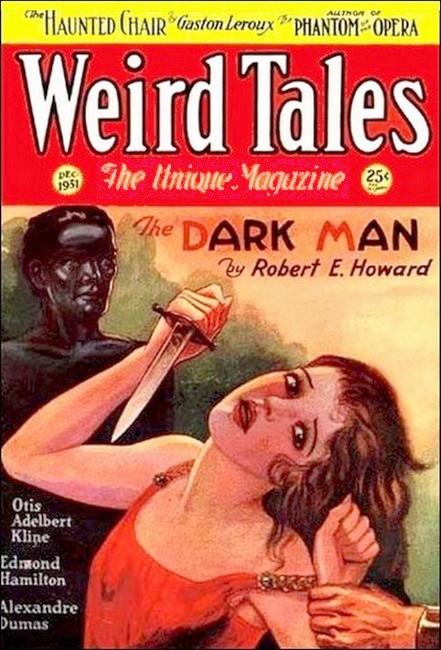

Weird Tales, December 1931

"For this is the night of the drawing of

swords,

And the painted tower of the heathen hordes

Leans to our hammers, fires and cords,

Leans a little and falls."

— Chesterton

A BITING wind drifted the snow as it fell. The surf snarled along the rugged shore and farther out the long leaden combers moaned ceaselessly. Through the gray dawn that was stealing over the coast of Connacht a fisherman came trudging, a man rugged as the land that bore him. His feet were wrapped in rough cured leather; a single garment of deerskin scantily outlined his body. He wore no other clothing. As he strode stolidly along the shore, as heedless of the bitter cold as if he were the shaggy beast he appeared at first glance, he halted. Another man loomed up out of the veil of falling snow and drifting sea-mist. Turlogh Dubh stood before him.

This man was nearly a head taller than the stocky fisherman, and he had the bearing of a fighting man. No single glance would suffice, but any man or woman whose eyes fell on Turlogh Dubh would look long. Six feet and one inch he stood, and the first impression of slimness faded on closer inspection. He was big but trimly molded; a magnificent sweep of shoulder and depth of chest. Rangy he was, but compact, combining the strength of a bull with the lithe quickness of a panther. The slightest movement he made showed that steel-trap coordination that makes the super-fighter. Turlogh Dubh—Black Turlogh, once of the Clan na O'Brien. And black he was as to hair, and dark of complexion. From under heavy black brows gleamed eyes of a hot volcanic blue. And in his clean-shaven face there was something of the somberness of dark mountains, of the ocean at midnight. Like the fisherman, he was a part of this fierce land.

On his head he wore a plain vizorless helmet without crest or symbol. From neck to mid-thigh he was protected by a close-fitting shirt of black chain mail. The kilt he wore below his armor and which reached to his knees was of plain drab material. His legs were wrapped with hard leather that might turn a sword edge, and the shoes on his feet were worn with much traveling.

A broad belt encircled his lean waist, holding a long dirk in a leather sheath. On his left arm he carried a small round shield of hide-covered wood, hard as iron, braced and reinforced with steel, and having a short, heavy spike in the center. An ax hung from his right wrist, and it was to this feature that the fisherman's eyes wandered. The weapon with its three-foot handle and graceful lines looked slim and light when the fisherman mentally compared it to the great axes carried by the Norsemen. Yet scarcely three years had passed, as the fisherman knew, since such axes as these had shattered the northern hosts into red defeat and broken the pagan power forever.

There was individuality about the ax as about its owner. It was not like any other the fisherman had ever seen. Single-edged it was, with a short three-edged spike on the back and another on the top of the head. Like the wielder, it was heavier than it looked. With its slightly curved shaft and the graceful artistry of the blade, it looked like the weapon of an expert—swift, lethal, deadly, cobra-like. The head was of finest Irish workmanship, which meant, at that day, the finest in the world. The handle, cut from the head of a century-old oak, specially fire-hardened and braced with steel, was as unbreakable as an iron bar.

"Who are you?" asked the fisherman, with the bluntness of the west.

"Who are you to ask?" answered the other.

The fisherman's eyes roved to the single ornament the warrior wore—a heavy golden armlet on his left arm.

"Clean-shaven and close-cropped in the Norman fashion," he muttered. "And dark—you'd be Black Turlogh, the outlaw of Clan na O'Brien. You range far; I heard of you last in the Wicklow hills preying off the O'Reillys and the Oastmen alike."

"A man must eat, outcast or not," growled the Dalcassian.

The fisherman shrugged his shoulders. A masterless man—it was a hard road. In those days of clans, when a man's own kin cast him out he became a son of Ishmael with a vengeance. All men's hands were against him. The fisherman had heard of Turlogh Dubh—a strange, bitter man, a terrible warrior and a crafty strategist, but one whom sudden bursts of strange madness made a marked man even in that land and age of madmen.

"It's a bitter day," said the fisherman, apropos of nothing.

Turlogh stared somberly at his tangled beard and wild matted hair. "Have you a boat?"

The other nodded toward a small sheltered cove where lay snugly anchored a trim craft built with the skill of a hundred generations of men who had torn their livelihood from the stubborn sea.

"It scarce looks seaworthy," said Turlogh.

"Seaworthy? You who were born and bred on the western coast should know better. I've sailed her alone to Drumcliff Bay and back, and all the devils in the wind ripping at her."

"You can't take fish in such a sea."

"Do ye think it's only you chiefs that take sport in risking your hides? By the saints, I've sailed to Ballinskellings in a storm—and back too—just for the fun of the thing."

"Good enough," said Turlogh. "I'll take your boat."

"Ye'll take the devil! What kind of talk is this? If you want to leave Erin, go to Dublin and take the ship with your Dane friends."

A black scowl made Turlogh's face a mask of menace. "Men have died for less than that."

"Did you not intrigue with the Danes? And is that not why your clan drove you out to starve in the heather?"

"The jealousy of a cousin and the spite of a woman," growled Turlogh. "Lies—all lies. But enough. Have you seen a long serpent beating up from the south in the last few days?"

"Aye—three days ago we sighted a dragon-beaked galley before the scud. But she didn't put in—faith, the pirates get naught from the western fishers but hard blows."

"That would be Thorfel the Fair," muttered Turlogh, swaying his ax by its wrist-strap. "I knew it."

"There has been a ship-harrying in the south?"

"A band of reavers fell by night on the castle on Kilbaha. There was a sword-quenching—and the pirates took Moira, daughter of Murtagh, a chief of the Dalcassians."

"I've heard of her," muttered the fisherman. "There'll be a wetting of swords in the south—a red sea-plowing, eh, my black jewel?"

"Her brother Dermod lies helpless from a sword-cut in the foot. The lands of her clan are harried by the MacMurroughs in the east and the O'Connors from the north. Not many men can be spared from the defense of the tribe, even to seek for Moira—the clan is fighting for its life. All Erin is rocking under the Dalcassian throne since great Brian fell. Even so, Cormac O'Brien has taken ship to hunt down her ravishers—but he follows the trail of a wild goose, for it is thought the riders were Danes from Coningbeg. Well—we outcasts have ways of knowledge—it was Thorfel the Fair who holds the Isle of Slyne, that the Norse call Helni, in the Hebrides. There he has taken her—there I follow him. Lend me your boat."

"You are mad!" cried the fisherman sharply. "What are you saying. From Connacht to the Hebrides in an open boat? In this weather? I say you are mad."

"I will essay it," answered Turlogh absently. "Will you lend me your boat?"

"No."

"I might slay you and take it," said Turlogh.

"You might," returned the fisherman stolidly.

"You crawling swine," snarled the outlaw in swift passion, "a princess of Erin languishes in the grip of a red-bearded reaver of the north and you haggle like a Saxon."

"Man, I must live!" cried the fisherman as passionately. "Take my boat and I shall starve! Where can I get another like it? It is the cream of its kind!"

Turlogh reached for the armlet on his left arm. "I will pay you. Here is a torc that Brian Boru put on my arm with his own hand before Clontarf. Take it; it would buy a hundred boats. I have starved with it on my arm, but now the need is desperate."

But the fisherman shook his head, the strange illogic of the Gael burning in his eyes. "No! My hut is no place for a torc that King Brian's hands have touched. Keep it—and take the boat, in the name of the saints, if it means that much to you."

"You shall have it back when I return," promised Turlogh, "and mayhap a golden chain that now decks the bull neck of some northern reaver."

The day was sad and leaden. The wind moaned and the everlasting monotone of the sea was like the sorrow that is born in the heart of man. The fisherman stood on the rocks and watched the frail craft glide and twist serpent-like among the rocks until the blast of the open sea smote it and tossed it like a feather. The wind caught sail and the slim boat leaped and staggered, then righted herself and raced before the gale, dwindling until it was but a dancing speck in the eyes of the watcher. And then a flurry of snow hid it from his sight.

Turlogh realized something of the madness of his pilgrimage. But he was bred to hardships and peril. Cold and ice and driving sleet that would have frozen a weaker man, only spurred him to greater efforts. He was as hard and supple as a wolf. Among a race of men whose hardiness astounded even the toughest Norsemen, Turlogh Dubh stood out alone. At birth he had been tossed into a snow-drift to test his right to survive. His childhood and boyhood had been spent on the mountains, coasts and moors of the west. Until manhood he had never worn woven cloth upon his body; a wolf-skin had formed the apparel of this son of a Dalcassian chief. Before his outlawry he could out-tire a horse, running all day long beside it. He had never wearied at swimming. Now, since the intrigues of jealous clansmen had driven him into the wastelands and the life of the wolf, his ruggedness was such as cannot be conceived by a civilized man.

The snow ceased, the weather cleared, the wind held. Turlogh necessarily hugged the coastline, avoiding the reefs against which it seemed again and again he would be dashed. With tiller, sail and oar he worked tirelessly. Not one man out of a thousand of seafarers could have accomplished it, but Turlogh did. He needed no sleep; as he steered he ate from the rude provisions the fisherman had provided him. By the time he sighted Malin Head the weather had calmed wonderfully. There was still a heavy sea, but the gale had slackened to a sharp breeze that sent the little boat skipping along. Days and nights merged into each other; Turlogh drove eastward. Once he put into shore for fresh water and to snatch a few hours' sleep.

As he steered he thought of the fisherman's last words: "Why should you risk your life for a clan that's put a price on your head?"

Turlogh shrugged his shoulders. Blood was thicker than water. The mere fact that his people had booted him out to die like a hunted wolf on the moors did not alter the fact that they were his people. Little Moira, daughter of Murtagh na Kilbaha, had nothing to do with it. He remembered her—he had played with her when he was a boy and she a babe—he remembered the deep grayness of her eyes and the burnished sheen of her black hair, the fairness of her skin. Even as a child she had been remarkably beautiful—why, she was only a child now, for he, Turlogh, was young and he was many years her senior. Now she was speeding north to become the unwilling bride of a Norse reaver. Thorfel the Fair—the Handsome—Turlogh swore by gods that knew not the cross. A red mist waved across his eyes so that the rolling sea swam crimson all around him. An Irish girl a captive in a skalli of a Norse pirate—with a vicious wrench Turlogh turned his bows straight for the open sea. There was a tinge of madness in his eyes.

It is a long slant from Malin Head to Helni straight out across the foaming billows, as Turlogh took it. He was aiming for a small island that lay, with many other small islands, between Mull and the Hebrides. A modern seaman with charts and compass might have difficulty in finding it. Turlogh had neither. He sailed by instinct and through knowledge. He knew these seas as a man knows his house. He had sailed them as a raider and as an avenger, and once he had sailed them as a captive lashed to the deck of a Danish dragon ship. And he followed a red trail. Smoke drifting from headlands, floating pieces of wreckage, charred timbers showed that Thorfel was ravaging as he went. Turlogh growled in savage satisfaction; he was close behind the Viking, in spite of the long lead. For Thorfel was burning and pillaging the shores as he went, and Turlogh's course was like an arrow's.

He was still a long way from Helni when he sighted a small island slightly off his course. He knew it of old as one uninhabited, but there he could get fresh water. So he steered for it. The Isle of Swords it was called, no man knew why. And as he neared the beach he saw a sight which he rightly interpreted. Two boats were drawn up on the shelving shore. One was a crude affair, something like the one Turlogh had, but considerably larger. The other was a long, low craft—undeniably Viking. Both were deserted. Turlogh listened for the clash of arms, the cry of battle, but silence reigned. Fishers, he thought, from the Scotch isles; they had been sighted by some band of rovers on ship or on some other island, and had been pursued in the long rowboat. But it had been a longer chase than they had anticipated, he was sure; else they would not have started out in an open boat. But inflamed with the murder lust, the reavers would have followed their prey across a hundred miles of rough water, in an open boat, if necessary.

Turlogh drew inshore, tossed over the stone that served for anchor and leaped upon the beach, ax ready. Then up the shore a short distance he saw a strange red huddle of forms. A few swift strides brought him face to face with mystery. Fifteen red-bearded Danes lay in their own gore in a rough circle. Not one breathed. Within this circle, mingling with the bodies of their slayers, lay other men, such as Turlogh had never seen. Short of stature they were, and very dark; their staring dead eyes were the blackest Turlogh had ever seen. They were scantily armored, and their stiff hands still gripped broken swords and daggers. Here and there lay arrows that had shattered on the corselets of Danes, and Turlogh observed with surprize that many of them were tipped with flint.

"This was a grim fight," he muttered. "Aye, this was a rare sword-quenching. Who are these people? In all the isles I have never seen their like before. Seven—is that all? Where are their comrades who helped them slay these Danes?"

No tracks led away from the bloody spot. Turlogh's brow darkened.

"These were all—seven against fifteen—yet the slayers died with the slain. What manner of men are these who slay twice their number of Vikings? They are small men—their armor is mean. Yet—"

Another thought struck him. Why did not the strangers scatter and flee, hide themselves in the woods? He believed he knew the answer. There, at the very center of the silent circle, lay a strange thing. A statue it was, of some dark substance and it was in the form of a man. Some five feet long—or high—it was, carved in a semblance of life that made Turlogh start. Half over it lay the corpse of an ancient man, hacked almost beyond human semblance. One lean arm was locked about the figure; the other was outstretched, the hand gripping a flint dagger which was sheathed to the hilt in the breast of a Dane. Turlogh noted the fearful wounds that disfigured all the dark men. They had been hard to kill—they had fought until literally hacked to pieces, and dying, they had dealt death to their slayers. So much Turlogh's eyes showed him. In the dead faces of the dark strangers was a terrible desperation. He noted how their dead hands were still locked in the beards of their foes. One lay beneath the body of a huge Dane, and on this Dane Turlogh could see no wound; until he looked closer and saw the dark man's teeth were sunk, beast-like, into the bull throat of the other.

He bent and dragged the figure from among the bodies. The ancient's arm was locked about it, and he was forced to tear it away with all his strength. It was as if, even in death, the old one clung to his treasure; for Turlogh felt that it was for this image that the small dark men had died. They might have scattered and eluded their foes, but that would have meant giving up their image. They chose to die beside it. Turlogh shook his head; his hatred of the Norse, a heritage of wrongs and outrages, was a burning, living thing, almost an obsession, that at times drove him to the point of insanity. There was, in his fierce heart, no room for mercy; the sight of these Danes, lying dead at his feet, filled him with savage satisfaction. Yet he sensed here, in these silent dead men, a passion stronger than his. Here was some driving impulse deeper than his hate. Aye—and older. These little men seemed very ancient to him, not old as individuals are old, but old as a race is old. Even their corpses exuded an intangible aura of the primeval. And the image—

The Gael bent and grasped it, to lift it. He expected to encounter great weight and was astonished. It was no heavier than if it had been made of light wood. He tapped it, and the sound was solid. At first he thought it was of iron; then he decided it was of stone, but such stone as he had never seen; and he felt that no such stone was to be found in the British Isles or anywhere in the world that he knew. For like the little dead men, it looked old. It was smooth and free from corrosion, as if carved yesterday, but for all that, it was a symbol of antiquity, Turlogh knew. It was the figure of a man who much resembled the small dark men who lay about it. But it differed subtly. Turlogh felt somehow that this was the image of a man who had lived long ago, for surely the unknown sculptor had had a living model. And he had contrived to bring a touch of life into his work. There was the sweep of the shoulders, the depth of the chest, the powerfully molded arms; the strength of the features was evident. The firm jaw, the regular nose, the high forehead, all indicated a powerful intellect, a high courage, an inflexible will. Surely, thought Turlogh, this man was a king—or a god. Yet he wore no crown; his only garment was a sort of loincloth, wrought so cunningly that every wrinkle and fold was carved as in reality.

"This was their god," mused Turlogh, looking about him. "They fled before the Danes—but died for their god at last. Who are these people? Whence come they? Whither were they bound?"

He stood, leaning on his ax, and a strange tide rose in his soul. A sense of mighty abysses of time and space opened before him; of the strange, endless tides of mankind that drift forever; of the waves of humanity that wax and wane with the waxing and waning of the sea-tides. Life was a door opening upon two black, unknown worlds—and how many races of men with their hopes and fears, their loves and their hates, had passed through that door—on their pilgrimage from the dark to the dark? Turlogh sighed. Deep in his soul stirred the mystic sadness of the Gael.

"You were a king once, Dark Man," he said to the silent image. "Mayhap you were a god and reigned over all the world. Your people passed—as mine are passing. Surely you were a king of the Flint People, the race whom my Celtic ancestors destroyed. Well—we have had our day, and we, too, are passing. These Danes who lie at your feet—they are the conquerors now. They must have their day—but they too will pass. But you shall go with me, Dark Man, king, god, or devil though you be. Aye, for it is in my mind that you will bring me luck, and luck is what I shall need when I sight Helni, Dark Man."

Turlogh bound the image securely in the bows. Again he set out for his sea-plowing. Now the skies grew gray and the snow fell in driving lances that stung and cut. The waves were gray-grained with ice and the winds bellowed and beat on the open boat. But Turlogh feared not. And his boat rode as it had never ridden before. Through the roaring gale and the driving snow it sped, and to the mind of the Dalcassian it seemed that the Dark Man lent him aid. Surely he had been lost a hundred times without supernatural assistance. With all his skill at boat-handling he wrought, and it seemed to him that there was an unseen hand on the tiller, and at the oar; that more than human skill aided him when he trimmed his sail.

And when all the world was a driving white veil in which even the Gael's sense of direction was lost, it seemed to him that he was steering in compliance with a silent voice that spoke in the dim reaches of his consciousness. Nor was he surprized when, at last, when the snow had ceased and the clouds had rolled away beneath a cold silvery moon, he saw land loom up ahead and recognized it as the isle of Helni. More, he knew that just around a point of land was the bay where Thorfel's dragon ship was moored when not ranging the seas, and a hundred yards back from the bay lay Thorfel's skalli. He grinned fiercely. All the skill in the world could not have brought him to this exact spot—it was pure luck—no, it was more than luck. Here was the best possible place for him to make an approach—within half a mile of his foe's hold, yet hidden from sight of any watchers by this jutting promontory. He glanced at the Dark Man in the bows—brooding, inscrutable as the sphinx. A strange feeling stole over the Gael—that all this was his work; that he, Turlogh, was only a pawn in the game. What was this fetish? What grim secret did those carven eyes hold? Why did the dark little men fight so terribly for him?

Turlogh ran his boat inshore, into a small creek. A few yards up this he anchored and stepped out onshore. A last glance at the brooding Dark Man in the bows, and he turned and went hurriedly up the slope of the promontory, keeping to cover as much as possible. At the top of the slope he gazed down on the other side. Less than half a mile away Thorfel's dragon ship lay at anchor. And there lay Thorfel's skalli, also the long low building of rough-hewn log emitting the gleams that betokened the roaring fires within. Shouts of wassail came clearly to the listener through the sharp still air. He ground his teeth. Wassail! Aye, they were celebrating the ruin and destruction they had committed—the homes left in smoking embers—the slain men—the ravished girls. They were lords of the world, these Vikings—all the southland lay helpless beneath their swords. The southland folk lived only to furnish them sport—and slaves—Turlogh shuddered violently and shook as if in a chill. The blood-sickness was on him like a physical pain, but he fought back the mists of passion that clouded his brain. He was here, not to fight but to steal away the girl they had stolen.

He took careful note of the ground, like a general going over the plan of his campaign. He noted where the trees grew thick close behind the skalli; that the smaller houses, the storehouses and servants' huts were between the main building and the bay. A huge fire was blazing down by the shore and a few carles were roaring and drinking about it, but the fierce cold had driven most of them into the drinking-hall of the main building.

Turlogh crept down the thickly wooded slope, entering the forest which swept about in a wide curve away from the shore. He kept to the fringe of its shadows, approaching the skalli in a rather indirect route, but afraid to strike out boldly in the open lest he be seen by the watchers that Thorfel surely had out. Gods, if he only had the warriors of Clare at his back as he had of old! Then there would be no skulking like a wolf among the trees! His hand locked like iron on his ax-shaft as he visualized the scene—the charge, the shouting, the blood-letting, the play of the Dalcassian axes—he sighed. He was a lone outcast; never again would he lead the swordsmen of his clan to battle.

He dropped suddenly in the snow behind a low shrub and lay still. Men were approaching from the same direction in which he had come—men who grumbled loudly and walked heavily. They came into sight—two of them, huge Norse warriors, their silver-scaled armor flashing in the moonlight. They were carrying something between them with difficulty and to Turlogh's amazement he saw it was the Dark Man. His consternation at the realization that they had found his boat was gulfed in a greater astonishment. These men were giants; their arms bulged with iron muscles. Yet they were staggering under what seemed a stupendous weight. In their hands the Dark Man seemed to weigh hundreds of pounds; yet Turlogh had lifted it as lightly as a feather! He almost swore in his amazement. Surely these men were drunk. One of them spoke, and Turlogh's short neck hairs bristled at the sound of the guttural accents, as a dog will bristle at the sight of a foe.

"Let it down; Thor's death, the thing weighs a ton. Let's rest."

The other grunted a reply, and they began to ease the image to the earth. Then one of them lost his hold on it; his hand slipped and the Dark Man crashed heavily into the snow. The first speaker howled.

"You clumsy fool, you dropped it on my foot! Curse you, my ankle's broken!"

"It twisted out of my hand!" cried the other. "The thing's alive, I tell you!"

"Then I'll slay it," snarled the lame Viking, and drawing his sword, he struck savagely at the prostrate figure. Fire flashed as the blade shivered into a hundred pieces, and the other Norseman howled as a flying sliver of steel gashed his cheek.

"The devil's in it!" shouted the other, throwing his hilt away. "I've not even scratched it! Here, take hold—let's get it into the ale-hall and let Thorfel deal with it."

"Let it lie," growled the second man, wiping the blood from his face. "I'm bleeding like a butchered hog. Let's go back and tell Thorfel that there's no ship stealing on the island. That's what he sent us to the point to see."

"What of the boat where we found this?" snapped the other. "Some Scotch fisher driven out of his course by the storm and hiding like a rat in the woods now, I guess. Here, bear a hand; idol or devil, we'll carry this to Thorfel."

Grunting with the effort, they lifted the image once more and went on slowly, one groaning and cursing as he limped along, the other shaking his head from time to time as the blood got into his eyes.

Turlogh rose stealthily and watched them. A touch of chilliness traveled up and down his spine. Either of these men was as strong as he, yet it was taxing their powers to the utmost to carry what he had handled easily. He shook his head and took up his way again.

At last he reached a point in the woods nearest the skalli. Now was the crucial test. Somehow he must reach that building and hide himself, unperceived. Clouds were gathering. He waited until one obscured the moon and in the gloom that followed, ran swiftly and silently across the snow, crouching. A shadow out of the shadows he seemed. The shouts and songs from within the long building were deafening. Now he was close to its side, flattening himself against the rough-hewn logs. Vigilance was most certainly relaxed now—yet what foe should Thorfel expect, when he was friends with all northern reavers, and none else could be expected to fare forth on a night such as this had been?

A shadow among the shadows, Turlogh stole about the house. He noted a side door and slid cautiously to it. Then he drew back close against the wall. Someone within was fumbling at the latch. Then a door was flung open and a big warrior lurched out, slamming the door to behind him. Then he saw Turlogh. His bearded lips parted, but in that instant the Gael's hands shot to his throat and locked there like a wolf-trap. The threatened yell died in a gasp. One hand flew to Turlogh's wrist, the other drew a dagger and stabbed upward. But already the man was senseless; the dagger rattled feebly against the outlaw's corselet and dropped into the snow. The Norseman sagged in his slayer's grasp, his throat literally crushed by that iron grip. Turlogh flung him contemptuously into the snow and spat on his dead face before he turned again to the door.

The latch had not fastened within. The door sagged a trifle. Turlogh peered in and saw an empty room, piled with ale barrels. He entered noiselessly, shutting the door but not latching it. He thought of hiding his victim's body, but he did not know how he could do it. He must trust to luck that no one saw it in the deep snow where it lay. He crossed the room and found it led into another parallel with the outer wall. This was also a storeroom, and was empty. From this a doorway, without a door but furnished with a curtain of skins, let into the main hall, as Turlogh could tell from the sounds on the other side. He peered out cautiously.

He was looking into the drinking-hall—the great hall which served as a banquet, council, and living-hall of the master of the skalli. This hall, with its smoke-blackened rafters, great roaring fireplaces, and heavily laden boards, was a scene of terrific revelry tonight. Huge warriors with golden beards and savage eyes sat or lounged on the rude benches, strode about the hall or sprawled full length on the floor. They drank mightily from foaming horns and leathern jacks, and gorged themselves on great pieces of rye bread and huge chunks of meat they cut with their daggers from whole roasted joints. It was a scene of strange incongruity, for in contrast with these barbaric men and their rough songs and shouts, the walls were hung with rare spoils that betokened civilized workmanship. Fine tapestries that Norman women had worked; richly chased weapons that princes of France and Spain had wielded; armor and silken garments from Byzantium and the Orient—for the dragon ships ranged far. With these were placed the spoils of the hunt, to show the Viking's mastery of beasts as well as men.

The modern man can scarcely conceive of Turlogh O'Brien's feeling toward these men. To him they were devils—ogres who dwelt in the north only to descend on the peaceful people of the south. All the world was their prey to pick and choose, to take and spare as it pleased their barbaric whims. His brain throbbed and burned as he gazed. As only a Gael can hate, he hated them—their magnificent arrogance, their pride and their power, their contempt for all other races, their stern, forbidding eyes—above all else he hated the eyes that looked scorn and menace on the world. The Gaels were cruel but they had strange moments of sentiment and kindness. There was no sentiment in the Norse make-up.

The sight of this revelry was like a slap in Black Turlogh's face, and only one thing was needed to make his madness complete. This was furnished. At the head of the board sat Thorfel the Fair, young, handsome, arrogant, flushed with wine and pride. He was handsome, was young Thorfel. In build he much resembled Turlogh himself, except that he was larger in every way, but there the resemblance ceased. As Turlogh was exceptionally dark among a dark people, Thorfel was exceptionally blond among a people essentially fair. His hair and mustache were like fine-spun gold and his light gray eyes flashed scintillant lights. By his side—Turlogh's nails bit into his palms, Moira of the O'Briens seemed greatly out of place among these huge blond men and strapping yellow-haired women. She was small, almost frail, and her hair was black with glossy bronze tints. But her skin was fair as theirs, with a delicate rose tint their most beautiful women could not boast. Her full lips were white now with fear and she shrank from the clamor and uproar. Turlogh saw her tremble as Thorfel insolently put his arm about her. The hall waved redly before Turlogh's eyes and he fought doggedly for control.

"Thorfel's brother, Osric, to his right," he muttered to himself; "on the other side Tostig, the Dane, who can cleave an ox in half with that great sword of his—they say. And there is Halfgar, and Sweyn, and Oswick, and Athelstane, the Saxon—the one man of a pack of sea-wolves. And name of the devil—what is this? A priest?"

A priest it was, sitting white and still in the rout, silently counting his beads, while his eyes wandered pitying toward the slender Irish girl at the head of the board. Then Turlogh saw something else. On a smaller table to one side, a table of mahogany whose rich scrollwork showed that it was loot from the southland, stood the Dark Man. The two crippled Norsemen had brought it to the hall, after all. The sight of it brought a strange shock to Turlogh and cooled his seething brain. Only five feet tall? It seemed much larger now, somehow. It loomed above the revelry, as a god that broods on deep dark matters beyond the ken of the human insects who howl at his feet. As always when looking at the Dark Man, Turlogh felt as if a door had suddenly opened on outer space and the wind that blows among the stars. Waiting—waiting—for whom? Perhaps the carven eyes of the Dark Man looked through the skalli walls, across the snowy waste, and over the promontory. Perhaps those sightless eyes saw the five boats that even now slid silently with muffled oars, through the calm dark waters. But of this Turlogh Dubh knew nothing; nothing of the boats or their silent rowers; small, dark men with inscrutable eyes.

Thorfel's voice cut through the din: "Ho, friends!" They fell silent and turned as the young sea-king rose to his feet. "Tonight," he thundered, "I am taking a bride!"

A thunder of applause shook the noisy rafters. Turlogh cursed with sick fury.

Thorfel caught up the girl with rough gentleness and set her on the board.

"Is she not a fit bride for a Viking?" he shouted. "True, she's a bit shy, but that's only natural."

"All Irish are cowards!" shouted Oswick.

"As proved by Clontarf and the scar on your jaw!" rumbled Athelstane, which gentle thrust made Oswick wince and brought a roar of rough mirth from the throng.

"'Ware her temper, Thorfel," called a bold-eyed young Juno who sat with the warriors. "Irish girls have claws like cats."

Thorfel laughed with the confidence of a man used to mastery. "I'll teach her her lessons with a stout birch switch. But enough. It grows late. Priest, marry us."

"Daughter," said the priest unsteadily, rising, "these pagan men have brought me here by violence to perform Christian nuptials in an ungodly house. Do you marry this man willingly?"

"No! No! Oh God, No!" Moira screamed with a wild despair that brought the sweat to Turlogh's forehead. "Oh most holy master, save me from this fate! They tore me from my home—struck down my brother that would have saved me! This man bore me off as if I were a chattel—a soulless beast!"

"Be silent!" thundered Thorfel, slapping her across the mouth, lightly but with enough force to bring a trickle of blood from her delicate lips. "By Thor, you grow independent. I am determined to have a wife, and all the squeals of a puling little wench will not stop me. Why, you graceless hussy, am I not wedding you in the Christian manner, simply because of your foolish superstitions? Take care that I do not dispense with the nuptials, and take you as slave, not wife!"

"Daughter," quavered the priest, afraid, not for himself, but for her, "bethink you! This man offers you more than many a man would offer. It is at least an honorable married state."

"Aye," rumbled Athelstane, "marry him like a good wench and make the best of it. There's more than one southland woman on the cross benches of the north."

What can I do? The question tore through Turlogh's brain. There was but one thing to do—wait—until the ceremony was over and Thorfel had retired with his bride. Then steal her away as best he could. After that—but he dared not look ahead. He had done and would do his best. What he did, he of necessity did alone; a masterless man had no friends, even among masterless men. There was no way to reach Moira to tell her of his presence. She must go through with the wedding without even the slim hope of deliverance that knowledge of his presence might have lent. Instinctively, his eyes flashed to the Dark Man standing somber and aloof from the rout. At his feet the old quarreled with the new—the pagan with the Christian—and Turlogh even in that moment felt that the old and new were alike young to the Dark Man.

Did the carven ears of the Dark Man hear strange prows grating on the beach, the stroke of a stealthy knife in the night, the gurgle that marks the severed throat? Those in the skalli heard only their own noise and those who revelled by the fire outside sang on, unaware of the silent coils of death closing about them.

"Enough!" shouted Thorfel. "Count your beads and mutter your mummery, priest! Come here, wench, and marry!" He jerked the girl off the board and plumped her down on her feet before him. She tore loose from him with flaming eyes. All the hot Gaelic blood was roused in her.

"You yellow-haired swine!" she cried. "Do you think that a princess of Clare, with Brian Boru's blood in her veins, would sit at the cross bench of a barbarian and bear the tow-headed cubs of a northern thief? No—I'll never marry you!"

"Then I'll take you as a slave!" he roared, snatching at her wrist.

"Nor that way either, swine!" she exclaimed, her fear forgotten in fierce triumph. With the speed of light she snatched a dagger from his girdle, and before he could seize her she drove the keen blade under her heart. The priest cried out as though he had received the wound, and springing forward, caught her in his arms as she fell.

"The curse of Almighty God on you, Thorfel!" he cried, with a voice that rang like a clarion, as he bore her to a couch nearby.

Thorfel stood nonplussed. Silence reigned for an instant, and in that instant Turlogh O'Brien went mad.

"Lamh Laidir Abu!" the war cry of the O'Briens ripped through the stillness like the scream of a wounded panther, and as men whirled toward the shriek, the frenzied Gael came through the doorway like the blast of a wind from Hell. He was in the grip of the Celtic black fury beside which the berserk rage of the Viking pales. Eyes glaring and a tinge of froth on his writhing lips, he crashed among the men who sprawled, off guard, in his path. Those terrible eyes were fixed on Thorfel at the other end of the hall, but as Turlogh rushed he smote to right and left. His charge was the rush of a whirlwind that left a litter of dead and dying men in his wake.

Benches crashed to the floor, men yelled, ale flooded from upset casks. Swift as was the Celt's attack, two men blocked his way with drawn swords before he could reach Thorfel—Halfgar and Oswick. The scarred-faced Viking went down with a cleft skull before he could lift his weapon, and Turlogh, catching Halfgar's blade on his shield, struck again like lightning and the clean ax sheared through hauberk, ribs and spine.

The hall was in a terrific uproar. Men were seizing weapons and pressing forward from all sides, and in the midst the lone Gael raged silently and terribly. Like a wounded tiger was Turlogh Dubh in his madness. His eerie movement was a blur of speed, an explosion of dynamic force. Scarce had Halfgar fallen when the Gael leaped across his crumpling form at Thorfel, who had drawn his sword and stood as if bewildered. But a rush of carles swept between them. Swords rose and fell and the Dalcassian ax flashed among them like the play of summer lightning. On either hand and from before and behind a warrior drove at him. From one side Osric rushed, swinging a two-handed sword; from the other a house-carle drove in with a spear. Turlogh stooped beneath the swing of the sword and struck a double blow, forehand and back. Thorfel's brother dropped, hewed through the knee, and the carle died on his feet as the back-lash return drove the ax's back-spike through his skull. Turlogh straightened, dashing his shield into the face of the swordsman who rushed him from the front. The spike in the center of the shield made a ghastly ruin of his features; then even as the Gael wheeled cat-like to guard his rear, he felt the shadow of Death loom over him. From the corner of his eye he saw the Dane Tostig swinging his great two-handed sword, and jammed against the table, off balance, he knew that even his superhuman quickness could not save him. Then the whistling sword struck the Dark Man on the table and with a clash like thunder, shivered to a thousand blue sparks. Tostig staggered, dazedly, still holding the useless hilt, and Turlogh thrust as with a sword; the upper spike of his ax struck the Dane over the eye and crashed through to the brain.

And even at that instant, the air was filled with a strange singing and men howled. A huge carle, ax still lifted, pitched forward clumsily against the Gael, who split his skull before he saw that a flint-pointed arrow transfixed his throat. The hall seemed full of glancing beams of light that hummed like bees and carried quick death in their humming. Turlogh risked his life for a glance toward the great doorway at the other end of the hall. Through it was pouring a strange horde. Small, dark men they were, with beady black eyes and immobile faces. They were scantily armored, but they bore swords, spears, and bows. Now at close range they drove their long black arrows point-blank and the carles went down in windrows.

Now a red wave of combat swept the skalli hall, a storm of strife that shattered tables, smashed the benches, tore the hangings and trophies from the walls, and stained the floors with a red lake. There had been less of the black strangers than Vikings, but in the surprize of the attack, the first flight of arrows had evened the odds, and now at hand-grips the strange warriors showed themselves in no way inferior to their huge foes. Dazed with surprize and the ale they had drunk, with no time to arm themselves fully, the Norsemen yet fought back with all the reckless ferocity of their race. But the primitive fury of the attackers matched their own valor, and at the head of the hall, where a white-faced priest shielded a dying girl, Black Turlogh tore and ripped with a frenzy that made valor and fury alike futile.

And over all towered the Dark Man. To Turlogh's shifting glances, caught between the flash of sword and ax, it seemed that the image had grown— expanded—heightened; that it loomed giant-like over the battle; that its head rose into smoke-filled rafters of the great hall—that it brooded like a dark cloud of death over these insects who cut each other's throats at its feet. Turlogh sensed in the lightning sword-play and the slaughter that this was the proper element for the Dark Man. Violence and fury were exuded by him. The raw scent of fresh-spilled blood was good to his nostrils and these yellow-haired corpses that rattled at his feet were as sacrifices to him.

The storm of battle rocked the mighty hall. The skalli became a shambles where men slipped in pools of blood, and slipping, died. Heads spun grinning from slumping shoulders. Barbed spears tore the heart, still beating, from the gory breast. Brains splashed and clotted the madly driving axes. Daggers lunged upward, ripping bellies and spilling entrails upon the floor. The clash and clangor of steel rose deafeningly. No quarter was asked or given. A wounded Norseman had dragged down one of the dark men, and doggedly strangled him regardless of the dagger his victim plunged again and again into his body.

One of the dark men seized a child who ran howling from an inner room, and dashed its brains out against the wall. Another gripped a Norse woman by her golden hair and hurling her to her knees, cut her throat, while she spat in his face. One listening for cries of fear or pleas of mercy would have heard none; men, women or children, they died slashing and clawing, their last gasp a sob of fury, or a snarl of quenchless hatred.

And about the table where stood the Dark Man, immovable as a mountain, washed the red waves of slaughter. Norsemen and tribesmen died at his feet. How many red infernos of slaughter and madness have your strange carved eyes gazed upon, Dark Man?

Shoulder to shoulder Sweyn and Thorfel fought. The Saxon Athelstane, his golden beard a-bristle with the battle-joy, had placed his back against the wall and a man fell at each sweep of his two-handed ax. Now Turlogh came in like a wave, avoiding, with a lithe twist of his upper body, the first ponderous stroke. Now the superiority of the light Irish ax was proved, for before the Saxon could shift his heavy weapon, the Dalcassian ax lit out like a striking cobra and Athelstane reeled as the edge bit through the corselet into the ribs beneath. Another stroke and he crumpled, blood gushing from his temple.

Now none barred Turlogh's way to Thorfel except Sweyn, and even as the Gael leaped like a panther toward the slashing pair, one was ahead of him. The chief of the Dark Men glided like a shadow under the slash of Sweyn's sword, and his own short blade thrust upward under the mail. Thorfel faced Turlogh alone. Thorfel was no coward; he even laughed with pure battle-joy as he thrust, but there was no mirth in Black Turlogh's face, only a frantic rage that writhed his lips and made his eyes coals of blue fire.

In the first swirl of steel Thorfel's sword broke. The young sea-king leaped like a tiger at his foe, thrusting with the shards of the blade. Turlogh laughed fiercely as the jagged remnant gashed his cheek, and at the same instant he cut Thorfel's left foot from under him. The Norseman fell with a heavy crash, then struggled to his knees, clawing for his dagger. His eyes were clouded.

"Make an end, curse you!" he snarled.

Turlogh laughed. "Where is your power and your glory now?" he taunted. "You who would have for unwilling wife an Irish princess—you—"

Suddenly his hate strangled him, and with a howl like a maddened panther he swung his ax in a whistling arc that cleft the Norseman from shoulder to breastbone. Another stroke severed the head, and with the grisly trophy in his hand he approached the couch where lay Moira O'Brien. The priest had lifted her head and held a goblet of wine to her pale lips. Her cloudy gray eyes rested with slight recognition of Turlogh—but it seemed at last she knew him and she tried to smile.

"Moira, blood of my heart," said the outlaw heavily, "you die in a strange land. But the birds in the Culland hills will weep for you, and the heather will sigh in vain for the tread of your little feet. But you shall not be forgotten; axes shall drip for you and for you shall galleys crash and walled cities go up in flames. And that your ghost go not unassuaged into the realms of Tir-na-n-Oge, behold this token of vengeance!"

And he held forth the dripping head of Thorfel.

"In God's name, my son," said the priest, his voice husky with horror, "have done—have done. Will you do your ghastly deeds in the very presence of—see, she is dead. May God in His infinite justice have mercy on her soul, for though she took her own life, yet she died as she lived, in innocence and purity."

Turlogh dropped his ax-head to the floor and his head was bowed. All the fire of his madness had left him and there remained only a dark sadness, a deep sense of futility and weariness. Over all the hall there was no sound. No groans of the wounded were raised, for the knives of the little dark men had been at work, and save their own, there were no wounded. Turlogh sensed that the survivors had gathered about the statue on the table and now stood looking at him with inscrutable eyes. The priest mumbled over the body of the girl, telling his beads. Flames ate at the farther wall of the building, but none heeded it. Then from among the dead on the floor a huge form heaved up unsteadily. Athelstane the Saxon, overlooked by the killers, leaned against the wall and stared about dazedly. Blood flowed from a wound in his ribs and another in his scalp where Turlogh's ax had struck glancingly.

The Gael walked over to him. "I have no hatred for you, Saxon," said he, heavily, "but blood calls for blood and you must die."

Athelstane looked at him without an answer. His large gray eyes were serious, but without fear. He too was a barbarian—more pagan than Christian; he too realized the rights of the blood-feud. But as Turlogh raised his ax, the priest sprang between, his thin hands outstretched, his eyes haggard.

"Have done! In God's name I command you! Almighty Powers, has not enough blood been shed this fearful night? In the name of the Most High, I claim this man."

Turlogh dropped his ax. "He is yours; not for your oath or your curse, not for your creed but for that you too are a man and did your best for Moira."

A touch on his arm made Turlogh turn. The chief of the strangers stood regarding him with inscrutable eyes.

"Who are you?" asked the Gael idly. He did not care; he felt only weariness.

"I am Brogar, chief of the Picts, Friend of the Dark Man."

"Why do you call me that?" asked Turlogh.

"He rode in the bows of your boat and guided you to Helni through wind and snow. He saved your life when he broke the great sword of the Dane."

Turlogh glanced at the brooding Dark One. It seemed there must be human or superhuman intelligence behind those strange stone eyes. Was it chance alone that caused Tostig's sword to strike the image as he swung it in a death blow?

"What is this thing?" asked the Gael.

"It is the only God we have left," answered the other somberly. "It is the image of our greatest king, Bran Mak Morn, he who gathered the broken lines of the Pictish tribes into a single mighty nation, he who drove forth the Norseman and Briton and shattered the legions of Rome, centuries ago. A wizard made this statue while the great Morni yet lived and reigned, and when he died in the last great battle, his spirit entered into it. It is our god.

"Ages ago we ruled. Before the Dane, before the Gael, before the Briton, before the Roman, we reigned in the western isles. Our stone circles rose to the sun. We worked in flint and hides and were happy. Then came the Celts and drove us into the wilderness. They held the southland. But we throve in the north and were strong. Rome broke the Britons and came against us. But there rose among us Bran Mak Morn, of the blood of Brule the Spear-slayer, the friend of King Kull of Valusia who reigned thousands of years ago before Atlantis sank. Bran became king of all Caledon. He broke the iron ranks of Rome and sent the legions cowering south behind their Wall.

"Bran Mak Morn fell in battle; the nation fell apart. Civil wars rocked it. The Gaels came and reared the kingdom of Dalriadia above the ruins of the Cruithni. When the Scot Kenneth McAlpine broke the kingdom of Galloway, the last remnant of the Pictish empire faded like snow on the mountains. Like wolves we live now among the scattered islands, among the crags of the highlands and the dim hills of Galloway. We are a fading people. We pass. But the Dark Man remains—the Dark One, the great king, Bran Mak Morn, whose ghost dwells forever in the stone likeness of his living self."

As in a dream Turlogh saw an ancient Pict who looked much like the one in whose dead arms he had found the Dark Man, lift the image from the table. The old man's arms were thin as withered branches and his skin clung to his skull like a mummy's, but he handled with ease the image that two strong Vikings had had trouble in carrying.

As if reading his thoughts, Brogar spoke softly: "Only a friend may with safety touch the Dark One. We knew you to be a friend, for he rode in your boat and did you no harm."

"How know you this?"

"The Old One," pointing to the white-bearded ancient, "Gonar, high priest of the Dark One—the ghost of Bran comes to him in dreams. It was Grok, the lesser priest and his people who stole the image and took to sea in a long boat. In dreams Gonar followed; aye, as he slept he sent his spirit with the ghost of the Morni, and he saw the pursuit by the Danes, the battle and slaughter on the Isle of Swords. He saw you come and find the Dark One, and he saw that the ghost of the great king was pleased with you. Woe to the foes of Mak Morn! But good luck shall fare the friends of him."

Turlogh came to himself as from a trance. The heat of the burning hall was in his face and the flickering flames lit and shadowed the carven face of the Dark Man as his worshippers bore him from the building, lending it a strange life. Was it, in truth, that the spirit of a long-dead king lived in that cold stone? Bran Mak Morn loved his people with a savage love; he hated their foes with a terrible hate. Was it possible to breathe into inanimate blind stone a pulsating love and hate that should outlast the centuries?

Turlogh lifted the still, slight form of the dead girl and bore her out of the flaming hall. Five long open boats lay at anchor, and scattered about the embers of the fires the carles had lit, lay the reddened corpses of the revelers who had died silently.

"How stole ye upon these undiscovered?" asked Turlogh. "And whence came you in those open boats?"

"The stealth of the panther is theirs who live by stealth," answered the Pict. "And these were drunken. We followed the path of the Dark One and we came hither from the Isle of Altar, near the Scottish mainland, from whence Grok stole the Dark Man."

Turlogh knew no island of that name but he did realize the courage of these men in daring the seas in boats such as these. He thought of his own boat and requested Brogar to send some of his men for it. The Pict did so. While he waited for them to bring it around the point, he watched the priest bandaging the wounds of the survivors. Silent, immobile, they spoke no word either of complaint or thanks.

The fisherman's boat came scudding around the point just as the first hint of sunrise reddened the waters. The Picts were getting into their boats, lifting in the dead and wounded. Turlogh stepped into his boat and gently eased his pitiful burden down.

"She shall sleep in her own land," he said somberly. "She shall not lie in this cold foreign isle. Brogar, whither go you?"

"We take the Dark One back to his isle and his altar," said the Pict. "Through the mouth of his people he thanks you. The tie of blood is between us, Gael, and mayhap we shall come to you again in your need, as Bran Mak Morn, great king of Pictdom, shall come again to his people some day in the days to come."

"And you, good Jerome? You will come with me?"

The priest shook his head and pointed to Athelstane. The wounded Saxon reposed on a rude couch made of skins piled on the snow.

"I stay here to attend this man. He is sorely wounded."

Turlogh looked about. The walls of the skalli had crashed into a mass of glowing embers. Brogar's men had set fire to the storehouses and the long galley, and the smoke and flame vied luridly with the growing morning light.

"You will freeze or starve. Come with me."

"I will find sustenance for us both. Persuade me not, my son."

"He is a pagan and a reaver."

"No matter. He is a human—a living creature. I will not leave him to die."

"So be it."

Turlogh prepared to cast off. The boats of the Picts were already rounding the point. The rhythmic clacks of their oar-locks came clearly to him. They looked not back, bending stolidly to their work.

He glanced at the stiff corpses about the beach, at the charred embers of the skalli and the glowing timbers of the galley. In the glare the priest seemed unearthly in his thinness and whiteness, like a saint from some old illuminated manuscript. In his worn pallid face was a more than human sadness, a greater than human weariness.

"Look!" he cried suddenly, pointing seaward. "The ocean is of blood! See how it swims red in the rising sun! Oh my people, my people, the blood you have spilt in anger turns the very seas to scarlet! How can you win through?"

"I came in the snow and sleet," said Turlogh, not understanding at first. "I go as I came."

The priest shook his head. "It is more than a mortal sea. Your hands are red with blood and you follow a red sea-path, yet the fault is not wholly with you. Almighty God, when will the reign of blood cease?"

Turlogh shook his head. "Not so long as the race lasts."

The morning wind caught and filled his sail. Into the west he raced like a shadow fleeing the dawn. And so passed Turlogh Dubh O'Brien from the sight of the priest Jerome, who stood watching, shading his weary brow with his thin hand, until the boat was a tiny speck far out on the tossing wastes of the blue ocean.