each other off at arm's length and again hugged tightly and kissed alternately, and asked repeatedly how are you, and are you well, finally they settled down to hear each other's stories.

"They thought you were Petrescu," Helen Louise said. "They will not bother you any more."

In fact, just then two of them came running up, offering Jerry a number of bananas with some incoherent words he did not understand.

"Petrescu is a demon," she continued. "He had me shut up in his house a while—oh, no; he treated me quite kindly. But I got away.

"Here is what he is doing. You remember, he discovered the secret of the synapse, the threshold where the intangible thought impulse is transformed into the tangible current in the material nerve-fiber. For following up his discovery, he had to come here; it involved investigation that could not be carried out in a civilized country. He tortured hundreds of people before he learned how to get a thought out as an electric current on a wire; and probably vice versa, to make thoughts by means of electric currents in wires. He showed me human brains out on the laboratory table with wires running from them, moving needles and lighting bulbs.

"He has a luxurious residence and a wonderful laboratory, and a whole town of machinery to wait on him. And all of the machines have human brains in them, to keep them running."

Helen Louise wept softly for a moment. Jerry held her tightly and waited patiently for her to go on.

"My father," she moaned softly. Then she braced up and went on. "He had my father laid out on the laboratory table, and promised him his liberty if—if he, Petrescu, could— could have me—If not, he would put father's brain in a machine.

"Now my father's brain is in a big tower full of machinery that stands at one end of the town and it switches rails and lifts bridges and opens gates.

"His body is gone. I don't know what he does with the bodies. I don't know if father is dead or not. I don't know if my father is the tower, or is a body somewhere without a brain—.

"And Petrescu gloated over my humiliation because my father is in charge of all the machinery that serves his wants. Just a sort of butler or janitor on a large scale, Petrescu said. Those brains are his slaves. They cannot work their own will; they must serve his. 'Your father had a good brain,' Petrescu said to me; 'he could have done better things. But he opposed me.'"

"But," Jerry said, his breath shocked out of him by the horrors he had heard from the lips of this beautiful girl, "such a sacrifice! I could not ever expect you to sacrifice your father that way, just to remain loyal to me."

She clung to him.

"Jerry, you don't understand yet. Petrescu is not a human being. He has made a machine of himself. Only his brain is flesh. The rest is machinery."

"And he wants you!" Jerry clenched his fists. "A monster of iron! What—why—. But how did you get away? And who are these people?"

"They are people he has brought here and couldn't use, or doesn't need yet. They know he can come and get them whenever he wants them; each one expects him to come for them sometime. He does want them, one by one.

"He had me in his house, and it is a beautiful place. He tried to be good to me, but I hated and feared him. He is just an ugly bunch of machinery; he hurt and bruised me no matter how gently he tried to touch me.

"One day when he was gone, I wandered all over the house. There were several machines about with human brains in them. I could expect no help from them; they were all under the absolute control of Petrescu and carried out his wishes only. I peeped into the laboratory. A body lay on the table. I became frightened and fled anywhere my feet would carry me. I waited by a door till a machine went through, and followed, and waited by a gate till night. I waited by the bridge till it went down for some machines coming in from the jungle, and I got through in the dark. I have lived with the people here. But my every moment is filled with terror, because I know he will come and get me."

Jerry held her quietly in his arms for long minutes, or they may have been hours.

"There are enough people here to help me repair that plane and get her away," kept going through his brain. "Then I could bring help and rescue them."

She went off with the women to sleep in caves. He went with men, but hardly saw them. His head was full of plans. Late into the night he lay awake figuring the details of repairing the plane.

TOWARD morning, some women came shrieking into the men's area. The monster had been among them. He had crashed through the jungle, breaking down all obstacles with his iron body. His brilliant light had flashed among them, and rested upon the beautiful one. He had seized her and crashed back into the jungle with her.

Jerry was frantic. He paced about, but realized the folly of pursuit. All he could do would be to get lost in the jungle at night. Eventually he sat down and planned. He had all his directions. He knew where the group of buildings lay, on a delta-shaped island between the two mouths of a river. He started at sunrise, filling up with water, and eating bananas as he walked.

He reached the river, and saw its two bridges, one across each branch. He saw the big, rambling house of concrete, with many additions and accretions, irregular and jumbled looking. He saw the many accessory buildings, all of concrete, shops, chimneys, sheds, huge doors, all arranged on three or four streets. Huge bars shut off access to the raised bridges. At the point of the delta, between the two bridges which diverged like a "Y," stood the tower full of machinery. In that tower, controlling it was Professor Worcester's brain, at the beck and call of Petrescu's every whim. Poor old Professor Worcester! The tower had a sort of wizened, melancholy look against the huge buildings behind it.

Getting across the river was a small matter for Jerry. Keeping out of sight, he fashioned a small raft to float his clothes, pistol, canteen, and food, and swam over. Scattered rocks afforded places of concealment for dressing and observation.

The big concrete residence of Petrescu looked like a medieval castle. It was surrounded by walls, within which were beautiful gardens of flowers, ornamental trees, and shrubbery. There were a dozen other concrete buildings of various sizes, but all square and unadorned, and arranged along three or four streets. Nowhere were there any people, but vehicles and various kinds of machines on wheels went back and forth. There was a bright shiny one of delicate glass and nickel and spinning things; there was a big, lumbering tub-like thing with large geared wheels. There was no one in them. They went out of one building, up the street, and into another, all apparently going about their own purposes. Of course. They had human brains in them!

For a long time Jerry lay hidden. It did not seem safe to venture out. There was no place on the bare streets for concealment; and there seemed no particular objective for him—unless it was the big, rambling concrete house. Then he saw Petrescu. He knew at once that it was Petrescu that stalked out of the house; seven feet high, topped by some kind of a big helmet with goggle eyes and screened holes and several antennae—Jerry surmised at once that this metal skull contained accessory brains and intensified special senses. There were two natural arms coming out of the metal barrel-like torso, and two grotesque ones; one snaky, metallic, coiling like a rat's tail, with a fine, little spidery hand at the end of it; the other a skeleton-like thing of steel rods with complicated gears at the joints, with a big, complex, jointed hand at the end. The legs were more like this last arm, powerful steel rods and gears.

This monster, which Jerry felt instinctively was the same Petrescu he had known on the Neuropathological laboratory, stopped for a moment outside the door and looked about suspiciously. Jerry sank down behind his rock.

At the next look, Jerry saw him striding down the street. He walked up to the tower and spoke to it in a harsh voice. Machinery started up in a near by building in a few moments. In another building, doors opened wide. In a third, a row of bright, blue mercury-vapor lights sprang up. The little village seemed suddenly to become active, as a result of Petrescu's harsh command to the control tower, which housed Professor Worcester's brain. How it must have humiliated the Professor, Jerry thought, to have absolute control over a thousand things a day, to keep the village going, and yet to be compelled to be a slave to Petrescu's every whim, even to keeping his own daughter a prisoner!

PETRESCU strode back and entered the building in which the Cooper-Hewitt lights glowed. Jerry gave him a half hour's time, and then slipped around behind the building and peeped in through the lower corner of a window. Within he saw the monster working at a table; in front of him were stacks of papers, glowing tubes, glasses and metal things, too many and too complicated to understand. His two natural hands were busy with small mechanical devices.

Jerry turned and ran. With the aid of a tree, he was over the wall in a moment. He ran through the gardens without giving their exotic beauty a glance. He found the door yielding to his pressure, and plunged in. He found himself in a luxurious corridor, with beautiful rooms opening off it. A queer little machine came scurrying down toward him. He was about to ignore it when it suddenly occurred to him that these things had brains. He caught one of the baby carriage wheels and looked the vehicle over. It had a flat top with an everted edge like a tray, and six flexible arms. Underneath there were some complicated things. Jerry spoke to it:

"Can you talk?"

There was no reply,

"Will you try to report me or raise an alarm?"

No sign from the machine. But down the hall there came a harsh voice:

"I'll report you, after I lay you out." It was a tall apparatus, erect and somewhat human, and carried a duster.

Jerry had his pistol out and in a flash had it covered.

"Stop!" he shouted.

It stopped. Obviously, it understood pistols. Obviously it feared them.

"Who are you?" the machine demanded roughly. "What do you want in here? Have you not been given to understand that no one is allowed here but the Master?"

"The girl is here!" Jerry answered and asked at the same time.

"Yes. The girl is the Master's!"

Jerry ground his teeth. The machine started forward.

"Stop!" roared Jerry.

"You have a human brain," Jerry began. "Do you remember when you were human, what love was like? This girl is mine. She and I love each other. The Master has no right to her, and she loathes him."

A harsh, cackling laugh came from the machine.

"I remember once having those silly sentiments. They are quite useless in real life. Most impractical. You ought to have the Master put your brain into a machine."

"Is that what he wants to do with her?" Jerry gasped.

"No," the machine grated. "He is keeping her human—for himself."

"But—" Jerry was puzzled. "That can't be. She is mine. Remember, you yourself once—"

"No use," the machine said more gently. "Even if I were sorry for you, I couldn't disobey the Master. He made all machines to serve his will. We follow only his wish. We are made that way."

"Well, I'm sorry," Jerry said, and shot the machine in the head. The roar of the shot, the loud clink of the bullet into the metal, the whirring of things inside, the toppling crash of the thing on the floor, made an exciting succession of sounds.

When it quieted down, Jerry heard faint shrieks coming from somewhere far within the house. He hurried on through mazes of halls and rooms, calling loudly to Helen Louise. Presently the shrieks stopped.

"Where are you?" Jerry shouted.

She came down the hall toward him, and they flew to each other's arms.

"What are they doing to you?" Jerry asked, stroking her hair and looking down at her.

"I'm all right," she answered pluckily.

"I wondered what the shooting and banging was about."

"I had to shoot the butler back there."

"That was poor old Jervis' brain. He was once a lawyer, though not a very good one." Helen Louise seemed to be sorry at the demise of the machine and its human brain.

"Let's get out of here," Jerry suggested.

Helen Louise looked doubtful. But she came along as he hurried her down corridors towards the outer door.

"Are there others in the house who might stop us?" Jerry asked.

"Oh yes. Or worse, they can let him know."

"Then hurry."

They found the door locked.

Jerry kicked out a window, and both landed on the lawn, breathless.

"Looks bad," Jerry muttered. "They must be onto us, if they locked the door."

He took her hand and they ran swiftly across the lawn toward the nearest shrubbery.

They were too late. Petrescu came striding noisily into the gate from the street. He stopped at the locked door, and saw the broken window. By this time, Jerry and Helen Louise had hidden behind thick leaves. Petrescu stood still a while, and looked around.

They could hear him cackle harshly, and his muttered words came to them:

"Well, he's saved me the trouble of going out and getting him. I need his brain; it ought to be good."

Jerry aimed carefully at his head, and shot. Plainly they could see the splatter of the dull lead on the shiny helmet. The second shot splattered over the shiny barrel of a body right over the heart area. But Petrescu never even minded the impact of the bullets. He started promptly toward the source of the shooting, with another harsh, inarticulate cackle.

He found them unerringly, and seized Jerry with the snaky arm.

"Run!" shouted Jerry to Helen Louise, and she unthinkingly obeyed, running swiftly away.

Jerry still had his gun in his hand, and it was instinctive for him to apply its muzzle to the twitching coil that was holding him, and pull the trigger. His shot severed it, and the distal portion fell to the ground, emitting small blue sparks. Jerry jumped, brushing past the other arms that grasped at him. His shot had surprised Petrescu sufficiently to get himself a start.

He caught up with Helen Louise, gripped her hand and dragged her along behind him. They tumbled over the wall, staggered among the rocks, gained the river's edge, and lay panting behind the rocks. They suddenly realized that Petrescu had not followed them.

"Of course not," Jerry said. "That is a too common and obvious thing to expect from him—to chase us. He will have more subtle ways of getting at us."

It was not long before they heard a loud, mechanically amplified voice blaring out:

"You had best show yourselves. You can't get away. If you do not come at once, I shall raze everything flat on this island till I find you. It will then be the last act of my existence to tear you slowly to pieces before each other's eyes!"

"Well!" Jerry observed, almost gleefully. "The old chap's somewhat human after all. He's jealous!"

"He'll do it, though," the girl said, pale with terror. "He is capable of things like that."

"I'll give you ten," the voice blared, and began to count:

"One—two—three—four..."

Helen Louise begged Jerry to give up.

"Think you'll fare any better if we do?" Jerry asked, drawing her toward the water. "We can swim across, and stand an even chance with him in the jungle."

"Eight—nine—"

"Here we are!"

Helen Louise had lost her nerve; she had sprung up on her feet and shrieked. "Come and take us!"

"Too late!" the voice blared. "I have counted ten. Now, I'll destroy the island and all the brains on it. Then I'll slowly pull an arm off the girl and then off the man. I'll give them a few minutes, and pull a leg first off one and then the other. Then one tongue out after the other. That ought to give me two or three hours of enjoyment."

"Come on Jerry." Helen Louise now took turn drawing him after her. "There he is ahead of us, going the other way, not noticing us at all."

They followed him around the corner of the wall, and down the street. He looked back and laughed as they emerged.

"I gave you a great man's love, and your spurned it," he bellowed back at the girl. "You fooled me once too often."

He strode on toward the control tower.

"Stop!" shrieked Helen Louise again. "We give up."

"I don't want you now. It is too late. This—" sweeping one of his natural arms around—"was all for you. Now, one word to your learned father's brain here, and the whole village will be a wreck. And then my sweet revenge."

Petrescu walked more and more slowly, while the two lovers ran behind him. They had come quite near him, and Helen Louise's head sank and she had no more breath left. Now he was barely across the little street from them, at the foot of the tower.

Petrescu, with the afternoon sunlight glinting on his polished metal, stood on a platform beside the tower. At this close distance, Jerry could see that the tower was but a mass of wheels and levers and moving rods and revolving parts; a busy machine. And there, just behind it, it seemed only a couple of leaps away, were the bridges, ten seconds between them and the jungle. But the heavy iron beams swung across the bridge entrances, and between them and the water was Petrescu and his steel arm.

"Well, Professor Worcester,"—the metallic voice had a sarcastic ring to it—"soon we'll both be done with this existence, which is neither life nor death and has no purpose. But, to you and the others, this existence is pleasanter than nothing. For you, my dear Professor, I've saved a nice little treat. First smash the village, and then watch me amuse myself with your daughter and her lover."

Again his harsh laugh rang out, and he continued:

"I shall count three. When I say three! set up your third, seventh and eleventh series of vibrations. They will shake everything down into small pieces, except a circle fifty feet in radius around you, which will include us. Take a last look at your buildings. Get set! One, two, three!"

Jerry and Helen Louise paled, and felt an icy pang of horror through them. They clung to each other and looked about aghast. Their eyes darted about the village in apprehension at the catastrophe.

But, nothing happened.

Petrescu was also surprised. A hoarse mumbling came from his helmet.

Then a tremor began in the machinery of the tower. There was a vibration as though an unbalanced wheel were revolving at high speed. There were gradually added, one by one, gratings, squeakings, each second becoming more hideous, as though there were a terrible conflict raging between the various parts of the machinery. The two young people's teeth were on edge from the sounds.

Their eyes were suddenly attracted to one of the huge iron bars that hung across the street, blocking the bridge. It had twitched. Now it rose swiftly as a shot, high in the air. Down it came, gathering momentum till it hummed through the air.

With terrific momentum the huge weight of iron crashed right down on Petrescu's head! There lay the beam of steel at the foot of the tower, and the mixture of human body and metal parts that was crushed and crumpled under it, was all that was left of Petrescu, a flat, sticky mass of debris.

For a moment they could not realize that he was really gone.

Then they had to watch the tower. The machinery was much quieter. Through it came vague sounds that seemed like attempts at an articulate voice. It seemed like words, but they could make out nothing.

Helen Louise burst into tears.

"It is father, trying to speak!"

Jerry could think of nothing to do but to hold her quietly in his arms.

"And I cannot understand him. And it sounds like suffering."

Suddenly a crack appeared down the middle of the tower. Fragments broke and toppled down. In an amazingly few seconds, nothing was left of the tower but a pile of crumpled dust. From the village there came a hum. All the walls seemed to tremble and melt. As they looked at it, the island became a flat surface, upon which were scattered numerous low mounds of dust; except that at one end there was a garden of lovely flowers and variegated trees.

"Poor little Professor," Jerry said, as Helen Louise sobbed on his arm. "He did his little 'job in the world,' didn't he?"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.